Caught: A Lost Noir Classic

Legendary director Max Ophuls and accomplished cinematographer Lee Garmes, ASC lent their skills to a widely-scorned 1949 picture that has proven its worth over time.

This article originally appeared in AC May 1998

After Adolph Hitler rose to power in Germany, many distinguished filmmakers fled the country. One was Max Ophuls, an important director in both Germany and France, who struggled to gain a Hollywood foothold after emigrating to America in 1941. Ophuls survived numerous minor, anonymous jobs and a traumatic experience trying unsuccessfully to write and direct Vendetta for Howard Hughes and Preston Sturges. He then directed four American pictures: The Exile and Letter From an Unknown Woman (both 1947), Caught (1949) and The Reckless Moment (1950): though all were excellent pictures, none achieved financial success.

Enterprise Productions, Inc., which produced Caught, was established in 1946 by veteran production executives David L. Loew and Charles Einfeld to provide a home for exceptional independent projects. As defined by famed lexicographer Noah Webster, their slogan could be denoted as follows: Enterprise (noun): 1. An undertaking, especially one which involves activity, courage, energy. 2. An important or daring project.

With capitalization of $5 million, a $10 million credit line, and a releasing deal with United Artists, the company leased Harry Sherman's California Studios, which was then a decaying Hollywood facility dating from 1916. (Today, the site is home to the ultra-modern Raleigh Studios on Melrose Avenue.) Sherman had once produced Paramount's Zane Grey and Hopalong Cassidy films at California.

