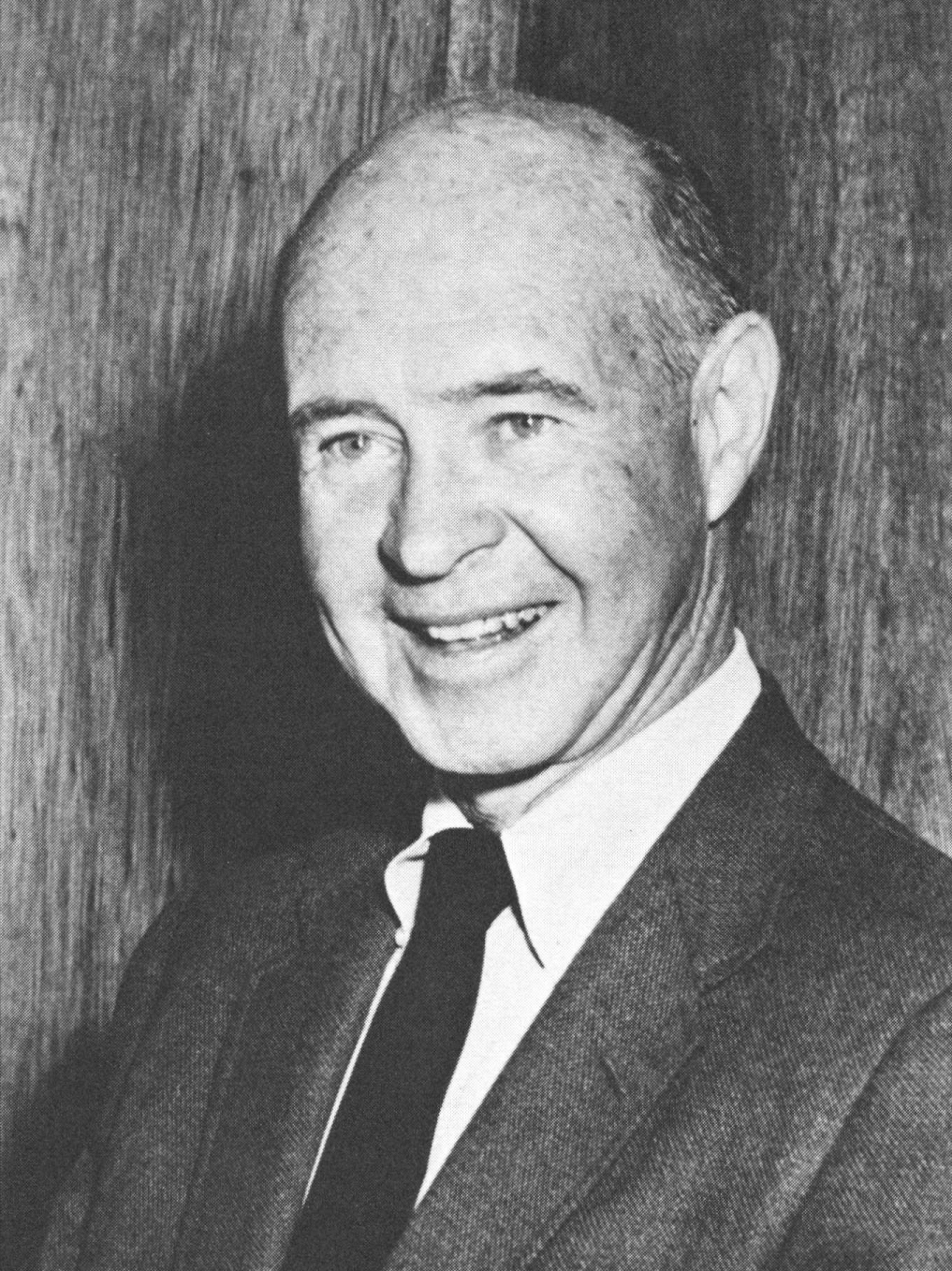

Folsey Given First ASC Lifetime Achievement Award

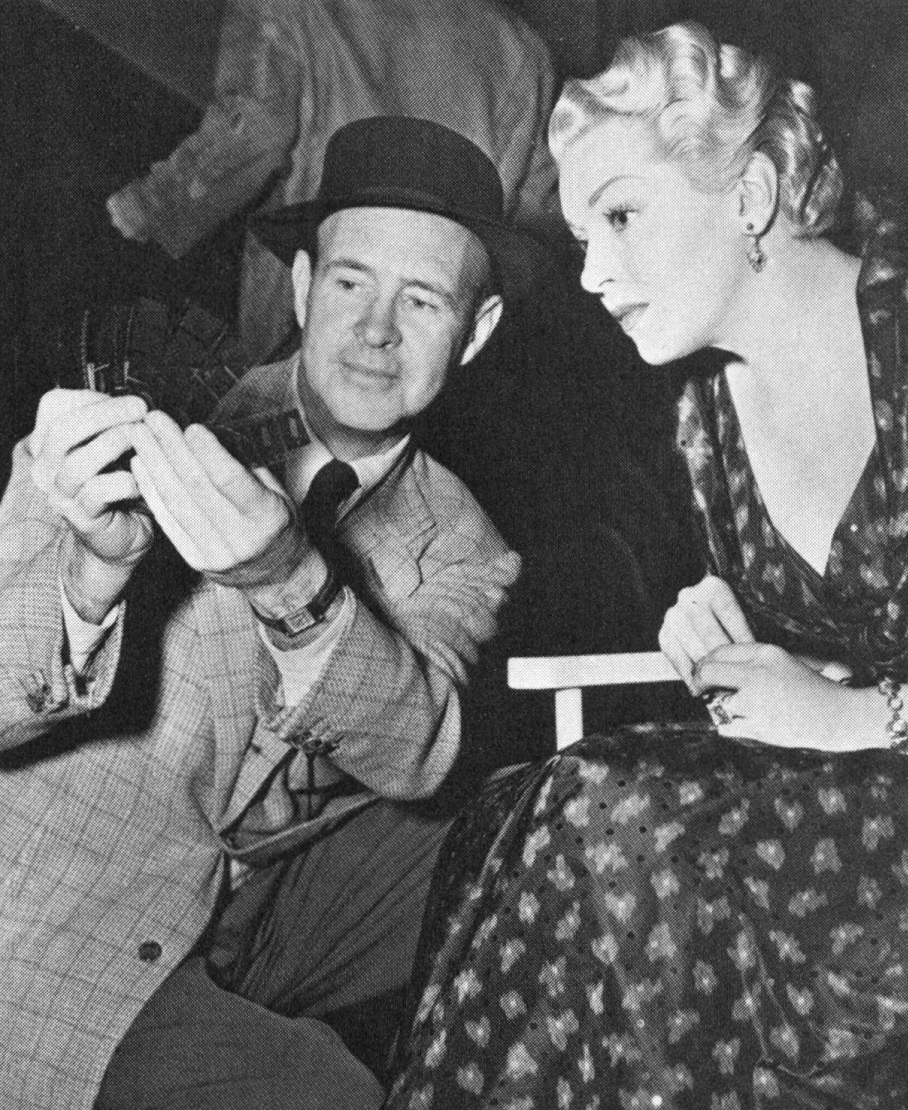

One of the true pioneers of cinematography, George Folsey, ASC earned a reputation as an innovator of photographic techniques.

This profile was originally published in AC April 1988.

George Folsey, ASC, is the recipient of the first Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Society of Cinematographers. The presentation was made on March 6 at the Second Annual ASC Awards Banquet for Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography, held at Universal Studios' Alfred Hitchcock Theater.

"George deserves this recognition," said ASC president Harry L. Wolf. "His body of work speaks for itself. Nevertheless, this was a difficult decision for our selection committee because there are many other outstanding individuals who have also made significant contributions to the art of cinematography. His work was original. There are things that he did with lighting that are still being emulated today"

Folsey's motion picture career spanned 62 years, beginning in New York in 1914, when he went to work as a messenger for the Famous Players Studios. He was the director of photography of some 160 feature films and received an astonishing 13 Oscar nominations. One of his rare ventures into TV won him an Emmy

"During the period when Folsey was winning all of these nominations, Hollywood was producing 500 to 600 feature films a year," Wolf noted. "There were many other great cinematographers working during that time, so it was an extraordinary achievement."

A comprehensive story of Folsey's career appeared in the July 1985 issue of American Cinematographer.

Cinemasters: George Folsey, ASC

By Marc Wanamaker

Editor’s note: This article was compiled over several years of conversations. Wanamaker had initially interviewed Fosley for a documentary he was producing on the studio system of Hollywood.

It’s hard to believe that George Folsey’s career spans from 1914 to 1976, when he was brought back to photograph Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly for That's Entertainment II. He had previously photographed several important pictures at MGM, and it was only natural for him to be the one to do the photography.

