Photography for Das Boot

“It was not only to become the most expensive German film ever made, but also technically the most complex and elaborate.”

This article was originally published in American Cinematographer, December, 1982.

The film Das Boot is based on an actual experience by Lothar-Günther Buchheim, who wrote the book by the same title. It is about the experiences on board the German U-boat U-96, while on patrol in the Atlantic Ocean during 1941, from the point of view of its German crew.

Already in 1976 this project was planned as a feature film with U.S. participation. The director was to be John Sturges at first, and later Don Siegel. Robert Redford was originally cast in the role of the U-boat commander. The building of the boat had already been commissioned when unexpected differences between various American screenwriters and Buchheim caused the project to collapse. Finally, in 1979 Bavaria Studios again created the opportunity to realize this production as a purely German undertaking by making the feature film in combination with a simultaneous five-part television series. As director, Wolfgang Petersen, who also wrote the screenplay, was chosen. It was not only to become the most expensive German film ever made, but also technically the most complex and elaborate.

“Glamour and obvious technical slickness had no place in the movie. Rather, absolute authenticity was required, above all in the lighting.”

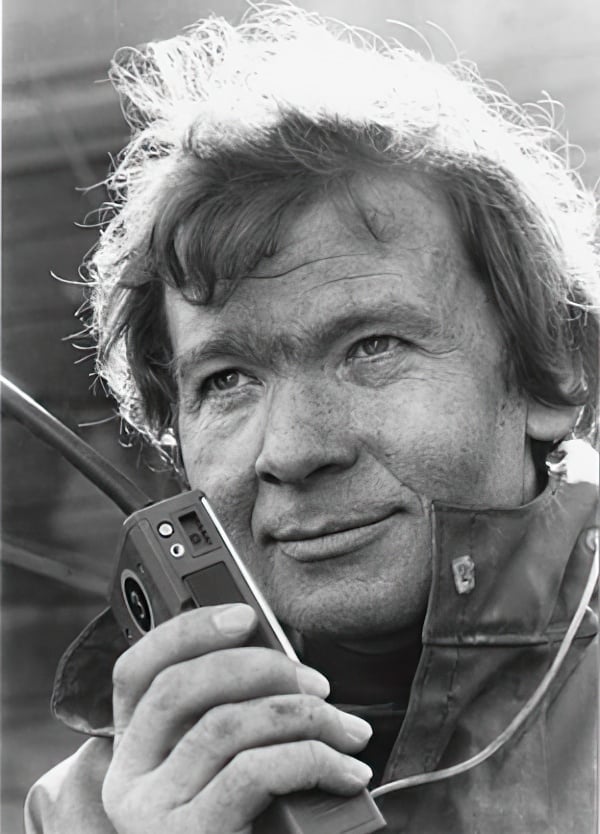

As director of photography, I was confronted with a new problem, never before encountered: the enormously confined interior of the U-boat. I further had to deal with the resulting restrictions in lighting, the matching of various scale models both above and below water, storm scenes and explosives, a large number of optical effects, and the development of special camera systems and mounts.