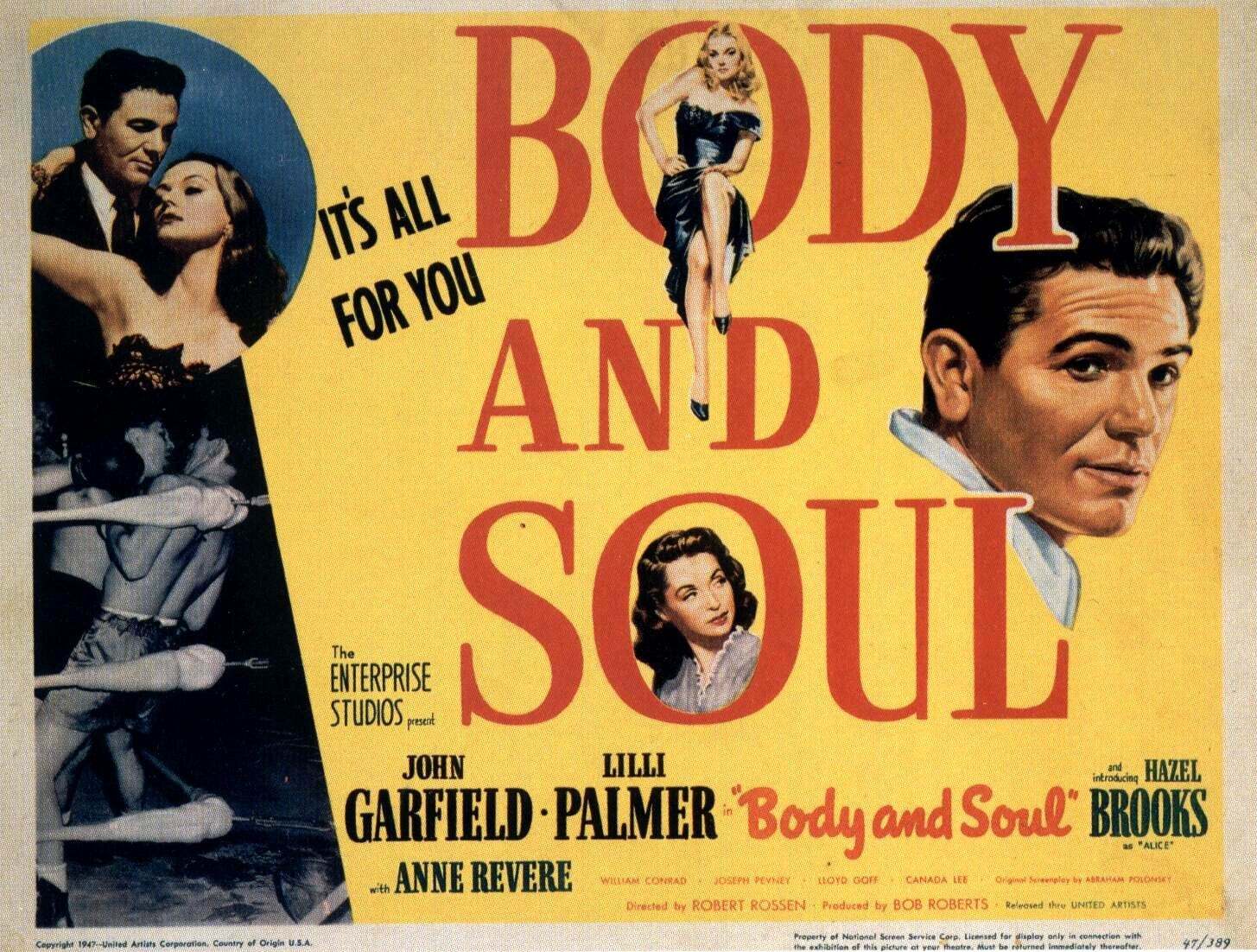

Enterprise's initial advertising listed five pending productions: Ramrod, The Other Love, Arch of Triumph, Body and Soul and Wild Calendar. While these and other projects reached the screen as distinguished pictures, only Body and Soul became a financial success.

Wild Calendar, the working title of Caught, was a novel by Libbie Block that was purchased in 1946 as a starring vehicle for Ginger Rogers. The tome concerns the unhappy marriage of Maud, a Denver girl, to a wealthy but ruthless cousin, Smith Ohlrig. While most of the Enterprise pictures were made in association with outside independent producers, Wild Calendar was to be produced solely by Enterprise on a hefty $2.5 million budget.

Kathryn Scola spent most of the second half of 1946 writing a screenplay that was subsequently turned down by both Rogers and the MPPDA censorship office. Abraham Polonsky then spent six months doctoring the script, smoothing out material that had been deemed objectionable. Several other writers later worked on the screenplay as well, but Rogers found none of their efforts acceptable, and walked off the project in December of 1947. In the meantime, censor Joseph Breen remained miffed about the script's inclusion of a "strange" relationship involving Ohlrig's brother.

On March 29, 1948, Ophuls came aboard and began working on an entirely new script with Paul Trivers. His disdain for Howard Hughes and Preston Sturges manifested itself in the character of Ohlrig, whom he gleefully invested with both men's least attractive traits. Einfeld, however, threw out the Ophuls/Trivers script, and on May 31 hired Broadway playwright Arthur Laurentz to create another version, which omitted Ohlrig's brother entirely. Meanwhile, Letter From an Unknown Woman, Ophuls' directorial effort for Universal-International, opened at theaters, only to vanish soon after an artistic achievement that bombed at the box office.

Repeated production delays pushed back Caught's schedule while other pictures filled the breach. By the time of the film's planned start date, most of the studio's assets were tied up in what was expected to be its biggest hit: Arch of Triumph starring Ingrid Bergman, Charles Boyer and Charles Laughton. Advertised as "the most distinguished screen event of our time," it became a fiscal disaster which threatened Enterprise's very existence. Ending its connection with United Artists, Enterprise sealed a deal to release its coming program through MGM. Caught finally was scheduled to start shooting on July 8, under the supervision of MGM alumnus Wolfgang Reinhardt.

In the finished script, Denver carhop Maud Ames comes to New York, changes her name to Leonora Eames, and enrolls in charm school in the hope of becoming a model and marrying into money. She meets Smith Ohlrig, a handsome millionaire, who marries her just to spite his psychiatrist. A paranoid recluse subject to psychosomatic heart attacks, Ohlrig makes Leonora a virtual prisoner in his mansion; her only companion is an effeminate parasite named Franzi. Leonora flees and takes a job with the poor but dedicated Dr. Quinada. Ohlrig entices her back and makes love to her, but after he schedules a business trip, she returns to Quinada. Upon learning that she is pregnant, however, Leonara returns to Ohlrig once more. Quinada comes to take her away, but when Ohlrig demands custody of the child, she stays. For months, Ohlrig subjects her to mental torture. At last she rebels, and Ohlrig finally suffers a real heart attack. She deliberately walks off, leaving him to die. Quinada arrives to take her away and send Ohlrig to the hospital. Racked with remorse, Leonora miscarries, but nonetheless finds happiness with Quinada.

