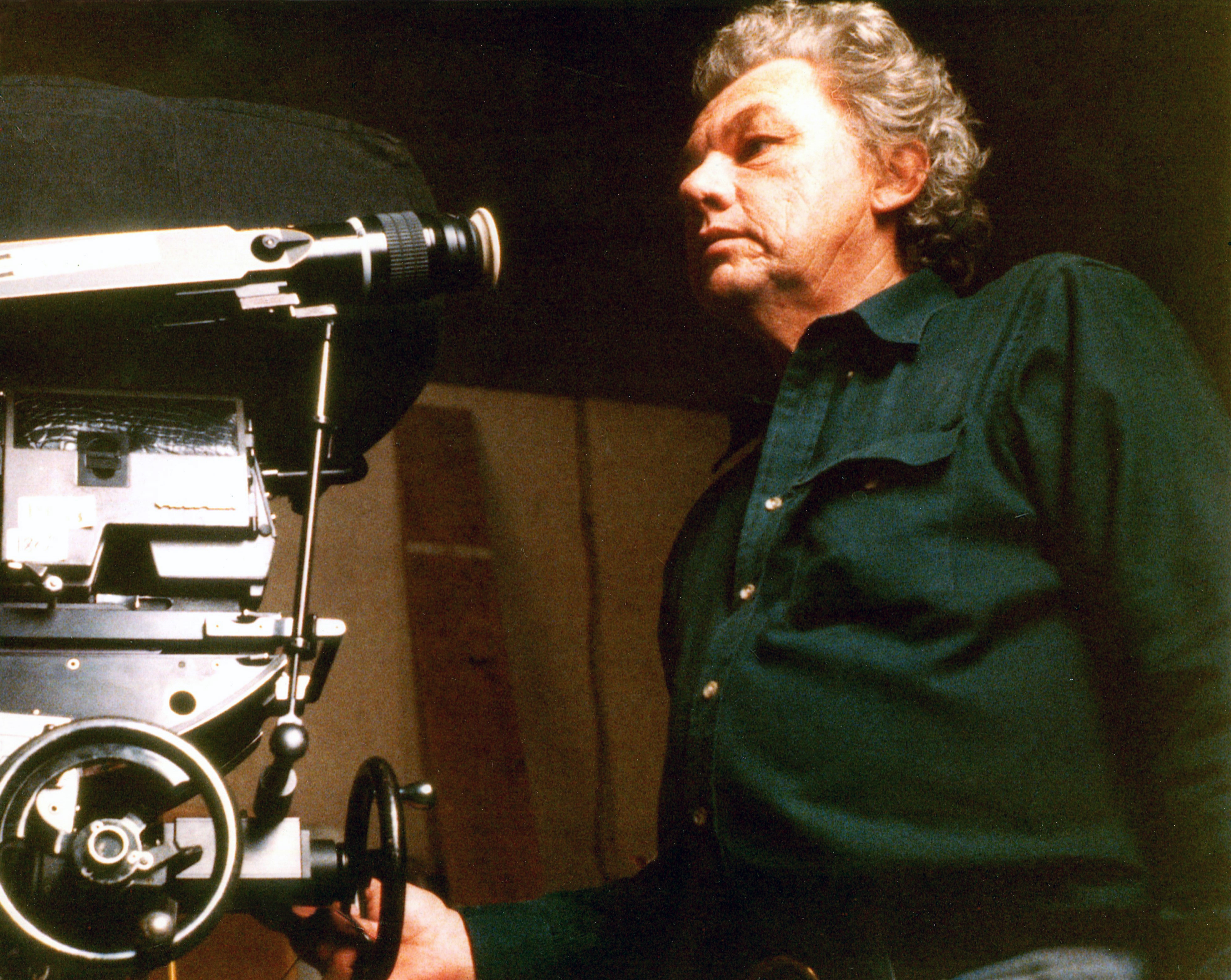

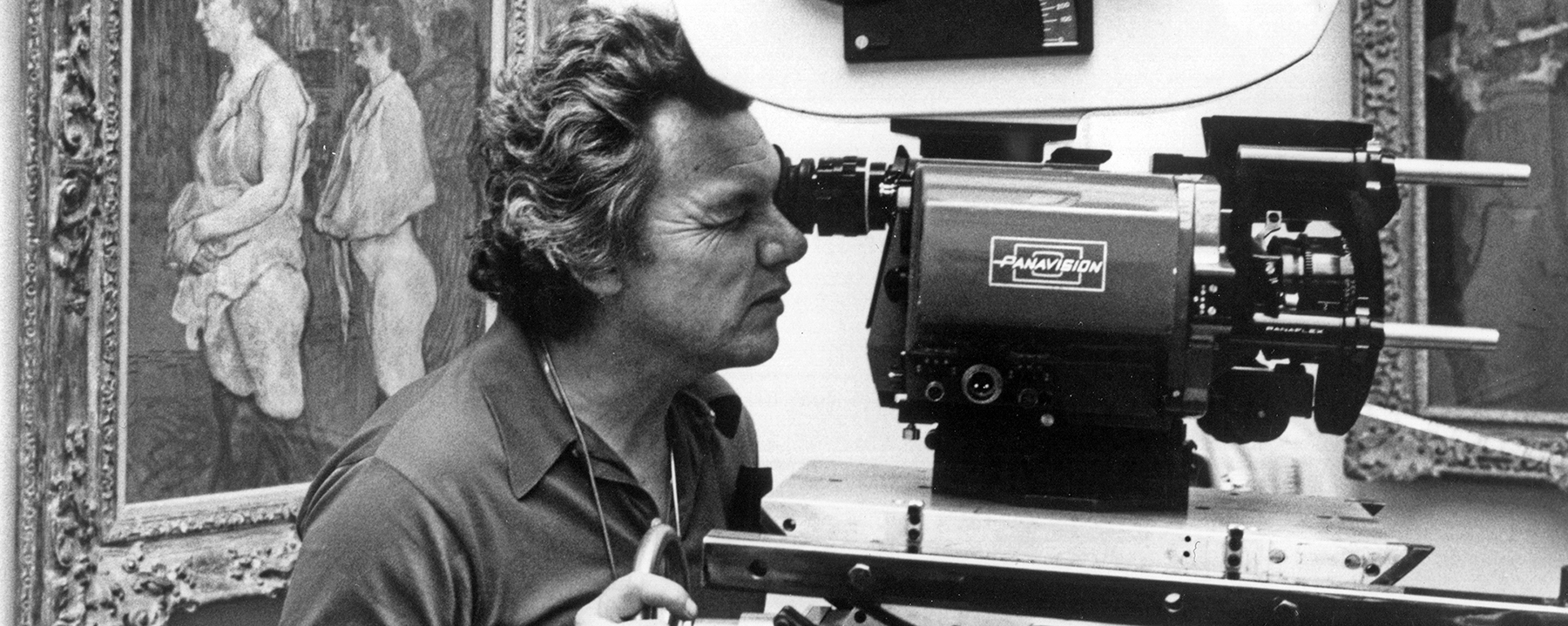

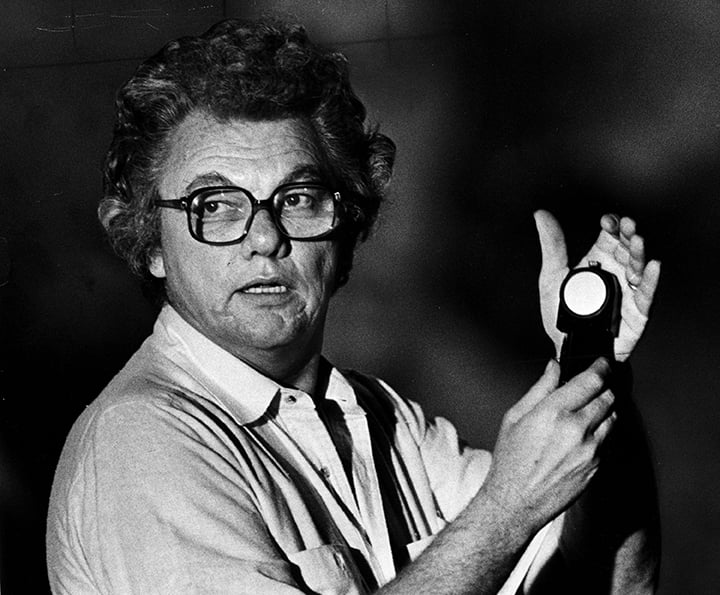

Gordon Willis, ASC Interview at AFI — Part II

In this archival interview, the cinematographer speaks at length about his work and aspects of his creative approach. (Part II of II)

A brilliant, often controversial cinematographer shares his considerable expertise with student filmmakers of the American Film Institute.

