Geoffrey Unsworth, BSC and the Photography of Superman

An incisive analysis of the photographic challenges and techniques involved in this major motion picture — and a heartfelt tribute to a legendary cinematographer from his co-worker of two decades.

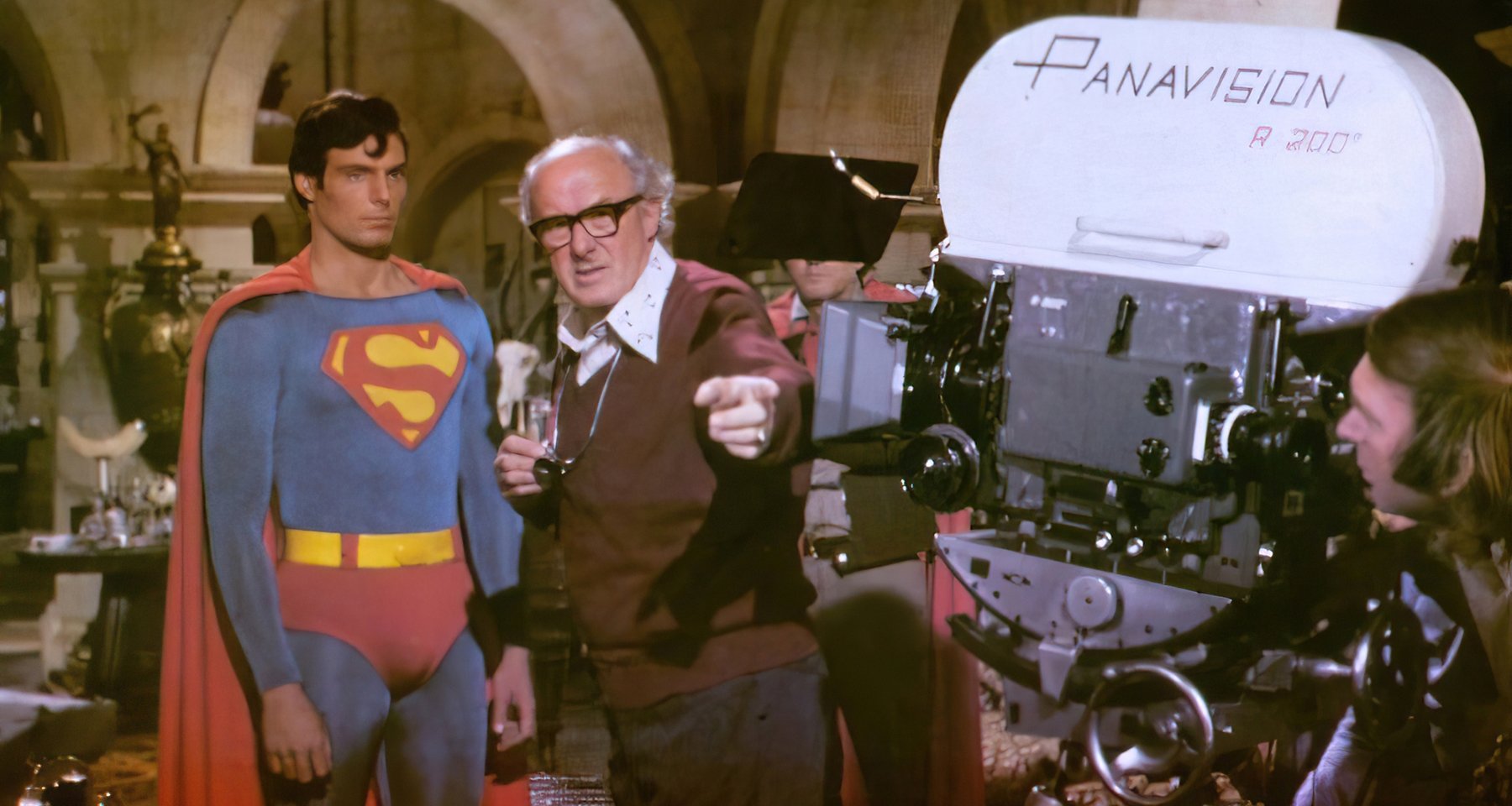

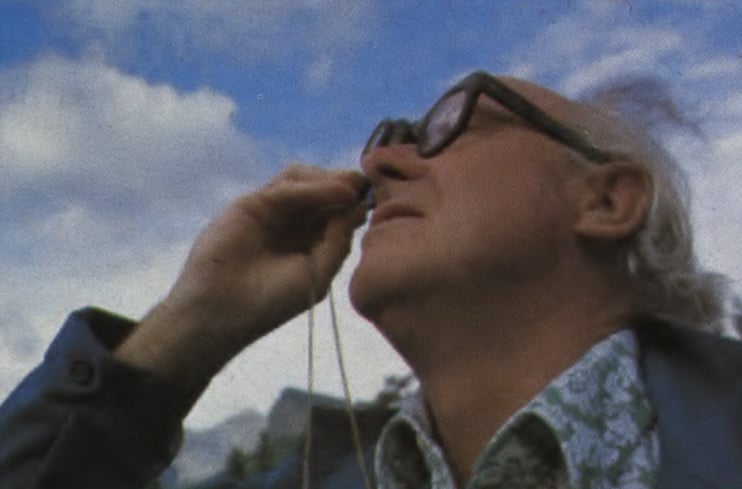

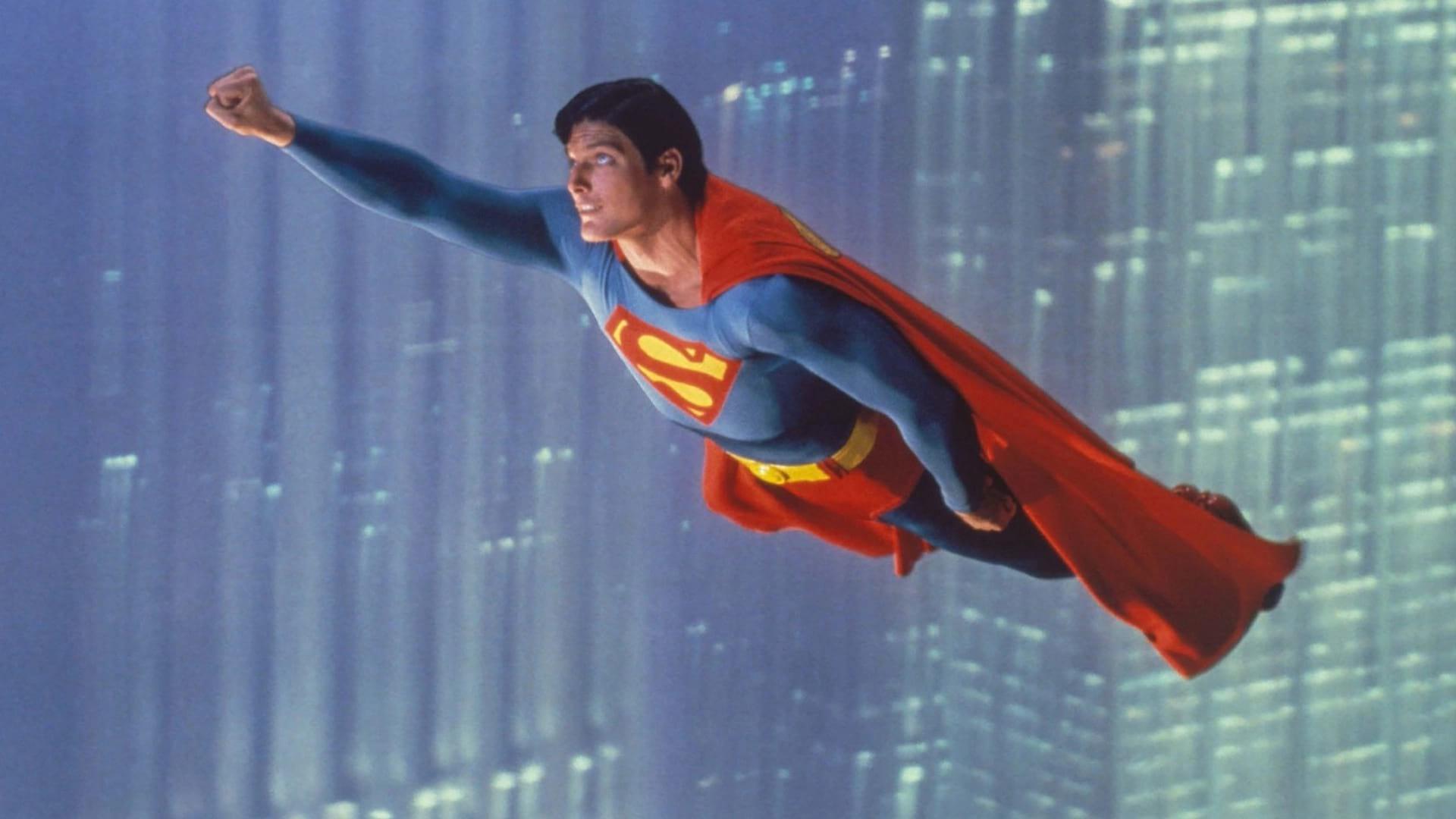

of screen “geography” to Superman

(Christopher Reeve). He was unfailingly kind and helpful to co-workers — especially those new to the film medium. At right is the author.

By Peter MacDonald

EDITOR’S NOTE: At the time that Academy Award-winning cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth, BSC died of a sudden heart attack while filming in Paris recently, David Samuelson had just made arrangements to fly over and interview him relative to his work as director of photography on Superman. Since such an interview was no longer possible, Peter MacDonald, for many years operator and assistant to Mr. Unsworth, very kindly agreed to discuss not only Mr. Unsworth’s work on Superman but the working methods and artistry which established him among the very top cinematographers of all time. The article which follows has been extrapolated from the resultant discussions between Mr. MacDonald and Mr. Samuelson.

As an operator, I would say that I worked on about 30 features with Geoffrey Unsworth, as well as quite a few others in the capacities of focus-puller and loader. The first film I did with him was called A Night to Remember, which was too long ago for even me to remember — but it must have been 20 years ago. So I have devoted my entire career basically to working with Geoffrey and, up until nine months ago when I had to leave him to do another film, I had spent literally the last 12 years working non-stop with him. Included among the features we worked on together were Superman, A Bridge Too Far, Cabaret, Murder on the Orient Express, Return of the Pink Panther, Cromwell, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Beckett, Half a Sixpence, Three Sisters (which we were very proud of, although it didn’t hit the headlines) and many others.

If I may, I should like to extend this discussion beyond Superman to permit a wider examination of Geoffrey’s skills and techniques as a cinematographer. He was an intuitive cameraman, as he himself would readily have admitted, although no one would ever have believed him. He wasn’t a highly technical cameraman. He believed in his instincts and his gut feeling for photography.

