Film Forward

Users and proponents discuss the foundational technology that inspired an art form and continues to deliver exemplary images. (Part 1 in a series.)

The continuing use of film as a tool in the creation of motion pictures will not be determined by objective technical data, subsidies and budgetary gymnastics, or nostalgia for days gone by. Its course will instead be charted by cinematographers determined to use it for a desired onscreen storytelling effect, driven by formative experiences in shooting film and learning what distinctive properties this photochemical tech brings to the table in terms of expressive visual language. The color reproduction, contrast, texture, perceived resolution and exposure latitude of film — among other attributes — are unique to the analog format, in part based upon its very design: a multilayered composite strip of infinitely random light-sensitive particles suspended in a three-dimensional space. Each frame is consistent, yet singular, recording an image that has energy and movement even when the subject may not.

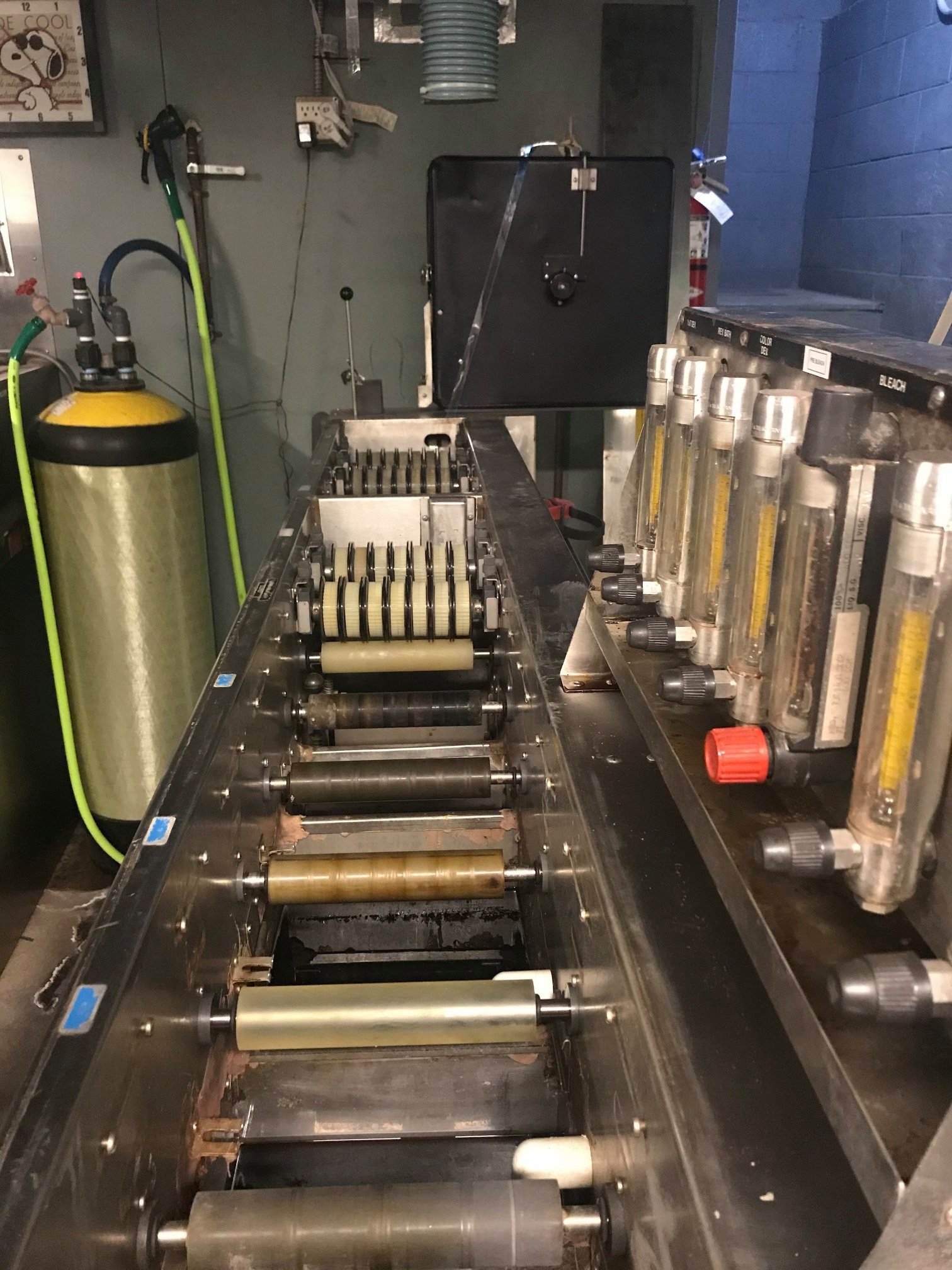

In a series of reports, AC will speak to users across the spectrum, each working to maintain the practice of shooting film by inspiring others to independently investigate its properties. The phrase “use it or lose it” was often repeated in these interviews, in part because technological and artistic expertise in any field is a perishable commodity — especially one as complex as making motion pictures with film, since its users must rely upon the capability of others to make, process and manipulate their negative.

Future installments will include image-making experts working in 35mm and 65mm, as well as manufacturing and lab specialists.

