Divide and Conquer: VFX for Napoleon

Visual effects supervisor Charley Henley leads multi-front effort to bring director Ridley Scott’s densely layered vision to the screen.

Editor’s note: As these images were supplied by the participating visual effects companies, they may differ in color and contrast from how the completed shots appear in the release of the film, as they did not pass through the final timing process.

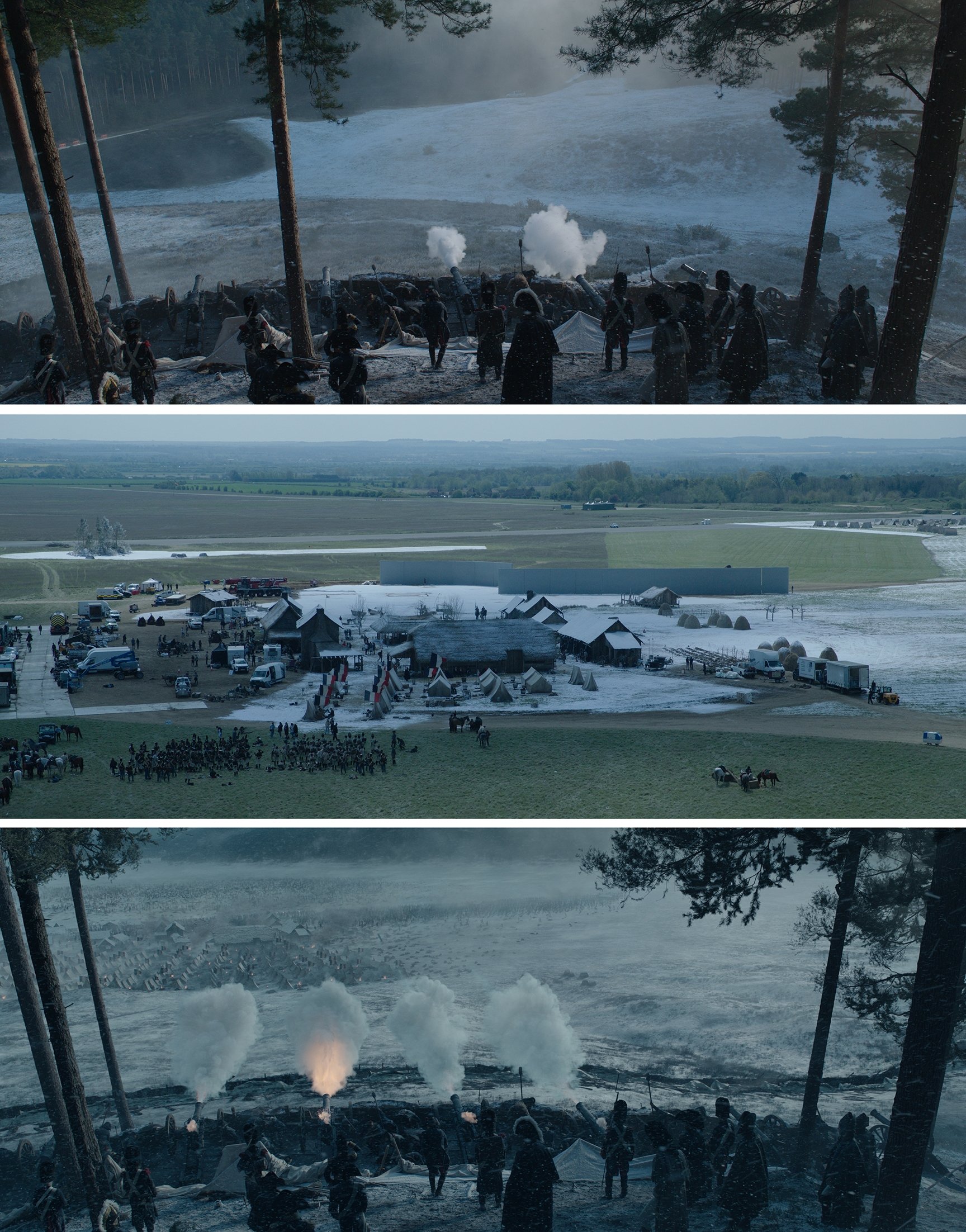

To recreate the Napoleonic era (1799-1815) for the Apple+ production Napoleon, director Ridley Scott, Dariusz Wolski, ASC and production designer Arthur Max teamed with an army of visual-effects, special-effects, and miniature-effects teams to artfully augment what they could accomplish in-camera.

Leading the Napoleon VFX initiative was the production’s VFX supervisor, Charley Henley, marking his sixth assignment for Scott — including his work as a digital artist on Gladiator (AC, May 2000). Joined by VFX producer Sarah Tulloch, Henley marshaled visual effects from preproduction through to final outputs, drawing on the resources of 15 studios based in the U.K., U.S. and Europe, together with an in-house VFX team at the Napoleon production base in London.

