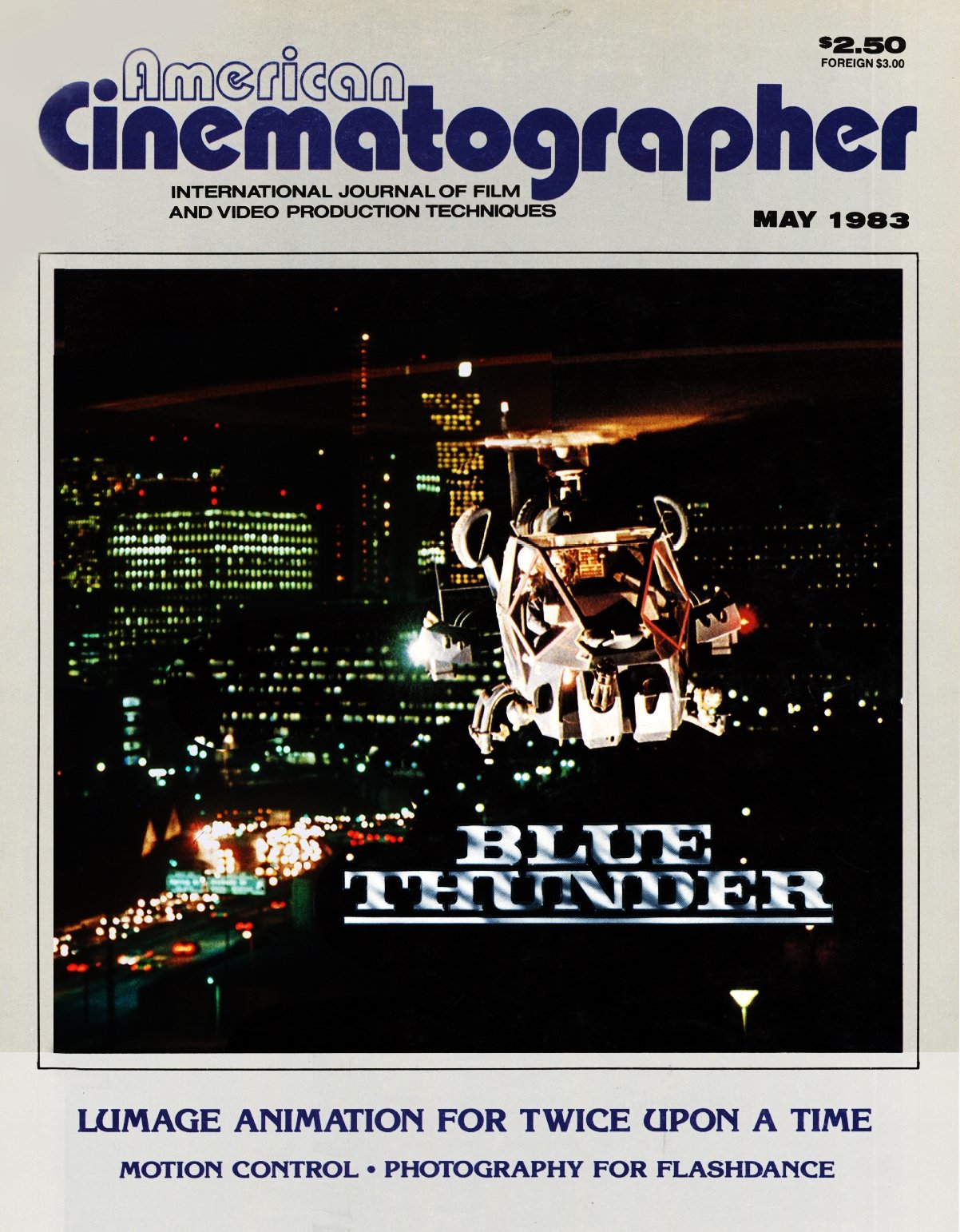

Blue Thunder: Helicopters, Process Photography and Explosions!

“It’s one of the few pictures I have seen associated with where the images on the screen are better than what I envisioned when I read the script. Everything worked, and then some.”

The script for Blue Thunder posed a series of unique production problems not the least of which was the fact that its setting and story demanded a high degree of realism while at the same time requiring substantial portions of the film be shot with rear projection. It also called for such things as Sidewinder missiles destroying buildings in downtown Los Angeles, and helicopters crashing into bridges or construction sites, plus about 60% of the film takes place at night.

