John A. Alonzo, ASC Discusses Blue Thunder

"CINEMATOGRAPHY IN THE 1600 ZONE" — Testing high-speed film stocks, ranging from 1000-2000 on the Exposure Index.

This article originally appeared in AC May 1983. Some images are additional or alternate. Unit photography by Bruce W. Talamon.

Blue Thunder was one of the first extensive tests for the newly-introduced Eastman color high speed negative film 5293 under extreme shooting conditions. Kodak recommends rating the high-speed film for an exposure index of 250 tungsten light. However, John A. Alonzo, who has been known to do this sort of thing before, probed for the far reaches of the emulsion’s latitude.

After some extensive pre-production testing, Alonzo decided to rate the high-speed film for E.I.s of 1000, 1500, 1600, 1750, and even 2000 in various scenes where he wanted the latitude to hold the image crispness and sharp depth of field that director John Badham prescribed for the Blue Thunder look.

The following interview with Alonzo covers his experiences during the production of Blue Thunder, as well as a few comments regarding his subsequent work with high-speed color negative film, and some observations concerning what the cinematographer has learned while shooting on the frontier of E.l. 1600 and above.

“John Badham wanted a clean, crisp look with no diffusion. He wanted it to be realistic. However, you have to consider that realism is in the mind of the beholder.”

American Cinematographer: How would you describe the look or photographic style developed for Blue Thunder?

John A. Alonzo: John Badham wanted a clean, crisp look with no diffusion. He wanted it to be realistic. However, you have to consider that realism is in the mind of the beholder. Our audience is mainly made up of people who grew up watching film footage from Vietnam on television every night. They know what helicopters look like. They also know what a police car looks like going down Hollywood Boulevard at night. Those are the images that they relate with reality. You can’t do that when you have splits and soft backgrounds. We did some handheld camera work. But, it was always for a purpose. There were a few scenes where John wanted to give the audience a visual hint that something was going to happen — maybe a slight feeling of tension. We worked mostly with hard lenses. Even when we used a zoom lens, it was generally set at a fixed point. Make no mistake about it, John choreographed this picture every step of the way. He knew exactly what he wanted. He knew each twist and turn that he wanted the helicopter to take as it battled over the city. When we used a dolly shot, it was always to get a precise point of view. He was very strong about all of this. Details such as how long the guns should fire; the intensity of an explosion; when we should overcrank or undercrank a little to alter the visual perspective; using a slightly wider angle lens in a scene where he wanted Blue Thunder to appear somewhat more menacing; or calling for a particular reflection on the ’copter window; he called all of those shots. A slight exaggeration of visual reality in the end made it all seem that much more real. What I am most proud of is that we were able to deliver the images that John wanted without making the audience aware of the camera. The idea was to make the audience forget they were watching a movie for two hours. Blue Thunder is a fantasy, an escape film, and its success will be determined by its ability to involve the audience.

You indicated earlier that you had six weeks of preparation time for Blue Thunder. How did you use that time?

