Civil War: Chronicling Chaos

Rob Hardy, ASC, BSC; director Alex Garland; and effects experts collaborate on a vision of warring American states presented through photojournalists’ eyes.

Unit photography by Murray Close. All images courtesy of A24.

In Civil War, a near-future America is torn between a radicalized U.S. president (played by Nick Offerman) and the “Western Forces” alliance of California and Texas. Director Alex Garland and cinematographer Rob Hardy, ASC, BSC — collaborating on their fifth feature — made combat photography integral to their vision, framing the drama through the lens of a renowned photojournalist covering the events.

“Our approach was always about what it must feel like to be present in a war zone,” says Hardy. “We wanted to create an authentic immersive experience.”

“I described the look of Civil War as ‘abrasive.’ We wanted to immerse the audience in this world in a very real way to make it all the more terrifying.”

— Rob Hardy, ASC, BSC

Interpretation and Immediacy

Seeking an interview with the rogue president, the photojournalist, Lee Smith (Kirsten Dunst), must make a harrowing journey from war-torn New York City to Washington, D.C., accompanied by her journalist colleague Joel (Wagner Moura), veteran correspondent Sammy (Stephen McKinley Henderson) and cub photographer Jessie Cullen (Cailee Spaeny).

“The first thing we focused on was what makes a war photograph,” Hardy says. “What happens in the moments before and after a picture is taken? Our intention was to do something that had real immediacy. I described the look of Civil War as ‘abrasive.’ We wanted to immerse the audience in this world in a very real way to make it all the more terrifying.”

Production was based in Atlanta, Ga., where military adviser Ray Mendoza, a former Navy SEAL, coordinated the film’s military presence with stunt coordinators Jeff Dashnaw and Wesley Scott. Garland notes, “Ray Mendoza and Jeff Dashnaw are incredibly experienced, creatively ambitious, clear-minded, can-do guys, [and] it’s hard to overstate their joint role. The sequences we devised needed a lot of hardware — tanks, helicopters and weaponry. Ray also brought in veterans to play [some of the] military characters; they influenced and elevated the film a great deal.”

Special-effects supervisor J.D. Schwalm and visual-effects supervisor David Simpson added to on-set action. “Rob and Alex like to shoot fast, and they like to find shots on the day,” says Simpson. “Alex told me he wanted military action to be as authentic as possible — he wanted to choreograph the military operation first and then stage his main cast around that. So, the action was carefully choreographed before we arrived on set, based on our lengthy roundtable conversations, but it needed to feel like it was happening in real time — hence, no storyboards or previs. During prep, I watched a lot of newsreel footage, and it was the unpredictable nature of that footage that inspired my approach to covering the action.”

An Immersive Mobile Environment

Hardy chose the Sony Venice for his main cameras, teaming them with Panavision H Series lenses. Sony a7S Mark IIIs served for interior and exterior multi-camera car rigs. However, the cinematographer estimates that approximately 70 percent of Civil War was shot using prototype DJI Ronin 4D/Zenmuse X9 camera rigs paired with specially modified Leitz M0.8 primes.

The filmmakers sought camera platforms that would best capture performances in the heat of battle and during the long traveling scenes in Joel’s press vehicle. “In the past, we’ve used things like Stabileye, Steadicam and handheld,” Hardy says. “What we were looking for was a device that could give us all that, but with a different way of moving. We wanted to find visual-capture mediums that would allow us to react in a way that would be elegant and give us the language we wanted, but at the same time put the audience right into the action. Our military advisers created authenticity, and we wanted our photography to immerse itself without being disruptive. That comes back to the idea of creating 360-degree environments, which Alex and I have done on all of our films.”

Hardy and gaffer Todd Heater, working with key grip Mackie Roberts, rigged the press vehicle to capture the actors’ performances on the fly. The cinematographer explains, “We had three vehicles: a Pod Vehicle, with a stunt driver on top; our camera car; and the ‘Coverage Car,’ which had up to 20 cameras attached. We had four actors in all three vehicles. We put two Venice cameras on the hood, covering the driver and passenger, and then rigged Sony a7S Mark IIIs around the car so we could capture reactions at any point. The Mark IIIs were useful simply because of their small footprint.