For many people the idea of rear projection conjures up hokey images of glamorously lit stars walking a treadmill in front of a background which has little or nothing in common with the foreground photographically. Nothing could be further from the case in Blue Thunder where it is impossible for a viewer to distinguish between the process shots and the aerial shots. The integration of studio rear projection footage into the aerial sequences surely represents some of the most effective use of the rear projection process ever achieved. The fact that so much of it was in night scenes worked both for it and against it. It made it much more difficult to shoot the background plates, as cinematographer John Alonzo, ASC, discusses in this interview; but at the same time a night background minimizes the problems of matching lighting and contrast between foreground and background.

For those who want to go back and try to figure out which shots in the film are process shots, we can offer the following clues:

• Roy Scheider is not really a helicopter pilot, but...

• It is possible to fly a helicopter from either seat in the cockpit.

• Daniel Stern, who plays Scheider’s partner, Lymangood, is also not a helicopter pilot and...

• The video monitors and electronic instruments in the cockpit of the helicopter had to be operated or fed via cables attached to equipment which was not mounted in the helicopter. From this we can deduce that whenever one sees both Scheider and Stern in the cockpit in the same shot, or whenever one sees the monitors or instruments in the cockpit the shot was done on the stage, and any backgrounds beyond the cockpit are rear projection images. Just for the record, Warren Oates’ office was not located next to a heliport either, so any action going on outside the windows of the office are rear-projection images.