This interview was originally published in American Cinematographer, October 1978. (Part II of II)

What follows is the concluding segment of a seminar sponsored by the American Film Institute (West) for Fellows of its Center for Advanced Film Studies.

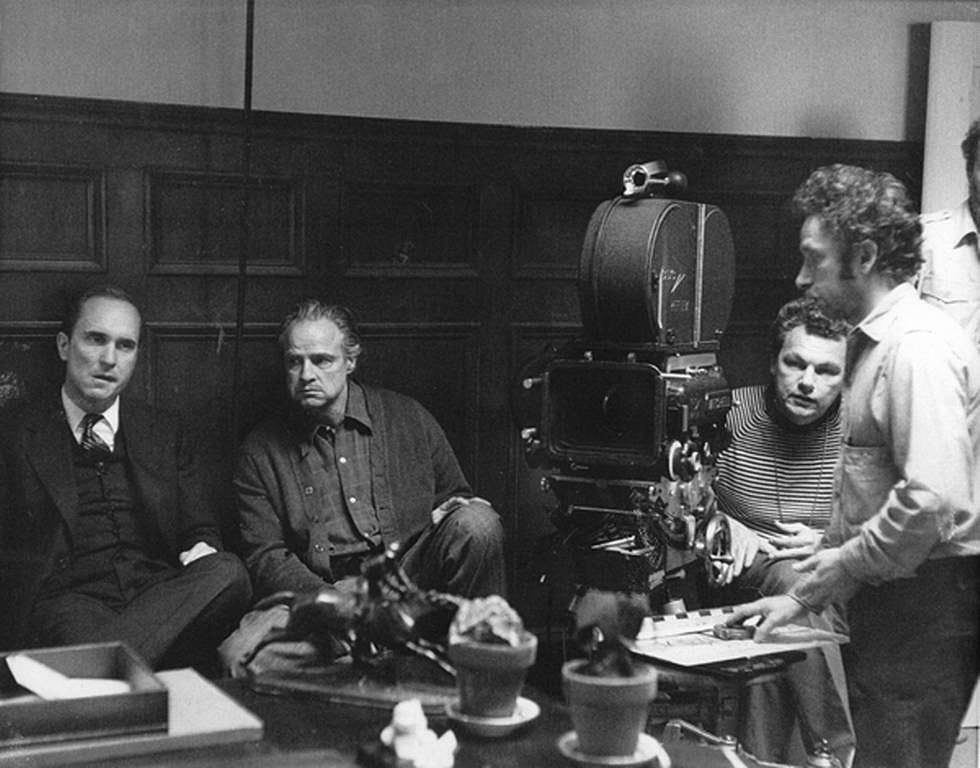

The seminar — moderated by Howard Schwartz, ASC — featured cinematographer Gordon Willis, ASC and was preceded by a screening of The Godfather: Part II, on which he functioned as director of photography.

Howard Schwartz, ASC: Do you have any opinions as to whether you’re more effective with limitations or freedom?

Gordon Willis, ASC: That’s a good question. I have friends who are actors and some of them become confused in making movies because they’re undisciplined. In my opinion, you have a lot of freedom in the movies if you work within the limitations; then you’re free. But I think that you do work better with a certain amount of limitation. There are some things you can’t do if you’re too limited, but the essence of good moviemaking is discipline. There is nothing more horrifying than an undisciplined filmmaker. Things don’t just happen; you’ve got to make them happen. So, yes, I would say that you do function better in a limited environment, because you’re going to use a lot more skill and a lot more brainpower to make it happen. In fact, I’ve probably done some of my best work photographically in a bad situation. I wouldn’t want to shoot my way out of it again, or even get involved in it, but you learn a lot. If you have everything at your disposal, it can get raunchy. Like having too much time to rehearse, or having too much of this, or too much of that. You’ve got to face up to the fact that eventually you’ve got to shoot, and this is it. What I said about actors — any good actor who works in movies for any length of time realizes that he’s going to get the best of himself or herself on the screen by working within the structure of the frame. He can act in the corner, and he can act between his legs, and he can act anywhere, but if he’s not acting relative to what you’re all there for — which is the camera — he’s wasting his time. Good motion picture actors understand that limitation and know how to act within it, as do directors and cameramen. You learn to work within limitations. You are limited. It’s true.

“I do like to keep the same [crew] people, for the reason that I don’t have to say as much to them. They already know. I’m exhausted at the end of a movie. I mean, it’s a campaign for me, even though I enjoy it.”

