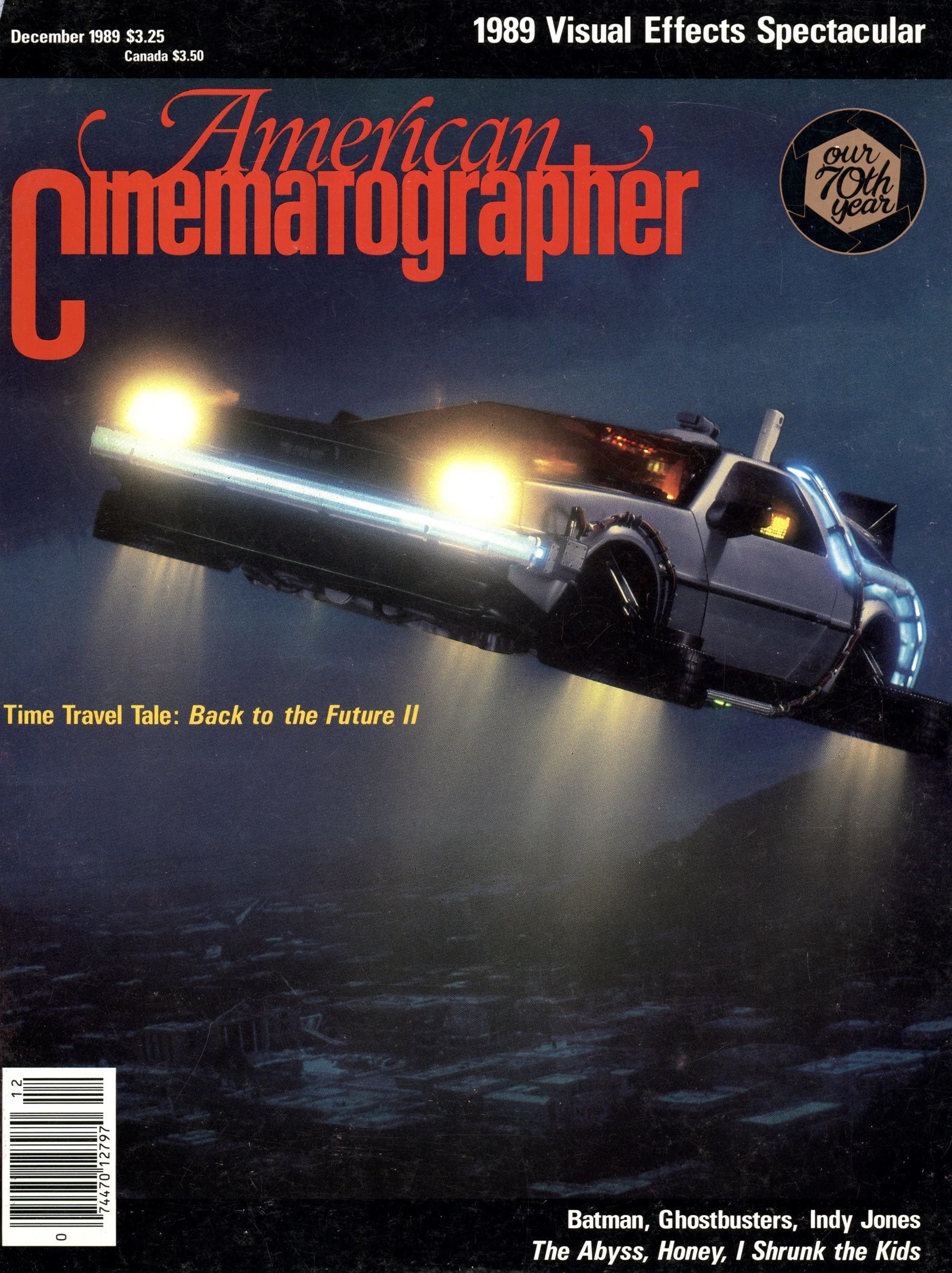

Batman Voodoo Mostly From Britain

Derek Meddings discusses some of the visual work that went into creating the action sequences for Tim Burton's superhero feature.

