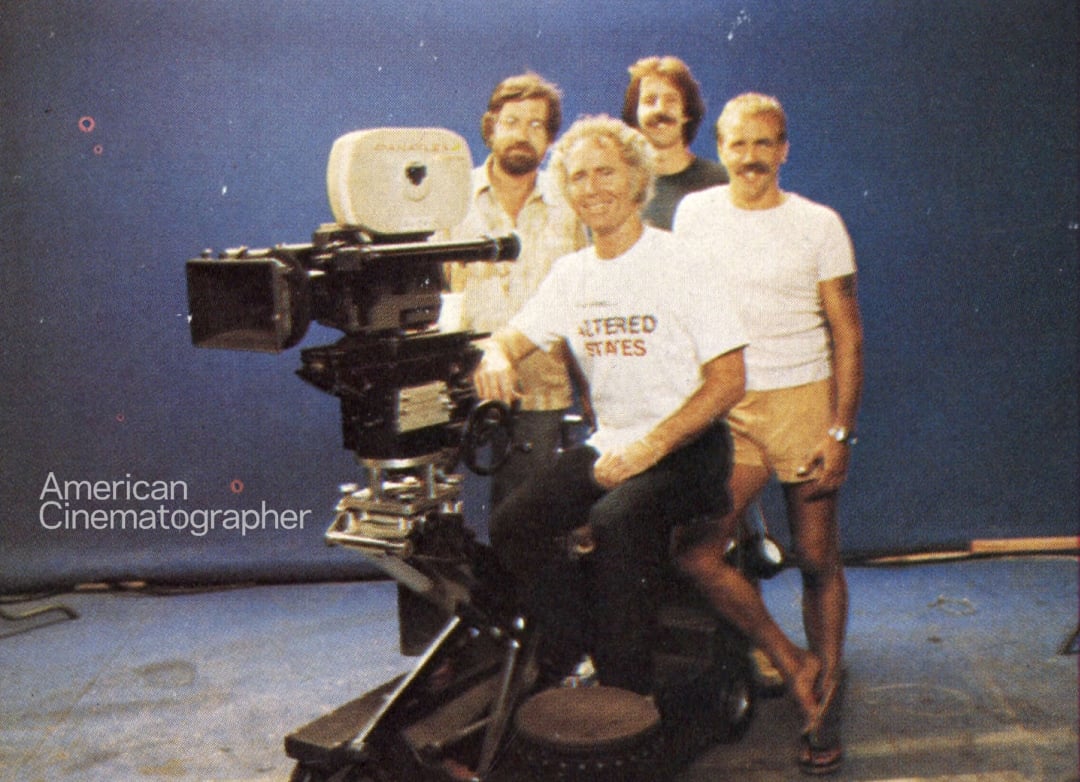

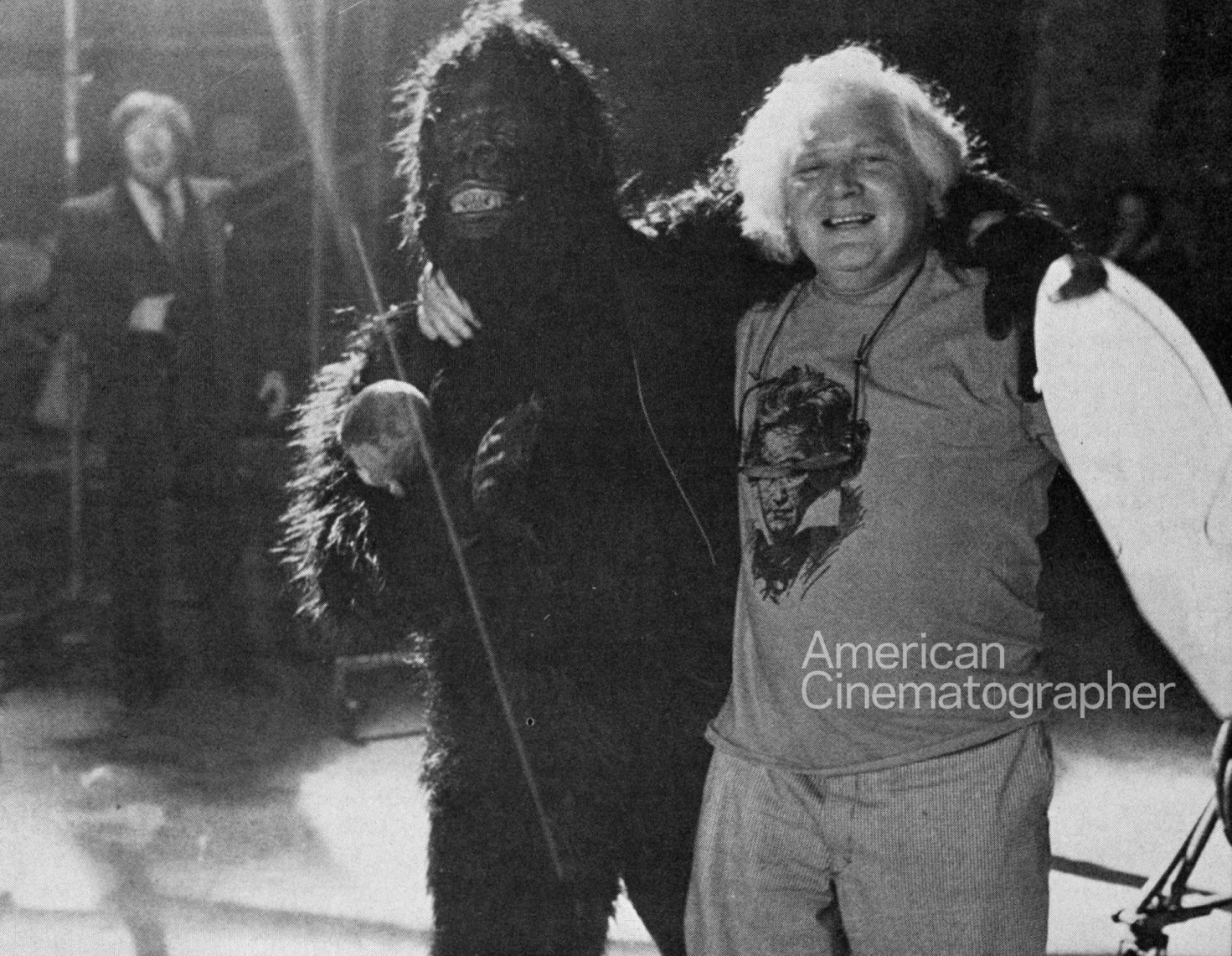

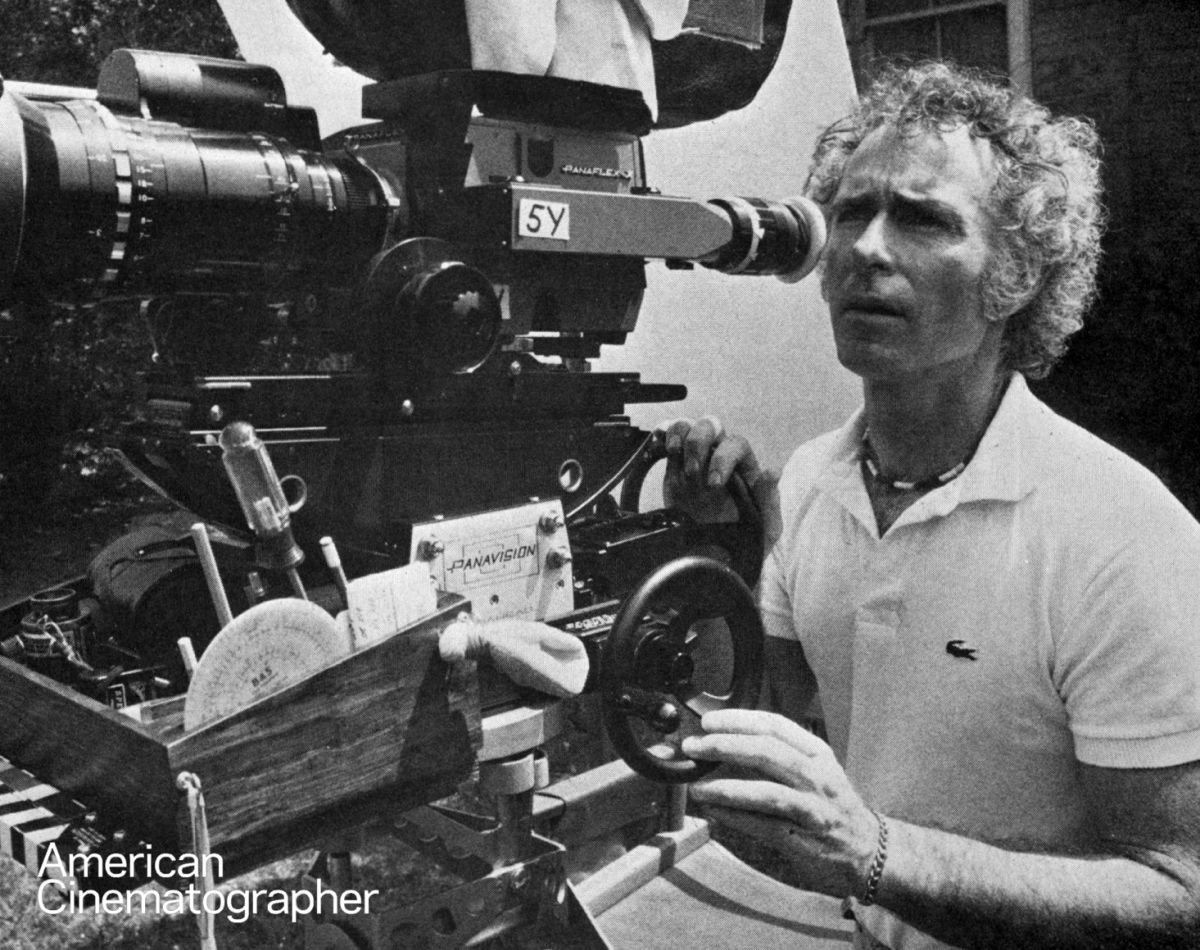

Behind the Camera on Altered States with Jordan Cronenweth

An assignment loaded with cinematic challenges, but also opportunities to photograph some of the most fascinating subject matter ever filmed.

This article was originally published in AC March 1981. Some images are additional or alternate.

Altered States is a film which shines with cinematic artistry in every element of its production. The photography is just one of those elements, but it is outstanding in the way that it serves this often-bizarre, visually fascinating film.

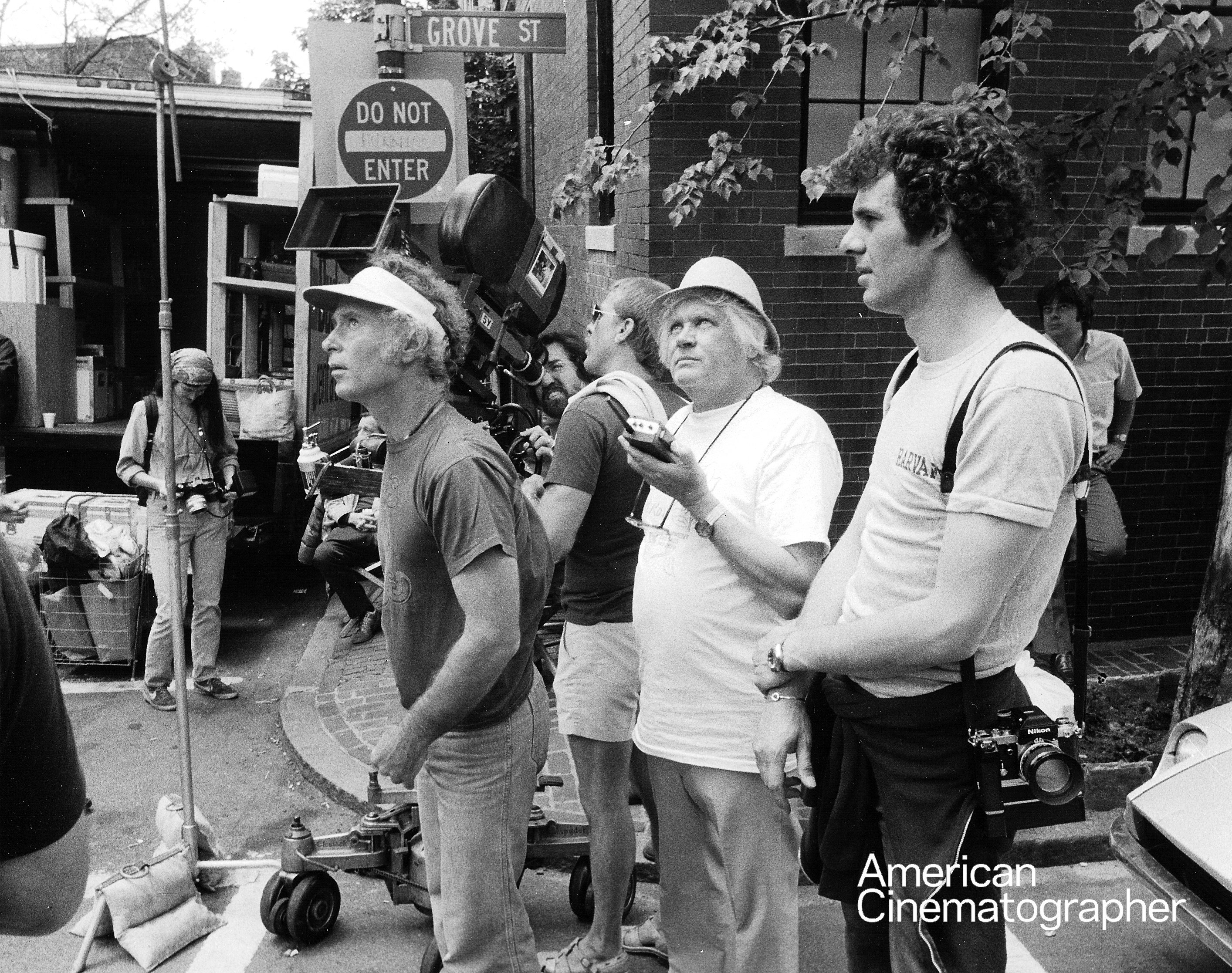

As director of photography, Jordan Cronenweth brought to the production a basically clean visual style that left room for plenty of spectacular mood and lighting effects when the subject matter veered away from reality and into the realms of the psychological unknown. Cronenweth’s list of prestigious credits as cinematographer includes: Zandy's Bride, The Front Page, Gable and Lombard, The Nickel Ride, Handle With Care and Cutter and Bone.

In the following interview, Cronenweth talks about the special challenges posed by Altered States and some of the methods he used to meet those challenges photographically:

American Cinematographer: When or how did you meet Ken Russell?

