Best Achievement In Cinematography: Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

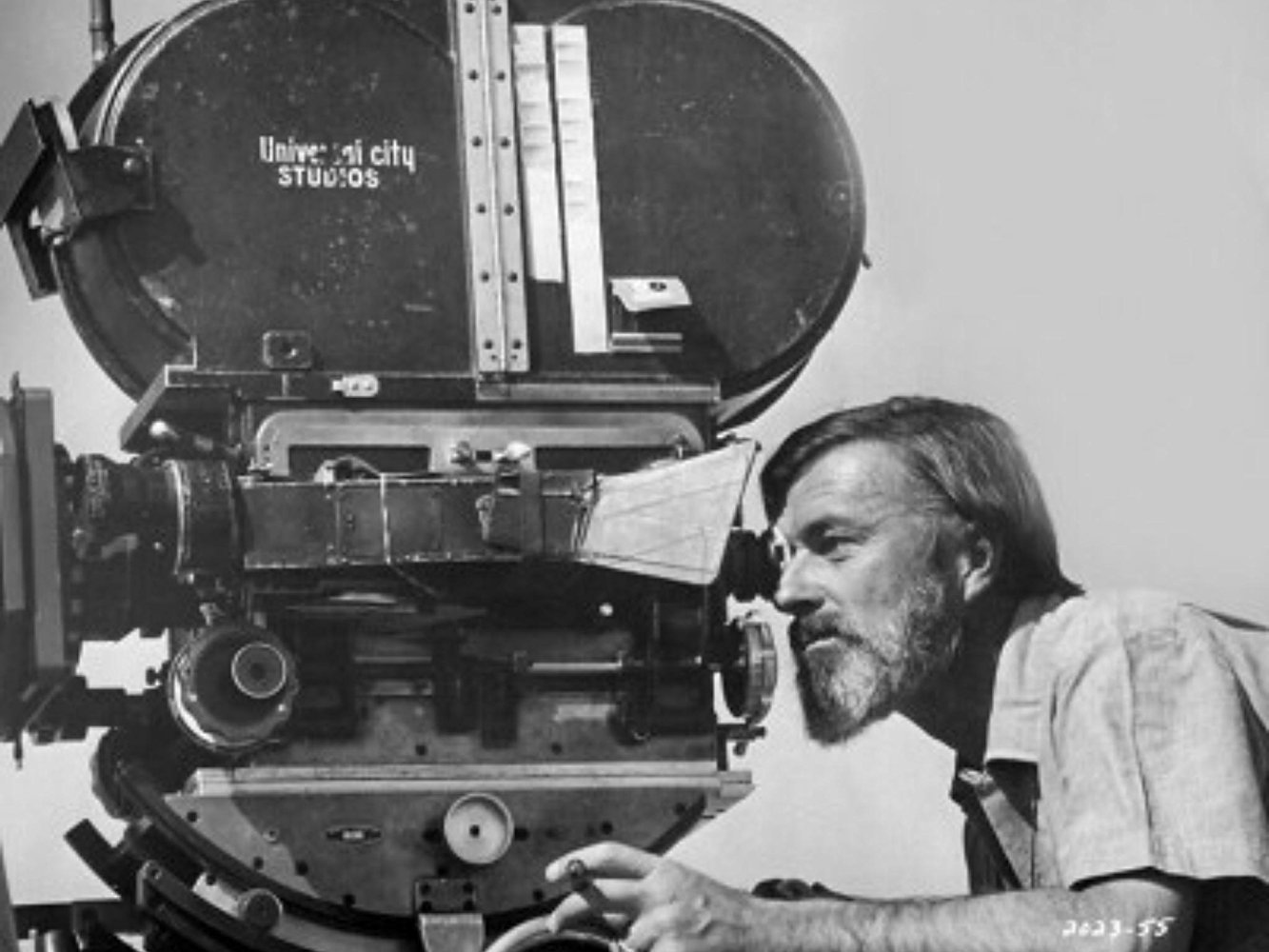

Conrad Hall, ASC, awarded coveted Oscar as top cinematographer of 1969, discusses challenges and techniques of photographing the winning film.

Rattling around in the unaccustomed spaciousness of a 747 Jumbo Jet en route across the Pacific, I was told that the in-flight movie to be shown was Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

I had already seen, and enjoyed, this very entertaining picture twice — but no matter. I have been known to view a really superior film (Citizen Kane, Seven Samurai) as many as a dozen times, so I was looking forward to another go-round with Butch Cassidy. It struck me, however, that it might be interesting this time to watch the picture without the sound, so that I might study the purely visual elements (photography and editing) of the production.

