Creating a Gentle Giant for I’m a Virgo

Show creator Boots Riley “didn’t want digital doubles; he didn’t want a whole lot of CG. We knew it was possible because they’ve been doing that for 100 years.”

How do you depict a giant 19-year-old man living life in downtown Oakland, Calif.?

That’s the question filmmaker Boots Riley put to visual-effects professionals while preparing I’m a Virgo, his miniseries that follows on the heels of his satire Sorry to Bother You. (Our podcast on the project here.) The Amazon Prime production unfolds from the perspective of 13ʹ-tall Cootie (Jharrel Jerome), who lives a sheltered existence with his Aunt LaFrancine (Carmen Ejogo) and Uncle Martisse (Mike Epps) until he ventures out into the streets and finds love and friendship — and an archenemy.

Expert Perspectives

To investigate the possibilities of forced perspective, the filmmakers consulted with such visual-effects experts as Phil Tippett; Dennis Muren, ASC; John Knoll and Joel Hynek. References included films by Georges Méliès, Darby O’Gill and the Little People, The Gate, Elf (AC Nov. ’03) and The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (AC Dec. ’01).

Adding to the challenge, Riley and cinematographers Steve Annis and Eric Moynier were shooting mostly on location — in New Orleans and Oakland — with stage work housed in an improvised shooting facility in Elmwood, La. “Boots was driving the aesthetic,” says series visual-effects supervisor Todd Perry. “He didn’t want digital doubles; he didn’t want a whole lot of CG. We knew it was possible because they’ve been doing that for 100 years. Boots was the instigator, and then Steve Annis and I wrangled technical aspects.

Anamorphic and Spherical

The filmmakers’ lenses of choice, Series 2 Arri Rental Alfa anamorphics, were swapped out for forced-perspective shots. Annis calculated the fields of view for the anamorphic primes and obtained spherical equivalents: T1.8 Arri Signatures. “When we got into forced-perspective shots, we always switched to the spherical lenses so we could maintain our depth of field,” Perry says. “The camera team came up with solutions to mitigate issues on set. Our focus puller, Zach Blosser, and camera operator, Niels Lindelien, got onboard real fast. They knew exactly what our limitations were. They would tell us, ‘Okay, at this exposure, we’re not going to be able to hit it. Can we get a little bit more light into the scene so we can tighten down our aperture?’”

Scaling Cootie

To assist with scale calculations, Perry enlisted associate VFX supervisor Scott Kirvan, who kept track of Cootie’s 2.1x scale ratio; standard-scale performers stood a proportional distance from the camera, while Jerome occupied foreground — occasionally interacting with half-scale props — on grip-fabricated platforms.

In pre-production, Kirvan, Perry and their team used Unreal Engine to develop techvis. The Unreal playback allowed them to dynamically evaluate the practicalities of accomplishing scale illusions. “Everything was based on the location of the camera,” Perry explains. “We scaled Cootie to the focal plane of the camera. Scott made those measurements and talked with key grip Duane Cooper — the grips had to make the platforms for Jharrel to stand on in the appropriate space.”

When it was impractical to stage scale illusions with performers, the production used scaled puppets created at Amalgamated Dynamics, Inc. (now Studio Gillis). Puppets included 15 3ʹ-tall (half-scale), poseable likenesses of Cootie’s friends and family, and other characters he associated with, and two 13ʹ-tall articulated likenesses of Cootie. The Cootie puppets had photoreal skin texture and body hair, and a fixed, neutral facial expression. Perry also used a dummy Cootie head on a stick to assist camera blocking and performer eyelines. ADI then rod-puppeteered the Cootie puppet’s motions, causing it to shift its weight and move its limbs, and supplied huge mechanical hands for scenes involving Cootie’s finger interactions.

There were two primary techniques for shots in which Cootie made physical contact with standard-sized characters: When Cootie was favored in the shot, the filmmakers framed Jerome handling a half-scale puppet — with the puppets framed obliquely or over the shoulder to obscure the artifice — and if the shot favored a standard-sized character, they captured the real actors interacting with the big Cootie puppet.

Though many scale illusions were achieved in camera, the VFX team — led by VFX supervisors Jamie Barty at FuseFX, Aleksandra Sienkiewicz at Crafty Apes and Yabin Morales at Ollin VFX — added enhancements. “Any time we used the [Cootie] puppet and we needed to see [his] face, we also shot a pass of Jharrel,” Perry explains. “We then composited Jharrel’s head onto the puppet, match-moved his performance and then warped the puppet, retaining Jharrel’s natural movements.”