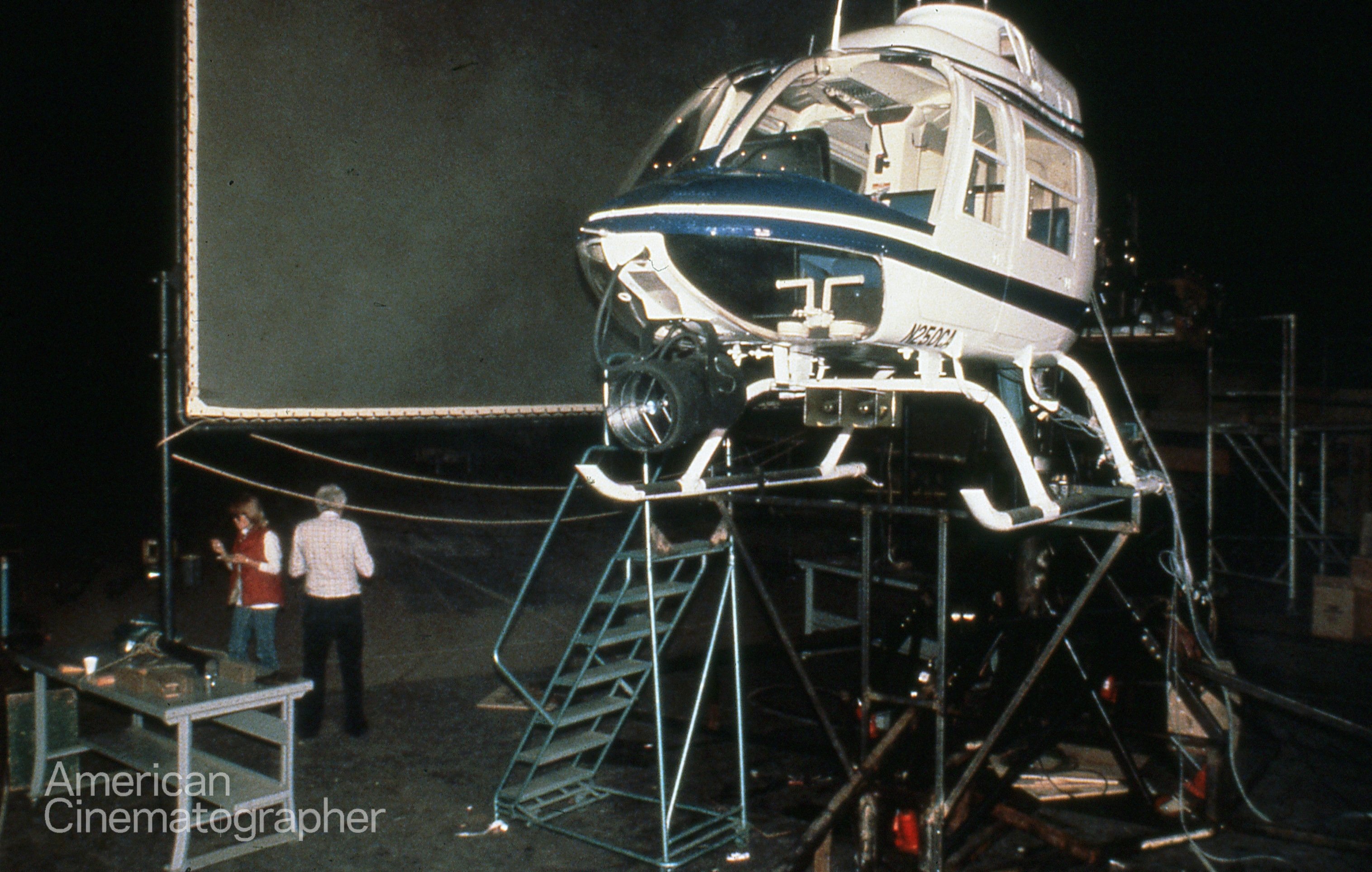

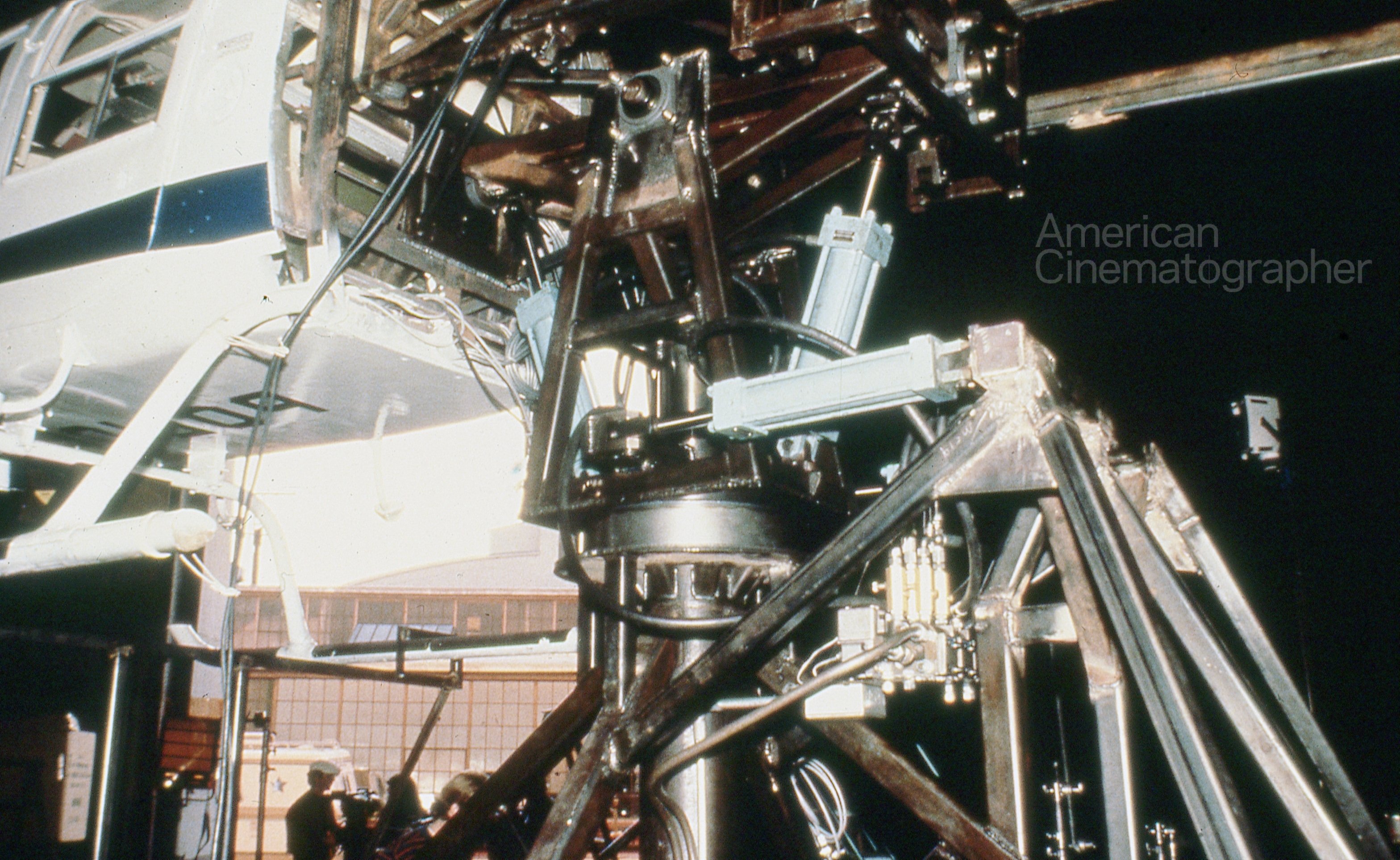

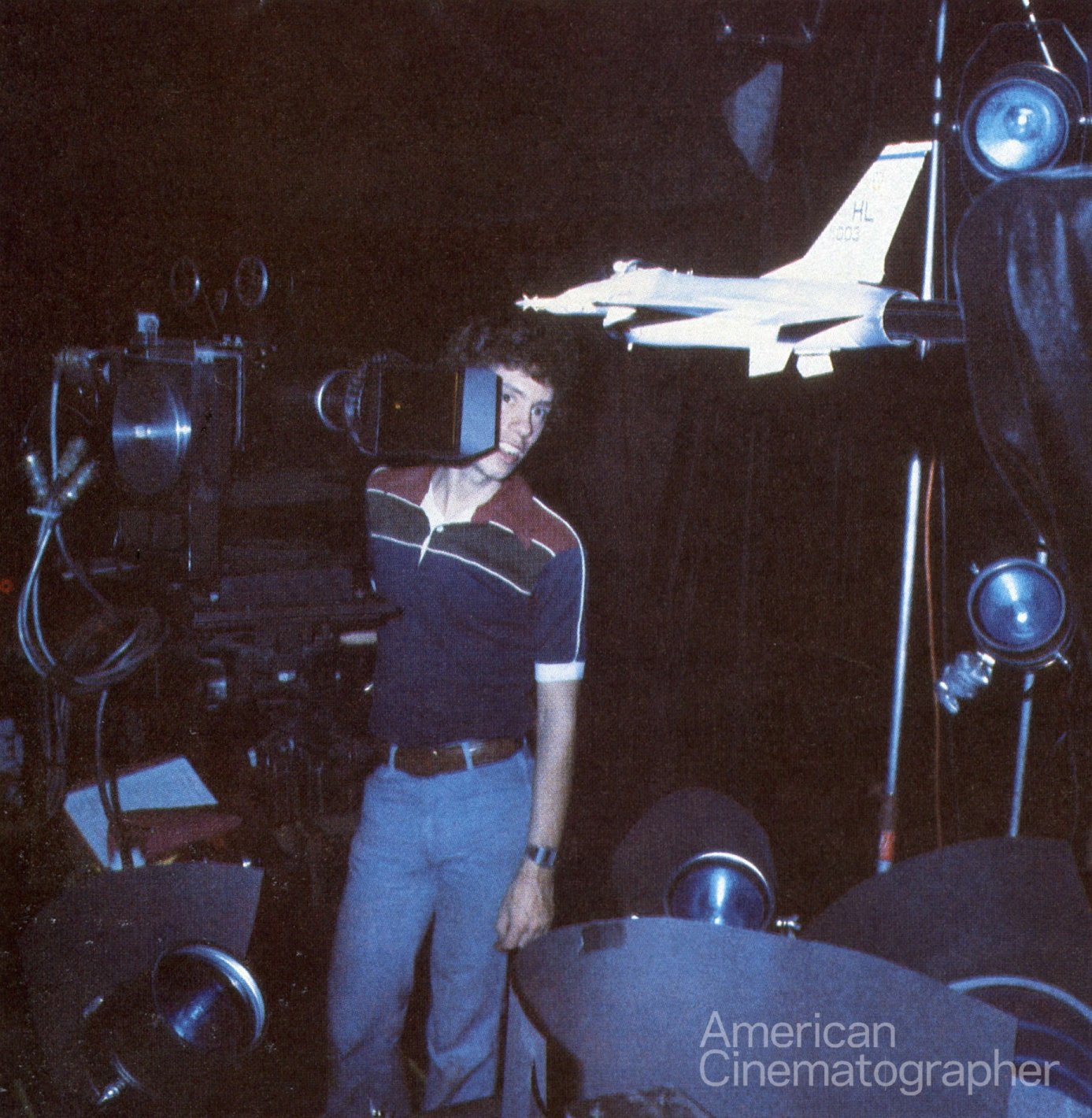

Aside from the night-for-night VistaVision background footage, which Alonzo discusses, there were three other things done to heighten the realism of the process shots. First, the mock-up of the helicopter cockpit was mounted on gimbals so that it could tilt, roll and yaw exactly like a helicopter in flight. A device was built with a plate onto which the mock-up for either the Blue Thunder special or the Jet Ranger helicopter could be mounted, and its movement was controlled hydraulically. Secondly, the camera itself was on a mount which enabled it to float in relation to the helicopter and the background in order to simulate the look of an aerial shot from another helicopter. Finally a second set of background shots was projected into a mirror and reflected onto the front of the helicopter to create the effect of reflections in the helicopter windshields. Tests with moving lights on the set failed to yield credible enough results so filmed images were projected onto the helicopter.