I settled back, free of earphones, and gave myself up to purely visual contemplation of the images that flowed across the screen. Undistracted by dialogue, music and sound effects, I was able, for the first time, to give full attention to the photography, and I was stunned to discover how absolutely right each separate scene was in terms of mood, composition, camera movement and lighting. The style varied from raw and gutsy to soft and dreamy as the shifting moods of the action demanded, but it was always exactly appropriate to the specific segment of the story being portrayed.

“There isn’t a single new technique in Butch Cassidy, as far as I’m concerned. It’s what I’ve done all my life. Technique varies with each story, and you draw on your experience to try to tell the story as best you can.”

— Conrad Hall, ASC

In my previous two viewings of the film, I had, of course, been aware that it was beautifully photographed, but the photography had not jumped out at me to call attention to itself. Now I realized that this was precisely why it was so very good. The director of photography had sublimated his personal ego in favor of dedication toward telling the story in the most provocative and appropriate way. He had done so with the highest degree of professional skill and artistry, but without once calling attention to himself or shouting, in essence, “Look what a jazzy cameraman I am!”

When the picture faded from the screen (somewhere in the neighborhood of Hawaii) I asked the stewardess for stationery and dashed off an impulsive in-flight letter to Conrad Hall, ASC, telling him what a really fine job I thought he had done in photographing Butch Cassidy. It was not, God forbid, a fan letter, but simply a note to an old friend, saying: “Well done, buddy!”

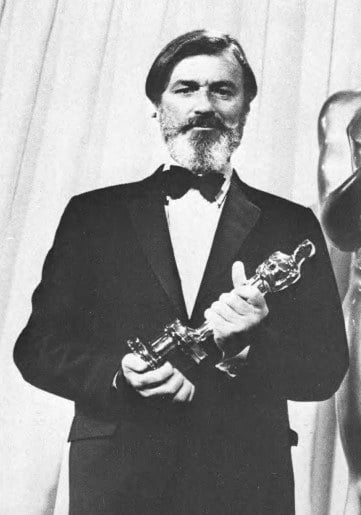

On the night of the Academy Awards I encountered him just as he was entering the auditorium with the radiant Katherine Ross on his arm. There were happy hellos and I wished him luck. I saw him again backstage immediately after he had won the coveted Oscar and I took a picture of him to capture the moment (see right). He was a lot more surprised that he had won than I was — and clearly on Cloud Nine.

Later in the week, at my request, he flew down to Hollywood from San Francisco to tell me about his part in filming Butch Cassidy. In discussing his basic approach toward the photography of the picture, he said:

"I met with the director, George Roy Hill, at the very beginning and we spent a lot of time talking about the script. The story is about two hold-up men who are put out of business by advancing technology — by "Superposses" and banks that have become invulnerable. They try other means of earning a living, but they find they are not suited for anything else — not even the army wants them. So they just keep on going downhill until the final denouement.

“The objective in the filming was to have this inexorable envelopment of modern technology come over as some sort of symbolic thing, so that the law and advancing technology would be evidenced as symbols, rather than actual, recognizable elements of society. We had to do something visually to get this idea across—yet, in terms of action, we still had to have the traditional chase between the desperadoes and the law.

“We talked a lot about it and finally came to the conclusion that the best thing to do was to keep from recognizing any of the members of the Superposse as individuals, to keep them always at a great distance, to keep them moving at a steady, relentless speed, rather than hellbent for election — but never stopped. They are always moving, always coming on, not hurrying, but always overtaking. The men they are chasing stop to rest, but they never rest. They just keep coming. They are, in a way, superhuman.

“I felt that the best way to show this in visual terms was to use an extremely long lens and take advantage of things like heat-wave distortion to make the figures wispy, unrecognizable, yet somehow menacing. I'm not certain that it works all the time, because when you use a long lens there is a tendency to make things very beautiful. The lens throws the background and the foreground out of focus and creates a lovely, dreamy sort of aura that kind of works against anything you show being a menace.

“However, in this case, because the men of the Superposse are all dressed alike, because they are always far away and always keep coming, I feel that they actually become a menace. I tried to enhance this impression photographically by keeping them at a distance, enveloping them with dust, distorting them with heat waves and shooting them through out-of-focus leaves and such, in order to have them come over as symbolic rather than real beings.”

The lens he used to achieve these effects was Panavision’s 50mm-to-500mm Panazoom, racked out all the way.

“I had the attachments to extend the focal length to 1,000mm,” Hall comments, “but I didn’t feel the need for all those extra millimeters.”

