Empire of Light: Theater of Dreams

Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC reteams with Sam Mendes to help the director tell a deeply personal story.

Empire of Light follows the plight of a lonely, middle-aged woman working in a faded movie palace on the English coast in the 1980s. Superficially, this feature might appear to be a less taxing production challenge than Sam Mendes’ last collaboration with Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC — the Academy Award-winning World War I drama 1917 — but the filmmakers insist that it wasn’t.

Deakins explains that because 1917 was designed to look like a single continuous shot, it required several weeks of meticulous prep, and “by the time we came to shoot, it was fairly straightforward — there weren’t any surprises. But with a film like Empire of Light, you’ve never got enough money and time, and you’re at the beck and call of location problems and traffic control. Plus, we still had the problem of Covid-19.”

Mendes adds, “Empire of Light is a very still, deliberate and composed film … [so] Roger and I were debating how to shoot scenes in a more conventional way [than on 1917]. We didn’t have all that time to rehearse with the camera, so we were seeing things [on set] for the first time, which is normally how you make movies.”

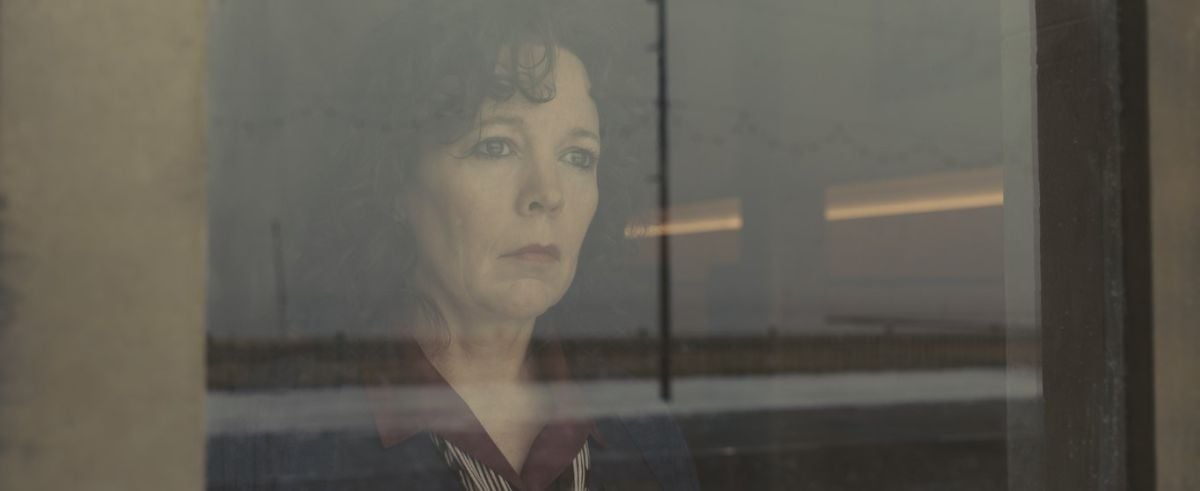

In writing the script for Empire of Light, Mendes based the main character, Hilary (Olivia Colman), on his own mother, who raised him as a single parent and suffered from a mood disorder. Hilary’s mental struggles are revealed gradually as she embarks on an affair with Stephen (Micheal Ward), a new, younger co-worker at the movie theater.

Mendes knew Deakins would relate to Empire of Light’s setting, given that the cinematographer grew up in Devon, England — a small coastal town similar to Margate, where the story is set. “That Roger loved [the script] was especially meaningful to me, because that world is familiar to him,” the director says. “We’ve had a wonderful run [working on] movies of all sorts, and we had a great experience on 1917, which brought us even closer together, collaboratively. I value his opinion not just as a cinematographer, but as someone who’s been part of some of the great films of the last 30 to 40 years.”’

Working with Mendes’ shot list, the collaborators’ typical approach is to offer their respective takes on the scene at hand and then come to an agreement. “Sometimes Roger’s take and mine are exactly the same, and sometimes they’re quite different,” Mendes says. “When they are different we debate the difference, and we either find a middle ground that pleases both of us, or one of us concedes defeat and accepts that the other person’s idea is better.” With a laugh, he adds, “Often, Roger’s idea is better. He has an unerring instinct for composition and the way the camera moves in concert with character.”