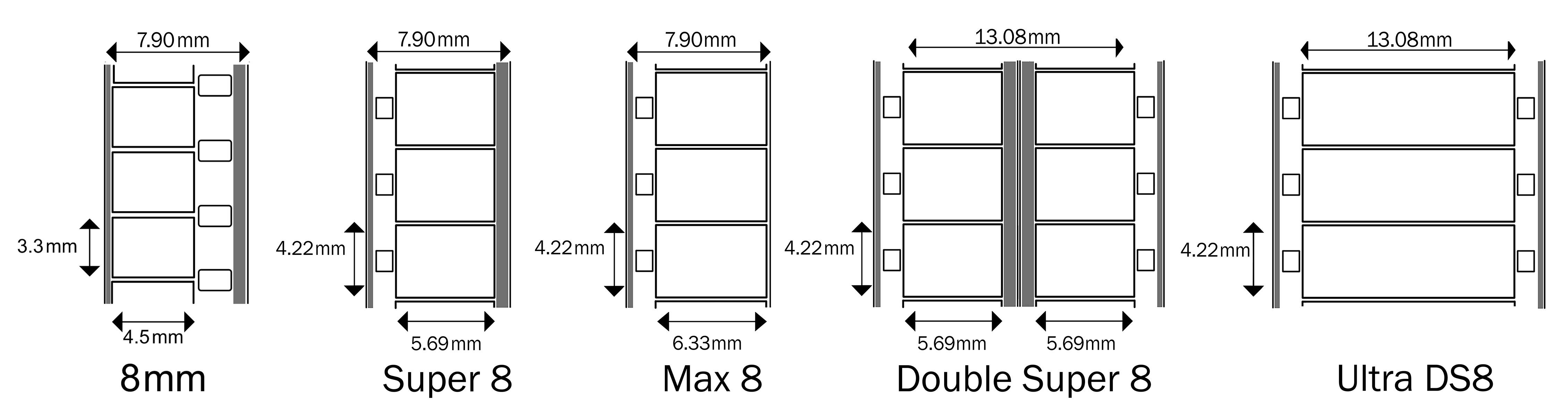

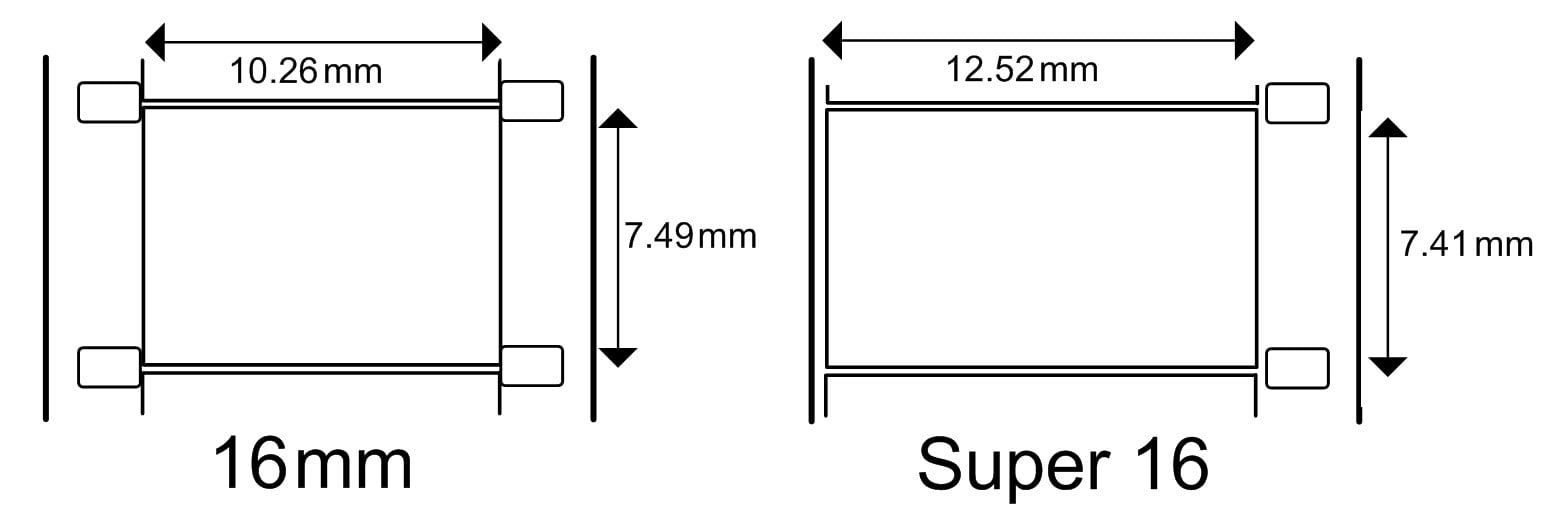

The 8mm and 16mm film formats were each created almost a century ago as compact, cost-effective production options, but are now also embraced for their unique image characteristics.

“If I had a nickel for every time I was told film is going to disappear, I’d be a rich guy,” says Phil Vigeant, an ASC associate member along with his wife and business partner, Rhonda. “Super 8 has been ‘on the brink of extinction’ since we’ve been in business, and that’s 50 years now,” he says. “But it’s thriving.”