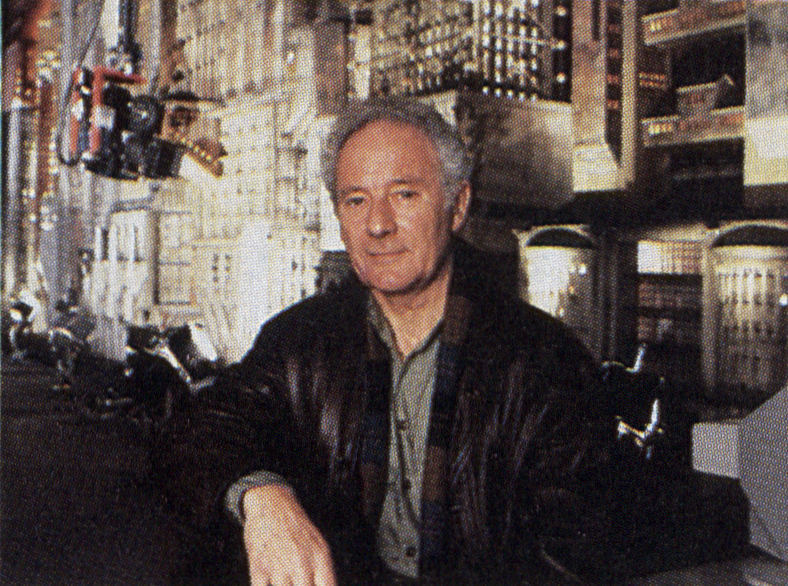

Effects artist Derek Meddings' contributions to many fine Hammer films and the British Thunderbirds and Supercar television series made his name respected abroad, but it was his work on the first three Superman films and in the James Bond series — including Live and Let Die, The Spy Who Loved Me, Moonraker and For Your Eyes Only — which brought him international recognition, and ensured a place with the greatest effects artists of all time. Now Batman soars because of Meddings' breathtaking work.

“Whenever I can do an in-camera optical, I do it. One of the reasons is I love to see rushes the day after the job is completed.”

Meddings was hard at work with production designer Anton Furst on High Spirits when he was approached about doing the elaborate effects for Tim Burton's Batman. When Meddings was hired, he recommended the production also bring Furst aboard as production designer, which made for a happy working experience and a splendid-looking film. "Anton designed everything and my crew and I just copied those designs in our models and miniature sets," Meddings says. "As the production designer, Anton had a special idea of how things should be done and how they should look."

Meddings spent nearly nine months preparing and shooting Batman. While it may sound like quite a commitment to some, Batman’s lengthy production schedule was a welcome relief to the workaholic effects man. "That's the sort of film I like," he admits, "because I don't have to worry about looking for work for a while." Once Meddings set to work, the first order of business was to construct the elaborate models necessary to sell the reality of Gotham City and Batman's amazing assortment of bat-gadgetry, including the Batwing plane. The model crew had the privilege of building miniatures for sequences no one would guess featured miniatures — for example, when the Dark Knight, with Vicki Vale, escapes his evil pursuers by shooting a bolt up into an overhead catwalk. "The live-action part of the shot had them lifting up off the ground, so they just left the picture," Meddings recalls. "The rest of it we did as a miniature: we built the top part of the alley with the buildings Anton had designed. We built a gantry and just pulled our miniature Batman and Vicki figures, which were something like three inches in height, upon wires. Then we had a lot of smoke in there and steam coming out of the pipes, which had to be lazy. That was the main reason we shot at 120 frames per second. If we shot it past that speed, we'd get very fast-moving smoke and it didn't look right. I've spent all my life shooting at 120 frames a second. If the camera's running at 241 think there's something wrong with the camera — it doesn't sound right," he chuckles.

"I gather from the write ups that a lot of people who saw the film weren't aware just how many miniatures went into it," Meddings says proudly, "which is a compliment to us. If people can say 'Now, that miniature you did,' if they can spot it, we've failed because it should all go together and nobody should be aware that they're miniatures."