Preproduction, 2022

Henley’s role included early collaborations to brainstorm the conceptual approach toward the recreation of historical environments and, in particular, six battles across Europe and North Africa that interwove the tempestuous love story between the despotic French emperor Napoleon (Joaquin Phoenix) and his lover Josephine (Vanessa Kirby). “As you get into films that have a more weighty aspect of the VFX, it generally pays to bring in VFX early and have them work alongside the other heads of department,” notes Henley. “The VFX supervisor becomes one of the longer-running roles on a show, starting in preproduction. Visual effects are often quite a large part of the budget and producers want to figure out early what they’ll need. That involves establishing our relationship with the production designer and the cinematographer. We get in early, knowing that on a larger film, we’ll potentially bring in more visual effects supervisors to divide and conquer.”

The VFX team included Moving Picture Company, which focused on the climactic Battle of Waterloo, the French army’s march into Moscow, and scenes around Napoleon and Josephine’s palatial homes in France. Meanwhile, Industrial Light & Magic handled a snow battle at Austerlitz; BlueBolt Visual Effects focused on the siege of Toulon and Paris riots; Outpost VFX handled Napoleon’s exploits in Egypt; Light VFX attended Napoleon’s Battle of Borodino in the Russian tundra; One of Us assisted opening scenes of Marie Antoinette’s beheading; and Freefolk, PFX, Ghost VFX, Cheap Shot and The Magic Camera Company rounded out the team. Argon Effects and The Third Floor provided previsualization, Visualskies the scanning of sets and props, and The Imaginarium Studios handled motion capture.

One of Ridley Scott’s long-time collaborators, special-effects supervisor Neil Corbould, provided mechanical rigs and pyrotechnics, while prosthetic effects designer Cliff Wallace and his team added to the viscera. On-set VFX supervisor Richard Bain accompanied the shoot on locations in the U.K. and Malta, allowing Henley and Tulloch to plan VFX strategies and key issues, while the in-house VFX team worked alongside the production at Twickenham Studios.

“The idea from the beginning,” states Henley, “was to put in front of camera as much real as possible until that became impractical. So, instead of building 48 tall ships, we got one — and that was a good start. The impracticality of finding 40,000 troops and getting them all ready [for camera] in the morning meant Ridley wouldn’t be shooting at nine in the morning and we wouldn’t make our day. So, we had to find a balance [with VFX] in getting such a huge film done in an efficient time. We always started with real elements, and Ridley laid down what he wanted on the shoot.”