Perhaps the most crucial problem posed by the script was that of designing and building the Blue Thunder helicopter itself. While it is possible to produce a science-fiction film without spacecraft which can really fly (even Firefox was shot without an actual jet fighter), there was no way that Blue Thunder could have been convincingly shot without a real helicopter for the title role. It need not be capable of doing everything it appears to be doing in the film, but it did need to look as though it could.

The helicopter eventually cast in the role after extensive research was a 1973 French five-seat executive helicopter called the Aerospatiale Gazelle. It has a 592 HP engine which can run up to 43,500 RPM and it can fly at speeds up to 200 miles per hour. Among the distinctive features which helped it win the part is its turbine style tail rotor with a shark-like fin. It was felt that the tail configuration helped make the helicopter look both exotic and menacing. The cockpit, however, was completely redesigned to have flat windows and the simulated surveillance gear, weapons and armor plating were added to the exterior. The net result was that the craft was a bit nose heavy and could only fly about 100 mph. It also meant that only 70 gallons of fuel could be put in the tank rather than the normal 130 gallons, but the ship still flew well enough to be perfectly convincing in its role — thanks to Jim Gavin and his crew of pilots.

The gun on the front of the helicopter, which is supposed to be a 20mm cannon capable of firing 4,000 rounds per minute, was simply a set of wooden dowels on the real version of the helicopter. Even though this particular mock-up of the gun was not capable of firing it was capable of turning and was hydraulically controlled. The gun seen firing in the film is another mock-up which was not mounted on the helicopter and which consisted of metal tubing with spark plugs to ignite acetylene as it was blown through the barrels. The biggest problem was getting the barrels to rotate fast enough and insuring that each barrel fired when it was in the proper position. Hughes Aircraft had apparently offered to supply the production company with a real 20mm cannon, but at no time was a real weapon used for the filming.

