When Nature Enters: Filming Earth Mama

Cinematographer Jody Lee Lipes, ASC gets the right look with 16mm for this moving social drama

In Earth Mama, written and directed by Savanah Leaf and photographed by Emmy-nominated cinematographer Jody Lee Lipes, ASC, Oakland rapper Tia Nomore plays Gia, a young, pregnant single mother of two living in the Bay Area and struggling with the decision to keep her unborn child or give it up for adoption. The film is thematically based on Leaf’s 2020 documentary short, The Heart Still Hums (co-directed by Taylor Russell), about five women as they fight for their children through the cycle of homelessness, drug addictions and neglect from their own parents. That same year, Lipes was shooting a commercial in South Africa, when he became aware of Leaf — a commercial director herself — and her work.

“The thing that was really special about the time I had with Savanah was just how much of it was about the story...”

— Jody Lee Lipes, ASC

“I was immediately taken by it,” Lipes recalls in an interview with AC. “I wanted to meet her, and then the pandemic happened, but we ended up having coffee and got along really well. We did a Biden-Harris campaign commercial and a spot for Dick’s Sporting Goods, and soon after that, she mentioned she had a movie that she was trying to make.”

In the film’s press notes, Leaf says that she wanted to work with Lipes because “Jody does such a great job of never imposing himself. You don’t feel his presence as a cinematographer, which I really love about his work. Instead, you feel the characters driving the visual language.”

Lipes was interested in another collaboration with Leaf, but didn’t immediately commit to the project. “A lot of commercial directors have a feature script in their back pocket, but it’s just so hard to get a movie made,” he remarks. “Then one day, my agent contacted me with Earth Mama, and I was really impressed with what I read. It didn’t have a first-time screenwriter feeling to it.”

American Cinematographer: In what way?

Jody Lee Lipes, ASC: It just felt really emotionally mature. It depicted this very specific community in the Bay Area and what life is like for parents with children in the care of protective services in a way I had never seen before. But I came with assumptions that were totally wrong, like, this is such a gritty, real story and Savanah is going to want that same kind of visual sensibility. I thought, Savanah will probably want to shoot all handheld, and it’s going to have this Dardenne Brothers look, which I love when they do it, but would be totally wrong for this movie. When I actually talked to her about it, she told me without being prompted that this was not at all what she wanted to do.

What was her vision?

She wanted a mixture. The 16mm format, the almost amateur lighting style, and the drugstore film development look were rough and gritty, but the coverage, the lens choices, and the camera movement were formal and strong.

[Leaf comments, “I wanted to shoot Gia in a matter-of-fact but heroic way. I really felt that just because she’s broke, we don’t have to shoot her like she's broke.”]

Are there other films you’re aware of that have done that, or that you and Savanah were influenced by in the making of this film?

Visually speaking, the thing that influenced me the most was Savanah’s photography. She took a bunch of 35mm stills when she was location scouting before I started, and had them processed at a drug store. I loved the look of those photos and the way they were printed. Usually I’m really boring, in that I pretty much only use film references, not photography references. That long lateral tracking shot at the sideshow in Earth Mama was taken from Michael Haneke’s Code Unknown, and Ed Lachman [ASC]’s 16mm work was a huge influence. Narratively speaking, I think [Ken Loach’s] Ladybird, Ladybird is the closest movie to ours, in that it explores the complexity of being a parent who really loves their children and wants to be with them, but doesn’t always make the best choices. They’re both about this complex character who's not right and not wrong, but somewhere in the middle, which makes them relatable.

What role does the cinematographer play in bringing these characters to life?

The thing that was really special about the time I had with Savanah was just how much of it was about the story and just going over the words. We spent a lot of time talking about every single scene, trying to find what was essential and what wasn't. It was part of the writing process for Savanah. If we found out that a scene was too complex visually, in that it required too many shots, Savanah would rewrite and simplify the story.

I read in your Filmmaker Magazine interview that you and Savanah shotlisted almost the whole film prior to shooting. Was that before or after you secured your locations?