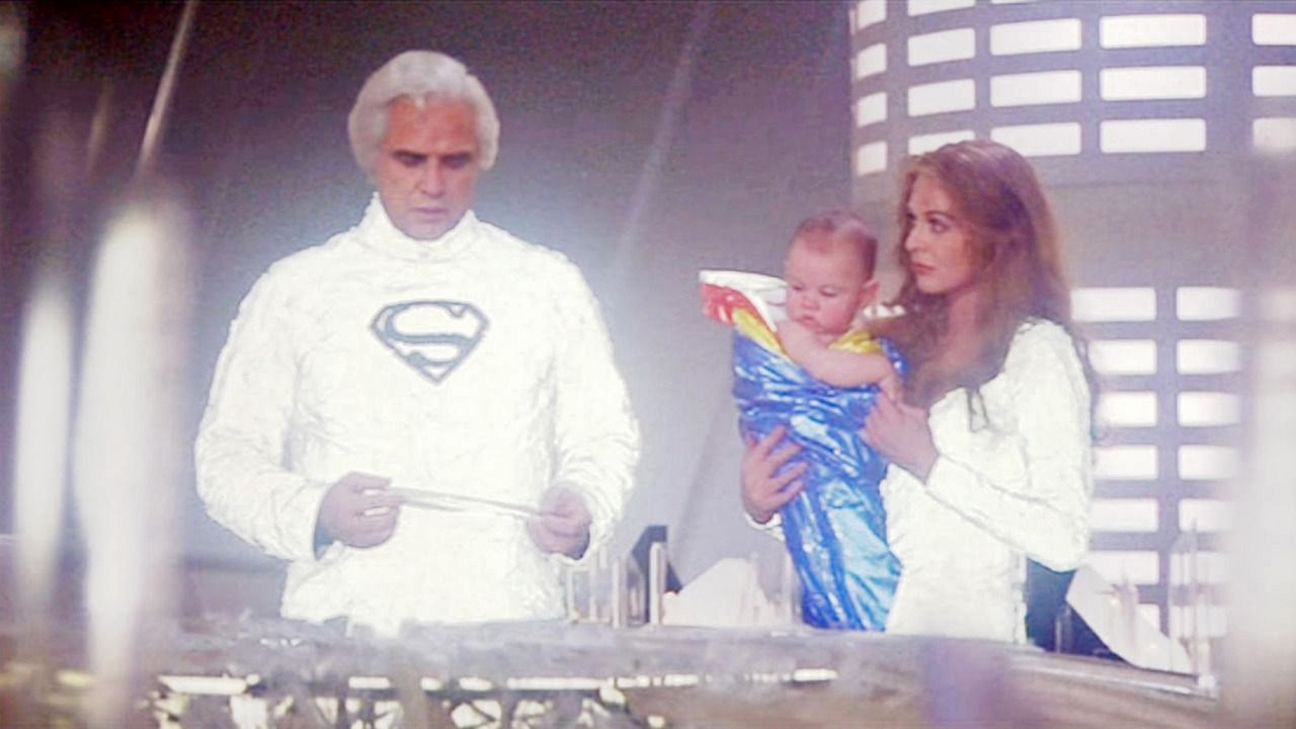

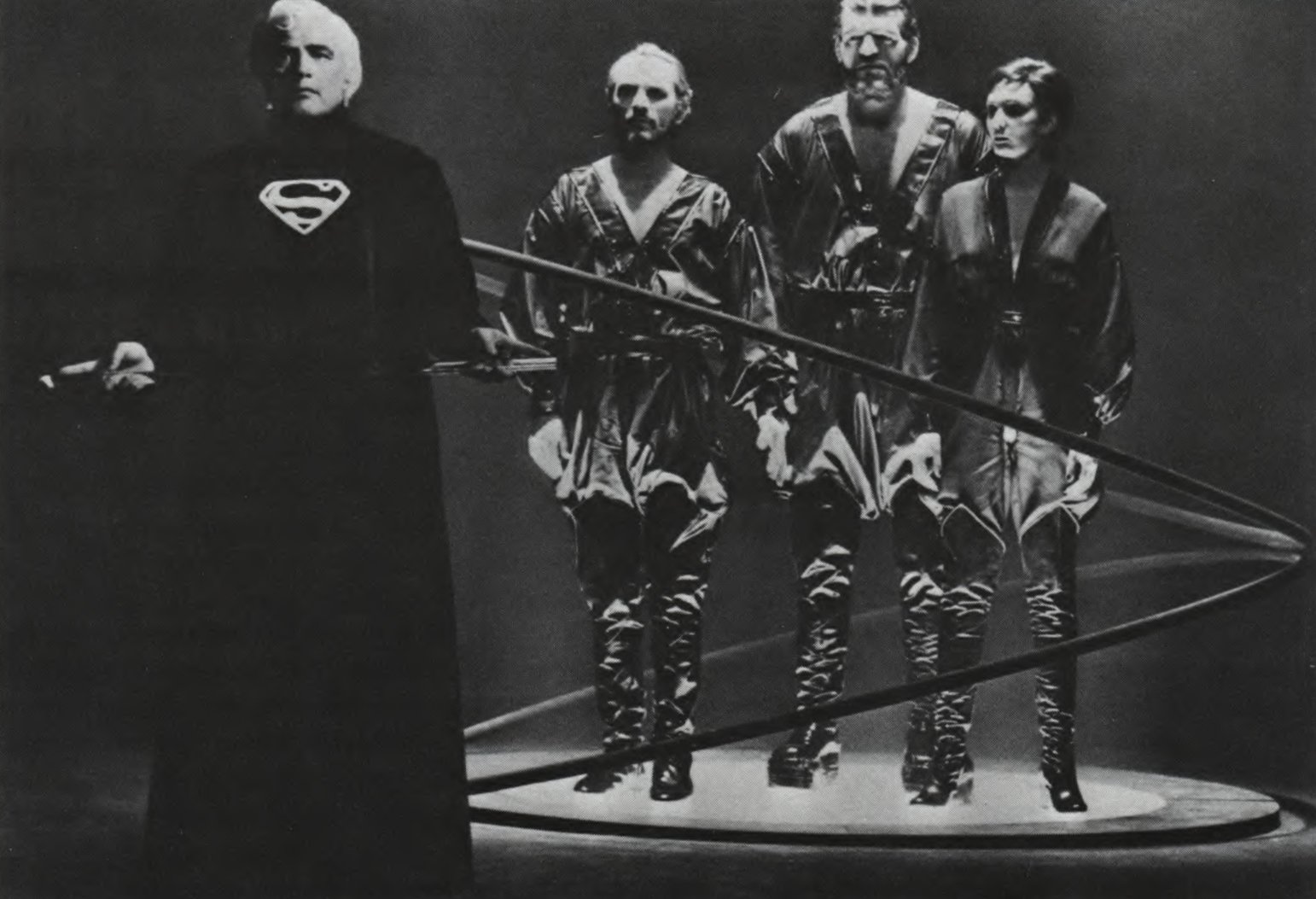

I should say that there are very few cameramen who are quite as daring as Geoffrey was when it came to taking chances. I have seen many directors who, when looking through the camera (after we had filled a room with smoke and put the filters on) turned slightly pale at what Geoffrey was up to. A very good example of this was the Krypton sequence of Superman, in which all of the artists were wearing costumes made of front-projection material, which, in combination with the lightboxes made up for us by the Samuelson organization (and which were on dimmers) made it possible, if you wished, to wipe the artists right off the screen. Now, remembering that the artists, in this case, were people like Marlon Brando (who didn’t come cheaply), there was obviously cause for worry. You had to hit a happy medium of photography and have a recognizable image, which I feel that Geoffrey did to perfection. But it took an awful lot of guts to take it as far as he did, and that was one of his strong points.

Geoff would never talk about what he was doing, but he loved every moment of his work and dedicated everything he had to it. I’m sure that any one of 20 or 30 directors would back me up when I say that Geoff would never influence a director against doing a particular shot because it would be difficult for him. He would chew his viewing glass and walk away and maybe kick a box, but he would turn out the shot asked for, although it sometimes seemed an impossibility. Having had experiences with some other cameramen, I have seen them try to influence a director out of a shot because of difficulty to them. Geoff would never, never do that — which I think says an awful lot for him.

“As an instinctive cameraman, Geoff was really like an artist of the past — an Impressionist.”

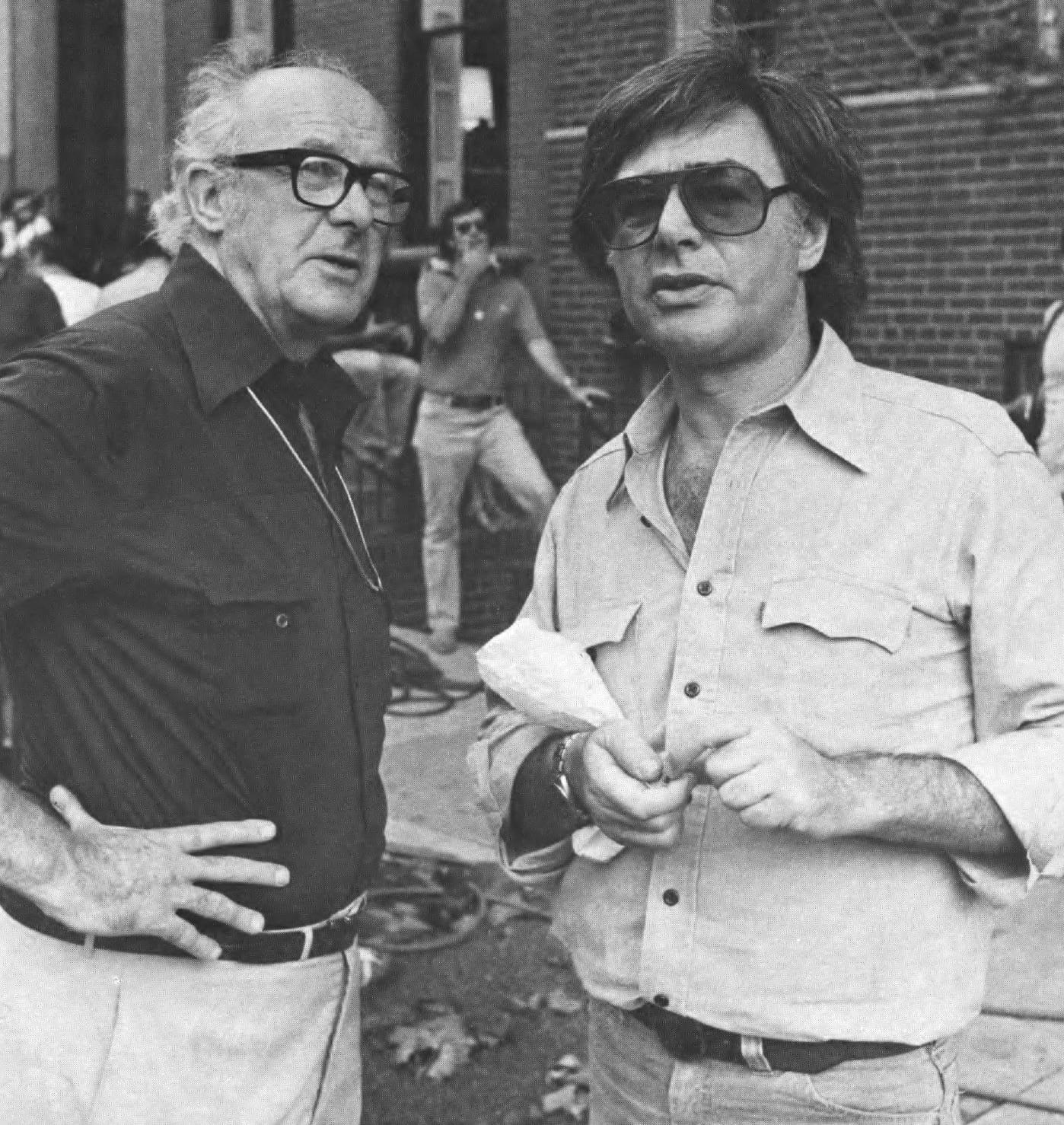

Peter MacDonald and Unsworth.