Do actors ask you what the framing is so that they’ll know the limitations?

Yes. They want to know where they are in respect to the frame. Brando was very heavy with that, because he would never destroy himself in a performance if you were a mile-and-a-half away. At that distance, it’s a physical performance, a body thing, not an acting thing. So he saves himself until he gets to the closeups. It’s the same with any good acting in the movies, and good directors don’t burn actors out in long shots. Acting in a long shot is a purely physical thing. You get it out of the way and then continue on to something else.

You mentioned the fact that as you and Francis Coppola work more together, you communicated better and the need for dialogue between the two of you became less and less. What about your communication with the people on your crew? Do you keep the same operator, the same gaffer?

I’ve used several operators. I had one operator who did six pictures with me and then it was time for him to go on and start shooting his own pictures. So the answer to your question is, yes, I like to keep the same people, especially gaffers and grips. Grips take a terrible beating on shows that I shoot, much more so than electricians, because they have a lot more to do. But I do like to keep the same people, for the reason that I don’t have to say as much to them. They already know. I’m exhausted at the end of a movie. I mean, it’s a campaign for me, even though I enjoy it. Mostly my head is always going on a concept level, not simply a photographic level. As I said, photography comes out of a concept. If I get hung up on a set, it’s because the concept is no good. There’s no direction. We don’t know which way we’re going.

“I never have a difficult time working with directors. You always try to look for people that you know you can get along with. It’s like choosing the girl you marry.”

Speaking of concept in terms of photography, I noticed in Parallax View that the photography really seemed to change when Warren Beatty became involved with the Parallax Corporation. The shots seemed to change compositionally; they took on a different look. Was that something that was planned, or did it come out of the locations?

For the most part, such things are planned. It’s like picking focal lengths to shoot with. There are a lot of machine-gun shooters in the business right now, which is a shame. They just arbitrarily cut close-ups with a zoom lens. For example, let’s suppose I shoot a close-up of an actor at 150mm. Then I turn around to shoot the matching close-up of another actor, only to find that, because of the physical limits of the location, I can’t get far enough away to shoot him at 150mm. I end up shooting his close-up at 50mm – and you’re forced to do that occasionally – but I’ll do anything to avoid it, because when you cut those two close-ups together the backgrounds won’t match, the perspectives won’t match, and the feeling won’t be the same.

Do you have a more difficult time working with the directors because you do have a very strong opinion, rather than simply saying, “I’m going to photograph the film”? Does that make it kind of harder in a way?

I never have a difficult time working with directors. You always try to look for people that you know you can get along with. It’s like choosing the girl you marry. There are some directors who wouldn’t touch me with a 10-foot pole. But there are others that I work with and have a wonderful time with. Directors have a difficult time shooting a movie. It’s a horrendous experience. They’re getting beaten to death by the company; they’re getting beaten to death by actors who don’t want to cooperate; they’re getting beaten to death by everyone. The mere fact that a director stays on his feet for 8 or 10 weeks, or sometimes many months, is a miracle. So I’m a director’s cameraman. I would not take a job via a producer, because I feel that when you make a movie, you’ve got to have a united front. Aesthetically, physically, you’re taking on a whole group of people. I don’t get along with all directors, but that’s a personality thing that everybody has to cope with.

Speaking of that, would you like to get into directing?

Not really. I’m actually better as an improver; that’s what I am. I’m better at working out concepts with directors. With me, a director can feel very secure if he has an idea about a movie, because when he’s tired, I haven’t forgotten the idea. And when I’m tired, I expect the same thing from him.

“It’s very easy to set a camera when you know what it is you’re trying to do. It goes all the way from the philosophy to where you’re standing at the finder and you’ve got to put down the shot.”

In that same director, could you talk a little more about what you expect from a director?

I have to know from him what it is we’re doing with the movie — what is the basis of the movie. This comes out of philosophical discussions and it’s the most important part, in my opinion. I never walk into a room and ask him, “How do you want me to light this room?” You can light it 50 different ways, depending on what it is you have to accomplish. So what’s important to me, that has to come from the director, is: “What is the movie about? What is it you want to say, and how do you feel like saying it?” Then it boils down to: “How do we handle these things?” After that, you go out and start doing it and that goes on from day to day. But once you have the philosophy of the movie set, you’re no longer vulnerable. Your working decisions can be made from day to day, minute to minute, because you know what it is you’re trying to do, or what you’re trying to say. Sometimes the script’s being turned upside-down and nobody is really sure what it is they’re trying to do — what’s the scene’s about, what the picture’s about. But it’s very easy to set a camera when you know what it is you’re trying to do. It goes all the way from the philosophy to where you’re standing at the finder and you’ve got to put down the shot. But it’s based on the philosophy.