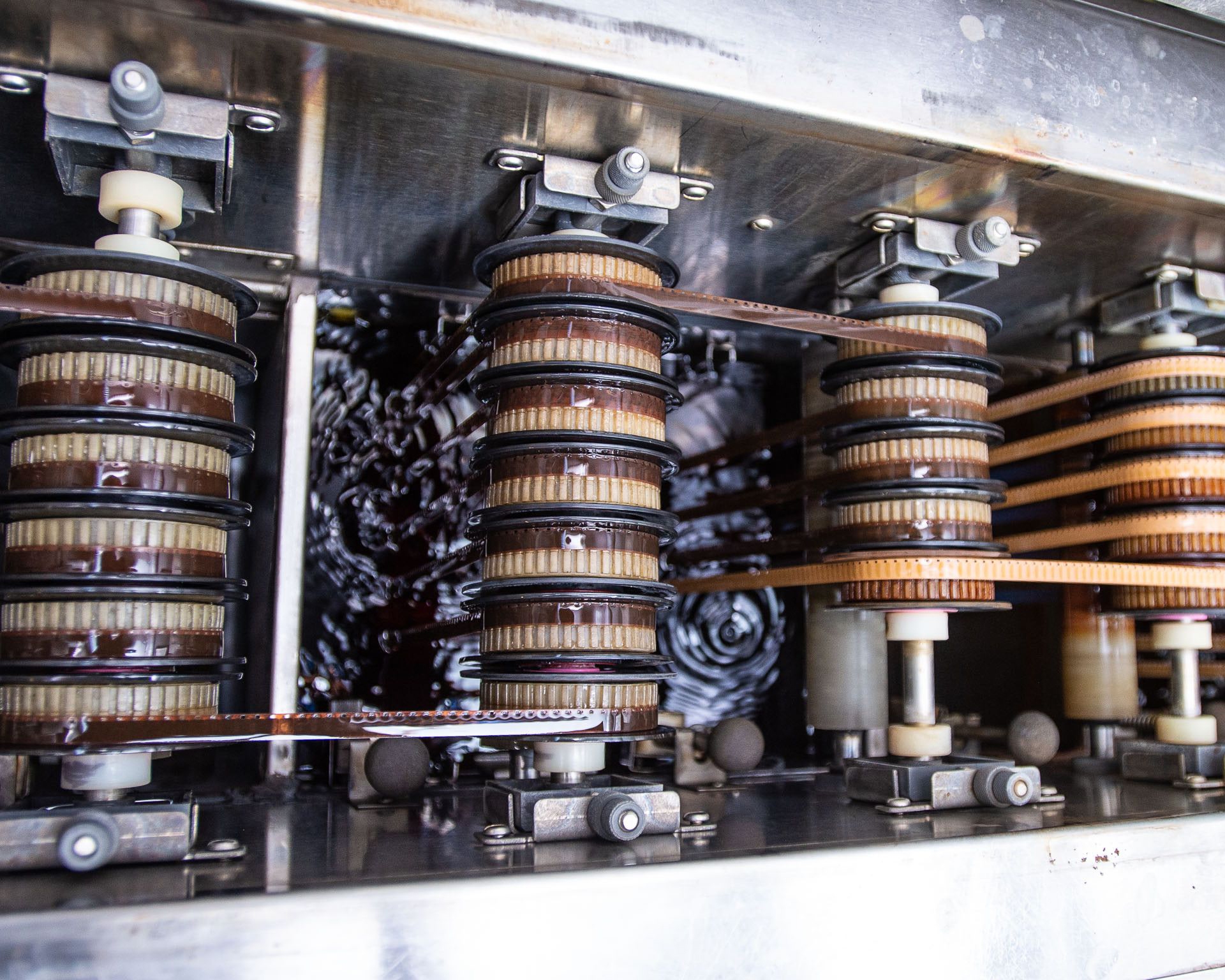

The Vigeants’ company, Pro8mm, pioneered the use of negative film stocks in Super 8 cameras — slitting and perfing 35mm emulsions and loading them into the format’s unique 50' cartridges.

Ironically, digital technology helped make that possible. “The scanning capability we have now — up to 6.5K resolution for 8mm and 16mm — let us see what the stocks are really capable of,” Vigeant says. “In fact, 16mm almost looks too good, so if someone is looking for a certain effect, they may now use Super 8 instead. And when people see the results, they look for other ways to apply it to that next project. So while shooting 8mm was for a long time more about cost savings — the cameras and stocks are cheaper than any other film format — it’s now about the image you can create.”

Presentation is also a factor. “The smaller the screen, the less perceptible image resolution becomes,” Vigeant says. “Shooting 35mm or 16mm may not be necessary. A growing number of our users are shooting for online marketing and Instagram advertising, which will most likely be seen on a smartphone. That proportionality works for Super 8, while it’s also delivering the attributes of film.”

Expectations for small-format filmmaking have also changed. “Super 8 came into its own,” Vigeant says. “For years, we supported users who were struggling to emulate the look of 16mm or 35mm — to hide the fact that they were shooting Super 8. And that was a frustrating battle that just distracted them from focusing on the real challenge of telling their story or creating the mood they were after. Now, there’s an acceptance of what the format does really well, like amplifying grain structure to make the image more impressionistic.”