Geoffrey didn’t always work on huge-budget films, as everyone thinks he did. We worked on films such as Three Sisters, directed by Lord Laurence Olivier, and Dance of Death. These were three-hour films that were made in three or four weeks. You can’t make films like that with quality without having very involved shots. We were doing 9 and 10-minute tracking shots ending up in many close-ups. When you have to come to close-ups of people like Olivier and Joan Plowright, each one has to look as good as if it were shot as a separate closeup. These are difficult shots to do. In the old days, people used to brag about doing a 10-minute take, but we had to turn out sometimes one or two of these a day because of the short schedule.

As an instinctive cameraman, Geoff was really like an artist of the past — an Impressionist. It was always amusing to me as his focus-puller, and later as his Operator, to see him choose the very best lenses that Samuelson or whoever we went to could supply — and throw out anything that wasn’t perfect — and then for the rest of the film proceed to destroy the image up to the point that he wanted to. He had to start off with the very best equipment — equipment which he could trust — so that from there on in he would know how far he could go with filters and back-lit smoke in order to destroy the image to his taste.

When we were making Cabaret there was a man on the set from 7 o’clock in the morning (we used to start work at 8 o’clock) and that man’s job was to fill the stage completely with smoke. It wasn’t just a little puff of smoke; the whole stage was full of smoke that stayed there all day long at a consistency that Geoff would choose. The more people complained about it, the more you got a twinkle in Geoff’s eye, because he knew — as we all learned — that the results were exactly what they should have been, and eventually got him the award he so richly deserved from the Academy, and which meant so much to him.

On Cabaret we had a lot of complaints from the Coast, as it were. They were very upset with Bob Fosse and Geoffrey and myself, to some degree, in the way that we were shooting the film. They wanted a glossy musical and Geoffrey and Bob had decided that it should be something that you could believe in — as if you were actually there, watching a part of life. Every Friday night the phone used to ring from Los Angeles and we would have quite a lot of static, but I must say that Geoff kept to his guns and Bob Fosse was, in both Geoff’s and my opinions, one of the best directors that we had ever worked with. He stood by Geoff right to the end and I fee! that the result proved that they were both right.

On A Bridge Too Far, which was shot in Holland, the mass parachute drop was covered by more than 20 cameras, some of which were mounted on paratroopers’ helmets. The coverage on that sequence and the planning that went into it were quite incredible. A lot of the camera people were on very long lenses — 1000mm and 800mm with doublers. On two of the drops, we were lucky with the weather conditions and could use our fog filters, but on the third drop, Geoff told the operators over the radio to remove their fiIters because the foggy weather was a natural diffuser. In the final cut, you couldn’t tell the difference between the stuff with and without filters. That one drop was the first time in 14 years that I had seen Geoff shoot without filters, but he wasn’t a dogmatic type who said, “I shoot with filters and that’s it.” He knew that in this case the conditions would do what the filters had been doing for him.

Regarding his use of filters for Superman, they were used heavily in the opening sequence, which takes place on the planet Krypton when Superman (or Superboy, as he is then) is sent off by his parents to safety on Earth. There the effects could really go over the top. As I mentioned before, all the actors wore uniforms made out of 3M front-projection material that was crinkled up. We had camera-mounted lightboxes on dimmers so that we could bring out their uniforms (and parts of the background that had 3M material) as we wished. There was a lot of smoke around, too. Visually, that really was a separate section of the film.

However, once Superman landed on Earth, Dick Donner wanted the picture to have a straighter, comic-book look, so most of the remainder of the picture was shot with just a light fog filter. We knocked just the edge off it and Geoff’s photography did the rest. After having seen the film, I feel that it works immensely well.

