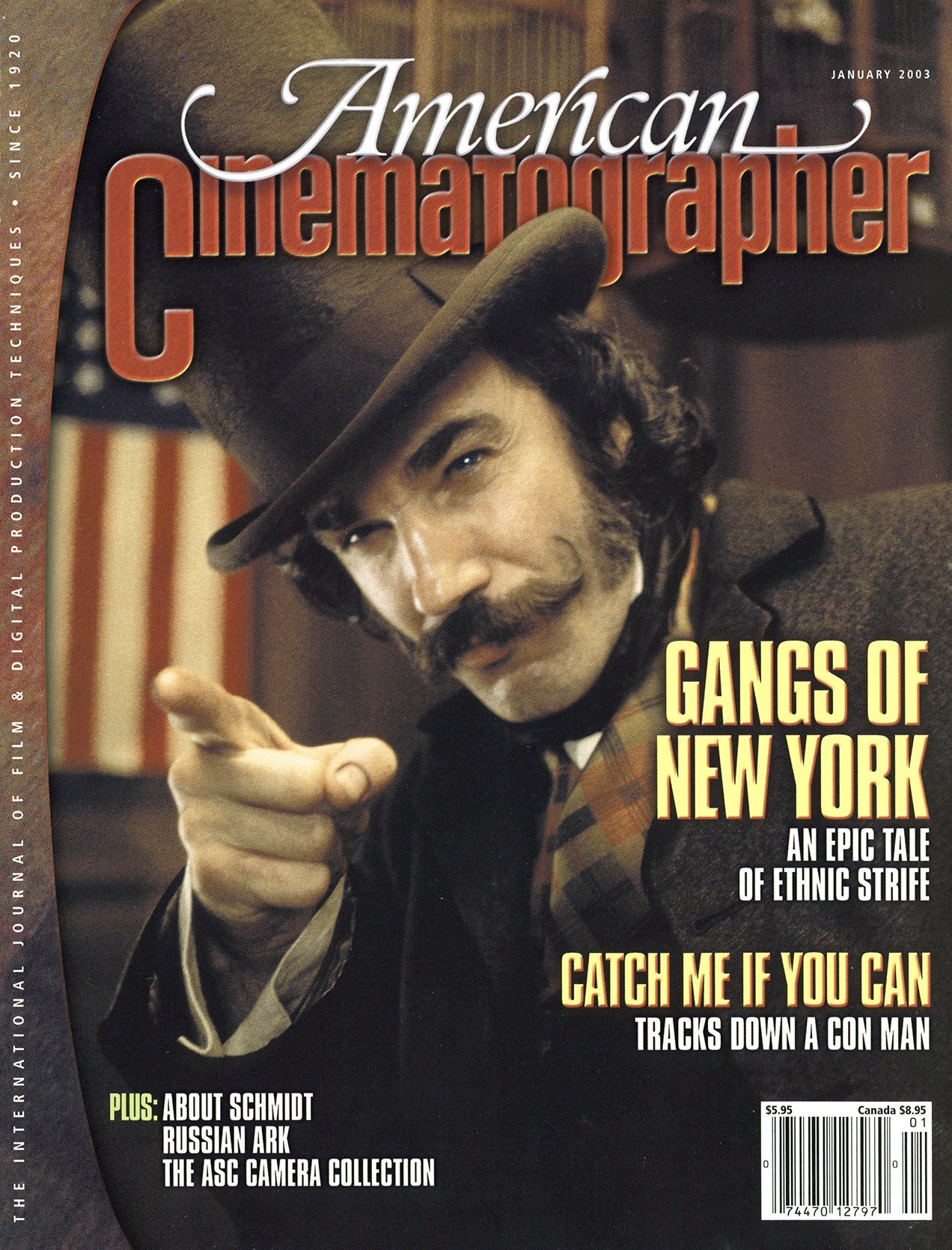

Karma Chameleon: Catch Me If You Can

Janusz Kaminski and his crack crew reteam with Steven Spielberg for this a breezy caper about a master of disguise and deceit.