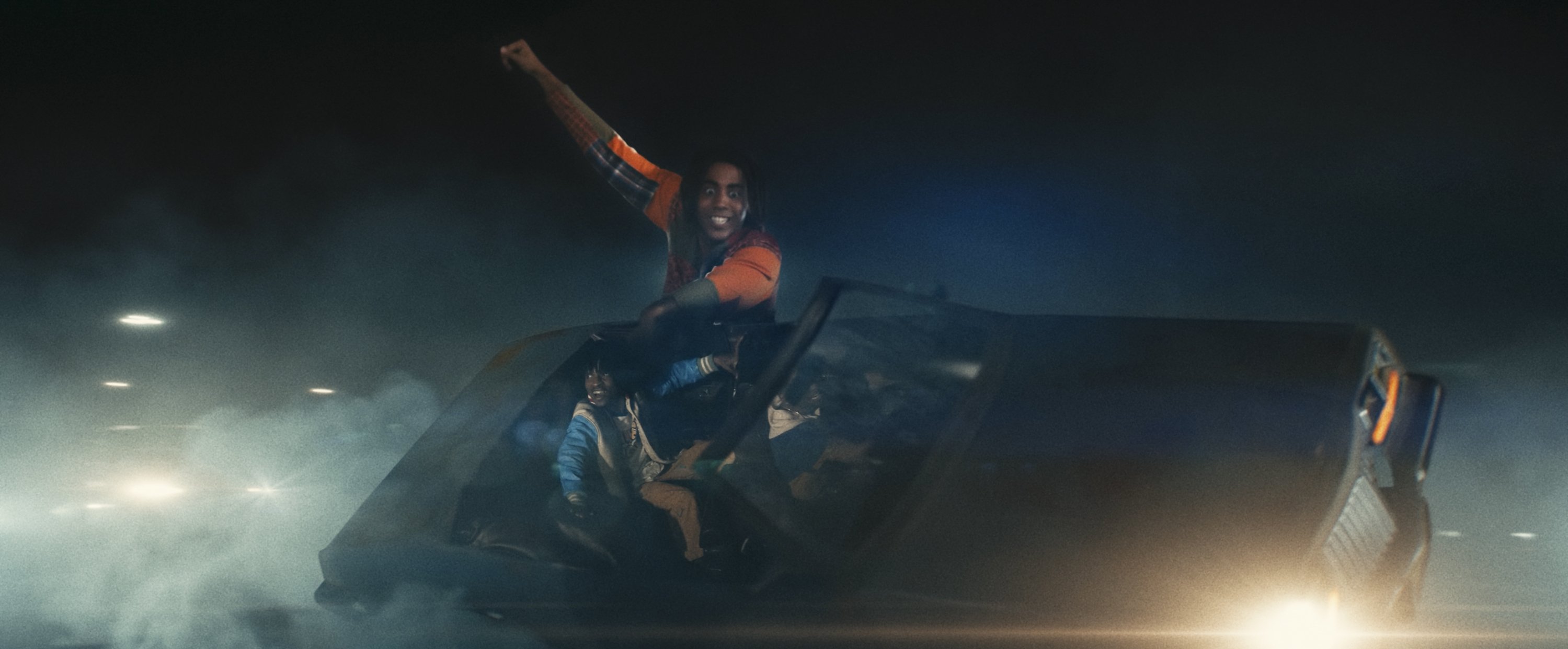

Creating a Joyride

For a scene in which Cootie takes a joyride in a convertible, wide shots were achieved with the giant puppet fastened to a vehicle cruising through Oakland. The VFX team then captured an element of Jerome’s face against greenscreen in appropriate lighting on location. Crafty Apes then digitally warped the puppet’s fingers, simulating Cootie’s grip tightening and relaxing, and tracked in the face element.

Cootie later hangs from the vehicle as his friend does donuts in a parking lot. For that sequence, special-effects supervisor John McLeod built a half-scale version of the convertible connected to a stunt car, which allowed the vehicle to drive canted at 45 degrees on its passenger-side wheels. Riley staged the stunt on location in New Orleans with Jerome wearing a stunt harness that secured the performer to a miniature car, which contained half-scale puppets. The camera team captured Cootie’s spin using a crane mounted to a vehicle that tracked the circular path of the car. In post, FuseFX digitally tracked and modeled the car, projected photoreal flickering-light effects onto the 3D model and sped up the spinning background by a factor of three. “There was nothing forced-perspective about that, but shooting it all in camera gave us the components we needed,” Perry says. “Jharrel’s performance was critical. We made everything work around that.”

Friends and Lovers

Most giant Cootie illusions relied on nimble scale juxtapositions. For a sequence in which Cootie’s friends take him to a nightclub, Jerome performed in the foreground, while the actors portraying the other club guests danced in the background. Cootie’s head occasionally passed behind half-scale, foreground-rigged neon-light strips. Annis shot the club set without atmospheric haze, which was added in post.