In keeping with this philosophy, Meddings achieved a rather remarkable blend of live-action and. miniature effects photography in the sequence where the Batmobile crashes through the gates of the Joker's factory hideout just as the factory blows up. "We did that as a split miniature," Meddings reveals. "We built the factory as a miniature and used an area of Pinewood Studios dressed up to look like the entrance to the factory for our live-action sequence. Then we just composited the model in on the top of it. It was a very simple split really. When I say simple — nothing's simple. You've got to get the right balance.

“If we had built it as a foreground miniature, it would have slowed down all the foreground live-action, so the Batmobile and everything else would have appeared to be moving too slowly."

“Again, we couldn't do the shot using a foreground miniature, because we had to shoot the factory blowing up at 120 frames a second. If we had built it as a foreground miniature, it would have slowed down all the foreground live-action, so the Batmobile and everything else would have appeared to be moving too slowly."

The epitome of the Dark Knight's genius, the Batcave, was visualized by production designer Furst as a dark, bottomless, twilit region somewhere deep under the earth. Meddings' crew supplied a number of truly impressive matte paintings to augment the beautiful set that had been built at Pinewood, and to help bring Furst's vision to the screen.

"Dear old Anton did a great job," Meddings says, "but of course, like all of these shots, they couldn't build the whole cave, nor could they get the proper depth in the cave. So all the shots where you see the entirety of the cave were done with several matte paintings. There were a number of different camera angles. We had three people doing them. One painting was done outside by Doug Ferris. Ray Caple did some, and one of our boys, Leigh Took, did about three of them, and he was a newcomer to the team! We did them all on glass — the sort of old way of doing it."

One of the most exciting shots in the film for fans of the Batman comics was one in which a bit of cartoon animation was used unexpectedly to create the effect of looking down on Batman standing on a ledge from an impossibly high perspective. The shot had a wonderfully stylized look to it that immediately created the appropriate comic book mood. "That was a very tricky shot," Meddings admits. "When I originally saw it was written into the script, I kept ignoring it because I didn't know what to do. I thought that on the day we actually set it up, I would think of a way to do it!

"We were shooting down the height of our 35-foot cathedral model, which we had laid on its side. Originally, we rod-puppeted a miniature Batman — we had him turn and appear to walk back into the cathedral out of camera view. It worked, but it didn’t. It nearly came off. So we decided to use cel animation, which was done by one of my boys who's into animation, Peter Chang. He's a very clever animator, and he also added all the lightning and steam effects to the shot. The bottom of the shot was a matte painting."

Meddings considers the miniature set with its 40' backdrop somewhat small by his standards, compared to similar sets he'd built for Santa Claus: The Movie and the Superman films. "On those films, it was easier because we could just photograph New York and use a very large transparency — sometimes 60 feet across — as our backdrop," Meddings says. "But in this case, the backdrop had to be an entirely hand-done painting because the skyline of Gotham City was so unique."