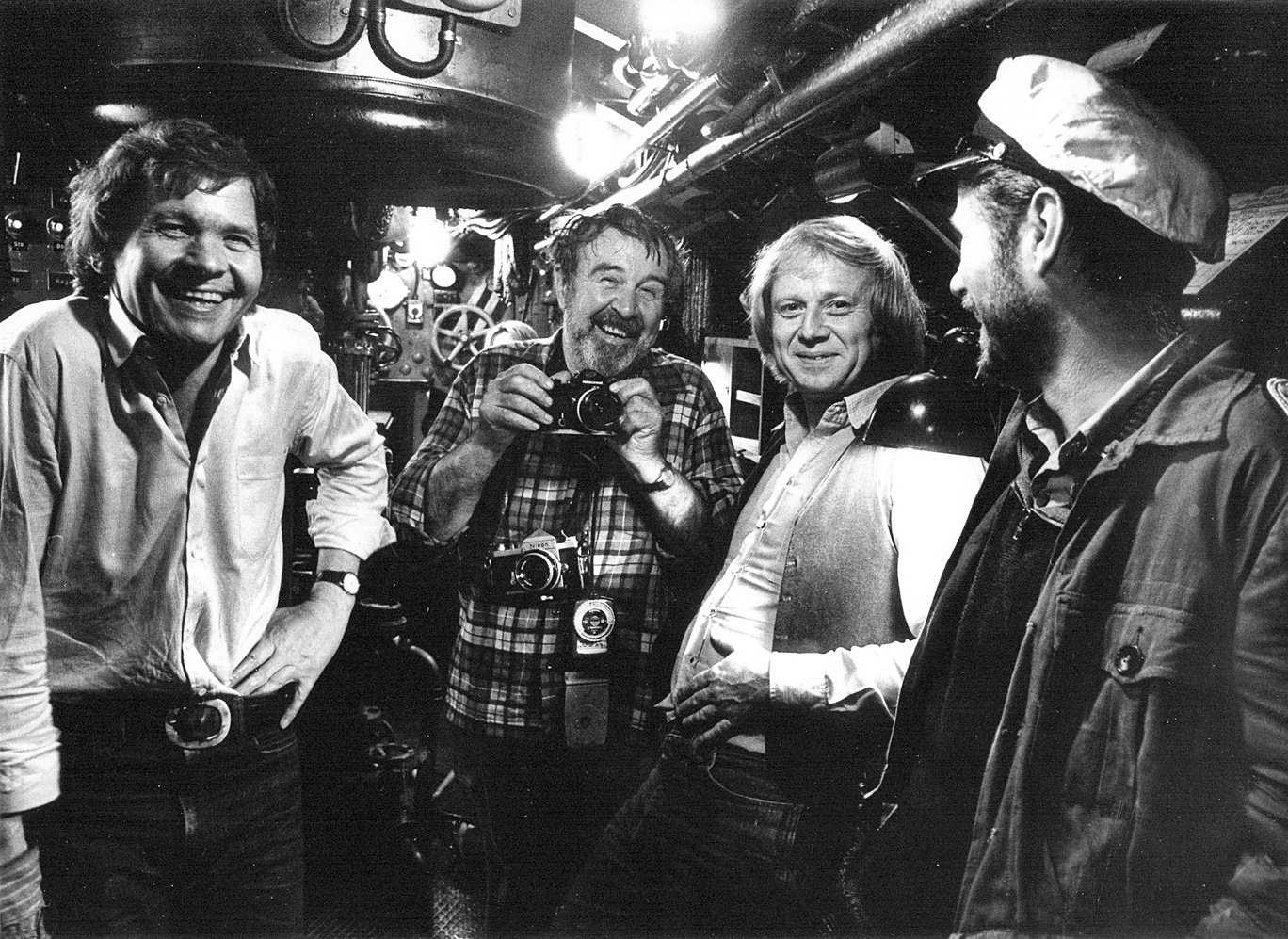

Das Boot is not a war movie, but rather a movie about people during war as seen in the microcosm of a U-boat. It tells the story of young men who are still half-children, adventurous, misguided by fascist propaganda, fascinated by technology and almost without exception volunteers, unknowns. For this very reason there are no stars in this film. A large part of the crew was cast with lay actors, and only the important parts were cast with professional actors. Indeed, only the part of the commander was cast with an internationally known actor, Jürgen Prochnow. Glamour and obvious technical slickness had no place in the movie. Rather, absolute authenticity was required, above all in the lighting. The camera had to subject itself to the same confines as the actors. It had to play the role of an observer, i.e. no removable walls, cranes or dolly tracks, etc. The requirement of extreme mobility within the narrow confines of the boat would not even allow the use of a “Steadicam.” It had to be a hand held camera!

At first, this presented a major problem. Did not a big expensive movie have to be especially perfect in its technical aspects, without the minor flaws which one accepts very often when there is a lack of time and budget? How does hand-held camera work and almost no lighting fit into this concept? But I have long learned that a major ingredient of our profession has to do with guts, and this was ultimately what helped me make the decision. The documentary style of the film also led to the choice of the negative we used, which was Fuji 8517/8518 with its subtle colors and contrasts.

The main character in the film is most certainly the boat itself. However, none of the VIIC U-boats had withstood time since the war in good enough condition for filming of all interior and exterior scenes. Rolf Zehetbauer, the Oscar winning set designer, therefore created a whole armada of U-boats authentic down to the most minute detail. He built one interior model as well as a complete exterior in the original size (240' long). In addition a 40', 1:6 scale model, submersible and remote controlled was built for running shots in the ocean, during the storm, and for front projection plates. One 20', 1:12 scale model was built for all underwater filming and, finally, a 10' model (along with various destroyers, tankers and other ships) were made for special-effects photography.

After a long period of pre-production, shooting began on the North Sea Island of Helgoland in March of 1980. Here we expected to shoot all the high speed running shots with the 40' boat, and all storm scenes. For the front-projection plates we needed the front and rear end of the boat within the shot so that we could combine them later, in the studio, with the bridge and the actors on it. The small scale model of the boat thus required high-speed filming in the range of 50-100 frames per second. Magazines had to be of 1,000' capacity as the boat had to return to its harbor and be lifted out of the water by crane for each magazine change. Unfortunately, there was no existing 35mm underwater camera that could do all of that, so we had to build one ourselves.

Gerhard Fromm developed an adapter which allowed us to use the coaxial 35BL magazines on the Arri 35 III. This kept the camera and the underwater housing, which he also created, very compact. Naturally, all functions were remote controlled by radio. Two such cameras were mounted on the 40’ model which, considering the impact of the waves, was not a simple task especially since for front projection we could not have any image vibration.

“The narrowness inside the boat is hard to imagine. Here, during the war 50 people had to live, work and fight for months at a time. This is what now also awaited us.”