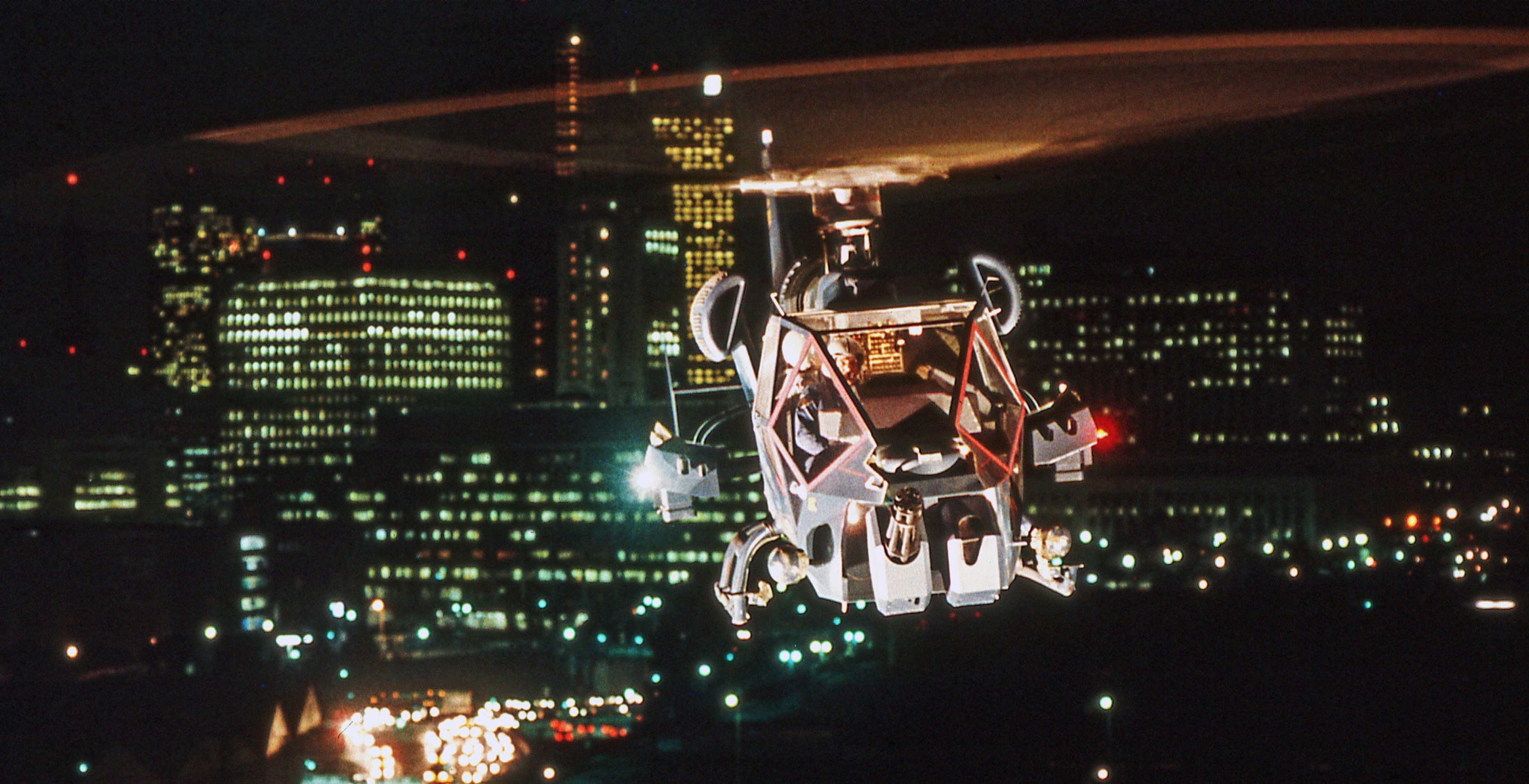

This prep time was very important to the success of the film. John and I did things like riding in Los Angeles police helicopters at night so we could see how the panel illumination fell on the pilot’s face, and how the lights from the city reflected on the windows. I had a chance to do some work with the art director [Bernie Cutler] on such things as what color to paint Blue Thunder so it reproduced the way John wanted it. By the way, I was really pleased that they designed Blue Thunder with all of those square lines and windows. I think that made it look more menacing. It also made it easier for us to control the reflected light in the process shots, which basically was front projected. Of course, the prep time also provided an opportunity for us to shoot some extensive tests with 5293.

Blue Thunder was shot at various practical locations in and around the Los Angeles area, and we did our process work and some other stage scenes at Burbank Studios. Dick Barlow, head of the camera department there, arranged for the pre-production tests. I concentrated on the types of scenes where I feel that the high-speed emulsion was most needed. We shot a series of tests from a helicopter flying over Los Angeles at night. We used VistaVision camera with a 50mm lens. I was planning to use that format to produce our plates for the process work. We wanted the sharpest possible plate; however, there isn’t that much depth-of-field in the 50mm lens that you are limited to using with VistaVision. Obviously, if we could work at a higher E.I., we could work at a better T-stop, and get more depth of field.

We shot tests rating the film for E.I.s of 250, 500, 1000 and 2000. When we used the higher E.I.s, we were shooting at T-3.5 and 4. Instead of the ground lights “blossoming” as they do with a larger aperture, they looked natural, and you could read details in the shadow areas. I was also very excited about the process shots that we did. In this case, we were using a Panaflex camera with a prime lens. By working at a smaller aperture, we were able to hold sharp focus between the plate in the background and characters in the foreground. John is a director who speaks the language of film technology. He understood how we could use the high-speed film to make our process shots look much more realistic, and how we would also be able to avoid splits and keep both characters in the cockpit in sharp focus when that was the effect he wanted.

What was the result of the pre-production testing of the high-speed film?

