Annihilation: Expedition Unknown

Rob Hardy, BSC mixes digital cameras and lenses to help frame a biologist’s unsettling, otherworldly experience in Alex Garland’s surreal sci-fi thriller.

Unit photography by Peter Mountain, courtesy of Paramount Pictures Lighting diagrams courtesy of Andy Lowe

Something is amiss on the Gulf Coast. A strange force has taken root, surrounding the swampland with a penetrable, multi-colored dome the government has dubbed “the Shimmer.” A military troop sent in to investigate has returned only one of its members (Oscar Isaac), and he is gravely and mysteriously ill. His wife, biologist Lena (Natalie Portman), joins the next expedition, determined to find out what happened to him. The teamis led by a psychologist (Jennifer Jason Leigh), and includes an anthropologist (Gina Rodriguez), surveyor (Tessa Thompson) and linguist (Tuva Novotny).

“There are elements of ‘everything’s weird in Area X, so we’re going to do these things to make it look weird.’”

What they find inside the so-called Area X is hardly reassuring. Plants and animals have mutated in ways beyond scientific explanation — and as the team gets as far as the previous group had ventured, the situation becomes more troubling. Unearthly creatures appear and attack, and some patrol members start behaving strangely. Lena must track down their main adversary and determine how it functions to stop it from wreaking devastating consequences.

Annihilation is based on the first novel in Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach trilogy — so named for the government agency investigating Area X. The movie marks the follow-up for the team of writer-director Alex Garland and director of photography Rob Hardy, BSC, who previously collaborated on the acclaimed AI thriller Ex Machina (AC May ’15).

During three months of preproduction, one other movie provided inspiration: Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 Soviet sci-fi fantasy Stalker, in which a guide brings two men through a surreal wasteland known as the Zone in search of a room purported to fulfill desires. That film balances a sepia-toned black-and-white “normal” world with a moody, verdant Zone shot in color. “But for us, when it comes to imagery, anything goes, and often it was about generating our own source material,” Hardy says from his home in London, on a day off from shooting M:I 6 – Mission Impossible with director Christopher McQuarrie.

Hardy was living in Los Angeles during prep for Annihilation, and visited San Marino’s Huntington Botanical Gardens with a still camera. “I was taking photographs of strange plants from an architectural point of view, looking for inorganic patterns and shapes,” he explains. “I was trying to find odd images that nature provides.”

The production scouted the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge in northwest Florida, which inspired Area X in VanderMeer’s novel, but the thickness of the vegetation presented a challenge. The U.K.-based production decided instead to stay close to home, shooting the forest exteriors in Windsor Great Park, the historic hunting grounds for the British royal family near Windsor Castle. Interiors were shot about 13 miles away at Pinewood Studios outside London.

Hardy snapped a photo study of Windsor Great Park, focusing on the lush vegetation in dark, natural light and atmospheric fog. Production designer Mark Digby and set decorator Michelle Day then dressed up the park with plant life indigenous to the southern U.S. — with an emphasis on the exotic — and the filmmakers had their credible setting.

As with Stalker, there are two worlds at play: the normal world and the familiar yet otherworldly Area X. Garland and Hardy weren’t aiming for a hard divide between the looks for each, so much as a visual arc tracking Lena’s emotional state as she moves in and out of the Shimmer. Hardy looked to put this across by alternating primarily between Sony F65 CineAlta and Red Weapon Dragon 6K cameras.

“Natalie’s character’s journey was the springboard for the look,” the cinematographer explains. “There are elements of ‘everything’s weird in Area X, so we’re going to do these things to make it look weird,’ but also when she returns from Area X, she brings back psychological elements of that place with her.”

Shooting with the F65 as they did on Ex Machina, Hardy and Garland achieved a naturalistic look for the establishing scenes, recording uncompressed 4K Sony Raw files to 256GB and 512GB Sony SRMemory Cards. Hardy notes that they coupled the camera with the “very clean glass” of Panavision Primo Anamorphic Prime lenses. “The Sony camera has such a well-rounded look,” he offers. “It’s so beautiful and has a very filmic way of dealing with things. The sensor really ‘understands’ the subtleties and strange values of the glass. I knew I would have a very soft feel with the F65.”