Jordan Cronenweth, ASC: The first time I was aware that Ken Russell knew of me, was when I read an interview with him in American Cinematographer, where he made some flattering comments about my work. I think he mentioned that he was particularly impressed with Zandy's Bride. At one point the film Valentino was going to be made in this country, and Ken Russell contacted me at that time. We had planned to get together, when suddenly the decision was made to make the film in Europe. Naturally, I was very disappointed. I actually met Ken for the first time when I interviewed for Altered States.

“We felt that since the story was as bizarre as it was, we would keep the photography very real and honest.”

— Jordan Cronenweth, ASC

How did that meeting go?

I told him I was a great fan of his, which I was and still am, and he said he was also a fan of mine. He proceeded to explain some of the more unusual aspects of the film, making me aware of its fantastic visual potential. Later, after driving home through heavy rain, I was delighted to hear from my agent that he’d already been contacted by Ken.

How did you arrive at the visual style or “look” of the picture?

We felt that since the story was as bizarre as it was, we would keep the photography very real and honest, using no filtration of any kind; just keep it clean, and if anything, try to create a feeling that something is going to happen... that there is a sinister presence always. Then, when the spectacular events begin to occur, the look would not interfere with the strength of their own “bizarreness” and power.

What would you say were some of your most difficult technical challenges in photographing Altered States?