Do you think such discussions help to avoid the question of who’s picking the set-up?

Yes, because you’re working together. Some directors like to lay out shots. Other directors give you the shot. It depends on who you’re working with.

In reference to that, could you explain how you worked with Coppola in blocking out each shot for Godfather II?

Well, it was much easier the second time, because we had become nicer to each other. But, especially at the beginning of shooting, Francis would spend a great deal of time laying out the way he wanted sequences to play. And he had very definite ideas about how they should be structured. So you’d end up with 10 cuts in a sequence that you’d know about in advance. He’d lay them out and we’d go over them together. When things are thought out that well, they go much more smoothly.

“You can tell when a director’s having problems. He stays too long in the corner with the coffee.”

It’s great that Coppola could give you 10 cuts from the beginning of a sequence. It’s beautiful when a director can do that, because then you can plan your lighting so that you don’t trap yourself. That’s the problem with directors who can only tell you about one shot at a time. You establish lighting, and now what do you do on the next cut? It’s in the way and you’ve really got problems. Now you’ve got to hang lights from trapezes and do all sorts of other things to match your breaks. It’s a luxury when a director can give you 10 shots in advance.

If he gives you the set-up and tells you what he’s going to do, it’s terrific.

When he blocks things out for the set-up, does he include camera moves at specific points? In other words, does he do or do you do it?

Sometimes it’s him, sometimes it’s me; sometimes we work it out together. It all depends.

But he has a strong idea to begin with?

Oh, sure. Sometimes you don’t have any strong ideas. I mean, you have the philosophy, but you have to sort of develop the structure as you go along. You can tell when a director’s having problems. He stays too long in the corner with the coffee. If he gives you 10 shots as I said, and you get through two of them, and then he’s too long in the corner with the coffee, you realize you’re about to make another five cuts, or maybe you’re adding one, because it’s not working. If a director’s a good cutter, he can see it coming — which is great, because I hate to see it coming at the end of the day when there’s no way to solve it, generally, except to start over.

When a director lays out the 10 shots for you, I take it that those are specific shots and it’s not sort of, “Okay, let’s cover the scene.”

It ranges from specific shots to “Let’s cover the scene.” But if you know a director well, you know what he means when he says, “This is what I’m going to do here: I get a shot of him, I get a shot of her, and I get a shot of the cat.” He doesn’t have to draw a picture beyond that, because you know the story and you know it has to be done in a given way.

But when [director] Jim Bridges was here, he talked about the fact that no matter where you put the camera, or what the shot was going to be, he would actually run the scene all the way through for the actors. It seems to me that in doing that, you’re never really sure how you’re going to cut the scene together.

You’re talking about The Paper Chase — which is a good movie, in my opinion. It’s a simple movie, and I liked it. But what Jimmy was actually saying, I think, was that for the actor’s benefit, for the sake of the performance, he was letting it go all the way through. Some actors need that, some don’t. You may only be doing a close-up of one actor, and he may have only one or two lines, but you’re playing the whole thing to get him up to where he’s supposed to be.

“There’s more old junky equipment sitting on studio lots than you can imagine. When you do a studio picture, they’re always trying to get you to use their junk that has been sitting there since 1908; it’s ridiculous.”

Did I understand you to say that you took stills before The Godfather started in order to get your color right?

No, no. The very most I do is run a test for the laboratory just before I shoot simply to get the printing light. I don’t do anything else.

But did you show this to Francis? Did he know what he was getting?

No, because on The Godfather he was having a lot of problems. He really didn’t have time for that. I was very happy that the movie developed into what it did, because it was very difficult to shoot. It was hard for him because he was under attack.

Could you talk a little bit about the rhythm that takes place on a set when you’re shooting that has to do with camera rehearsals, the time you need to light, and when you light, if it all unfolds ideally?