As the Shimmer and its frightening implications are introduced, Hardy subtly shifted to the Red camera fitted with Panavision G Series Anamorphic Primes — a rig that became his workhorse for footage inside Area X. “The Red had a snappy feel, bringing the jungle environment right out into the forefront,” he says. “It didn’t pull any punches, whereas the Sony camera was more subtle. And when we got to Area X, we couldn’t pull any punches — that’s when the Red came into its own.

Though the crew had tested one, an 8K Red unit wouldn’t be production-ready in time for the shoot. Nonetheless, Hardy says, “The 6K gave us everything we needed. The sensor seemed to ‘aggravate’ the outer edges of the G Series lenses exactly how we wanted.”

The production shot Redcode Raw files at 3:1 compression — the least amount the camera allows — and recorded to 256GB and 512GB Red Mini-Mags. A Standard OLPF (optical low-pass filter) was used throughout.

Hardy pressed Panavision Ultra Panatar anamorphic lenses into service for heightened visual moments, such as a scene in which Lena wakes up and sees abstracted colors in the air through an opening in her tent. When she returns to the normal world yet remains affected by what she’s seen, the cinematographer stuck with the Red but went back to the Primos.

“It’s very complicated,” he reflects with a laugh. “First AC Jennie Paddon was pulling her hair out with the whole system and saying, ‘This is crazy!’ But in a subtle way it works.” Adding yet another variable, Hardy handheld a Sony PMW-F55 CineAlta — fitted with a 50mm G Series — for a scene in which a distraught Lena, believing her missing husband will never return, looks for a fresh start by determinedly repainting her room.

Garland tells AC via e-mail that Hardy took the lead on all such matters. “The look, as defined by the camera choice and the differences between sensors, all came from Rob,” he writes. “We discuss these things, but the decision is made by him. That would also apply to the choice of lens sets and the framing on the day. After rehearsing with the actors, the first thing I do is turn to Rob and say, ‘How do you want to shoot this?’

“There may be a specific move or angle I’m after, but Rob always has something he knows he wants, which is usually the defining shot of the scene,” the director continues. “We almost invariably agree, and on the rare occasions we don’t, I’ll defer to him. That’s actually the principle of how the whole film is made. I’m not interested in the director as boss. The film is the boss, and it’s made by a collective.”

Hardy generally kept the lenses within the 30mm-50mm lens range, and for the most part shot at T2.8, though sometimes at T4, as he says some of the lenses resolve better at the narrower aperture. He used some diffusion filters — Black Pro-Mist, primarily 1⁄8 density and occasionally 1⁄4 — as well as NDs.

Digital-imaging technician Jay Patel explains that since they shot with the Red camera about 70 percent of the time, “it made sense to work with RedLogFilm as our starting point for color grading dailies. We built an IDT [input device transform] to convert Sony’s S-Log3 to look like RedLogFilm’s color space, and from there we created a show LUT. With the IDT in place for the Sony camera, we needed to create only one LUT for both our camera formats, and the dailies pipeline was a straightforward linear workflow.”

Digital colorist Asa Shoul at London post shop Molinare, who was involved during preproduction, adds, “We gave the LUT to Pinewood, which processed the dailies. It was slightly desaturated and not too contrasty. Rob likes a soft look and we tried hard not to crush detail.”

The filmmakers framed for the 2.39:1 aspect ratio. “There was no question for us,” Hardy explains. “It felt like the widescreen format worked well for this environment and the story we wanted to tell.” Footage was evaluated on set on Sony PVMA250 OLED monitors.

The 10-week shoot spanned spring through July 2016. Hardy was stationed on A camera, while veteran operator Vince McGahon handled B camera and Steadicam. Hardy estimates 90 percent of the shots were set up for one camera. “Alex and I favor a single camera, as it tends to give a much more focused aesthetic to the overall end result,” the cinematographer says. “But we used two cameras for certain sequences, such as some of the action.” McGahon’s Steadicam work was generally employed for footage in Area X, when the camera moved with the patrol. For the Southern Reach facility, however, Garland wanted what Hardy characterizes as the “more stoic” movement of dolly tracking.