Ohlrig, played by Robert Ryan, was drawn from Howard Hughes, who therefore had script approval. Much to everyone's surprise, the tycoon asked only that Ohlrig be made to appear less obviously like himself no rumpled clothes or Texas background. A lean ex-pugilist who had become a leading player of heroic characters, Ryan was happy to score an offbeat role as a psychotic villain. Years later, Ryan told an audience at UCLA that "Howard knew all about it and even encouraged me to 'play him like a son of a bitch.'"

"Without a doubt, I think Max Ophuls was one of the greatest filmmakers we had. A sweet, sweet man, he got a very raw deal in Hollywood.

— Lee Garmes, ASC

Leonora, the story's central figure, was a difficult role to cast; she had to be pretty without being glamorous, and ambitious without being pushy. At the last moment, another Hughes contractee, Barbara Bel Geddes, was selected. The intellectual daughter of famed designer Norman Bel Geddes, she had to "dumb down" for the role, but proved to be the perfect choice.

Kirk Douglas had been announced for the role of Dr. Quinada, but delays in the starting date left him unavailable. In what was considered a major coup, the most popular actor in England, James Mason, ended up filling the physician's shoes. In addition to the opportunity to work in America, Enterprise's offer of $150,000 plus a percentage and first billing helped, plus the fact that Mason wanted to work with Ophuls. The Briton had another reason as well: his popularity which had lately spread to America was based on portrayals of Heathcliff-styled characters who were handsome and romantic, but cruelly domineering. Like many typecast actors, Mason eagerly accepted a wholly sympathetic part.

Ophuls reported to work on Monday, June 21, with a fever and body sores; he was suffering from herpes zoster (shingles). By the beginning of July, his condition remained unimproved, so the studio reluctantly terminated him.

His replacement was John Berry, an alumnus of Orson Welles' Mercury Theater who had previously directed four pictures. Berry's salary was more than twice the rate Ophuls had received, underscoring the plight of foreign talent at the American studios.

Teamed with Barry was Lee Garmes, ASC, the celebrated American cinematographer behind Zoo in Budapest (1933), which some connoisseurs rate as the finest black-and-white work extant (see AC April '95). Garmes had co-directed and shot seven notable pictures with Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, in addition to directing and/or producing several other films as well. He was a lover of the "north light" school of painting, and applied this technique to many of his own movies. For many directors, Garmes was a godsend one whose singular "touch" could make a good picture great.

Berry definitely did not want a collaborator, however. The director had strong ideas about cinematography and wanted them followed without question, right down to the choice of lenses.

The film's principal photography commenced on July 14 with Mason not yet committed (he signed a contract on July 28) and Ryan unavailable. Both Mason and Bel Geddes balked at working with Berry due to his unknown stature, but eventually relented and signed onto the film. Due to the production company's financial crisis, the budget was cut almost in half and the schedule trimmed to just 36 days, fewer than any other Enterprise project.

From the onset, Berry and Garmes argued incessantly. When Garmes made suggestions that he felt would improve a scene, Berry accused him of overstepping his bounds. (In fairness, several other directors had butted heads with Garmes for the same reason.) Robert Aldrich, the unit production manager and a longtime friend of the director, sided with Berry, further alienating Garmes. Scribe Laurentz, Garmes, executive production manager Joe Gilpin and especially executive producer Reinhardt were all disturbed because they saw that Berry intended to make a starkly realistic story about a tough gold-digger, instead of the romantic drama originally envisioned.

Berry actually filmed several sequences, including exteriors in Los Angeles and Pasadena, and scenes at a charm school with Bel Geddes, Frances Rafferty, Marcia Jones, Natalie Shaefer, and Sonia Darren. By the tenth day of production the director had fallen five days behind. Much to the shock of cast and crew, Reinhardt dismissed Berry and brought Ophuls back to the studio a few days later.

Aldrich claims that the producers had made a secret deal with Ophuls to fire Berry as soon as Ophuls could return to work, and that he "would guess that somewhere between a third and half of the film is Berry's." The American director received much more money than Ophuls because Enterprise continued his salary until the close of production, but Berry was denied screen credit.