Well, the director gets the set, works out his problems with the actors, and stages the material the way he’d like to have it run. There are directors who push actors around within a given frame during rehearsal, but for the most part, you’ll find them working it out with the actors so that the scene falls into place and plays well in the room from the point of view that he wants to photograph it. Once that’s done, and the actors are comfortable, then you come in and set up a finder, and you start cutting it up as to how he’d like to cover it. Then the actors go away, the stand-ins come in, and you light. That’s the right way to do it. Now, a lot of times a director will say, “They’re going to be over here in a corner and he’s going to be reading a book.” Well, that goes over like a lead balloon with me, because they’ll go away and rehearse and change the blocking, and the result is that he’s not in a corner reading a book anymore; he’s over at the refrigerator. So what you’ve done is a lot of lighting for a set-up that is irrelevant. It’s best that they work out all the problems in blocking on the set, because you’re not saving any time by doing it twice. So rehearse, block, go away and rehearse on a verbal level, then come back and we’re ready — we shoot. It goes much faster that way.

Could you tell us a little more about how you control diffused light?

I used to bounce light, and I’ll still do that for quickie shots. But what I do now — and I’ve got it down to a fairly good system — is just use 4 x 4 diffusers. There are two of them, actually. One’s the frame and the other’s the frame with the diffuser on it. We have various methods of using them in a room. Usually the grips will put them right into the ceiling. The second diffuser, which is hanging from that particular frame, is 14 to 20 inches from the bulbs, which are in the first frame. All four sides of that are black fabric, which is rolled up. Now, let’s say, for one in the middle of the room, you’d just chop the walls by letting the fabric down. Of course, the higher it is, the less you have to fool with it because of actors walking under it. But when you have actors who are getting too much light in a certain position, you can just slip nets under the top of it.

“I hate scripts that say, ‘You move into that and you cut here.’ Because, first of all, that makes it hard to read and, secondly, nobody cares.”

Are the bulbs pointed directly down?

No. Usually you have them going sideways.

When you speak of a 4x4 diffuser, is that a standard lighting fixture?

No. It’s one that I made. I made up a whole series of the frames. I used to use silk in them a long time ago, but it’s not as effective. It’s also too expensive and you can’t get it anymore. So, like the rest of the world, I’ve gone to plastic — which is cheaper. I use a material that I had Rosco make. I call it “shower curtain.” It comes in two densities. They came in and showed me the full density, which was very thick. I said, “That’s great. Make some half that thick.” So they made two densities, and it’s terrific stuff.

When you have an idea for something like the “shower curtain” or a special kind of frame or a light that’s named after you, do you go to a company that you like and say, “I’d like you to make this”? Do they give you a free supply for the rest of your life — or how does it work?

I’ve never gotten a free supply of anything — and I don’t want it. But, no, you sort of cooperate with each other, so to speak, in the business — because you’re doing them a service and, in return, they’re doing you a service by manufacturing the idea. So just making it available is a service. The hard part is to get somebody to do something new.

Then, does that become your invention, or is it just a contribution that you’ve made to the industry?

You owe it — I think you owe it. This business has been very good to me. The people in it have been very good to me. I think you owe it to the business to teach people whatever it is that you know — if it’s worth anything — and to contribute whatever makes it easier. Movies are very expensive, so whatever you can do to move things along or make production more efficient is worthwhile. I mean, there are many camera manufacturers around who are using ideas that I gave them, but those ideas help other people because they make for a more efficient, more systematic way to work. So, to go in and say, “I’ve got an idea,” but then stick them up is a total waste of time. You get nothing out of it.

This is the only major industry that doesn’t have a facility for conducting research on a regular basis. The research comes from guys like Ed DiGiulio [the founder of Cinema Products], who’s in the business of manufacturing cameras. He gets his ideas from Gordon and other cameramen and this is how progress is made. But it’s not through the studios having any kind of research organization.

There’s more old junky equipment sitting on studio lots than you can imagine. When you do a studio picture, they’re always trying to get you to use their junk that has been sitting there since 1908; it’s ridiculous. It’s all pig iron; it weighs a ton; and it’s unusable, really — at least for me. It’s not contemporary material and I can’t work with it. They ought to take it out to sea and dump it.

“I’m what they call a two-time reader. When someone’s good enough to send me a script, I’ll read the first 12 pages and, if it’s no good, I won’t read the rest of it.”

I understand that you did not have a detailed shooting script for Godfather II — a script that spelled out every shot in detail, that is.

No, we didn’t. In fact, I hate scripts that say, “You move into that and you cut here.” Because, first of all, that makes it hard to read and, secondly, nobody cares. The fact is that the director is going to take it and shoot it the way he wants anyway. So, no — there’s only things like: “Cut to interior, day.”