For a sequence in which Lena confronts an alien foe by a lighthouse — which Hardy describes as more of a dance than a conventional battle — the filmmakers wanted a more “foreign” kind of movement, which they achieved by mounting a Red Weapon camera fitted with a G Series lens on a Stabileye miniature stabilized head. Key grip Sam Phillips held the rig while Hardy remotely operated with hand wheels, an audio link, and his eyes on a monitor. “With the Stabileye, there’s a kind of second-hand communication going on between the operator and the action,” Hardy notes. “You’re not as close to it as you would be with handheld, but you’re closer than you would be with somebody else operating Steadicam. It gave us a very strange effect that sits somewhere between intimacy and detachment, which was perfect for the scene. The stabilized mechanics created a very odd feel.”

Even amid the LED revolution, the cinematographer remained true to his long-standing philosophy of using tungsten lights nearly exclusively. “Before working with a gaffer who’s new to me, I make it clear I’m all about tungsten light,” he says. “I always get smirks and, ‘Sure, okay Rob,’ and then they realize I’m serious and we end up having to carry heavy tungsten lights into the middle of forests. But tungsten provides a certain flavor and texture I want, and I think it pays off.”

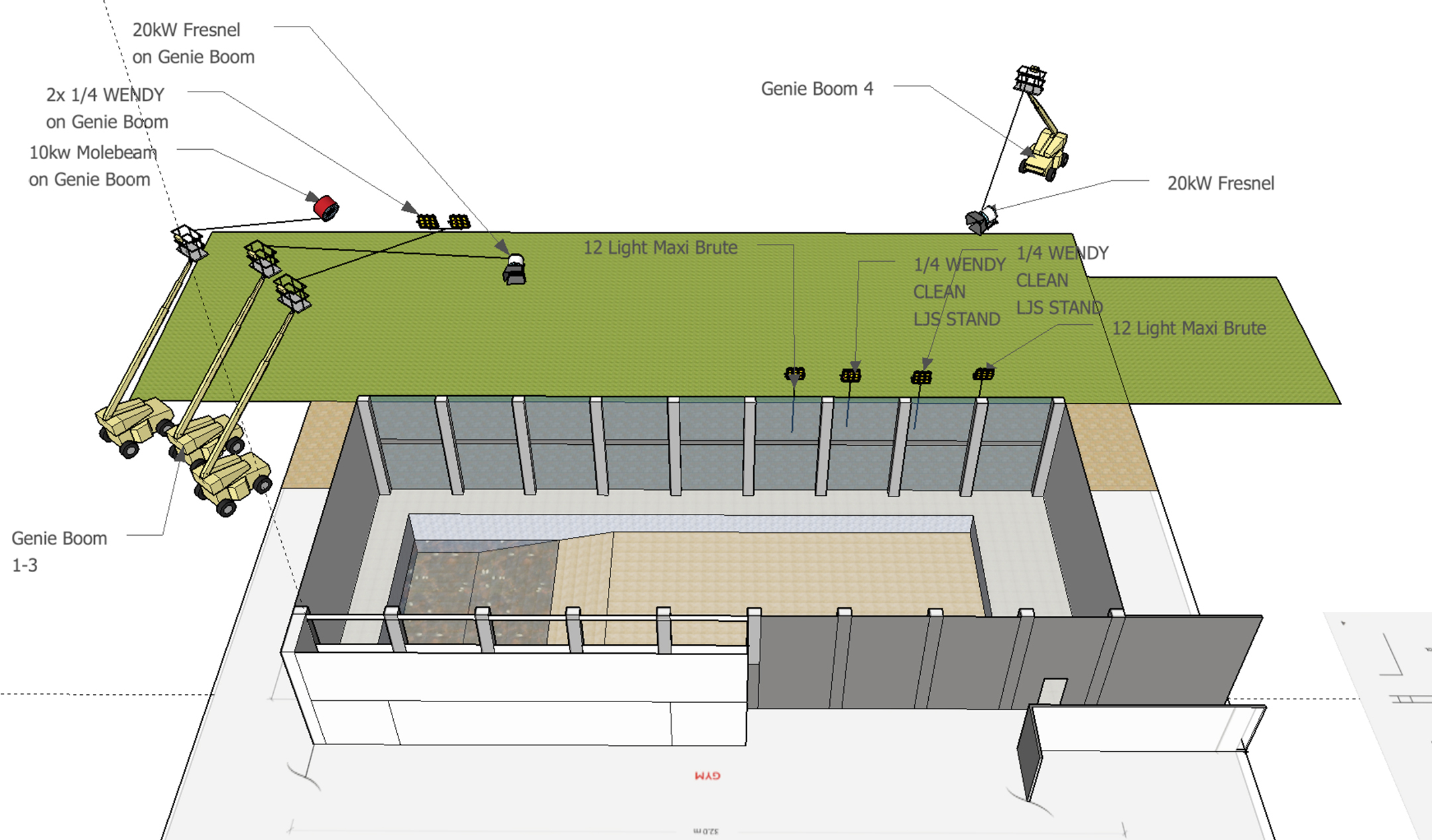

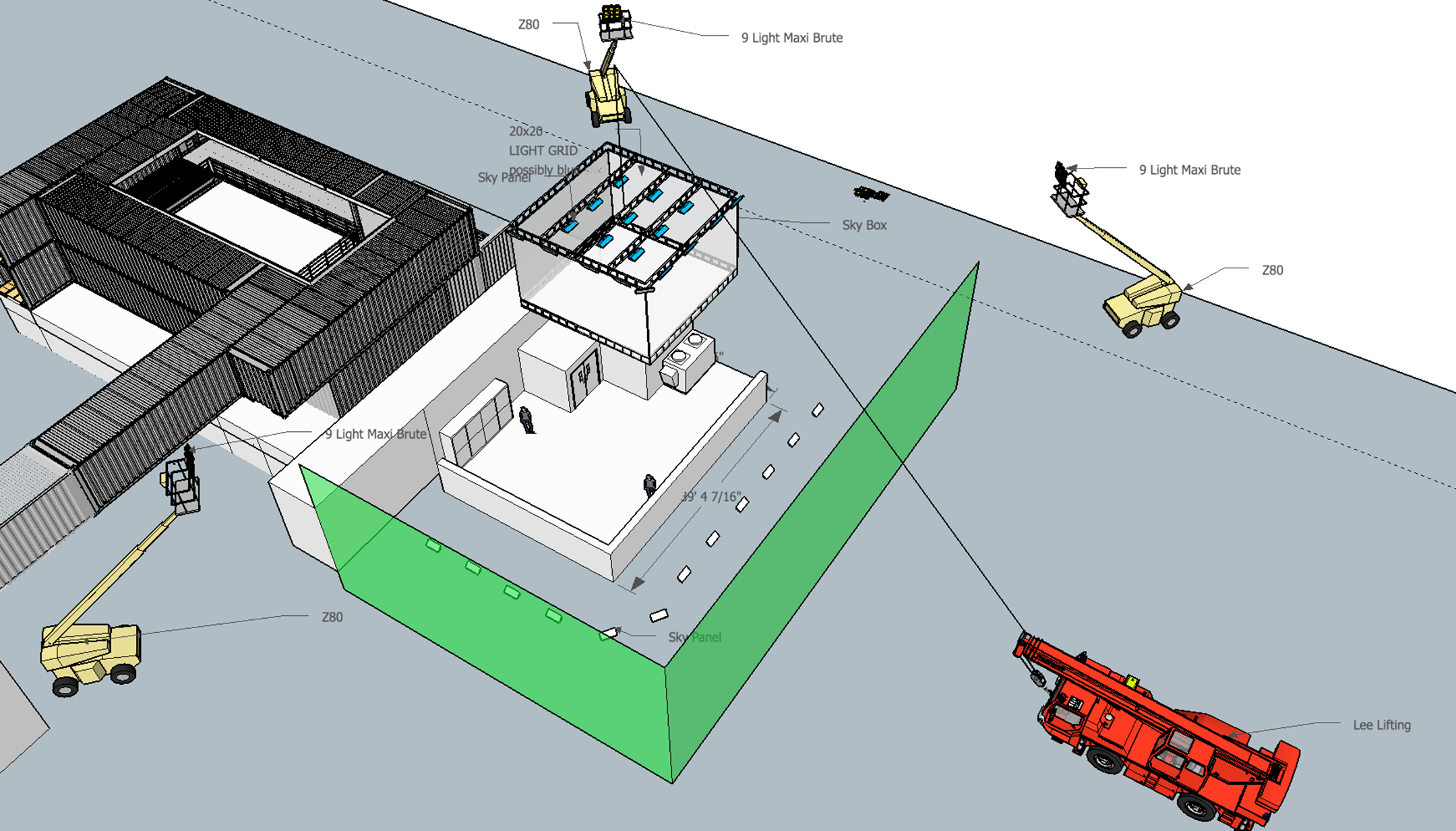

An early discussion revolved around the nature of the Shimmer and how light would behave inside it. The filmmakers decided to emphasize the refraction of the sun’s rays passing through the Shimmer’s flowing, translucent, rainbow surface. Prominent and unusual flares became the prime way of conveying that. The crew rigged artificial sources in Great Windsor Park, including a 24K Fresnel positioned away from the action, sometimes on a hill or mounted to an Avenger Long John Silver Stand or Genie boom lift. “We found with one source in the right place, several hundred feet away through the trees, we would occasionally catch lens flares or hotspots that helped sell the idea that there was sun around,” explains gaffer Andy Lowe.