I would have liked to have done the entire picture with the high-speed emulsion. Unfortunately, we were starting production before 5293 was generally available. [Producer] Shel Schrager went all out to get us as much of the high-speed emulsion as he could. In the end, we only received around 40,000 feet of 5293, which we had to dole out very sparingly for our night process scenes, a couple of night practicals, and for the conclusion of the film. We were also able to shoot one of our night plates over Westwood with the “fast” film. I give Shel and [executive producer] Phil Feldman a lot of credit for their willingness to take some chances on both a new emulsion, and on rating it for E.I.s of up to 2000.

Tell us about the emulsion used to shoot the rest of the film, how you rated it, and how it mixed with the 5293.

The rest of Blue Thunder was shot on Eastman color negative II film 5247, which I primarily rated for an E.l. of 400, which is two stops higher than what Eastman recommends. We needed that extra latitude because Blue Thunder was filmed with anamorphic lenses. Since we couldn’t use “hot” lighting on our night process shots, or even on key night practicals, the only way that we could get the depth of field that Badham wanted was by increasing the E.l. to 400 so we could work at stop T5.6 or 6. I didn’t see any objectionable grain. I also didn’t see any objectionable grain when we rated the 5293 at E.l. 1750 for our night process work. As for how the two negatives mixed, I don’t think that anyone can sit in the theater and pick out scenes where we switched from one emulsion to the other. I feel that the color contrast you can get with 5293 is a little softer than 5247. I personally prefer that look, however, the difference isn’t so glaring that there is a problem in mixing the two emulsions.

With the mixing of two stocks, and the various E.I.s, your relations with the lab and the color timer working with you must be very important.

Next to my crew, I count on the lab most, especially the color timer. [Technicolor did most of the 5293 lab work for Blue Thunder, and MGM Lab did the 5247 work with the 70mm release prints by DeLuxe.] What we did was establish the print lights that we were going to use with different E.I.s in different situations. For example, right now I am shooting Scarface at Universal. We have one very big set with red walls, where I am rating the 5293 for an E.l. of 1600. Technicolor prints the scenes that I shoot on that set 22 yellow, 30 cyan, and 30 magenta. We have another set where the walls are black. On this set, using the same E.I., the lab prints 25 yellow, 29 cyan and 30 magenta.

In other words, you are under or over-exposing the film in situation where you feel that this is called for, and you are having the lab compensate by correcting colors and densities?

There are also situations where I have rated 5293 for an E.l. of 125 for daylight exteriors and compensated by putting an 85N9 filter in back of the lens. On a cloudy day that was generally enough. On brighter days, I added a 30 neutral density filter to the front of the lens.

Is it possible to single out one photographic challenge on Blue Thunder, and say that this was the most difficult thing to achieve?

That’s a fairly easy question. The most difficult part of this film was marrying all of that process work with the live aerials and making it seem real. Of course, this is an old problem for the movie industry. Remember those Westerns that were staged on trains, when the cameraman had to make you believe that the sequences shot in a studio were really happening out on the prairie? Well, we had the same situation, only our prairie was the skies over Los Angeles, day and night.

Whenever Roy Scheider was supposed to be flying, we had to do our close-in camerawork on a sound stage against the appropriate plate. But there were also times when he was a passenger, pretending to pilot while the real pilot flew the ’copter off camera. There is one aerial shot, where Scheider is wounded, that looks so good, you would swear it had to be a process shot. The sun was coming through the window right over his shoulder just as we shot a bullet hole through it. As good as that sequence was, we were very dependent upon our process shots, and these took a lot of concentration and a great deal of careful planning.

“We shot our aerials around the city on Sundays, when the police could cordon off the areas we were flying over for safety reasons.”

The night sequences helped because it was easier to hide small units. On the other hand, we had to be very careful not to brighten up the background so much that it didn’t look like night. Here is one area where the E.l. 1750 that we got with the 5293 really paid off. We could put a 75mm lens on a Panaflex camera and work at stop T5.6. There was no ambient light on the plate, but we were still able to keep the actors [when there were two in the cockpit] and the background in sharp focus. I realize that in the theater, the audience is looking at Scheider in the cockpit and not the background. But, if the background is a little soft, if there’s a spot of light without a believable source, I think that it registers, at least with some people, if only subconsciously. It rings a silent alarm in their minds, and signals them that this isn’t really a helicopter flying above Los Angeles. That kind of feeling can move through an audience very fast, even if no one says anything. On a picture like this, you need the entire audience to believe the fantasy and react accordingly. There were some other things which we did that helped the illusion. We shot a lot of the process work with two Panaflex cameras, which we put on cranes with Continental mounts. I think that was Mike Ferris’ idea. It created a fluid motion, which very closely matched the actual aerial sequences.