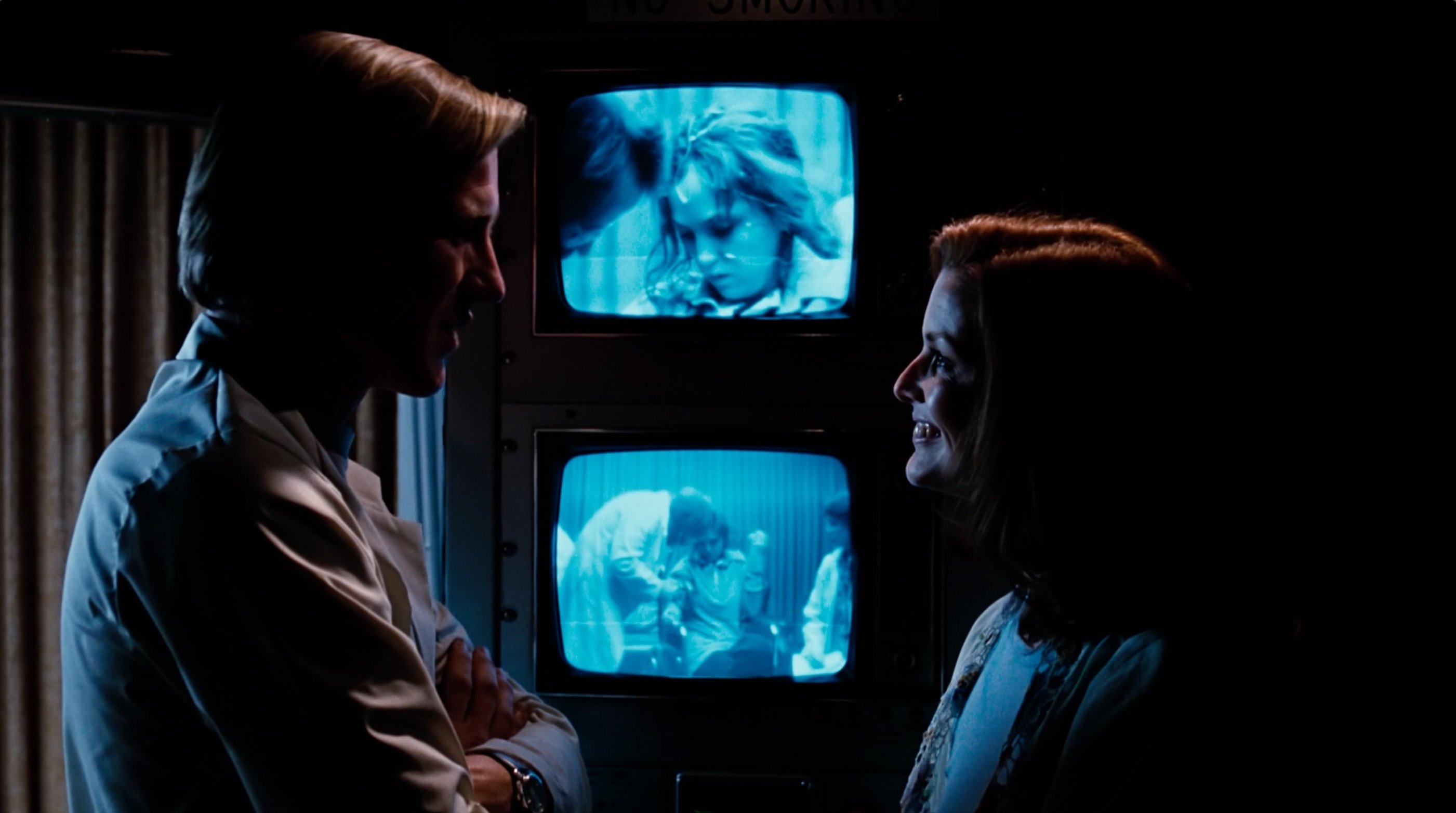

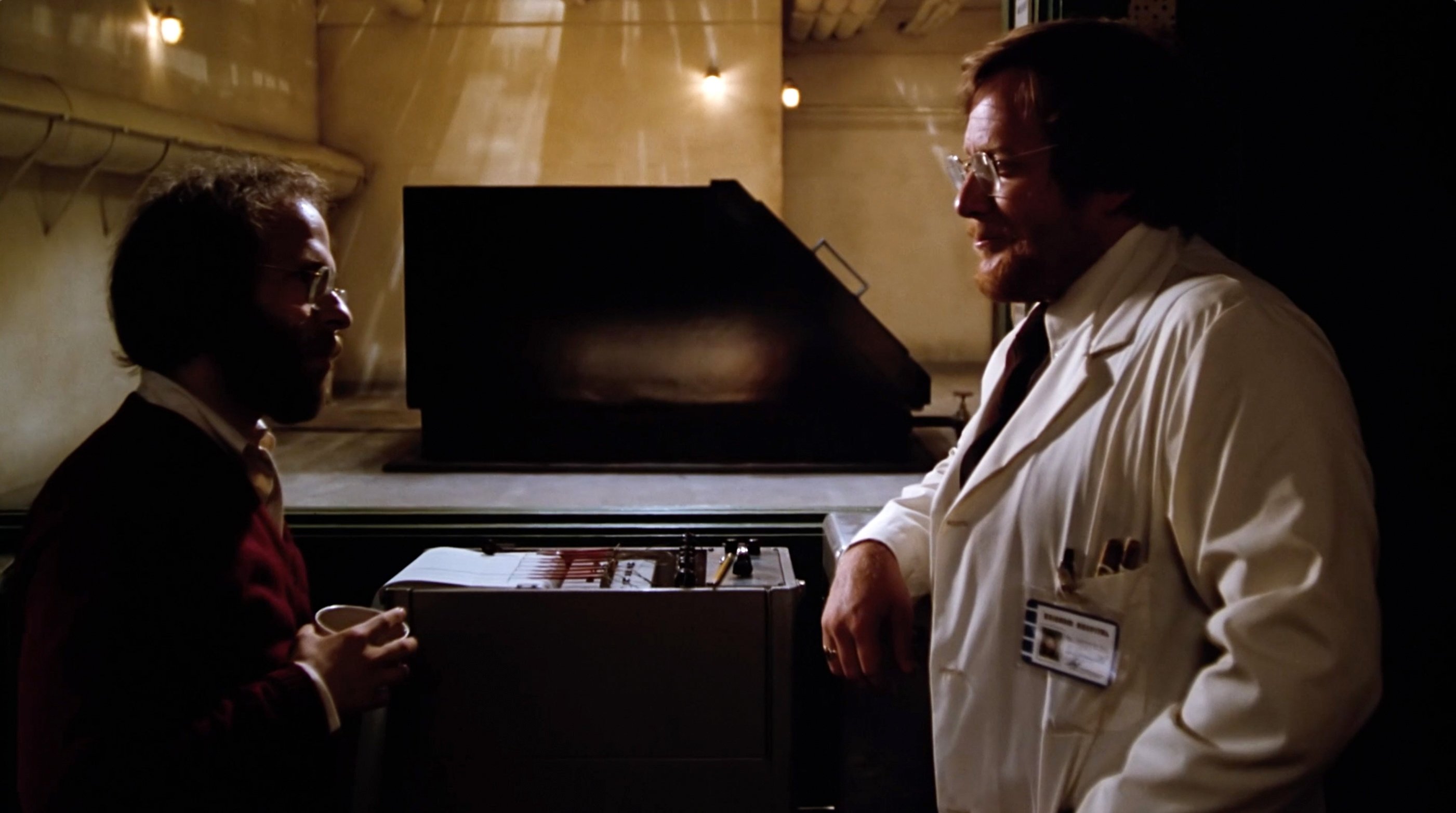

Some of the more challenging problems were posed by the isolation tank sequences. We decided that when Bill Hurt closed the tank it would be black inside, so one couldn’t see anything. We wouldn’t portray an unrealistic kind of situation where there is just enough light to see his face in the blackness, because, after all, it is supposed to be black. We got around that by the following: In the sequence when Bill changes from a human to a protoplasmic mass of pulsating energy, we had installed, story-wise, an infrared TV camera inside the isolation tank. That would be the image the characters were seeing on the observation room television monitor.

An infrared image is usually red where a heat source is indicated, but the images you have on the screen are not red. Any special reason?