Digital also drove down the cost of shooting film by making cameras more affordable. “High-quality 8mm and 16mm cameras that once cost thousands can be found for $100 to $300,” Vigeant says. “The price of entry has been dramatically reduced, and there are hundreds of thousands of 8mm and 16mm cameras out there that can still be used with the most modern film stocks to create great images.”

James Chressanthis, ASC, GSC recently directed and shot the music video “Quiet Nights” for recording artist Zoe Scott using a combination of Super 8 and Double Super 8 film and digital formats. (Double Super 8 is a format that utilizes 16mm film, but only exposes half of the frame. Once the end of the roll is reached, the film is removed, flipped, reloaded, and exposed on the second half. Then, in the lab, it is slit into two strips of Super 8mm film.) “The raw simplicity of our footage really knocked people out,” he says. “People are so used to seeing images that are, in a way, too clean and glossy, that they are drawn in by something more textured and personal.”

The footage was processed and then scanned at Pro8mm at 4K and intercut with the digital material. “When we were going through the first throes of the film-to-digital transition more than 15 years ago, one thing I said was that the last motion pictures shot on film would be done on Super 8 and 16mm,” he says. “I was always a big advocate of the digital intermediate — the control and color tools — and believed that Super 16 would be the ideal formal for digital post and distribution. What Ed Lachman [ASC] did on Carol was extraordinary, earning Academy and ASC nominations. And what Matthew Libatique [ASC] did on Black Swan [AC Dec. ’10; also earning Academy and ASC nominations] was also fantastic. Both perfectly paired the organic quality of Super 16 film with the DI.”

For the “Quiet Nights” shoot, Chressanthis borrowed a Bolex Double S8 from Pro8mm and brought along his own “Rhonda Cam,” a Canon 310XL camera modified by Pro8mm. “I’ve been shooting Super 8 since the 1980s,” he notes, “so I have a long history with Phil [Vigeant]. And there’s something so informal about the cameras, in part because of their size — your subject isn’t intimidated. That allows for a relaxed atmosphere, which is exactly what we wanted for Zoe Scott’s performance. It’s unconscious, but it’s there, and it can deeply affect your final result.” Because Chressanthis was shooting at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic in August of 2020, this was a priority.

The only Double Super 8 stock available at the time was Pro8mm’s 50D negative (manufactured from Eastman Kodak Vision3 5203). A “fine-grained and contrasty” stock, Chressanthis says, “it’s great for shooting certain subjects in bright daylight — like cars out in the desert — but I ended up using filtration to bring the image down a bit and reduce the contrast to create a different feeling that was more in line with our sensual, bossa-nova song. I would have preferred the [Vision3] 250D, which I think is the best stock going.”

“Every film format has a psychological effect on the viewer,” says Michael Goi, ASC, ISC about using Super 8 and 16mm during his 52-episode tenure as director of photography on the FX horror series American Horror Story, which was principally shot on 35mm film. “They each have their own visual qualities, which tie together with the viewers’ individual experiences and [their] history of watching images.

For our discussion, Goi supplied a brief clip from his work on “The Origins of Monstrosity” — Episode 6 of AHS’ second season. Shot on Super 8 negative, the scene depicts a 1960s pool party in which a character is humiliated by a cruel practical joke. “The scene wasn’t scripted to be shot on Super 8, but it was a flashback and I wanted it to have the feeling of an unpleasant memory. The scene is brief, so the effect had to work in an immediate way, playing off everybody’s experience with home movies.

“That creative approach was the reason why I frequently used different film stocks and formats on the show — to visually express the story through the use of a particular medium in addition to the framing, lighting, and everything else that goes into a shot or scene.

episode “The Origins of Monstrosity,” shot on Super 8 by Michael Goi, ASC, ISC.

“As an opposite example, I shot a pilot where it was scripted that a flashback scene should look like a home movie, so I thought, ‘Perfect, we’ll shoot Super 8.’ But the producers wanted to shoot in high-def and treat it in post to look like Super 8. Well, we shot it and then they spent three days playing around with the image to make it look organic, as Super 8 does. So they increased the grain, then added sprocket holes, and, in the end, it just looked pretty...fake. And it would have been so easy to do if we’d just shot it correctly, on Super 8. It would’ve looked exactly how they wanted.

