The Filming of Forbidden Planet

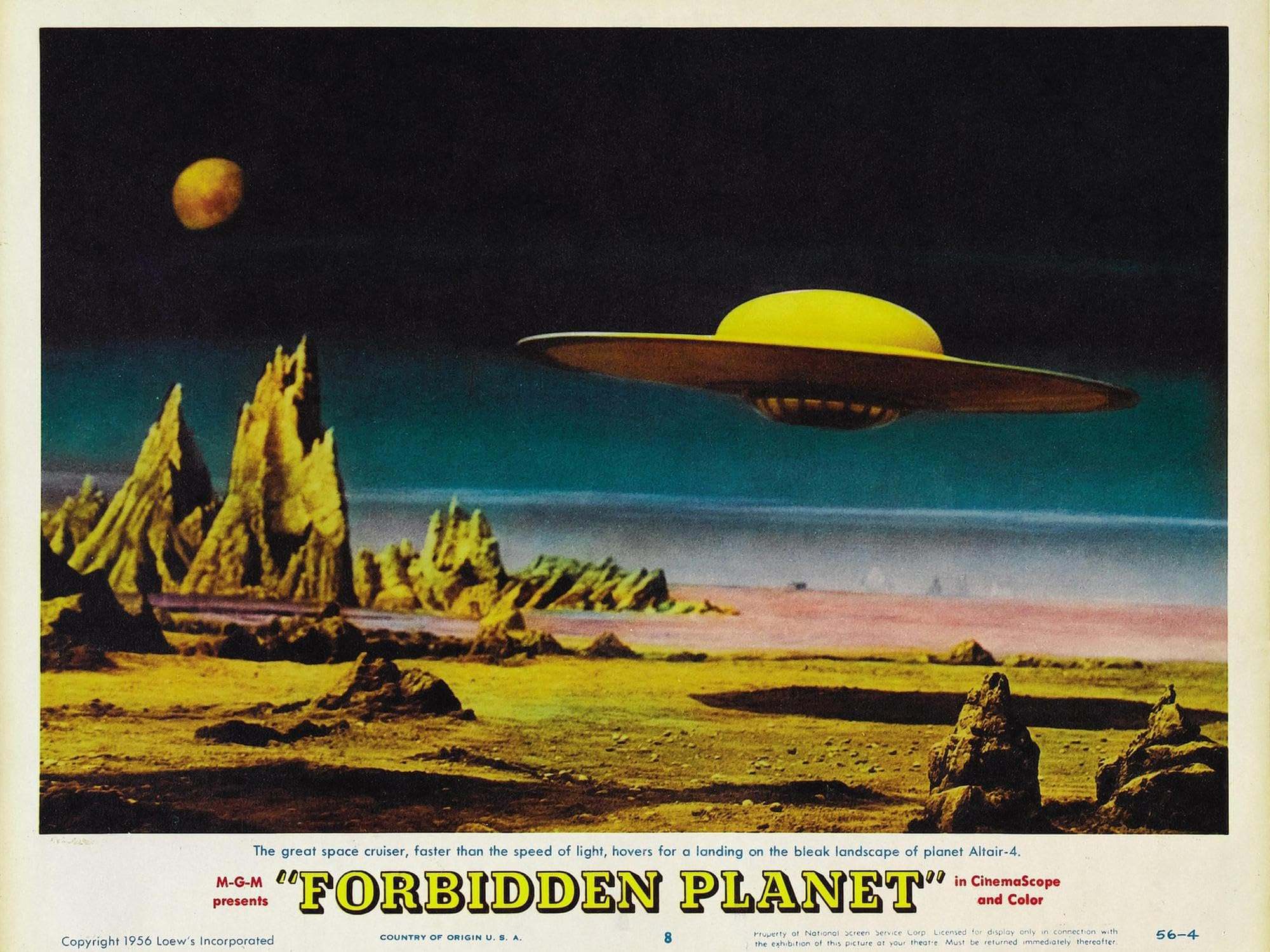

The most ambitious science-fiction thriller yet filmed, this MGM production called for use of every cinematographic trick in the book.

This article was originally published in AC Aug. 1955. Some images are additional or alternate.

When I was assigned to direct the photography of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s science-fiction thriller Forbidden Planet, I was faced with two unique problems: photographing a new star — a mechanical robot nearly seven feet tall — and lighting the futuristic settings of a fabulous land never before seen on the screen.

Locale of the story is a mythical planet millions of miles in outer space, where the sky is of a strange green hue and where an invisible monster prowls the desolate terrain. All sets, of course, were built on the sound stage. The story is set in the year 2200 AD., and stars Walter Pidgeon as a scientist, and attractive Anne Francis as his daughter, with a newcomer, Leslie Nielsen, making his screen debut as the hero.

“The entire photographic crew that worked with me is especially deserving of credit, particularly for the precise coordination of all hands, and the efficient, smooth way they worked when we had a problem to lick.”