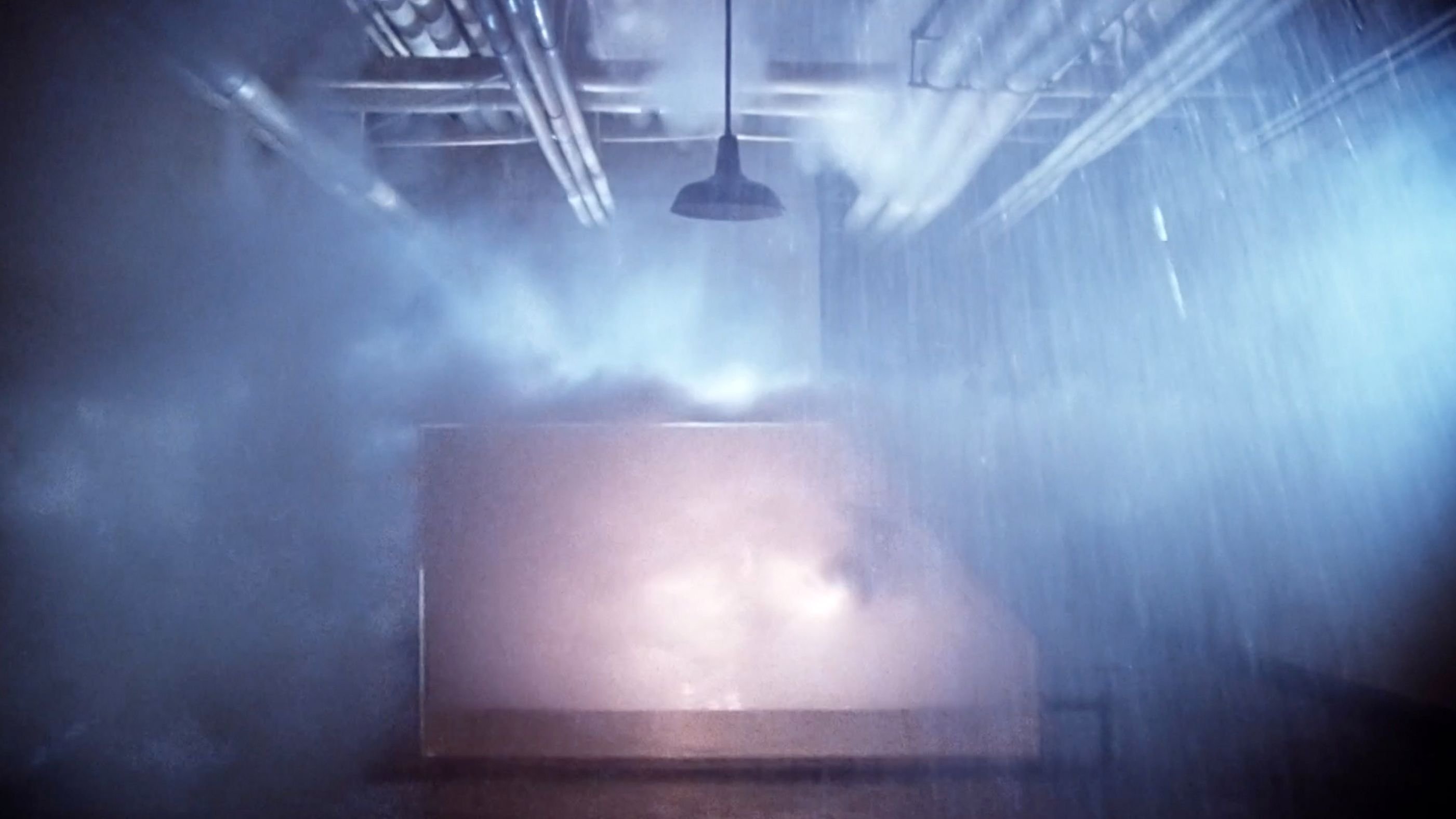

We experimented with the infrared image and decided to make it green. To digress for a moment: We were dealing with a form of energy in the story that was unique, and we chose to identify it with intense light. When things start to go awry in the last experiment, and Charles Haid runs into the tank room and opens the tank door, a tremendous amount of light comes out based on the idea that light accompanies the physical change that is taking place inside the tank.

Bran Ferren, who did the special visual effects, was consulted. I told him I wanted something that would produce shafts of pulsating light. As a result, he developed projectors, the basic unit consisting of a Xenon source which employed a rotating, multi-faceted mirror in the beam of that light. We used rectangular tunnels with mirrors on the insides of all four surfaces to conduct this pulsating mass of light, for example, out of the television set in the isolation room and out of the tank that Bill’s body is in. We employed these extensively in those sequences where he is transforming from human to protoplasmic mass. We also could control the frequency with which waves would emanate from the machine by virtue of the speed that the mirror would rotate. It was really a beautifully built unit.

You spoke of the pulsating mass of light coming out of the television set-up in the isolation tank and onto the monitor in the observation room. Could you elaborate on that a bit?

As things began to happen in the tank, we wanted to have the image on the TV monitor in the observation room change. First the picture on the monitor would start to fluctuate and eventually it would turn white, the idea being that the energy was transferring through the infrared camera in the isolation tank into the TV monitor and overtaxing its circuitry. So we wanted some kind of a light to project from the television set that had a characteristic that was unusual, as opposed to just a shaft of light. That's how we originally came up with the idea... that’s where the desire for the pulsating light originated from. It was so effective that we decided to use it coming out of the body, as well, since we had two machines. We wanted to create the illusion that the body inside the tank, as it is gaining energy, emits light energy from within. Unfortunately, some of the more successful attempts during the course of Bill’s transition from human to protoplasmic mass ended up on the cutting room floor.

Those transitions from human to protoplasmic mass were done in several stages. Could you describe them?

We had some wonderful stages. As a matter of fact, one of the visual experiences I enjoyed working out most was the idea that as the body inside the tank transforms, the energy becomes so intense that the tank becomes more and more transparent. To accomplish this, we built a duplication of the tank out of clear plastic. Then I had removable neutrals made up to go outside the plastic tank, so that it would eventually appear to be a black box — unless, of course, you had some type of light source inside. We did, in fact, build a body that approximated the shape of the protoplasmic mass stage of Bill's character. Then we placed dozens of photofloods inside the body. Special effects man Chuck Gaspar and his staff built the body out of a flexible, heat-resistant material. Even so, we still had to circulate air inside of it to keep it cool.

How were the photofloods controlled, in terms of intensity?

We put the photofloods on a transistorized modular dimmer panel — the kind used in rock concerts. We could then control clusters of globes individually, such as in the arms and legs. We experimented with different patterns of light progression within the body and came up with a pulsing effect as the most ideal thing. What we had in the total effect was not as it appeared in the film, but the potential was there for the tank to gradually change from a fully opaque object to a transparent object until it is so intensely bright that the body inside illuminates the entire room. We could only leave the photofloods on for about 60 seconds at a time, then we’d have to cut and let the body cool off for two or three minutes. It was a spectacular effect, and it worked out even beyond our visualization of it... beyond our hopes. But for his own reason, Ken Russell decided to reduce this transition period to just a few cuts, so most of this material didn’t end up in the film.

Were all of the transitional shots made using that plastic body form with the photofloods inside of it?