“For important storytelling points, we sometimes had driving shots with a camera out the window looking down onto an actor’s face looking out, and we’d see the reflection of landscape passing by,” he adds. “We had cross-shooting with front angles, and reverse angles from the back looking through the car to the front.”

For Pod Car scenes, where roof-mounted stunt drivers controlled steering, braking and acceleration — including a sequence in which Jessie switches seats with a passenger in a passing car — VFX artists erased the stunt drivers as well as reflections in windows and paintwork.

Most daylight driving scenes required minimal VFX assistance, with no lighting aside from diffusion or flagging of side windows. “It was quite a juggling act to rig the cameras in a way that kept them out of each other’s views,” says Simpson. “VFX occasionally cleaned up the odd cable that worked loose and snuck into the frame, but the majority of shots worked perfectly. What we saw outside a car window was real in every shot. We used no LED screens or greenscreens for driving backgrounds. It was 100 percent real cars on real roads.”

A Powerful Prototype

Garland and Hardy were thrilled with the combat-photography potential of the prototype Ronin 4D, which they tested during prep at Panavision U.K. The rig incorporates the Zenmuse X9, DJI’s flagship full-frame camera, and the company’s latest image-processing system, CineCore 3.0. Hardy explains, “If you imagine the body of a chicken, you hold the chicken from the sides, and its head sticks up vertically. As you walk along, the camera body moves but the head stays in the same place. The z-axis gives stability in that way, similar to a Steadicam, but the operator holds the camera, and they can move and control it from the handles. For action sequences, it was perfect. We could drop to the ground, lift up into an elegant move and then move quickly as we followed a character.” And with the unit’s Sport Mode feature, which, when toggled, causes the head to lock in place, “if we were pulling back with someone and then wanted to whip across, we could freeze the head, and suddenly it was a handheld camera.”

For the test, Garland, Hardy and camera operator/Ronin technician Chris DuMont took the rig for a drive in Garland’s car. The camera’s light weight — about 12 pounds — and Dual Operator mode sparked the team’s interest. “The genius part is that it could also go back to wheels operated remotely,” Hardy notes. “I would be operating on A camera, on comms, and we could instruct [another Ronin 4D operator] like a choreography in tandem, where I could take over for the more elegant camera motions. We could let the camera drop, go into ‘battle’ mode and move through fight sequences with instant elegance, instant handheld, and that was all there at the touch of a button. It was brilliant for that reason. We had six Ronin 4D prototypes.”

Convincing Combat

Battle action includes Lee’s first encounter with Jessie on the streets of Brooklyn, where a suicide bomber attacks a Western Forces gathering. The production staged the conflagration in downtown Atlanta, where Schwalm’s special-effects team initiated the pyrotechnic event. Framestore added the Manhattan skyline in the distance and enhanced the explosion, referencing a mix of documentary footage. Says Simpson, “We found news footage and ammunition tests, showed them to Alex, and he’d pick the most appropriate one. Then the effects team dug into those details, always trying to replicate [the] real footage.”

Jessie’s hero-worship of Lee causes Lee to recall horrors from her early career, including an instance when an African man was immolated within a car tire. Locations in Atlanta doubled for the west coast of Africa and the Middle East. SPFX and VFX collaborated on the immolation using a pyrotechnic element.

“One of the things that’s difficult with flames is determining exposure,” says Simpson. “How bright should the flames be? Unless you film a real flame, it’s very hard to get that right. We asked the prop department to provide a mannequin, and after they shot that scene, we filmed that burning. Then we created a combination of the mannequin and the plate.”

Stateside horrors unfurl as Jessie joins Lee on the road — highway wrecks, bombed-out malls and corpses dangling from nooses. “We wanted to present familiar locations with a civil-war aesthetic, whereas other towns that are unaffected had an uneasiness about them,” Hardy says.

Practical dressing included 10 derelict vehicles in the foreground of the movie’s most ambitious highway scene. Framestore added to the onscreen devastation. “We always kept degrees of real elements,” says Simpson. “Atlanta has a variety of derelict locations, so we found places that felt abandoned, dressed them for war and then added buildings smoldering in the deep background.”