While Hall’s use of the long-focal-length lens just described is not new (and he would be the last to imply that it is), there is one radical technique which he utilized in Butch Cassidy that might be considered unique — and even quite dangerous in the hands of anyone but a master technician.

In short, he had deliberately overexposed some of his exterior scenes by two full stops in order to wash some of the “postcard Blue” out of the sky.

“I had become obsessed with the cliche of the blue sky,” he explained. “They look too pretty-especially in a film that’s supposed to be very dramatic. Naturally, when you’re shooting out on the desert or up in the mountains you’ve got a lot of blue sky. I tried my best to get rid of this by overexposing the film radically and forcing the laboratory to print it back. This pales out the blue to something soft and light, and I could stomach that. Also, it's easier and faster to work this way because you don't need any booster lights when you over-expose the film. There's no need to fill the shadows because you've already exposed far beyond what the normal exposure for shadows would be.”

My mind boggled.

“But what happens to peoples’ faces?” I asked, somewhat aghast. “When you’re that far overexposed you not only wash the color out of the flesh tones, but you lose the texture, as well.”

“Well, I don’t mind washing out the texture,” he said. "I hate everything razor sharp. On Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here, I used the overexposure technique almost all the way through the picture and the footage looks beautiful."

What could I say? He had just won an Academy Oscar by doing what made my blood run cold just to contemplate.

He went on to elaborate on the sharpness thing.

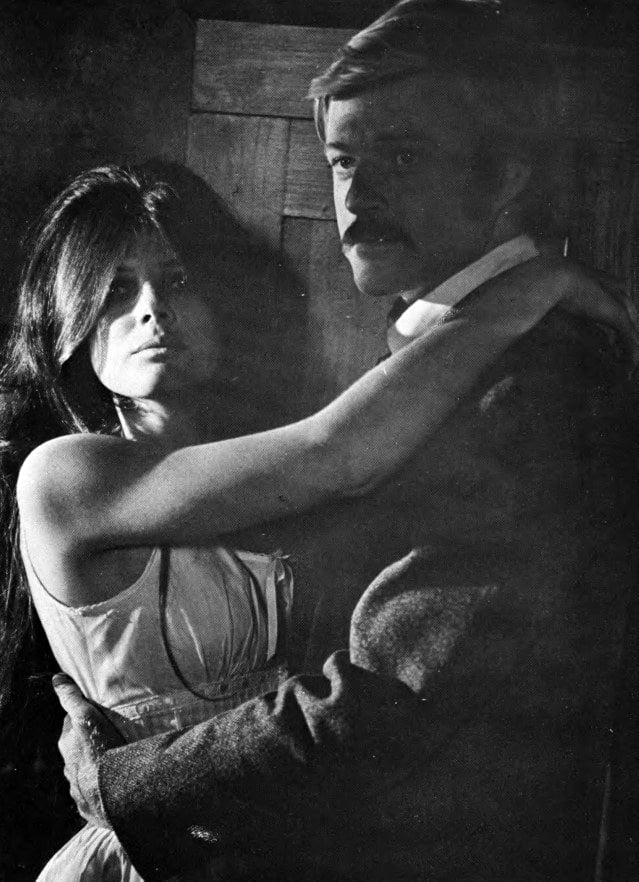

turned genteel gun-moll, strolls with Hall on location

in St. George, Utah. Other locations included Durango and Silverton,

Colorado and Taxco and Cuernavaca in Mexico.

“I’m an ‘against-sharpness’ cameraman, for the most part,” he said. “I dislike sharpness in the foreground and sharpness all the way to infinity. I used to love it at one time in my development as a cameraman — during my Citizen Kane phase. I used to stop down to F/64, and that sort of thing. But I’ve changed, and I don’t like that look any more. That doesn’t mean that it’s not valid, or that I might not use it if it worked for a story I was telling — which is the only criterion as to whether anything is valid or not anyway. But, generally speaking, I prefer to place the focus on that part of the story that is important and leave the part of the story that is not important out of focus. Therefore, I like to focus on the people — and I like to change focus back and forth, if it can be done smoothly without calling attention to what is happening. This can help tell your story, because it directs audience attention to whatever it is you’re focused upon. This is not new or anything; it’s just the way I like to do it now.”

I asked him about his approach to the lighting of interiors on the picture and he said: “I tried not to put too much light on inside. I don’t know if I always succeeded, but there were several scenes I liked. I wish I could do a picture in which I liked all of my work, but that hasn’t happened yet and I’m not sure that it ever will. Anyway, there was this one scene that is supposed to take place in a police station in Bolivia. Someone comes in from outside and talks to the people and then they all rush out. There was an F/12 light outside and a level of F/4.5 inside — way out of balance, but that’s the way I feel it should be. I was using a Fay light with spun-glass diffusion for fill, and I started out with all five lamps burning. One by one, I turned all of them off. Then I chickened out and turned one of them back on to shoot the scene. It looked fine, but it might have looked better with no fill at all.