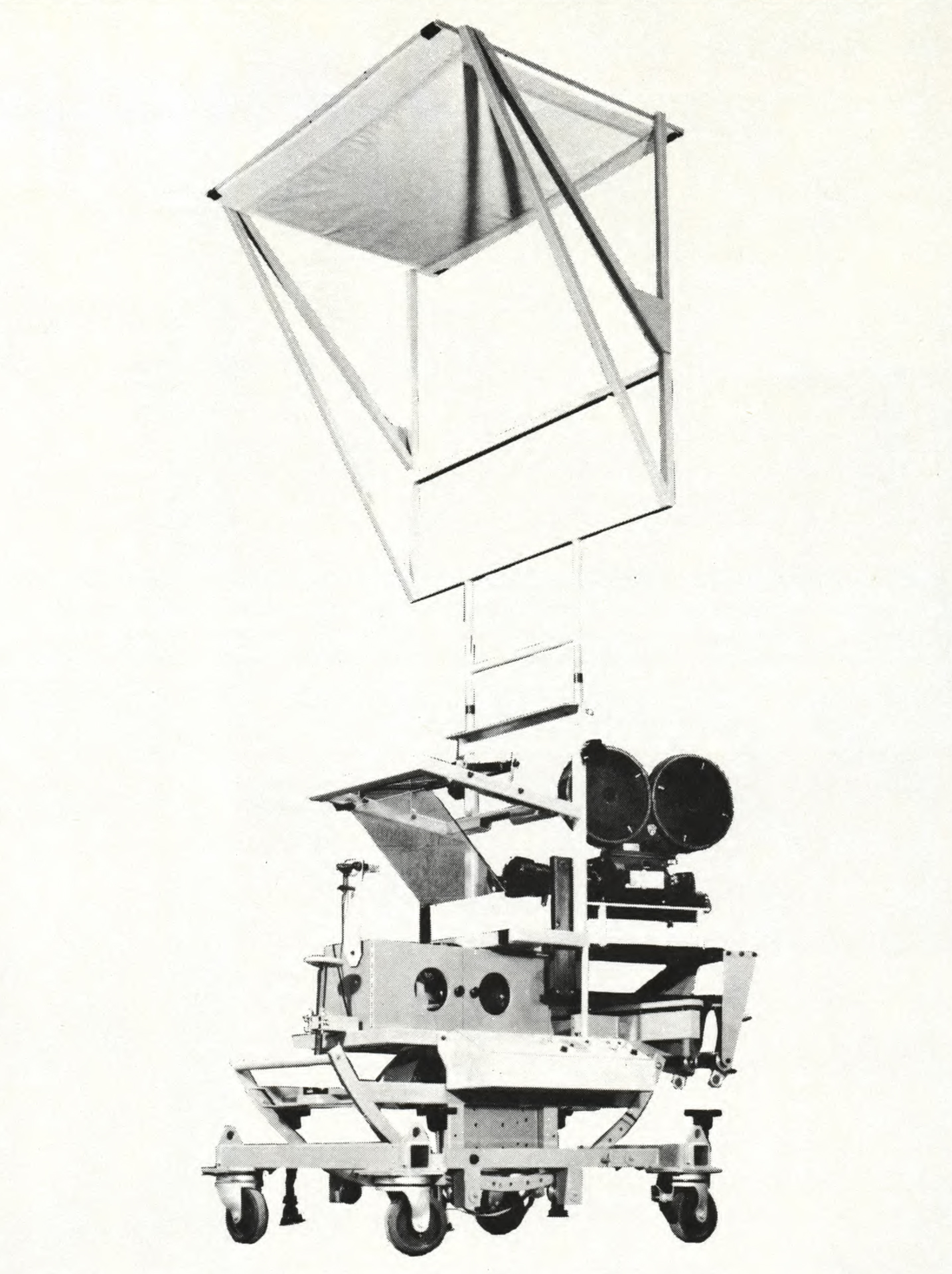

The lightboxes we used had a light which shone through a piece of semi-silvered mirror placed immediately in front of the lens — like a front projector without any film or slide in the gate, as it were. The lightboxes were like special matte boxes with bulbs in them.

Geoffrey had the idea of using the 3M front-projection material on the Krypton planet sequence, and while he and Dick Donner were away scouting locations in America and Canada, he left me in England with the task of working out the best way of doing it. I took advice from Gerry Turpin, who was amazingly helpful, but anything that Gerry had at that time didn’t quite work for what I felt was needed on the film. I went to Samuelsons and spent some time with their engineer, Derek Lee, and John Campbell, our assistant. What we needed was something that would fit onto a camera. It had to be something that you could pan or tilt without any great worries, and something that would be simple, yet effective. We would eventually have to make 9 or 10 of these.

dual-screen front matte projector, fitted with the Zoptic (zoom optic) special effects device,

which gives movement in-depth to a subject without the subject itself moving at all.

I experimented with everything possible during the two weeks that they were away. The end result was a box that would fit on the front of the camera and which incorporated a semi-silvered mirror set at a 45° angle, pointing upwards towards a lamp. I was worried only about whether we were going to get into terrible trouble with backlights, because of Geoffrey’s love of backlight. The problem of keeping lights from shining directly into the lens was always terrifying to any focus assistant who worked with him. But the device did work. We put two long 1250-watt quartz strip lights in each unit and each unit was on a dimmer, so we had full control. We also had to incorporate some heat-proof oven glass to protect the semi-silvered mirrors and the camera from the heat.

Because a lot of the shooting involved multi-camera set-ups, we set the brightness by eye for each shot. Even on the silent stage at Shepperton Studios, which has a diagonal of nearly 300' (and which was the biggest stage in Europe until the 007 Stage was built at Pinewood), we were able to light up someone at the far end of the set and to pan and tilt and track at the same time. Also, of course, we were able to use colored filters and many other things. It was tremendously successful.

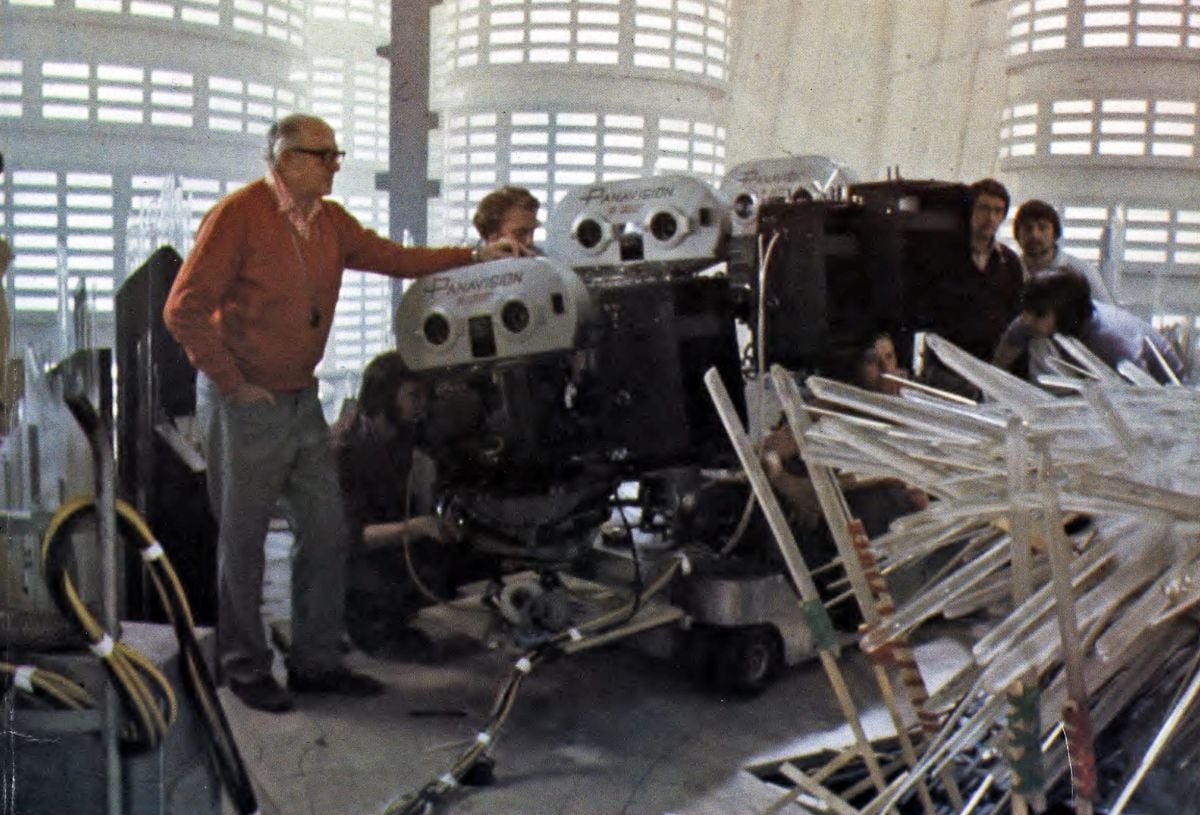

“It was felt that there was no way of matching what either the baby or even Mr. Brando might do, so we had a three-camera setup on one Moviola dolly.”

Superman often was a multi-camera (and certainly a multi-unit) production. At one time I think we had nine separate units shooting all over the world. In the sequence where Marlon Brando is shown with the baby who is supposedly an infant Superman, it was felt that there was no way of matching what either the baby or even Mr. Brando might do, so we had a three-camera setup on one Moviola dolly. We arranged it so that we could fit two PSR cameras on the jib and one on the side — all of which had individual lightboxes. This made it possible for us to do a fairly involved tracking shot around Marlon and the baby while the dialogue was being spoken and Krypton was breaking up so that in one take we could get everything we needed and it would cut perfectly. There would have been no other way of matching what would happen during that shot — no way at all — because with babies (and even with some adult actors) it’s very difficult to match.

The three cameras were tracked by Frankie Batt, who was our grip, under terrific strain. In the final cut of the sequence, a piece of each camera shot was used, and they were all obviously tracking at the same speed and photographing the same things. All three shots worked perfectly together.

super-villains (Terence Stamp, Jack O’Halloran, and Sarah Douglas) as they are being

judged for their crimes in the Council of Elders on the planet Krypton.