As in most situations where a director assumes a picture begun by another, Ophuls wanted to reshoot all of Berry's work. Some scenes were written out by Ophuls and Laurenz; others, including the charm school sequence, remained because the new budget wouldn't permit them to be restaged. Rafferty, a former MGM starlet, originally had an important role as Bel Geddes' roommate, who commits suicide after becoming pregnant. This subplot was eliminated and Rafferty's name was dropped from the credits, although she still has dialogue in two scenes. Also excised were Marcia Jones' scenes as the second roommate; the two female characters were merged into one, played by Ruth Brady.

To Garmes' horror, the cameraman found that he had underexposed the Pasadena scenes badly; to minimize the error, he had the rushes printed on blue stock. Ophuls told him that the scenes were still very good, which became a moot point because the sequence was dropped during script revisions. The director and cinematographer soon became close friends, and worked together without friction. Garmes had brought with him an outstanding dolly grip, Morris Rosen, along with the original model of the superb crab dolly that Garmes, Rosen and Steve Krilanovich had designed for Alfred Hitchcock's The Paradine Case. The contraption was kept very busy in Caught, due to Ophuls' fondness for long takes with unusual camera moves. There was an inside joke that "Max would go nuts" if deprived of big sets, dollies and cranes; at the same time, the picture is full of the type of locked-down, artistically-composed shots for which Garmes is noted.

