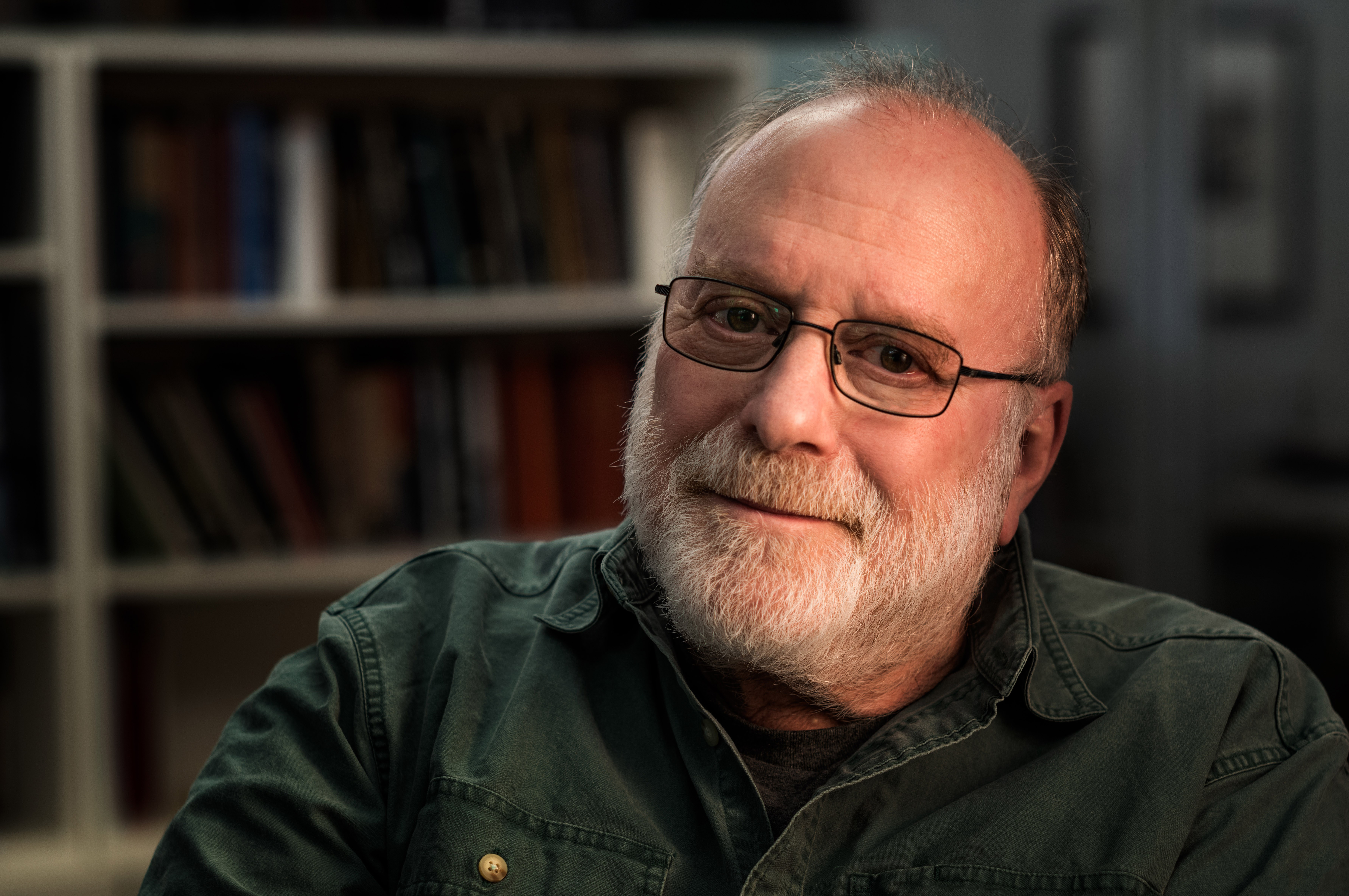

Charlie Lieberman, ASC: A Promise Fulfilled

The Society honors one of its most dedicated and active members with the Presidents Award.

Before any cinematographer is invited into the ASC, they must sit for an interview with the Society’s Membership Committee, which is open to all active members for participation. Many of the Committee’s questions explore the candidate’s technical acumen, inspirations and creative process, but others are designed to assess character, as well as how the candidate’s membership might benefit the Society.

When the Membership Committee asked ASC candidate Charlie Lieberman how he could help the organization, he was stumped. “What on Earth could I do to help them?” he recalls thinking at the time. “Me? I was possibly joining an organization of all my heroes — artists who had inspired me since I was just a kid at the movies, long before I really knew what a cinematographer was or did. I felt I was going to be lucky to just be in the room.”