Because of the short time that Marlon Brando was going to be with us, the sets in which he was to appear would always be pre-lit and pre-cameraed. That is, after the normal working day we would then go to the next set, where we would set up three cameras (or however many cameras would be needed) and Geoff would light a stand-in. As a result, when we finished in one set there would be no time loss. We could go to the next set and be ready to shoot — and there was an awful lot of Brando to shoot over a short period of time. It worked very successfully that way. We saved time and got results.

Geoff Unsworth was never especially keen on hand-held photography, although we did some films that needed hand-held work. Many people believe that hand-held photography is going to make things work more quickly, but it doesn’t always. We’ve done films like The Magic Christian with Peter Sellers in which there was a tremendous amount of hand-held because it was the type of film that could go hand-held and not disturb. Geoff and I were always very determined that the audience should not be disturbed by any photographic effect or use of the camera. I know that people often come out of rushes, after having seen an especially complicated shot that was done on the stage, and they are disappointed because they haven’t seen camera moves, but we both felt that camera moves should go with the actor and should never be obtrusive — unless, of course, you were really trying to make a point.

We did other films that called for considerable hand-held work but Superman didn’t call for it, nor did A Bridge Too Far. There is a shot in Cabaret of which I am personally very proud. It is a high-speed hand-held shot that goes completely around the stage without your even knowing it was hand-held, because of the way that it was timed and done. So we used hand-held photography, but we didn’t over-use it because it was the trendy thing to do.

It should be remembered that the Panaglide was just coming in when Superman started production and, although we tested it and spoke to Donner about it, there were no situations in Superman that might have required it. We could always track, because we never had stairs that had to be climbed. We did some complicated tracking shots in the Daily Planet office on an Elemack dolly and they could not have been done better on anything else, not even a Panaglide. With a good grip and an Elemack and a smooth tracking floor you can do an awful lot, if you plan your shots properly.

Geoff was always concerned — as any lighting cameraman must be — with the camera set-up, but because of our long period of working together, I was allowed a very free hand to work with the director in finding and discussing the setups. Geoffrey kept not too far in the background and was always completely tuned in on what was going on. He would let the operator and the director discuss setups, but he was there for advice and obviously would speak up if he disagreed with something or felt something else would be better.