Unit photography by Andrew Cooper

Photos courtesy of DreamWorks Pictures

From 40 years’ remove, it can seem like almost "anything went" back in the 1960s. Sex, drugs, and rock ’n roll were many teenagers’ bread and butter back then, and many graying Boomers can now wax soporific about their long-gone wild years. But even in those heady days, Frank Abagnale Jr.’s exploits turned heads — the heads of FBI agents, to be precise.

Catch Me If You Can, an effervescent holiday thriller directed by Steven Spielberg and photographed by Janusz Kamiński, is based on Abagnale’s memoir of the same name. Starring Leonardo DiCaprio as Abagnale and Tom Hanks as the FBI agent hot on his trail, the film depicts Abagnale’s teen years, during which he flawlessly impersonates pilots, doctors and attorneys, lives a playboy lifestyle on forged checks, and outmaneuvers the FBI for years before finally getting caught.

The project marks a distinct departure for Kamiński and Spielberg, whose past collaborations have focused on grim historical events or sinister sci-fi dystopias. "Catch Me If You Can deals with serious stuff — Frank spends the whole movie stealing and breaking laws, but he does it with such charm and panache that you sort of forgive him," says Kamiński. "This movie is pure entertainment, and it’s supposed to make you feel better. We definitely need those kinds of movies just as much as we need the serious kind."

One aspect of the project that was not a departure for Spielberg and Kamiński was the pace at which it was filmed: more than 180 scenes in 53 days, with locations in Los Angeles, New York and Montreal. "Our pace was standard Steven," Kamiński acknowledges.

What facilitated that pace was a quick-thinking crew whose key members had collaborated with Kamiński on many other projects. Among them were gaffer David Devlin and camera operator Mitch Dubin; Catch Me If You Can was Devlin’s eighth collaboration with Kamiński and Dubin’s tenth. AC recently interviewed Kamiński, Devlin and Dubin separately about their work on the film.

American Cinematographer: Janusz, this is your eighth film with Spielberg. Did it take you into any new territory?

Janusz Kamiński: Each movie we do has its own sets of demands and corresponding lighting styles. Steven is evolving from being a classical backlight/warm light director into someone who’s interested in things besides traditional beauty, and I think I play an important role in that. His work with other cinematographers was always sort of the same [because] they were servicing his very traditional aesthetic. I do that, too, but I’m also trying to imprint each movie with my own style, and I hope to slowly change Steven’s ideas about what’s beautiful.

This film is less ‘Spielberg’ than some of his other movies. Steven was very relaxed and interested in working with the actors, and because we were working so fast there was often not enough time to give him a traditional look. There are gorgeously lit scenes in the film, but there are also scenes that, well, just don’t look as good! Once we lit we just had to go with it. I love that method.

What kind of visual research did you do during preproduction?

Kamiński: I watched two documentaries: Frederick Wiseman’s High School and the Maysles brothers’ Salesman. I watched them not for lighting ideas, because both films are black-and-white, but for the story and characters. I wanted to see what the world was like when Abagnale was operating. High School was useful because it’s all about how awkward kids are, yet how mature they feel compared to the adults around them. And Abagnale’s father, Frank Sr. [played by Christopher Walken], was just like the salesman in Salesman; he lived in a world of pretending, of hoping that the next day would be the one where he’d strike gold.

What sort of testing did you do on this project?

Kamiński: Leo is 27, and he portrays a character that starts out at age 16, so most of our testing was concerned with how to photograph him to make him look younger. But the way Steven and I work, it’s hard to finesse lighting to accommodate the technical details of an actor’s characterization. To a certain degree, I lit Leo a little bit flatter when Frank was younger and created more textured light when he was older. But we were doing 22 setups every day, plus moves, so there were certain compromises.

despite the fact that he's never flown a plane in his life.

How did you decide to render the Sixties and Seventies photographically?

Kamiński: This movie’s photography is very straightforward. There are no tricks, no major CG work. [Production designer] Jeannine Oppewall found such wonderful locations to dress for very little money, and the wardrobe department created such great costumes, that the period was pretty much set. I didn’t have to enhance anything with special filters.