Folsey was nominated for more than 12 Academy Awards over the years, beginning with a picture entitled Reunion In Vienna in 1932. His other nominations include The White Cliffs of Dover, Meet Me in St. Louis, Green Dolphin Street, Million Dollar Mermaid, All The Brothers Were Valiant, Executive Suite, Seven Brides For Seven Brothers, and The Balcony. He has been written about as one of the “trendsetters” in the gradual switch from harsh contrast photography to the subtler, more softly lighted black and white photography. However, he was a pioneer in many techniques of cinematography as far back as 1920.

Born in 1898, Folsey entered films at the age of 14, at the Famous Players Company in New York City. He began as an office boy and soon felt that the film business was for him.

“It was interesting,” Folsey says. “I didn’t go to high school; I went right to work. Things were tough in 1914 and a job with such a company was hard to get. In about two years, when I was about 16 years of age, I became an assistant cameraman.”

It was under the direction of H. Lyman Broening that Folsey learned what was needed to be a cameraman. There were several cameramen at the studio at that time, the most important one being Edwin S. Porter. The famous director and film pioneer was a part owner of the company, sole producer of his films, and also headed the camera department. When he came back from a long location shoot, he asked for an assistant. Folsey thought that he could get the job, but it was given to another boy. Emmett Williams, a director who was on location at that time, also asked for an assistant to help with the still photography. This time Folsey was given the job. He learned about still photography and how to load and unload the film holders. He almost became Williams’ assistant, but the director was called to the West Coast and he lost out again.

About this time, Lyman Broening saw that others were getting assistants, so he too asked for one — and he asked specifically for Folsey. Broening taught him well, and he learned how to load and unload motion picture film magazines, how to do special effects within the camera, and other techniques that would help him secure a career in the near future.

“I began as an assistant to H. Lyman Broening, ASC and would count each turn of the camera crank and keep a log of the frames,” Folsey recalls. “This had to be carefully done. After every scene that required double exposures, I would organize this data in two log books as well as on each film can. I had all these numbers to catch and I had to be sure I didn’t make any mistakes, because if there was — if it was wrong, they’d have to shoot it all over again. These numbers were important for shooting the special effects in the camera. This applied to even simple dissolves. It amazes me now to think of the trust they put in a 16-year-old’s hands.”