— George Folsey, ASC

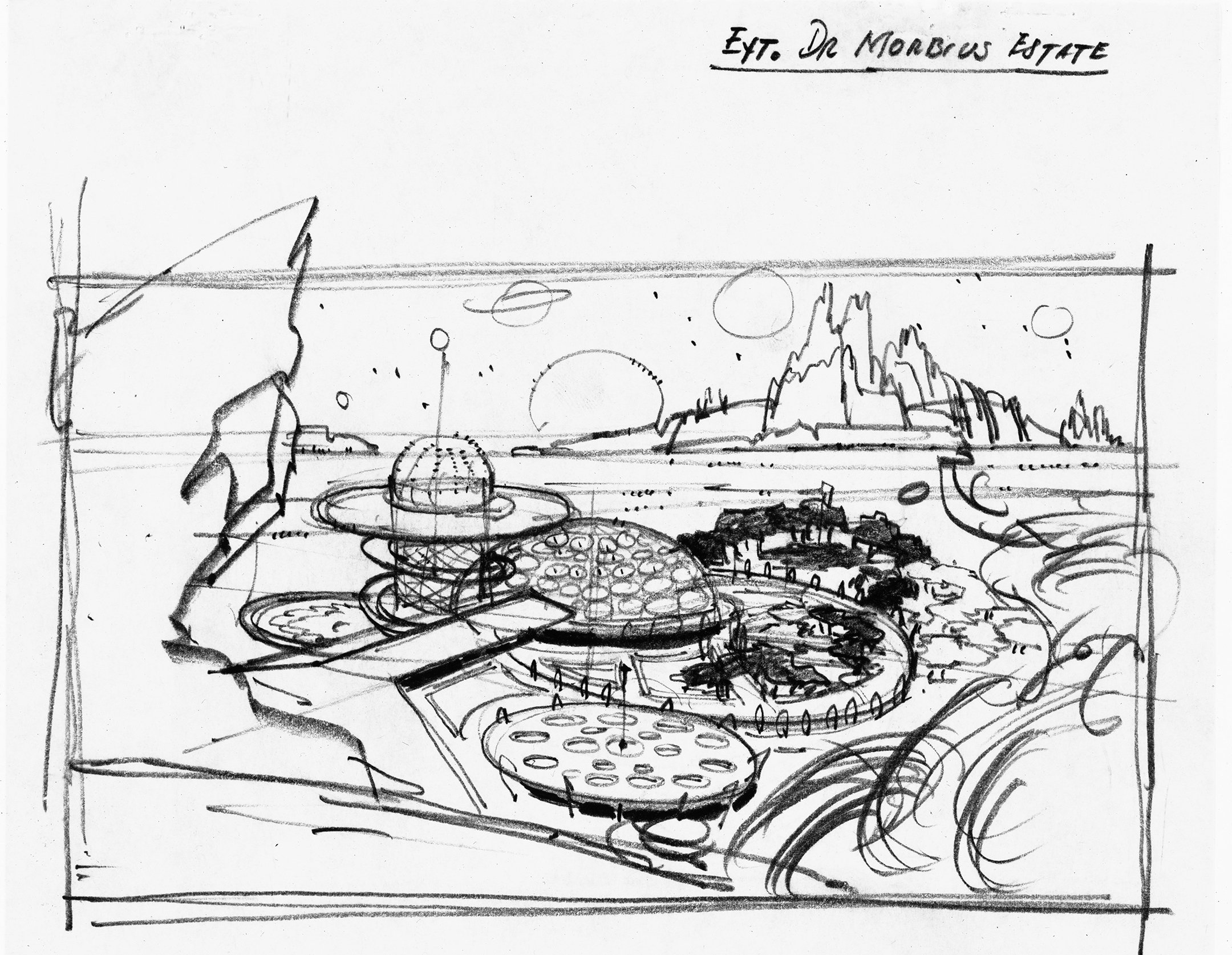

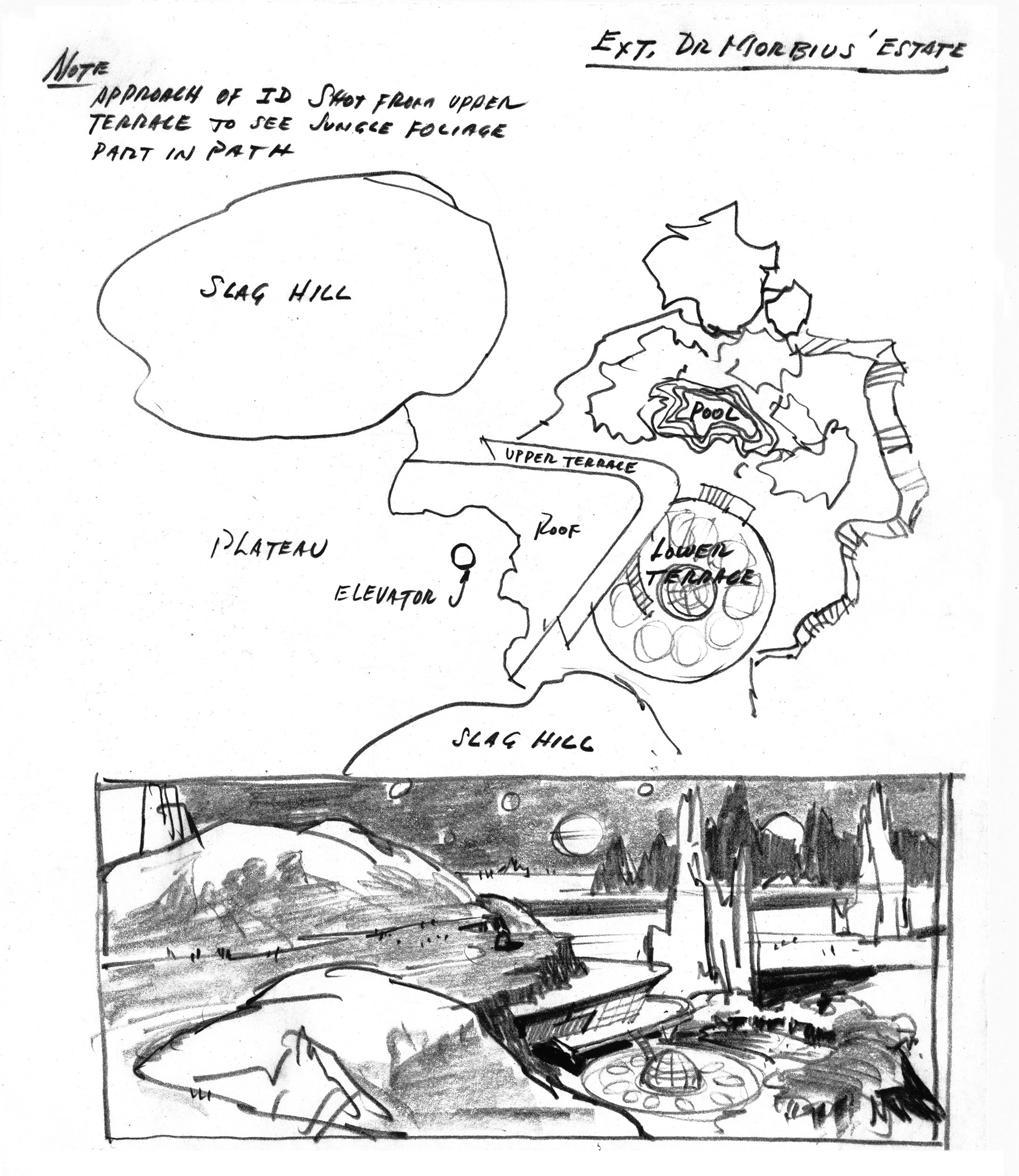

More than two years of technical research was undertaken on the production by the studio before it was turned over to producer Nicholas Nayfack and director Fred Wilcox. But research did not stop here. Actually, the important pre-production planning began when we started to visualize the sets and the action from the camera viewpoint. With a completely new subject and a locale virtually dreamed up out of fantasy, the production posed a fresh new challenge, photographically.