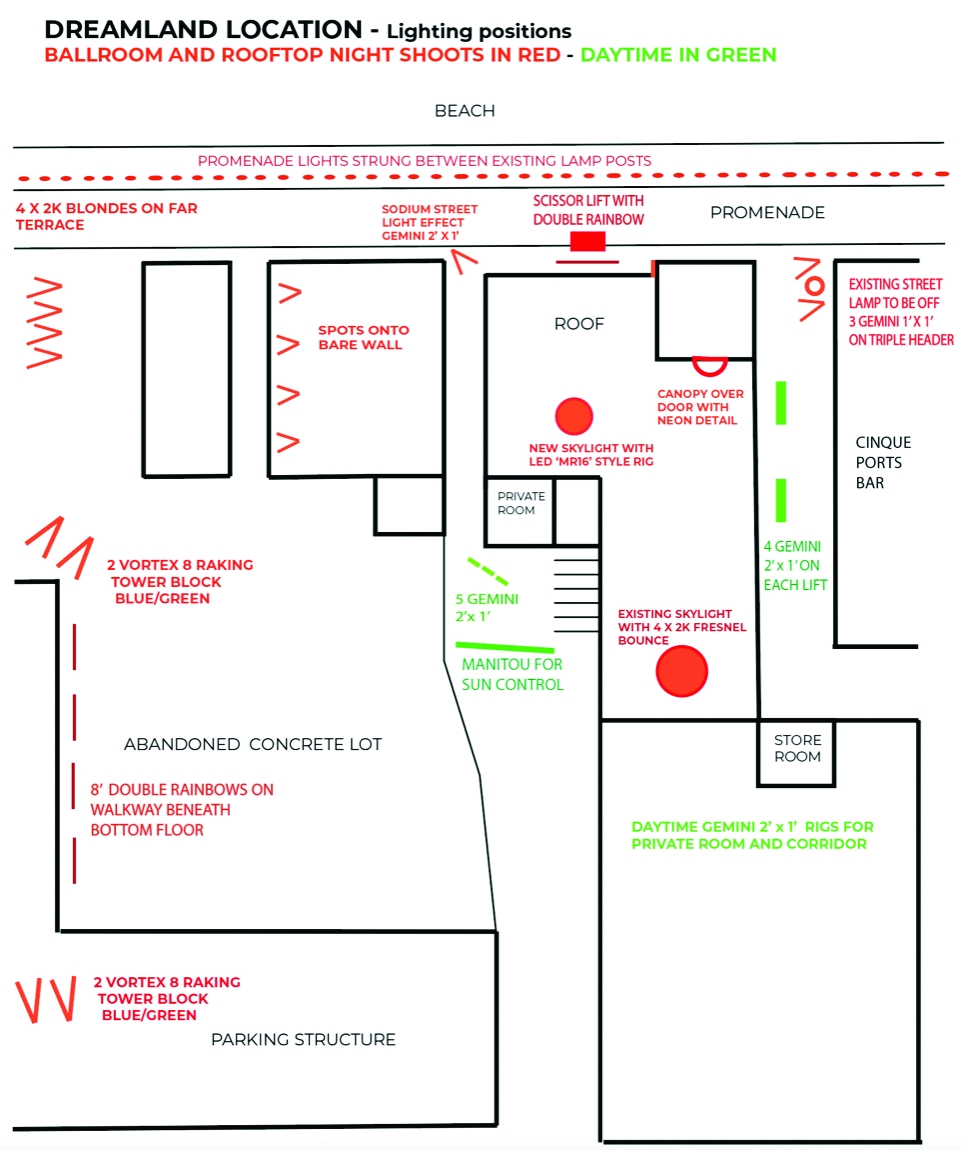

Adapting the Dreamland

Mendes envisioned a particular cinema in Brighton as he wrote the script, but its interior had been transformed into a casino and the facility was no longer feasible as a location. After researching coastal theaters all over England, he settled on the Dreamland in Margate, which doubles for the Empire in the movie. The Art Deco structure dates to 1935, when it was built as part of an amusement park, and the filmmakers determined that its exterior and some interiors would work for the story. Mendes incorporated the cinema’s second-floor ballroom into the script, making it the place where Hilary and Stephen recklessly conduct their trysts.