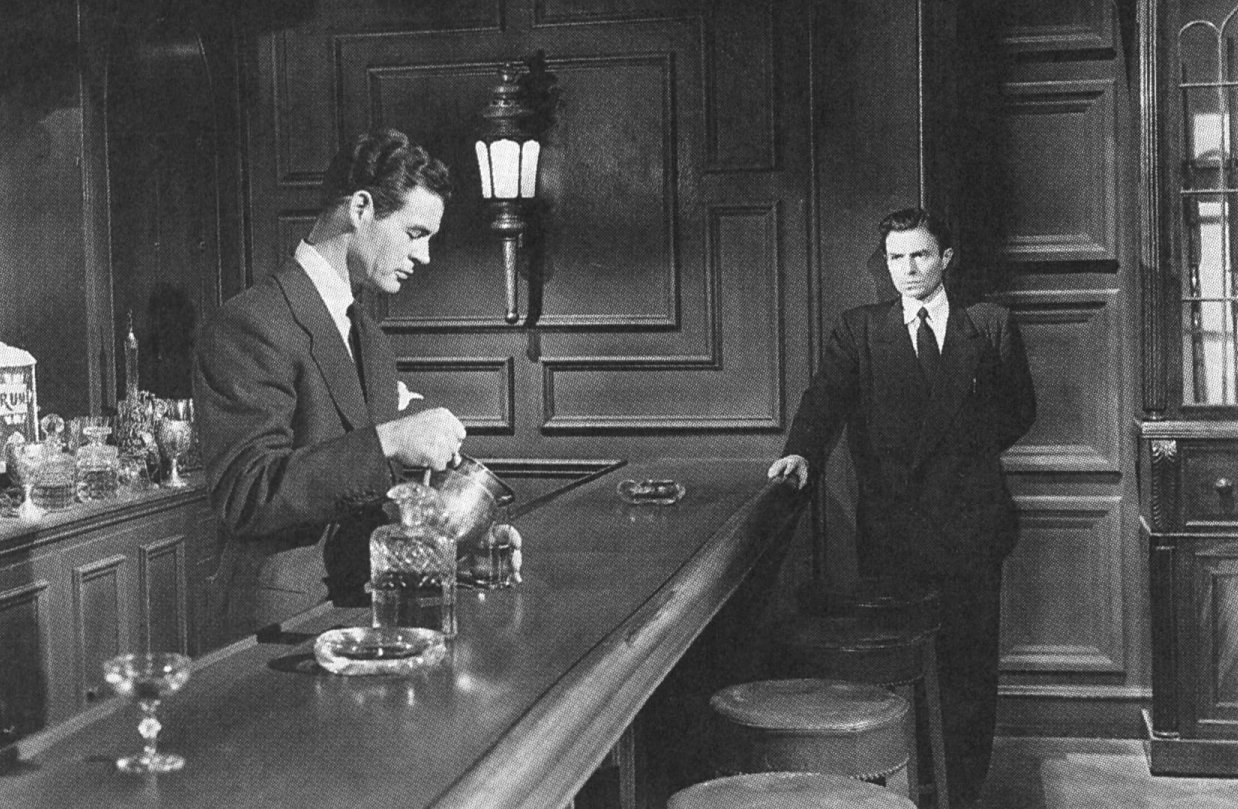

The most impressive set and the setting of the film's major dramatic confrontations was Ohlrig's huge game room, built in California Studios' cavernous Stage 5. One wall was lined with a row of windows extending some 40' to the ceiling. Despite these expansive panes, the room remained dark, with practical sources such as a fireplace, lamps and chandeliers providing localized illumination. The single wild wall was behind the bar, the area where most of the action took place. The camera made numerous moves in this room, traveling without tracks over the smooth floor. Many scenes, such as the confrontation between Ohlrig and Quinada standing at opposite ends of the bar of the game room, were staged for depth in the manner of Citizen Kane.

The extended sequence of Ohlrig's "fatal" heart attack near the end of the film is particularly notable, both photographically and for Ryan's virtuoso acting. The striking shot is composed in deep focus, with the top of the bar in the foreground and Ryan some distance away when he's hit by the seizure. He lurches toward the camera, zig-zagging erratically as he fumbles for the life-saving pills in his pocket. The camera follows him closely, with the moves becoming increasingly violent as he arrives close to the camera and scrabbles desperately for liquid to help him down the pills. He finds an ice bucket, dumps meltwater into a glass, gulps it down and gasps for air. Ryan achieved the harrowing effect by holding his breath throughout the torturous walk.

Upon hearing Ohlrig's cries, Leonara comes downstairs to find him lying on the floor, partially obscured under an overturned pinball machine. The camera views the scene from floor level, with the hard-lit Ohlrig lying on his back close to camera, begging Leonora, who's seen full-figure in a white nightgown, to call a doctor. She watches dispassionately before turning away and ascending the stairs.

Another tricky sequence, in terms of both lighting and camera moves, reveals Ohlrig screening movies of a new project to his associates. Leonora giggles at a whispered comment by Gentry (Wilton Graff), whereupon Ohlrig halts the screening. After furiously accusing the two of laughing at him, he orders the man to leave. When Leonora walks out, Ohlrig angrily dismisses everyone. This is technically an intricate scene, reminiscent of the screening-room opening of Citizen Kane, with a large dark room fitfully illuminated by the flickering light of a film projector. Garmes used a wide-angle lens to emphasize Ohlrig's dominant bulk in the foreground and Leonora's minute size in the lower part of the frame. After an unusual reverse angle in which the close and distant figures are placed in the same positions (with the close figure at left in both angles), the camera returns to the first angle. As Leonora leaves, the dolly moves left while the camera pans right to follow her.

Another enormous set was the two-story main hall of the mansion, with its massive pillars and high, curving staircase; the dolly was brought into play for long takes in this space as well.

Contrasting such opulence were scenes within Leonora's rented rooms, which are cramped and dark; accenting these spaces are patches of bright light under mazda lamps, which lend the sequences a noir atmosphere. As Leonora discusses her dreams of wealth, she toys with a flyswatter, the shadow of which moves back and forth ominously across her face. Even Leonora's large bedroom in the mansion is made claustrophobic by heavy shadows above the bed, which fill much of the frame. For several scenes in the doctors' offices and waiting room, the filmmakers utilize a technique traditionally associated with British director James Whale: the camera moves parallel to the action, past walls or seemingly through them.

Enterprise Productions was rapidly running out of money, so much to Ophuls' chagrin, the notion of reshooting any of Berry's additional footage became financially impractical. Retakes also had to be held to a minimum, and further set construction was curtailed. Garmes, thanks to his work with Hecht and MacArthur, was experienced at improvising fragmentary sets and making them look decent; he had created the nightclub set for Crime Without Passion, for example, out of a few tables, some chairs and well-placed shadow-play. Art director Frank Sylos possessed similar abilities, since he was an alumnus of the most penurious of studios: PRC. For one Caught sequence that transpires in a crowded bar, large bottles and glasses in the foreground and the movement of extras in the background cover the set's simplicity. On the dance floor, the camera stays close to Leonora and Quinada usually above eye-level with the heads and shoulders of other dancers filling out the frame; fragmentary glimpses of the "set" are of a wild wall and some black scrim. This scenario was shot hurriedly in long takes, with the actors indulging in some improvisational dialogue.