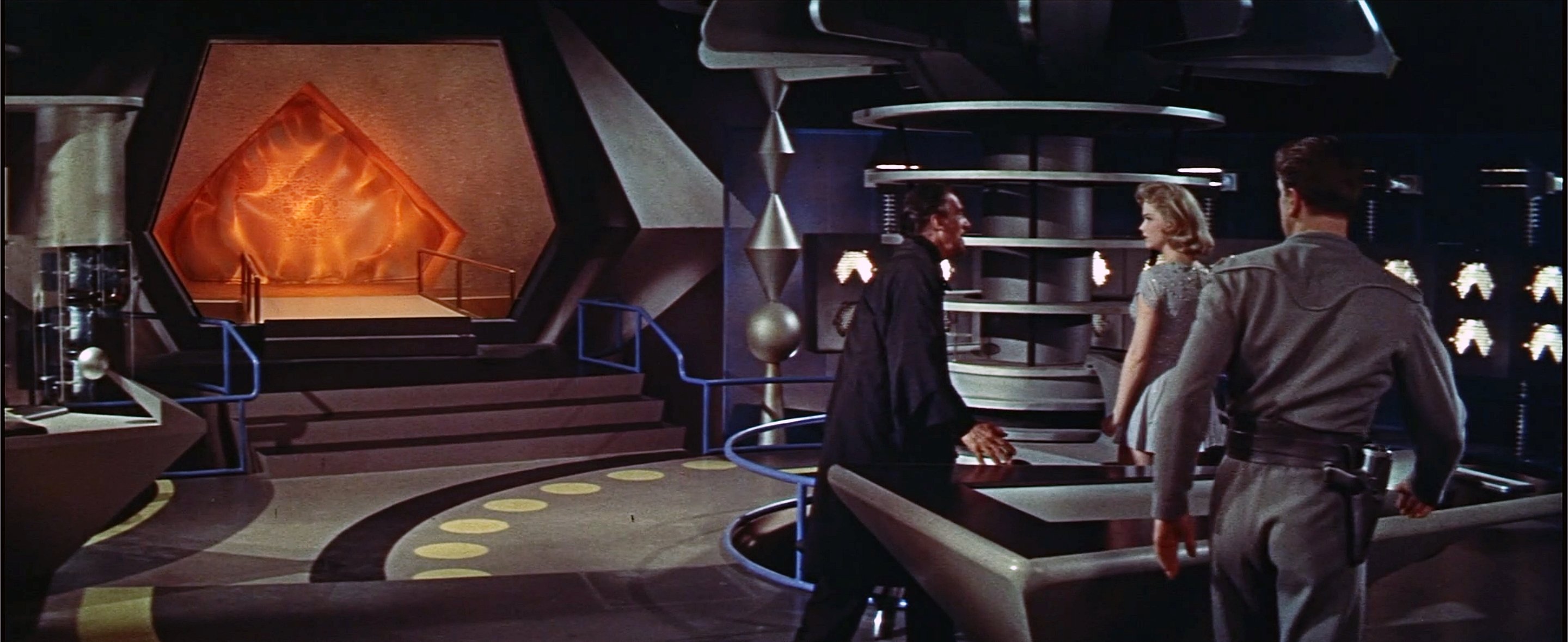

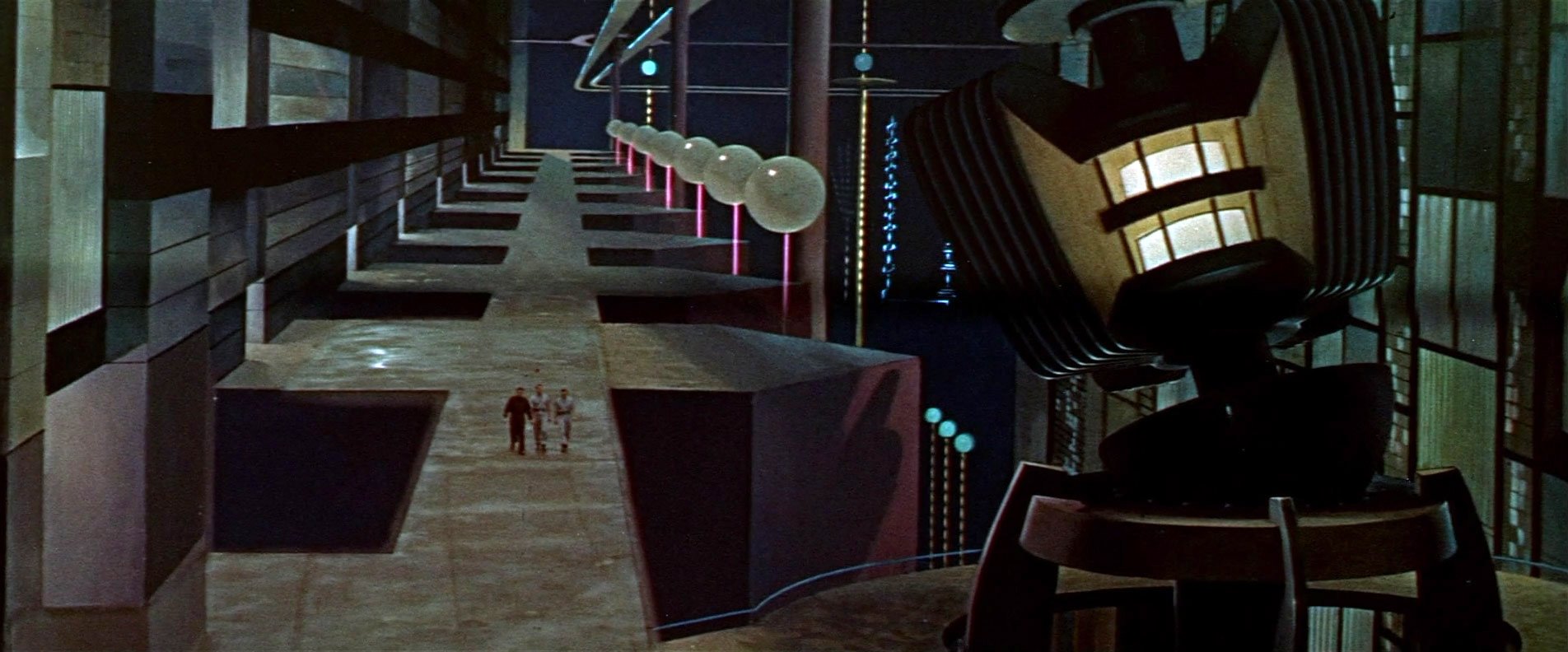

The photos below give the reader some idea of the unique sets which were prepared for the production by supervising art director Cedric Gibbons and art director Arthur Lonergan. Because so much of these vast settings — designed for CinemaScope and color film — comprised giant painted backdrops or cycloramas, the problem of matching the lighting, or achieving the lighting gradations, far surpassed anything that is encountered in the conventional type of production. [More detail on this process here.]