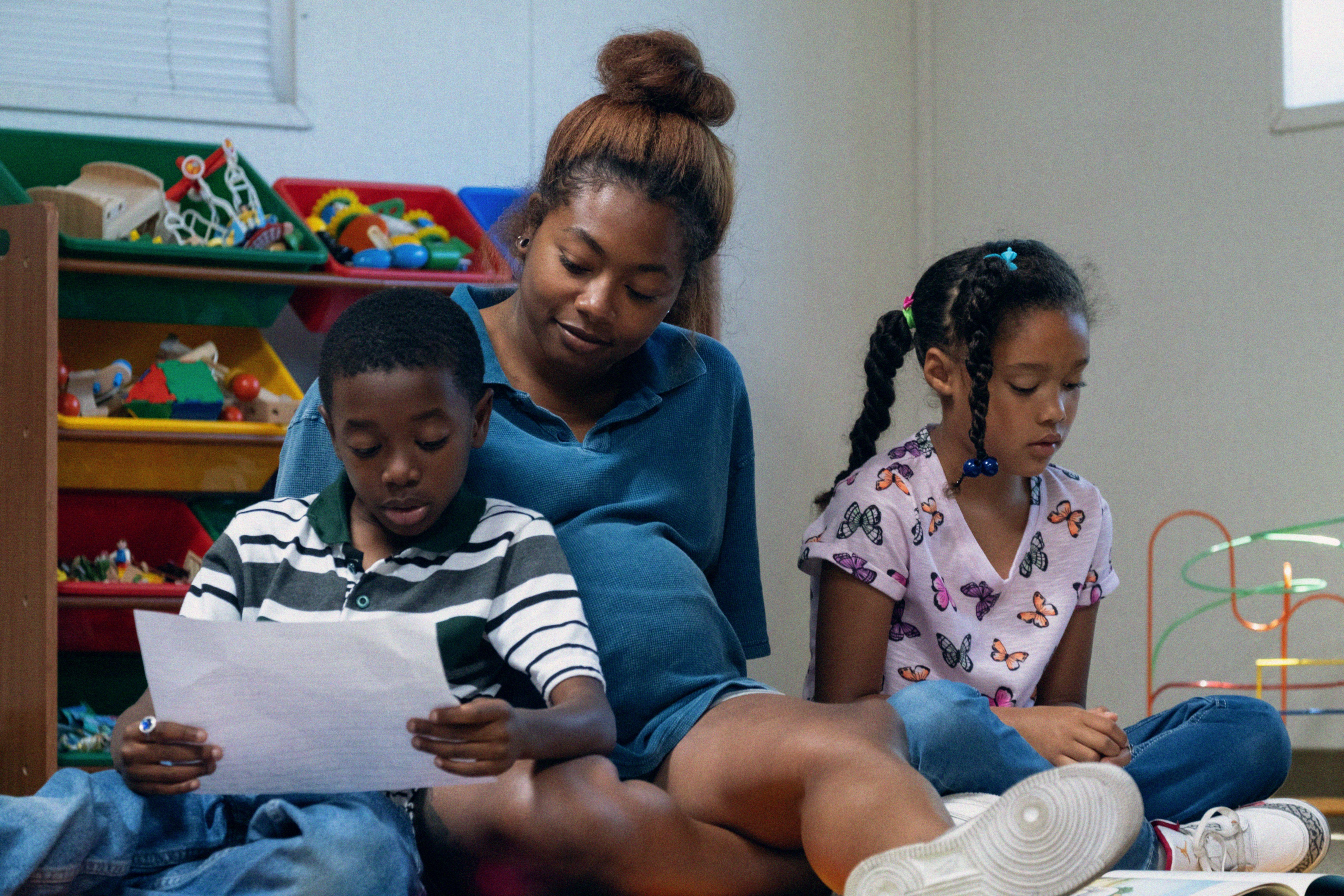

It’s back and forth. Take for example, the first scene where Gia visits her children. Savanah had this specific idea about the room, and where the windows and doors were, and the relationship to a parking lot outside. We were hoping to find a location that matched her vision exactly, so we created a oner that would work in this imagined space. Then we found a room that had the exact layout and relationship to the parking lot that she wanted. In other situations, we didn’t find the exact location and had to change the blocking. But we really did go through the script in extreme detail, many times over, and had a pretty thorough shot list for 90-95% of the scenes in the film.