The main entrance and lobby, however, were just not right. “Luckily, there was an empty lot three doors away,” Deakins says. “[Production designer] Mark Tildesley built our lobby set there, so the view out the doors was exactly the same. We just had to make it feel connected to the rest of the cinema.” The lobby set was two stories tall and included a staircase to the balcony

Mendes wanted the theater’s interior spaces to feel warm and inviting, since the Empire is the characters’ home away from home. “I also wanted it to have a kind of magnificence, the sense that it was standing there defying age and the onslaught of new technologies,” he says. “I wanted to contrast the oranges and browner hues [of the lobby], and the reds and purples of the cinema, with the muted, desaturated bleakness of the English coastline, particularly in winter. And then, within that [palette], I wanted the ballroom to be another world of blues and greens.”

Mendes and Deakins typically arrive at a film’s feel and style through many weeks of intense discussion. For Empire of Light, they referenced the seaside photography of Harry Gruyaert and Martin Parr, whose “use of color is quite bold,” Deakins observes.

Practical Matters

Space for equipment was limited in the Dreamland, and in keeping with Deakins’ preference, practical lights did much of the heavy lifting. “It was a matter of discussing with Mark and set decorator Kamlan Man which lights would work, both photographically and as part of the design of the space,” the cinematographer says.

“I chose to do nearly [all interior lighting] with LEDs,” Deakins continues. “Cost was a reason, but I also wanted total control over the level of the light without the color shifting, as it would with tungsten bulbs.”

LED ribbon provided accent lighting in the walls, and various other LED units were built in elsewhere around the set. Astera tubes were placed in the lobby’s practical chandelier. A rig with at least 10 Litepanels Gemini hard panels, projected through Light Grid diffusion, provided skylight. These were all on individual dimmer systems that were operated via iPhone by lighting-console programmer Galo Dominguez.

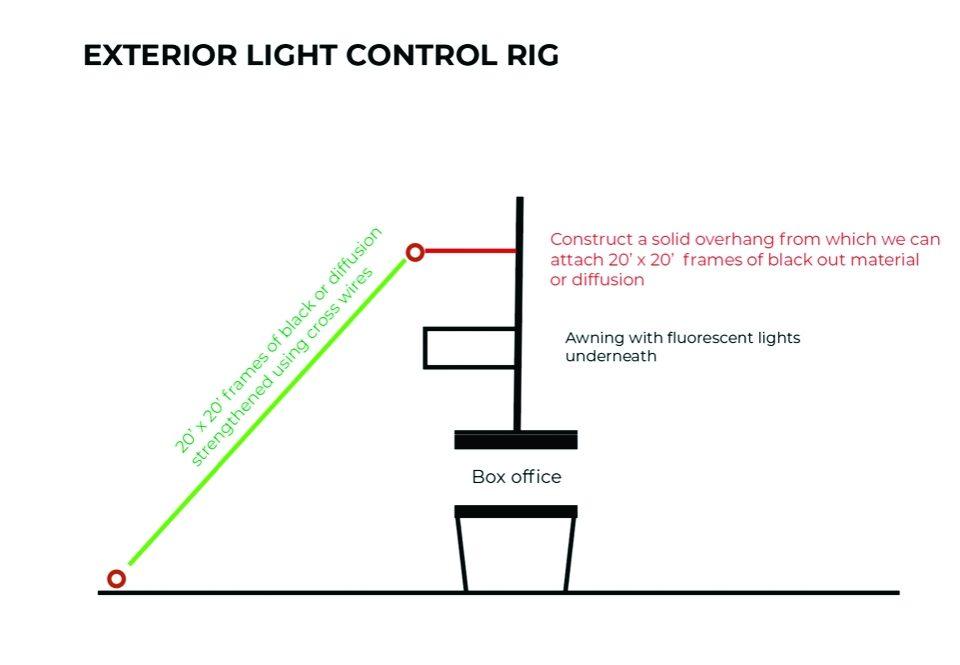

During scenes set in the theater’s lobby, “we were looking out at the exterior street and the ocean beyond it, so we were always trying to maintain a balance with the natural light,” Deakins notes. To control light coming through the lobby’s windows and doors, the crew built an exterior rig from which they could hang 20'x20' frames of black or diffusion.

One of the busiest lobby scenes has guests filing in for the gala premiere of Chariots of Fire. For close-ups, Deakins ganged up four or five Fiilex P3 Color LEDs, whose Fresnel lenses were removed in favor of hexagonal softboxes; these were dimmed down at the edges to produce a soft key. He likens the effect to that of a 1K Pup.