For the storm scenes we filmed in actual conditions with wave heights up to 15'. The boat was extremely seaworthy and even though it was submersed for up to 30 seconds, it always emerged in the correct position. All of that with big cameras mounted to its sides! As you might imagine, the tension was great after every shoot until we got the report back from the lab that everything was okay, or, as it also happened, that it was not. For the camera to tolerate these extreme stresses, with 1,000' magazines and up to 100 frames per second, with waves pounding it like giant hammers, I can only congratulate Arriflex and, of course, Rolf Zehetbauer, who built the boat.

A further problem arose with the long shots where we used remote controlled dummies on the bridge instead of actors. The elevation of the camera over the waves had to be the same as the elevation of the bridge of the model boat over the water, i.e. 1' to 2' above sea level. During the storm scenes therefore, the camera as well as the crew was constantly swamped by waves. To accomplish these takes, a large hole was cut into the side of the camera boat. With the camera looking through it, lying on the floor of the boat [first assistant] Peter Maiwald and I, both in diving suits, life vests and strapped down, were constantly gasping for air in between the waves. During all this we had to keep frame on the model U-boat using a focal length of around 200mm. A considerable artistic feat, but not unusual in our profession; and this was only preproduction.

An additional problem encountered was the constant splashing of the front glass of the cameras. Normally one could use a rain deflector, a high speed rotating glass disc which throws the water off through centrifugal force. However because of the impact of the waves these deflectors were immediately destroyed, so that only one old remedy was left. The front glass, on the outside, was coated by rubbing it with a green apple. This reduces the surface tension of the water for some short time so that it can run off without causing any bubbling or tracing. By the way, this can also be done directly on the front surface of a lens. There was also the problem of condensation on the front glass which, in water this cold, cooled very quickly on the inside and had to be heated or pre-heated. So, as with almost every film, there were surprises and new opportunities to pay one’s dues.

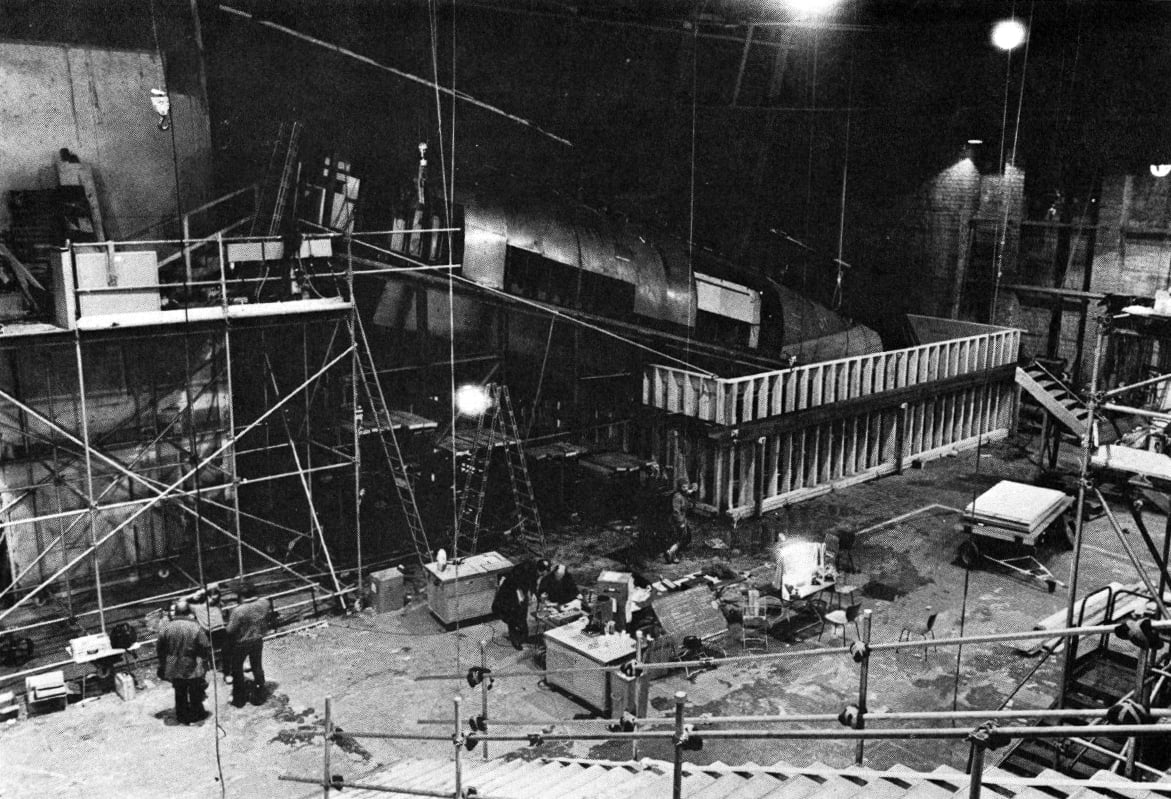

They were not easy weeks on Helgoland; but the results were important as these shots were the highlight of the film. In earlier American screenplays these scenes didn’t even exist because neither John Sturgess nor Don Siegel considered them possible to make. In July of 1980, finally, the main part of the production with actors started in Studio 4 and 5 at Bavaria Studios in Munich. There, the interior of the boat was our home for the next eight months.

