Dark Waters: Truth to Light

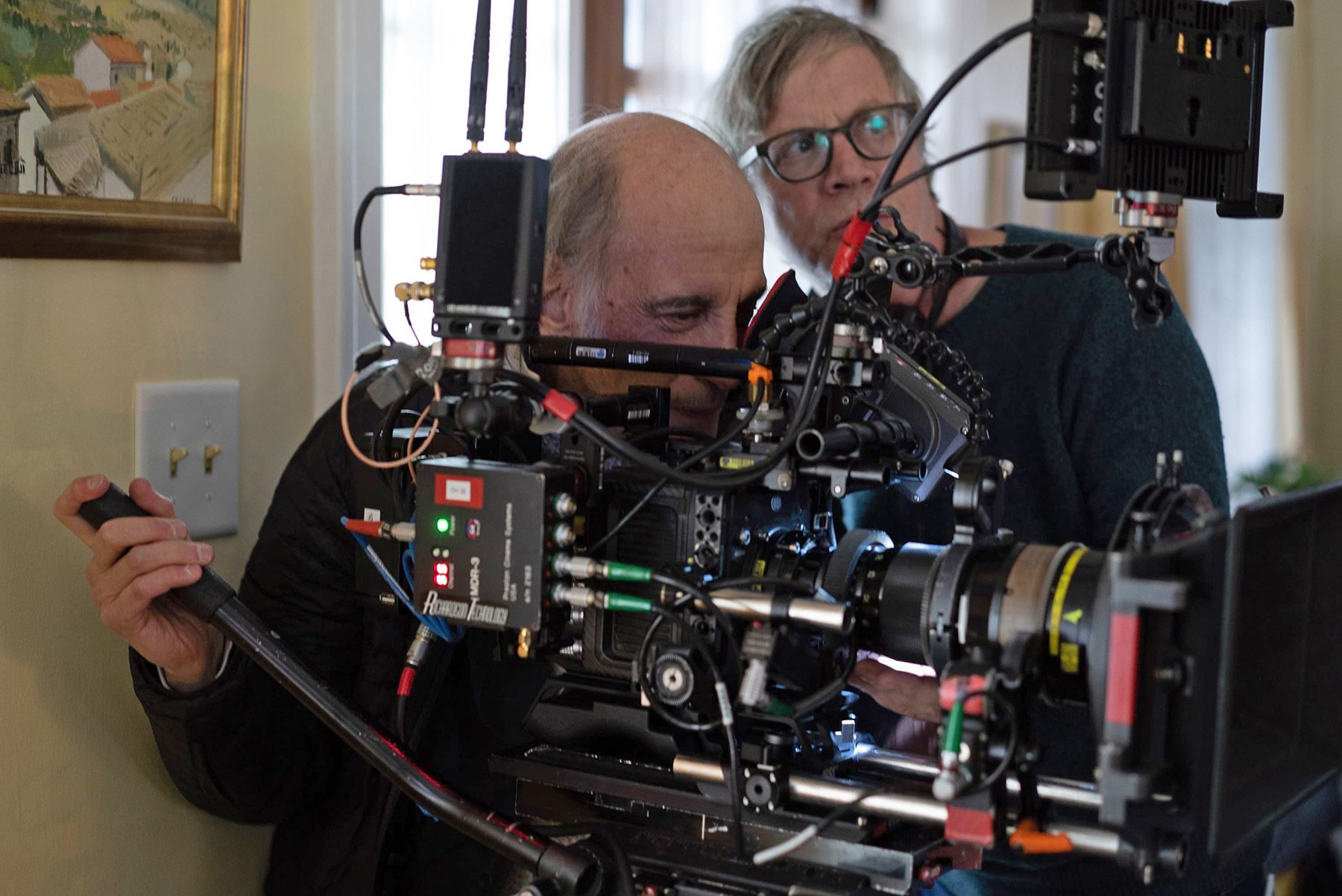

Edward Lachman, ASC and director Todd Haynes lend a cool, “contaminated” look to this reality-based thriller.

Unit photography by Mary Cybulski. All images courtesy of Focus Features.

Attorney Rob Bilott was on the way to a promising career at Cincinnati law firm Taft Stettinius & Hollister, where he was working for corporate clients. Living in his new suburban house with his wife, Sarah, and his growing family, he’d just been made partner and was planning his future when the direction of his life changed forever.

A West Virginia farmer, Wilbur Tennant, who knew the attorney’s grandmother, sought Bilott out in search of legal help with his grievance against chemical giant DuPont, which he believed was causing the deaths of his livestock. This was the beginning of the real-life story of a decades-long legal battle, which eventually became the subject of a New York Times Magazine piece by Nathaniel Rich, and is now the basis of the feature Dark Waters, directed by Todd Haynes and shot by Edward Lachman, ASC — whose frequent collaborations have included the films Far From Heaven (AC Dec. ’02) and Carol (AC Dec. ’15), and the miniseries Mildred Pierce (AC April ’11). Mark Ruffalo stars as Bilott in the production from Focus Features, which also stars Anne Hathaway as Sarah, Bill Camp as Wilbur, and Tim Robbins as Taft senior partner Tom Terp, the latter of whom, sometimes reluctantly, supported Billot throughout his long fight for justice and the truth.

Unlike Haynes and Lachman’s previous films, which are set in more distant periods and sometimes — as with the ’50s-era melodrama Far From Heaven — captured in a deliberately mannered and stylized fashion, for this project the filmmakers chose to work in a more straightforward, realistic style. Although this was a departure for the duo, the themes expressed in Dark Waters were quite familiar to both filmmakers.

“All whistle-blower films are very much about a process of discovery, whether they’re about journalists or lawyers... It’s not so much about what is discovered, as it is about the process of discovery and the effect of that on the characters.”

— Todd Haynes

As Lachman notes, the Oscar-winning film Erin Brockovich — which he shot for director Steven Soderbergh — depicts the journey of the relentless title character (played by Julia Roberts) as she battles the Pacific Gas and Electric Company, “another corporation guilty of caustic destruction of the environment and people’s lives.” And as for Haynes, Lachman points out, the film that established him as an up-and-coming director was Safe — a character study of a woman (Julianne Moore) whose life is laid waste by the debilitating symptoms of an unexplainable environmental illness.

In seeking a compelling cinematic language for Dark Waters, and for Bilott’s painfully protracted struggle to expose the malfeasance of an industry, Haynes found inspiration in whistle blower-themed movies, particularly the thrillers that director Alan J. Pakula and Gordon Willis, ASC filmed in the 1970s — stories, whether true as in All the President’s Men, or fictional as in The Parallax View and Klute, that follow their lead characters as they uncover increasingly frightening levels of corruption and modern-day horrors. “All whistle-blower films,” Haynes says, “are very much about a process of discovery, whether they’re about journalists or lawyers — or, as in Silkwood, about a woman who works in a plutonium plant. It’s not so much about what is discovered, as it is about the process of discovery and the effect of that on the characters.”

Dark Waters’ narrative follows Billot’s journey through his procedural research, and as the lawyer makes discoveries, Lachman points out, the audience shares in them. “One step leads to the next,” he says, “so we are putting the puzzle together, even if we don’t know exactly where it’s all leading.”

A sense of authenticity and an observational style was important to the filmmakers as they embarked on Dark Waters. Much of the film was shot in and around Cincinnati locations, where the actual events occurred over the decades — from the ‘70s through to the present. Haynes and Lachman also found inspiration in a number of still photographs in which the photographers avoided the stereotypical view of Appalachia, and instead depicted the people’s experience of rural life, and explored their subjects’ inner lives. Additionally, Lachman mentions photographers William Gedney, William Eggleston and Mitch Epstein, along with Tennessee-based documentary photographer Mike Smith, “who imparted a poetic sense of the commonplace in everyday life. For me, all of these images of suburban and rural areas present an unexpected beauty in an imperfect world, not just through a representational view but also a psychological one.”

The Taft law offices feature prominently throughout, and the production was able to shoot in the downtown Cincinnati skyscraper where the firm is still located — some scenes in the actual Taft offices, and others in a space several floors above that were undergoing renovation which, Lachman reports, worked perfectly for the production. A nearby house was used for Rob and Sarah’s home, and an abandoned farm in Colerain, Ohio served as Wilbur’s ill-fated West Virginia homestead.

Haynes and Lachman had initially wanted to shoot on film, as they had done for all their previous work (save for a couple of shots in Wonderstruck, which were photographed digitally for technical reasons). “Todd is always interested in the mechanisms that create the world we’re shooting in,” Lachman says. “This story is about contamination of chemicals and how they affect our lives.” The cinematographer relates this idea to the inherent chemical aspects of a film-captured image, which in turn leads to a discussion of Lachman and Haynes’ shared aesthetic appreciation for the way film negative creates colors, as opposed to the work of digital sensors.

“The depth of film grain, which is affected by the chemical process of developing, and the cross-over contamination of contrasting colors in the negative’s silver halides, bring attributes to an image that I find extremely difficult to create in digital capture,” Lachman says. And the fact that the story takes place over a time period starting in the 1970s “was another reason we wanted to shoot on film, the way it would have been seen at that time.”

“Using the higher EI also introduced some texture into the image, while blocking up the curve on the low end, which I feel helped to provide more of a feeling of film.”

— Ed Lachman, ASC

Skeptical producers required Lachman to shoot tests in multiple film and digital formats to support the filmmakers’ arguments that film would neither add cost nor slow down production. He shot the tests on Super 16mm and 35mm film, and in 2K large-format digital. “Unfortunately, word came down from the studio,” Lachman recalls, “that we’d have to shoot digitally, even though they saw our point, visually, and I had proved that it wasn’t more expensive or more difficult to shoot on film.”

Given the digital requirement, he chose Arri’s Alexa Mini. Both filmmakers acknowledge that with some help in post, they were ultimately able to come very close to what they’d intended to accomplish on film. (More on that below, in Designing a Film Look.)

Lachman shot in 2K with spherical lenses, capturing in Log C to ArriRaw and framing for 2.39:1. “Todd trusted that I could do something digitally that wouldn’t feel like a negation of what we wanted to do on film,” Lachman recalls. To that end, he endeavored to achieve some of the image qualities they sought by using older optics — in particular, Cooke Speed Panchros, Canon K-35s, and vintage zooms from Cooke and Angénieux. “The older glass was made with lead, and polished and coated differently than the glass made today,” the cinematographer says.

Adds Haynes, “We love film — there’s no way around that — as a starting point, regardless of the subject matter and the material. Ed and I have also been interested in ways of degrading the hyper-sophistication of lenses these days, even on film. We used Super 16 for Carol and Mildred Pierce, and Ed is great at going against the technology and introducing interference, so we don’t end up with some kind of ‘perfect’ clean image that neither of us is interested in.”

Once Lachman had committed to shooting digitally, he embraced many of the new tools that were available to him, and he reports having a great working relationship with DIT Maninder “Indy” Saini. “There are things I used to do with film stock that I implemented digitally,” the cinematographer says. “I controlled the [EI] rating on the camera and dialed in different color temperatures to control the look. I knew we could do a lot in the DI to bring back the highlights, but it also helped sometimes to shoot at a higher rating — 1,280 or 1,600 — rather than the native 800, which let us better hold highlight detail. Using the higher EI also introduced some texture into the image, while blocking up the curve on the low end, which I feel helped to provide more of a feeling of film.”

Production designer Hannah Beachler — whose work on Black Panther earned an Oscar, which she shared with Jay Hart — set about bringing character and a feeling of authenticity to the locations. Lachman always prefers to work closely with production designers and art directors from early on in the process. “I like to be involved in the colors and textures they use to paint and dress the sets,” he notes, “so I can coordinate my color temperatures and gels when filming.”

In the approach to imagery, Lachman notes, “I was looking for a way to feel the images becoming more ‘toxic’ and ‘contaminated,’ as it is for the characters. There is also an overall coolness in the film, literally in the weather and the environment, but also in the temperament and emotions of the story. The overcast mood of the daylight during the winter reinforces the psychology of isolation in the story.

“I used a warmer, tainted yellowish hue, motivated by practicals inside the law firm, hospitals and various people’s homes, that would offer a contrast to that overarching coldness,” he continues. “We [also] wanted to show that there was some ‘invasion’ between the exterior and the interior.” For example, he notes, the yellow-greenish hue from the practicals in the law offices “play against the coolness coming from outside the windows. Also, when Rob visits his grandmother’s house, there are little candelabra lights over her table that provide a sense of warmth in the scene, which is surrounded by fading winter light.”

Independent of those psychological elements, Lachman explains, “I always try to use contrasting colors within the frame because I feel the viewer’s eye loses the ability to see the subtlety of just one color.”

The law offices, Haynes says, are “such an amazing location. We shot in both the real Taft law offices, and also built our conference room and Rob’s office 10 floors above the real Taft offices in the same building.” All of this, Haynes adds, played perfectly into the kind of cinematic storytelling that Pakula and Willis achieved in those paranoid thrillers of the ’70s.

“The views that you saw out the windows, with the Cincinnati architecture, are partly blocked, which limits the depth of your visibility and creates a sense of power and curiosity about what is hiding behind those windows,” Lachman notes. He adds that the “frames in the Taft offices — in the hallways and the windows looking out, a repeating theme within the architecture — form a sort of minimalism that echo the negative space used by the painters we looked at for inspiration: Giorgio De Chirico and Rene Magritte, who used challenging juxtapositions of objects and space, provoking a hidden feeling of power.”

When the filmmakers first scouted, the offices had older Cool White fluorescent tubes that read green-yellow — which, as noted, appealed to Lachman — but before shooting commenced, the building had started the process of switching to newer LED lighting units. Luckily, the cinematographer was able to convince the facility to keep the older tubes until the shoot was over.

Gaffer John DeBlau, who has worked with Lachman for decades (AC Nov. ’19), explains that much of the lighting in the offices involved controlling the windows — either by gelling them with ND or using existing shades — and making use of the fluorescent lighting in the offices, and then building up the levels inside to supplement. “Most of the offices were a mix of daylight and the Cool White fluorescents that have a bit of green in them,” DeBlau says. “We’d bounce HMIs inside during the day. At night we’d switch to [tungsten] Source Fours gelled with Half CTB and Plus Green to enhance the quality of light that was there.”

The production found many uses for portable, battery-powered Astera LED units. “You can make them any color and just stick one on a bookcase, bounce it off the ceiling, or use it for more direct light,” DeBlau explains. “You put it where you need it and you’re good to go for hours!” Adds Lachman, “I really liked those lights. If I needed a little fill or an edge, we could just dial in what we wanted it to feel like — if it’s more daylight, fluorescent or tungsten.”

“We even used them underwater,” DeBlau enthuses, referring to Dark Waters’ opening, in which a group of unsuspecting teenagers take a swim in a highly polluted river. “One of my guys was out there, soaking wet with a couple of these Astera lights that we wrapped in plastic because they’re not waterproof. But we sealed them tight enough, stuck them under the water, and they were fantastic!”

Bilott’s house, as seen throughout, tells a subtle story on its own. “So much of what you understand about Rob and Sarah’s world is built into the location,” says Lachman. Haynes adds, “They had basically invested in a new neighborhood at the beginning of his becoming a partner. They’d expected that they would probably grow out of it, as he moved up the corporate ranks as a partner. That didn’t happen. He basically never had another corporate client for the rest of his career. This case dominated everything in his life.”

Beachler, through the design, and Lachman, primarily using composition, demonstrate the constriction of this dream as the conflict with DuPont goes on, and Rob’s children get older. Scenes become more cramped; what seemed spacious at first now feels claustrophobic. It’s the kind of detail Haynes uses frequently — something the viewer doesn’t need to register consciously, but which provides resonance.

Since the feature was shot during winter, and much of it takes place in overcast conditions, Lachman approached lighting day interiors in the house to match what was outside. The cinematographer and crew therefore sometimes directed open-faced 4K Arri X HMI fixtures through Full Grid Cloth directly into the house, and other times bounced that light in with 8'x8' Ultrabounces — in either case resulting in the illumination from the exterior becoming diffused and falling off inside.

For Lachman, a great deal of the power of Dark Waters’ visuals is ultimately derived from shooting in many of the actual locations where the events took place. “Look at that courtroom in Hamilton, with that mural of Daniel Boone!” he attests. “I mean, you couldn’t have imagined that would really be there. To me, that’s why I love shooting a film like this, because the reality is the fiction, as the fiction becomes the reality.”

TECH SPECS

2.39:1

Digital Capture

Arri Alexa Mini

Primes: Cooke Speed Panchro, Canon K-35

Zooms: Cooke, Angénieux

Designing a Film Look

I’ve had the pleasure of working with Ed Lachman, ASC and Todd Haynes on Wonderstruck and several re-mastering projects. Dark Waters is a bit different from their previous films because of its gritty fact-based story, though there is also a definite, carefully thought-out look and color palette to the images.

To start with, they shot with Arri Alexa Minis, but they’d wanted to shoot film. So we designed a specific show-LUT in preproduction with that in mind. We didn’t use Arri’s K1S1 color science; instead, we customized more of a film-print emulation LUT that we tweaked to bring more of a cool blue cyan bias into the shadows, and also rein in and bend some of the blue hues. They could treat this as their “film stock” while they were shooting, which I know was something they found to be helpful.

When we started work on the final grade in [Blackmagic Design DaVinci] Resolve, we stayed away from most of the bells and whistles, using “printer light” and contrast controls to affect the overall look and color temperature. If the blacks in a scene got softer or milkier based on exposure, as would happen with film negative, we didn’t fight that — we embraced it.

We further enhanced the filmic look with LiveGrain, which I’ve found to be a very powerful tool. I’ve worked with a lot of different methods of adding grain effects, and this just feels more like it’s adding a three-dimensional organic texture. You’re compositing three different grain elements into every shot, with the grain response based on where the exposure of a part of the frame sits. The idea wasn’t to draw attention to the grain, but to add the kind of texture that would have been present if they’d shot on film. You don’t have to see it. You feel it.

After we got all the shots balanced, Ed and Todd gave me a few days to go in and do a bit of a technical pass, and then they came back and continued to take more of a fine touch to parts — dodging and burning, maybe adding a grad to the sky or pulling a key — always making sure to keep everything within the feel of the photochemical world. We enhanced some of the yellows and greens in the law offices, and for the rural farm scenes we pushed the blueness pretty far to emphasize the cold, stark, overcast environment.

It’s always inspiring working with Ed and Todd. They both have such strong visual sensibilities and they are relentlessly passionate about the work.

— Joe Gawler, Senior Colorist,

Harbor Picture Company