“These kinds of situations come from the fear of not having options. It’s the same thing that drives the request that everything digital be shot in raw format, without any color correction baked in. That makes it easier to be played with later.”

Goi notes, however, that cinematographers working in television rarely have the time to participate in those timing sessions, meaning that shooting film is also one of the few ways to help maintain the show’s visual integrity. “I got a lot of compliments on my work in American Horror Story, and I was very proud that I was able to take the images from my head and get them on the screen using primarily in-camera techniques, with very little done in post. If I wanted the image super-saturated, with deep, rich blacks, I’d use color-reversal film. If I wanted everything desaturated, with pastel tones, I’d pull the processing on a particular color negative by two stops. If I wanted black-and-white, I shot black-and-white film. It was easy and immediate, and that helped us get our episodes done on time. But that approach requires the production to be confident in the cinematographer and the vision everyone has agreed upon in prep.”

Says Edward Lachman, ASC, “Our control of the image is dictated by the technology that we’re given and choose to use.”

The cinematographer earned Emmy and ASC nominations for his work on the HBO miniseries Mildred Pierce (AC April ’11), and Academy and ASC nominations for the theatrical-release drama Carol (AC Dec. ’15), both shot on Super 16 and directed by his longtime collaborator Todd Haynes. “Our experience on Mildred Pierce informed our approach to Carol in that we wanted to re-create the look of film in the 1930s and ’40s, and the work of female photojournalists and artists of that time, who were often shooting with Ektachrome [reversal] film. We wanted the feeling of someone looking at their past by paging through a photo album. So as we studied these Ektachrome photos, we thought about how we could see their world the same way they were documenting it in their work. That led us to shoot on Super 16 because of the enhanced grain structure, as well as the distinctive color separation that film would give us as it’s recorded in different layers of the emulsion instead of on a completely flat sensor surface.”

Lachman is careful to note, however, that the digital intermediate process, outputting directly to a DCP for digital distribution, reduced the impact on shooting Super 16; for true film distribution, Carol would have previously required a 35mm interpositive to be made from the 16mm camera negative, from which a 35mm negative would be struck. Those two additional optical generations may have exaggerated the grain structure and contrast beyond the filmmakers’ intention. “The DI allowed us to preserve the results of our in-camera shaping of the image,” Lachman says, “but originating on film was essential to the process.”

Projecting a portion of Mildred Pierce at the Venice Film Festival confirmed the benefits. “That project was made for television, so Todd and I were both surprised by how well it held up on a very big screen. That experience helped us decide that Super 16 was right for Carol.” With a laugh, he adds, “We weren’t trying to be hip.”

Elaborating on the dynamics of film, Lachman says, “It has an almost anthropomorphic quality, because the image is ‘alive.’ Silver-halide crystals are microscopic and invisible, but their completely random, infinite variation between frames creates a ‘breathing,’ an energy that’s perceptible, even subconsciously, to the audience. Much of film language works on that level, and controlling all of those visual cues is what being a cinematographer is really about. In Carol, that grain structure is something living on the surface of the characters’ emotions.” He says it felt appropriate since the secretive romance depicted in the story finds the two female leads “hiding within their own lives, concealing themselves. Their desire is hidden from view, and the grain contributed to that feeling. Some stories need that illusion, just as some paintings are affected by the texture of their brushstroke — pointillism, Impressionism, German Expressionism and even Modernism. I want to use that as well.”