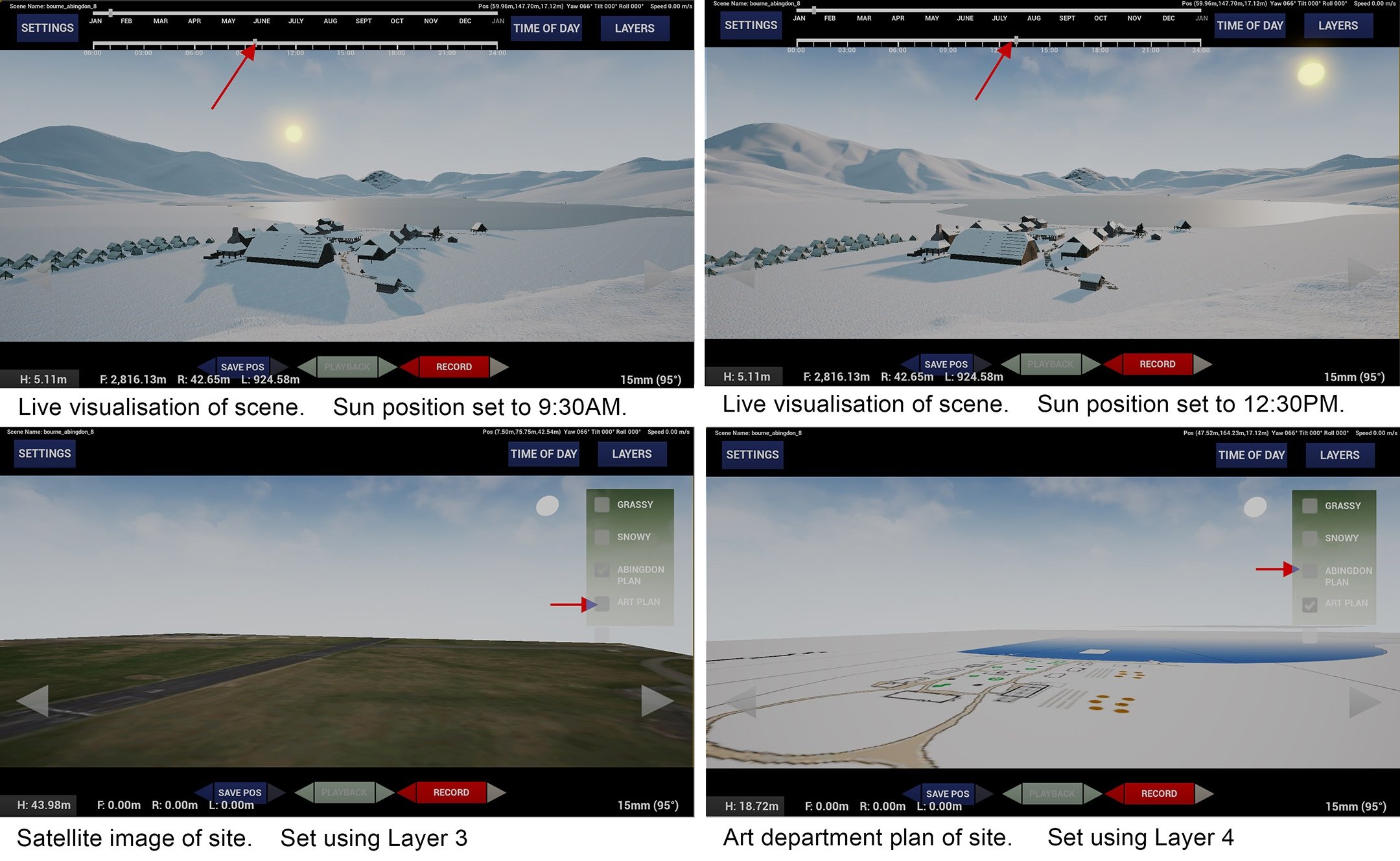

To keep up with Scott’s rapid-fire production pace — using multiple cameras in natural terrains and English stately homes — in-house digital artist Daniel Rickard developed a real-time previsualization tool, called V-Pad, that simulated blends of visual effects with production photography. “Dan did a lot of visualization and he built all our apps,” explains Henley. “In prep, we often involve previz companies to work out the logistics of what we were going to do technically and to explore potentially problematic scenes. For example, we prevized Austerlitz with Argon.”

“I think of Ridley as an artist. Visual effects are one of his brushes. It’s part of the layering of his images. It’s his final layer.”

— VFX supervisor Charley Henley

The snow battle involved a combination of two locations, a forest overlooking an enemy village on a frozen battle plain, which VFX helped align on set. Henley adds, “Dan’s app allowed us to line up shots, apply the camera lens, and we could view any part of the set looking back at the other set. The camera operator could then see they might need to tilt down to frame the village from the woods. Or, in the village looking back to Napoleon in the woods, we could check the framing and the lens were going to work for VFX.”

Toulon, 1793

This previs tool also assisted scenes of Napoleon’s assault on the Royalist and British-occupied port of Toulon. The production selected Fort Ricasoli in Malta as the location for the dockside stronghold. Arthur Max augmented Ricasoli’s architecture with a rooftop set built in the fort’s courtyard. BlueBolt stitched the rooftop set to the surrounding area. “We were inside the fort, so from the outside you’d look back and see the real fort,” notes Henley. “A lot of work around that set was to do with establishing a look for the night skies. The sequence has so many explosions, with lighting coming from the fire, so a day-for-night effect never would have had that drama. Neil Corbould’s team created practical explosions. If an explosion occurred near camera, or if we needed more fire light, we also used LEDs that could flash to create interactive light. For bigger burning areas, Dariusz set up powerful lights to represent fire. VFX later replaced those lights with fire.”

To establish a forest of tall-ship masts docked at Toulon, the production moored the three-mast frigate Étoile du Roy – redressed as HMS Inconstant – in Valletta Harbor. BlueBolt generated an additional flotilla in 24-gun, 34-gun, and 104-gun, three-deck Victory-class configurations.

“Our biggest ship was modeled on the real HMS Victory,” says Henley, referring to the 245-year-old Royal Navy vessel that now serves as a museum ship. “We also shot aboard the Victory in Portsmouth [England] for later scenes when Napoleon has been caught by the English. The Victory was part of the British fleet in Toulon, so that was a nice historical link. Looking down from the fort where the ships are all lined up and they're bombarded by mortars of molten lead, one of those ships was real and the row boats and stunt guys were real. We took the real ship out to sea to shoot plates as a basis for all the other ships in the British Navy fleet.”

To add to the conflagration of tall-ships receiving molten mortar fire, Magic Camera Company built 1/4-scale masts, sails, and rigging to represent various classes of tall-ships that they filmed igniting and collapsing during a nocturnal airfield shoot.

Napoleon distinguishes himself in battle at Toulon after his horse is horrifically shot out from beneath him. Scott captured the horse fall on location in Malta using a mechanical-effects rig that Corbould’s team created to fling a stunt double from its back. “The motion rig was repeatable and had a moveable dummy horse’s head and back but no legs,” Henley explained. “We had that rig off to the side of the set, and we shot it on one of the nights during the main battle. That way we knew exactly where Joaquin and the real horse were, and the lighting. We shot quite a few takes until we nailed the action. We then lined up a special-effects exploding chest piece for the horse in the same lighting. MPC generated the digital horse to add legs. The tricky part was the horse’s fall, but we managed to find a reference clip of a poor horse that collapsed on its back legs. And then we added a cannonball impact as a blend of real and animated gore. It was a crazy moment, but it gets Napoleon covered in blood for the battle.”

Egypt, 1798

For Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt, Jean-Léon Gérôme’s 1886 painting Bonaparte Before the Sphinx served as inspiration for a dramatization of the French emperor contemplating the Great Sphinx of Giza before attacking Mameluke soldiers.