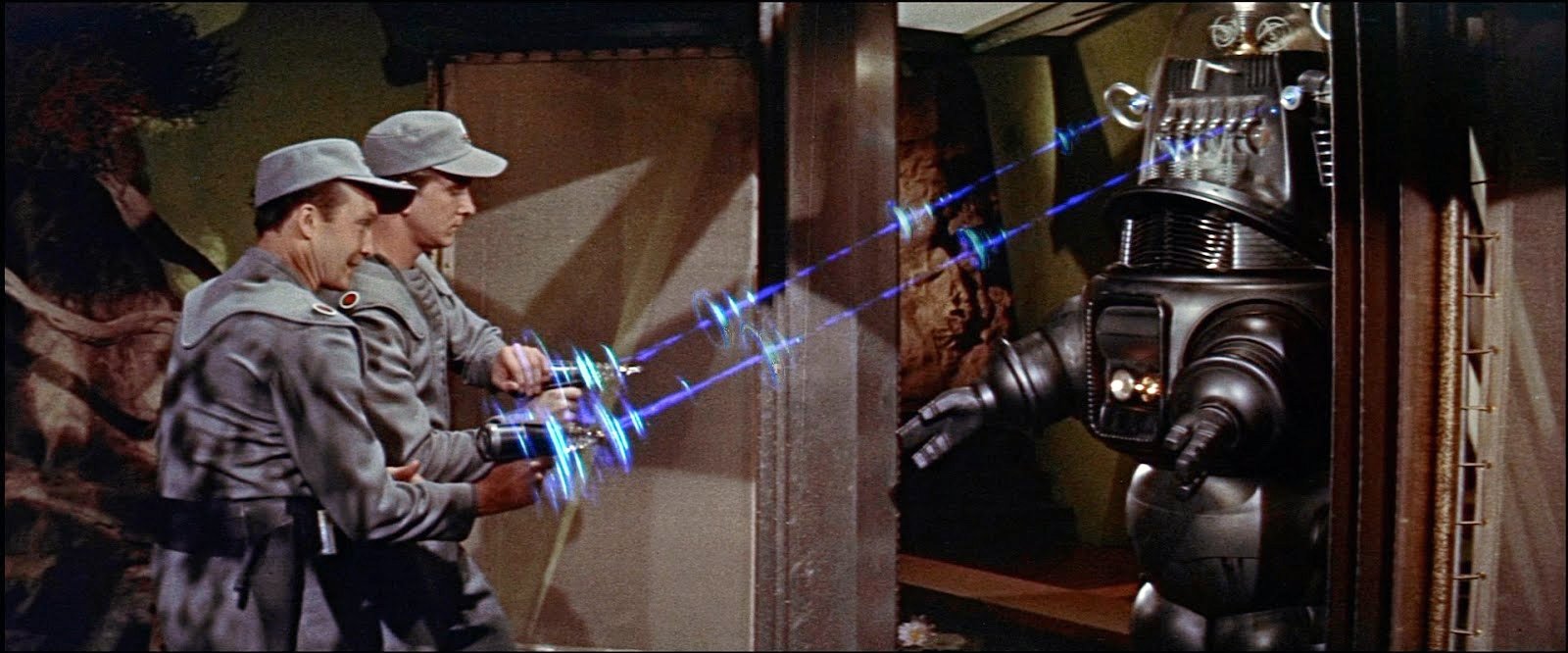

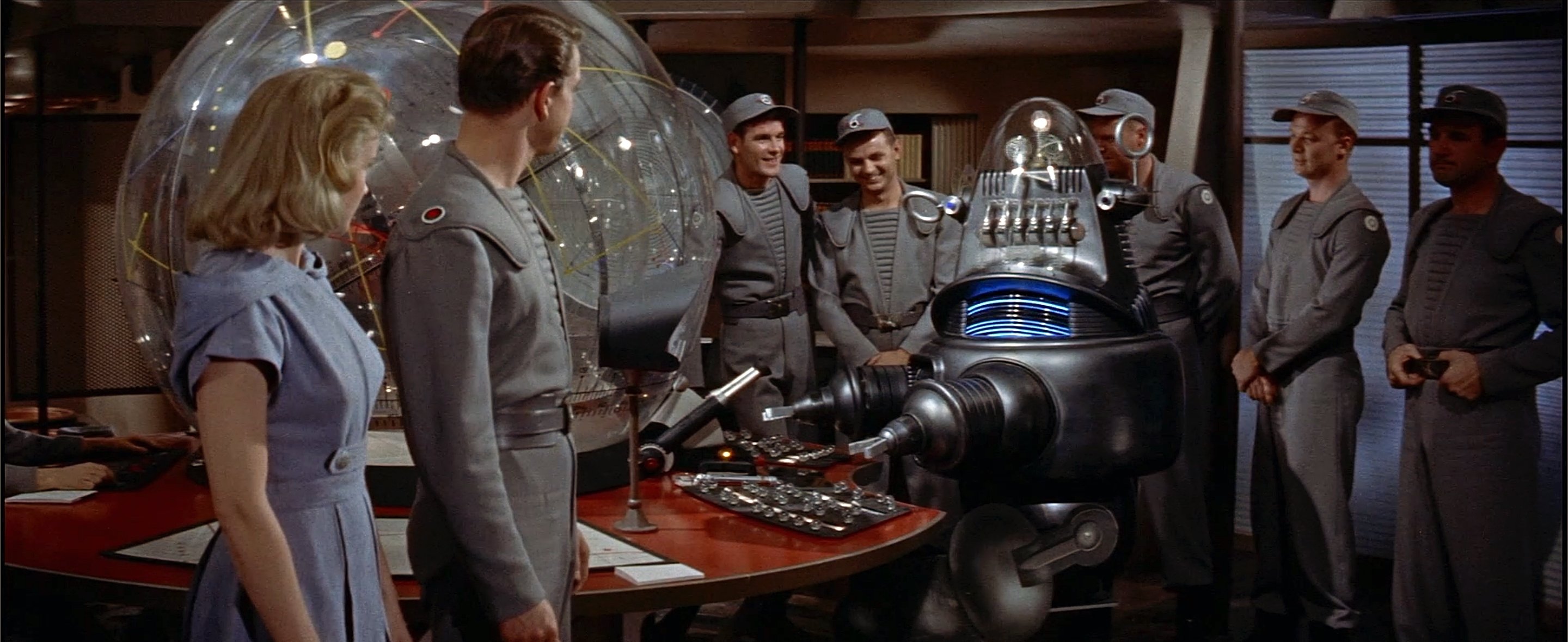

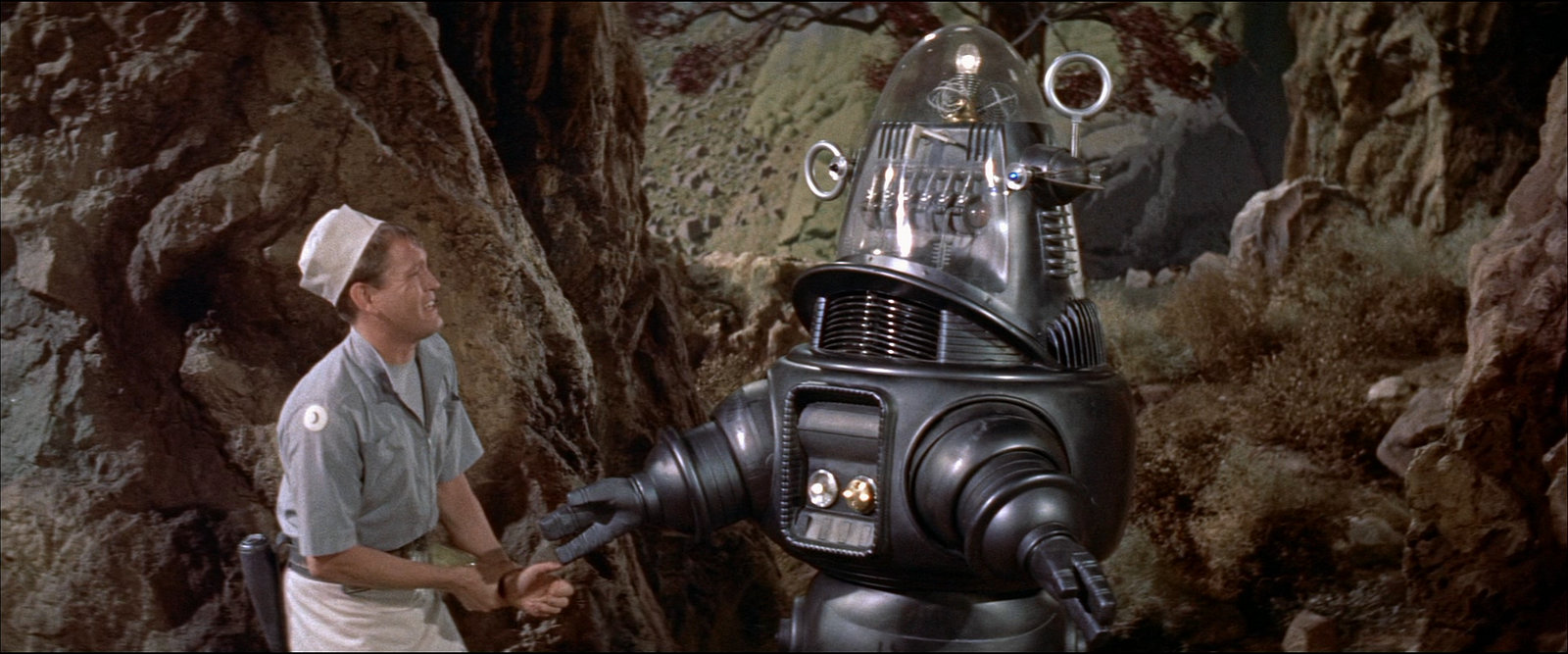

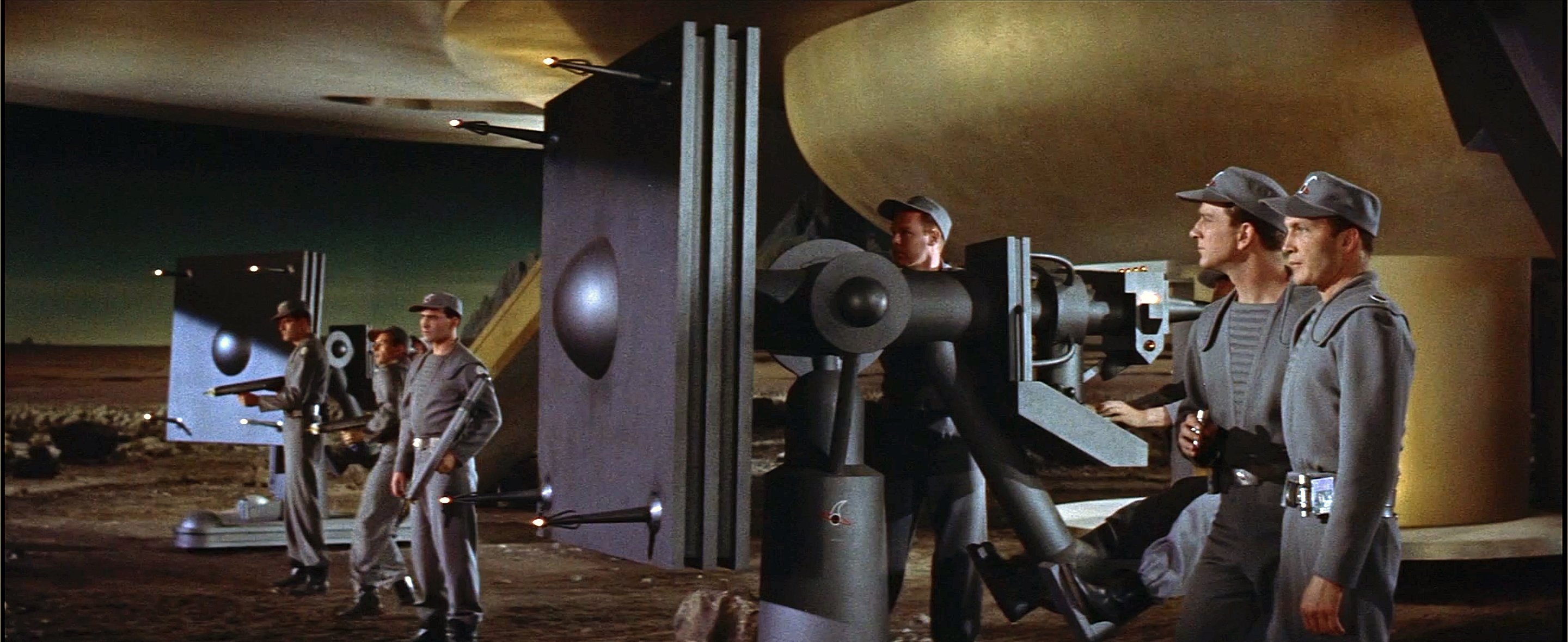

In addition to the sets, which required all the floor space of four of the studio’s largest sound stages, mechanical wizardry and prop-shop skill had brought forth the most unusual of science-fiction innovations. Important props included an atomic cannon, a space Jeep, an electromagnetic tractor, and the picture’s most entrancing personage, Robby the mechanical robot.

The robot’s massive body was motivated by six electric motors, and was controlled through a complicated switchboard panel. He had complete mobility of arms, legs and head. More than two months of trial-and-error labor were required to successfully install the 2,600 feet of electrical wiring that made the robot independent and self-operating.

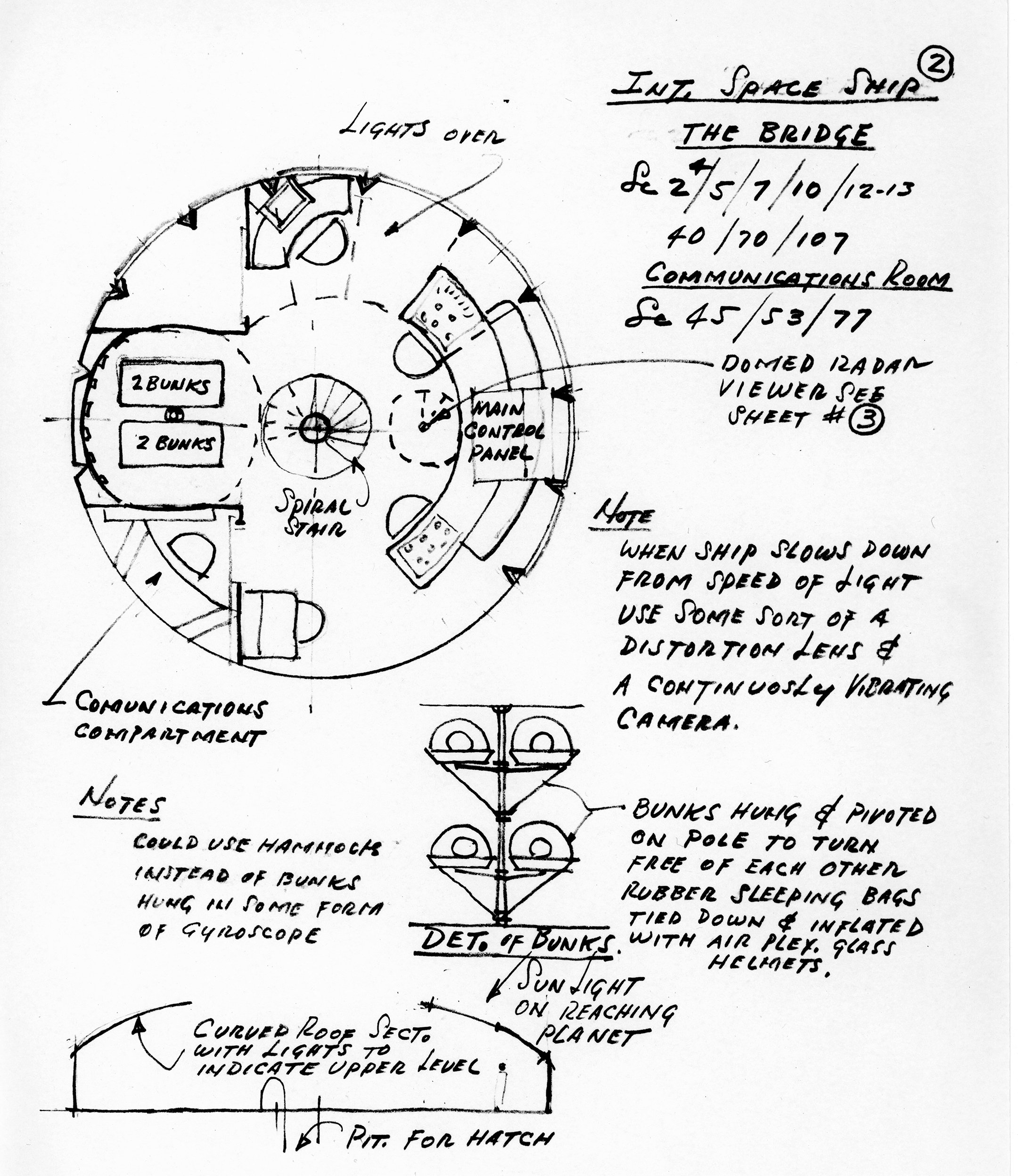

A crew of 19 men worked a month to install the 27 miles of electrical wiring used in the control cabin of the space ship. In order to be able to successfully control the extensive illumination for this one set alone, a set-lighting switchboard was set up and manned by a score of electricians.

Biggest bugaboo, perhaps, on this picture was the ever-present reflection of light. The fantastic, modernistic sets of bright metal and plastics bounced light in almost every direction. An example were the “deceleration chambers” — large tubular plastic cells — into which space ship crew members must enter for a period of time when subjected to sudden change in atmospheric pressures — much as “sandhogs” and deep-sea divers do after subterranean or submarine tasks. So, in addition to meeting the problem of getting adequate light on the set, we then had the problem of so placing it or masking it as to keep it from bouncing off the bright surfaces and into the camera.