Mitch Dubin: The dressing of the movie — the great sets, period automobiles and wardrobe, and the fantastic locations Jeannine found — posed unlimited possibilities for the camera. No matter where you pointed the camera, it was hard not to find a great shot.

Kamiński: I would compare the film’s look to a bottle of champagne: when you pour that first glass and hold it up to the light and enjoy that warm glow, you just want to drink it in and get happy. So the lighting style is very warm. When we enter the Seventies, I went for a slightly bluer and pastel-like look, purposefully trying to make the images flatter and uglier. I used low-contrast and fog filters to accomplish that. I also shot [Kodak Vision] 320T [5277] stock, which I’ve never used before because I consider it too flat. I wanted this movie to go in that direction.

David Devlin: ‘Flat’ means different things to different people, though. Janusz is very specific with his sources and their direction, and his idea of flatness doesn’t mean he’s filling in light from every angle. It just means that the source is placed closer to the camera. For example, on some of the close-up work we used the Seven-Minute Drill. [Developed on Amistad, this book-light unit consists of an enclosed source aimed at 12'x12' Ultrabounce, which directs the light through a 12'x12' sheet of 1/2 Soft Frost.] That’s a large source for a close-up light, so it’s rather flat in that regard. [Key grip] Jim Kwiatkowski and I call it ‘dead light’ because there really isn’t a source to it. To give it a more sparkly look, we sometimes put in a hard source along with the bounced source behind the half Soft Frost; the hard light could be a stop overexposed, and the soft light might be two stops under. When Janusz uses hard light in his sources like that, or one soft source with no fill on the other side, he calls it ‘flat,’ but it’s actually very rich because you feel the falloff of light on the faces.

What philosophy about camera movement and framing did you work out to support the look you wanted?

Dubin: With Steven it tends to be a one-camera shoot. Even on Saving Private Ryan’s D-Day sequences, we used three cameras at most. Steven is very clever about how he uses the camera to tell the story; it’s never just a passive observer, so it’s not usually necessary to do a lot of multiple-camera coverage. He always has in mind how he wants the film to evolve, but many of our framing decisions on this film also had to do with being on the location and watching what the actors did during rehearsal. As an operator, you respond to everything you see. When all of those elements were combined with Steven’s overall concept, it became fairly obvious where the camera needed to be.

Kamiński: In other movies, the camera moves from left to right or pushes in. On a Spielberg movie, we’ll do that but then whip around 270 degrees. We didn’t have a lot of handheld shots in this film, but we never have straight tripod shots, either. Still, like Gordon Willis [ASC] said, everything falls apart once the camera starts moving. You can only light well for one camera angle, maybe 15 degrees. The way Steven moves the camera leads to many compromises on my part, but I love it. That’s why I’m making films instead of taking stills. They may not be the most carefully lit movies, but they sure are good movies!

Did the film’s lighthearted tone affect your decisions about its visual style?

Dubin: You shoot a movie one scene at a time, one take at a time, and the overall effect and concept of that shot isn’t really present in your mind when you’re shooting it. In fact, when you read the script for Catch Me If You Can, you might see it as a movie that isn’t buoyant and upbeat. As the organic process of making the film began, it started to develop that way. That’s how Leo and Tom presented their characters, and that’s how Steven directed them. The general attitude on the set was that it was a lot of fun to make this movie. Part of that could have been the script, part of that could’ve been the fact that Steven was in such a good mood, and part of it could’ve been the fact that Leo and Tom are such great guys and such good actors. The gestalt was an upbeat film.

You had a lot of practical locations for a 53-day shoot. How did the speed at which you were working affect your decisions?

Kamiński: Every day we were doing a whole set of mini-moves, and almost every other day we were doing major company moves. I’d love to work on a movie with a 90-day schedule that allows me to light for three hours and make careful compositions. Well, maybe I’d like to do it once; after that, I think I’d be fed up because it’d be so boring! I’d rather allow the director more time to tell his story and support him as quickly as I can.