When low-key lighting made it impossible to capture depths of field for scale illusions, the team covered scenes with bracketed focal passes, as seen in Episode 3 when Cootie and Flora (Olivia Washington) enjoy dinner at a restaurant. “We shot the performers together, but we shot different takes where our focus was in different planes,” Perry explains. “We shot Cootie’s pass with Jharrel in focus and Flora’s pass with Olivia in focus. Our depth of field was so shallow that when we were focused on Cootie’s face, his knee was out of focus. So, I had the focus puller do a slow rack through the focal planes so we could get an element of his knee in focus.” Ollin assembled the composite, and incorporated GoPro footage of Cootie — captured from an off-camera, reverse-angle perspective — to create a subtle mirror-image reflection of the giant in the restaurant window.

Lighting was key to sequences of Cootie crammed into indoor locations, including a liquor store where he attempts to buy alcohol. The production set up a half-scale shelf of snacks on location in a real liquor store, and grips rigged miniature fluorescent light strips above the forced-perspective platform to cast interactive glows on Jerome.

In Bing Bang Burger, the fast food joint where Cootie meets and later romances Flora, Jerome performed on the platforms with a padded greenscreen horizontal bar above him to delineate his character’s ceiling height. Crafty Apes added digital shadowing and reactive lighting to sell Cootie’s proximity to the ceiling.

For Cootie and Flora’s after-hours love scene — set in a back room at Bing Bang — the production constructed a half-scale set adjacent to the main set. By juxtaposing Washington in the main set with the giant Cootie puppet and Jerome in the smaller set with a half-size Flora puppet, Riley captured spontaneous, interactive performances without the performers ever touching. VFX created illusions of physical contact by rotoscoping, repainting and compositing the lovers’ union. Perry recalls, “When they’re post-coital on the floor, she has her arms around him and he reaches for his phone — with Jharrel moving underneath her. FuseFX tracked what Cootie’s skin was doing, did a subtle grid warp to pull her arm over as his skin was moving, and then transferred that motion to her arm to get the connection to work. When Flora kissed Cootie, Olivia was kissing the big puppet head. That gave us our connection and compression on her lips. Then we replaced the puppet head with Jharrel’s head. We matched where they needed to be and fudged it in the comp.”

Cootie’s World

Dual sets also played a part in Cootie’s oversized apartment, where the production built half and full-scale apartment sets side-by-side on stage. Jerome performed in the half-scale set, while the other performers acted simultaneously in the adjacent full-scale set with giant-sized Cootie puppet pieces. Riley directed with a microphone into the two sets, with cameras placed proportionally at the same angle, mostly locked off.

Fanciful elements of Cootie’s world also featured miniatures that cinematographer Carl Miller photographed at 32Ten Studios in San Rafael, Calif. These included a 1⁄12-scale structure of an Oakland house on stilts that VFX composited into plates captured in New Orleans — and a 1⁄100-scale San Francisco Brutalist skyscraper representing the MCI building, headquarters of Jay Whittle (aka “the Hero,” played by Walton Goggins), which VFX composited into plates captured in San Francisco by 2nd-unit cinematographer Steve Condiotti.

For later episodes, where disenfranchised residents of Oakland’s Lower Bottoms district shrink to Lilliputian size, Condiotti shot background plates for these scenes on location in Oakland. The filmmakers previewed the plates using QTake video assist, then mimicked the lighting on the Lower Bottoms performers in New Orleans. VFX then layered composites, emulating miniature depths of field — which are required due to the nature of miniature photography — by deriving digital depth maps from footage and creating defocus effects.

Psychic Theatre

The narrative takes another stylistic leap for two episodes in which Jones (Kara Young) gives impassioned political speeches and the world around her transitions into “Psychic Theatre.” For the first instance, stop-motion figures and buildings were animated at Mystery Meat Media and comped with digital glimmer effects into a musical stage proscenium. The latter involved stage work that transitioned from surreal vignettes enacted by “graysuit” dancers; FuseFX digitally replicated the graysuits to create a pile of bodies that stack around the Hero.

The Human Touch

The eclectic array of visual-effects techniques were all designed to maintain an emotional connection. “Boots likes to see the ‘seams,’” says Perry. “We shied away from fixing shots that weren’t perfect. The idea that Cootie moves like a puppet was intentional. We tried to make it feel like Cootie was physically there without refining him or adding animation. Boots wanted to feel that substantive connection. Even if an effect might not feel technically real, it can be involving because there’s so much character to it — you believe it’s happening. That’s what Boots was trying to tap into.”