Danny Plotnick, director of film studies at the University of San Francisco, has worked in Super 8 since the 1980s, when he shot his no-budget underground classic short Skate Witches. “Two of the biggest advantages of Super 8 were always its mobility and low price of admission,” he says. “That changed in the 1990s as compact video systems became better and cheaper, so I went away from using analog for a time. But then I taught a 16mm production class at USF in 2013. I questioned why we were teaching it, as it’s a small program and we don’t have a lot of resources, but that class made me rethink everything. These kids grew up with digital, so film is something palpably different — a whole new color in their palette. The grain, the image detail, the contrast — it’s all different from what their eye is used to, and they were very responsive to that. But since we were using reversal stocks — so we could project dailies — there is an unforgiving quality to the work. What you see in the viewfinder is not what you necessarily get on the screen, [and this] requires a deeper understanding of lighting and exposure; it’s a far more nuanced relationship with the image-making process. Many thought the class greatly improved their digital cinematography, as the attention to detail and understanding of the camera transitioned over to that.”

Plotnick recently authored the book Super 8: An Illustrated History — a loving ode to the format, which notes that such filmmakers as Robert Zemeckis, Richard Linklater, Jim Jarmusch, Todd Haynes, Sam Raimi and Wes Anderson all gained experience while using Super 8 to make short films early in their careers. “Being successful in shooting film requires knowledge, planning and intentionality, so it’s a great training ground for filmmakers who want to polish their decision-making process,” he says.

Plotnick adds, however, that digital is a useful educational tool for those interested in shooting film: “You can spend hours experimenting and creating images essentially for free. We could never do that with film because of the cost. As a result, these kids have a better-developed visual style than we ever could at that age. So when they do try film, they’re way ahead even at the beginning. And they have more success early on, which is encouraging.”

Youthful fascination with analog technology is another element in the equation, he says: “I have students who collect LPs, Polaroid cameras, VHS tapes and music on cassettes — film is part of that scene as well.” But their interest also comes with misconceptions: “They know Christopher Nolan says shooting film is the way to go, but I’m not even [sure if] some of them even understood at first that film is a photochemical process — that the footage has to be processed in a lab, and that they would have to wait to see the image. They also embrace light leaks, scratches and dirt as ‘good’ — as part of a visual language — while traditional filmmakers would see those mistakes as disasters. While I always tried to avoid those things, to make my image look professional and more like 16mm, they believe defects make it look ‘real.’”

While some film proponents are accused of simply being nostalgic, Plotnick’s students have no horse in that race: “They just want to try something new, even if it’s just new to them. The images they routinely see have a very consistent look to their eyes, and film — especially in a format like Super 8 or 16mm, which amplifies the characteristics of film — looks different to them. It’s not better or worse, but different. Will they keep shooting it? That remains to be seen.”

For Liza Voloshin, the “defects” are part of what drew her to shooting film. The director and visual artist made waves last year by photographing Katy Perry’s music video “Daisies” on Super 8 negative — not only to create an impressionistic effect, but also to establish a unique sense of intimacy with her subject. The clip, with 26.5 million views on YouTube, features the singer, who is visibly pregnant, performing in a variety of natural settings, depicted in a floating, dreamlike, impressionistic style that makes the most of the format’s mobility and the image’s grain structure.

“I got into shooting film after I saw that Pro8mm was selling reconditioned Canon 310XLs — what they call the Rhonda Cam — which is so compact that I could just imagine walking around New York City and shooting with it,” says Voloshin, who now considers her Pro8mm-modified Beaulieu 4008 camera a prized possession. “I started incorporating film into my projects, and that very first footage was used for ‘The Age of Misinformation,’ an installation I did for the Whitney Museum [and their Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905- 2016 exhibit in 2016]. The images felt immediate and tactile, and not like you could blow on them and they would disappear, like so much of our digital world does.”

Super 8 was a perfect medium for “The Age of Misinformation” as “it was a look at how technology changes our perception of the world,” says Voloshin. “Using 8mm film seemed an honest thing to do, [since] the process is all about dishonesty as you control the perception through framing and angles and editing, and film itself is a perception of reality rather than just a recording.