And you don’t feel that takes any longer than if it was spelled out?

No. Sometimes you get directors who are writers, but otherwise it’s very difficult to predetermine the shot. You can predetermine a concept when you’re writing, but a shot you can’t. And it clutters the script. In fact, by the time the film’s cast and everybody’s together, the whole thing is changed anyway.

Do you think that Francis Coppola changed the concept of the film at all as it was being shot?

A little bit — because, as directors work, they see that certain things aren’t working. That’s working and this isn’t. And so, they’ll change. But, basically, no. The real changes came in the editing — a six-hour film cut to three hours.

A lot of good work went down the drain.

I don’t even want to think about it.

Does it bother you that a lot of your work will never be seen?

It bothers me. I’m not bothered on a personal level because it won’t be seen. But I hate to shoot that way. You always have to shoot excessive material for a movie in order to give the director and the editor enough to work with — so that scenes play properly, and also because things you think are working when you do them don’t work when you cut the whole thing together. But to shoot double — which is what we did — is horrible. None of us knew what was going to be in the movie. There were no throwaway shots. Everything was hard to do.

Do you think there’s any way it could have been planned economically — so that you could have shot less than double?

Well, as Francis said, if he’s had more time to write, then he could have cut it back.

“You can get hung up on so much technology in shooting a movie that pretty soon you can’t function, because you’ve got so much going on. The simpler the tool and the more effectively you use it, the better you can get things done.”

But doesn’t writing involve planning in his own mind what the shots will be?

Sure. But not the shots — the story content, what he has to say. I always told him he loved shooting 200 pages. That’s a director’s dream — 200 pages. But really, he just didn’t have time to, you know, cut it back.

How do you go about reading scripts and making any kind of decision about them?

Badly. I’m what they call a two-time reader. When someone’s good enough to send me a script, I’ll read the first 12 pages and, if it’s no good, I won’t read the rest of it. Meaning that, after a while, you know whether there’s any taste, any maturity in the idea. It’s very quick. Then you read the end of it and, if it looks good, you read the whole thing. The reason that I read a script twice is that a lot of things I’ve shot I’ve hated when I first read them.

In preparation for shooting on a particular set, do you like to go in ahead and get it in your mind? Or would you kind of like to forget about it until you’re lighting it?

No. I’ll get it in my mind ahead of time, because that saves a lot of time. Especially if it’s an important set, I like to think about it. I may not know then what the set-ups are going to be, but I’ll know how to treat the room, so to speak, and that saves time.

I’m curious to know if you used any post flashing throughout filming of The Godfather?

I’m not a flasher. (Laughter). It works very well for some guys, and to each his own. The reason I’m not is that I don’t believe in introducing anything more into a laboratory than delivering the film and letting them do what I told them to do. I say, “Just do the same thing every day and everything will be cool.” Flashing means handling the film more and more, because they run it through a printer. You can get hung up on so much technology in shooting a movie that pretty soon you can’t function, because you’ve got so much going on. The simpler the tool and the more effectively you use it, the better you can get things done. I don’t believe in flashing. I know what it does — I’ve done it — but I would rather introduce things photographically that I can handle in the camera, whenever possible, because that simplifies it.

“There are actors who act to the floor. They come out of the Lee Strasberg school. It’s good for theater-in-the-round; it’s good for digging ditches; it’s terrible for motion pictures.”

Working with your system of overhead lighting, do you still use Obie lights?

Yes, I use Obies. Howard was kidding me before about not putting any light on the actors, but it’s true. They accuse me of not letting the audience see the actor’s eyes. A lot of times in a scene I’ll shut down on an actor’s eyes; then, at a given point, you begin seeing his eyes. For that purpose, I use Obie lights and I use open bulbs fixed to the front of the camera.

Do you use foamcore the same way, to put a light in someone’s eyes?

Yes, or white card. There are actors who act to the floor. They come out of the Lee Strasberg school. It’s good for theater-in-the-round; it’s good for digging ditches; it’s terrible for motion pictures. I got mad one day at [Al] Pacino and said, “Why don’t we get a glass table and just put the camera under the table? All right?” I mean, there’s a point where you can’t lower the key light anymore. So yes, foamcore or a white card works very well with overhead lighting.

Did Lee Strasberg in Godfather II act down at the floor?