Tracer fire suggests the threat of war in a nighttime campsite scene. Hardy’s crew lit the location with bare incandescent 1K bulbs and a distant condor supporting a Nine-light Maxi-Brute. “Tracers were an important storytelling device,” Simpson says. “Sometimes they’re single stabs of light, and sometimes they draw lines describing who’s shooting at whom. It was a needle-threading act to get that balance so you understood what was happening. [At the campsite] we see the tracers from afar, and Alex wanted them to arc and ricochet. At that distance, we [as the audience] can ‘safely’ observe their movement. Later, when we’re up close, the perspective is more chaotic and dangerous.”

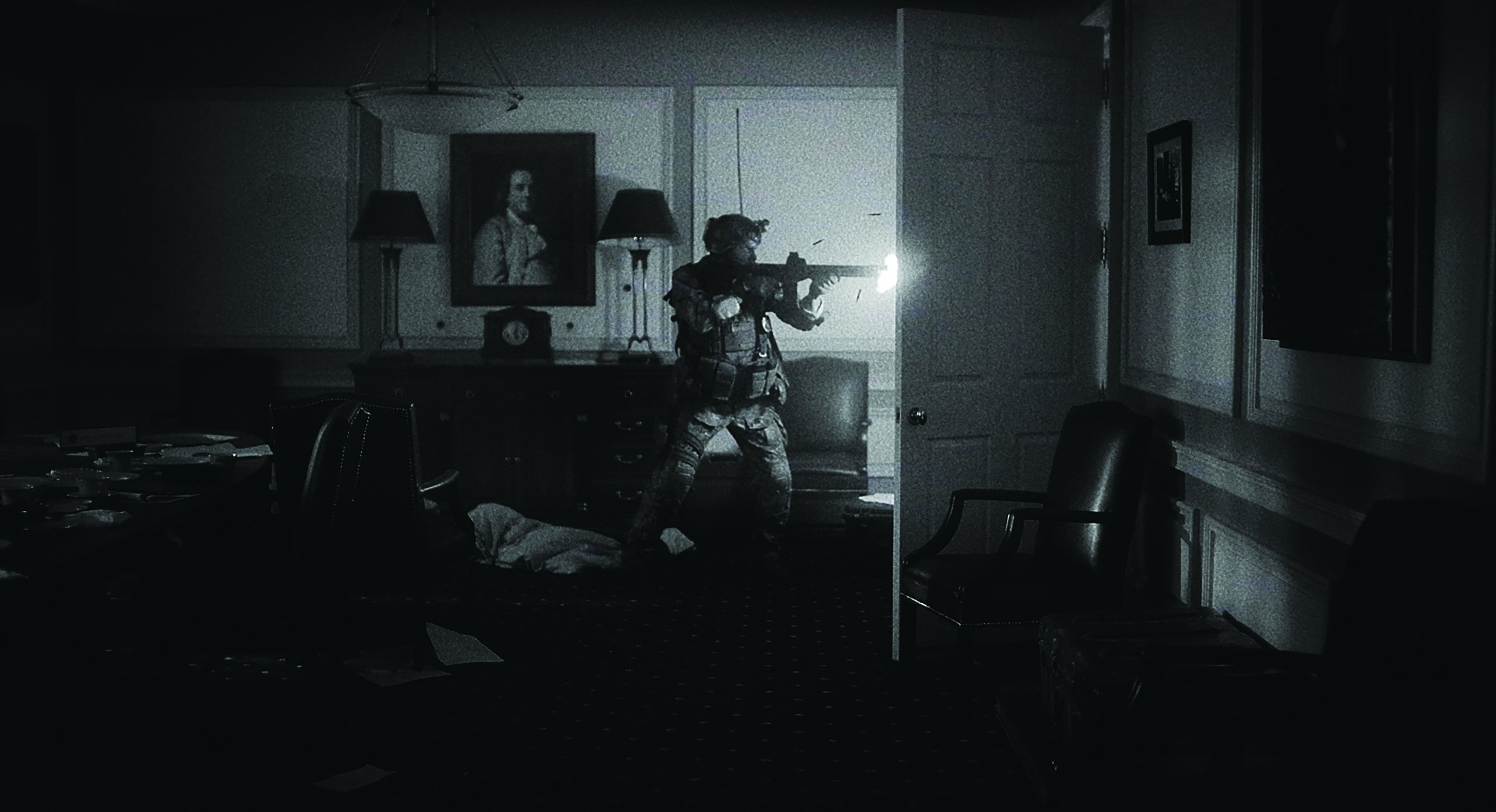

Lee’s group follows Western Forces into a firefight with opposing force in a bombed-out housing project, where soldiers advance with flashlights affixed to weapons. Bad weather plagued the two-day shoot at the location.

“We used Maxi-Brutes for fill in the exterior battle and had the interior lit from outside,” Heater says. “The problem was, when it came time to film the interior part of the scene, we had to shut down our generators due to lightning strikes. We were in danger of not being able to finish the shoot as the weather just got worse. So, the interior of that scene was filmed with Astera tubes, gun flashlights and battery-powered Kino Flo Freestyle 21s. It was dark, but it worked well for the scene.”

Hardy covered the sequence with multiple Ronin 4Ds, with operators in camouflage navigating tight quarters using Dual Operator mode. DuMont recalls, “One of the operators carried the camera into the stairwell, and Rob was there, operating on wheels and comms, framing the shot as they moved up through the stairs, the z-axis floating the camera through space. That gave us a nice synergy, moving in and reacting as Rob was finding the composition.”

The sequence involves editorial freeze frames that simulate Jessie’s black-and-white stills, emphasizing the photojournalist’s perspective. “A war photographer is surrounded by chaos, but when they raise their camera, they must find a stillness in the chaos to capture a picture,” DuMont observes. “The Ronin 4D can do that in Sport Mode — find the stillness that a photojournalist finds in that moment. When I clocked onto that about three weeks into shooting, I understood the decision-making behind that idea.”

Into the Fire

A later conflict leads Lee and company to flee for their lives by driving close to a forest fire. The sequence begins at dusk with an aerial view of the forest captured by aerial director of photography Dylan Goss and helicopter pilot Fred North. Framestore added elements of forest-fire photography and synthetic flames blended in 2D. Schwalm’s team staged the ground-level inferno. “I had written this imagery into several scripts previously and had never managed to pull it off,” Garland reveals. “But J.D. and I watched some images of cars driving through forest fires, with terrifying swirling clouds of embers, and he decided to fully take on the challenge. It’s the most stunning in-camera effects I’ve ever seen.”

Pyrotechnic devices extended 1/3 of a mile through a forest road, using metal “flame tree” structures spaced at intervals. A special-effects spark generator mounted behind a truck drove ahead of the follow car and Coverage Car, spewing airborne embers. Heater’s crew affixed Astera LED tubes to the Coverage Car roof rack to add ambience to car interiors. Framestore digitally tracked tree structures into practical flames and enhanced two shots to assist ember continuity in the otherwise in-camera sequence.

“One of our characters is passing away in this moment,” Hardy reveals, “so we wanted to add an element of surrealism. Every one of our movies has an element of surrealism, because what’s the point in life otherwise? It was a glorious thing.”

Lee and company pause at a large Western Forces encampment that’s preparing an attack on the U.S. Capitol. Framestore added to the sequence with one of the film’s few all-digital shots. Simpson explains, “There’s one shot on the ground where the Chinooks are picking the Humvee up off of the ground, and that became a full-CG shot because it was an idea that came later. But we looked at it in terms of filming it for real. We couldn’t safely get close to that helicopter, so we carefully replicated Rob’s lenses and chose our focal length and our camera body [to match].”

For the ground assault on Washington, the production used a parking-lot location in Stone Mountain, Ga., as a backlot. Sets of D.C. streets, backed by bluescreen, included a gun emplacement at the Lincoln Memorial and a heavily barricaded White House perimeter. Heater’s team emulated lighting on high alert using Maxi-Brutes, Arri SkyPanel 360s on condors and barrier-wall clusters of Fiilex Quad Color LEDs. “[The lights] needed to be flicker-free, rainproof and color-changing depending upon [what was being shot],” says Heater. “It was a long sequence, about eight nights, and we went for a mix of color temperatures as you see in real street lighting. Our locations team did a nighttime lighting study of D.C. so we could match it as closely as possible.”