Can we talk some about the actual shooting of aerial sequences?

I’ll start by saying that Jim Gavin probably doesn’t have any peers when it comes to flying a ’copter for camera. As I mentioned earlier, John [Badham] choreographed every aspect of these sequences. It was almost like watching a ballet. There were a couple of sequences where we had time to do some handheld camerawork from inside a cockpit. However, most of the time, the lens openings on the Arri cameras used for this purpose were preset since photography was done from mounts outside the copters. When we had time, Frank Holgate and I would both go up in two ’copters, and we would try to come to an average reading between us. The problem was that there were many variables. Cloud cover could blow in or out. And, the copters could move from the skyline into the shadows between buildings. Frank’s aerial experience was invaluable and, fortunately, we had a great deal of latitude in both emulsions [5293 and 5247], so this didn’t prove to be too great a problem.

Shel Schrager told us about one scene, which he said amazed him. Roy Scheider is driving down Hollywood Boulevard at night. He stops for a red light. Your camera comes in from the front, and over his shoulder you can see a store in the background. If you look carefully you can read the labels on the shelves. How did you do it?

This was a sequence where we used 5293 rated for an E.l. of 2000. Even with all of the help that we got from the police, there was no way that we could have cleared and lit Hollywood Boulevard at night. In fact, I’m not certain that we would have wanted to. One of the things that this emulsion does, is let you see things the way that the human eye does. The only light that we used on this particular scene came from a small fiber-optics unit. The illumination appeared to be coming from the dashboard. We had eight, maybe 10 foot-candles. The shot was on Roy at a stop of T2.8. It looked just the way it would have if you were there looking at him through this front window. In reality, backgrounds don’t go soft. If you were there that night, standing where our camera was, you would be able to read the labels on the shelves, too. The fact is you have to be very alert when you use this emulsion. It “sees” things that we aren’t used to worrying about. If you shoot an interior, and there is a window in the background, it is likely to see what is outside. You can’t count on the background behind the window burning out.

You raised another point. How did you do all of that shooting around Los Angeles, particularly the low-level helicopter work?

We had tremendous cooperation from the city, including the police and fire departments. We shot our aerials around the city on Sundays, when the police could cordon off the areas we were flying over for safety reasons. They also provided a heliport and other locations where we shot key scenes.

When we were talking earlier, you also referred to several multi-camera sequences involving speed work. Can we go over that again?

There is one sequence very early in the film, where the capabilities of Blue Thunder are being demonstrated for city officials. They set up some mock up scenes, where Blue Thunder is brought in to shoot up dummies of terrorists. The idea is to show off special capabilities that Blue Thunder has for picking off targets in a crowd. That’s where you get a big clue that something is wrong, since the pilot also blows some big holes in “friendly” dummies, and a government agent explains to city officials that a 10 to one ratio isn’t too bad. There is a lot of high-speed action going on — the ’copter swooping in and out. There are explosions all over the place. We didn’t want to lose a foot, so we had eight cameras covering the scene from every conceivable angle. That included a couple of Panastar cameras, which we used at speeds of up to 120 frames per second to stretch out the explosions. These are very effective cameras for this purpose, since they start out at speed from frame one.

There was an even more difficult sequence, which occurs at the end of the movie. Scheider has won his battle. He has shot his nemesis out of the air, avoided being shot down by various flying SWAT squads, and has done away with an F-16 fighter, which has already done some considerable damage to downtown Los Angeles. Now, it’s nightfall, and he is left with the question of what to do with Blue Thunder. He sets it down on a railroad track in front of a speeding locomotive. There is a tremendous crash, explosion and fire. You don’t want to shoot that more than once if you can avoid it. Here again, we had eight cameras covering the scene, including a number of Panastars with frame rates set at 48, 72, 96 and 120 per second. We used some small PAR units to create pools of light coming from believable sources. There were maybe 50 foot-candles. Badham wanted to use a zoom lens on this scene. This was on time when we did use a zoom effect. Our E.l. was 1600 using the 5293 emulsion, and I think that you have got to see that scene yourself to really appreciate the kinds of things that this high-speed emulsion makes possible. The combination of shooting speed cameras at night with deep focus capabilities is simply amazing.