“Someday, Eastman will make a film that is as fast as the human eye, and then there won’t be any actual lighting involved. You’ll simply be concerned with the story and the telling of it from your point of view. I can hardly wait for that day.” — Conrad Hall, ASC

“I have a tendency to put too much light on things, and I’m trying to combat that. What I want to do is make the film work instead of me. I’d like to be able to open up the lens to expose for what it is I want to see, and damned with what I don't want to see.

When you’ve known Conrad Hall for any length of time, one of the things that impresses you most about him is his complete honesty. He is, in particular, brutally honest about himself and his work, so I was not especially surprised to hear him say:

it." He is the most severe critic of his own work.

“I hate my night-for-night street scenes in Butch Cassidy because there's too much light on them. They’re lit up like a studio lot. You tend to do that when you’re working for a major studio and they load you up with so much lighting equipment — especially when it’s cold. People start turning on lights and you go over and start turning them off. But it’s easy to get confused about your concept and end up settling for less than what you really want. That’s something every cameraman is faced with. You don’t realize at the time that you're doing wrong, even when you view the dailies. It’s later, when the film’s all put together and you see that street all lit up like a Christmas tree that you realize you could have done better. All you can do is try to never let it happen again — or try never to be cold when you’re lighting, or settle for less than what you really think is the best.”

I mentioned the famed bicycle sequence in the film, that light-hearted romp on two wheels which is a sequence that seems to stick with the audience.

“That sequence was simply having fun with the camera, as far as I was concerned,” he commented. “But, in terms of mechanics it means talking somebody into shooting it at the right time of day... shooting just as the sun is going down, with the long shadows reaching out... being able to move around to locations you’ve picked for certain effects — like finding a fence with the slats out, and waiting for the sun to kick into the lens to create a marvelous visual effect. You have to send everyone home except the principals and work with a very small crew in a jeep so that you can move around. You don’t tell anybody what to do. You just turn them loose in a field and tell them to have fun with the bicycle and chase cows, or something like that. But it's not all as haphazard as it sounds. You’ve got to have a very good operator and an assistant who's really sharp with the follow-focus, plus someone to use judgment with the zoom lens...when to go in...when to pull back. You should usually have two cameras going on a thing like that. It’s the spontaneity that’s important. That whole thing was shot with the zoom racked out to telephoto length, using heavy fog filters. We used #3 fog filters on that sequence and #2 on most of the other exteriors. Again, it was a matter of destroying the sharpness of the image.”

I reminded him that his striking photography of Hell in the Pacific (the world’s worst title!) was razor sharp almost all the way through.

“I didn’t use any fog filters on that,” he admitted, “but for a different reason. I didn’t feel that the story warranted any beautification.”

aura of romance in love scenes involving Ross and Redford. Such sequences, interspersed with violent action, lend the film a dimension of light and shade that boosts it far above the level of the usual Western. He could sense the question that was running through my mind.

“No,” he said, “you certainly couldn’t call Butch Cassidy a beautiful story — but it was, essentially, a comedy. It read like one. The script was full of hilarious one-liners, and that’s the way George Roy Hill seemed to want to stage it. He wanted it to be clever and still have a sense of history about it. You could have done the picture in an entirely different way, made it a serious film about the phasing out of banditry, just as they did in The Wild Bunch. But the director chose not to do it that way, so I selected a style of photography that would enhance the fun of the piece and give him what he wanted.”

I commented upon the effectiveness of starting the film in sepia and then very subtly dissolving to full color in the midst of a panoramic long shot.

“That was planned precisely in the script, either by the writer or the director—I don’t know which,” said Hall, “but the shot in which the change takes place is something George sent me out to shoot by myself. I went out with a small crew at about 5 o’clock in the morning and shot the scene in the pre-light of dawn. It was a shot in which the sun comes up and hits them as they’re riding toward the mountains. I knew that the color would not have to be toyed with, since it would look like sepia because the rays of the sun are almost that color at that time of morning. The sepia sort of melted into gold as we panned around to blue mountains in the background for a marvelous transition.”

Since Butch Cassidy is something of a period piece and many of the scenes have kerosene lamps as an apparent source, I asked him about his method of getting this effect to look realistic on the screen.