The set was a reconstruction of the interior of the boat, made to actual size and accurate to the minutest detail. It was 240' long and varied between 8' and 15' in width. The construction was of steel, sheet metal and wood, and it consisted of five segments representing the five compartments of the boat which were separated by the typical round doors with heavy steel locks. Most of the components and interior apparatus were gathered together from museums around the world. The narrowness inside the boat is hard to imagine. Here, during the war 50 people had to live, work and fight for months at a time. This is what now also awaited us. The passageways in the boat were so narrow that only two people could barely pass each other. In this environment, without removable walls, we had to find camera angles.

All natural motions of the boat had to be duplicated with the entire set. For this, the entire set was mounted on a 17'-high platform with a hydraulic system to move the boat on its longitudinal and perpendicular axes up to 40 degrees. With this all motion, such as storm scenes, diving, etc., could be simulated. A digital computer allowed this platform and its motions to be pre-programmed. After some initial difficulties this system functioned so well that the first seasick members of the crew and cast left the set.

How can the viewer be made to feel these motions since a U-boat has neither windows nor an exterior point of view? Only the camera could relay this feeling. To convey the motion of the boat, the camera had to remain reasonably stable on an imagined horizon, thus all movements of the set and actors would be seen as deflections from the natural horizon. This would have actually required the use of a crane or similar stable platform which could have entered through an opening into the boat from the outside. Due to the physical confines, however, this was impossible. On the other hand, the camera also had to be extremely mobile in order to move around obstacles and people inside the boat. How could these two seemingly paradoxical requirements be met?

The solution was a gyro-stabilized hand-held camera, a similar version of which I have used for many years. In Germany, the separate function of the camera operator is nearly unknown, and most cameramen operate their own cameras. Therefore, it was my job to be adept at controlling the “stubborn character” of a gyro which resists attempts to have its axial direction moved in space. As with a Steadicam, practice is at least as important for successful results as the unit itself. For this film, two stabilizers were crossed with their effective axes so that all motion around the optical axis, i.e. the imaginary horizon, was controlled by both stabilizers, whereas the other two axes, i.e. pitch and pan, were controlled by only one gyro. (The Kenyon stabilizer is an electrically driven, high speed gyro operating in a vacuum housing). Fortunately, due to the noise of the hydraulic platform we could not go for original sound anyway, so it allowed me to use a lightweight camera.

The lightest one, the Arri IIC, has only a horizontal finder system at the lens axis, and in many cases I would need a low camera position with a finder that allowed viewing from the top. Based on these requirements and with my input, Arnold & Richter, manufacturers of Arriflex cameras, virtually built a new camera for this film. Using the Arri IIC movement, the entire movable finder system of the Arri 35 III, and the new smaller central housing with only one fixed lens receptacle, they created the ideal MOS hand held camera. With the finder extension I was able to accomplish low camera angle shots virtually starting at floor elevation, but with the operator standing almost erect. Together with a remote controlled focusing device which I designed with the help of Alfred Chrosziel, the requirements as far as the camera was concerned, had been fulfilled.

By now the new problem was that the hydraulic platform was functioning so flawlessly that actors and crew had a hard time keeping their feet on the floor during storm scenes. How could I stabilize myself holding the camera during a shot without breaking every bone in my body? So, back to more practice, and a crash helmet, guards on arms and legs with bandages in between. Soon I looked more like a football player than a cameraman, but I was getting the situation under control. I also had to get used to keeping both eyes open while shooting so I could concentrate on the composition in the finder as well as anticipate my surroundings better.

“‘Grab the camera and run.’”

The most memorable camera move of the whole film, is, of course, the continuous run through all five compartments of the boat, through all airlock doors, without a single cut. I have heard an unending number of speculations about how we accomplished it. The explanations range from retractable rails to overhead cable runs. Also mentioned was the possibility that the camera was handed from person to person, from compartment to compartment. The true explanation is in fact the simplest, but nobody had thought it possible, including the director and myself. After we had seen the interior of the boat for the first time, we had an instant desire to have one long continuous shot that would go the full 200’ length of the interior of the boat. This thought was so powerful that we could never quite dismiss it.

As I got more and more familiar with the interior of the boat and the controlling of my special camera, the thought re-surfaced and we made our first running attempts during other scenes. First only through one of the air locks and slowly. And then, after a while, suddenly it worked. As time went on we got braver and faster, and after two months of shooting inside the boat the time had come to revive the old idea. The procedure was to “simply grab the camera and run.’’ Sometimes we cleared obstacles by fractions of an inch, sometimes we didn’t. But all the scrapes and bumps are healed now, and the Arriflex also once again withstood the punishment without major complaints. First I had tried to mark my steps precisely, but that never worked. Only after I started to run without thinking and planning did it work out properly. This surely had lots to do with instinct and concentration, but I’m sure equally as much with desire.