The Canon 310XLs made Voloshin feel “one with the camera, with the least amount of visible technology between me and the image I’m capturing,” a notion that came into play on the “Daisies” shoot with Perry at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. “I knew I couldn’t have a crew of any kind, or equipment, that it would just be us. Katy really wanted to shoot on film, as that was her vision, so we literally went out with my two cameras and a backpack full of Super 8 film, climbed a mountain and shot it. That giant grain and gentle pixilation around the subject is just beautiful; everybody looks beautiful in 8mm, and I can feel that the image has been created by a human hand. Even though it’s been digitized and is seen on a screen, that tactile element is still there. That’s very important and comforting in today’s world, especially during a pandemic. You feel it even if you don’t understand it.

“The experience made me reconsider how I approach image-making — to think about simplifying the behind-the-scenes process, making it clean and uncluttered, and focusing on creating something as beautiful as possible without getting lost in technology. Every time you add a piece of equipment to a space, you add an energy, and that affects the process. So if you can strip away everything possible, even if it’s not on camera, you get to a cleaner, more authentic result.”

She laughs, thinking of the cinematographers she has worked with who are shocked that her preferred lighting instrument is a humble flashlight: “Shooting with the 500T stock [manufactured by Pro8mm from Eastman Kodak Vision3 5219], it’s perfect.”

To Vigeant, it’s clear that film’s future is dependent upon the next generation having the opportunity to at least try shooting it. “That’s one reason why we worked on Kodak for so long to reintroduce double-perf 16mm film, which they had not sold in decades,” he says.

“We finally got it out this year. Just because it’s available again, thousands and thousands of film cameras that were just doorstops can now be put back to work in the hands of filmmakers who really want to learn, but just need a chance to do so.”

Double-perf 16mm was popularized in the 1920s as a compact alternative to 35mm, and later offered in a single-perf version to allow space for a soundtrack. This single-perf format was later enhanced as “Super 16” in the 1960s by Swedish cinematographer Rune Ericson, FSF, who reclaimed the soundtrack space and enlarged the camera’s gate and exposed imaging area to maximize quality.

Color and black-and-white negative and reversal stocks were standard, offered by Eastman, Fujifilm, Ansco, Agfa and others. Cameras were produced by companies including Kodak, Bell & Howell, Mitchell, Aaton, Éclair, Cinema Products, Arri, Bolex, Beaulieu, Canon and Panavision.

After Kodak discontinued double-perf 16mm film decades ago, many high-quality cameras were rendered obsolete. Pro8mm recently convinced the company to reissue the stock, making those cameras viable once more. Alternative sources for the stock include the Film Photography Project.

Eastman Kodak introduced the 8mm format during the 1930s as an inexpensive alternative to 16mm. In the 1960s, Eastman upgraded 8mm to “Super 8,” employing an enlarged gate to enhance image quality, as well as a plastic film cartridge to simplify operation — and the motion-picture camera became a mass-market consumer product. Cameras were offered by many companies, including Kodak, Beaulieu, Bell & Howell, Canon, Zeiss, Nikon, Braun, Elmo and Leica.

Projection-ready color and black-and-white reversal stocks, primarily from Eastman, Ansco and Agfa, were the norm into the 1990s, when Pro8mm pioneered remanufacturing 35mm emulsions into Super 8. Eastman Kodak and Spectra Film & Video, among other companies, followed suit.

In 2018, Kodak reintroduced Ektachrome reversal film for Super 8 and 16mm.

Partnered with Danish company Logmar Camera Solutions, Kodak recently explored the market for a new Super 8 camera that combines pin-registered film imaging with digital audio and operation. On Pro8mm’s part, the company has long been enhancing existing cameras with enlarged gates — offering Max8 in 2005 (featuring a wider aperture that can be employed with anamorphic lenses) and Ultra-DS8 in 2020 (offering a panoramic image by modifying Double Super 8 units).

The 8mm format was also the basis of the alternative Fujifilm Single-8 and Polaroid Polavision systems. — David E. Williams

The next part of this Film Forward article series will appear in a forthcoming issue of AC.