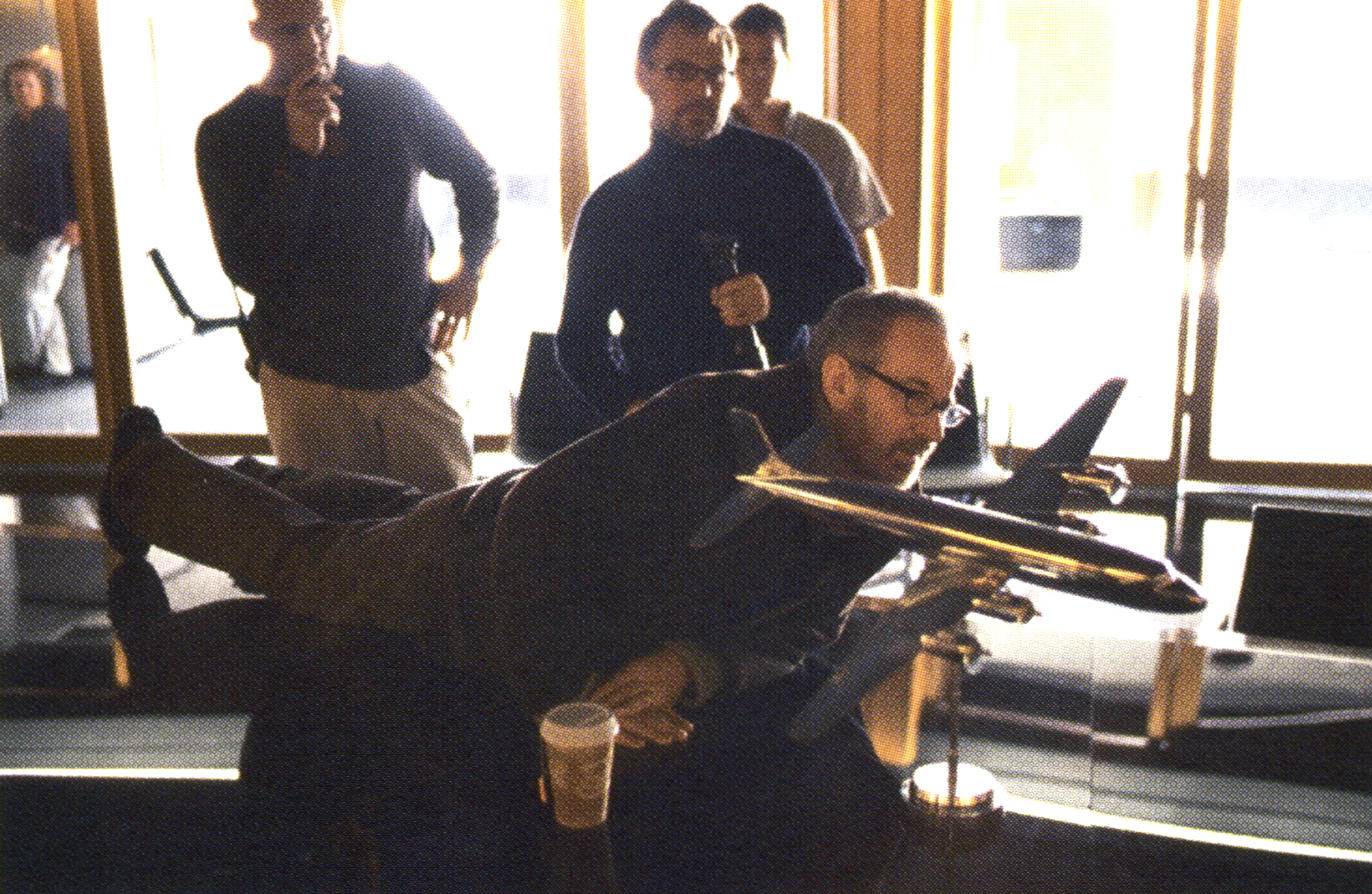

Devlin: The speed is largely about maintaining momentum. Steven would rather give up a great shot than not get the action he’s looking for right then and there. Sometimes when we say, ‘That take wasn’t good for us,’ he’ll reply, ‘Well, you missed your chance, because it was good for me and we’re moving on now.’ He’s a wonderful guy, but he’ll put the fear of God in you if you try to spend another 20 minutes lighting when he wants to go! So I’ll pre-light the set and have it ready to roll in a way that I hope will allow Janusz several directions to build off of spontaneously. The way Janusz works is rather like cooking: you can spend a lot of time over it, or you can just go with your gut and find that it tastes better than something you slaved over. Janusz isn’t a big schemer. He works with what’s in front of him, so he sees what he can actually get in each shot.