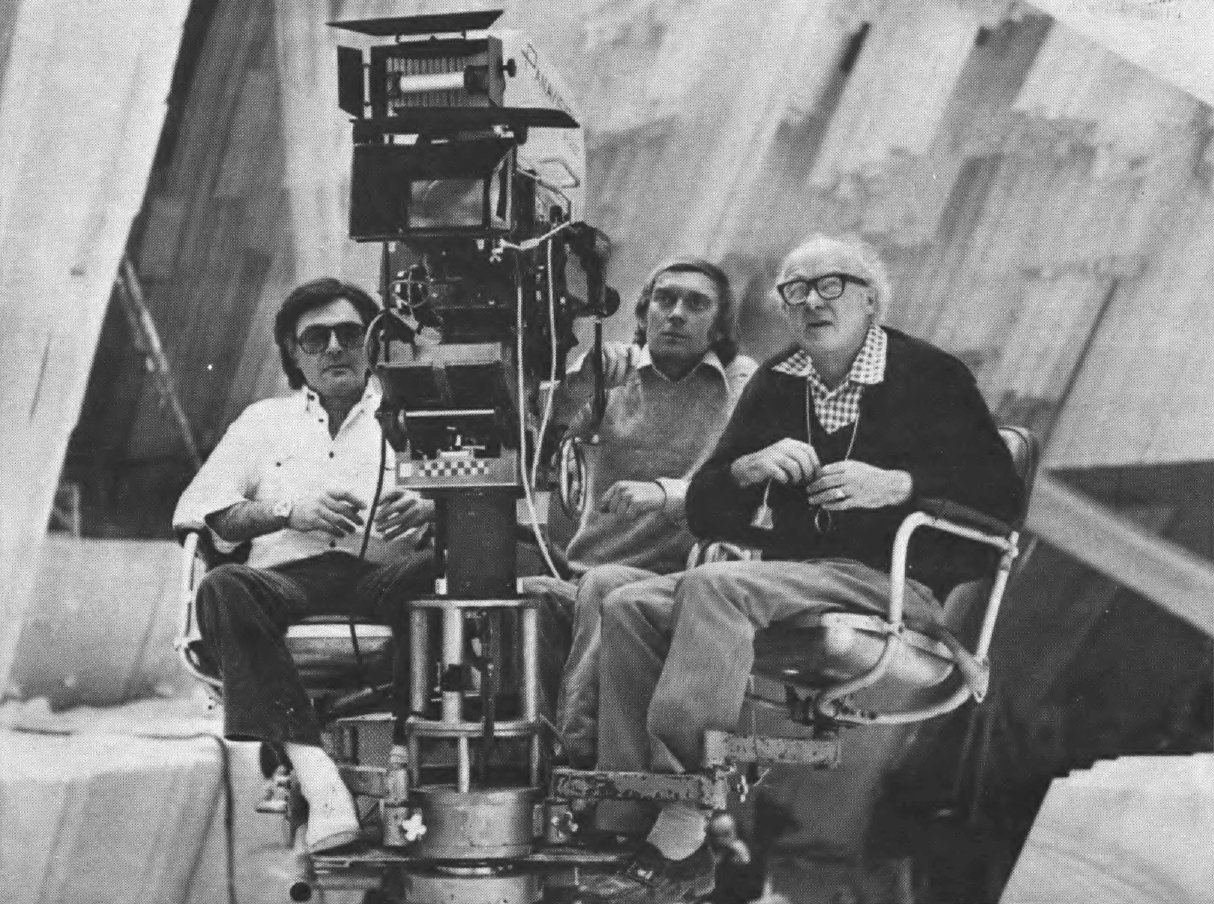

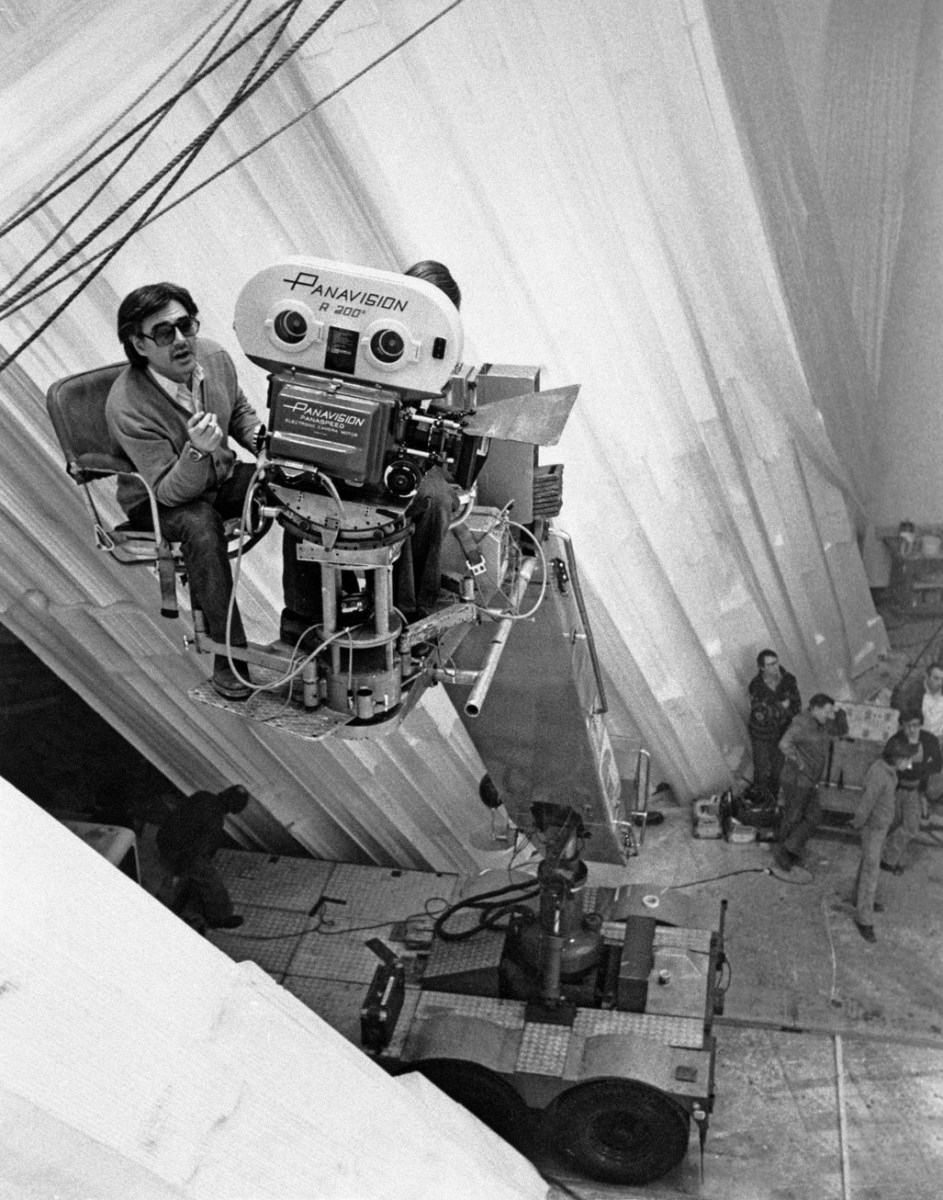

MacDonald (behind camera), process projection consultant Wally Veevers and Unsworth, shown on the set with front projection unit developed by Jan Jacobsen and Veevers. It’s a lightweight, mobile, easily transportable rig that

will fit on an ordinary dolly or crane.

He believed that an operator and a director should work very closely. He wasn’t a cameraman who believed that an operator should be there just to turn handles when told. He believed that an operator should take a very creative part in filming — for which I shall be eternally grateful to him. While you were getting the set-up, he would already, in his mind, be photographing the scene — so it was a very happy and, I thought, very successful working relationship we had together. The many directors I have talked to since his passing have all said the same thing — that they enjoyed the way we worked together. I certainly enjoyed it, and I just wish it could have carried on for many more years.

I realized the difference between the way an American cameraman and gaffer work together compared with the English system when we worked on location in New York. We had a superb gaffer, but he was obviously quite surprised when Geoffrey decided where every single light would go and exactly how it would set and look. I think this goes for every English cinematographer. They are more totally involved with the rigging and how the set is going to be laid out.

We had fantastic gaffers, such as Maurice Gillette, who did many of Geoff’s films and who, I am sure, could shade and pencil in exactly how a set should be lit, but not one light would be switched on until Geoffrey would come and say how it should be set. I think that is probably the basic difference between American cinematographers and European cinematographers.

Geoff Unsworth was, without a doubt, a consummate artist of the camera and, like many other Impressionists, he liked muted colors and a muted feel to a scene. He would be happier when the sun was in than when it was out, because he could have that lovely overall light, rather than the brilliant sunlight that leaves heavy shadows everywhere. That he loved a nice bright overcast day is evident in the scenes we shot for Superman in Canada, where we did the death of Superman’s adopted father, played by Glenn Ford in the film. It was a beautiful scene in a cemetery and we had one of those marvelous days when there was very little sun, but just a lovely, high, bright sky. The results look magnificent, with the lovely muted colors that made Geoff very happy.