Approaching the Auditorium

The theater auditorium is the setting for an awkward moment during the Chariots of Fire premiere: Hilary, who has not been showing up for work following her breakup with Stephen, unexpectedly walks onstage to join her boss, Mr. Ellis (Colin Firth), and reads a poem to the dumbstruck crowd.

The Dreamland’s auditorium had been transformed into a Bingo hall decades earlier, so Tildesley and his team had to put in a floor, pull the original theater seats out of storage and reinstall them, and erect a projection screen. The riggers, led by gaffer John “Biggles” Higgins and rigging gaffer Terry Robb, had to carefully navigate a circular drop ceiling that contained asbestos.

To augment the many practicals, they built large ring lights lamped with Astera units and suspended them from a motorized hoist: a 12' ring light augmented by three smaller, 8' ring lights — one in the center of the 12-footer, and two others off to each side.

“I’ve built big ring lights for many years, and I used to put household bulbs in them, but I used Asteras here because I wanted to be able to change the color based on the scene we were shooting,” Deakins says. “I wanted a warm feel for the Chariots of Fire premiere, so I kept things at a low level — just a warm glow. It was wonderful that the riggers found a way of mounting those light rigs safely, without disturbing the asbestos.

“I also had a row of Tweenies providing a soft spotlight on Colin and Olivia when they’re standing at the microphone on the stage at the front of the theater’s main auditorium,” he adds. “That was probably the only time I used conventional tungsten lamps.”

Repeat Performance

Deakins shot with an Arri Alexa Mini LF in ArriRaw format at 4.5K resolution, framing in his director’s preferred 2.39:1 aspect ratio. Mendes declares, “We wouldn’t have been able to shoot 1917 the way we did without that camera. It can do almost anything. Once you get used to its capability and its images — how rich and dense the blacks are, and how subtle it is in the middle range — when your cinematographer says, ‘That’s how I’d like to shoot it,’ who am I to argue? I’ve also been astonished by how few technical issues there have been with this equipment across the two movies.”

Deakins used Arri Signature Prime lenses, which he calls “the cleanest lenses I can find, and the fastest. Plus, they’re not heavy, which is a big bonus if you’re shooting on a remote head or handheld — not that there’s much handheld in this film.”

For some scenes tracking Hilary and Stephen walking along the promenade, Deakins used a dolly in conjunction with an Arri Maxima gimbal head. “That’s quite a good gag, as you don’t have to lay track,” he notes. “Sometimes we did lay track, but a lot of the time, key grip Gary Hymns and one of the other grips would just walk with it.”

A Matter of Trust

Deakins notes that because the broad strokes of their movies’ looks are thoroughly discussed during prep, he and Mendes are off doing their own things once production commences — with Deakins at the camera and Mendes by the video playback. There is very little discussion of technicalities. The cinematographer likens this approach to working with the Coen brothers, his frequent collaborators since Barton Fink (1991). “They might say, ‘Maybe you could go a little wider,’ or that sort of thing, but I’ve never heard more than one or two comments about lighting. The directors I’ve worked with have basically left the lighting up to me. We discuss the actors’ blocking, I’ll set up the shot, and then they might say, ‘We want the light a bit lower,’ but not often.

“There’s not much of that intimate exchange with the director by the camera anymore — that’s changed a lot,” Deakins adds. “That’s why I still like operating the camera: I’m there with the actors.”

Mendes says he seldom discusses lighting specifics with Deakins “because I trust his instincts. I’ll just give him my take on the scene and the feel I want for the place, such as ‘warm and inviting’ or ‘cold and forbidding.’”

On Empire of Light, much of the discussion in prep revolved around how Hilary would be framed. Mendes notes, “That’s the spine of the film: the way she is pitched against the larger world, alone in large spaces, or held behind glass or within the cube of the concessions stand — in a private world, detached from people. Stephen breaks through that wall, and we watch her exhilarated rise and then her descent into darkness. We talked a lot about the relationship between camera and central character, and everything else fell into place around that. We’re trying to give you the feeling of what it is to descend into that sort of hell.”

Deakins earned ASC and Academy Award nominations for his work in this project. This marks the cinematographers’ 16th Oscar nomination. He now has the second most nominations in cinematography, and previously won for Blade Runner 2049 and 1917. He only behind the 18 nominations each for ASC members Leon Shamroy and Charles B. Lang Jr.

2.39:1

Camera | Arri Alexa Mini LF

Lenses | Arri Signature Prime