Seven Brides for Seven Brothers: Simultaneous Production Shooting In CinemaScope and Widescreen

There’s always something new being tried in the making of MGM productions, and this was no less true when two cameras were used for every shot and gaffers communicated via short-wave radio.

All MGM photographs by Frank Shugrue

Back in 1922, I had the pleasure of being associated with director Chester Franklin at the old Long Island Studios, working mostly with Bebe Daniels on such memorabilia as Nancy From Nowhere and Rum Runners.

I mentioned this biographical fact not to establish how long I have labored in the celluloid vineyards, but to bring up an interesting discovery made at that time, viz.: that fog — the variety that creeps up New York's East River — is one of the greatest aids in light dispersal, producing soft values in illumination which, I have also discovered, are ideal for CinemaScope photography.

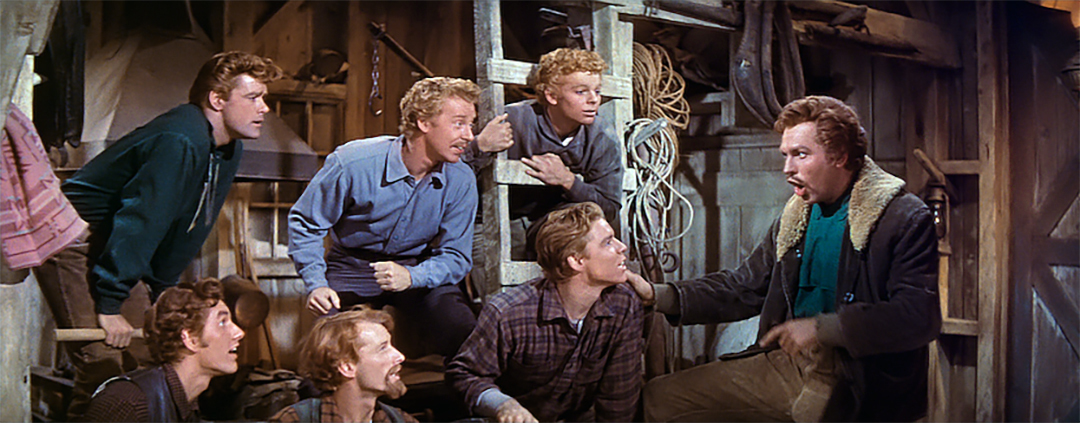

So, when I was assigned recently to photograph MGM’s CinemaScope musical Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, produced by Jack Cummings, my earlier experience with fog stood me in good stead. In starting to shoot this production, certain problems in set lighting soon made themselves apparent — namely, that created by the much wider CinemaScope aspect ratio and the unusually large cast of principals, 14 in all. At times more than 20 featured players were on stage at the same time — a matter that posed a problem of lighting them all adequately and uniformly.

By contrast, for the intimate love scenes in which were paired Howard Keel and Jane Powell, Jeff Richards and Julie Newmeyer [who later became Julie Newmar] and all the rest of the newly wedded couples — all prominent in the picture — the CinemaScope area in the camera finder loomed as empty as the Rose Bowl on January 2 when setting up for closeups or medium shots of the individual couples. Here, the compositional and lighting problems were to make unobtrusive, without being obvious about it, those parts of the wide CinemaScope picture area left open when action was concentrated in the middle of the screen.

The solution was in strategic placement of kickers and sidelights, all rigged to produce reflected or diffused light — similar to the soft quality of fog-diffused light I had discovered years earlier. Actually, this lighting technique, now widely used by many cinematographers, is the single innovation of no one man. If any credit is due anyone for this pictorial innovation, it should go to Leonardo da Vinci (see his Mona Lisa) and others of the Old Masters; for although it may not be apparent at first glance, such artists virtually swept their entire canvas with diffused light.

I once used this technique of diffused light during the entire production of If Winter Comes, and for many sequences in Green Dolphin Street, lighting through silks.