Having been in many capitals of the world with Geoff, I recall that our Sundays were usually spent going through museums and art galleries in Madrid, Paris, or Venice or wherever we were working. We would go around and look at paintings, and certainly visit anything that was interesting in the town. We would never just sit in a hotel and read the papers; we would always want to visit the places of interest and, in so doing, see the pictures of the country.

“He was terrified (and these are Geoff’s words, not mine) every time he went onto a new set.”

only as an inspired artist of the camera, but as an extraordinary human being, much

beloved by his co-workers.

Geoff had a great feeling towards art and in his home, there are bookshelves full of books about painters and places. In every town we went to Geoff would buy a book about the place, even if it was only a village. I couldn’t believe that he could find books about all the places that he did. We went to someplace in Canada that wasn’t even on the map and he found in a local shop that there was actually a history of that little village. He bought it immediately and spent the evening reading it. He had a terrific interest in everything around him, and I think that, in many ways, that is what kept him very young in his ideas.

Geoff would stand in front of a painting and look at the lighting and study what the painter had done, but I think that any cameraman worth his salt would do the same thing. He would probably do it without thinking. When we were in Madrid we spent many Sundays going around the Prado and whereas I might look at many pictures and take them in, Geoff was much more patient and would study them much more closely than I did. He would sit for maybe half an hour and enjoy one picture.

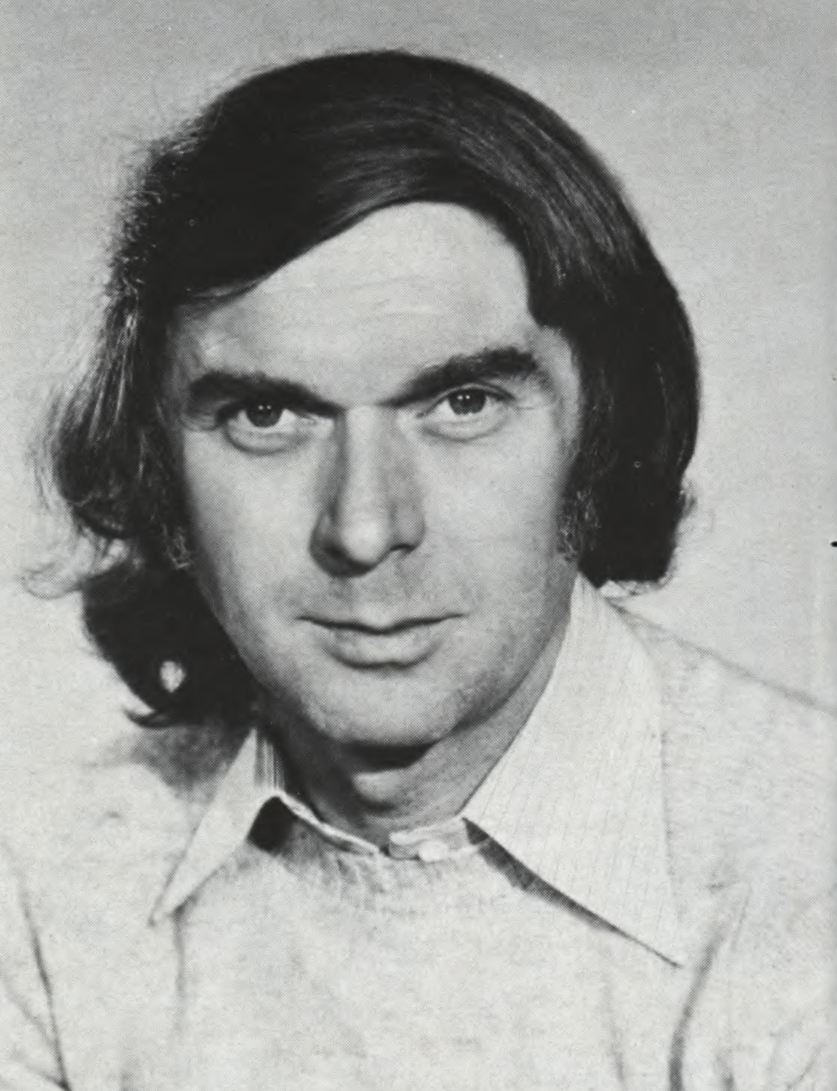

years working with Geoffrey Unsworth as

clapper-loader,

focus-puller and operator,

found it a very enjoyable experience,

which he wishes could have continued for many more years.