”A typical example is the sequence after the chase in which Redford and Newman are having dinner and Katherine is serving them,” he said. “There are two practical kerosene lamps in the scene and we have to presume that the light is actually coming from them. Since we’re shooting in color we can’t get enough exposurable light from the actual flame to photograph the scene, so my approach is to hide a small peanut-type lamp [sometimes called a “gimmick”] behind the flame itself. Then they take it down on the dimmer to a point where the drop in voltage will lower the color temperature to a yellowish cast nearer to the color of lamplight. Now, this creates a very hot-looking flame — much hotter than it would appear in a real situation, but it does give the illusion of the flame actually lighting the scene

“The other alternative is to beam a light down onto the lamp itself to sort of brighten it. This never looks to me quite as real as the first method, because it's not hot enough to cast that much light onto the actor’s face. Neither one of them is really satisfactory to me, but they are the two ways that are used most often. Of course, there will come a time when we won't have to worry about creating such effects to make them look real. Someday, Eastman will make a film that is as fast as the human eye, and then there won't be any actual lighting involved. You’ll simply be concerned with the story and the telling of it from your point of view. I can hardly wait for that day.”

He had a mischievous gleam in his eye, and he might have been putting me on.

But then, again — he might have meant it...

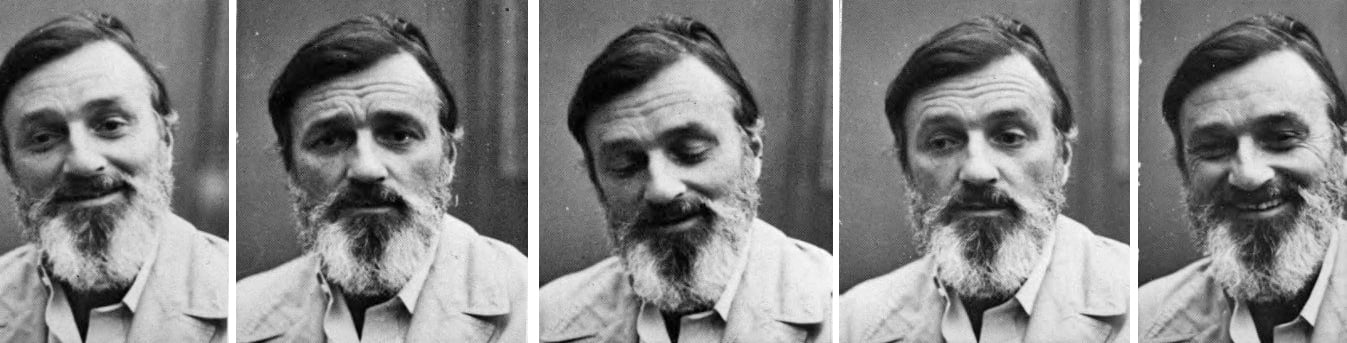

author. A thorough professional, highly trained in the classic tenets of cinematography, he now dares to break the rules in reaching out for more honest

and interesting ways of telling a story on film. In seeming contradiction, he says: “There isn’t a single new technique in Butch Cassidy, as far as I’m

concerned. It’s what I’ve done all my life. Technique varies with each story, and you draw on your experience to try to tell the story as best you can.”

Hall is a graduate of the University of Southern California Cinema Dept., where he studied under the great Russian montage expert, Slavko Vorkapich. After graduation, together with two former classmates, he formed Canyon Films and became a cameraman “by accident” when they drew straws to see who would do the photography on their first color feature, My Brother Down There, which was made in 18 days on a $150,000 budget. Later he photographed footage for several Walt Disney nature films including: The Living Desert and Islands of the Sea.

He eventually became camera operator for such ASC members as as Robert Surtees, Ted McCord, Ernest Haller, Floyd Crosby, and Hal Mohr. His first assignment as director of photography was on the TV series Stoney Burke, followed by The Outer Limits.

Hall’s feature credits include The Wild Seed, Incubus, Morituri, Harper, The Professionals, Divorce American Style and Cool Hand Luke.

He received a 1965 Academy Award nomination for his black and white cinematography of Morituri and was nominated again in 1967 for his stunningly dramatic photography on Richard Brooks' filmization of the Truman Capote best-seller, In Cold Blood, which was shot entirely on location in Kansas and in the other locales where the grisly events actually took place. Since then he has functioned as director of photography on Hell in the Pacific, The Happy Ending and Tell Them Willie Boy Was Here.

He is currently preparing to direct his first feature film, from his own screenplay based on a William Faulkner novel.

Editor’s note: Unfortunately, Hall’s feature directorial debut never came to pass. Learn much more about the cinematographer here.