The shot you mentioned with Gia and her two children, who are in protective custody, I thought was really clever in the way that it was photographed: the way the camera tracks from person to person, using depth of field to isolate characters, and blocking to create new compositions. How do you build a shot like that?

It’s just a feeling, like, knowing what’s the right thing to do. Part of it is creating the sensation that there’s this observer looming in the background, like a clock or an unwelcome presence that’s just over your shoulder, because ultimately, Gia’s going to watch her children drive away with a stranger, and there’s nothing she can do about it. For Savanah, there was also this through line of nature and how it’s absent from Gia’s world, and the magical realism of nature coming into her world, which sets up this important relationship between the room, and the parking lot and the tree outside of the room. All of those things together, with the actors’ performances on the day, ended up making the shot.

You talked about trying to find what was essential to the story, and I was struck by the use of certain color motifs in the lighting, production design, and costumes: soft pastels, contrasting colors, and earth tones. How is color essential to the story?

I’m really bad at paying attention to color. It’s one of these things that I just totally ignore, I don’t even want to know what the production designer and the director are doing with it. If it’s there, it’s there. Savanah had been frustrated by the way black people’s skin is often graded or represented in film, so the simple way of expressing what she wanted was warm, black skin. What’s the byproduct of that? How does that affect other colors? I think that’s part of what you’re seeing with the earth tones in certain scenes. Juliana [Barreto Barreto] the production designer and Savanah would be able to answer that question better, because I kind of ignore all that, even though I shouldn’t.

[Leaf says Barreto “did a really great job of creating a color palette that’s specific to the early 2000s. In general, I wanted a lot of color to Gia’s world. Color is so vital to her dreams and her ideas of escape.”]

Maybe we should unpack that a little bit, because everyone sees the world in a different way. When you look through the camera, there’s something in your taste and experience that tells you the colors are right. You might not have chosen them yourself or thought deeply about it, but you know what works when you see it.

I think that people tend to assume filmmaking is something that you’re controlling, when sometimes it’s kind of the opposite. There are things that I don’t notice that are incredibly obvious to most other people, but because I’m not considering them, the choices I make may seem different, or unique. A lot of me ignoring color also comes out of all the conversations on so many productions where the idea was to only see this color in these scenes, or that color in those scenes, and then it just never happens because people give up, it’s not thought through enough, or they can’t control it. With the project I’m working on right now, the director and the production designer are conscious of color in a way I’ve never experienced before, to a level I’ve never experienced before, and I really do see it and feel it for the first time.

You must’ve had conversations before with directors or production designers or people in the art department after looking through the lens and seeing a pattern or color doing something you don’t want it to.

Yes, those things I’ll definitely address. As opposed to establishing a color motif though, I am generally more focused on shotmaking, shapes, depth, and light quality.

I noticed a lot of tight framing, and shots on the long end of the lens. The first driving scene was filmed extremely close up. What’s behind that?

It isn’t a conscious thing. In that particular scene you mentioned, it just felt like those were the right shots. But also, it is a period piece — the early 2000s — so we’re [using long focal lengths and] hiding the environment because we’re a small film and can't control whether the cars on the street are period-appropriate. I generally avoid super-wide lenses anyway, and going super wide-angle is hard to do when you’re using 35mm lenses on a 16mm camera. I often feel distracted by wide lenses, more so than long lenses, and that’s my goal as a DP, to not be distracting.

“Shooting on film, there can be more to worry about — the lighting budget is higher, there could be focus issues, and lab issues, the mag could get flashed — but being forced to shoot digitally when it’s not the correct format for your story is way harder than any of those problems.”

I understand your lenses were ARRI Master Primes, and you shot on Kodak Vision 3 7219 500T, rated ISO 1000. When did you make the decision to shoot on film?

It was pretty early on. When Savanah first brought it up, she was thinking about 35mm, but I suggested 16mm. She was a bit hesitant, but we tested it, and it felt right. I felt it would give the period an immediate aesthetic. The Master Primes were a functional, ease-of use decision. I had spent the last couple projects before this — a movie called The Good Nurse and the first two episodes of Dead Ringers — testing lenses and getting really particular about them, and I didn’t want any of that to be a part of this process. I didn’t want to waste time on technical things. I know Master Primes. I’ve shot commercials with them, movies with them, tv shows with them. And there are a lot of focal lengths in the set, which is really important to me because sometimes three millimeters can make a big difference.

You also had the Angénieux Optimo 24-290mm.

Yeah, which we used a lot.

Did you use it for the oner in the visitation scene?

Yes we did. And you said something before about depth of field; Kali Riley was the first AC on this film, and she is one of the most incredible focus pullers in the world. I never have to worry about focus when she’s with me.

You shot wide open, too. What’s that on a Master Prime, T/1.3?

Wide open sometimes, but mostly T/2, or sometimes T/2.8.

You said there was some hesitancy on Savanah’s behalf when it came to shooting on 16mm. Why was that?

She was mostly concerned that details would be lost in the wide shots. But then we watched Ulrich Seidel’s Import Export and the Paradise series of films he did with Ed Lachman, and she really liked the way they looked, which made her more excited about 16mm.

If it’s an aesthetic you’re after, why was it important to shoot on 16mm film, rather than capture digitally, with a larger sensor, then add the grain in post?

Maybe I’m just a bad DP, but shooting on film was an easy way to make this film look right. Shooting on film, there can be more to worry about — the lighting budget is higher, there could be focus issues, and lab issues, the mag could get flashed — but being forced to shoot digitally when it’s not the correct format for your story is way harder than any of those problems. There are stories that digital is better for, like Miami Vice — that movie is supposed to be a digital-looking movie, and it looks amazing. It’s not impossible to get something visually special with a digital camera, but to me, it’s a much harder process, and it wasn’t right for this movie. So film is something I usually fight for, but it really has to come from the director. In this case, Savanah stood her ground. I think that’s the only way you can do it now, when a director can’t be scared out of committing to their choice.

“When someone like Savanah puts her foot down and insists on choosing her aesthetic as a filmmaker, in this case, celluloid, you can feel it in the finished product. The movie has a voice.”

How strong is the push back from producers or studios when it comes to film, 16mm in particular, which seems to be having something of a stylistic renaissance post-digital cinema revolution?

It’s still very hard. The question is, “Why is it hard?” I’ve noticed since right after Tiny Furniture that the format question is usually portrayed as a financial issue, when I think it can be more of an emotional issue. I can’t tell you how many projects I've been on where we’re told for X, Y, and Z reasons that we can’t shoot film. We solve those problems, and now we’re told it’s something else. After a while, you get the feeling that it’s not really about the money — it’s about fear and control. And those are really hard issues to negotiate. I worked on a studio movie where the director and I really wanted to shoot on film, but the studio kept saying “No,” because they thought it was going to be too expensive. For months in prep we argued that shooting on film was the right thing to do, and, ultimately, one of the producers called me on the phone and said the studio would give us a bigger budget if we shot with a digital camera. After insisting it was a financial issue, they actually gave us more money than it would have cost to shoot on film, so that we would not shoot on film. It’s the kind of argument that takes so much energy and so much time, you have to ask yourself, “Why does this have to be this way?” What's actually at stake here? When someone like Savanah puts her foot down and insists on choosing her aesthetic as a filmmaker, in this case, celluloid, you can feel it in the finished product. The movie has a voice.

Earth Mama was filmed with an ARRI 416 camera and processed at Kodak Atlanta. The grade was performed by Sam Daley at Light Iron, for a 4K 1.66:1 deliverable.