Christopher Nolan on Oppenheimer

The director shares some of the cinematic strategies he pursued with cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema, ASC, FSF, NSC.

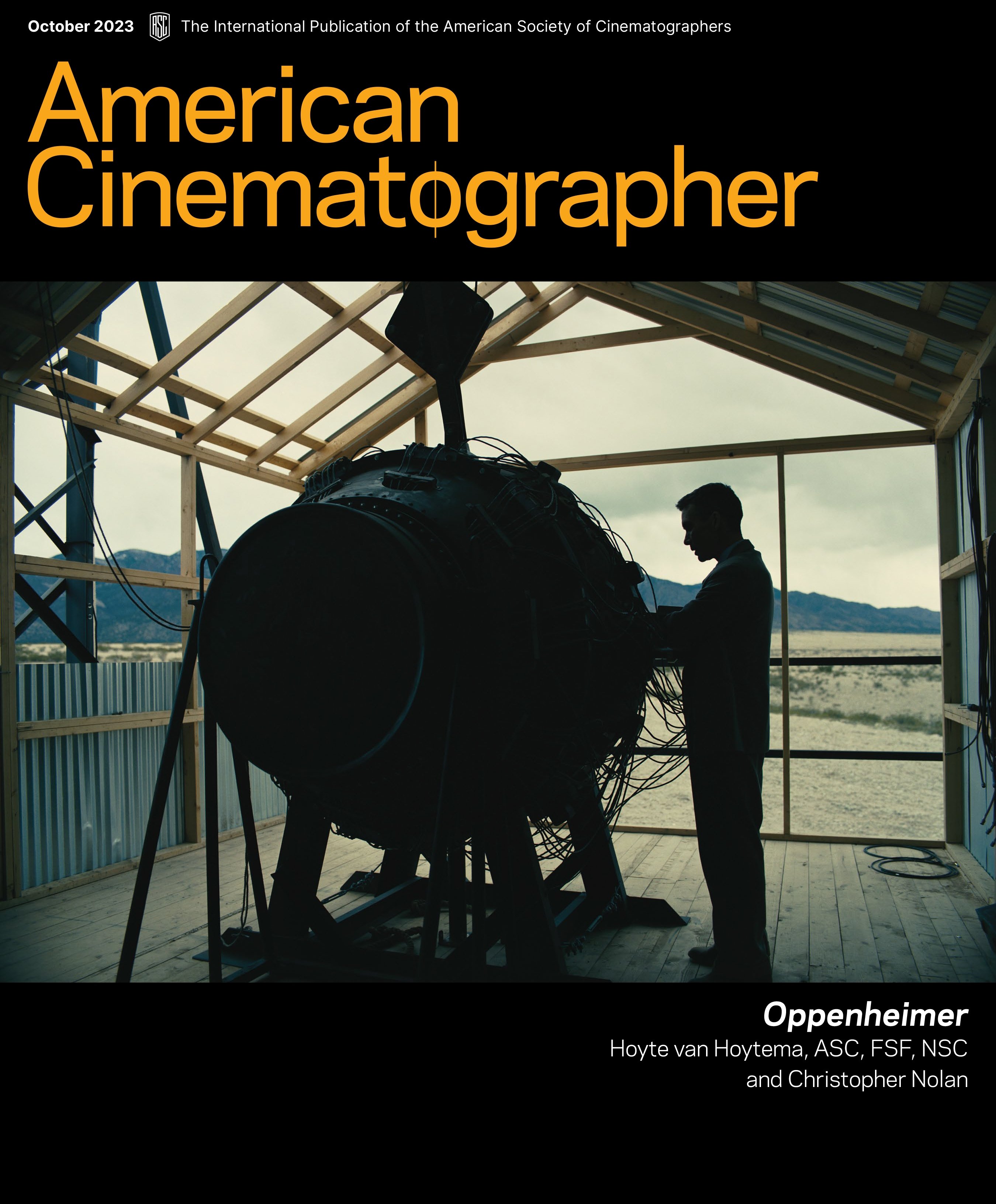

Photos by Melinda Sue Gordon, SMPSP; Courtesy of Universal Pictures

American Cinematographer: Your role as the director could be compared to the duties of Matt Damon’s character, Leslie Groves, in the film — he’s the man with the plan for this atomic program, but to make it a reality, he needs a team of scientists and dreamers. Is that a fair assessment?

Christopher Nolan: Leslie Groves was one of my main points of contact with the material, because it’s a little tough to relate to people like Robert Oppenheimer — who’s so smart, and who looks at the world in a different way than we do — but I could definitely relate to the challenge of putting together a team and building a project from the ground up.

How would you characterize your relationship to the key creatives on this film?

We needed every big creative mind on the film to work together. I try to keep everyone on the main team — Hoyte, [visual-effects supervisor] Andrew Jackson, [special-effects supervisor] Scott Fisher, production designer Ruth De Jong — close to me and close to each other, so that they’re talking with each other the whole time. I’m hearing what they’re saying, it’s firing my imagination, and I’m throwing ideas back at them. My job in all of this is to keep the conversation circulating and get the best out of everybody.

What can you tell us about Ruth De Jong’s contributions, relative to the cinematography?