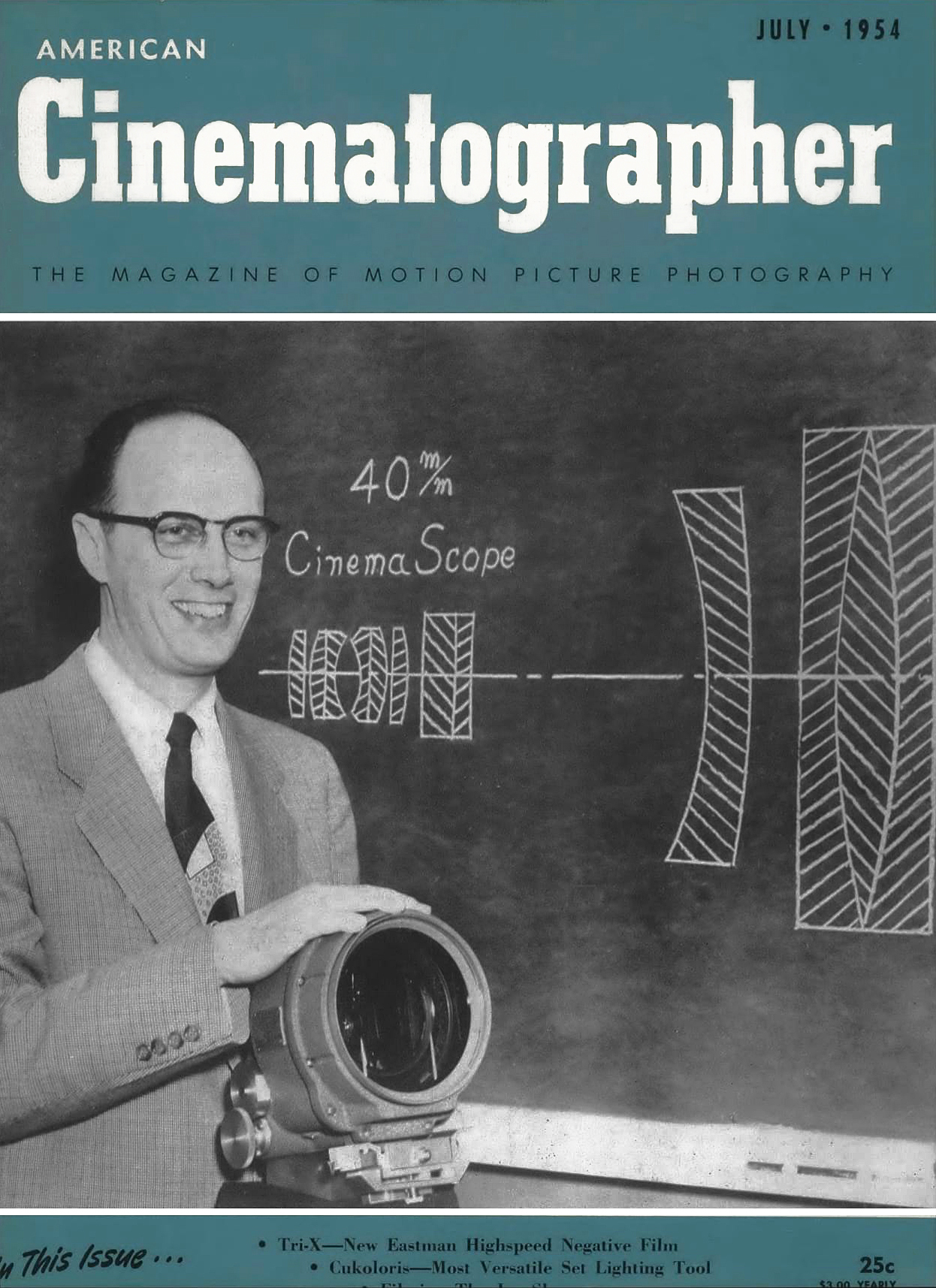

Problems on Seven Brides for Seven Brothers began with the word go. The picture was being shot in two aspect ratios: CinemaScope [2.55:1] and widescreen [1.75:1], which required shooting about 90 percent of the scenes simultaneously with two cameras — one for each format.

The opening sequence encompassed almost continuous action on a set three blocks in extent erected on MGM’s back lot. Howard Keel, singing one of the hit tunes in the picture, strides up and down the sidewalk in search of a girl — “any girl!” This vast set was successfully lighted for widescreen photography by mounting arc lamps high on parallels erected on the opposite side of the street. Key lights were mounted on the camera car that moved along the street and followed the singing Keel.

Some indication of the production scope of Seven Brides for Seven Brothers may be seen in two vastly differing sets used in the picture. One took up the entire 23,000 square feet of MGM’s Stage 29. Dressing rooms, makeup tables and mirrors, and all spare equipment normally fringing the sets on a sound stage had to be parked outdoors. In the corridor between the stages, special “big top” tents were erected to house the makeup and wardrobe facilities, and trailers were parked nearby to provide accommodations for the cast.