Oh, Lee’s terrific. He’s a nice man. I don’t think he believes half that stuff. He once believed it, I guess, but I think the actors do a lot of numbers on him. He was wonderful. He’s right there.

Do you want to shoot a black-and-white picture?

Yes. I’d love you. I’ve shot a lot of black-and-white, but never on a feature. The problem with black-and-white is that it tends to make statements. Somebody says, “Well, we’ll make it a black-and-white film.” They don’t just shoot the movie in black-and-white. Now it’s become an important “statement” to shoot it that way; whereas, if they’d just go ahead and select it occasionally for a movie, I’d love it. I think black-and-white is great. It doesn’t get in the way of the story. It’s actually a more interpretive medium than color.

“I don’t particularly like having to light actors for ego reasons. To me, it gets in the way of the movie. You can’t imagine how difficult it is to do, because you’ve got a concept for the look of the movie, and at the same time you’re dealing with how a personality is supposed to look.”

Do you still use any bounce light techniques?

Yes, I do. I did a movie with Barbara Streisand [Up the Sandbox] and bounced myself to death. [Laughter] The way I finally licked Barbara’s problem was to have practically all of her key lights coming off the walls. I would key a lot of times by just hanging something onto the wall.

What material do you use for bouncing — space blankets?

No, they’re horrible. White sheets, white cards, white walls. I just have the ceilings painted white on location sets, and use that. It’s less directional, very soft, and it works.

Did Barbara Streisand request that?

No. She’s really wonderful, actually, in many ways, because she feels and knows that she looks good in certain ways. Most of the time she’s right. So your advantage there is that she’ll work with you. If you say, “Don’t do that, do this,” she’ll do it, because it’s to her advantage. She’s interested. She likes to talk about lighting. She had a “left-side, right-side” kind of concept about herself. I said, “Are you going to go through this while moving left-to-right, Barbara? Aren’t you ever going to go right-to-left?” The truth of the matter is that she looks good from both sides, but she thinks she only looks good from one side. Well, if that’s on her mind, that’s on her mind, and you have to deal with it. I don’t particularly like having to light actors for ego reasons. To me, it gets in the way of the movie. You can’t imagine how difficult it is to do, because you’ve got a concept for the look of the movie, and at the same time you’re dealing with how a personality is supposed to look. It’s tricky, because you’ve got to make the movie look like one thing, while making him or her look like another thing within it. But I managed to do it, actually, and it worked out pretty well. It didn’t bother me.

When you bounce light off the white material, do you always use it on a flat surface? The reason I ask is because many still photographers use curved reflectors, umbrella lights and such — but Billy Putman once said that using them generally was a mistake, because a parabolic reflector focuses on the light.

He’s right. When you take a light and flatten it out against a wall, it won’t be as directional as umbrella light, but I like umbrellas sometimes. They’re terrific for certain things.

How about parachutes?

Only for jumping. (Laughter). They get too big.

But they give a nice soft light. They’re used in shooting commercials — why not features?

Because you’ve got actors and hundreds of people walking around and talking — and soundmen. You sort of have to make everything work within the structure that you’re faced with. On the other hand, one man’s thing is another man’s poison — or something. If somebody’s used to working with a certain thing, he should work with that.

With your concern about laboratories, did you have the European footage developed by Technicolor in Europe?

Yes — Technicolor in Rome, for both pictures.

What was your comparison between the labs?

The Italians do very good work — better work, actually — if you can live through the emotional upheaval of getting to them. It has nothing to do with technical things particularly. It has to do with the emotional aspect, but once you solve the emotional problem and they understand what the movie is about, they’re wonderful. They just do lovely work, but you’ve got to go through a thing.

Are you at all concerned about how your photography will look in the drive-ins? Everybody hates them.

The drive-in screens are a lot better than they used to be. You get a lot more illumination in drive-ins now than you used to when the question was first raised. As a matter of fact, I haven’t heard a producer raise this question in years.

So you’re not really concerned about maybe printing up a little bit — requesting lighter prints for the drive-in release?

No, because the truth of the matter is that you’re second-guessing every theater in the United States and all over the world. The question used to be: “What’re they going to do in the drive-ins?” Well, a lot of drive-ins are still sub-standard in projection, but so are a lot of hard-top theaters. All of them should have to conform to a certain standard of quality. They should have police doing it — running around fixing up theaters. [Laughter].

Gordon, thank you very much for a most interesting discussion.

You’ll find Part I of this interview here.