To add environment extensions, Framestore created a 3D model of Washington based on scouts and photogrammetry studies. “The city model was insanely detailed,” says Simpson. “It was not just the outsides of the buildings, but the insides, too — with furniture, desks, computers, plants, whiteboards and elevators. They put so much into it because we knew we’d be looking up at buildings or flying over in a helicopter and would want to see all that detail inside.”

An Indelible Moment

Lee and her surviving colleagues ultimately accompany Western Forces into a fierce standoff with the president’s staff. Framestore generated the barricaded White House exterior as a digital model that was nested into wide shots. The production staged the White House approach and interiors at Tyler Perry Studios, where stunts and SPFX staged gunfire barrages using blanks. TPO VFX in London added bullet hits to help reduce the need for on-set reset times.

Amid the firefight, Lee is shot while protecting her protégé. Hardy captured the moment by simulating a 35mm freeze-frame using a Venice with a remote head on a dolly track.”

“I’m very much an operator/DP,” he says. “We worked with some great operators on this, but everything I do comes back to what the camera sees. I try to capture as much as possible myself, and the moment Lee gets hit was one of those singular images that Alex and I talked about in preproduction. We knew this shot had to cut through the chaos; the image almost has the weight of the entire movie behind it. How we captured it was designed specifically for that moment.”

Tech Specs

2.39:1

Cameras | Sony Venice, Red Weapon Dragon, DJI Ronin 4D-6K, Sony a7S III

Lenses | Panavision H Series, Leitz M0.8

Spotlight on Optics | “The Antithesis of a Modern Lens”

Hardy enjoyed a long unofficial prep for Civil War that began years before the official one commenced. He and Garland started discussing the project during post on the Hulu series Devs, and then the pandemic prompted them to switch gears and focus on the U.K.-based thriller Men (AC Oct. ’22). “We had all this time to think and to absorb the material,” Hardy says.

The London-based cinematographer made the most of this lead time by evaluating lenses at Panavision U.K. as often as he could. “Whenever I was there, I’d ask [technical marketing director] Charlie Todman to pull glass off the shelves,” he says. “We had time to refine [choices] and get things in place before we were ‘boots on the ground’ in Atlanta.”

After using Panavision’s H Series lenses on other projects, Hardy was keen to use them again. The spherical lenses “give character, but they’re small enough to be adaptable to any situation,” he says.

He especially wanted to secure a specific 75mm whose unique aberrations had dazzled him and Garland before. “While using the 75mm on a shot for Men, “we discovered an insane haloing effect,” Hardy continues. “It’s where Rory Kinnear appears as a very untrustworthy priest — he was walking down the aisle of a church, we did a tilt down, and this weird, inverted halo appeared around his head. We weren’t expecting that to happen, but the effect is due to the often beautiful aberrations in Panavision glass. It’s what makes them unique.”

On Civil War, Hardy used the lens for a bold composition featuring Lee and Jessie sharing a quiet moment in a boathouse, backlit by a lake reflecting shimmering highlights. “When we latched onto the boathouse location, we picked our angle very carefully, and we knew the 75mm would offer up its full glory,” the cinematographer says.

The favored lens “has spherical aberration and a very smooth edge roll-off that is the antithesis of a modern lens,” notes ASC associate Dan Sasaki of Panavision. “There is also a unique warmth about it that is directly related to the vintage glass types used and the coatings available during the era [1960s] when the glass was manufactured.”

Another mission at Panavision was finding lenses for the other camera rigs Hardy planned to use on Civil War — Sony’s a7S Mark III and DJI’s Ronin 4D — that would reasonably match the H Series. Research revealed the Leitz M0.8s as a compact, lightweight option suited to both camera platforms, “but I found the Leitz lenses to be too clean, so Dan Sasaki and his team [modified] them to match characteristics of the H Series,” Hardy says. “That gave us two sets of lenses we could combine beautifully and seamlessly.”

Re-creating some of the singular lens effects in Hardy’s images for digital composites was an ongoing challenge for the visual-effects team — but a pleasure, too, according to Simpson.

“One of the things I loved about Rob’s lens choices was a style of optical occlusion — at the edge of frame, the bokeh goes from round in the middle to a cat’s-eye shape on the edges,” Simpson says. “We spent ages replicating that because it’s so visually distinctive. It’s too beautiful not to do!”

— Joe Fordham