This huge set, erected for the “Barn Raising” sequence of the picture — actually a combination of old-fashioned hoe-down, barn raising, and a spectacular free-for-all brawl — called for nearly a quarter of a million watts in lighting, more than used on any previous MGM film. Twelve overhead batteries of skylights, each holding in its aluminum reflector and 10 1,000-watt photolamps, were augmented by 85 K-10 lamps of 10,000 watts each plus 47 K-5s.

The tremendous heat generated by this great volume of light units kept the studio air-conditioning plant working overtime in an effort to keep the stage temperature at a workable level. Even so, readings of 98°F were common, but not popular, at center stage.

Such an array of overhead lighting equipment naturally posed a communications problem for gaffer Fenton Hamilton and his assistants and the electrical crew working on the catwalks overhead. This was met easily by Hamilton who employed a relatively new innovation of the sound stage — a compact miniature two-way radio system.

The transmitter, virtually a miniature radio station, consisted of a microphone, transmitter and batteries — the unit weighing around six ounces. Resembling a hearing aid case, it is worn around the neck. Speaking through the microphone, gaffer Hamilton’s instructions were broadcast and picked up by a series of 35 4-inch speakers spaced at intervals around the catwalks. The little broadcasting set has a carrying range of 600 to 800 feet — ample for use within the largest sound stage. The system was used earlier during the filming of The Student Prince and Brigadoon, shooting on adjacent sound stages. The transmitters on each production were set to operate at different frequencies to prevent one interfering with the other.

So sensitive are these tiny transmitters that the user need only speak in a whisper. An unitiated extra unaware of this, stopped me one day with the observation: “The gaffer has blown his top. Been talking to himself for the past hour!”

In shooting the big “Barn raising” sequence, our only problem camera-wise arose from the spectacular dance routines created by choreographer Michael Kidd — dances that were basically violent ballet. In a nutshell our problem involved keeping the dancers within camera range both vertically and horizontally. Much of this was accomplished by shooting from a very high angle or from ground level — especially when we had to capture the high leaps and acrobatics of some of the dancers.

By contrast, Stage 25 — where we filmed the mood number “Lament” — called for many controlled gradations of light. The setting was a snow-covered meadow on a dreary winter day — the number beginning in a gray overcast and gradually achieving full sunlight. Director Stanley Donen, in a last-minute decision, decided that we should film the entire number without a cut. This we did. The operation involved 17 camera moves, 80 feet of dolly track, and use of the studio’s large RO boom.

It worked beautifully, gave an uninterrupted “flow” to the number, nervous prostration to the operators, and called for a series of backstage signals rivalling anything ever dreamed up by Knute Rockne. Large shutters, resembling giant Venetian blinds, were hung from the catwalks in front of the set lighting units. Operated on cue, these provided a simple yet effective method of varying the light. On the screen this is a simple scene, apparently effortless, yet all six principals involved moved constantly to and fro over the entire set.

Shooting with two cameras — one CinemaScope and one widescreen — simultaneously on the same set involved little or no additional problems, except when shooting closeups, and then we would shoot with one camera, move out, and move in with the other for a duplicate shot. Setting up two cameras side-by-side takes a few additional minutes time, but the overall benefits are well worth the effort. Where it was physically impossible to muscle in with the second camera, the “Old Pros,” as the CinemaScope crew dubbed themselves, would get their shot then back out quickly with the cheerful call for the widescreen boys, “Time for Beany!”

This happy spirit of competition and camaraderie that prevailed at all times during production of Seven Brides for Seven Brothers is to me convincing proof of the theory that the easiest and most efficient method of working on a sound stage is to harness the collective intelligence of everyone on the stage, blend it, and channel it into one stream. That is the kind of teamwork we had on this picture, with everybody — grips, electricians, props, and others — all apparently inspired by the rollicking spirit of the story.

Folsey’s other credits include Meet Me in St. Louis, Gentlemen of the Press, the Marx Brothers comedies The Cocoanuts and Animal Crackers, and Forbidden Planet.

He was the first recipient of the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award, presented in 1988.

A member of the ASC since 1927, Folsey served as Society president in 1956-’57. After he retired in 1976 with 162 screen credits to his name, he went on to lecture at the American Film Institute. He died on Nov. 1, 1988, in Santa Monica, Calif., just eight months after

being honored by the ASC.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.