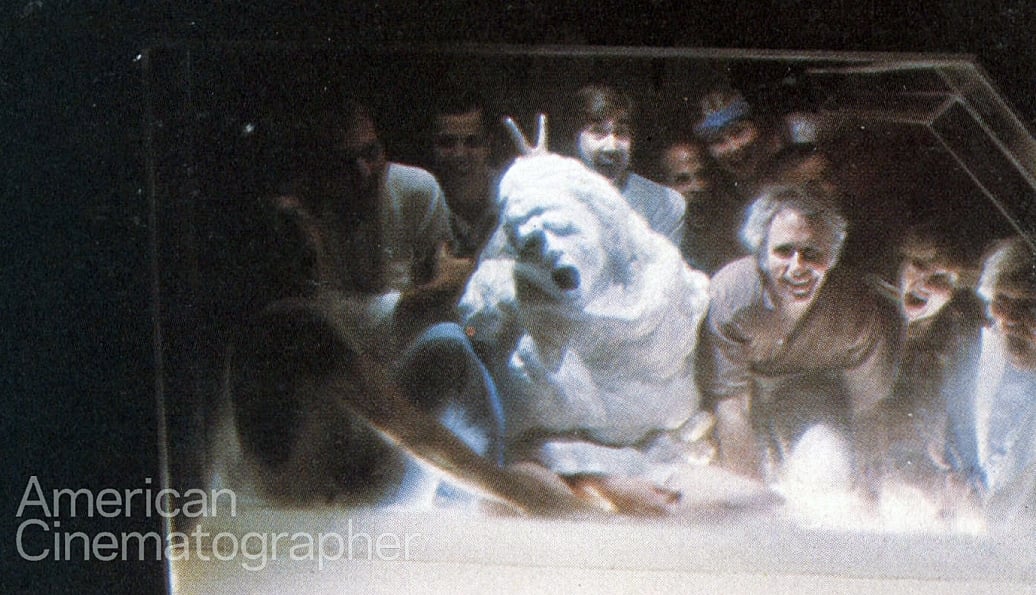

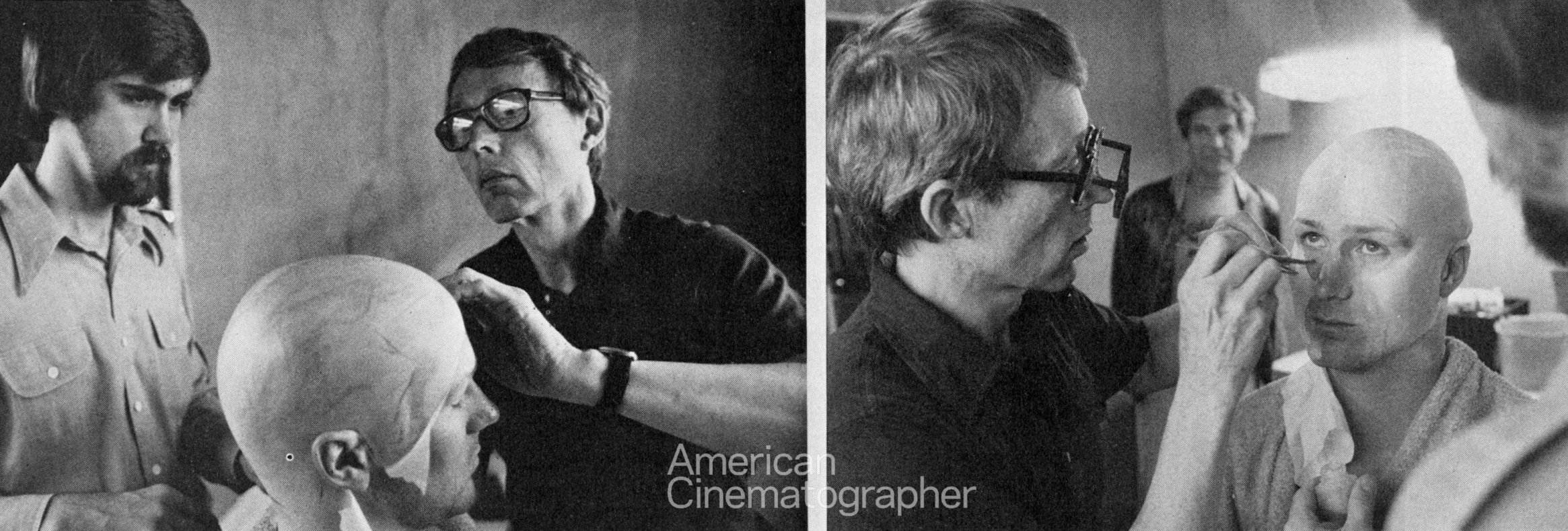

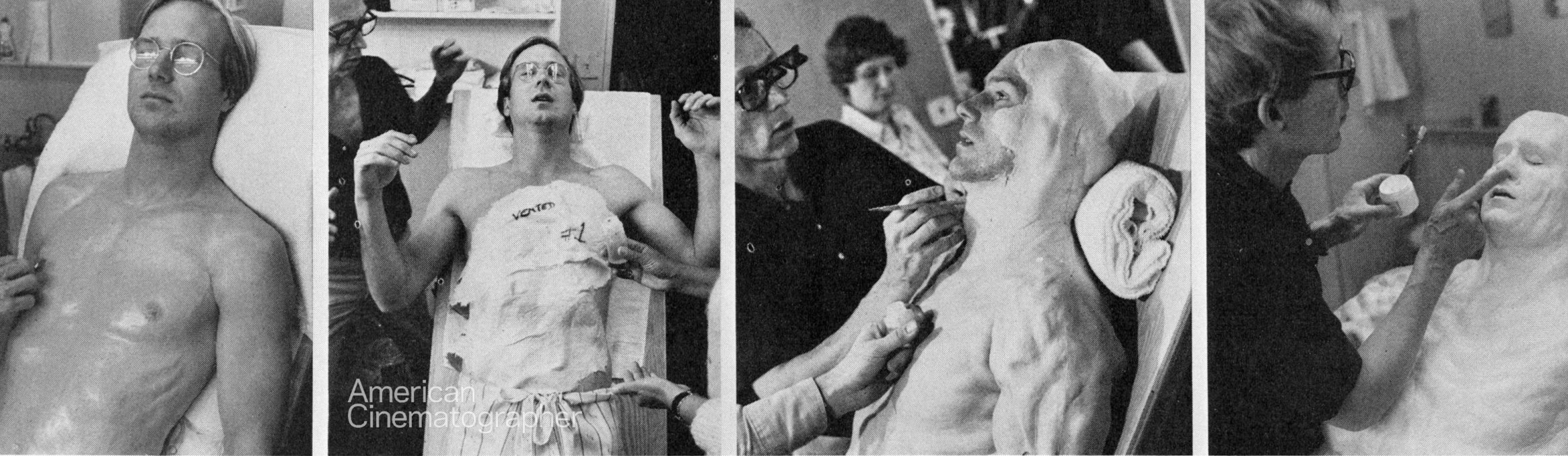

Despite all the time we spent developing the artificial body with the photofloods inside, Ken Russell was not happy with its limited movement. We then tried another technique. Makeup artist Dick Smith designed and built three stages of body suits for Bill Hurt, each less identifiable as a human. We painted these suits white, and after removing the floor under the tank-the bottom of the tank was clear plastic, we lit from underneath and above. We put smoke in a Plexiglass chamber in the tank between the actor and the camera. We then photographed with different degrees of brightness and different amounts of smoke and had some amazing results.

Again, only one cut of it is in the picture. Like so many things in a film like this, they develop as the are progressing, as you are shooting. We wanted to have the feeling that after the tank explodes and the room is filling with water, and Bill somehow disappears into the liquid, that light energy in the room is now coming from below the floor where he is supposedly going into the vortex. In order to accomplish that, we built a duplication of the tank room with a one-and-a-half-inch-thick Plexiglass floor. It was quite a construction project because it had to support thousands of gallons of water. It had to be elevated enough to be illuminated from beneath. Then we did the lighting with the greatest intensity of light at the center of the vortex and falling off to the outside. We had to put a special material in the water to make it semi-opaque so one see the vortex mechanism which was on top of the floor. We also used pink filters on the lights to remove some of the green caused by the light passing through unfiltered water.

What were the lighting problems you encountered in illuminating that plastic floor from below?

An interesting phenomenon took place with the vortex lighting. We lit the room without the vortex in operation because it required pumps outside the sound stage which were being overtaxed. We took readings three or four feet off the water where Blair Brown’s face would be and then turned the vortex on. It was like putting the whole thing on a dimmer. The faster the vortex would go, the darker the lighting would get until finally it was down to nothing by the time the vortex reached its proper intensity. It was amazing. What was happening as we introduced the vortex movement through the water was that it would concentrate the water in the path of the light, so that the lights were going through a much denser area. I had a dozen nine lights underneath at my disposal, so I had tremendous capacity. We finally ended up with every globe lit.

Once the primal man escapes from the basement, where did you shoot after that?

That was a combination of locations in New York, in the Bronx Zoo and on the back lot of Warner Bros. Garrett Brown did a lot of it with his Steadicam. He did a wonderful job.

How did you justify the light source inside the zoo?

Inside the zoo I justified it by going the moonlight route, with lots of tree branch shadows to break it up. I don’t think you are too conscious of source when you see the zoo material. On the street, that was easiest: Street lights. I used Titan arcs at the zoo because I wanted to keep the lights way back. We had large areas to light and couldn’t interfere with the animals. I put the lights on cherry pickers, one for each tree branch effect. It was very demanding for [actor] Miguel Godreau, who played the primal man. When his contact lenses were in, he had severely limited vision and could only keep them on a few minutes at a time. There was a slight drizzle and between takes, so Dick Smith and crew would frantically patch his makeup. It had taken something like four hours to get it all on to begin with, and now it was taking about five minutes to fall apart. By the way, Miguel was a dancer in New York and had never done anything like this before.