Maintaining lighting flexibility on location comes down to having a lot of amperage that’s reliable and available. The partnership that Evan Green from Paskal Lighting gave us was essential in getting us what we needed in order to light this movie the way Janusz wanted to. If he wanted to power 10 or 11 18Ks through some windows, Paskal supported us by being flexible. At the same time, you can’t just say, ‘We’ll pre-rig the hell out of it so we’re ready for anything,’ because that can spiral out of control very quickly. Usually, we have two rigging crews, one laying down cable and one picking up, but if there’s a hiccup in the schedule — like when Leo got sick for two days — it’s all too easy to end up with six crews instead of two. I always have a detailed plan in place that allows us to track these hiccups when they occur. When we work with Janusz, Jim and I get the same amount of prep that he does, and we spend a lot of it on technical budgeting.

Dubin: Steven’s preference for working fast gives the camera crew a lot of responsibility. We’re often like one of the actors, in that when Steven says, ‘Action,’ we all have to perform on cue without any mistakes. On this film, we rarely rehearsed a shot. In fact, there was the unwritten 30-second rule: if someone asked for a rehearsal and it didn’t happen in the next 30 seconds, then inevitably someone would say, ‘Let’s just shoot the rehearsal.’ It was great fun, and fortunately first assistants Steve Meizler and Mark Spath and second assistant Tom Jordan were all up to the challenge.

How did the fact that you’d worked together so often affect the filmmaking process?

Devlin: We all feed off each other. This is also the tenth film I’ve done with Jim Kwiatkowski. When we go into a shot, we all have ideas about how Steven will want it covered. Jimmy will even have options ready for the camera that he hasn’t discussed with Steven or Janusz! What helps make this all work is that Jimmy and I have our own pre-rigging crews who are also supporting and anticipating us. Steven and Janusz went well out of their way to make sure that Brian Lukas, my rigging gaffer, and Charley Gilleran, Jim’s rigging grip, and best boys Larry Richardson and Kevin Erb were brought onto this show. Janusz knows that the quality of the cinematography starts with the crew.

Dubin: What’s great about having the same crew on all of these movies is that we all have a shorthand. When you go on the set of one of Steven’s movies, it seems like total chaos — it’s so loud because everyone’s screaming and everything’s happening at once. It can only happen that way because we all know each other so well. By now we all have a feel for Steven’s visual style and we’re able to implement it, but the great thing about him is that he always pulls something new out of his hat.

Can you give us an example?