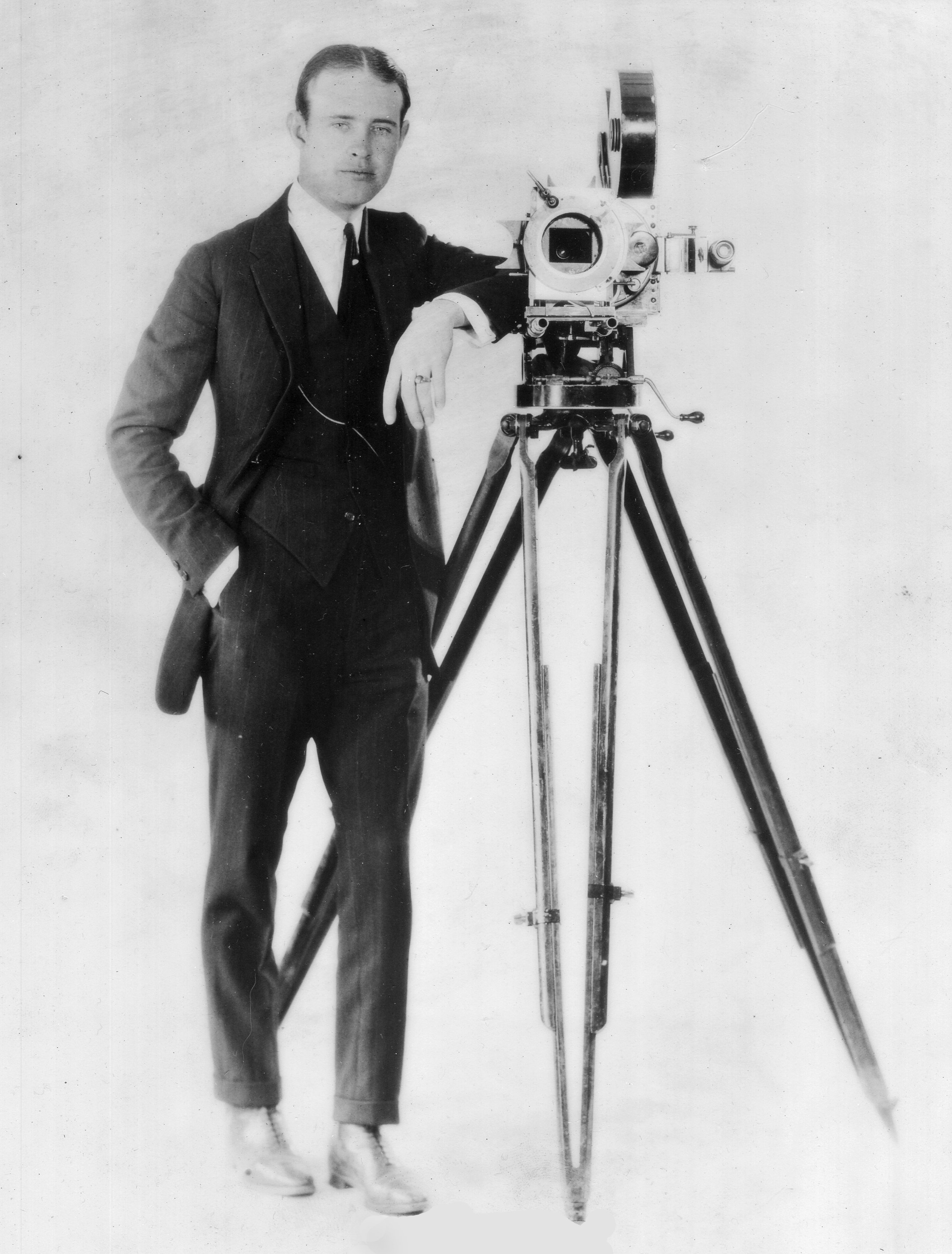

Folsey became an assistant cameraman. His job was to slate every scene, keep track of the footage, load and unload the film magazines and carry the camera and set it up time and time again. They were using the Pathé cameras at the Famous Players Company, and he became very familiar with their use. Under the tutelage of Broening, he did many optical effects within his camera. But it was a few years later that he got the break he was preparing for. When he was 19 years of age, he was given the job of cranking the camera for a foreign negative that would be sent abroad for printing. He was now known as a “second cameraman.”

“We would use a second camera to take a negative of the scene that would later be sent to Europe for printing. This was done to save the shipping cost of prints. I ground this camera next to a French cameraman. He had a long mustache and always wore a Sherlock Holmes hat and a long checkered coat. One day he said suddenly: ‘I quit! I go back to France and raise violets!’ I didn’t understand then that he was homesick for his family. The director, Kenneth Webb, said to me: ‘Can you shoot the picture?’ I said: ‘I can move the studio if you want it!’”

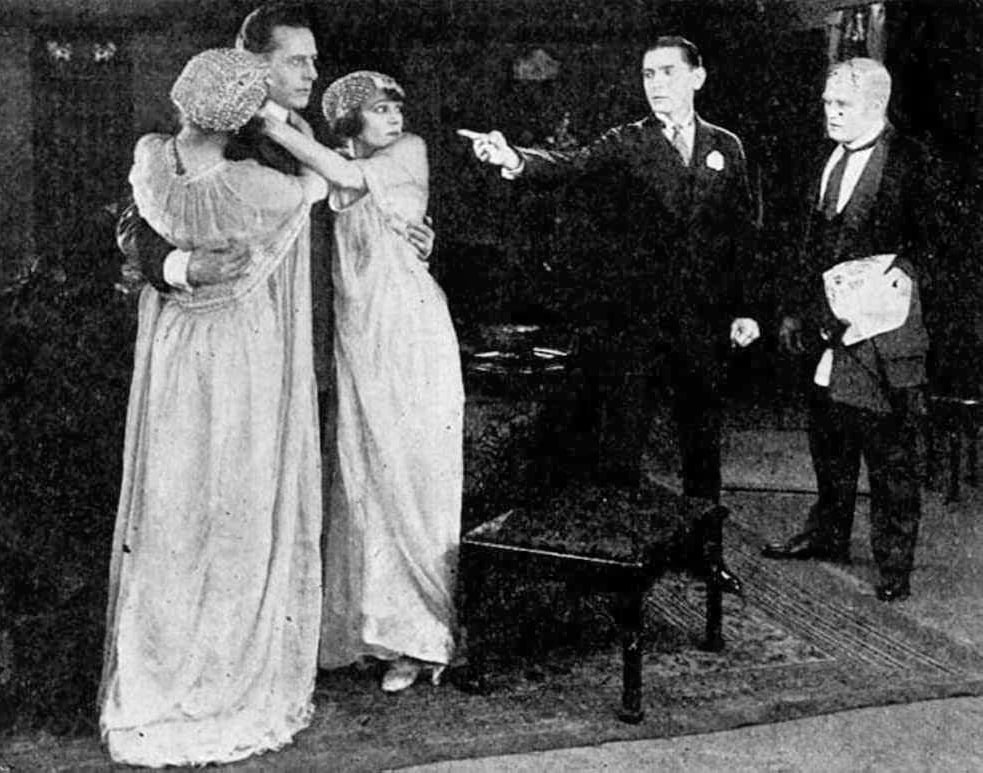

The first picture Folsey began to photograph was called His Bridal Night, starring Alice Brady. He had to shoot double exposures in the camera for Miss Brady’s double role, playing herself and her sister, but his training stood him in good stead.

“That was my first picture, and Kenneth Webb, the director, had to convince Alice Brady that I could do the job,” Folsey remembered. “She was concerned that I was too young. He assured her that if I didn’t work out, he would immediately replace me. She decided to give me a chance, and that was the beginning. It was easy after that, due to the fact that she was in love with the leading man, and it wasn’t hard to capture that on film. You couldn’t photograph her badly; she looked lovely. In about a week, after seeing my work, she offered me a personal contract to photograph her future pictures.”

Folsey finally made it as a full-fledged cameraman at the ripe old age of 19. During the next few years, he became a freelance cameraman, signing a contract with Associated First National and photographing a few Richard Barthelmess films. The most important of these was The Bright Shawl in 1923, with Mary Astor as the co-star.

“Mary Astor was so beautiful; she looked like a piece of Dresden China. We went to Cuba for this film and I can say one thing; I had the greatest time of my life, due to the fact that I had never been out of the country before.”

In the early 1920s, Folsey learned all the technical aspects of his job. There were no light meters and no lighting directors. Folsey said of this situation that you simply had to do everything yourself. The cameramen of that day did not always shoot tests of their films, they just shot what was required the first time. “It sounds risky now, not shooting tests, but we did it and that was that. The film of course had great latitude, it was slow, and reliable.”

During the 1930s, he developed his soft lighting techniques. He was experimenting with bounce light, years before it became the vogue. He was interested in trying to light his subjects in films like the famous painters lit subjects for their paintings.

“From the time I became a cameraman, I thought, how the hell could I get my film to look like the famous paintings of the old master artists I saw in the museums? My first experience came when I saw old master artists at the museums using light for all kinds of effects. From that time on I had it in my mind to photograph my subjects with that in mind. I was an ambitious kid, and wanted my scenes to look better than usual. I had trouble figuring this out and went on my own time to art school to learn more about photography.’

In 1924, he did the photography for The Enchanted Cottage. John S. Robertson was the director and it starred Richard Barthelmess and May McAvoy. The story was of two people with physical deformities who fall in love and move to a cottage in the forest. Barthelmess plays a wounded soldier and May McAvoy plays a horribly ugly girl. In this cottage strange events take place. One of the effects that had to be photographed was when Richard Barthelmess looks at May and sees a “vision” of a beautiful woman in the haunting moonlight.

“She was wearing make-up that made her look ugly. She had buck teeth, broken nose, and ugly hair. I created the effect of her turning into a beautiful woman by using a still camera alongside the motion picture camera. We made a six-foot fade out with May in her ‘ugly’ make-up. When we faded out on her looking straight at the camera, I told her not to move and I traced out her features with lines on the ground glass of the still camera. I then removed her from the set. She then took off all her make-up and returned to the exact spot in the ground glass. She of course looked lovely. I said, ‘Don’t move!’ and began to crank my camera and faded in with a lap-dissolve. When the director, John Robertson saw this scene, he said, ‘George, this is absolutely wonderful!’ I was about 23 years old at that time. It was a big sensation because she had changed right in front of your eyes, there wasn’t a hair out of place and the audience got a real kick out of it, they didn’t know what I had to do to get the effect, but it didn’t matter, the illusion was there.”

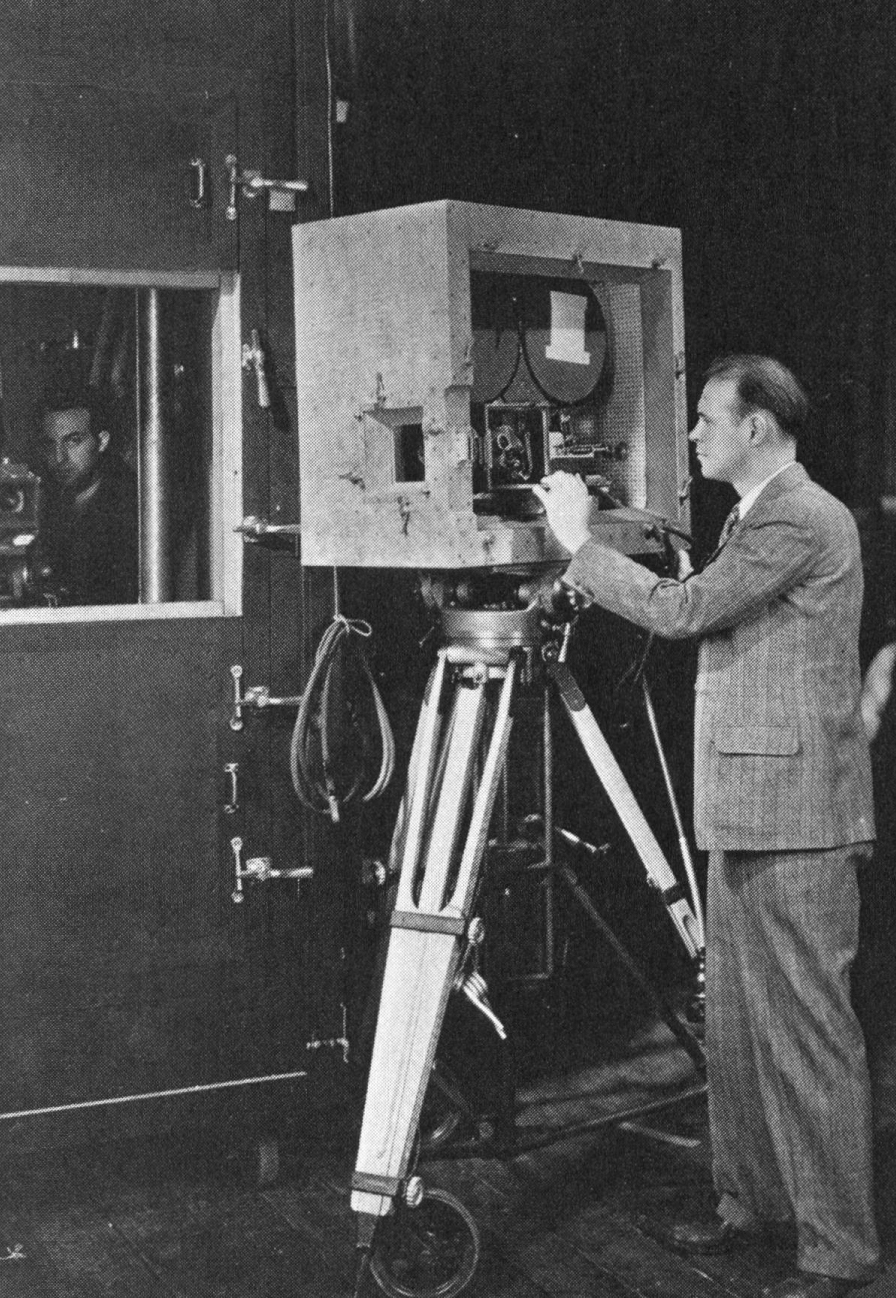

Folsey had been working for First National during this time and they had used mostly Eastern studios. One of the studios he remembers was the famous Biograph Studio at 175th Street in the Bronx New York. They had been leasing the studio for several years until their new studio was built in Los Angeles in the area known as the Barham Ranch. Today, the Western studios of First National are The Burbank Studios. Folsey had been sent West to work on several films. In 1929, on returning from the West Coast after his contract with First National expired, he went to the Paramount Astoria Studios to say hello to his friends and see what was going on there. At this time sound was a new thing and the studios had been gearing up for it. After meeting with some of the production personnel, he was hired to do a picture. But the ‘one’ picture turned into several, all shot at the studio in late 1929-1930. Applause was to be one of his most beautiful films. Directed by Rouben Mamoulian, the film starred Helen Morgan and Joan Peers. The critics of the day said of Folsey’s work, ‘remarkable photography.’ Before he could take stock of what he did, he was on another picture. One of the reasons that he was in such demand at that time was that he knew about the “new” lighting — incandescent lighting. George had picked up the techniques of shooting with such light on the West Coast while with First National. But the main problem was not the lighting, it was sound! At this time the studio had just been equipped with sound apparatus. New problems were created when the camera noises were picked up by the microphones. It was up to Folsey to solve this crisis. On Applause, as well as the other new pictures that he was to photograph, the problem of what to do with the camera, was paramount. Special booths had to be built around the cameras as well as the cameramen. This was complicated with the problem of what to do with the lights, and how to move the booth from scene to scene.