A priority was to make those in-camera flares appear strange and unnatural. During prep at Panavision London, Hardy shot about six hours of flare tests on the F65 in front of black, projecting colored light into every lens he could find. Lowe recalls using various lights, including Source Fours; small flashlights; and a Rosco X24 X-Effects projector, which creates a rippling lighting effect via two spinning, colored gobos. “We would shine that into the lens at different angles to create various funky flares,” the gaffer says. They then blew up the flares they had shot, selected desired portions for specific moments within the Shimmer, and composited them into the footage to enhance the in-camera flares captured in the park.

“Except for the CG creatures, we physically generated the core ingredients of every visual effect,” Hardy says. “All the visual layers are generated in a very analog and natural way. The effect is something that feels real even though it’s trippy. We didn’t want to be out-and-out weird. We wanted everything to be embedded in reality.”

The cinematographer’s overall lighting approach in Area X was essentially independent of actor movement. “The actors were free to move, as most of the lighting was either integral to the sets or ‘off set,’” he says. “We did not differentiate between darker and lighter parts of the room; the actors used the shadow as well as the light. I did not want to restrict their movement and did not want it to feel preconceived by having them land in lit areas, as that feels fake to me. It’s about the space and the environment. The characters enter into that environment and the light behaves the way it behaves and we don’t change it. For me, it’s never about lighting specific people — it’s about lighting environments.”

The characters in these scenes are surrounded by points of light in the background and around the edges, as if, as Shoul suggests, “they were being oppressed or overwhelmed by the new environment, while enlightenment was just out of their reach.”