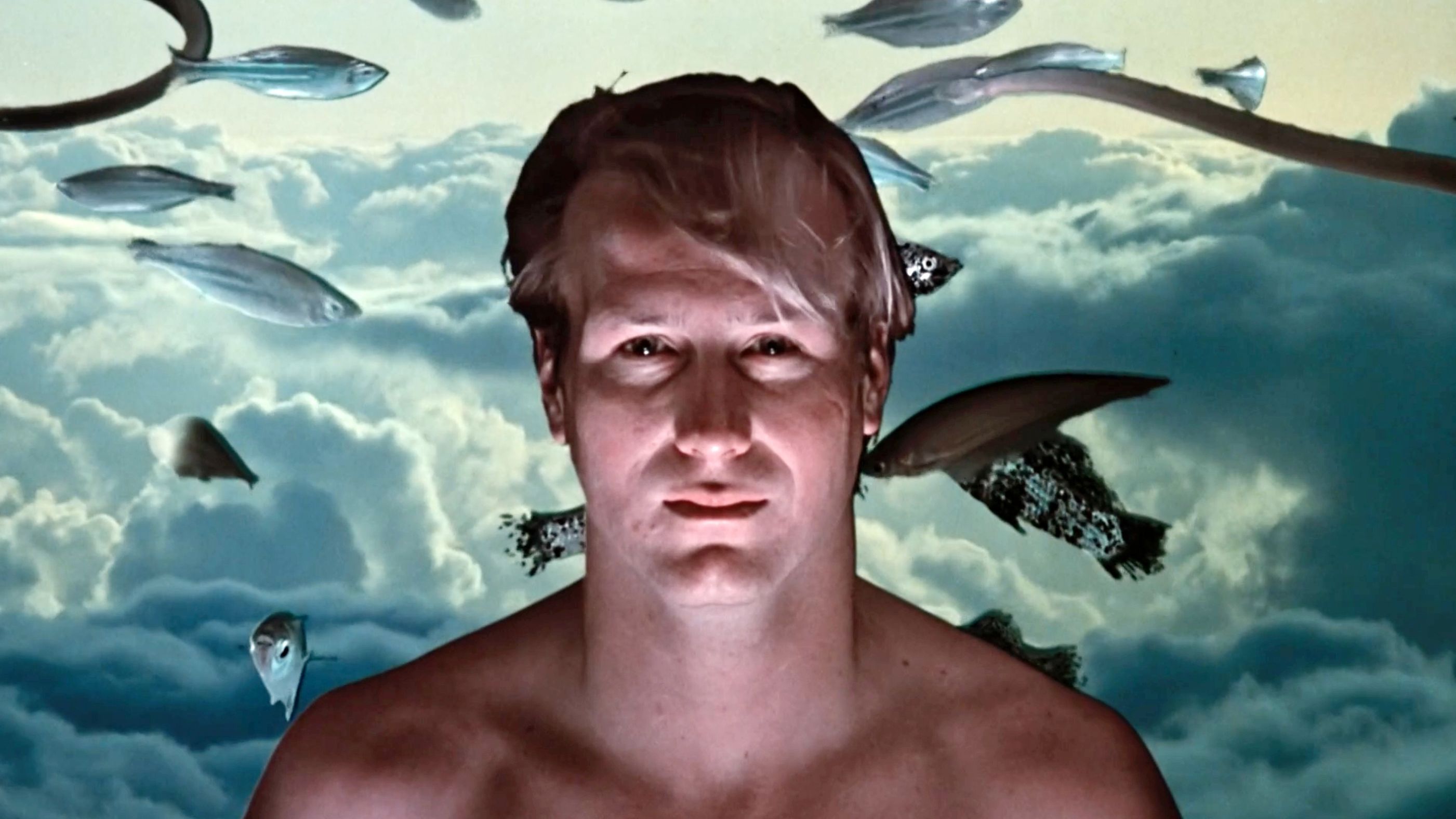

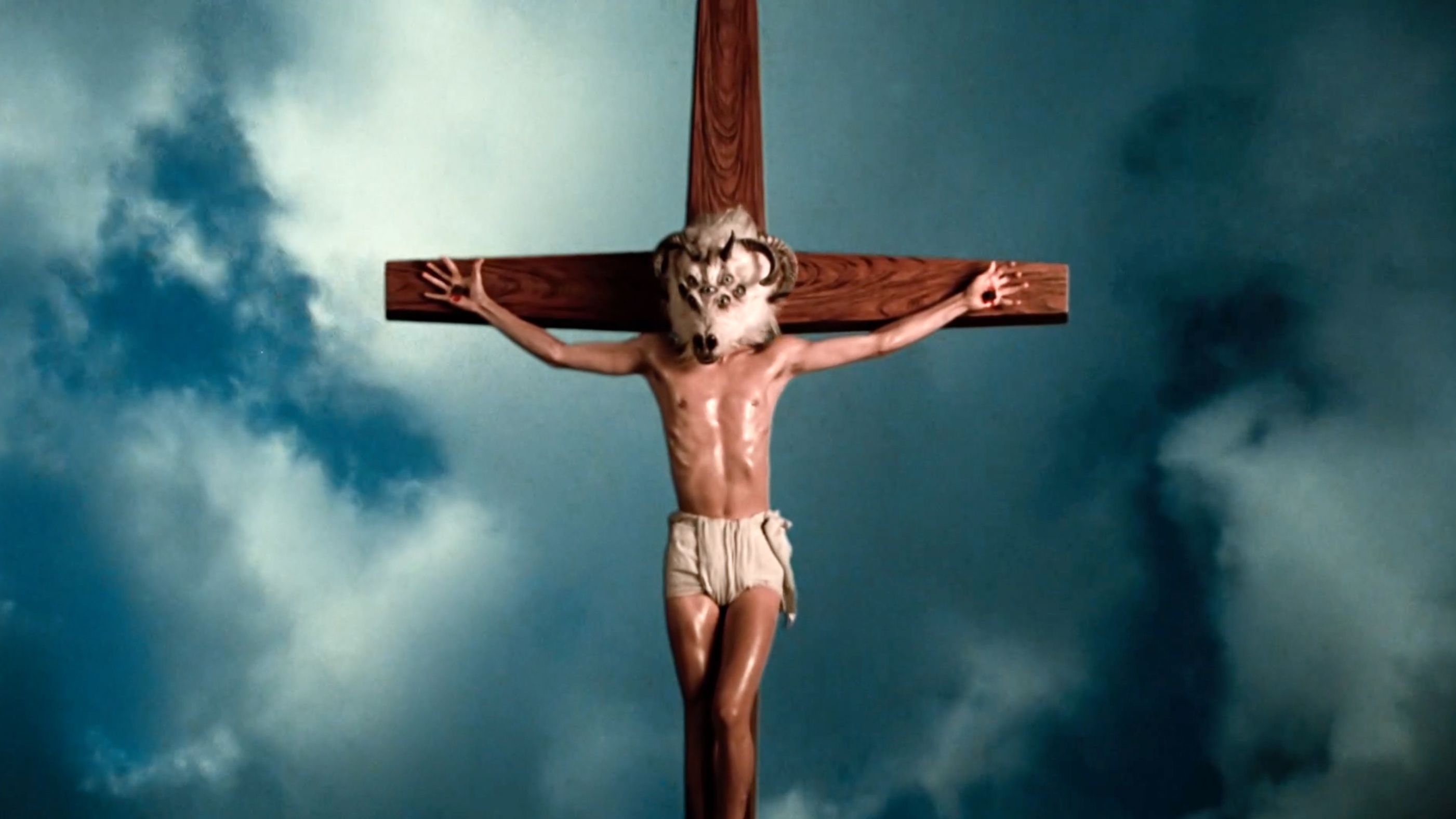

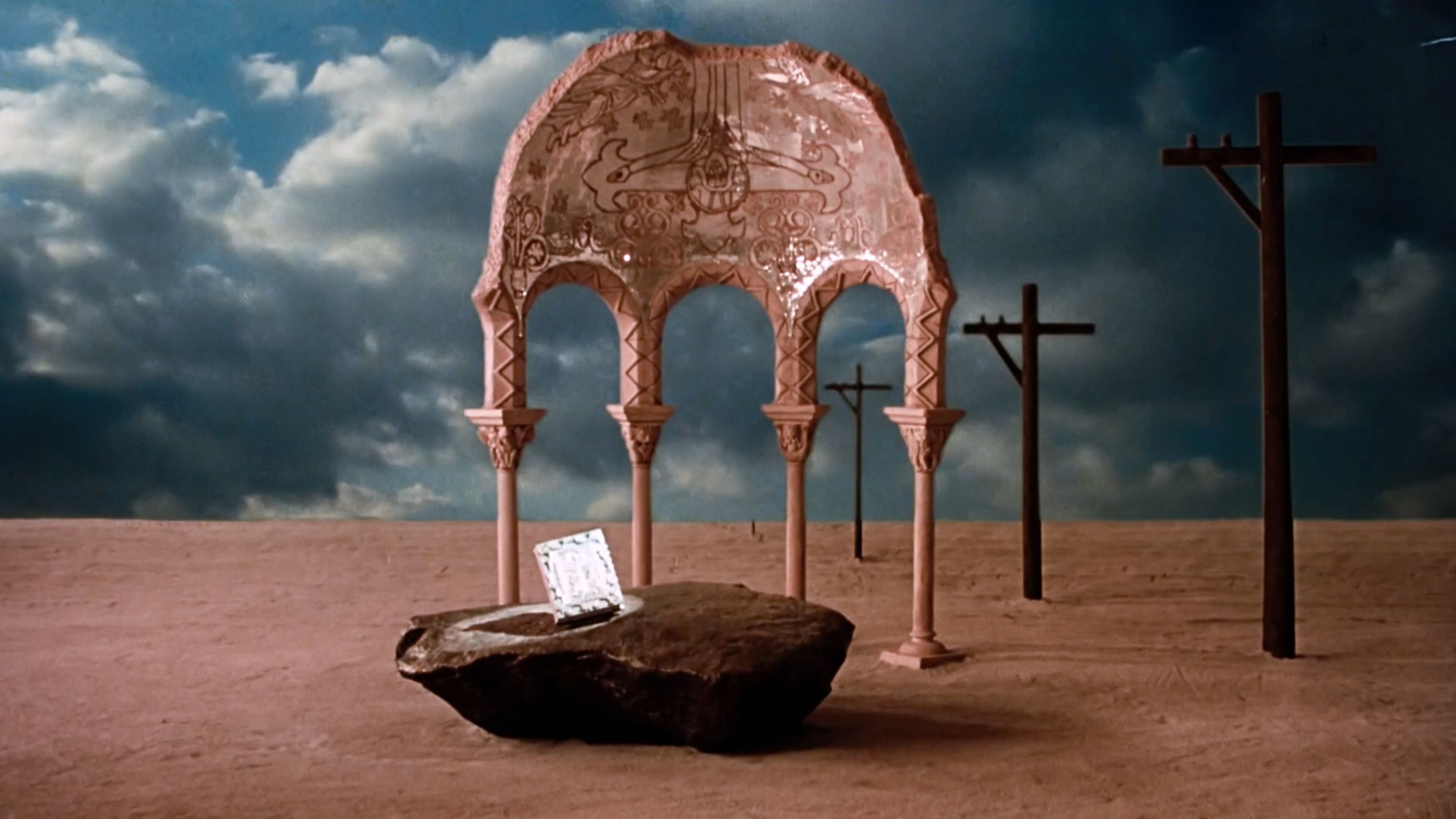

I understand that a certain amount of bluescreen matting was used in photographing Altered States. Could you comment on that?