The production staged the scene on a polo field in Malta, where VFX erected desert-motif “sandscreens” to back a plateau of sand and rubble as Joaquin Phoenix sat atop his horse. Digital effects artist Dan Rickard captured plate shoots of sand dunes in Morocco, which Outpost VFX later assembled in a recreation of the scene.

“The Sphinx looks different now from how it did historically,” notes Henley. “It has been excavated so more of the Sphinx is visible. Dan found locations in Morocco for dunes and big plateaus with a ridge that appears in the background where the French army is in the background as Napoleon rides up. We shot a few horses and camels in Malta for reference. Outpost then added more camels and the digital army marching across the desert. They built a digital pyramid and Sphinx head, referencing the real site blended with the painting as a look.” A line of costumed cavalry served as Mamelukes, whom Napoleon scares away by ordering cannons to fire on the pyramids. “The Mamelukes were more traditional 2D duplication. We shot multiple plates of them reacting, and Outpost composited them to get the numbers working.”

Paris, 1804

Among the locations used to depict Revolutionary-era Paris, thirteenth-century Lincoln Cathedral, located east of Sheffield, served as the interior of Notre-Dame Cathedral. The English Gothic architecture was a close facsimile to Scott’s visual reference of the 1807 Jacques-Louis David painting The Coronation of Napoleon. Outpost VFX provided digital crowd replication and PFX added digital candle flames.

Candlelight was a focus of preproduction experimentation with Dariusz Wolski when it became apparent that safety parameters forbade the use of naked flames in ancestral locations. “Dariusz came to us early to team up on this one,” recalls Henley. “His guys wired hundreds of candles with little LED bulbs. The shape of the bulb was just smaller than a candle flame. We camera tested them side by side with real candles to match the color value and flicker.”

A key scene, where Napoleon first meets Josephine across a candlelit salon — filmed at Petworth House in West Sussex — featured a plethora of glowing candles and fireplaces that Wolski also replicated with LED panels. “Once we had that lighting in the scene, sometimes if the candles were out of focus, they worked. But PFX did digital replacements of 1,200 candles. That involved a lot of camera tracking and rotoscoping. After that, it came down to meticulously laying out the candle flames by hand. Ridley sometimes wanted flickers, so if a character walked by, the candle flame would flicker. PFX made that happen.”