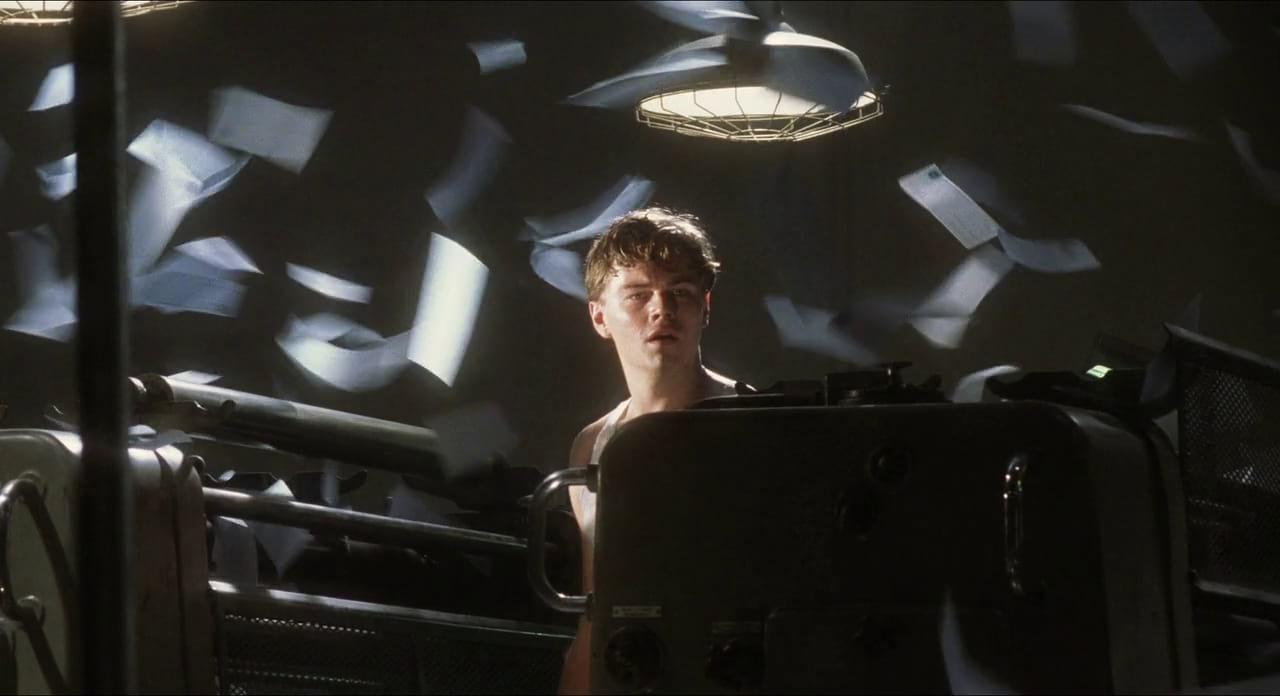

Kamiński: This film has a complicated shot that covers a five-story apartment building at night. As the camera pushes toward the building, we see little dramatic vignettes happening in each of the building’s windows — we see people having dinner, people fighting, people making out, and finally we come to Leo sitting at a desk at his window. Of course, he’s forging checks.

Dubin: We didn’t have quite the right set of equipment to facilitate the move Steven wanted to do. The camera needed to be quite nimble and move all over the building’s exterior, but what we ended up using was a 60-foot crane and a Wescam XR remote head. A crane moves in an arc, and Steven wanted to move more in right angles. It was very difficult to do. You’re always trying your best to making everything perfect when you’re behind the camera, but there’s always something slightly out of place or something that’s not exactly how you want it. Steven knows that the trick to working behind the camera is the art of compromise; he knows when the compromise is acceptable and when it isn’t.

How did you light that shot?

Kamiński: You don’t want to light the façade of the building too much, especially if you have illuminated windows; you just want a little bounce light from the ground. I approached the windows the same way I would if I was lighting an individual apartment – I just did it for 20 of them.

Devlin: On the day of the shoot I didn’t have a clear idea of exactly what we’d be seeing, and when we started looking at it I got the creeping suspicion that I was far from ready! We ended up lighting 15 to 20 windows, and I only had five electricians, and two of them were in Condors. That’s when I usually get the fight-or-flight syndrome: I run around, grab whatever I can from our lighthead carts and start hustling them up to those rooms with whoever I can muster. We tried to give each room its own look — some were fluorescent-lit, others were lit by a tungsten table lamp, and others by a glowing TV set.

Once the actors rehearsed it, we made adjustments to fit the action, but because Steven shoots so quickly people tend to end up where they shouldn’t necessarily be when the cameras roll. It can be very nerve-wracking when someone’s got to get in there, make an adjustment and bolt out. Dan Windels, one of the electricians who’s been with me for years, has great patience for lighting and is a lot easier to hide than Marek Bojsza, who’s 6-foot-5! On A.I., we were doing a wide shot in a bedroom, and after each take Dan would come out from under the bed, tweak a light and then crawl back under. In the difficult tracking shot we’re talking about now, Dan’s crouching under the table that Leo is using, or he’s hidden in a bathtub! He’s a great sport, and this was one of those days where patience like his really paid off.