The sun effect around the actors was often enhanced by a line of four to six Quarter Wendy and Dino lights, which were placed low to the ground for sequences of the troop marching through the forest or paddling on a lake. “We would use those when there was an opportunity to kick in light from the side, when the actors are traveling in tracking shots or towards camera,” Lowe says. “That was easiest when we were shooting on one angle. If we wanted to pan, we would have to use additional lights further away.”

To make it seem that the colors from the Shimmer wall were permeating the air, the crew projected colored light from the Rosco X24 through atmosphere in the forest, and used their tungsten light sources with color gels. Hardy notes, “We didn’t want shafts of light, but rather we would sometimes project into the lens — and with very slow crane, dolly and Steadicam moves we would pass through these colors in such a subtle way that you felt them rather than saw them.”

One particular Area X night scene, which bears homage to traditional horror, required a far simpler setup. The troop sets up camp in an abandoned house, when one member goes rogue and ties up the others. The art department deliberately used the same set as Lena’s home, re-dressing it in an odd way, which only adds to her anxiety. As there is no electricity, the group illuminates the house by setting down their square flashlights on small tripods. This lights up the room — in which they’re later trapped — as well as the hallway outside, with the shadow from the grill of a flashlight cast on a yellow-green wall. Just as the characters fear, the light attracts a roaming bear-like creature, which inevitably enters the house and creeps up on them while they’re immobilized.

Aiming for authenticity, the filmmakers “spent a couple of weeks researching which night-lights military and scientific expeditions would take to remote places, that would be battery-powered and could adapt to harsh environments,” Hardy says. “We ended up using practical kits that could be carried in a backpack, and I used them to light those scenes.”