The limit to hand holding the camera finally had to be recognized during the scenes which included depth charge explosions and extreme storm situations. As the actors on the set, on top of the platform, held on for dear life (big stars would not have subjected themselves to such torture) the cameramen had to think of new approaches. By now, the set had been separated so only the backgrounds were mounted on the platform which, with this reduction in weight, could accomplish more violent movements. The camera was mounted separately in front of the set, also on the hydraulic platform but able to pan. It was horizontally stabilized through a long pendulum that reached down to the studio floor. With the pendulum the camera platform could be set in motion countering that of the main platform, thus exaggerating the apparent movement of the boat. These scenes were shot with multicamera set-ups since the action within the boat was not totally predictable and changed from take to take.

The same set-up was used for depth charge simulation. Here the entire platform was allowed to actually bounce on its support pillars with a full force so hard that the welds on the set started to break. It was an inferno also in terms of noise. To enhance the effect, tripods were mounted on rubber elements which prevented the most severe shocks from reaching the camera but made them vibrate at a different frequency than the set, thus adding to the effect of the explosions. Video adapters on all cameras allowed us to judge individual takes instantly. In the middle of this already crazy environment, our special effects team under Charlie Baumgartner created fire, explosions, and gushing water leaks, one after the other.

Very difficult and very trying for both crew and cast were the sequences in which the boat hits bottom off the coast of Gibraltar and lying on its side, starts to take on water. For this, the set was moved to a large tank which was slowly filled with water. Water spouted and gushed through all openings, and the actors spent the next few weeks up to their necks in water, and unfortunately, the camera crew as well. The Arriflex also got more than one involuntary bath, since the only thing that could be done to protect it was to wrap it in a plastic foil. By this time, everyone on this film, whether in front or behind the camera, started to understand the stress, the fears, and the claustrophobic feeling these crews must have endured during their missions.

“The various colors of the interior lighting were not our choice... They were original and had distinct functions subservient to the needs of the boat.”

Important to the filming of Das Boot was the design of proper lighting. Within the boat, we worked almost exclusively with the original light sources according to the original lighting plans of this type U-boat. Of course, those were designs specifically in line with the boat’s limited energy supply while operating underwater. Each source was very meaningful in its specific placement. This original, basic lighting plan was only modified to the extent that we equipped the sockets with, appropriately higher output sources. Only during close shots and in special situations did we resort to additional lighting.

Whenever the script called for electrical failure, the flashlights were activated. For this we had built special flashlights with 70w quartz bulbs and replaceable nickel cadmium batteries. Here again we used no additional lighting, and the light cones thrown by the flashlights in the expended air of the boat interior added to the dramatic look. The various colors of the interior lighting were not our choice either. They were original and had distinct functions subservient to the needs of the boat. Red was the light for general alarm as well as the night light when the tower was occupied. (Eyes adapt quicker to darkness when they come out of red light). Blue was the light used for electrical failures and as night light in the crew quarters of the boat. Smoke, and its related difference in colors, was also a functional part of the design, such as the exhausts in the machine rooms, the sticky used-up air in the crew quarters, or the smoke from various fires.

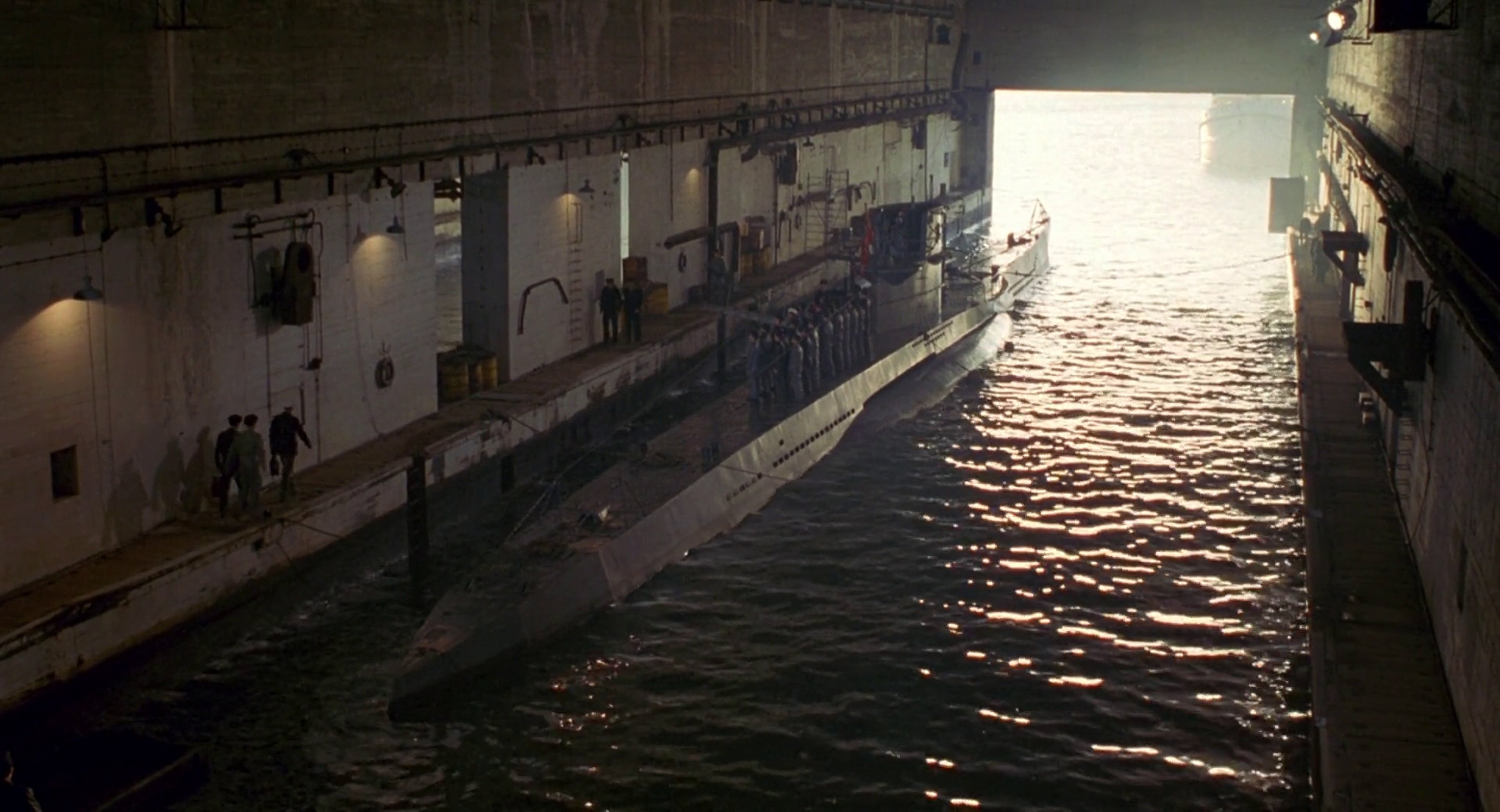

Even the longest schedule in the studios ends eventually, and next were the exteriors to be shot in La Rochelle, France. Here, the “big boat” awaited us, also a creation of Rolf Zehetbauer, true to the original exterior and 240' long. Of course this was only a U-boat in its overwater structure, and the entire set was supported by a metal frame mounted on floats driven by three engines with a total of 800 horsepower. With this boat we were planning to shoot the opening scenes in the U-boat bunker, the shots in which the boat leaves its home port, and all exterior boat scenes involving actors during calm sea conditions. Finally, we planned on shooting its homecoming and subsequent sinking when it was hit by bombs shortly before entering the safety of its bunker. Six camera crews and more than two tons of explosives gave the boat its final send off to the bottom of the Port of La Rochelle, which now looked as it must have looked 35 years ago during the war.

“Nothing was easy on this film.”

Unfortunately our film boat experienced a similar fate in that it broke up and sank in a storm. Luckily this happened during the night and nobody was on board. However, because of it many of the scenes which were to be filmed on the open sea now had to be moved back into the studio. There, a second conning tower with command bridge had already been rigged in front of a 70' front-projection wall. Nothing was easy on this film. For these shots in the studio, the bridge was inundated by huge amounts of water coming from a special chute in the studio ceiling, as well as from pumps and firehoses from all sides. The actors on the bridge literally had more water than air to breathe. The front-projection screen behind the bridge, however, had to be absolutely dry during all of this. It therefore had to be far behind the set, which created problems with depth of field. There, Fuji 8518 with its 250 ASA rating, allowing for the extra stop, was the salvation. Use of indirect lighting was also made possible by this.

Most difficult was the timing of the water effects. Each wave on the background projection had to continue to the foreground in exact sequence without anyone in the studio having the benefit of seeing the background. To time this properly, we had set up a large clock with a second hand, and it marked the timing of each water effect. The clock was coupled with the projector in both forward and reverse, and the video adapter on the Arriflex camera was able to show us the combined results.

In many of these shots the boat is a combination of foreground set and background projection. The bridge with the actors, for instance, stood in the studio, whereas the stern or stem of the boat was projected from footage with the miniatures shot off Helgoland Island. So that the composites of the shot did not move in relation to each other, the camera had to be mounted in a stationary position. However, since a boat in a storm is not stationary we had to give the illusion of motion again once the set was combined with front projection. To do this we designed a support for the front projection camera to enable it to be moved on all three axes, including around the optical axis. All of it, of course, had to remain in the nodal point. With the use of the video finder, the camera could thus be moved freely to follow the motion of the horizon in all directions. The result was a boat moving naturally in the waves, as if it were filmed from a helicopter. All background plates were done in 35mm full frame; a larger format [such as VistaVision or 65mm] was unfortunately not available. It is a tribute to the precise and excellent work of Bavaria’s laboratory, that in spite of it one cannot tell that the backgrounds are already second generation.

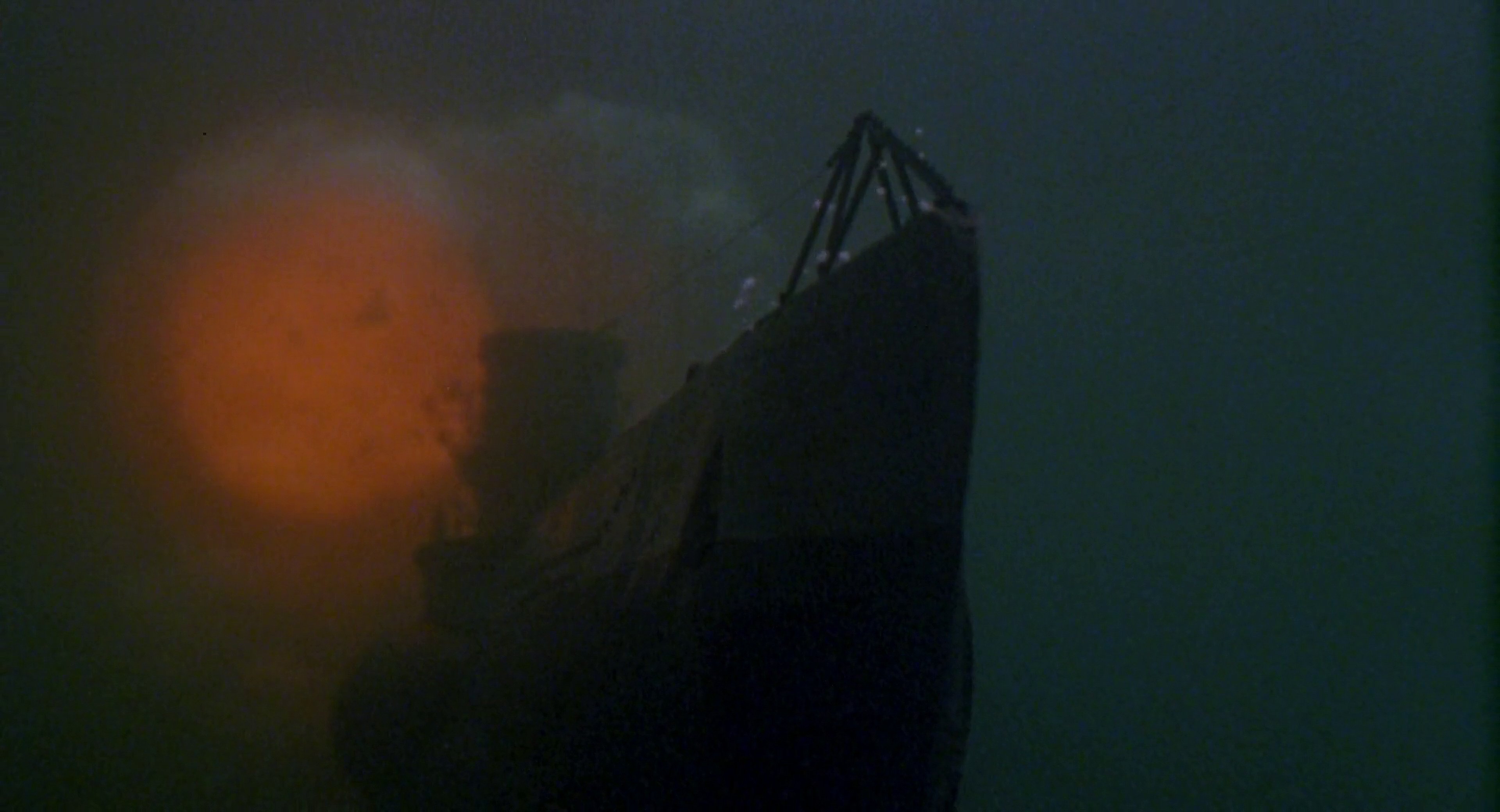

In the meantime, at Bavaria Studio’s tank the 20' model built by Hans Nothoff was being readied for all underwater work. Here too we had to deal with many difficult problems because of the complex movements of the boat. Egil Woxholt, BSC, with his crew, had to work underwater on tracks and with a jib arm. Again with the video finder image I was able to coordinate this from above the surface. An added problem here was the fact that the underwater visibility had to be coordinated with the 1:12 ratio of our model boat. This resulted in an 8' to 10' visibility for our crews which made working extremely difficult, but resulted in a realistic visual scale conveying the size of the boat accurately. At the same time, Ernst Wild was shooting all the miniature special effects with our smallest boat model, the 10' one. He generated all the scenes in the Port of Vigo, the attack on the convoy, the burning tanker and its shipwrecked sailors as well as the dramatic run through the straits of Gibraltar and the attacks on the boat. Finally, at the very end we shot the opening scene of the film, the celebration in the bar the evening prior to their mission. This was shot in the studio and was perhaps the only scene in the entire movie which we were able to film with conventional approaches, and without all the difficulties and problems that followed us through 18 months of production.

Das Boot was the largest, most expensive, and most complex film ever made in Germany. Nobody believed in the beginning that it would be possible. Since then, of course, the film has had tremendous success throughout the world, and it has received Germany’s highest film award for 1982. Individual awards were given for directing, for camera, and for sound effects. The film’s success is a tribute to all those who worked on it: To Bavaria Studios in Munich for their technical support and the professional and enthusiastic work of its crews; to the actors who accepted the most difficult conditions, yet never lost their spirit of cooperation; to the director, Wolfgang Petersen, whose enthusiasm and ideas carried everyone; the producer, Guenter Rohrbach, head of Bavaria Studios, who never lost his confidence no matter how trying the situation, and to Arnold & Richter for building a most remarkable Arriflex camera.

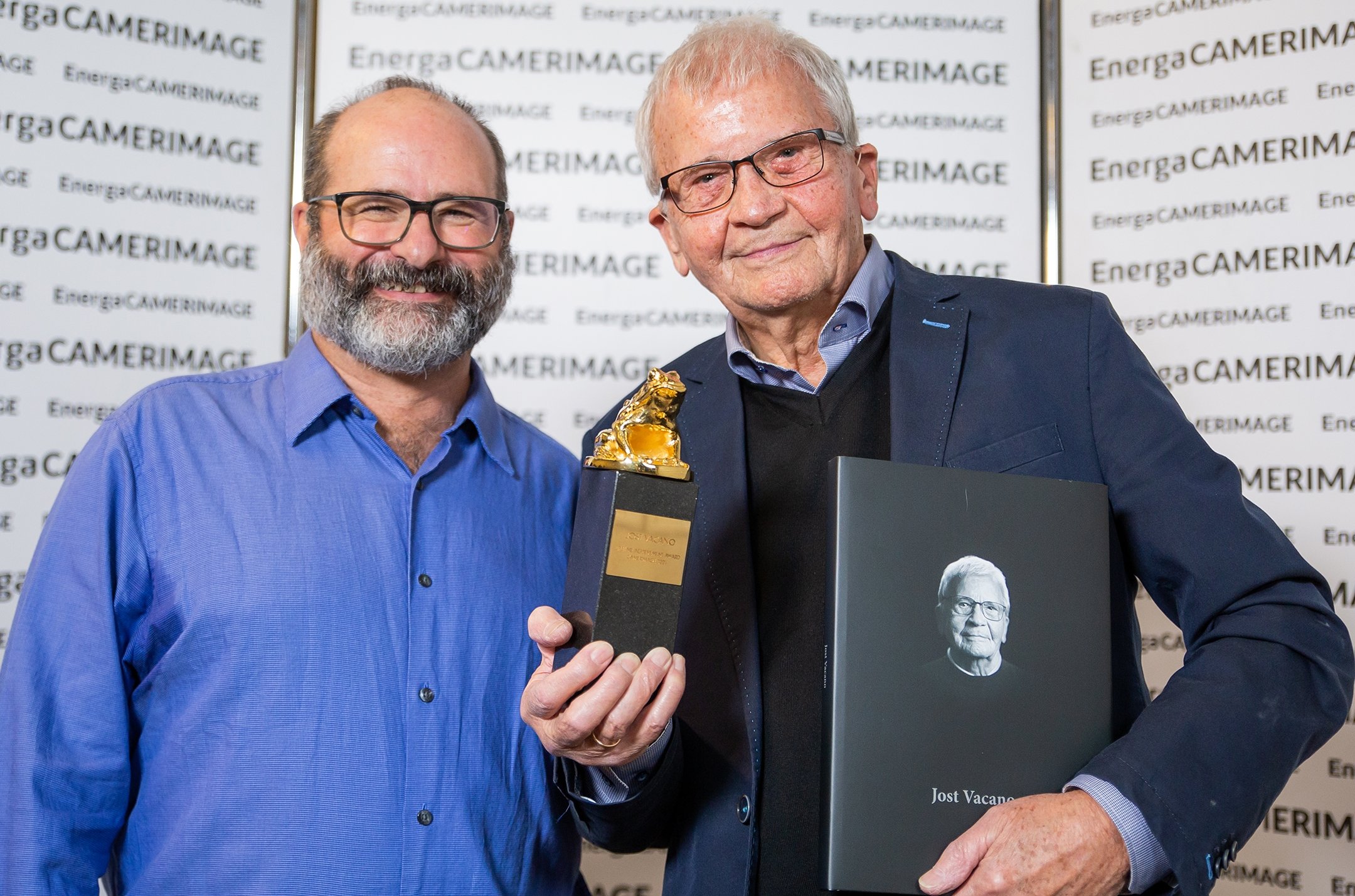

Vacano earned an Academy Award nomination and won the Bavarian Film Award for his camerawork in the picture.

He was invited to become a member of the ASC in 1991.

Vacano’s other feature credits include Spetters, Soldier of Orange, The NeverEnding Story, RoboCop, Total Recall, Showgirls, Starship Troopers and Hollow Man. He was honored with the Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2022 Camerimage Film Festival.