But Lieberman vowed to volunteer when needed, and he has done so ever since. Indeed, for his ongoing service to the Society — on multiple fronts — he was recognized with the 2023 Presidents Award during the 37th Annual ASC Awards on March 5.

Early Approaches

Lieberman grew up in Chicago in the 1950s, and going to the movies was a favorite pastime. “The first I remember seeing was King Kong [1933], and I couldn’t have been more than 6. I completely believed every minute of it, except that I thought Kong moved a little funny. But I totally bought into the story. I think at some later point in my life, I came to realize that all films are a fiction in one way or another; even in documentaries, there’s a viewpoint involved in the storytelling decisions being made. I had no idea as a child, or even a young adult, that I’d end up working as a cinematographer in Hollywood, but it just worked out that way, and my whole path started with watching that film.”

As Lieberman’s interest in creating his own images developed, his older sister Maggie was a major supporter. “She was an artist — a sculptor and painter who clearly had talent even as a child,” he remembers. He taught himself the basics of photography, “and when I was in my 20s, I got the idea that I wanted to see if I had an eye for it, so I dedicated all my spare time to shooting what I later knew as ‘street photography.’ And I gave myself a year to take one good picture. My sister encouraged all of that. Finally, I got what I thought was a good photo — though now I think it’s pretty lame!” The process, however, encouraged him to persist.

“I can’t tell you how grateful I am for the opportunities I’ve had to do these things with the Society, and I encourage all members to volunteer their time, to give back in some way.”

One of Lieberman’s first professional assignments was to photograph Indigenous cultures in small villages across 14 countries for a series of anthropology books. One project led to another. “A documentary filmmaker saw some of these photos hanging in a bar in Chicago and hired me to shoot production stills on an anti-drug documentary starring Olympic gold medalists. He ended up incorporating them into the film itself. He didn’t tell me he’d done this, and invited me over to see a cut of the project. I was incredibly surprised, and those became the first images I ever contributed to a motion picture.”

That inspired Lieberman to pursue filmmaking, “and I started watching films more closely, trying to learn, and probably the people who affected me the most were [ASC members] Owen Roizman, Conrad Hall and Gordon Willis. I started to search for their names in the ads for movies that were playing so I could see more of their work. I didn’t care if the reviews of the films were negative; every movie of theirs was an opportunity to learn something. I didn’t go to film school, so only later did I start looking back and discovering [ASC members] Stanley Cortez, Russell Metty, Phil Lathrop, Gregg Toland and so many others who did great work and became major heroes.

“I learned on the job. I started in stills and was fortunate to work for companies that began to branch out and shoot films. Their clients started asking for motion pictures, and I happened to be there. My goal was to pay attention, do what I did well, and teach myself anything I could to advance — as well as keep food on the table.

“Before I started thinking seriously about becoming a narrative cinematographer — which followed many years of working on documentary, educational and industrial projects for local businesses in Chicago — I never thought my work would ever be seen by anybody outside a certain circle. My biggest audience was probably third-graders and businessmen!”

While the technical aspects of cinematography were something Lieberman could learn — often through trial and error — the confidence demanded by the position was another matter. “Early on, shooting a documentary, I was nervous about everything and worried I wasn’t remembering my light-meter readings correctly, so I kept checking over and over again,” he says. “The director noticed this and quietly said to me, ‘That’s not a good look. You can be nervous, but you can’t act nervous.’”

Film and Television

Lieberman’s big break came in 1985, when he was asked to shoot the indie horror feature Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. Loosely based on true events, the project was just two weeks out from shooting in Chicago when the original cinematographer dropped out. “I was recommended to the producers, and I brought a 16mm projector and one of my narrative-style educational films to screen at our initial meeting — I didn’t even have a reel!” Lieberman says. “But I got the job. And after reading the script, I realized that their original shooting approach — handheld, docustyle — wasn’t right. The script was written as straight drama, suggesting an objective, ‘fly-on-the-wall’ style. The director accepted my concept, so the entire visual approach was changed to go in a much more subtle direction.

“Working on such a low budget, every scene became a question of how we could create suspense and suggest horror because we couldn’t afford to show it. For example, in one scene, a character is murdered in a horrible way, and not only could we not afford elaborate makeup effects, but we couldn’t even use fake blood because we only had one costume available for the actor, so getting blood on it would have been a problem. That forced us to be very creative, and the result is a series of visual sleight-of-hand tricks — in concert with the audio — so audiences think they see much more than is really onscreen.” Completed in 1986, Henry was released theatrically in 1990, became a cult hit, and is now considered a classic of the genre.