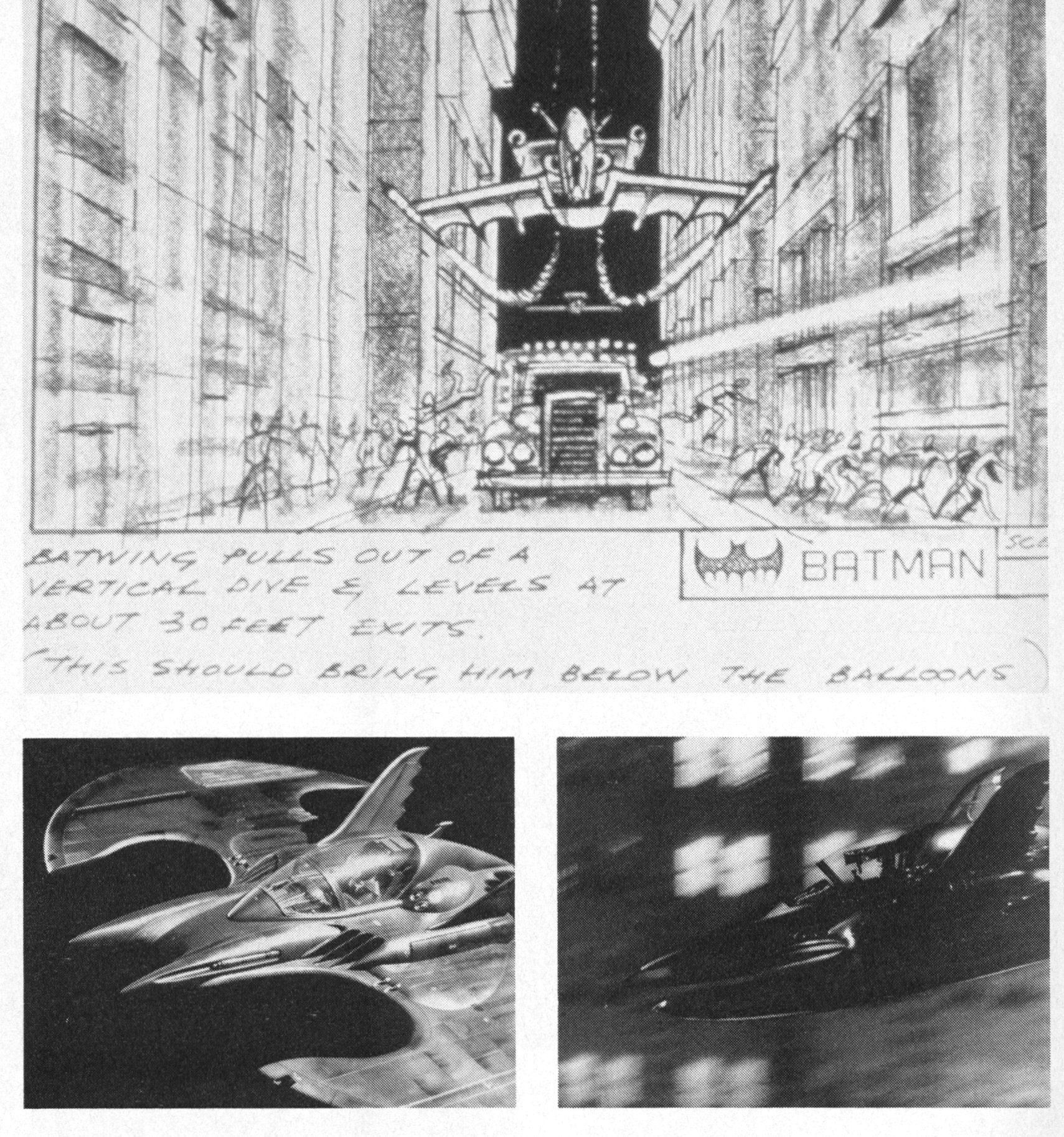

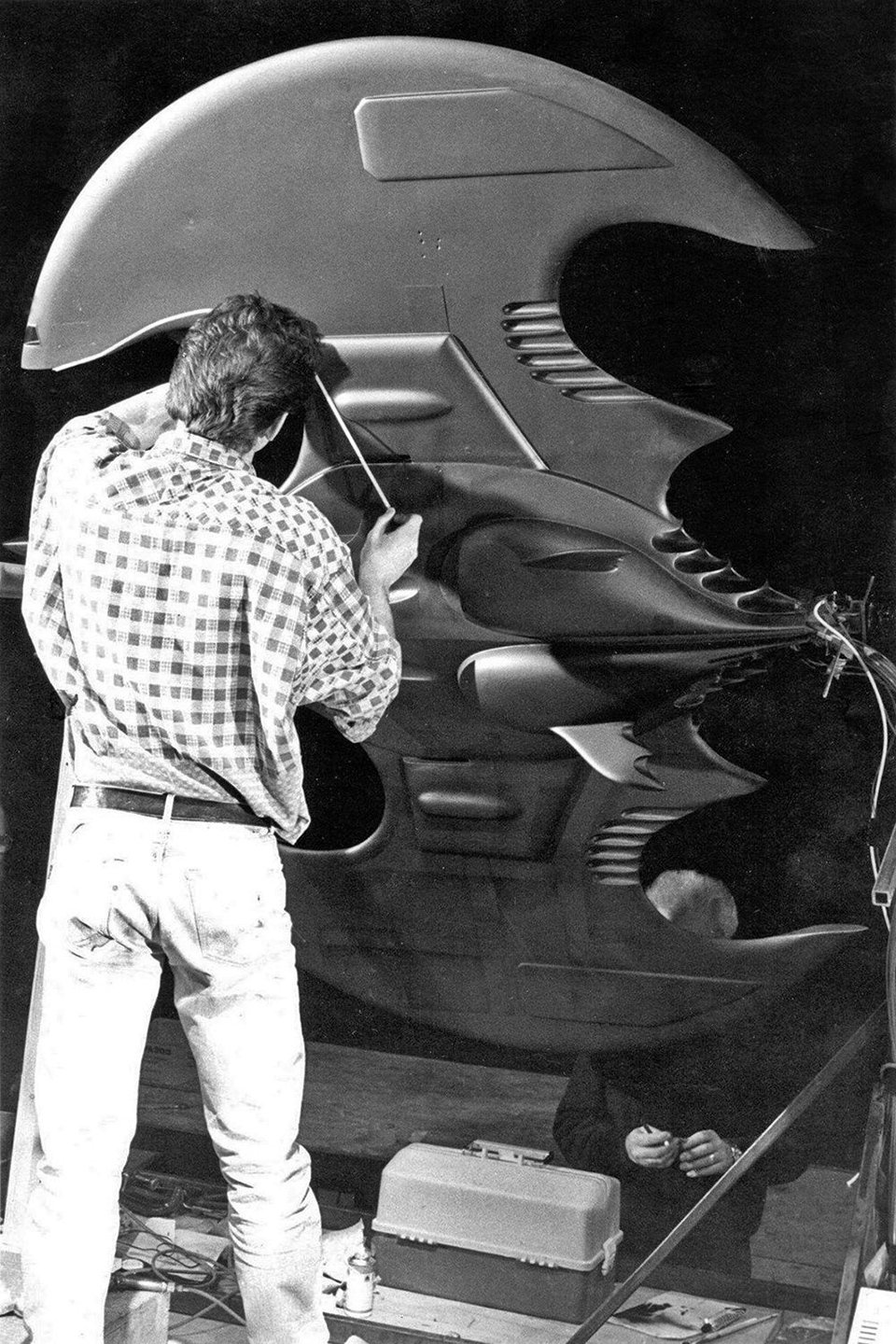

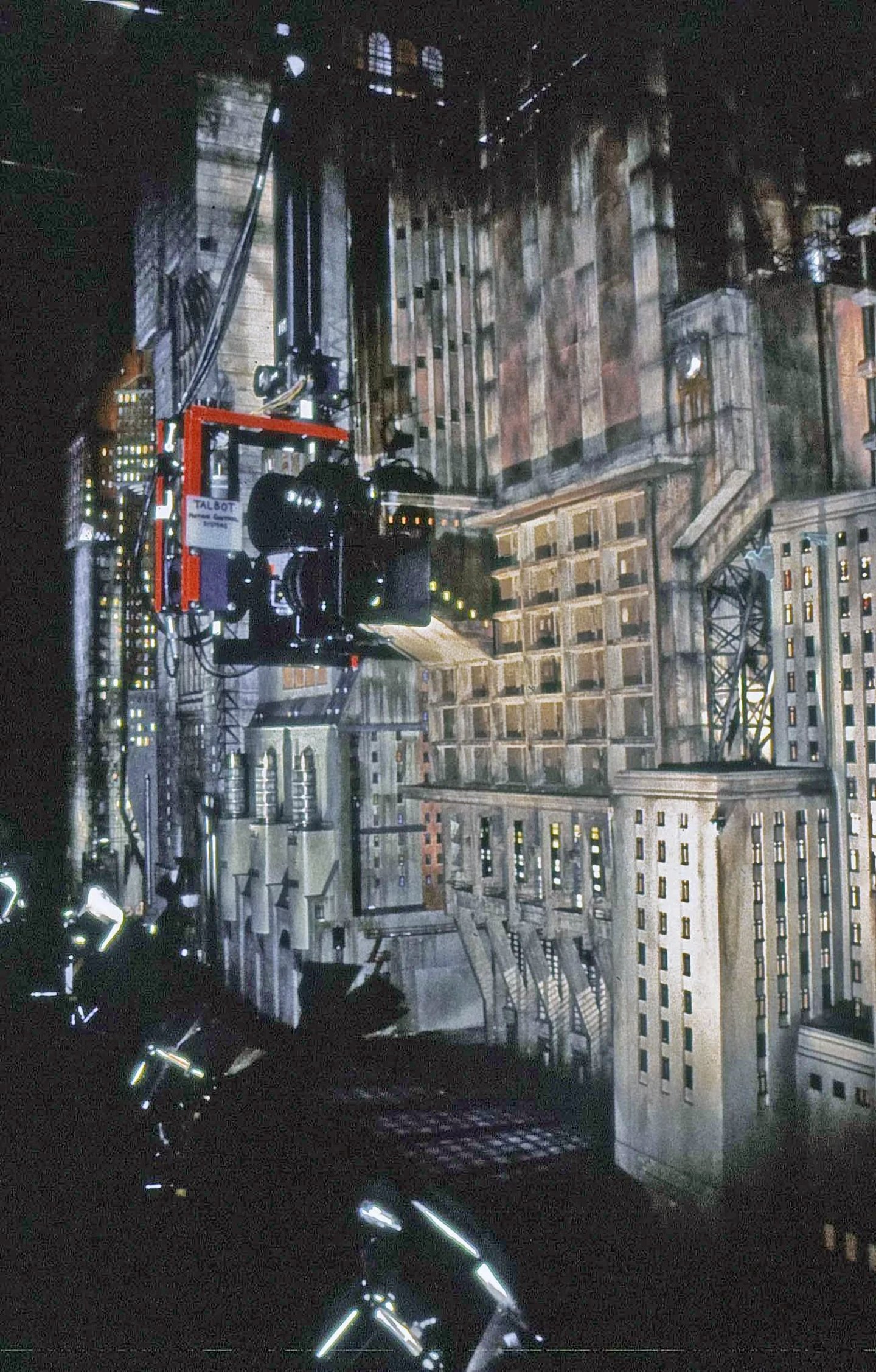

Working over a four-month period, Meddings' son built a large, 1/12-scale miniature of Gotham City's main drag for the scene in which the Batplane zooms through the corridor of skyscrapers. "The buildings in the Gotham City set were quite tall," the elder Meddings recalls. "They were all about 19 feet high, and the street was very narrow because we wanted to create a claustrophobic atmosphere."

The narrowness of the miniature streets created a series of problems for Meddings' crew when it came time to shoot the Batwing's flight through Gotham City. "We couldn't use a snorkel," Meddings explains, "in that shot where the plane flies over the parade and comes very close to the cathedral but then peels off and misses the cathedral. When we laid the shot out roughly just to try it, we realized we were going to have problems. When we started to do the bank, simulating the Batwing's veer to the right, the snorkel hit the building. We ended up building the motion control camera rig so as it traveled down the street, it was actually climbing. That was just as good as using a snorkel really. Fortunately, there was supposed to be a climb in that shot."

The Batwing crash was actually shot live action at 120 frames a second, with the model flown on wires. "We had little charges in it so when it hit the road, we could explode the charges — Whish! — blow off the wings and do a certain amount of damage. The trouble was it had to match with their live-action shots where the wreckage of the Batwing was scattered on the cathedral steps. We would have liked to do our shots first, but they did their part first because the schedule didn't quite work out, so my big problem was to get the Batwing model to actually end up on the steps of the cathedral in the same place as the full-scale mockup, facing the same way."

Meddings' crew built two different scale plane models, one for the long shots and one — and only one — for the crash: "For the very long shots, we had a 1/12-scale Batwing, which was very small, it worked out to be only 6 inches across. Then we had a 1/4-scale Batwing for the crash. We only had one of those. It took so long to build, what with the schedule and the time and also the budget, we had to get the crash with one Batwing. But in actual fact, we didn't get it in one! We got most of it in the first shot, but we needed other cuts to make it convincing, so we had to repair the Batwing within a half-day and do it again."

“I painted all the clouds for that. I used the old trick of painting on plastic so we could get a really jet black sky and put all the stars in.”

The film's signature shot was done in miniature and then optically composited. In it, the Batwing hovers in front of the moon, over a sea of clouds that seem to have drifted in from a Maxfield Parrish painting. "I painted all the clouds for that," Meddings says. "I used the old trick of painting on plastic so we could get a really jet black sky and put all the stars in. First, I sprayed the clouds onto plastic, then we put dacron clouds in front of it, like the old cotton wool, and lit them from underneath. To add the stars, we wound back the film and shot them separately, so all the stars look nice and clear. It was Anton's idea — a great idea."

For the film's climactic battle between the Joker and Batman inside the cathedral, Meddings built a 35' deep miniature belltower, into which various objects — a church bell, Vicki Vale's shoe, one of the Joker's henchmen — would fall. "Though our model was 35 feet in height, to give it a real feeling of depth, we photographed it, then reduced the photograph and put it on the floor," Meddings explains, "so the end of the model was a photograph. The henchman who fell down the stairs was shot blue screen and then matted into the shot. The only tricky part was putting it together! Fortunately, I've got two optical lads who are really very good at it, Neil Sharpe and Anthony Hamilton. It would drive me crazy, it's too mechanical, but they just loved it.

"If I can get away without using bluescreen," Meddings admits, "I do. As much as I love the process, there are always times when some little thing goes wrong. You don't quite get it put together properly. It's become an art form now, and it's being used more and more. I think people are getting more professional at putting these together, but when I worked on the Thunderbirds series, there was no way that we could put opticals into an hour-long program — we only had 10 days to actually shoot those episodes. So, ever since, whenever I can do an in-camera optical, I do it. One of the reasons is I love to see rushes the day after the job is completed.

"When you do bluescreen, you don't see anything for three months. I'm always a little nervous until then because although I think I've done everything right, there's always that chance that something didn't quite work. If you're doing an in-camera optical, you see it the following day. If there's something that's not quite right with it, you can go back again and do it very quickly."

Consequently, the other objects which plunged into the miniature belltower, like Vicki Vale's shoe and the church bell, were miniatures in scale with the staircase model. They were dropped through the set and shot at high speed, live-action. "The bell was a real brass bell that we found somewhere, so of course, it had terrific weight to it," Meddings relates. "We just let it free fall. It was so heavy that there was no way it was going to bounce off the miniature staircase, which was made out of a very light, softwood. We lined the heavy bell upon a quick release, so that when we let it go, it just went down and took all that staircase away with it as it fell, shattering the whole lot.

"We had three cameras, shooting at 120 frames a second," Meddings continues, "because it wasn't something we wanted to try to do twice! It was a nicely built miniature and to do it again would have been quite a task. When you build something like that, you box yourself in. The miniature had to be very strong and supported all the way around so there would be no shake to it when the bell hit the staircase. Once it was built and painted, we couldn't get in to work on it again. If we ever had to touch anything up — sometimes you see a little piece of white wood that hasn't quite been painted — we had to do it with a paintbrush on a long stick.

"Getting the three cameras in position was the biggest problem" he adds. "We had one camera looking down the shaft and two cameras cunningly hidden behind pieces of the staircase, looking up. We had to make sure those cameras weren't spotted by that high shot."

The ultimate battle between Batman and the Joker occurs on the ledge above the cathedral, where Batman and Vicki Vale hang on for dear life as the Joker's henchmen attempt to rescue their leader with a rope ladder hanging from a helicopter. "That sequence was all done with miniatures," Meddings points out. "They only used the real helicopter for the close-ups. They put it up on a big rostrum on the backlot at night and they shot the inserts of the goons looking out of it and throwing the ladder. Everything else was done with our miniature helicopter, which we flew on wires. It was about five feet in length and had a built-in motor that worked the rotor and flashing lights.

"Since we were shooting at about 96 frames per second we had to have a motor that really made some revolutions, otherwise the rotor would have appeared too slow. We put a tiny unit inside the model to release the ladder so when they cut to the wider shot of the helicopter you see the ladder drop. The miniature ladder was made of very fine nylon, and all its rungs were made out of lead so it would have the proper weight when shot at a very high speed. When they were hanging on the cathedral and the ladder in longshot, again we had very small, three-inch figures of Batman, Vicki, the Joker and his goons."

The film's memorable final image is of Batman standing atop a huge building as the camera moves up and up and up and the Bat-symbol blazes in the night sky. The shot was accomplished via a clever blend of miniature and blue screen photography and animation. "We laid some miniature buildings on their sides, then we placed the camera on a crane and tracked up the buildings. Then we did some soft dissolves so we could go from the live-action building to our miniature building because the shot started in the street below. The camera in the live-action shot moved up as far as it could, then we took over and soft dissolved the upper part of the building in. Then we traveled up further, went over a gantry, and did a soft dissolve into Batman, who was shot bluescreen, live-action. Finally, the clouds and the Bat-symbol were put in afterward with animation."

Meddings, a 35-year veteran of the movie business, grew up around the studios in England and always knew he wanted to work there. "My mother was a continuity girl and stand-in for Merle Oberon in one part of her career, and my father was a master carpenter at the studio, so of course, I wanted to be in the film industry," he smiles. "I trained as an artist — not a very good one — but I knew I wanted to make movies. After I did my two years of national service in the air force, I managed to get a job at Denham Laboratory painting titles to films, which drove me crazy because I hated it. But it was a way in. Then I was very lucky, because I met Les Bowie, the great effects man, and he took me under his wing. I wanted to train as a matte artist, and he said ‘Right, join me.’ So I worked as Les' assistant for many years, and the first films we did were all Hammer films."

Had the choice been left to Meddings, he might have remained a matte painter, but the economics of the British film industry at the time didn't provide steady work for matte artists, so the young apprentice began to learn the tricks of the effects artist's trade from his mentor, Les Bowie. "I thought the process of matte painting was absolute magic," Meddings explains, "but, unfortunately, in England at that time a matte painting cost 100 pounds and film companies couldn't afford it unless they were making a big picture, so there always came that time when there wasn't any work in the matte painting department. But Les, being a very versatile man, used to get involved in doing miniatures, so we would do them together.

When we didn't have any miniatures to do, he used to take me out onto the sets and we would do the live action. So I had a really good grounding and I learned from Les all the tricks that I'm doing now. He did them years ago.

"Les was never really appreciated, unfortunately," Meddings sighs. "One of the unsung heroes. It was very unfortunate that he died at the end of Superman. I don't think he ever knew that he won an Oscar. I remember when I was quite young and I was doing Thunderbirds, he used to say to me, jokingly, 'If you ever win an Oscar before me, I'll kill you.' And we won it together on the Superman picture, and he never knew."

Meddings may go down in the annals of film history as the man who bequeathed superpowers to more screen heroes than any other, from Superman to James Bond. Ironically, he rarely enjoys the films that have given so much pleasure to his fans. "The only reason is, of course, I'm too close to them," he explains. "If I see the film six months after I've done it and I've forgotten what I've done, then it all comes up as a nice surprise. But Batman I really did enjoy. Safe to say Les Bowie would be very proud of his apprentice."

Access the every issue of AC and every story from more than the last 100 years with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.

Click here for more archival stories from American Cinematographer.