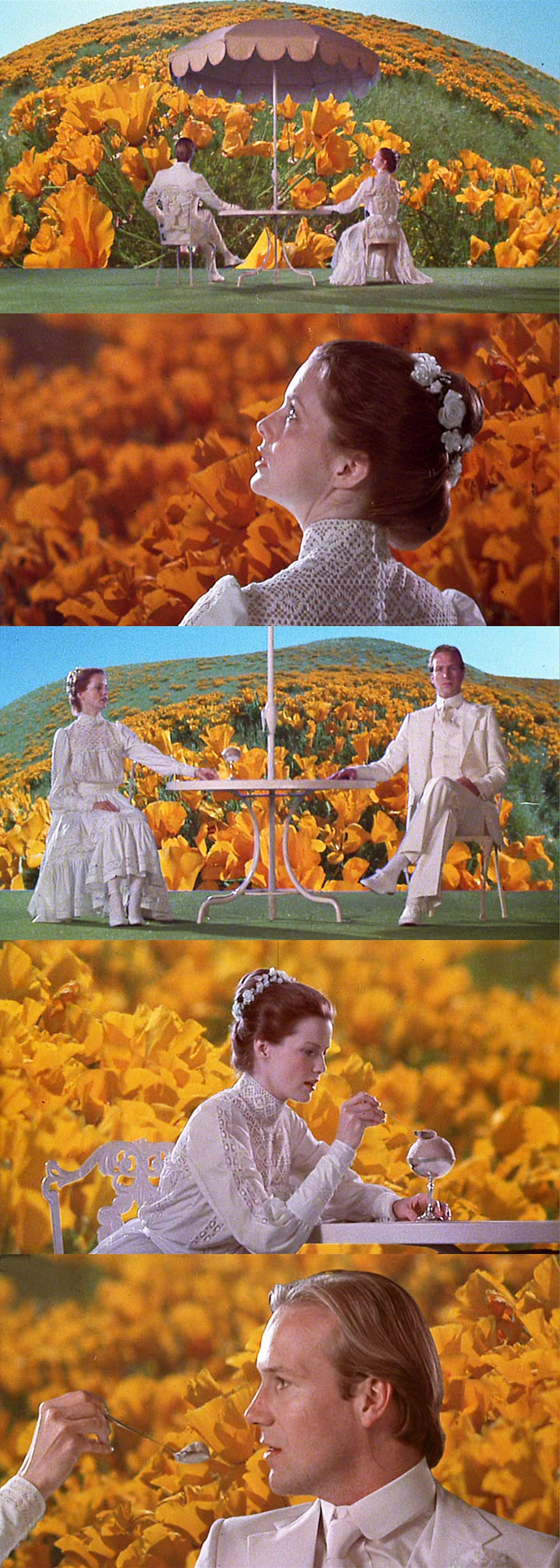

I was particularly proud of some of the blue backing work we did. I’m basically a low-key cameraman; I like to work from eight to fifteen foot-candles. Some of the blue backing photography we did in order to hold focus was shot with 1600 to 2000 foot-candles. It was really interesting to balance at those kinds of light levels. It was the first bluescreen experience I’ve had. Gene Polito came over the first day we started and gave me a few pointers. He hung around until he felt I had the knack; then I was on my own. A lot of that photography was done with over-cranking, which complicated things. I got more light out of Maxi-Brutes than out of arcs for this particular application. I was going through bleached muslin, and the Maxi-Brutes really got in there; the arcs didn’t penetrate it.

Where did you shoot the interiors for the primal man sequence?

That was shot in downtown Los Angeles, in the Biltmore Hotel. But that sequence was sort of conventional. I’d rather talk about things that are unique to the film.