Lieberman stayed in Chicago until 1989, primarily shooting commercials, and then relocated to Los Angeles. An early success there was shooting the Oscar-winning 1991 short film Session Man. He subsequently photographed such features as South Central, Love Is a Gun and Red Meat, as well as TV series that included My So-Called Life, Joan of Arcadia and Once and Again. He then joined the production team behind the hit superhero series Heroes.

Powered by compelling stories and one of the highest per-episode budgets of any weekly network series at the time, Heroes was a complex production involving multiple plot lines, a wide cast of characters and ambitious visual effects. “It was a show I didn’t know I could shoot until I was actually doing it,” says Lieberman, who photographed 27 episodes of the series, alternating with soon-to-become ASC member Nathaniel Goodman. “It was the apex of my career. My skill level at that time allowed me to really contribute something that could work well in the collaborative process of making the best show possible. It was also the most fun I ever had! Seeing it all come together at the end, with the editing, sound and music; seeing that the performances all worked; and seeing how my contribution worked with all of those elements in the storytelling was, to me, miraculous.”

Centennial Salute

In late 2008, Lieberman was invited to join the ASC after being recommended by Adam Kane, Dennis L. Smith and Steven B. Poster — and officially welcomed by then-ASC President Daryn Okada. “Becoming a member came with an incredible feeling of belonging,” Lieberman recalls, “but it took time for me to understand how the organization worked and figure out how I could participate within it, in part because I was an outsider. I came to L.A. from Chicago, and I had never worked as an assistant or operator for anyone — I didn’t have those roots. But I found my way.”