You mentioned having subsequently done several other films entirely with the 5293 stock.

Cross Creek and Scarface. Cross Creek was shot entirely on location in Florida. It is mainly daylight exteriors. But, much of the movie is shot in a swamp with very heavy cover. It’s lush green and pretty dark. I mainly rated the film at E.l. 1000 for interiors, and our brighter exteriors were rated at E.l. 125 with the darker ones at 250. The film showed tremendous latitude. It never blossomed in the sun, but it still pulled in those details in the shadows. We obviously couldn’t string cable and haul generators through the swamp. In this situation, all we needed were a couple of 9 lites and maybe a single FEY on the camera. In contrast, on Scarface, most of my interiors were shot at E.l. 1600. Our bright exteriors were shot at 125, and then at 250 and 400 in darker outdoor scenes. It all mixed well.

Why were you shooting interiors on a sound stage at E.l. 1600?

Because I wasn’t brave enough to shoot 2000! Actually, since I’ve had an opportunity to experiment some more with lighting for the 5293 stock, rating it for an E.l. of 2000 seems like a usable idea. I think that this film “sees” light something like the iris on an electronic camera, if I can make that comparison. It will zero in on either a very dark or a very bright picture; however, if you light very precisely, it can also provide a tremendous range of scale. If I am in a situation where I have or want to use low-contrast flat lights, and at E.l. 2000, my meter tells me that I need 25 foot-candles to work at T-5.6. What I would do in that situation is go up to 30 foot-candles, and I would get a very crisp image as compared to what I would get at 25 foot-candles.

I understand that you have tested some Eastman color high speed negative film 5294 while shooting this picture? What is your reaction, so far?

Eastman recommends using this film at an E.l. of 400 as compared to 250 for the 5293, which it will replace. My reaction is that the new emulsion is about 1⁄3 of a stop faster, and it is also a little finer grained. I like the color balance very much. We shot tests at 8000, 6000, 4000 and 2000 E.l. just to see what would happen. At 8000 E.I., we had three to four foot-candles in front and 10 to 15 overhead on a giant set, and I shot at stop T5. I came down to T4.5 at 6000 E.I., 3.5 at 4000, and 2.8 at 2000. From what I have seen so far, I wouldn’t hesitate to do a theatrical film at an E.l. of 2000, if that was what we needed with 5294. I can see a use for even higher exposure indexes for TV films. Of course, you have to be very careful when you are shooting a scene with seven or eight foot-candles. When the lighting is this subtle, the film is not going to be very forgiving if you make a mistake. However, the trade-off for that is an opportunity to be tremendously mobile and creative in your use of lighting. The potential financial impact upon production is enormous. And if you are in the cast, you have got to like getting out from under those hot lights. None of this even gets into optical effects, or such special techniques as snorkle cameras, which have always required a tremendous amount of light.

How about projecting some of the things that you can foresee happening as a result of all of this in the near or long-term future?

I believe that we will go through a learning process just as we did after we got Super Speed lenses, the Steadicam and Panaglide, and other new tools. You have people like John Badham and Brian DePalma pushing the state of the art along now. Among the things which could follow are the use of more miniature light sources, including fiber optics, requiring very low wattages. This means that you can build housings which require less wattage, and are therefore cooler and easier to handle. And you can also begin to make better use of Fresnel lenses for focusing light. I don’t think that 10Ks will disappear. They shouldn’t because they make beautiful light. But, maybe we can make them run at lower wattages, which means that we will be able to work with fewer and smaller generators. This has some very broad implications. If we are putting smaller lighting units and generators on the truck, it means that you can carry more fixtures on location. You can be more creative. We should also be able to make better use of AC power sources at practical locations, since it becomes more feasible to use the smaller AC-powered lights.

How about lenses?

In Blue Thunder, we used long lenses at night at stops T4 and 5.6, and we got some very nice images exposed in 25 foot-candles. We have never been able to use these lenses at night before without bringing in a lot of light. I also think that we will be able to save producers some money by cutting back on the need for speed lenses. In fact, lens manufacturers might want to take another look at the need for speed lenses, and think of them in terms of stop T2.8, which means that they can take some of the glass out, reduce the weight and cost, and make them sharper and more mobile.

Learn more about the production in this article about the film’s visual effects, models and miniatures.

If you enjoy retrospective and archival coverage of classic films, you'll find much more here. And for complete access to every issue of American Cinematographer since 1920, subscribe here.