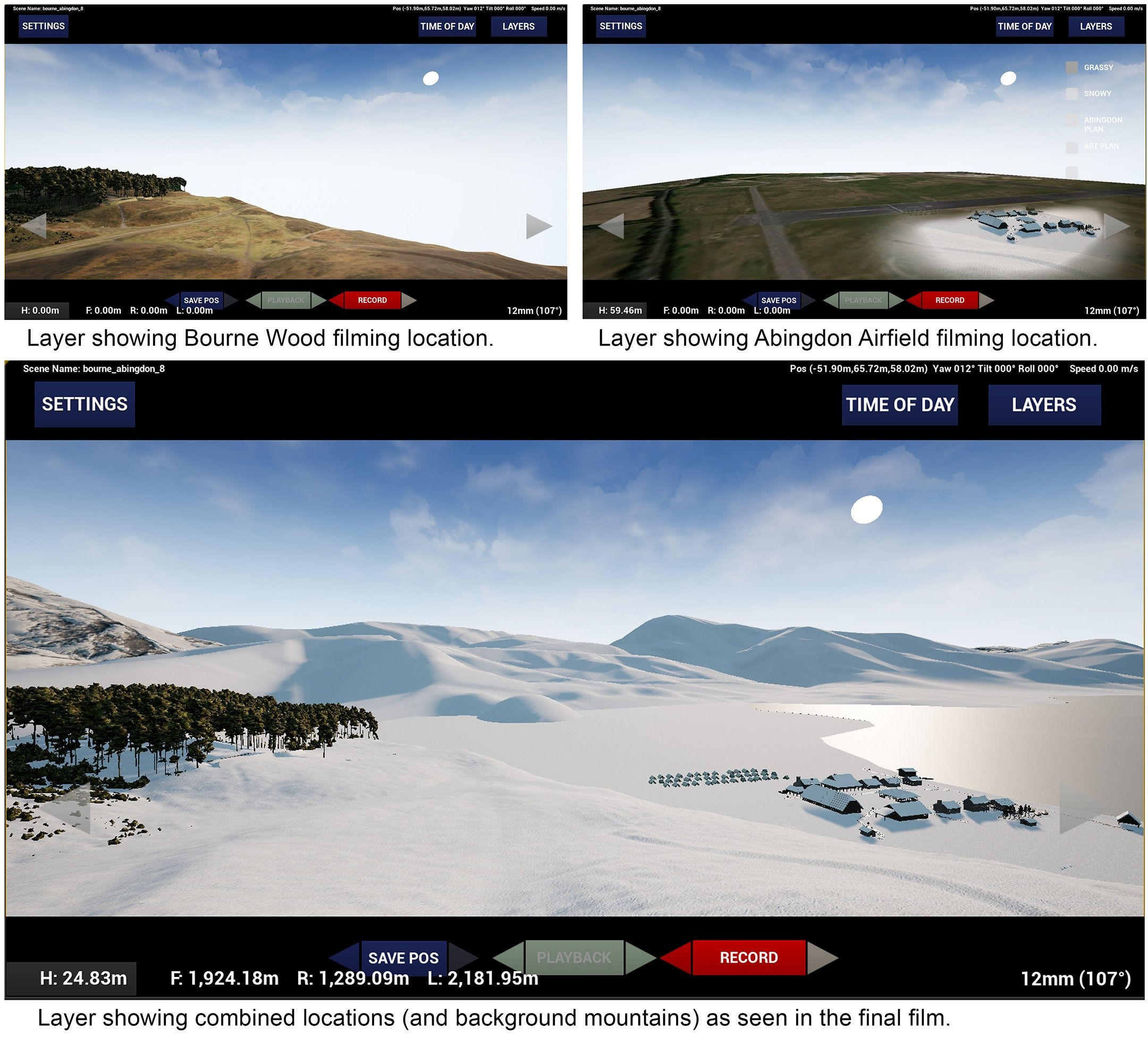

Another English manor house served as a basis for the façade of Château de Malmaison, Josephine’s later domicile after she is separated from Napoleon. Outpost VFX digitally replaced the manor house’s roof and windows to more faithfully represent French architecture of the period. For Napoleon’s Tuileries Palace, destroyed by arson during the riots of the Paris Commune, the production made use of Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire. MPC augmented Blenheim’s façade with 3D modeling and digital matte painting to mimic window shapes and limestone masonry similar to the French Baroque architecture of the present-day Louvre Museum.