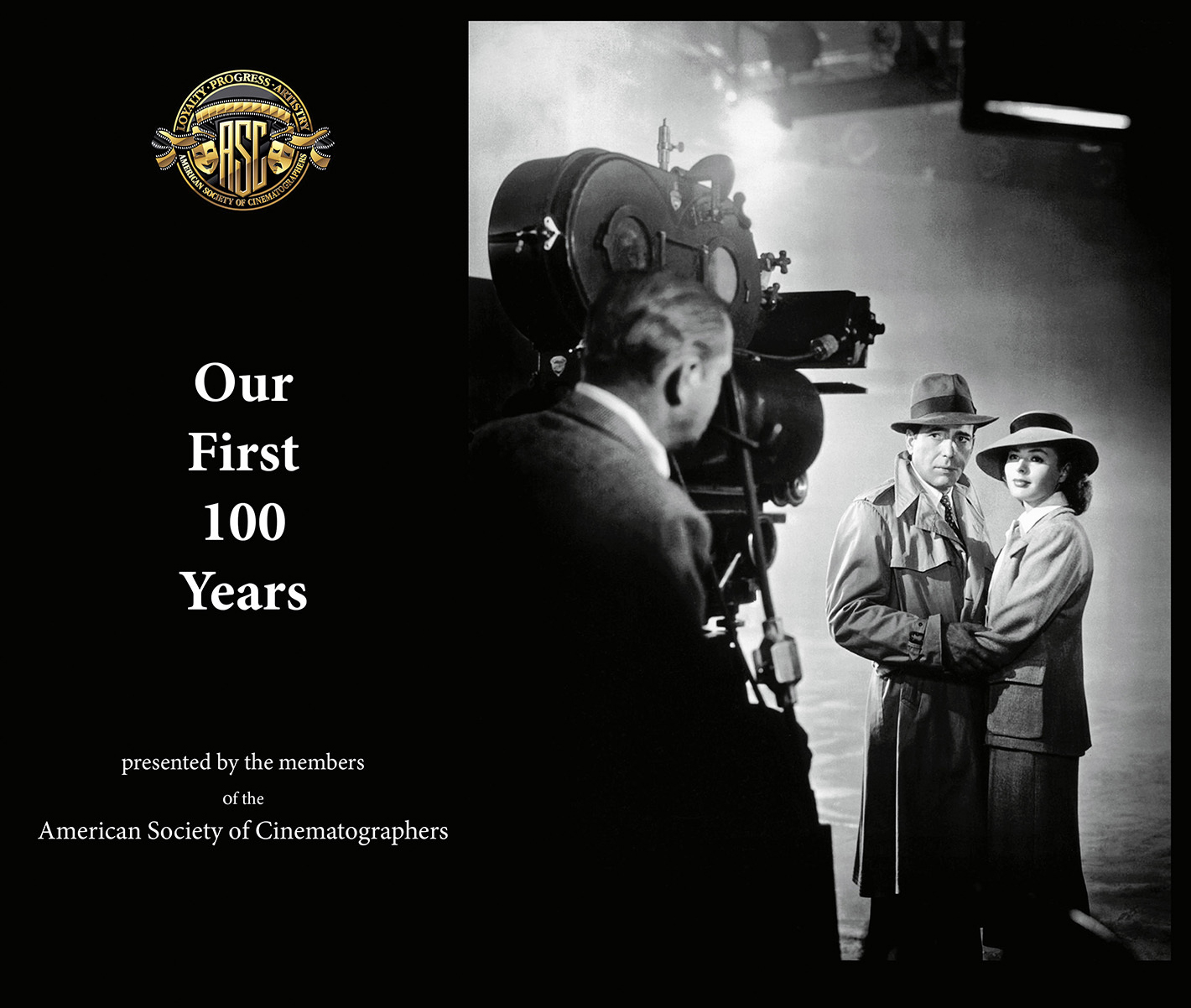

To help celebrate the ASC’s centennial in 2019, Lieberman supervised the design and publication of the book Our First 100 Years, showcasing the Society’s founders and documenting the inspiring careers and contributions of many of its members. “That process gave me an entirely new appreciation for our founders and the 1,000-some cinematographers who have been invited to join the Society since 1919,” he says. “They all have unique and inspiring stories, and helping to document all was wonderful to discover and share.”

In 2022, he coordinated the publication of an expanded second edition of the book, which also looks toward the ASC’s future — with the inclusion of the 50 new members invited into the Society since the first edition. “The effect is that we can learn from the past and also look forward to the future,” Lieberman says. “These new members, and those who follow them, will take the ASC well into its second century.”

Society Dedication

Lieberman currently serves on the ASC Board of Governors, and on a number of Society Committees — including as co-chair of the ASC Master Class Committee, with co-chair Michael Goi, ASC, ISC and chair Shelly Johnson, ASC. Lieberman participates in every session of the Master Class not only as an administrator but also as an instructor. His popular discussion session “The Political Minefield” delves into the intricacies of on-set collaboration and how this demanding profession impacts the personal lives of its practitioners. “My favorite thing about being an ASC member is the opportunity I’ve had in Master Class to mentor young people just starting their careers,” he says. “They need guidance and inspiration, and they look to the ASC and our members for that.”

As chair of the Constitution and Bylaws Committee, he helped coordinate the restructuring and modernization of the Society’s governance, portions of which were still geared to an entirely local membership working under studio contracts. Today, the Society has 446 active members working as independent contractors on every continent but Antarctica. “Working within the ASC’s established rules, we streamlined a variety of processes that govern the body, which will allow us to be more flexible to enact change when necessary,” says Lieberman.

The ASC’s Mentorship program, which pairs members with promising cinematographers around the world, has been another opportunity to give back: “My sister Maggie was my greatest supporter back in the beginning, but I never had a mentor, which is one of the reasons why I believe in and have dedicated time to the ASC’s program. Starting out, I never knew another cinematographer. I was on my own. Then, many years later, I met Owen Roizman, just before I was invited to join the ASC, and he gave me encouragement. I never got to know Owen well, but to have one of my idols offer that was hugely meaningful. I hope I can have that effect on someone who just needs encouragement.”

Connecting Through Images

Lieberman’s passion for still photography was rekindled when he retired from cinematography, and it has inspired a search for dramatic landscapes across the U.S. and as far afield as Iceland and India. “If I hadn’t found a way into motion pictures, I would have been a still photographer,” he says.

This interest led to the establishment of the ASC Photo Gallery Committee, which Lieberman chairs. Over the past few years, curated exhibitions of Society members’ stills have been shown at the Clubhouse, the Camerimage International Film Festival in Poland, and in other venues. “Overseeing the Photo Gallery has been very gratifying because it has allowed me to work closely with other ASC members to present their still-photography work,” says Lieberman, who, at the time of this writing, is assisting AC’s editorial team with assembling a new collection of ASC members’ images to be featured in next month’s issue. “In a selfish sense, this has been a way for me to meet so many other members — people whose cinematography I respect highly — and get to know another side of them. I only wish I had gotten more involved with the ASC sooner. I missed the opportunity to meet so many of the greats, like Vilmos Zsigmond, László Kovács and Connie Hall.

“I can’t tell you how grateful I am for the opportunities I’ve had to do these things with the Society, and I encourage all members to volunteer their time, to give back in some way. Being an active member of the ASC can be about so much more than just having those initials after your name. Receiving the President's Award for participating in things I’ve loved so much means more to me than you can imagine.”