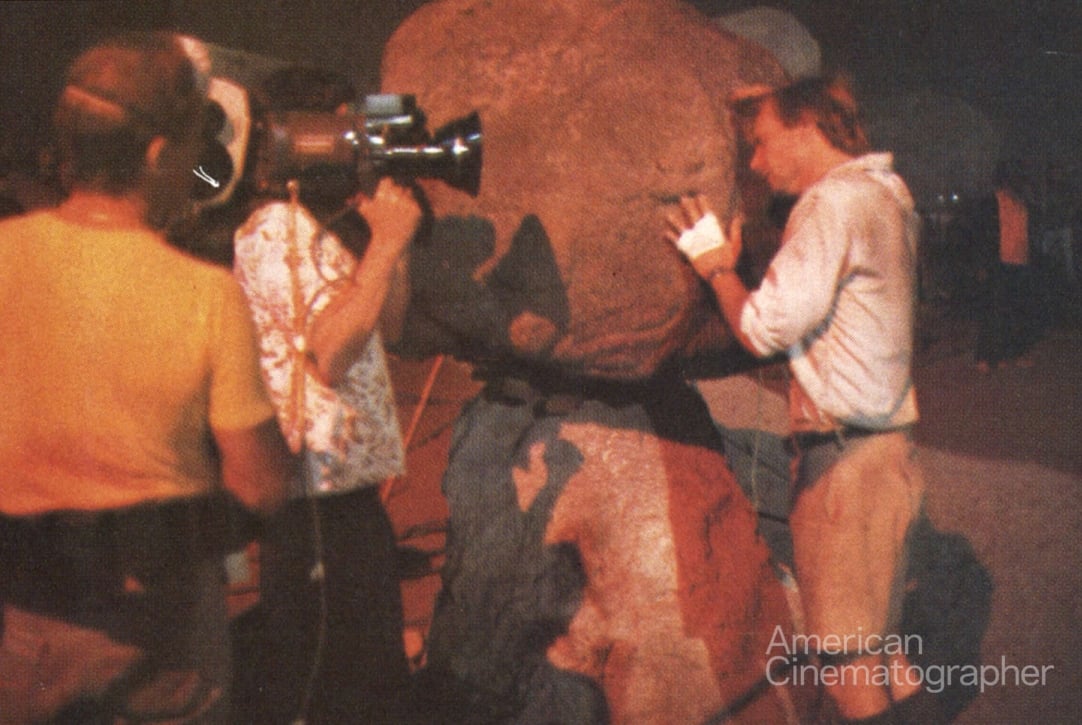

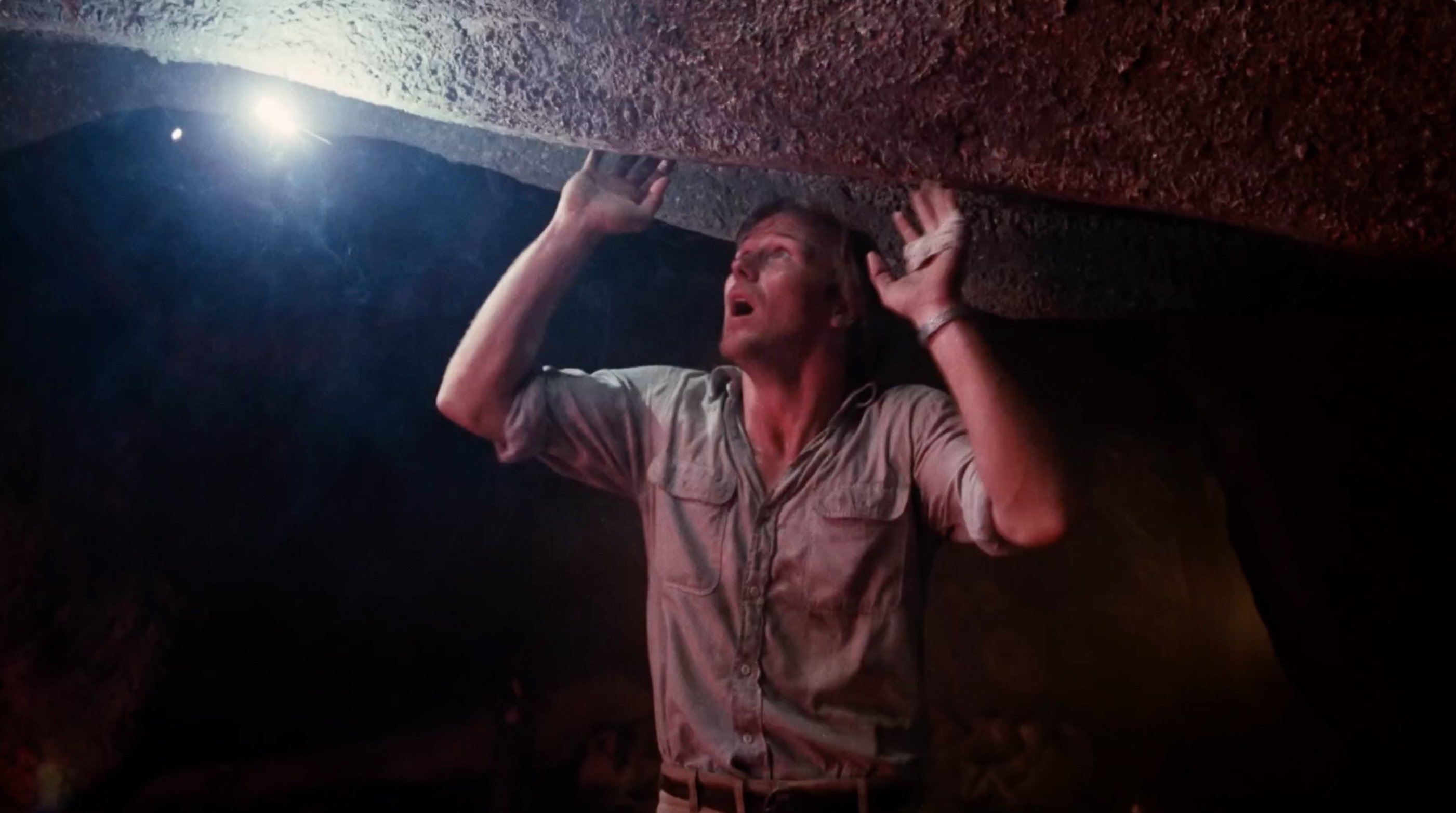

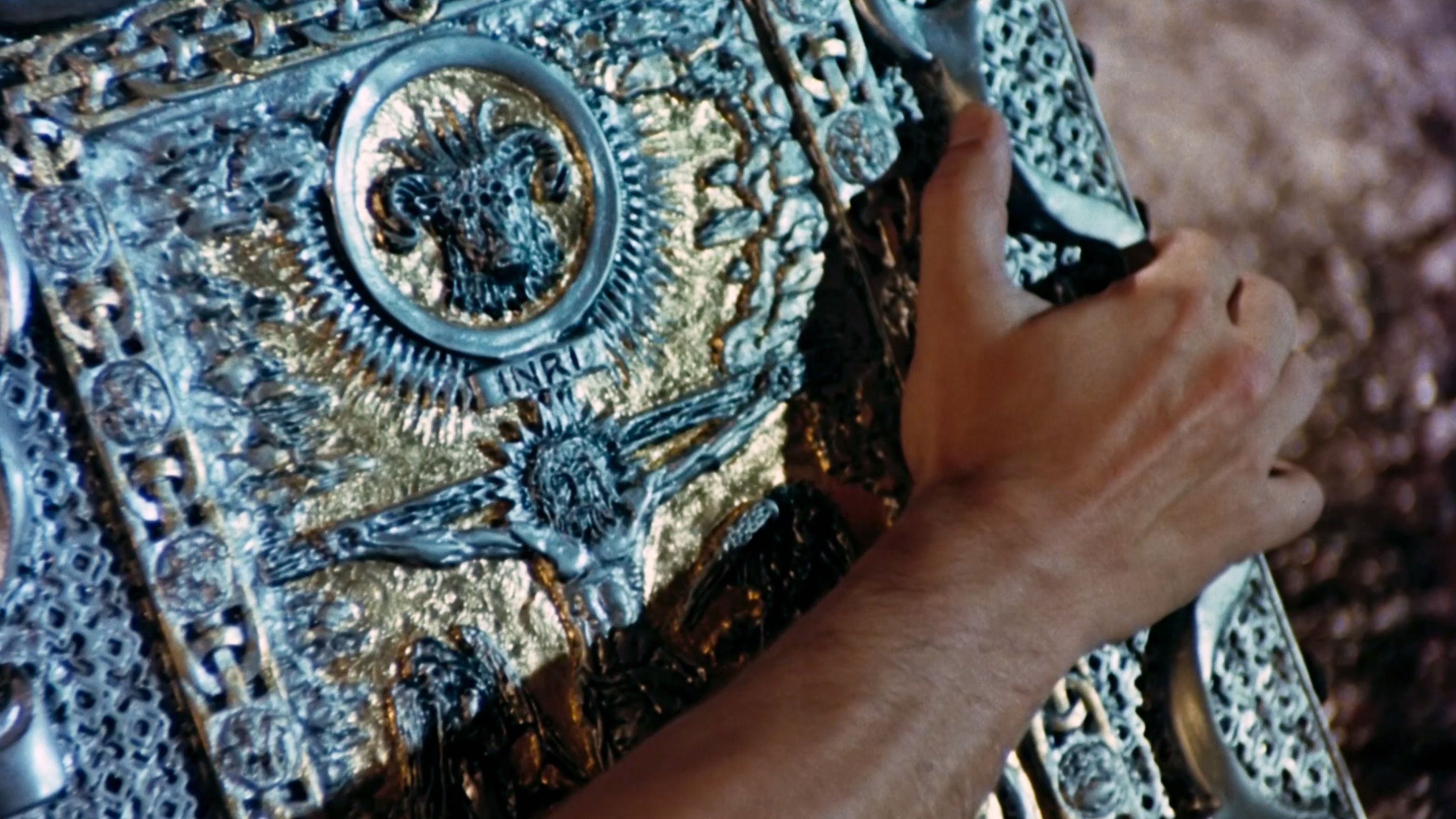

In that case, what about the cave sequence?

The most interesting part of the cave sequence, from my standpoint, was when Bill emerged from the cave after the fireworks had started. That sequence was actually illuminated by fireworks... in total. Bill drinks the mushroom brew and is beginning to go into a hallucinogenic state. The audience isn’t quite sure whether the fireworks are only in his mind or are actually there. I was quite pleased with the results

With a “light source” consisting solely of fireworks, how can you determine what your exposure should be?

You have to go by eye. Sometimes it’s a little too bright and sometimes a little too dark. You get comfortable at a certain light level after a few days on a film and you can pretty much tell what’s happening at a certain exposure in a situation like that. We were making so much smoke during the fireworks sequence that they had to call the fire department in Burbank to warn them what we were doing so they wouldn’t think the stage was on fire. Actually, the only thing that was burning was Bill, the special effects men, and, of course, the camera crew.

That was obviously a very interesting sequence to photograph. What other sequences were especially interesting from the photographic standpoint?

Another interesting sequence occurred toward the end of the picture — Blair Brown’s burning effect after she touches Bill. I would like to talk about that for a minute. She had on a suit which represented a charred body. It covered everything, including her face. It was like a mask, like a wetsuit.

Dick Smith is a wonderfully creative makeup artist. He applied Scotch-Lite material to the suit, which had crevices in it that were lower than the total surface of it. All the crevices were painted and they would branch off like veins and capillaries. What that amounted to was that her body became a front projection screen in places wherever this material was applied. We would front project an image onto her body — which turned out to be water bubbling with air — out of focus with colored gel lighting it from beneath. That was projected with the maximum intensity we could get out of the machine. We had picture everywhere as a result; on the floor, on the walls. In order to eliminate the undesirable spillage, we masked off as much as possible, then painted the walls black. In the final result you see in the film, her body has a volcanic glow.

What was Ken Russell like to work with?

He was wonderful because, for one thing, he is highly conscious of light sources and will always be interested in new ideas, often coming up with some of his own. It was his idea, for example, to use the heater as the light source for the first love sequence in the beginning of the picture. I also enjoyed Ken’s strong visual sense, and was particularly intrigued at how he arrived at the “Ken Russell Look”. He has a definite style that is very strong and predominates in all his films.

Your statement about the “Ken Russell Look” intrigues me. Could you give me a specific example of that?

One example of pure Ken Russell goes something like this: It concerns the scene in which Bill Hurt is standing in the hallway to the living room of his apartment and Charles Haid has arrived with his clothing. Ken wanted Bill silhouetted against the wall in the living room. We lined up the shot with the second team, and lit it so he was nicely silhouetted. Now the living room was totally furnished, livable. When Ken Russell got behind the camera and he saw the actors standing there, he wasn’t happy with the silhouette. It wasn’t clean enough for him, so he started removing furniture. The next time you see the picture you will notice that there is not one single item of furniture in the living room. No pictures on the wall, no tables, chairs, it’s all gone... everything. Here, you take a living room that’s been established several times during the course of the film and remove all the furniture from it; you'd think that somebody would catch it. Not one person has ever made a comment about it. Now that is the “Ken Russell Look"

Cronenweth followed Altered States with films including Blade Runner, Peggy Sue Got Married (for which he won the inaugural ASC Award for Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography), Gardens of Stone, U2: Rattle and Hum and State of Grace.

His son, Jeff Cronenweth, is today a member of the ASC.