Another effective makeshift setting is the fog-shrouded dock where Leonora first meets Ohlrig. A portion of the dock was constructed on a stage backed by black velvet, with the approaching motorboat's light represented by a bobbing spotlight offscreen. Coupling this source with an overhead dock light created shafts in the fog that provided the lonely girl with dramatic illumination. Elsewhere in the film, Quinada and Leonora meet secretly in a garage that adjoins the mansion; this car stall was actually a building on the lot which was dressed up by the placement of some expensive vehicles within it.

As Ohlrig, Ryan is seen mostly from below eye-level often via wide-angle lenses to create the impression that he is taller and more powerful than the other players, and to grant him an angularity which symbolizes his warped mind. Conversely, Mason's Dr. Quinada was photographed mostly at eye level with lenses of 50mm or longer.

"Without a doubt, I think Max Ophuls was one of the greatest filmmakers we had," Garmes said when interviewed by David Prince, Peter Lehman and Tom Clark in Wide Angle (Vol. 1, No. 3). "A sweet, sweet man, he got a very raw deal in Hollywood. But if you look at Caught you'll feel that the camera was looking through a crack of a window or a crack of a door, or that the camera was never placed in a spot in the whole picture that was conventional, like most directors do. He has a wonderful knack for saving his scenes and saying, 'I think it would be nice to do it from here.' And we'd do it from there."

Caught wrapped on October 5, two days after Enterprise relinquished the studio to Harry Sherman. The negative cost was $1,574,422, including retakes and two days' worth of studio rent. Although a far cry from the originally earmarked $2.5 million, the reduced budget still constituted a major expense for the rapidly crumbling company.