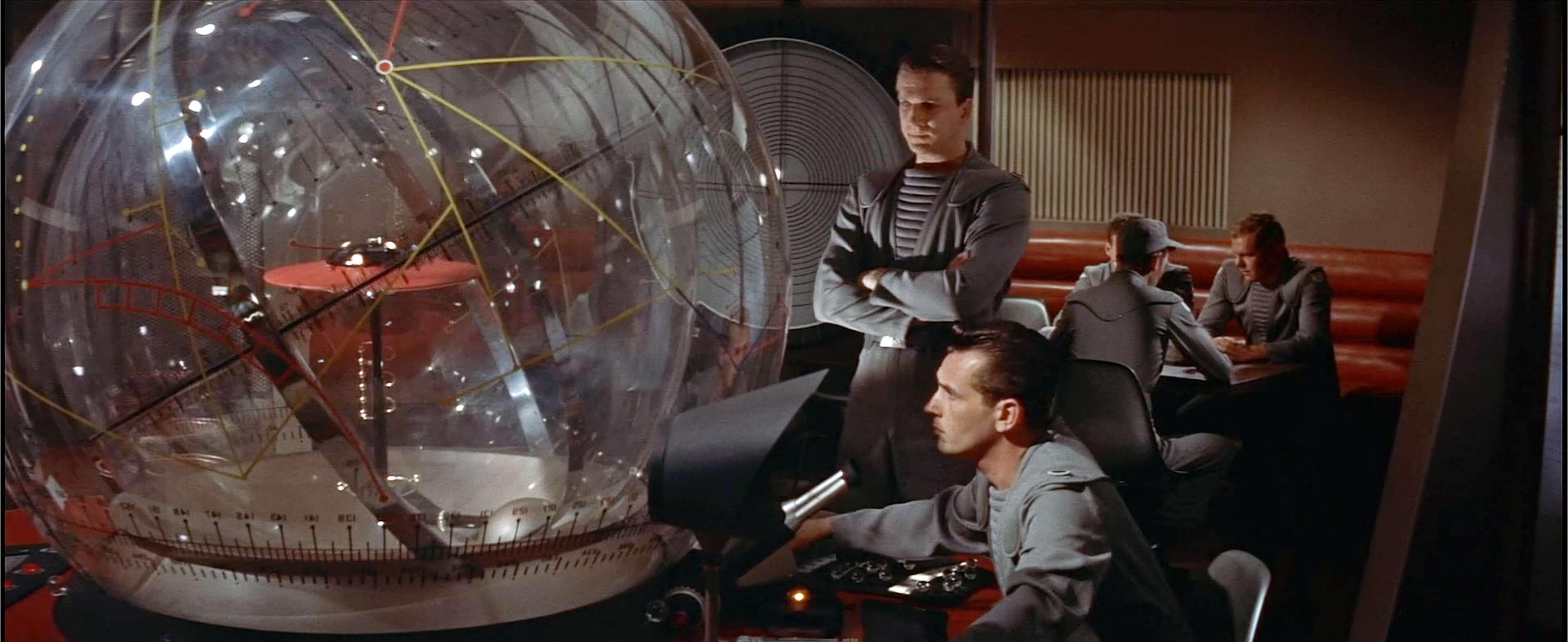

Equally challenging was a large plexiglass globe in the center of this same set. It measured nearly 16 feet in circumference, and enclosed a smaller globe within it which was surrounded by two bright steel bands as a decorative feature. It seemed for a time that it would be impossible to light this globe in a manner that wouldn’t reflect light. The solution was achieved by painstaking effort in changing position of the set lamps and by careful masking until the desired result was obtained.

Much of the set materials was also reflective with the result that we continually picked up reflected light around and in back of people. Here, again, the obnoxious bouncing light was neutralized by studied placement of set-lighting units.

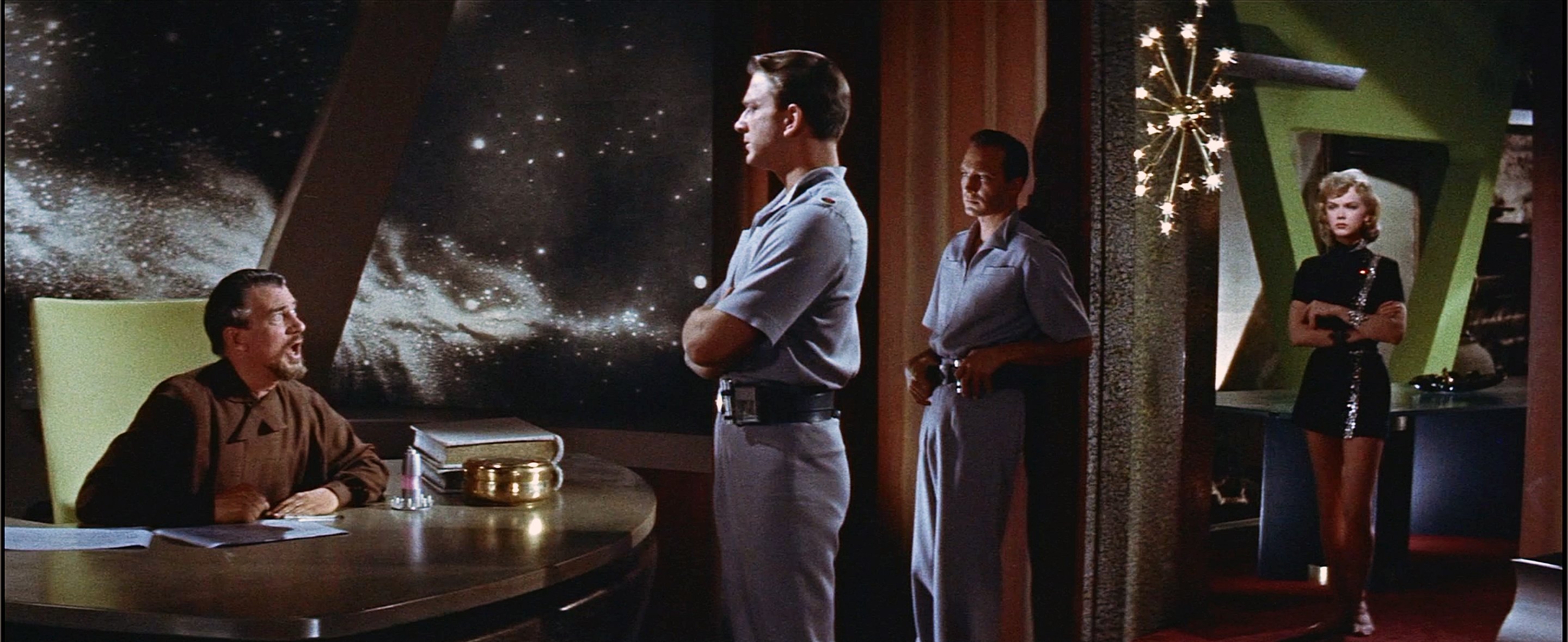

When it came to shooting scenes in the control cabin of the space ship, we encountered a fresh new batch of problems. The cabin was a maze of radar screens and luminous dials, blinking and vibrating. We had to carefully control our lighting here so that some instruments would not shine too brightly while others would shine through the darkness and not be lost on the screen.

The real lighting and photographic creation for this production, however, was the weird and spine-tingling invisible monster that creeps into the control center late at night while the crew sleeps soundly in their bunks. While this was something of an effect, it had to be created with light and given a semblance of form. Through an arrangement of special lighting, shadowing and use of color, we produced a most unusual effect on film. And by using several well-established photographic techniques, such as shooting from a moving camera crane elevated to a height of 10 feet, the effect achieved was that of showing the scene as seen from the giant monster’s eyes.

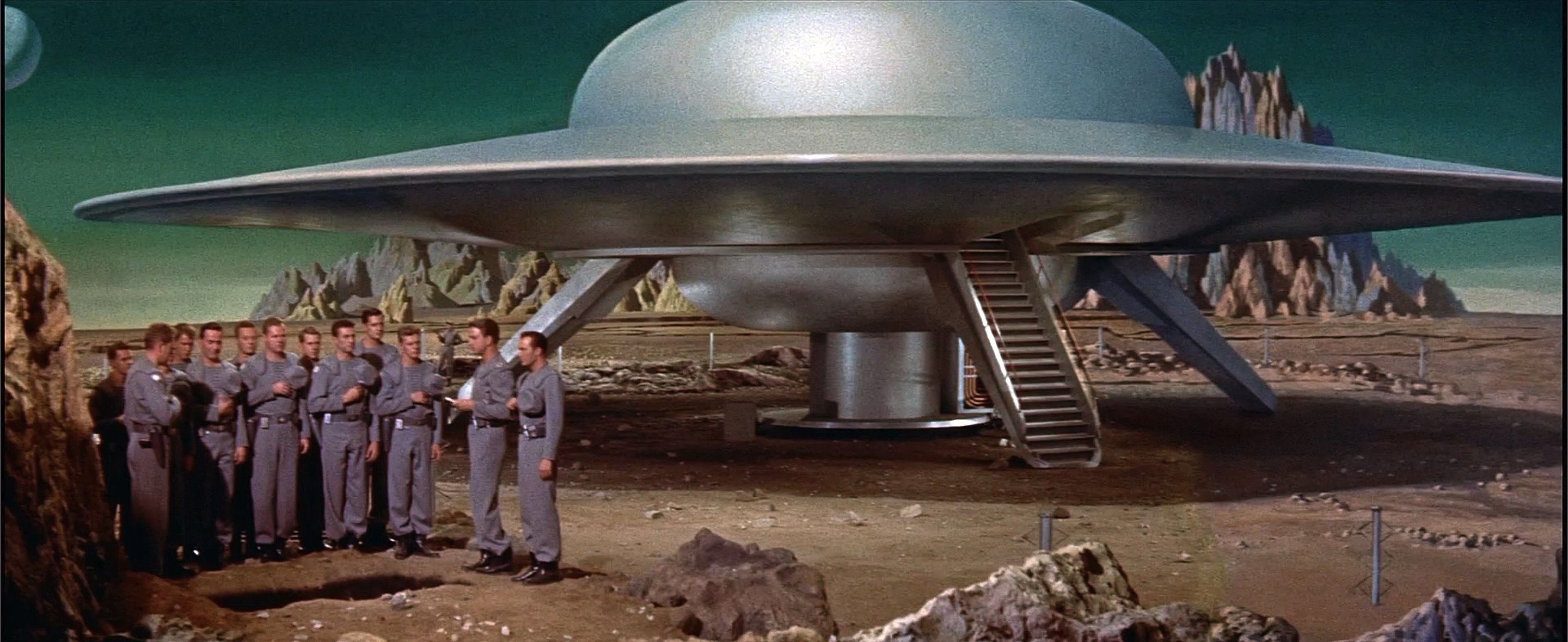

There were more challenging problems awaiting us when we moved over to the immense space ship set on Stage 15. Supplementing this set was an enormous painted cyclorama, 350 feet in length, hung in the background. It was here that particular care had to be given set lighting — first to make sure that the light source direction matched exactly the lighting depicted in the painted cyclorama. Any error here would easily suggest where the constructed set left off and the painted backdrop began.

Here we used 40 of the MGM-designed Skylights, each holding 10 1,000-watt photo lamps. These were augmented by 96 10,000-watt K-10’s and 192 K-5’s. Auxiliary power lines were run in from adjoining sound stages to furnish the unprecedented current load for this vast array of lighting equipment.

On this set, I encountered several lighting problems which were not easy to solve. First, the silver finish of the huge space ship reflected light like a mirror. Secondly, we encountered difficulty in silhouetting the saucer edge against the sky because the sky in the background was dark green above, graduating to light green toward the horizon. We couldn’t light from below the set because it would reflect; our final solution was to hide an occasional “Senior,” “Junior” or “Midget” lamp behind convenient set elements and props, thus lighting the saucer from the interior of the set itself. I think this was perhaps one of the most interesting set lighting problems I have ever been called upon to solve.

Still another problem was that of shooting scenes on this set at night, when the backgrounds had to emphasize a pronounced eerie tone. In one of the night sequences, the invisible creature attacks the flying saucer and its crew while undergoing a barrage of tracer fire from atomic weapons.

I illuminated the lonely desert setting with 500 foot candles as effect in the foreground and put 54 foot candles of light in the background. We had to imagine the monster, how bright he blazed, and how undulating his fiery outline would reflect around him. Much of the desired effect was achieved by putting colored filters over the arcs. Incidentally, red is not the easiest color to reproduce, and an invisible villain not the easiest to record on film. So it was difficult to get a perfect take of Nothing! To effectively photograph scenes indicating the approach of the invisible monster as he headed directly for the camera, I employed 62 10,000-watt arc lamps and 32 K-5’s to light up the mythical planetary desert with absolutely no one visible. The effect of the monster’s approach was achieved by changing the lighting in a predetermined pattern, using Venetian-type shutters over each arc. Several onlookers on the set said they actually felt the invisible visitor pass in front of the camera, so realistic was this lighting effect.