Although LED flashlights are currently the norm, true to Hardy’s philosophy, the art department custom-built practical tungsten units inspired by the Gam Stik-Up luminaire. The bespoke lights were 100 watts each — and quite hot, Hardy admits — and controlled by inline dimmers built by practical electrician Dom Aronin. “We had a few of them set up in a corner and used them to backlight the characters in their chairs and make some nice flares,” Lowe recalls. “To see their faces a little better, we used Rifa-Lites with extra diffusion as fill, always motivated by the [flashlights].”

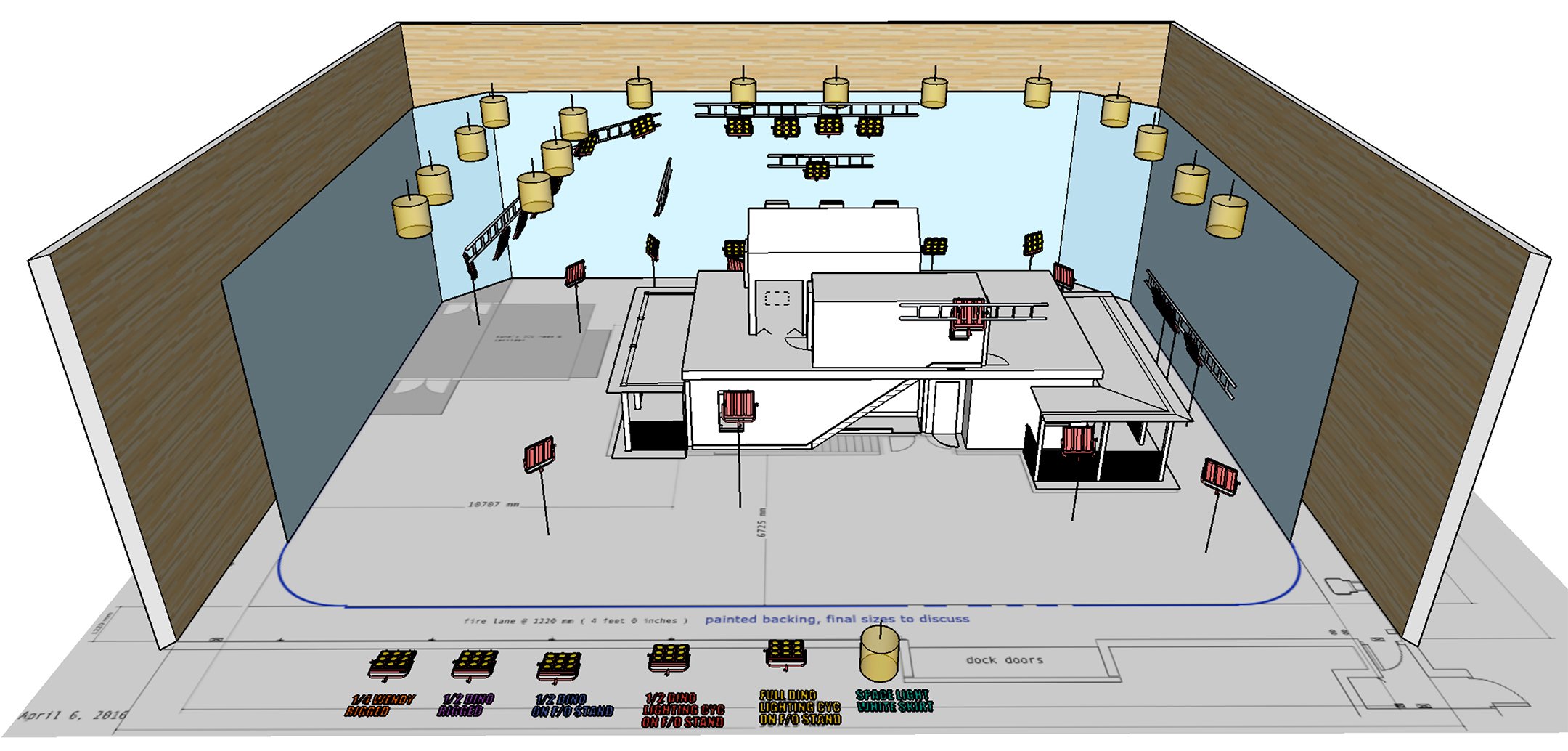

The exceptions to Hardy’s tungsten-only rule came during some night exteriors — including a scene at the closed RAF Upper Heyford air base northwest of London, which represented the previous Southern Reach facility, now abandoned since being engulfed by the Shimmer. Lena and the others take shelter in a guard tower and are terrified to see that a powerful creature has ripped through the surrounding fence. “I wanted to create that sense of night in a place where you don’t have light, and then add elements of the Shimmer and how that would affect moonlight,” Hardy says. “A soft box using the tungsten light I wanted would have been too big to lift into the air, and LED gave us the ability to naturally infuse those colored elements into the light.”