Austerlitz, 1805

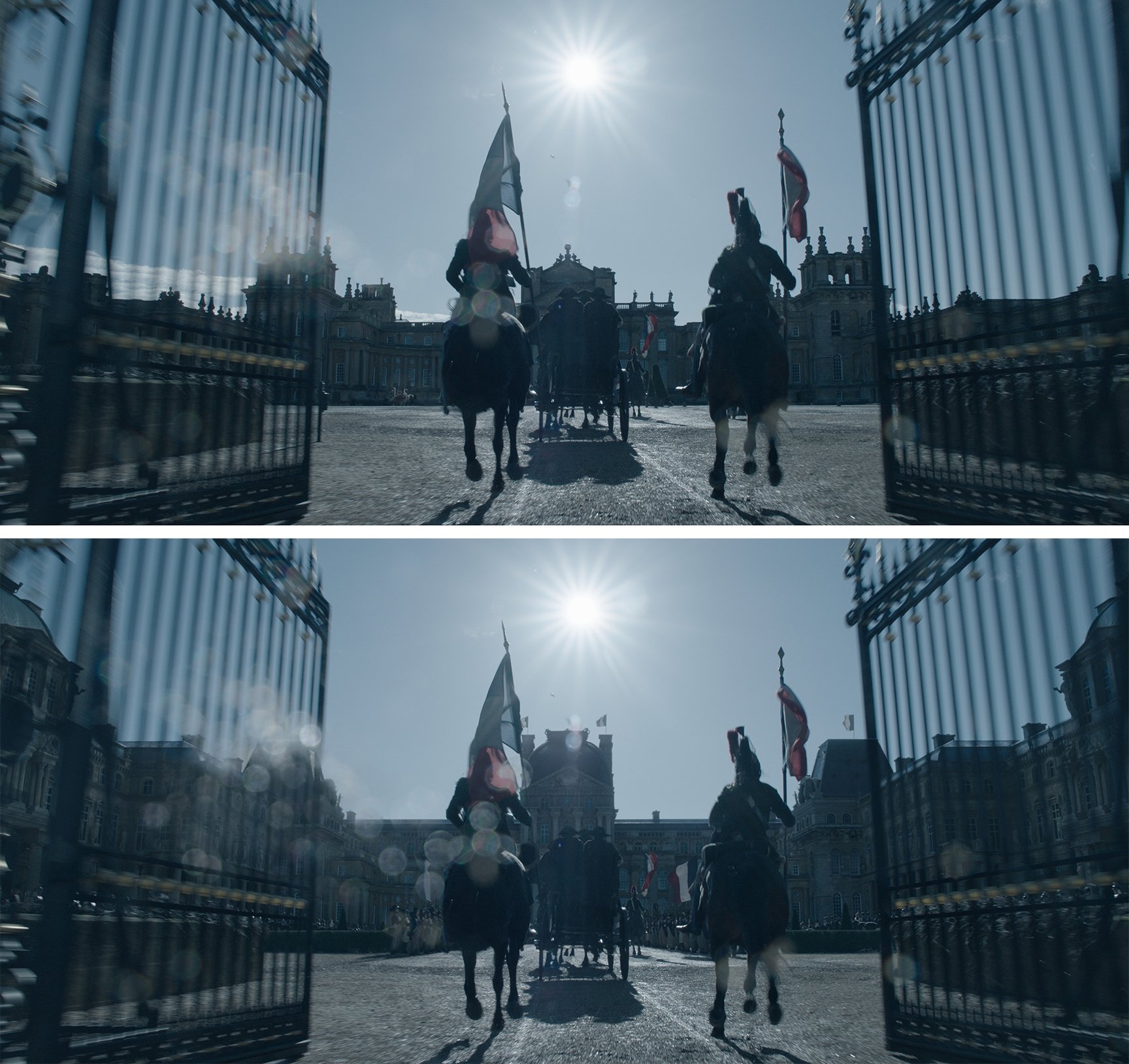

To stage Napoleon’s clash with Russian and Austrian troops at Austerlitz, the production selected locations in Bourne Wood in Surrey and RAF Abingdon in Oxfordshire. “Finding the Austerlitz location was a challenge,” says Henley. “For a while, we were looking for areas with woodland and a slope where Neil Corbould could build a big flat area. We looked for a place to shoot an area with real snow, or on a real frozen lake. We ended up shooting it in components, which made this quite a visual effects challenge.”

Dan Rickard’s on-set previsualization tool enabled the alignment of compositions, with higher elevations of Napoleon’s forces in Bourne Wood, and reverse angles from the Russian encampment built on Abingdon’s airfield. ILM combined locations into stunning snowbound vistas wreathed in freezing fog.

Wide shots revealing the Austrian Army advancing from a veil of mist featured digital matte paintings that ILM generated from photographic textures and synthetic fog effects. “Ridley wanted the fog to be like a character in the battle,” notes Henley. “It’s an element that creates surprise and is part of [Napoleon’s] trickery. We had fog [effects] on set. We shot takes with and without. That locked us into a look. Then, our VFX unit shot background plates and elements in southern Italy, at Campotosto in Abruzzo, and the Italian Alps. That guided the look for how the trees met the snow. ILM used those components and plates from both setups, they created a digital version of the environment, and brought all that together.”

For the climax of the battle, when French artillery shatters the lake ice beneath the Russian Army’s feet, Neil Corbould’s team dug water tanks into Abingdon Airfield, a former RAF base. “They had one large tank and several smaller tanks with a layer of fake ice built on top that stunt performers could run across,” Henley observes. “They could trigger a release and soldiers would drop in. There was a big system of air mortars to make water spray up without hurting anybody. They even had a ramp so that horses could get into that tank and be in the water, all shot on location.”

Shots of soldiers and horses struggling underwater were accomplished during a water-tank shoot at Pinewood Studios. Corbould’s special-effects team simulated ice using layers of wax, and rigged prop cannonballs suspended on lines running into the water. Pulled through the water at speed, the cannonballs created natural air-bubble trails. ILM then digitally enhanced the scene, including a nightmarish shot of a Russian standard bearer and a horse sinking into the icy depths. “Neil put a dummy horse in the water,” notes Henley. “We pulled the camera up, to enhance the sinking effect, because of limited depth in the tank. We could never get the motion on the flag to tell the story of the soldier and the horse, so the flag is digital. And ILM added digital horses swimming in the water.”