Geoff obviously had a great love for the cinema and went as much as possible. He admired many cameramen, but he had a special regard for Haskell Wexler. He had seen a lot of his recent work and felt that he really had hit a mood and style of photography that Geoff greatly admired.

In England, I could probably name 10 cinematographers whose work he was very fond of, but I will simply say that his regard for David Watkin was very high. He felt that David had tremendous courage in the way he photographed subjects and that he was very original. I know that when the two first met (I introduced them), they talked to each other as if they were long-lost brothers. They obviously both had admiration for each other and yet had never met because they came from totally different schools of photography. David had never been a cameraman during the big studio time, while Geoffrey had, but Geoff loved some of David’s work, especially the interiors for Charge of the Light Brigade, which he thought was one of the best photographed films he had ever seen. (And I must say I agreed with him.)

Geoff was especially proud of John Alcott, who had been his assistant for many years and later won an Academy Award for photographing Barry Lyndon.

Geoff was regarded by almost everyone who knew him as one of the all-time great cinematographers, but he never felt that way about himself. He was a very modest man. If anything, he was an overly-modest man. As far as his photography was concerned — and I’m sure this goes for most cameramen — he was terrified (and these are Geoff’s words, not mine) every time he went onto a new set. But once he had made up his mind how it was going to look, he was happy.

crane, line up a boom shot on the set of Superman. The opening sequences of the film,

which takes place on the planet Krypton, include heavy effect photography, but for the

Earth sequences, Donner preferred a more straightforward “comic book” style.

He himself said to me many times that every new set could become a nightmare. He knew how he wanted it to look, but he wasn’t always sure how that could be achieved. Geoff couldn’t pre-plan and pre-light the way that many cameramen can. It had to come to him at the time. But once he got the feeling of how it was going to look, then nothing could stop him, and very soon he would get the result he wanted.

Geoff loved photographing period pictures and I think he must have been very happy with the period of Tess, the picture he was working on when he died. He loved pictures like Beckett, into which he could put a mountain of mood. I think Geoff loved almost everything that he went into, but if you gave him a period film, if you gave him some candles, he was very happy — because then the cameraman could really use his art to the fullest.

He also took great pleasure in making any women who came in front of his camera look as beautiful as possible. However, this sometimes led to complications, because there were times during the course of a film when the director would not want the artist to look quite beautiful.

I can remember a time on Cabaret when the character played by Liza Minnelli was supposed to have had one hell of a night drinking and doing a few other things that I can’t go into in a magazine like American Cinematographer. Bob Fosse wanted Liza to look a bit rough the next morning and he had a terrible time with Geoff, trying to make Liza look not quite as beautiful as Geoff wanted her to look. I mean, Geoff saw every woman as someone who should look beautiful and would try harder than anyone else I’ve ever met to make them look that way.

There were many cameramen shooting in other units of Superman, as anyone will note who can stay to the end of the credits. Geoff was in contact with them, but never over-instructed them because, being the type of person he was, he never wanted to put too much pressure on anyone. But obviously, there were times when sequences had to be left by us, as a first unit and continued by a second unit. There were other times when Denys Coop’s unit, which was an entity on its own, continued happily photographing whole sequences.

Of the many cameramen who contributed to Superman, I must say a special word about Alex Thompson [BSC], with whom Geoffrey was very impressed because Alex matched Geoff's stuff to a T. I think any cameraman reading this article will realize that it’s harder to match somebody else’s work than to do original work. I know how impressed Geoffrey was with the way Alex matched his work, and he himself said to me that he felt that Alex very often improved it. I know that Geoff would have liked me to say that.

There are several other cameramen on the picture that I could talk about for hours, but Geoff did have a special affection for Alex because of the way he obviously tried so hard to match his work.

Since Geoff passed away before he could do so, I have been given the task of grading (or “timing,” as the Americans say) Superman. Geoff was always very involved in timing, as any cameraman obviously must be. It is no good spending months of your life getting things exactly as you want them only to leave the finishing to someone else, because the chances are that their ideas might be somewhat different than yours, or slightly less daring.

Over the years I’ve sat in with Geoff on many grading sessions, but this will be the first time — and I must say that I’m extremely worried about it — that I am going to take some responsibility for making decisions. I have, I know, people who will help me — like Les Ostenilli of Technicolor, as well as Denys Coop, who did some magnificent work on Superman and who had a unit of his own for the whole time. He has already started timing some of the reels and I will do the rest. I know how Geoff would have wanted it to look and everything that can be done will be done to make sure that Geoff’s work looks like Geoff’s work.

Geoff’s contribution to any and every film that he worked on was that everyone knew that the results would be as good as humanly possible. But apart from that, Geoff had a unique “presence” — and I wish I could think of a more precise word — but it was a presence on a set that used to give everyone around him confidence. I mean, if you look at a picture of Geoff — even if you haven’t worked with him — you can see that, and directors, actors and actresses always felt that they could go to Geoff and lean on him. Many of them did over the years, and many who read this article will spend a quiet moment remembering those times.

Since he has been gone, I have spoken to perhaps 15 directors we have worked with and all of them have swapped stories with me about: “Do you remember this?” or “Do you remember that?” But what all of them have talked about most was Geoff’s strength. Geoff was always there. He was always there first thing in the morning, and he was always there until the end of the day. He would never miss rushes. Anyone could phone his room, if you were on location, and have a chat.

Geoff had a presence that was there then — and, I think, will be with us for quite a long time.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Rarely has a man been more beloved by his co-workers in the world-wide filmmaking community than was Geoffrey Unsworth. He was a gentleman in the most literal sense of the term, and an inspired artist of the camera. He was also, although quite shy, a very warm, witty and compassionate human being. It is to the memory of this very special man and his rare combination of qualities that this issue of American Cinematograher is affectionately dedicated.

You'll find our complete interview with director Richard Donner here.

Alex Thompson, would go on to shoot such films as Legend, Labyrinth, Alien3, Cliffhanger and Demolition Man. He passed away in 2007.

Denys Coop passed away in 1981 after a distinguished career as a camera operator on films such as the 1949 noir classic The Third Man, The Guns of Navarone, Lolita, Of Human Bondage and Ryan’s Daughter. He also had 26 director of photography credits to his name, among them the cult-classic 10 Rillington Place.

Peter MacDonald would go on to join Thompson working on both Legend and Labyrinth, and was DoP for the second unit helicopter sequences in Rambo: First Blood Part II. He worked on Tim Burton's Batman film in 1989 and made his own directorial debut in 1988 with Rambo III. More recently, he has worked as a second-unit director on films including Guardians of the Galaxy, Wrath of the Titans and Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire.