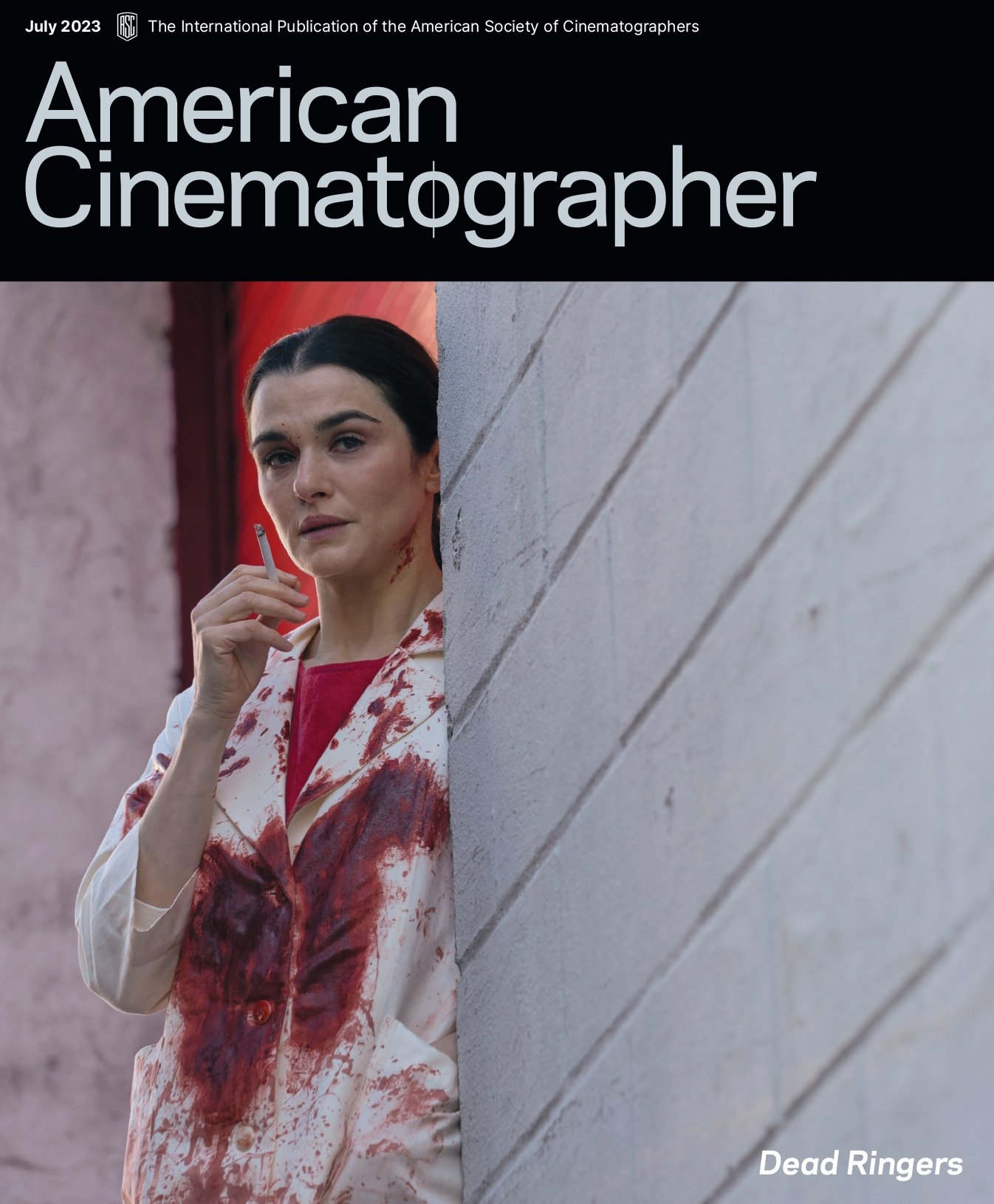

Seeing Double for Dead Ringers

Cinematographers Jody Lee Lipes, ASC and Laura M. Gonçalves help frame Rachel Weisz as obsessive identical twins.

The Amazon Prime Video limited series Dead Ringers, shot by Jody Lee Lipes, ASC and Laura M. Gonçalves, offers a reimagining of the David Cronenberg-directed classic. This time around, actor Rachel Weisz takes on the roles once inhabited by Jeremy Irons: Elliot and Beverly Mantle, a pair of pathologically codependent identical-twin gynecologists who steadily make their way toward psychosis and self-destruction. During prep for an HBO project in 2021, Lipes had dissected the 1988 film — shot by Society member Peter Suschitzky — and what he drew from it “is that it’s not the real world. It’s a stark, slightly tweaked, theatrical world. To me, that was license to work in a way that heightens reality.”

“One of the great things about this show is all of the experimenting we were able to do.”

Collaboration and Spontaneity

Lipes was called to shoot this new version of Dead Ringers by executive producer and director Sean Durkin. In addition to continuing a close collaborative relationship that began in film school — Durkin produced Lipes’ first feature as director of photography, the 2008 drama Afterschool, and Lipes shot Durkin’s directorial debut, the 2011 psychological thriller Martha Marcy May Marlene — the director sought to benefit from the cinematographer’s experience in television, and particularly on the aforementioned HBO production, the 2020 miniseries I Know This Much Is True, which features Mark Ruffalo playing identical twins.

Lipes recalls that project as “incredibly challenging,” shooting on 35mm, with Ruffalo gaining weight for one twin during a six-week hiatus, “then coming back to film the ‘B-side’ of shots and having to match the lighting exactly, up to four months later, on location. The process stuck in my head, and I was able to work with more confidence on Dead Ringers.”

Lipes spent time in prep with Durkin looking at frame captures from many disparate cinematic reference points — everything from the two-hander Persona (shot by Sven Nykvist, ASC, FSF) to the horror classic Suspiria (shot by Luciano Tovoli, ASC, AIC) and the dark-toned Black Swan (shot by Matthew Libatique, ASC, LPS). “I love working with Sean,” Lipes says. “He’s often unsure of what he wants to do, open to input. He wants to talk about it, he wants to figure it out — and then, at a certain point, makes a clear decision. It’s nice when a director can simultaneously share their insecurity, their lack of confidence, and then commit to a strong point of view when they need to.”

Episodes 1 and 2 of Dead Ringers were shot by Lipes and directed by Durkin, the latter of whom co-directed Episode 6 with Lauren Wolkstein. Serving as cinematographer for the remaining four episodes was Laura M. Gonçalves, one of AC’s 2020 Rising Stars of Cinematography (AC March ’20). In addition to her work with Durkin and Wolkstein (Wolkstein also directed Episode 4), Gonçalves collaborated with directors Karena Evans (Episode 3) and Karyn Kusama (Episode 5).

Gonçalves’ initial discussions with Durkin and showrunner Alice Birch, she recalls, were centered around “the theme and tone of the show — and then they connected me with Jody, who was open and generous, and brought me into the fold right away. His attitude was, ‘I’m going to tell you what I’m thinking — tell me what you’re thinking.’”

Double Takes

Capturing Weisz as both of the twins in the same shot would call for a similar motion-control approach as used on the 1988 film. Given that Lipes had already worked with a team well-schooled in actor-twinning techniques, the cinematographer wisely introduced Durkin to I Know This Much Is True visual-effects supervisor and producer Eric Pascarelli, who came on board along with that series’ A-camera operator Sam Ellison, key grip Johnny Erbes-Chan, and 1st AC Zach Rubin (who was a day player and B-camera 1st AC on I Know This Much Is True). “So, there was a familiarity on the crew — people who understood the whole process and what goes into it,” Lipes says.

The crew employed a Sony Venice camera on an Aerohead repeatable remote-head system, which was run by motion-control operator Don Canfield on a Kuper Control computer. They shot Weisz as one twin, as she played opposite acting double Kitty Hawthorne as the other. They would choose a good take, and then for shooting the B-side — with the actors switching roles — “play back” the moves from that take, which the operator had made with the Aerohead’s pan-tilt-roll wheels, 1st AC Zach Rubin’s focus pulls, and occasional zooms by Lipes and Gonçalves. (Justin Foster served as A-camera operator for Gonçalves.)

As a general rule, Weisz’ two performances were then composited in post, though Pascarelli adds that sometimes AI deepfake technology was applied in visual effects, whereby Hawthorne’s performance as one of the twins was kept and her facial features were replaced by Weisz’s. This was used, for example, on a day when Weisz had to leave early, but was otherwise mostly avoided to maintain the integrity of her performance.

The crew’s biggest challenge was maintaining lighting continuity between the A-side and B-side. Particularly tricky was an early-morning scene in Episode 1, in which the twins leave the Manhattan apartment they share and walk to work. “It was early, so it was a bit dark and pre-direct light,” Lipes recalls. “We shot for more than half a day — so, at a certain point, the sun would be coming down the avenue and bouncing off windows and all around, and hitting the actors. We had to plan how to keep the direct sun out of the B-side.”

Controlling the daylight fell to key grip Erbes-Chan, who explains, “Side A was shot in the shade of the building in the morning. For side B, when the sun came around in the afternoon, we blocked it with Ultra Bounce, Magic Cloth and nets. It was difficult, as we were on Park Avenue and couldn’t use any machinery.” And without the use of condors or construction cranes, the rigging needed to be supported with stands. Lipes adds that blocking with Ultra Bounce has the benefit of having “white on one side, thereby creating a passive bounce, as well as blocking the direct sun.”

Gonçalves points to moments when the twins physically interact as the most demanding, as in a scene in which the sisters are lying in bed together and touch each other’s faces.

“We would commit to the A-side and time it out in rehearsal,” she says. “Rachel would rehearse both sides and Kitty would memorize that, so she would know when she was going to touch Rachel’s face, and then Rachel would later do it, listening to dialogue played back on an earpiece. On the VTR, we would have a split-screen lineup of the B-side we were shooting with the A-side, to make sure the arm was in the right position.”

Demystifying Childbirth

Further amplifying the series’ heightened reality are the production design of Erin Magill and Adam Scher and costume design of Keri Langerman and Mickey Carlton. We first see the Mantles working in a conventional hospital wearing blue scrubs in an environment of muted color, and by Episode 3, they are in their futuristic research center, operating in blood-red robes, as in the Cronenberg film.

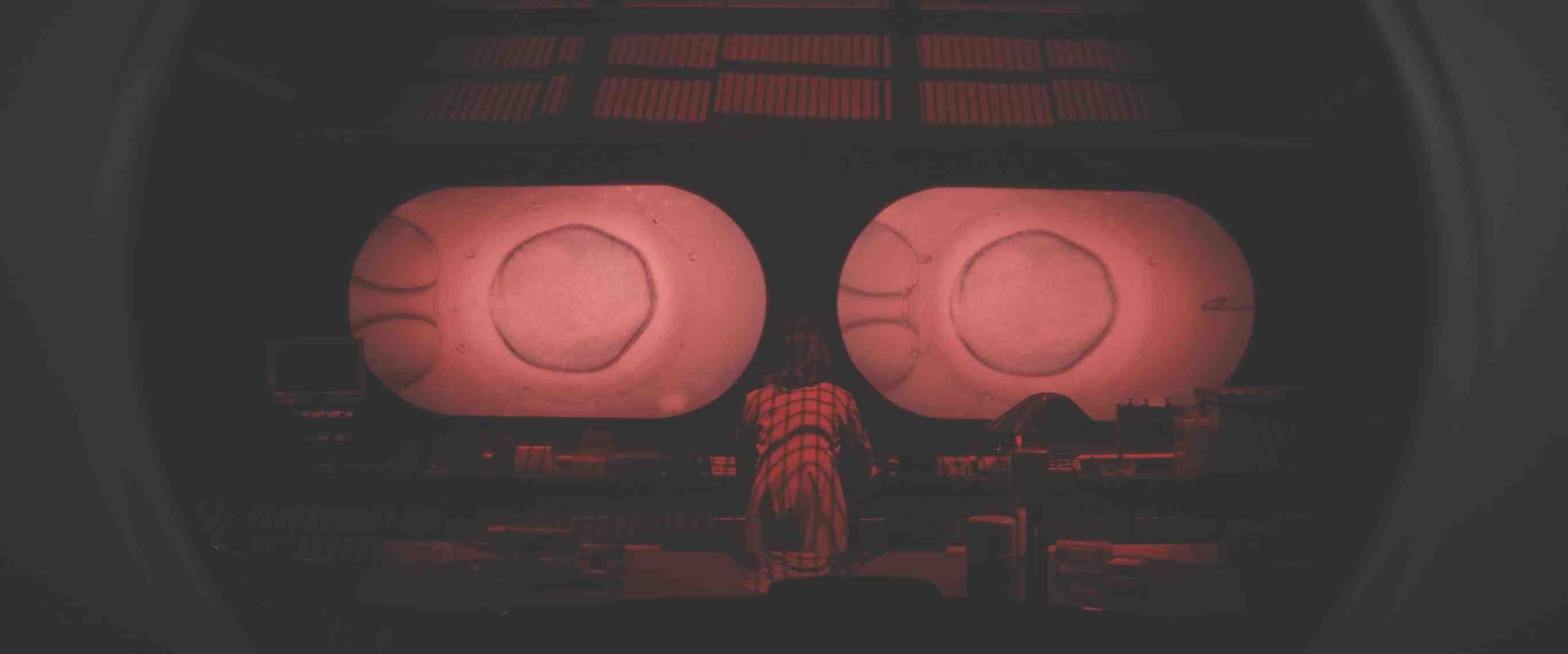

The birthing center combined three different locations. The exterior was based on the Seaglass Carousel in New York’s Battery Park, expanded upon by the visual-effects team; the atrium was filmed in an underground recreation center; and Elliot’s lab area was shot at the TWA Hotel at JFK Airport — a refurbished terminal with an observation room illuminated by circular space-age ceiling lights.

The birthing rooms were staged at Silvercup Studios in Queens, where Gonçalves — whose other series credits include Generation and Fracture — collaborated with Birch, Durkin and Magill on creating a space that furthered the idea of a forward-thinking facility.

“The Mantles’ vision for the space was [about] demystifying childbirth and people being able to watch and interact with loved ones. So, we talked about what that should look like,” Gonçalves says. “We wanted to shoot through windows and obstructions to create layers, and the design team was great — giving me windows where I wanted them and making them the precise dimensions I thought would be best for our lensing and aspect ratio.”

There are many practicals in the center — as well as elsewhere in the series — including some unconventional fixtures, such as an octagonal overhead light in the birthing suite. “Erin and I worked on that,” Gonçalves says. She adds with a laugh, “It’s one of the biggest nods to the original film if you’re a Cronenberg geek.” The octagonal overhead light, Velez notes, consisted of “Astera Titans running on the perimeter soffit — and in the open space in the middle, we pushed through DMG Lumiere Maxis. For a few scenes, we switched out the Maxis for ETC Lustrs, for a harder light. We would use the Lustrs with 26-degree lenses, along with an iris to control the light precisely — like [for a scene shot] on a woman’s belly during a C-section.”

Nightmare Scenarios

Frequently, Dead Ringers calls into question whether certain events are actually happening or are being witnessed through the lens of Elliot’s drug-addled imagination — a feeling conveyed through camera movement and lighting.

At the start of Episode 2, for example, the camera tilts up on Beverly — eyes closed on an examination table — continuing all the way to reveal Elliot, upside down, about to administer a large needle, as the light suddenly turns red. “It feels like a nightmare — or the twins descending into a psychotic episode,” Lipes notes.

Enabling this light-color flexibility were Rosco DMG Lumière LEDs. “We used them primarily on the actors as the light quality and color rendition is incredible,” notes gaffer Jason Velez. “We also used Astera Titan Tubes in built-in soffits to light the perimeter walls.”

Workhorses throughout the production, the DMGs were used in the Mantle’s apartment, built on-stage at Silvercup. At the end of Episode 1, Elliot returns home at night and realizes Beverly has Genevieve (Britne Oldford) — a TV actor Beverly has started a serious relationship with — in her bedroom, which triggers Elliot’s off-kilter behavior. She crawls, catlike, over the large kitchen island, picking up food that has been left there.

There was a 5-foot-long fixture hanging over the island that was rigged with hybrid LED tape, creating a soft bounce off the countertop. Above that, production design built a skylight, and DMG Maxi panels provided a soft ambiance. “At other times,” Velez says, “if we were getting in close to Rachel and wanted to get a half-light or something tiny for the eyes, we would use DMG Minis and add Magic Cloth — sometimes up to four layers.” These additional layers, adds Velez, provided a “super-soft light — almost shadowless.”

Velez adds that the lights could be running at only 25 percent output, which is all they needed shooting with the Venice at an exposure index of 6,400 ISO in the 2,500 ISO base mode. That capability was a primary reason Lipes chose the camera, after having experimented with it on the Netflix movie The Good Nurse, on which Velez served as gaffer.

“Besides making the digital image noisier and less plasticky, you can achieve a light quality unlike anything I’ve seen before, because the foot-candles you’re working at are insanely low,” Lipes says. “You can use smaller units that you can get into smaller places, and you can diffuse more than you ever thought possible and create incredibly soft light.”

Lipes wasn’t afraid to be dim on the characters while lighting through windows. “Everything doesn’t need to be visible all the time,” the cinematographer says. “As a DP, you ask, ‘Can shapes or blocking tell the story?’ I always start from that place — but particularly on this show, I was trying to create a mood.”

Gonçalves’ episodes open things up visually, especially in the spacious birthing center. “We had an overhead ‘oculus’ — an [opening in the] ceiling about 3 1/2 feet in diameter — in every room with ETC SolaFrame 3000 moving lights above it, so we were able to control the intensity and light quality via light-board operator Bill Hopkins,” she says. “And then we had all the practicals and wall fixtures. I started infusing more color and doing more with primary colors. Jody introduced red in the lighting, and that became a huge motif for the rest of the series. I also brought in incandescent lights, just because I love using them.” These included beam projectors, 20K fresnels, and covered wagons with 60-watt and 100-watt tungsten filament bulbs. The crew also added incandescent Dedolights to the mix, providing bounces off surfaces such as countertops and adding book lights for a key as needed.

Regarding creative handoff from Lipes to Gonçalves’, Velez says, “Two DPs, two great people, and they both brought themselves and their talents to it, and maintained an integrity to the lighting, visuals and camerawork. It was awesome.”

Varying the Glass

Lipes paired the Venice camera with Panavision G Series anamorphic lenses. “Sean thought it was right to make it stylized and push beyond reality,” he says. “The 2.39:1 aspect ratio helped heighten that.” He stuck mostly in the 75mm-to-100mm zone, opting occasionally for the 60mm and the 50mm for wide shots — and also often used Panavision’s anamorphic ATZ 70-200mm T3.5 and a 50-500mm.

Gonçalves added a couple of H Series spherical primes for establishing shots of the research center in Episode 3, noting, “I wanted a slightly wider lens that matched the Gs and gave [visual-effects supervisor and producer] Eric a little more detail to work with for those shots. In Episode 5, four characters — the twins; Rebecca (the twins’ cold, billionaire investor, played by Jennifer Ehle); and the latter’s wife, Susan (Emily Meade) — travel to Alabama to open a second birthing and research center, and meet Susan’s old-school family. “[Showrunner] Alice and [director] Karyn wanted to make that feel like a whole different world, a different time and space,” Gonçalves notes. “So, I folded in some Primo Artiste [spherical] lenses, which are really warm and faster than the Gs.” They come into play for a dinner scene in the family mansion, during which Susan’s father discusses his pioneering efforts in the field of fertility. Gonçalves also used the production’s Panavision anamorphic zooms for occasional slow-zoom moves, which created an unsettling effect.

The mansion — shot on location in Long Island — offered an ornate chandelier for the dinner sequence, which is mostly lit with candles on the table and around the room. Velez’s team augmented them with small plastic ceiling globes mounted on base plates and affixed with LED tape and hidden around the table. For close-ups, they would come in with DMG Minis with flag cutters armed on a boom.

Surreal Sequence

In a dreamlike sequence later in the episode, Beverly is woken by strange moaning sounds, and follows them down to the mansion basement, illuminating her way — and for the viewer, her face — with a lantern. The lantern’s warm glow contrasts with an ambient deep-lavender color generated by the overhead Lumière LEDs, some coming through a skylight, engulfing the entire set.

She enters the basement, only to be surprised by a ghostly Black woman kneeling on a table who recounts a story of gynecological experiments inflicted on a slave girl. Beverly’s perspective of the room is dark — it was shot on a black-box stage with a reflective floor — save for the ghost, who is lit by a practical, fluorescent-style fixture that was fitted with a DMG Lumiere Maxi above the table. When she stands up, she is in the ambient light, and then a DMG Mini cue light shines on her face. At the end of the sequence, interactive lights from a moving truss dim on and off behind her before the scene fades to darkness.

“We experimented with different lighting,” Gonçalves says. “We did a full red pass and a silhouette pass, but ended up using a normal-light pass until the end — where we punctuate her final line of dialogue, while everything dims out. One of the great things about this show is all of the experimenting we were able to do.”

TECHNICAL SPECS

2.39:1

Cameras: Sony Venice

Lenses: Panavision G Series, H Series, Primo Artiste, ATZ

Glowing Colors

Colorist and ASC associate Sam Daley, from Light Iron in New York, is another longtime collaborator of Jody Lee Lipes ASC who joined him on Dead Ringers. They used a LUT that Lipes had developed over the years through many commercials, which they adjusted for The Good Nurse and then again for this series.

“The idea is to help stuff in the lower luminance range go slightly cooler, and stuff in the higher luminance range go warmer — [and adding] low contrast, milky blacks,” Lipes explains. “It’s a gentle image — not too saturated but pushing the color contrast. It really helps that delineation between shadows and highlights.” Gonçalves worked with Daley to modify the LUT, keeping in mind the series’ visual evolution and increased use of color.