“We had to build a booth around the camera after each set-up. Eventually, we built a booth on wheels and I set the lights on the booth itself to make it easier to move from scene to scene. Joe Ruttenbcrg was my camera operator. We got along just wonderfully. We had no problem at all working together; in fact, I needed all his input, due to the monumental problems we were faced with.”

Finally came the film that Folsey will never forget. It was entitled The Cocoanuts (1929) and it starred the Marx Brothers. The problems he was used to were generally technical. But with the start of filming on Cocoanuts, he was faced with a more unusual problem — keeping the Marx Brothers within his camera range; it was hard to contain them.

“About the Marx Brothers, well, they were crazy!” Folsey explains. “They were remarkably complex people, especially to work with. For one thing, we tried to shoot rehearsals, but this proved to be impossible because the crew would fall down laughing and we could never have silence on the set. So we had rehearsals to get all the mirth out of the crew so that we could finally take a shot. Also, they were very difficult to keep track of. At the end of a scene, they would disappear! It took a team of assistants to find them. On the second picture we did, Animal Crackers [1930], the director placed their portable dressing rooms on the stage and they were watched constantly, like prisoners.”

The Astoria Studio was where Folsey felt at home for several years. He was active there during the years of 1929-’30. He worked there with director Robert Florey on several short three-reelers, one being F. Scott Fitzgerald’s first photoplay, The Pusher in the Face. He was later asked to do more features there, becoming very popular with the directors on the East Coast.

By 1932, he went to MGM Studios to make Reunion in Vienna, for which he received his first Academy Award nomination. He later was the director of photography on Going Hollywood also made at MGM starring Marion Davies and Bing Crosby.

During this time, Folsey’s interest in “bounce light” was developed. At MGM, the head of the laboratory, Jack Nickolaus, increased the speed of the developing machines, resulting in bringing out more contrast in the film. The finished product posed different problems, but Folsey, with his inventiveness created new techniques in the field. He hung large silk sheets and diffusers in front of the lights, creating an effect of soft light. He had to increase the amperage in the lighting to compensate. The results were exceptionally good. Folsey had what he wanted. From the early thirties and into the 1940s, he was known for his bounce-light inventiveness.

Folsey’s career was assured now, and after several years he worked on some of MGM’s more important color pictures, which are now classics in their own right, such as Meet Me in St. Louis. When asked what it was like working with Technicolor, he answered in a most positive way:

“I had been working with the Technicolor Company ’way before my work on Meet Me in St. Louis. There was never a problem in working with them. They didn’t interfere with my work, they just helped me get better results. They advised me on how much light I would need for best exposures. They wanted to have a net under you. We had a lot of respect for each other and they taught me a lot about color film in general. Mrs. Kalmus herself came on the set many times with the colorist to make sure that we all got the best quality in our exposures.”

By 1947, Folsey was shooting another classic film, Green Dolphin Street, for which he was nominated again for an Academy Award. It was for this film that he tried out his most ambitious experiments with reflected light.

“People said that this film was a breakthrough with reflected light. I was interested in bounce light techniques for many years, as you know. But with this film, I had a lot of latitude to work with. I would bounce the light off of big silk sheets placed around the set. They all talked about reflected light being a new thing. I laughed because I had been experimenting with it long before it became a ‘new’ technique. But I put myself on a limb and I’m glad it paid off.”

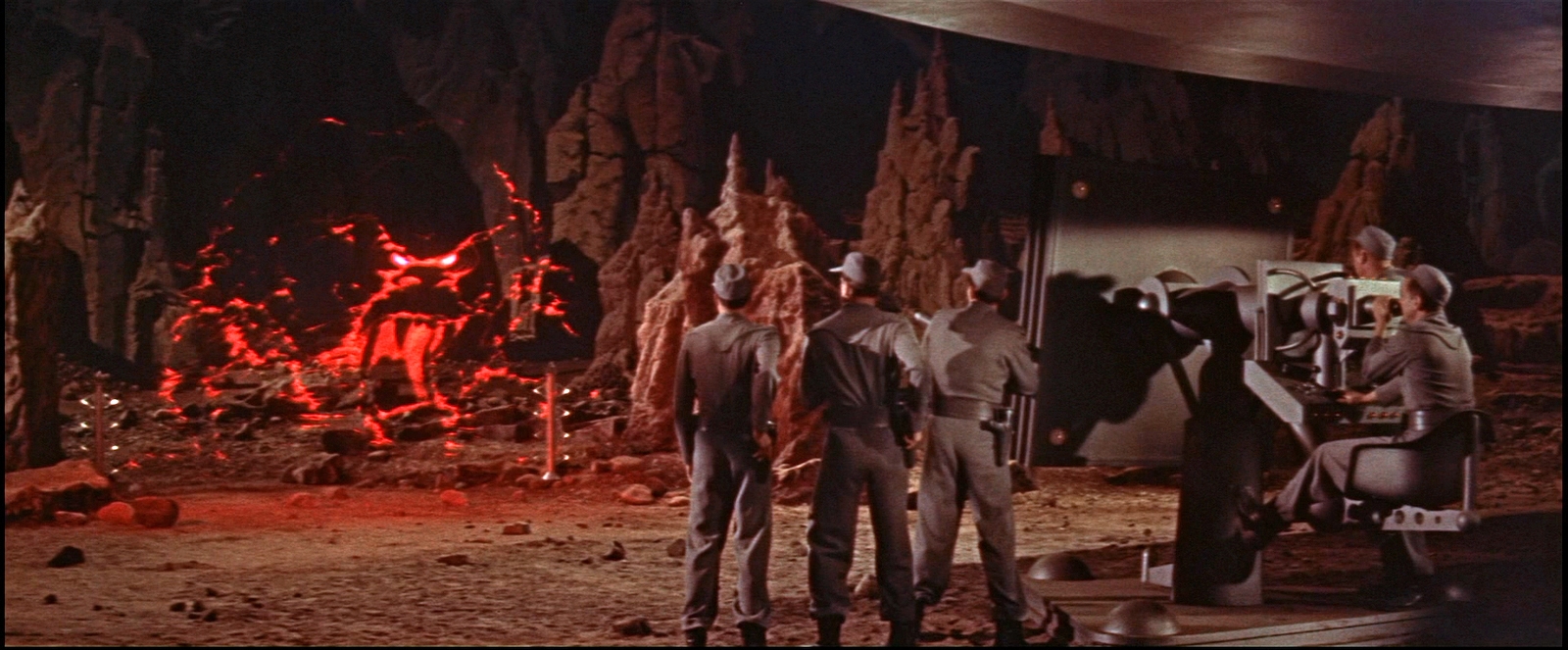

In 1954, he was again nominated for his work on Seven Brides for Seven Brothers at MGM. He was now working not only in color but with Cinemascope. He used two different kinds of CinemaScope cameras on booms to shoot the scenes, saving time and trouble. Then came Forbidden Planet in 1956.

Folsey said that this film was one of the most interesting he ever worked on. It was all shot inside stages and everything was done as he used to do in the old days when special effects were made in the camera. [He wrote an extensive article about shooting the film for AC Aug. 1955.]

In 1963, he was again nominated for his work in The Balcony. Recently, he spoke about the early days when he began in the business: “I had a long career. You know, my family, during those early years wanted me to quit the film business and go into insurance. My parents thought the business of filmmaking would not be steady work for a young man. The funny thing is that I worked almost consistently since I was 14 years of age, until now. I was only out of work for a few weeks at a time during my whole career. It is quite amazing. Over those years I had been to many places, seen many things, and accomplished a great deal. I couldn’t think of any better job for me than what I did all these years. I am also proud of the fact that I tried to get reflected light into films, which gives them an unusual quality. It gives my pictures a brilliance that reminds me of the paintings that I saw in the museums over the years.”

Indeed, George Folsey has given much to the work of the cinematographer. He is a true artist and one of the pioneers of the visual arts. He wanted to discover what the old master painters used to give their works of art a timeless permanence. He succeeded in applying an age-old view of art to that of the film.

In cinematography, as in other fields, experimentation and inventiveness was and still is the backbone of the creative process. Nothing is constant in cinematography; there are no techniques that can’t be further developed. It was people like Folsey, Broening, and all the other pioneers of the camera, that give the newcomers of today a heritage to stand on and a place to continue the great work of the past. George Folsey, for his contributions to the development of the motion picture, will stand among the greats of cinematography in the motion picture industry.

A member of the ASC since 1927, Folsey served as Society president in 1956–’57. After he retired in 1976 with 162 screen credits to his name, he went on to lecture at the American Film Institute. He passed away on Nov. 1, 1988, in Santa Monica, Calif., just eight months after being honored by the ASC.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.

Access the every issue of AC and every story from more than the last 100 years with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.