Dubin: There’s another complicated move we knew about well in advance – it’s actually the reason we had the 60-foot crane and Wescam XR head on set. The shot shows Frank walking down a New York street wearing his pilot’s uniform and white hat, and he’s amid a sea of people in dark suits. The camera starts very, very high and moves down the street with the whole mass of people, then it drops down and pushes into the back of Frank’s head until his white hat is filling the frame. The difficulty was that so many people had to be in perfect sync: five or six of us, including Jerry Bertolami on the crane arm and Stevie Meizler pulling focus, had to function together to do this one shot, and we had to work with the movement of Leo and all the extras. That’s where you see the payoff from all of us having worked together so much. We actually got the shot in just a few takes.

Given that Abagnale is a forger, several key scenes take place in banks. How did you approach those scenes?

Kamiński: Steven and I came up with this idea that banks are the churches of the modern world, especially those banks built in the early 1930s — they literally look like temples, with huge windows and balconies. We wanted to create a sort of ‘divine’ lighting to support this parallel. We shot in an amazing bank in Brooklyn that we lit almost entirely with Muscos. The bank had huge, cathedral-like windows that hadn’t been washed in over 50 years, so we needed a lot of light. It was very expensive but it did the job. We didn’t have to bring any major lights inside.

Devlin: It was fun to walk into that huge bank and see five huge windows and say, ‘We’re going to need five Musco lights.’ The producers thought I was kidding at first, but it didn’t make sense to move lights like that around because we could easily see all the windows in one shot. On the day of the shoot, if we’re not ready to fulfill this story point for Steven, then why are we there? He really wanted to see the whole place.

We had some Seven-Minute Drills in there, but you can often lose the magic if you start filling it in too much. The Muscos lit the set, and the wide shots will look great because there’s a bit of atmosphere and you can see our ‘sun’ coming through it. But what really makes that scene is much subtler: there’s a shot of Abagnale coming up to the teller window to submit a forged check, and there’s a backlight on the bars of the teller window that Janusz rushed to add after the third take. It was probably a Tweenie gelled with full blue because we didn’t have an HMI handy; it perfectly highlighted the bars and the forged check.