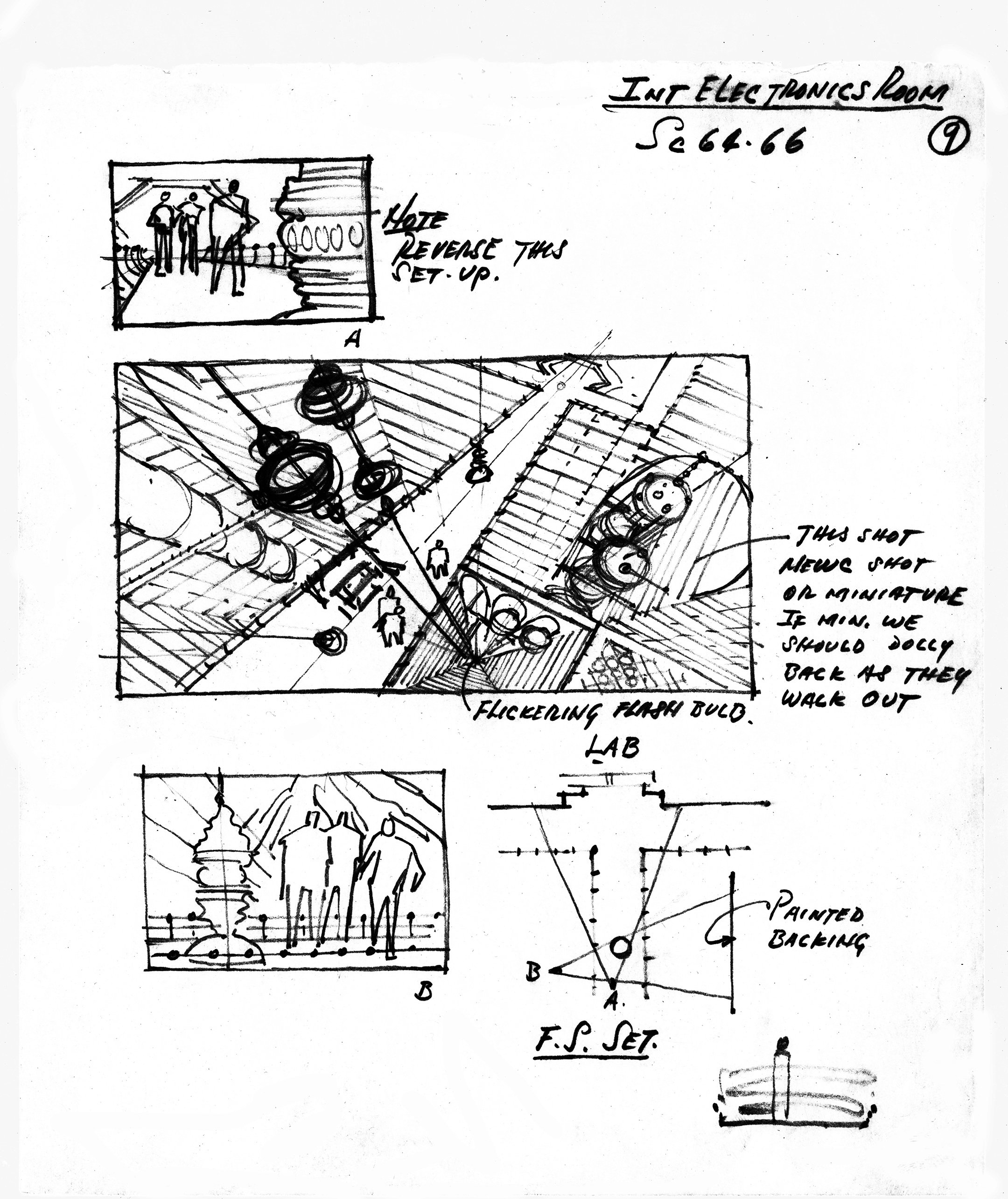

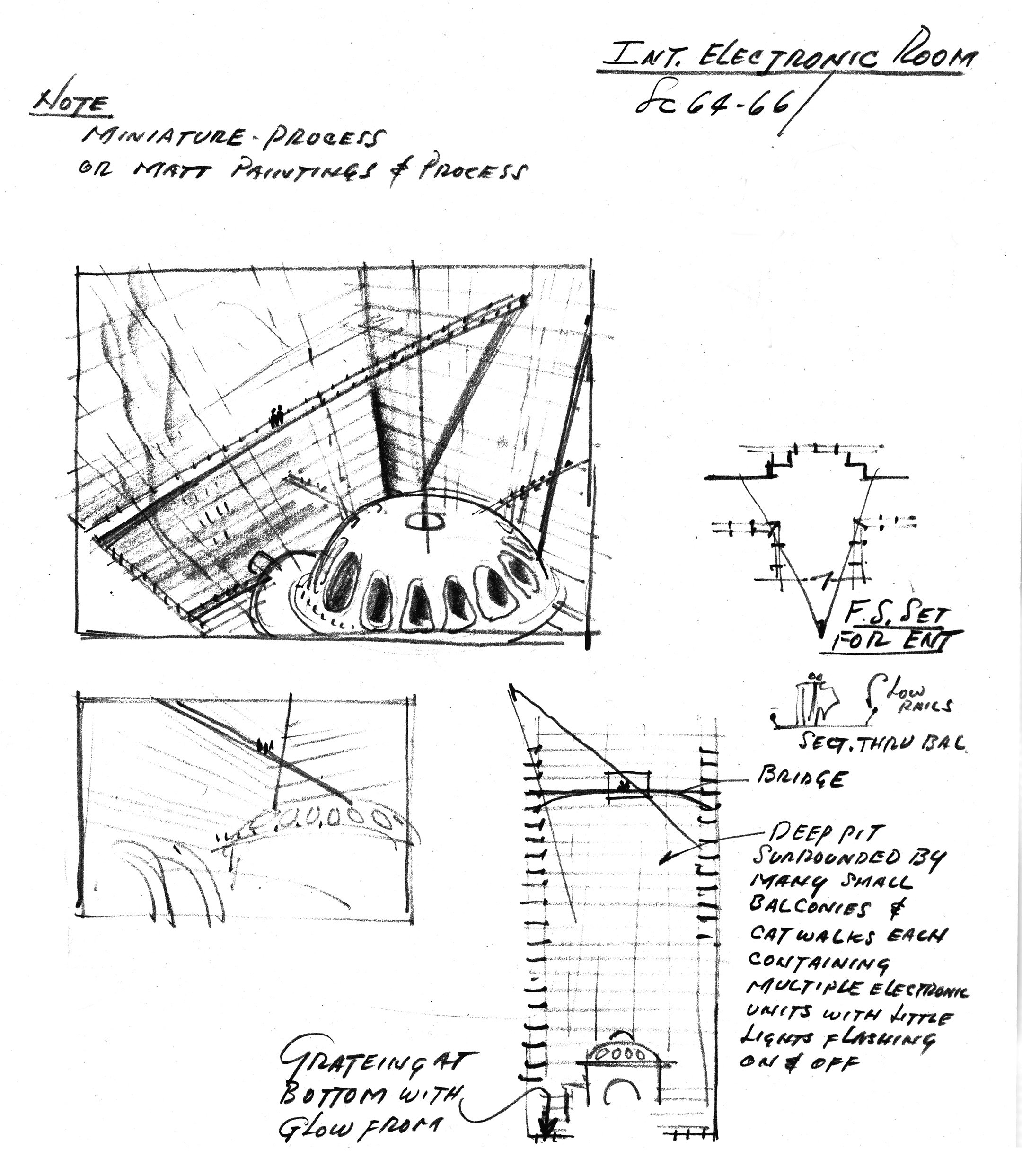

Another elaborate set for Forbidden Planet was the electronics laboratory. This required 50,000 feet of wiring, 2,500 feet of neon tubing, and 1,200 square yards of plexiglass in its construction. To achieve precise lighting on this set during shooting, a staff of 15 electricians handled 110 separate switches on a giant control panel.

Ever-present light reflections continued to plague us on this set, too; but by this time we had gotten down to a fine science the technique of changing the light and dulling bright surfaces with wax to lick the problem.

On the lab set we shot one of the longest scenes ever filmed in CinemaScope. It ran continuously for 9 ½ minutes, and entailed more than six pages of dialogue. In one single unbroken take more than 1,300 words were spoken while our camera, mounted on a mobile crane, made 16 different moves on cue, shortcutting the necessity of having to make an equal number of separate setups.

It was on this set, too, that we photographed one of the production’s most exciting sequences when the diabolical monster, in a spine-chilling climax, breaks through four huge steel doors to face its creator, Dr. Morbius.

One of the largest sets for the picture, and one on which a great deal of important action takes place is the “House of Tomorrow,” the residence of Dr. Morbius and his daughter. In erecting this set, novel use was made of glass, metal, plastics and synthetics. The structure was erected on slender V-shaped legs that gave it the maximum of substantial support with minimum of material. Large, built-in screens of fine gold mesh separated the various rooms. The living room was divided by large panels of clear Lucite. Most of the ideas that went into the design of the house were not based on fantasy, but are an extension of current thought, both architectural and electronic. Nevertheless, it all presented a host of new lighting and camera problems, creating a constant challenge to the photographer.

The entire photographic crew that worked with me is especially deserving of credit, particularly for the precise coordination of all hands, and the efficient, smooth way they worked when we had a problem to lick. Especially is this true of Irving Reis, ASC and Max Fabian, ASC for their wonderful cooperation and help in the execution of the optical and photographic effects for the production.

Incidentally, Forbidden Planet is not my first encounter with a science-fiction production. “Way back” in 1922, I photographed a thriller for Biograph Studios in New York titled The Man from M.A.R.S., featuring unearthly creatures with huge heads and gleaming talons. I shot the production in black-and-white in a “new” process they called 3-D! I recall that most of the picture was shot at a stop of f/8, and without the benefit of an exposure meter.

Forbidden Planet in color and CinemaScope is a far cry from this early Biograph production. For me it has been one of the most “off-beat” camera assignments I have ever undertaken since joining the MGM camera staff in 1932.

Folsey’s other credits include Meet Me in St. Louis, Gentlemen of the Press, the Marx Brothers comedies The Cocoanuts and Animal Crackers, and Seven Brides for Seven Brothers.

He was the first recipient of the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award, presented in 1988.

A member of the ASC since 1927, Folsey served as Society president in 1956-’57. After he retired in 1976 with 162 screen credits to his name, he went on to lecture at the American Film Institute. He died on Nov. 1, 1988, in Santa Monica, Calif., just eight months after being honored by the ASC.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.