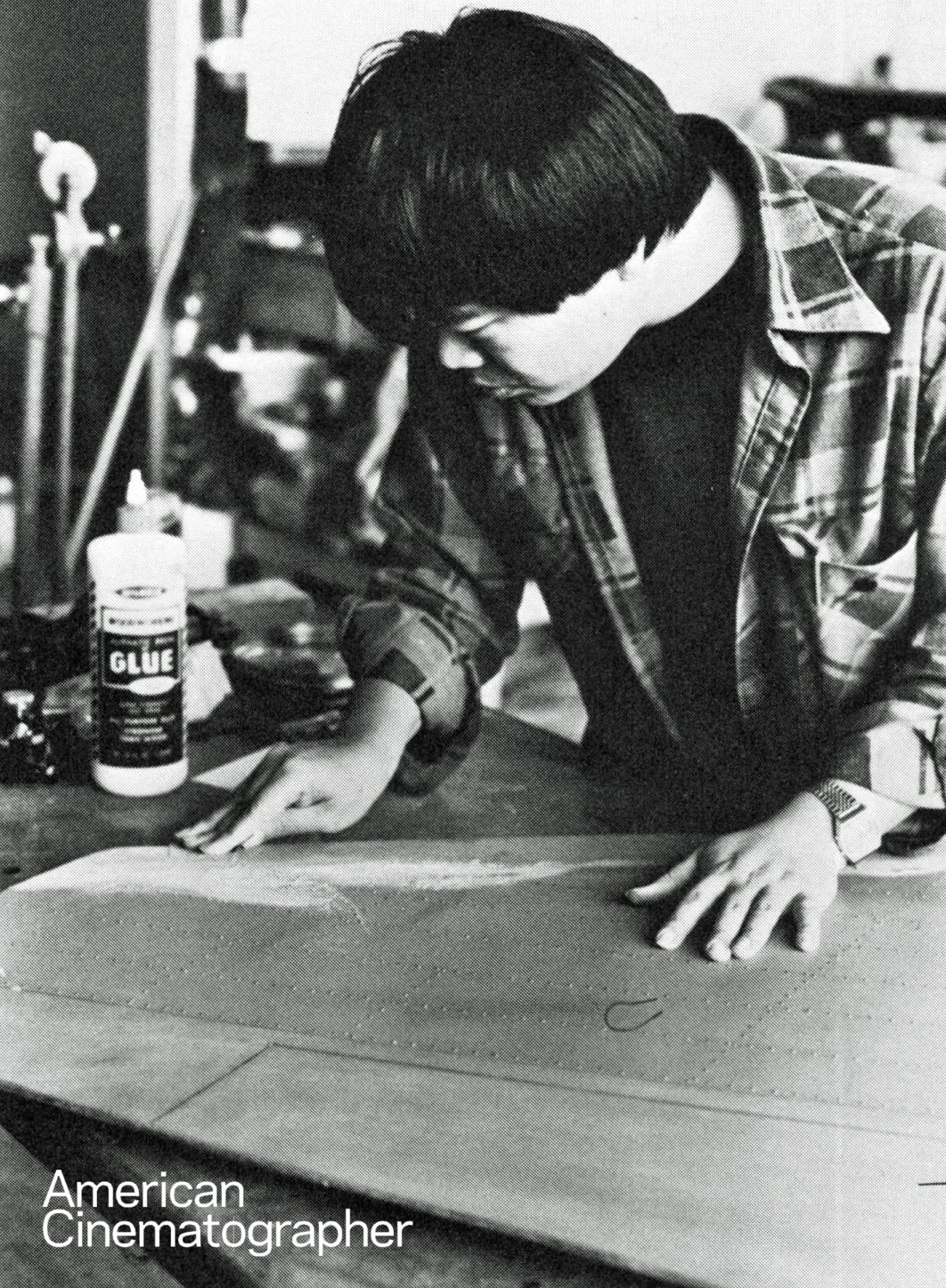

Most of the aerial sequences involving the Blue Thunder were filmed with the actual helicopter, but the shot of the Sidewinder missile hitting the Arco Tower as the helicopter flies away safely was done using a radio controlled version. The 1/10th scale used for the miniature buildings was determined by the minimum size possible for a realistic radio controlled flying model of the helicopter. It might have been even more convincing if the scale could have been larger (a 1/6th scale was considered), but the buildings had to be 75 feet tall as it was. The basic frame for the buildings consisted of 85 foot telephone poles sunk 10 feet into the ground. Tubular frames were added and most of the facade of the building was constructed of Masonite except for the areas to be blown up by the missile. Areas which were to blow up were constructed of a very hard, plaster like substance which was colored and molded into very thin layers which were glued onto the frames. The explosion was created by using some 1,200 “bullet hits,’’ the tiny charges planted in sets to create the effect of the bullet hitting a surface. The bullet hits were built into the structure by placing them in channels which could act as a mortar causing everything to blow straight out rather than in every direction. The charges were also wired to go off at slightly different intervals so that the explosion as recorded by the high speed cameras would appear to be happening in stages — even though to the naked eye it appears as one bang. In addition doll furniture and assorted miniature props were placed inside the building and blown out by an air mortar to fill the air with debris. A test was filmed using one section of wall, but when the time came for the real shot there could only be one take. Needless to say it was filmed by several cameras at various speeds.

For the sequence when the other missile hits the barbecue chicken joint, it was assumed originally that miniatures would be used as well. Later however an abandoned building was discovered in a section of downtown Los Angeles which made it feasible to do the explosion full scale. Art director Sydney Litwack designed signs and ducting and a chimney to go on the roof of the building and they were constructed by Chuck Gaspar’s special effects team so that they would blow apart in exactly the right places. A van parked in front of the building was made to fly up into the air by installing a mortar in it that shot a section of telephone pole down into the ground and kicked the van up into the air. Stunt extras were positioned on the street for background action and the explosion was timed to occur as the real helicopter pulled away from the building. For the final touch, hundreds of real barbecued chickens were dumped onto the scene with the result that sand had to be spread onto the street after everything was cleaned up in order to counteract the residue of grease left by the chickens.

In the end our hero spares the world further harassment by landing the Blue Thunder in front of a speeding freight train and piling out just in time to watch it be smashed to smithereens. Needless to say this was also a one take affair, but the operational version of the helicopter was not used. Instead a special mock-up was constructed out of PVC (polyvinychloride, a plastic which comes in sheets and tubes), Styrofoam and thin aluminum sheets. There was some concern that if the helicopter were too sturdy, it might cause the freight train to derail — even though it was moving slowly and being sped up by undercranking the camera. The helicopter also had to be fragile enough to squash when the locomotive hit it. It was rigged to explode apart at predetermined places and burn. The train had no problem with it and even carried the burning pieces about a quarter of a mile down the tracks. Before the explosion a series of shots were staged with the real helicopter landing on the tracks in front of the train and then the explosion was filmed by several cameras with the mock-up sitting on the tracks.

The Blue Thunder, of course, was not the only helicopter to bite the dust in the course of the film, and four crashable mock-ups of Jet Ranger helicopters were also built. One was for a scene in which the heroes are forced to crash land in a construction site because the villain tampered with the innards of their copter before take-off. Scheider manages to land on top of a shed and the helicopter crashes through the roof, turning over on its side inside the building. To accomplish this the roof of the shed was reinforced so that a real helicopter could land on it without totally squashing the building. After two days of landing on the roof, they finally got the right effect and a mock-up of the helicopter was dropped onto the roof of the shed which had now been rigged to collapse on cue. Finally the mock-up was mounted on a turntable inside the shed so that it could be turned around to wreak havoc inside what was left of the building. The mock-ups used for these shots were constructed of fiberglass on an aluminum frame with a chain saw motor driving the rotor blades. The second Jet Ranger to crash is one piloted by another policeman who is chasing the hero and crashes into a concrete bridge spanning the Los Angeles river. The execution of this shot was facilitated by the fact that like most everything else in Los Angeles, the bed of the river is paved and at most times of the year it is dry. For the final shot of the crash a track was built on the bed of the river which was used to catapult a mock-up of the helicopter into the bridge. A power winch and a pulley system was used to launch the mock-up off the track.

In addition to buildings and helicopters, a healthy number of automobiles were destroyed for the movie. Undoubtedly the most spectacular of these events was the police car which gets shot in half by the 20mm cannon on the Blue Thunder. The back end of the car separates completely from the front end and the front end continues to drive down the road kicking up sparks as it drives across the pavement. To accomplish this it was necessary first of all to replace the motor of the police car with a front-wheel-drive system from a K car. Then the car was cut in half and put back together with exploding bolts in a tubular framework. A spark machine was added to the rear of the front half of the car so that when the back half was blown away the driver could continue to drive down the street more or less in control of the car and kicking up sparks as he went.

In addition to this, about 22 cars were blown to bits during a demonstration of the fire power of Blue Thunder at a gunnery range. In order to insure that these cars looked as though they were blown up by the ammunition from the cannon rather than a single explosion from within, they were each cut into about 10 pieces and then put back together like a puzzle. Boards screwed on the back side of the cuts were blown apart on cue and a charge was planted underneath the car to make it jump into the air when it was hit. Needless to say, extreme caution was exercised in planning these explosions to insure that the helicopter flying overhead was not endangered.

Demolition work, while it may be the most eye-catching aspect of the production, is not what will make Blue Thunder a successful movie, if it is as big a hit as everyone associated with it feels it is going to be, it will be because of the overall design of he film and the degree of finesse with which all aspects of the production were executed. Shel Shrager, executive vice-president and executive production manager at Columbia Pictures says of Blue Thunder, “It’s one of the few pictures I have seen associated with where the images on the screen are better than what I envisioned when I read the script. Everything worked, and then some.”

From the initial conception of he movie as “dark” both philosophically and visually through to set design and lighting to the relentless pacing of the editing, the film represents a completely integrated team effort guided by a determination to ground an action-fantasy worthy of he far reaches of the galaxy in a setting as believable as the 11:00 news."

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.