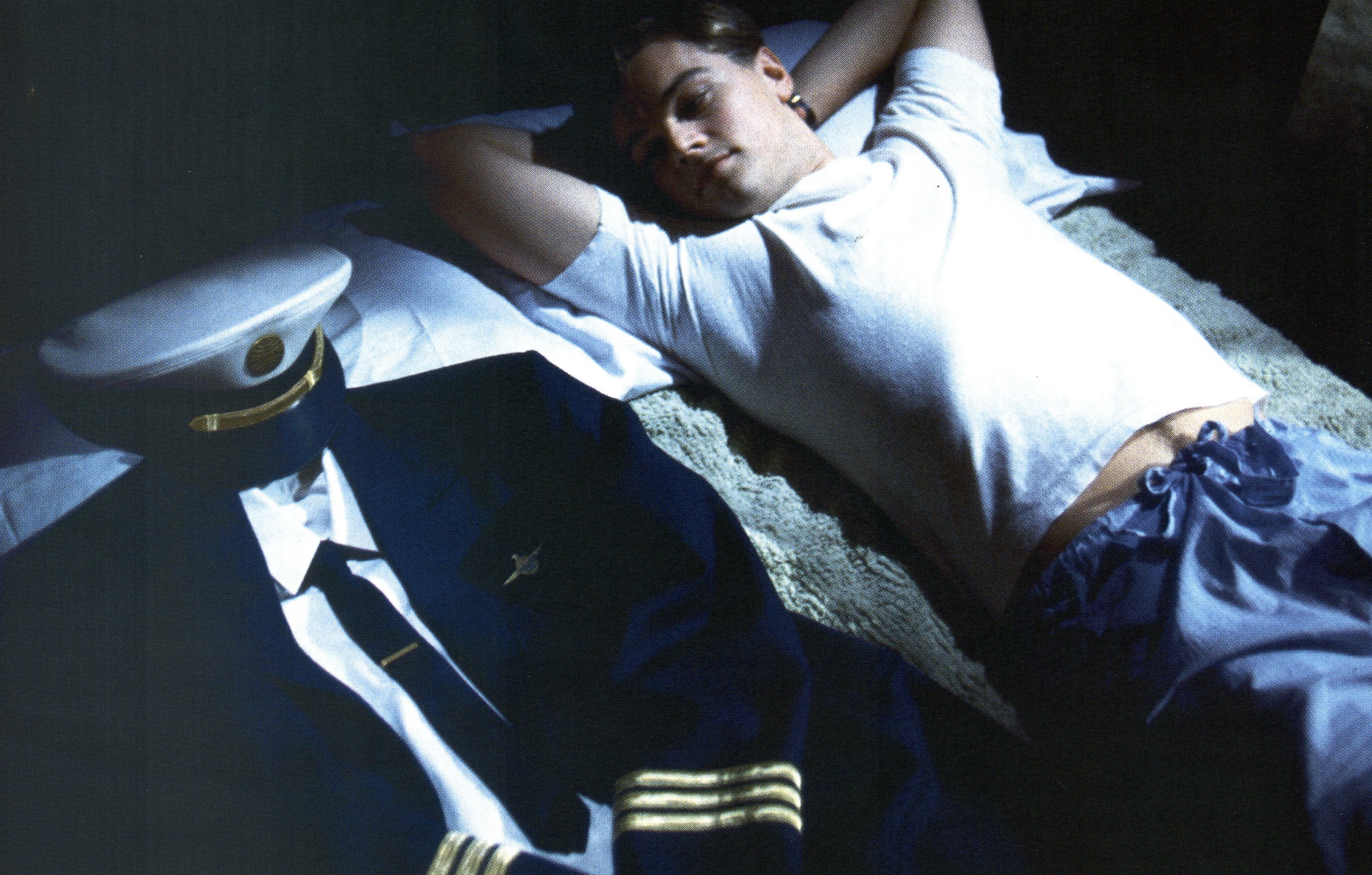

Throughout the film, Abagnale travels around the world impersonating an airline pilot. How did you approach the filming of airplane interiors?

Dubin: It’s very difficult to get the camera in the right place in an airplane. Even if it’s a set, you’re dealing with one aisle, and the camera takes up a lot of space. When Leo was sitting in a window seat, it was almost impossible to get the camera in a place that approximated his point of view. We ended up using longer lenses in those scenes than Steven normally likes to use.

Devlin: We had a lot of plane scenes in Jerry Maguire, and Janusz and I used the same approach to lighting the plane scenes in this film. In order to create a good amount of soft, ambient light to crisscross through all the little apertures a flying plane gives through its windows, you have to use a lot of point sources. We lined up 44 16-light Fays on the ground on each side of the plane, as many as we could, end to end. This gave us a wash of diffused light coming through the windows that’s very even and rather bright. From above we suspended LumaPanels to create some blue toplight through the windows. LumaPanels are 4-by-7-foot fluorescent fixtures balanced to 3200°K, and we gelled them with quarter CTB.

Creating convincing hard sunlight coming into the cabin of a plane for a wide shot is rather difficult because you can never place your source far enough away yet still have it be bright enough. We had three Dinos on dimmers, and Jim Kwiatkowski put them on a skateboard-dolly track so they’d move along the side of the frame. We used wide-beam 3200°K bulbs in them to get a bit more spread, and they’re less powerful. Even though it’s not logically correct to have multiple sources, it worked well because it created a creeping sunlight that moved along to simulate the movement of the airplane.

For scenes with Leo in the cockpit, we used a 20K beam projector on a Titan crane to act as the sunlight moving across the interior of the cockpit. If you need just a wash of ambient light, a 20K Fresnel works great; to make it harder and stronger, the beam projector is the way to go. To facilitate very specific movement, we had ours mounted on a head so we could pan and tilt the light. It’s really the best way to do it, because as the shot changes you can just move the Titan painlessly. It’s not even that expensive.

TECHNICAL SPECS

1.85:1

Panavision cameras

Zeiss lenses

Kodak Vision 320T 5277