The Creator: Fiction From Fact

“He wanted to go to real locations with a small footprint and create visual effects afterward.”

Director Gareth Edwards had an unusual brief for the visual-effects team on The Creator: Their work would have to mesh with a freewheeling, pseudo-documentary shooting style.

Set in 2070, the sci-fi story follows Army veteran Joshua Taylor (John David Washington) into robot-populated New Asia to hunt an AI super-weapon that turns out to be a childlike “simulant” named Alphie (Madeleine Yuna Voyles). “Gareth told us he wanted to take the best of his experience on [his 2010 theatrical-feature debut] Monsters and pair it with the best of his experience on Rogue One [shot by Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS; see AC Feb. ’17],” recalls Jay Cooper, the film’s visual-effects supervisor. “He wanted to go to real locations with a small footprint and create visual effects afterward. Instead of the formal studio approach — doing large production builds — he wanted to dovetail those processes with storytelling.”

Proof of Concept

To translate the theory into practice, Industrial Light & Magic contributed to a proof-of-concept reel. “This was about a year and a half before Covid-19 — before we had a production designer or final designs,” says Cooper. “Gareth traveled to Nepal, Thailand and Vietnam and used a prosumer camera [Nikon Z6] to shoot a Baraka-like, meditative piece. [ILM executive creative director] John Knoll, [conceptual artist] James Clyne and several other ILM folks then created 40 shots, which Gareth used to help get the movie greenlit. It was the germ of how he wanted to shoot … [and] some of those shots survived [in the final]. There’s one of a robot on a moped that Gareth shot three and a half years ago!”

A Case-by-Case Basis

Clyne stayed on as the film’s production designer, collaborating with ILM through post-production. “We constructed shots a little differently from the way I’ve done it in the past,” Cooper says. “We’d get a shot up on its feet, and James would do a paint-over to tweak forms. Then we’d do another version and go back and forth with Gareth. We created this world on a case-by-case basis. There were a lot of one-offs.”

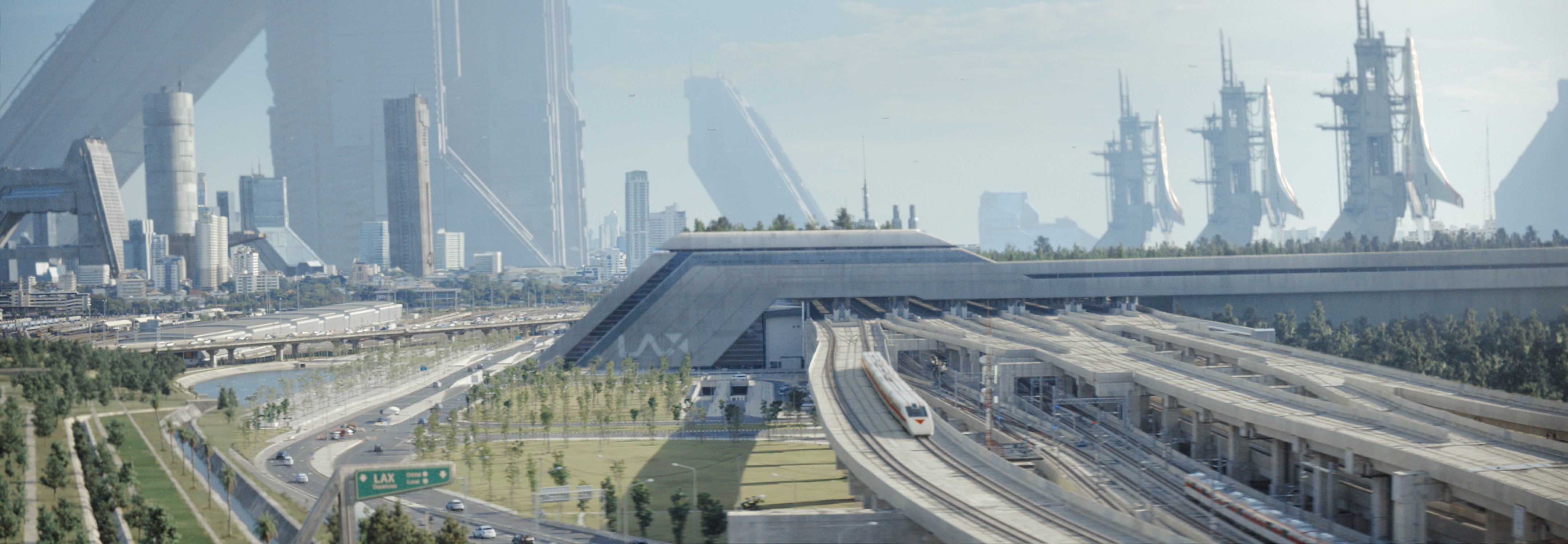

The “one-offs” Cooper mentions refer to a significant number of big CG builds that are seen briefly, and then not seen again — including environments in post-apocalyptic Los Angeles and gigantic AI structures in New Asia. Co-cinematographer Oren Soffer spent four months shooting the film on locations in Indonesia, Cambodia, Nepal, Tokyo and L.A., with Edwards as the primary camera operator — and a team led by special-effects supervisor Neil Corbould supplying interactive pyrotechnic and atmospheric effects, for the VFX to be incorporated later. ILM visual-effects supervisor Andrew Roberts accompanied them, gathering reference material that included drone footage for environment work that, in some cases, would ultimately feature fully synthetic digital builds for large-scale destruction. On set as well were crewmembers from Wētā Workshop, which supplied futuristic hardware and prosthetics, including cybernetic appendages for Joshua’s missing arm and leg.

Low-Orbit Volume

Having developed renowned expertise with ILM’s StageCraft from his work on The Mandalorian (AC Feb. ’20) and The Batman (AC June ’22), Creator co-cinematographer Greig Fraser helped to conceptualize two LED-volume sequences set on a 15,000'-wide low-orbit platform called the North American Orbital Mobile Aerospace Defense, aka NOMAD. The craft’s airlock and biodome featured expansive high-tech environments, which were realized with the help of interactive LED-wall backgrounds at Pinewood Studios in England, which ILM visual-effects supervisor Frazer Churchill and his team prepared at the studio.

Global Effects

ILM visual-effects supervisors Ian Comley, Charmaine Chan and David Dalley worked with Cooper at ILM’s studios in London, San Francisco and Sydney. As the project grew, New Regency visual-effects producer Julian Levi distributed visual-effects assignments to ILM and more than a dozen additional studios on three continents.

Cooper notes that “it was a non-traditional structure. I had my eye over everything. Ian and Charmaine supervised around 500 shots in London. We had about 250 shots in San Francisco, and 180 to 200 in Sydney. We all worked with Gareth directly. Part of Gareth’s charm is that he likes to be connected to the visual effects, as close to the artists as possible. He was on all of our Zoom calls, and he welcomed artists to join the conversations.”

Designing a Key Character

A special focus was the AI simulant Alphie, who — like her fellow simulants — has mysterious mechanisms at the back of her skull and a chromium tube bisecting her mastoid region that spins as she processes thoughts or emotions. “We had many references for Alphie’s ‘headgear,’” says Cooper. “Mike Midlock, our animation supervisor in San Francisco, found great images of 1970s reel-to-reel computers. This movie has an aesthetic that feels frozen around the time of the Walkman, so we looked at product designs that had that look.”

To help integrate Alphie’s headgear, the makeup department applied tiny facial-tracking markers to Voyles — but no other prosthetics, whose application would take away from shooting time. “Gareth wanted to capture every sunrise and work with his actors as long as possible, especially young Madeleine, who had a limited window, per [child-labor laws],” notes Cooper. “The most complicated component was getting her headgear to feel integrated when Alphie is talking.”

ILM modeling supervisor Bruce Holcomb developed Alphie’s robotics to emphasize the character’s vulnerability by exploring negative space. “We didn’t want the headgear to feel like a physical appliqué,” Cooper explains. “Gareth wanted to be able to see through her neck and earholes, and he wanted that to be impactful. It was a delicate line. If we took away too much, it overshadowed her performance, and if we didn’t do enough, [the effect was lost]. However, we didn’t want the effect to be the only thing you’re looking at. Madeleine was such a gifted actress, and she did an amazing job of emotionally conveying the idea of Alphie’s humanity as a robot.”

Alphie VFX work began with a rigid head track to “lock” robot parts to the performer’s skull. ILM then created digital reprojections of skin textures. “Think about the way skin moves around the edges of your ear when you’re talking — we locked off some of that motion or dialed it out,” Cooper explains. “We used the face as a starting point and then took animation from elements of her face so the skin stuck to rigid connections. We tied motions of the headgear neck and some internal pieces to her jowl movements. And we animated mechanical components attached to her tongue, cheeks and jawline. It was all part of the goal to make it feel integrated — so when Alphie was talking, it felt like parts of her mechanical structure were moving.”

Innovating Through Post

Within the film’s narrative, New Asian society also features a lower stratum of robots, many of which were imagined and added in post as Edwards shaped the story with the editors. “We had a [locked picture] cut about three months after principal photography,” Cooper recalls. “There was so much design work to be done, the cut was almost secondary. We had to design all the robots, simulants, NOMAD, environments, giant tanks, flying ships and vehicles, regardless of the cut, and we were advancing that all along the way.”

ILM eschewed any kind of motion capture on set, electing instead to place background characters in environmentally appropriate attire. Modelers then developed a kit of eight robot heads with a variety of paint jobs that Edwards could select.

“My goal is to maximize production value,” Cooper says. “We made choices as late as possible, in ways that were the most impactful for the story. For example, we had a scene with [humans and] robots running on a bridge. All of those people were cast as extras and wore character-appropriate costumes. Gareth pointed to one person running who did a head turn, and he asked us to make that [character] a robot. That [spontaneity] is what made those moments work — we made those choices for the benefit of the viewer.

“It’s funny,” Cooper adds. “Gareth says he hasn’t kept up with the software, but he’s so clued-in. Even if he doesn’t know the details, he understands the process. He speaks the language. And he knows where to ‘cheat’ — where some techniques are expensive, and where others are not. That was hugely helpful.”

You’ll find our complete production report on The Creator here.