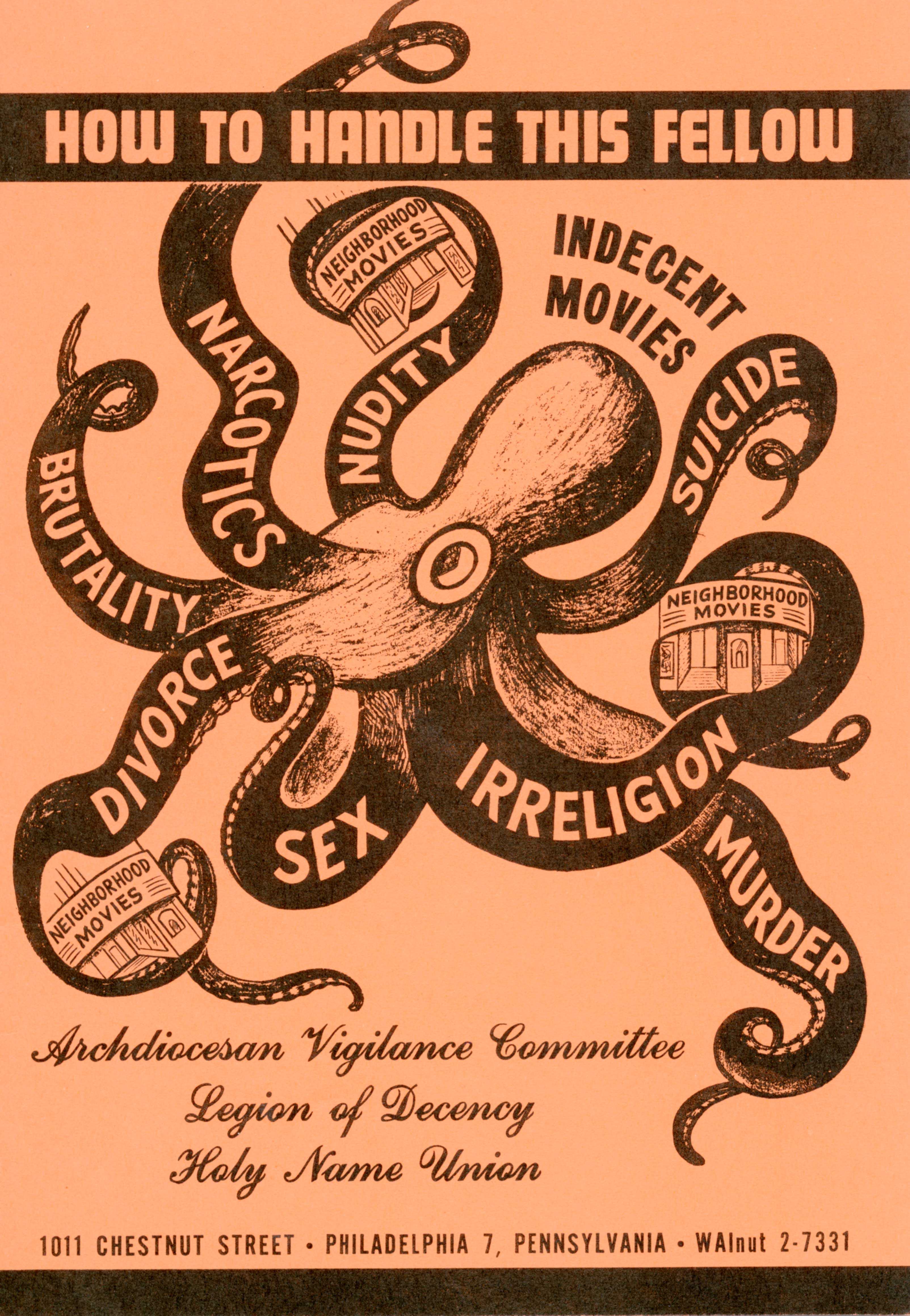

Having seemingly placated the censors during production, MGM was surprised after a New York screening to receive word from the National Legion of Decency, a powerful Catholic organization, that Caught was slated to be stamped with their dreaded "C" rating: Condemned. Theaters which showed "C" pictures were deemed off-limits to all Catholics in the United States. The picture was called "a clear-cut plea for the acceptability and justification of divorce" a judgment exacerbated by the ending, which made it clear that Ohlrig's heart attack was not fatal but that Leonora and Quinada would soon marry.

The NLD withdrew its threat after MGM and Enterprise agreed to remove the dialogue indicating Ohlrig's recovery, so that audiences would assume that he had died thus leaving Leonora free to marry Quinada. (The currently available Republic videotape retains the original dialogue, which was replaced by Bob Gitt of UCLA's film restoration program in 1988.)

A sneak preview of the picture held at Pasadena's Alexander Theater yielded enthusiastic report cards; impressed executives decided against any further previews or revisions to the film, and hopes arose of Enterprise's imminent financial recovery.

The bubble burst, however, when the picture, given little fanfare by MGM, opened in New York to sparse audiences and hostile critics. The London opening, despite Mason's popularity there, also suffered a frigid reception. Though Mason's American film debut had been eagerly awaited, fans were disappointed by his comparatively colorless role, however well-played it may have been. In rather acerbic British fashion, the Daily Mail reported, "It will be particularly depressing to women who have come to regard an annual vicarious beating from Mr. Mason as essential to a full and happy life."

And so Enterprise, a noble but doomed concept, sank out of sight, while Caught, branded as one of the reasons for its demise, drowned along with it. Ophuls returned to France and attained new glory there, but before his death in 1957 he was in the midst of a desperate attempt to procure a contract with an American studio.

A curious thing about movies is that yesterday's failures occasionally become modern classics. Such is the case with Caught. Today's audiences would not be off-put because Mason chose to deviate from his patented portrayal of romantic evil, that Bel Geddes wasn't a glamour-puss, or that Ryan portrayed a psychopath. The pleasure of watching performers acting against type, the subtleties of Ophuls' direction, the artistry of Garmes' cinematography, the richness of Frederick Hollander's Continental-styled music all of which went largely unsung in 1949 have proven to be of greater lasting importance than whatever fads prevailed a half-century ago.

If you enjoy retrospective and archival coverage of classic films, you'll find much more here. And for complete access to every issue of American Cinematographer since 1920, subscribe here.