Ruth had worked with Hoyte before, on Jordan Peele’s Nope, so they had a great ease of communication. And as we ran into the inevitable budget problems, we were able to look at the practical three-dimensional model of Los Alamos she had built. Hoyte could explain to her that when I said I’m only going to put the camera down a particular street, I would stick to that decision. So, she cleverly stripped that set down to the bare minimum that was needed to represent this whole town, and she and her team did an amazing job making something that was actually practical feel vast. It was a tremendous challenge, but they delivered the goods.

“The unique quality that Hoyte brings to photography is that he’s prepared to talk about an idea in abstract terms and not worry about the specifics of how we’re going to execute it.”

How important is invention to the work you do with Hoyte, in terms of what you want to accomplish, but would otherwise be unable to with what’s readily available?

I’m always challenging my key crew members to do something we haven’t done before. With Hoyte it’s particularly fun, because he doesn’t just have a cinematographer’s eye; he has an engineer’s brain. Set him a challenge, and he just won’t quit until he’s fully mapped out his vision and how to make it happen. There’s no challenge he shies away from — he’ll go the extra mile to find the solution to a problem when other people would just throw their hands up — and he demands the same from everyone around him.

The unique quality that Hoyte brings to photography is that he’s prepared to talk about an idea in abstract terms and not worry about the specifics of how we’re going to execute it. He can take an emotional, story-based approach to our decision-making process, and he combines that with an intensely practical mind to achieving what we set out to do. Those two things make him one of the great cinematographers of our time.

What’s the most abstract you were able to get with Hoyte on this film?

Instead of thinking about composition in terms of a two-dimensional image, we committed to the three-dimensional idea of camera placement — which we call “following the ball” — which lets me draw the audience into a particular character’s point of view. That’s the kind of thing that sounds like abstract, esoteric theory, but it has a very palpable effect on the audience because we’re really thinking about whose point of view we’re trying to put the audience in. For instance, in the color sequences, the camera is physically closer to Oppenheimer, relentlessly pushing in on his face and his eyes. But in the black-and-white sequences, which are from Lewis Strauss’ point of view, the cameras are physically closer to Strauss, and we’re filming Oppenheimer with longer lenses. It’s these seemingly esoteric disciplines that Hoyte executes in a very elegant way.

We’re not necessarily thinking about a proscenium or balancing the elements within it. It’s a two-dimensional way of thinking better suited to CinemaScope, but we’re shooting for multiple formats, so ours is an aesthetic that was born out of necessity. Over the years we’ve found that the more we think about composition in three-dimensional terms, the better we and the audience engage with the material. It’s like the strategy that James Cameron has taken with 3D, but applied to non-stereoscopic imaging. I refer to it as “3D without the glasses.”

“I’m often accused of being old-fashioned in my methods, or called a Luddite for not embracing digital technology, but so much innovation went into doing things the way we wanted to for this film — the black-and-white 65mm film, the lenses, the lighting — that it would have been unthinkable to make it even five years ago.”

How do you see your relationship with technology developing, given that you prefer to take a legacy attitude to certain aspects of filmmaking, while certain new technologies improve the efficiency of your crew, thereby making ideas like shooting with Imax film cameras more feasible?

Regarding technology, my philosophy is to use the best tools available, in terms of the quality of the image and what will put the audience into the story. For me, that’s photochemical film, particularly 65mm Imax film. In terms of resolution and color, it’s the best analogy for the way the eye sees. On the flipside, Hoyte and his team’s approach to the innovations around wireless LED lighting technology has transformed the way we work.

Can you provide an example of this?

We always knew the Trinity test needed to be a showstopper, so there’s an enormous amount of clever visual and special effects that went into it. But there’s also the most incredible interactive lighting that Hoyte and [gaffer] Adam Chambers and their team put together; that allowed me the freedom to shoot Oppenheimer’s face as he witnessed this incredible event, and then cut into it with absolute precision the interactive lighting and colors on his face, which were synchronized to the explosions. Without that technology, I have no idea how we’d have done it, because you’re seeing a beautiful, subtle, continual interactive lighting change, and you’re seeing it in three different locations, from three different perspectives. That’s very much due to Hoyte’s mastery of the newest technology available.

What can you tell us about working with Kodak to produce the world’s first run of 65mm Double-X stock?

The people who can build things themselves won’t take “no” for an answer because they can just solve these engineering problems themselves. And even when Hoyte’s not doing it himself, he can involve the great minds at Kodak and FotoKem. Going back to The Dark Knight, which was the first Hollywood feature to shoot in Imax, we were told by many people that it wouldn’t work. But with [cinematographer] Wally Pfister [ASC], whom I was working with back then, we persevered and made it happen. I’ve enjoyed having those challenges on every film, and on Oppenheimer, one of the big ones was making large-format black-and-white film. What we were really excited about doing, and what Kodak and FotoKem got excited about doing, was showing that there could still be tremendous innovation in that area, and the results are truly extraordinary.

You know, I’m often accused of being old-fashioned in my methods, or called a Luddite for not embracing digital technology, but so much innovation went into doing things the way we wanted to for this film — the black-and-white 65mm film, the lenses, the lighting — that it would have been unthinkable to make it even five years ago. We had to change the system to make it work for us, and being able to do that has always been important to me.

Here, Panavision Senior Vice President of Optical Engineering and Lens Strategy Dan Sasaki discusses working with van Hoytema to create the special large-format optics used in the film.