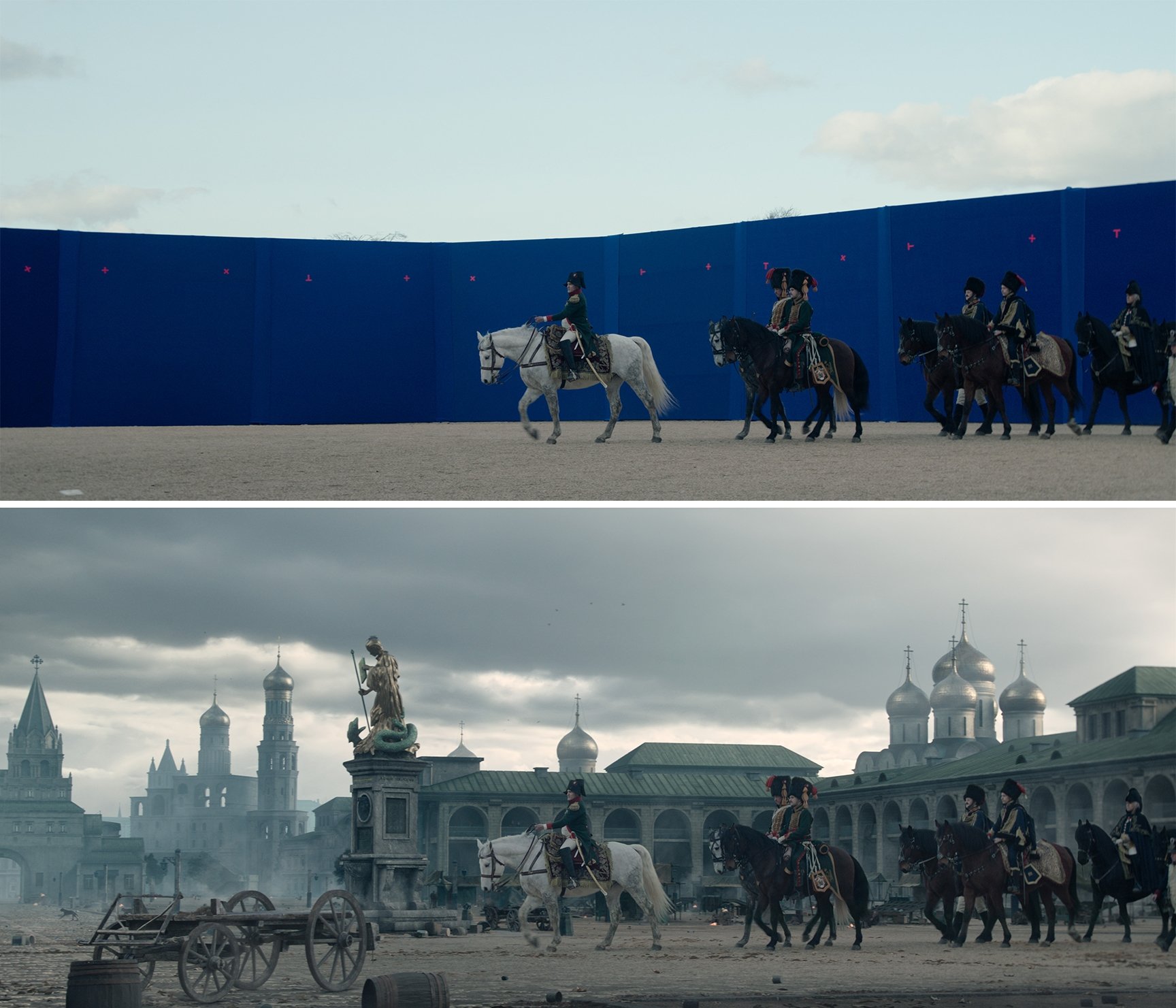

Moscow, 1812

Napoleon’s fortunes turn sour on his campaign into Russia, which culminates in a surreal sequence when the French Army discovers Moscow first deserted and then in flames. The production shot the march into Moscow at Blenheim Palace, located outside Oxford. “The courtyard spaces there worked well for Moscow and the approach to the city when they're walking through the trees,” observes Henley. “Arthur Max provided ground-level dressing, blocking out windows so the city felt boarded-up. MPC added Moscow in the background with its amalgamation of architecture, and we added everything above the first floor.” Architect Inigo Minns from The Architectural Association in London advised on architectural styles, which assisted MPC’s set extensions that blended Russian styles with Blenheim Palace.

For burning Moscow, as Russian rebels torch the city at nightfall, Wolski placed lights in the shot to simulate source points of illumination and MPC integrated in-camera blooming effects in digital composites. “If characters’ heads crossed lights and caused them to burn out,” Henley explains, “we made use of those effects. We also shot elements of embers. Neil Corbould’s team set fire to a barn with a thatched roof, which created massive flames. We used those elements to create a sense of scale. And then, we combined that with simulations of buildings collapsing.”