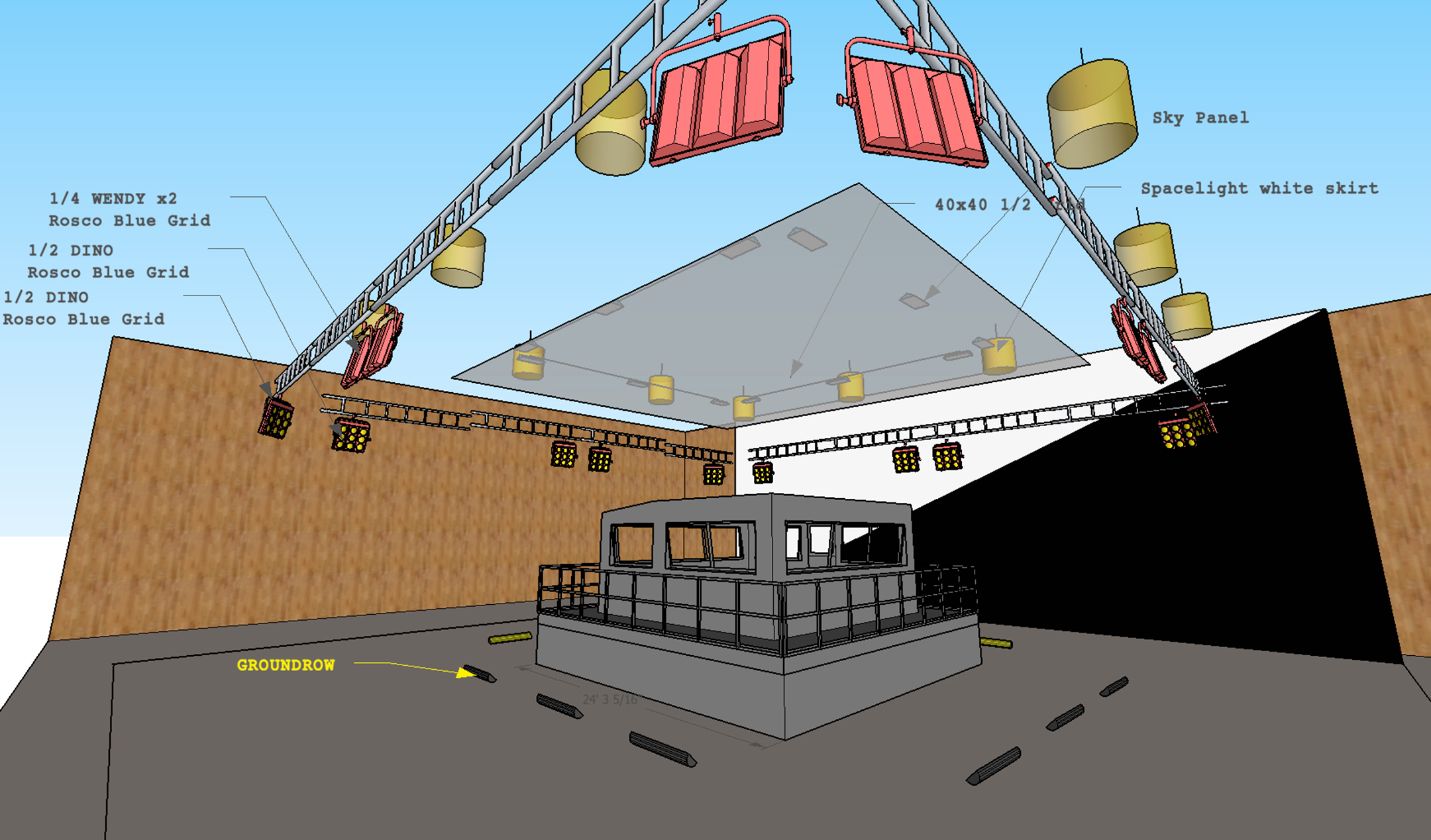

Therefore, the only sources for these scenes are the characters’ practical flashlights, and moonlight created by a 30'x30' soft box containing 40 Arri SkyPanels diffused with Full Grid, suspended on a crane. “We diffused not only the bottom but also the sides,” Lowe says. “We splayed the lights so they spilled out from the sides and didn’t feel like a top light. We tried to spread it as much as we could, so it had a softer falloff that traveled as far as possible.”

For visual-effects shots, Hardy had to be conscious of which lighting decisions they could safely lock in on the day. It was a dance among the filmmakers, visual-effects supervisor Andrew Whitehurst, and visual-effects providers that included Double Negative.

“It’s a faith-based approach,” Garland says. “We don’t know exactly where we’ll end up, but we have shared instincts or strong hunches, and we know the kind of latitudes that exist in post. But we also sometimes make mistakes. We shot a whole fight with an alligator where we forgot to get crucial clean [plates] of the alligator, because the alligator wasn’t ‘there.’ More than once, the visual-effects team had to create full CG shots to pick up our dropped ball.”

For a scene shot at Pinewood in which Lena descends a tunnel to confront an alien force in an underground lair, Hardy was faced with the question of how to light a subterranean space. As the movie gets increasingly surreal in its final act, the filmmakers felt they could take some liberties. “Alex’s big thing was that you sense the space, but he doesn’t want the audience to understand how big it is,” Hardy explains. “Where does it begin and where does it end?” The director of photography drew inspiration from H.P. Lovecraft’s 1930s novella At the Mountains of Madness, in which an ancient city under Antarctic ice is illuminated by a light that simply exists in and of itself.

Hardy had the art department construct a rough fiberglass model of the cloud-like alien, which would ultimately be replaced with a CG build. This gave Portman something to play against, and the light emanating from the floating, expanding being provided a motivating source. They stuffed four bare 1K tungsten bulbs in Octodome heads inside the fiberglass cast. Each was on its own dimmer, and with a simple chase they lit Portman’s face and some of the walls.

The alien also emits orbs of light that encircle and mesmerize Lena. These were created partly by lens flares from bulbs slightly larger than fairy lights, which were hung at varying heights on a chase. Fifty Sunstrip lights in three rows on an overhanging grid, also on a chase, added a sparkling effect.

The crew had a 20K MoleBeam pointing straight down the tunnel, and a couple of Quarter Wendy lights on either side kicking light on the tunnel sides. For shots looking directly up the tunnel, they would turn off the MoleBeam.

Though Hardy was unavailable for much of the grading after choosing to accept his M:I 6 mission, the cinematographer sat down with Shoul early in the finishing process — in Molinare’s largest theater — to set looks and do a couple of passes. Hardy also sent Shoul reference images of paintings, photographs of people, and various textures. As Shoul worked with Garland, the colorist was confident he knew what the cinematographer wanted.

Shoul notes, “I looked at artists Gerhard Richter and Maxfield Parrish for inspiration, as their landscapes are otherworldly — Richter’s being soft and blurred and Parrish’s heightened and graphic.” Although the Red camera had been chosen for the vibrancy of its greens in the forest, Shoul reports that they muted those greens in the end. “I added diffusion to most shots,” he adds, “which helped [with the incorporation of] visual effects, and gave a slightly dreamlike feel while adding a feeling of condensation to the air.”

The colorist says he used about 20 windows to grade the first close-up of the Shimmer wall to “focus the eye onto the right places for it to be as impressive as possible.” Shoul worked with 10-bit DPX files on a FilmLight Baselight system, with non-visual-effects files at 4K resolution and visual-effects shots at 2K.

“Alex’s vision is wholly original,” Hardy concludes. “It’s rare to see things like this. Certainly, there’s nothing else like it.”

Technical Specs

2.39:1

Cameras | Red Weapon Dragon 6K, Sony CineAlta F65, PMW-F55

Lenses | Panavision Primo Anamorphic Prime, G Series, Ultra Panatar

Hardy was invited to join the ASC in 2020. He and Garland later collaborated on the drama Civil War.