Waterloo, 1815

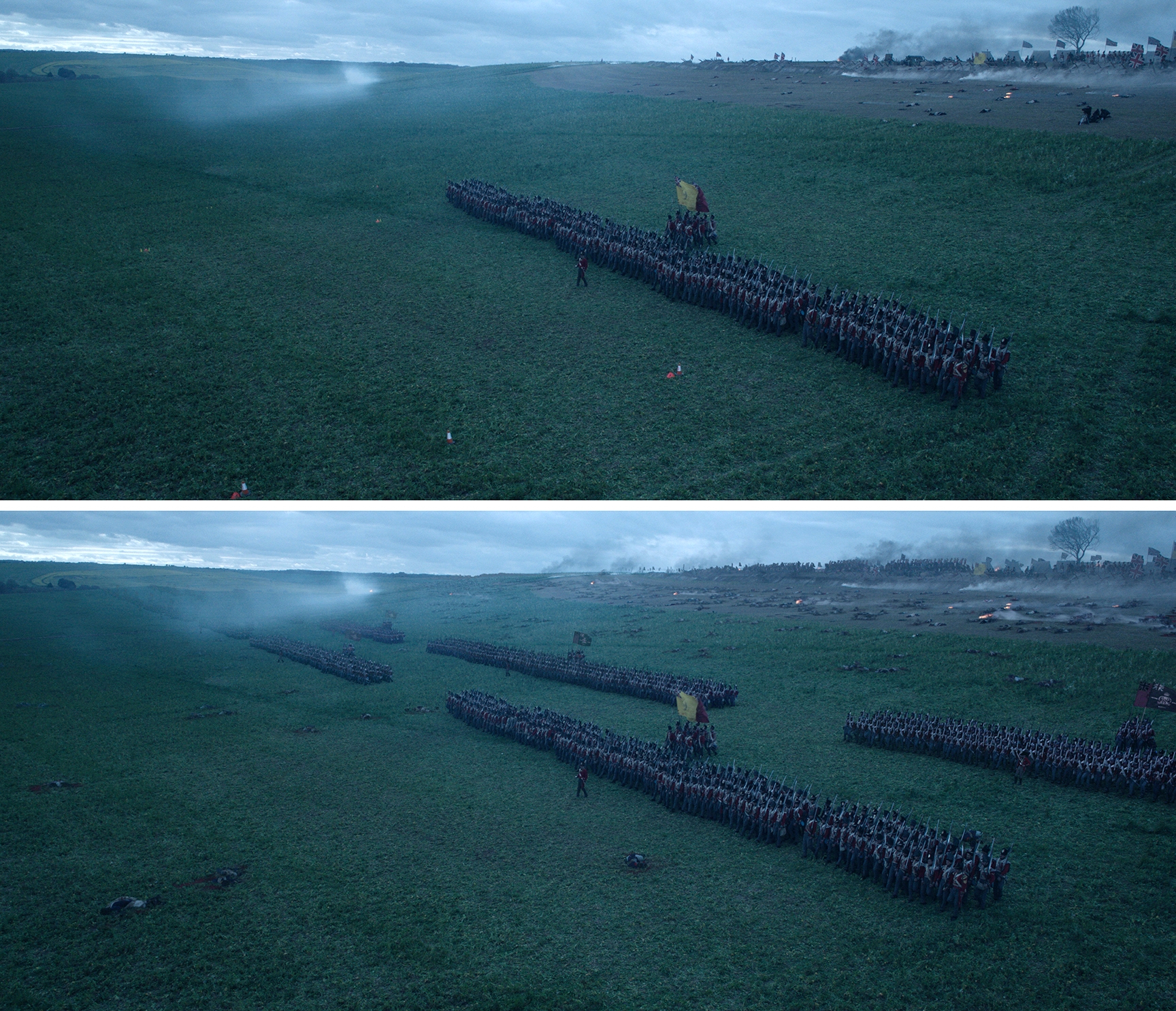

For Napoleon’s final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, the production selected a sloping meadow at Churn Farm in Oxfordshire. The location offered elevations that approximated historic battle site topography and afforded Scott and Wolski mile-wide perspectives of French and British Coalition forces. Corbould’s special-effects team supplied rain rigs fed by water tankers to simulate inclement weather, but Mother Nature assisted. “On the first day, we shot there from the French side,” Henley recalls, “it was raining, it was sunny, it was incredibly windy, and then it hailed — we had every type of weather. The skies were incredible. It was such a gift. After that, it was tough to keep consistency across the scene. But what we had in those first few days gave us all that Ridley wanted. It was so windy, the special-effects rain was blown sideways and the flags were blowing like the clappers. The drama of that was fantastic. And so, when the wind stopped, we knew we’d have to put flags blowing in all our shots.”

Historical advisors guided battle action on location. VFX captured elements from additional perspectives for MPC’s later use in the digital replication of armies. “While the battle was going on,” relates Henley, “VFX did everything we could to help make the shots look great in post. Whenever shots didn’t require the full range of dressed stunt doubles, we pulled soldiers to the side and shot plates for scenes that we’d captured earlier in the day. In certain cases, we set up an additional camera offset further back [from the main unit camera]. That allowed us to double up lines of soldiers. In several shots that worked nicely as a compositing job because we had them for real. In other shots, we knew we’d have to match the crowd digitally.”

In wide shots, MPC generated an estimated 70,000 soldiers and 5,000 horses, with 60 varieties of uniforms, equipped with armor, muskets and artillery effects. To capture battle choreography for animated assets, The Imaginarium Studio staged motion-capture sessions with costumed performers in a paddock at The Devil's Horsemen animal training facility in Salden, Buckinghamshire. “Each of the armies had their own way of moving,” notes Henley. “They had different ways of marching, running, loading, and firing guns. And they also maneuvered in different formations. A tricky one in Waterloo was how the infantry moved into defensive squares. They were all pushed up against each other, which changed the soldiers’ body language as they moved around. One side of the formation was three [rows deep] by 20 people [long], so it contained 100 soldiers moving around, some pressing forward, some backward, some remaining in place — it was a complex series of actions. On top of that, we did a lot of motion capturing of maneuvers with the horses.”

Waterloo vistas included environment extensions, digital removal of tracking vehicles and camera operators, and sky replacements, including aerial perspectives of clouds occluding the battlefield. “Ridley loved cloud shadows moving across the landscape,” adds Henley. “One of his first drawings [in planning the scene] was of a big aerial shot with patches of cloud. Using our reference plates, we had the ability in post to take sunny shots and add patches of clouds, or take cloudy shots and insert a sun patch. By orchestrating those effects, we could guide where we wanted the audience to look.”

Visual effects complimented the grand scale of the production with close attention to detail, unifying visual elements.

“I think of Ridley as an artist,” concludes Henley. “Visual effects are one of his brushes. It’s part of the layering of his images. It’s his final layer. Ridley is incredibly pragmatic about what he wants to shoot and when it makes sense to use visual effects. Alongside that, he has this beautiful eye. When Ridley creates a drawing, everybody becomes enthusiastic to match that, and then he’ll take it further. I think his consistency of vision is what helps bring all the different departments together.”

You'll find our complete production story on the film here and our interview with Ridley Scott here.

Additional insight can be gleaned from these reels by MPC, ILM and BlueBolt: