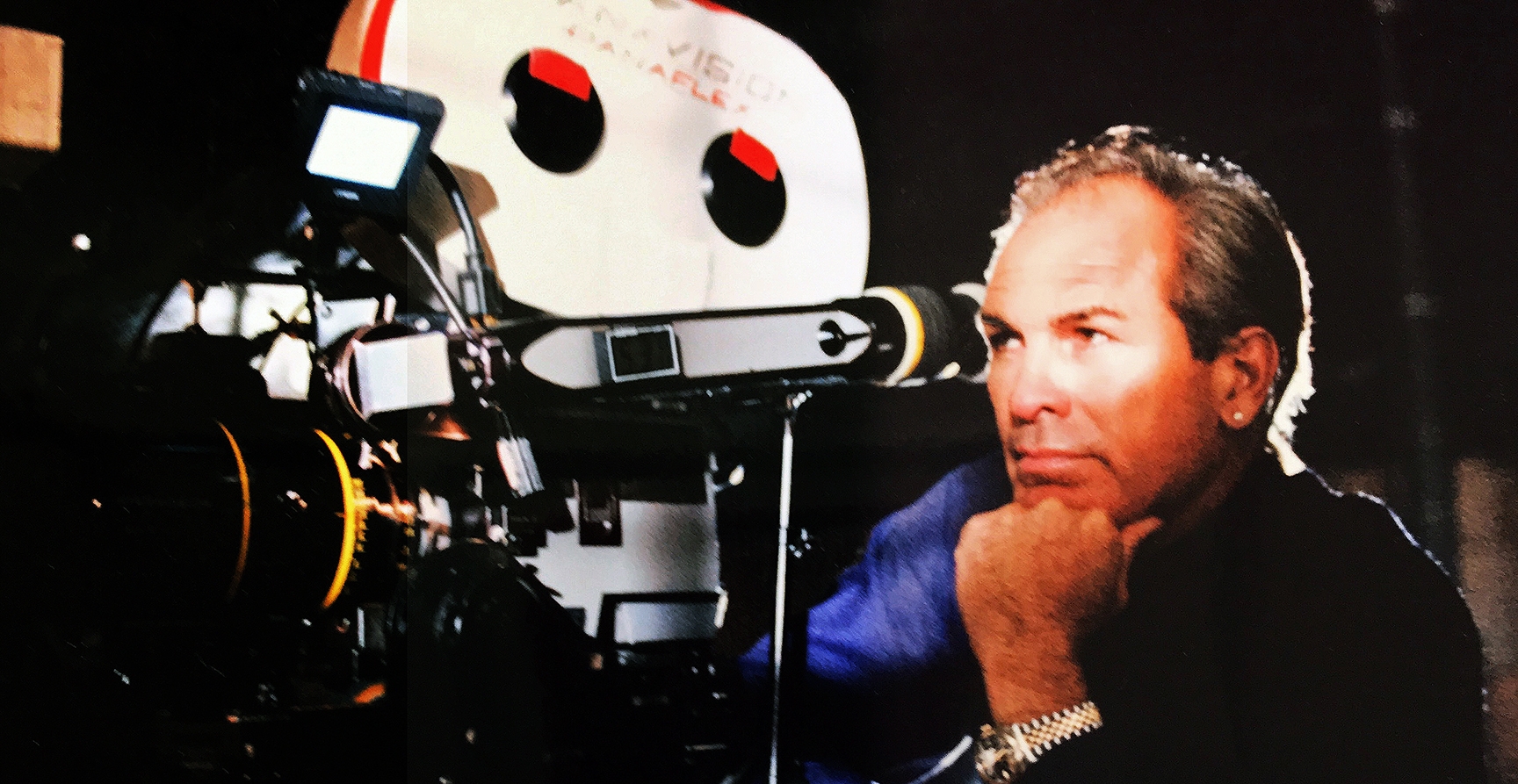

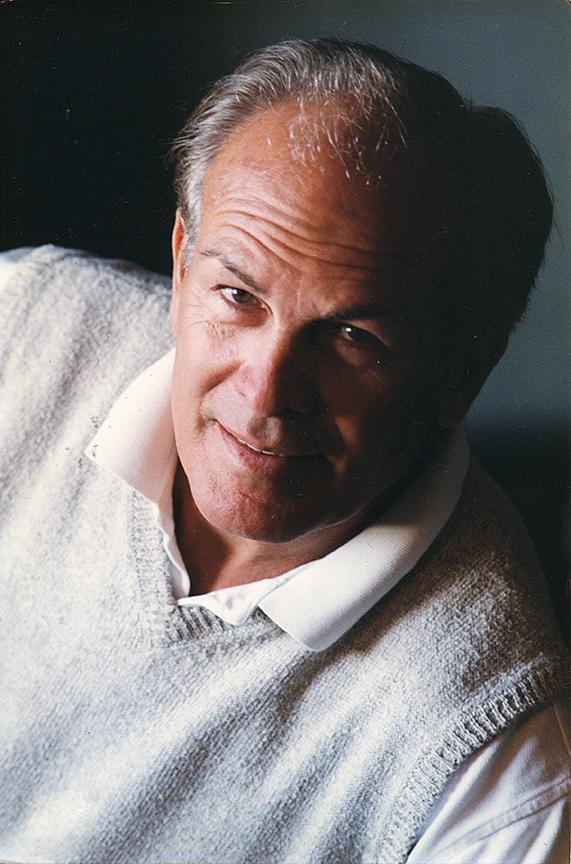

ASC Close-Up: Steven Shaw — Extended Cut

In this edition version of his ASC Close-Up profile, the cinematographer details his extraordinary life behind the camera.

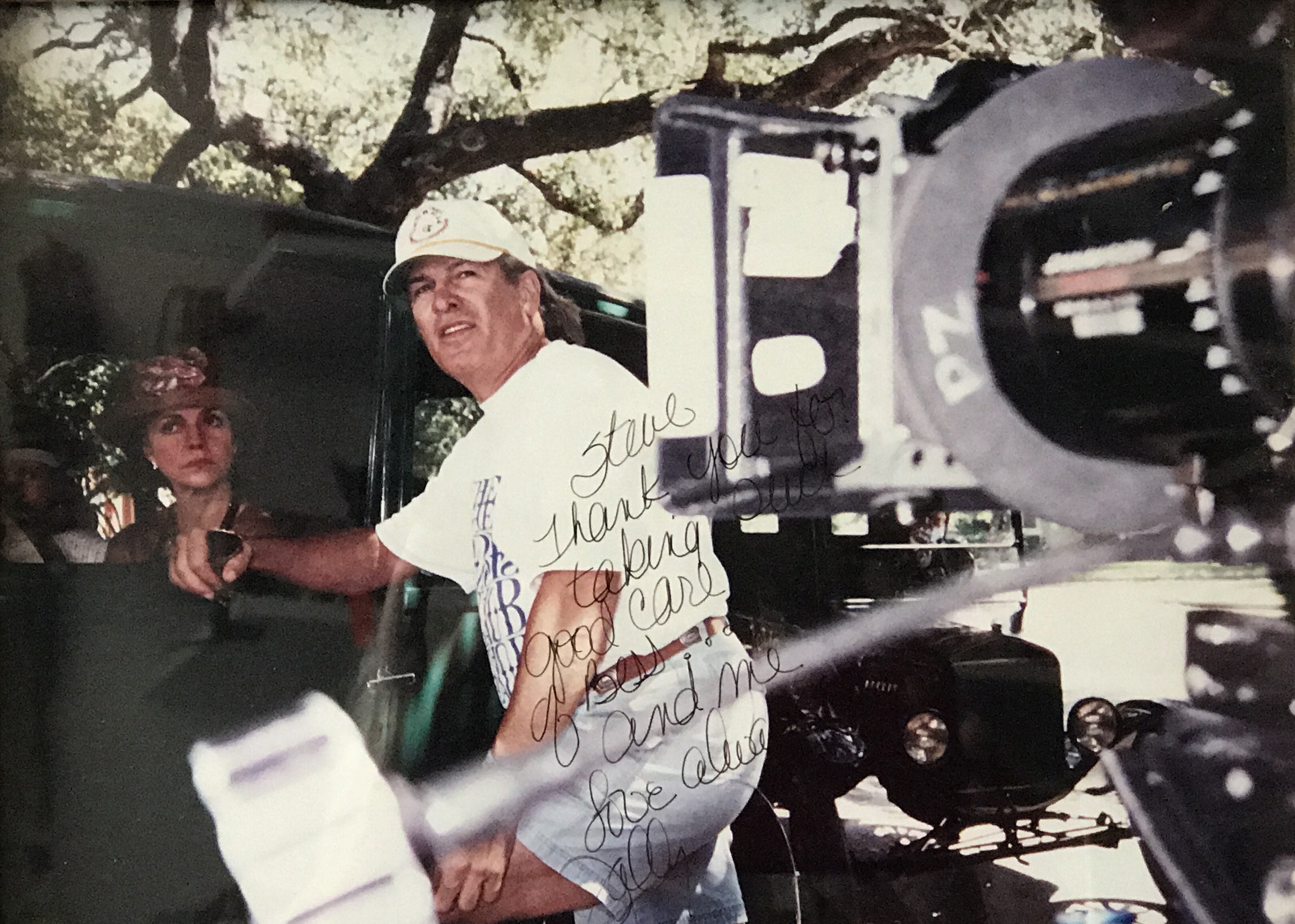

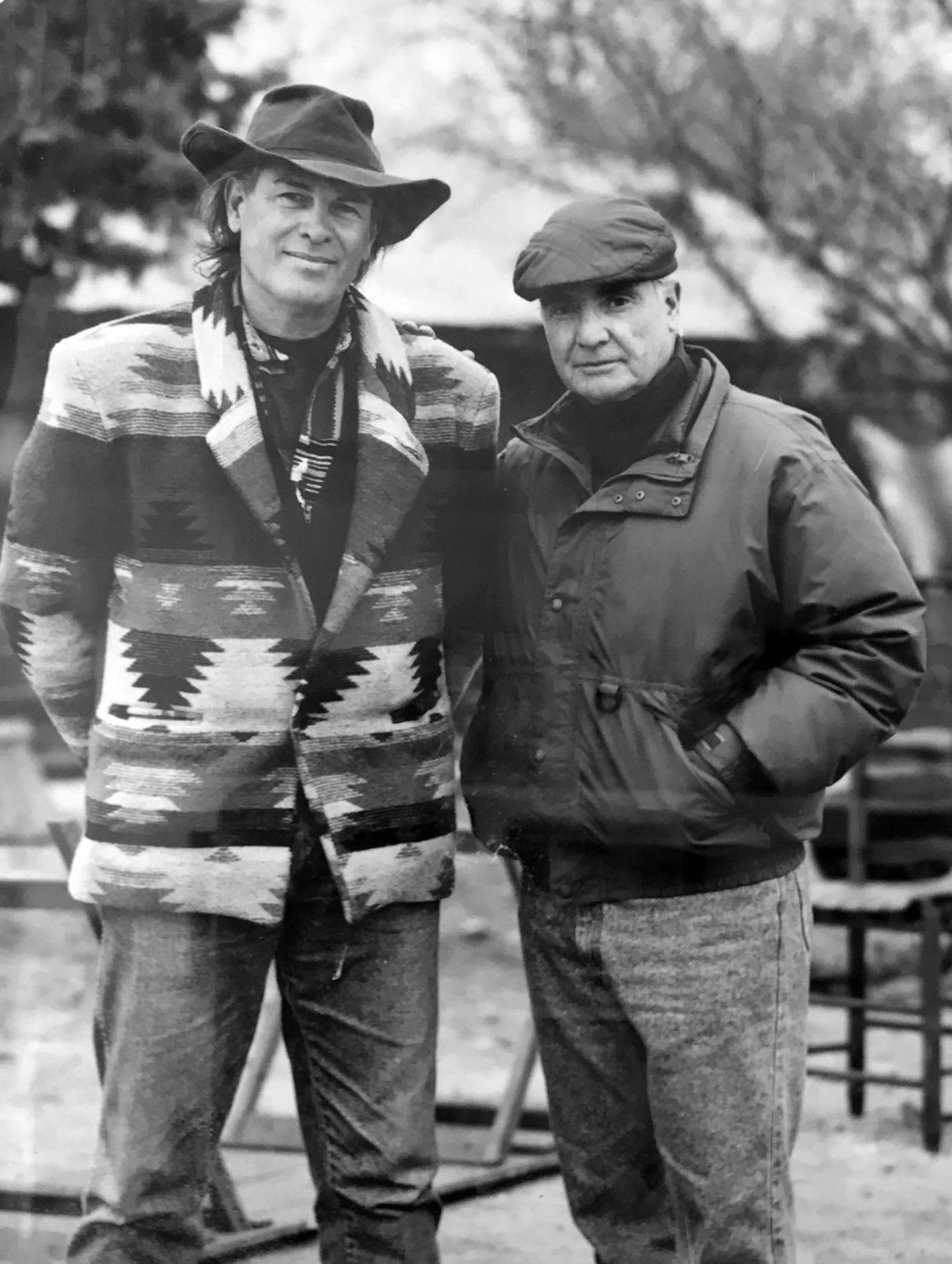

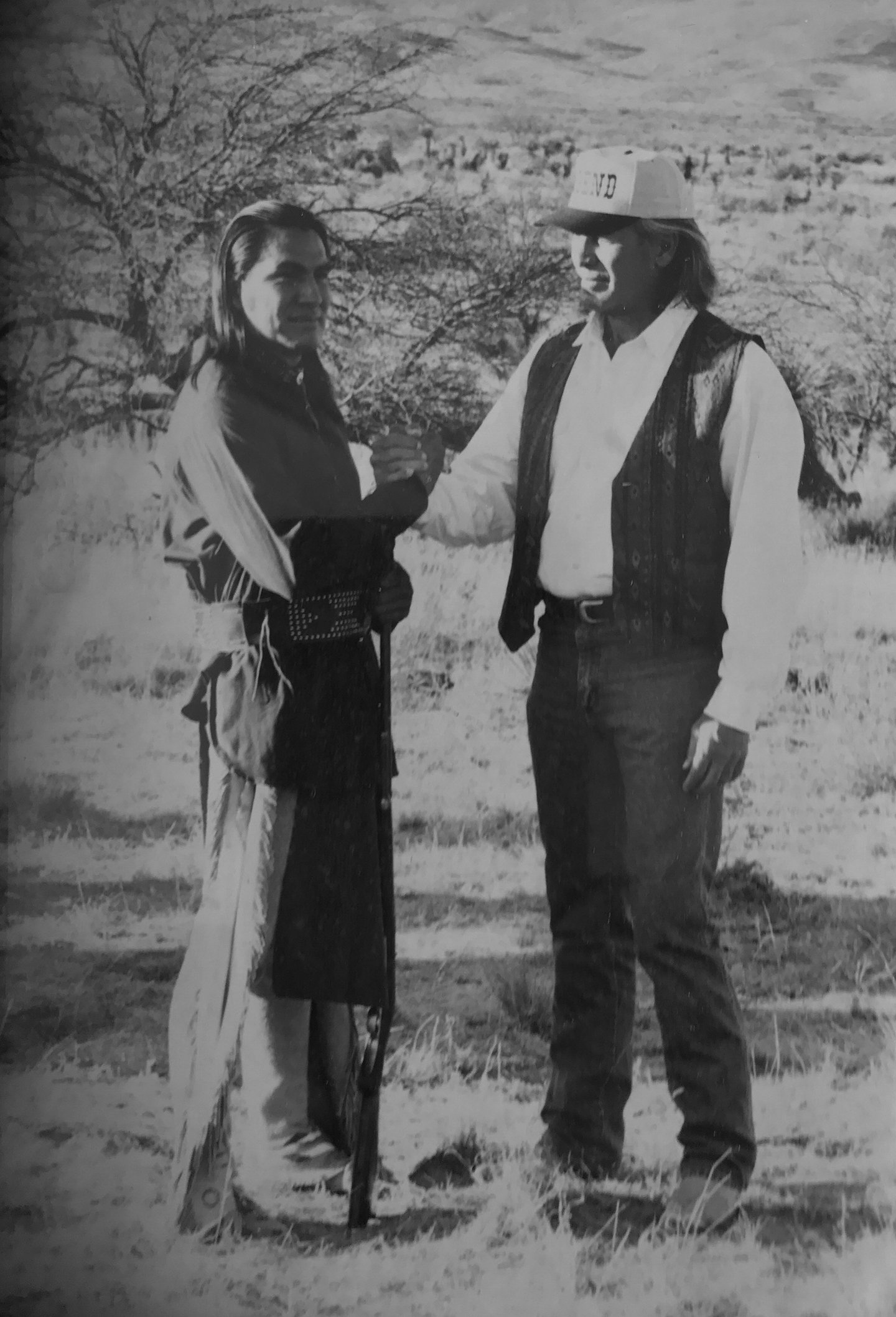

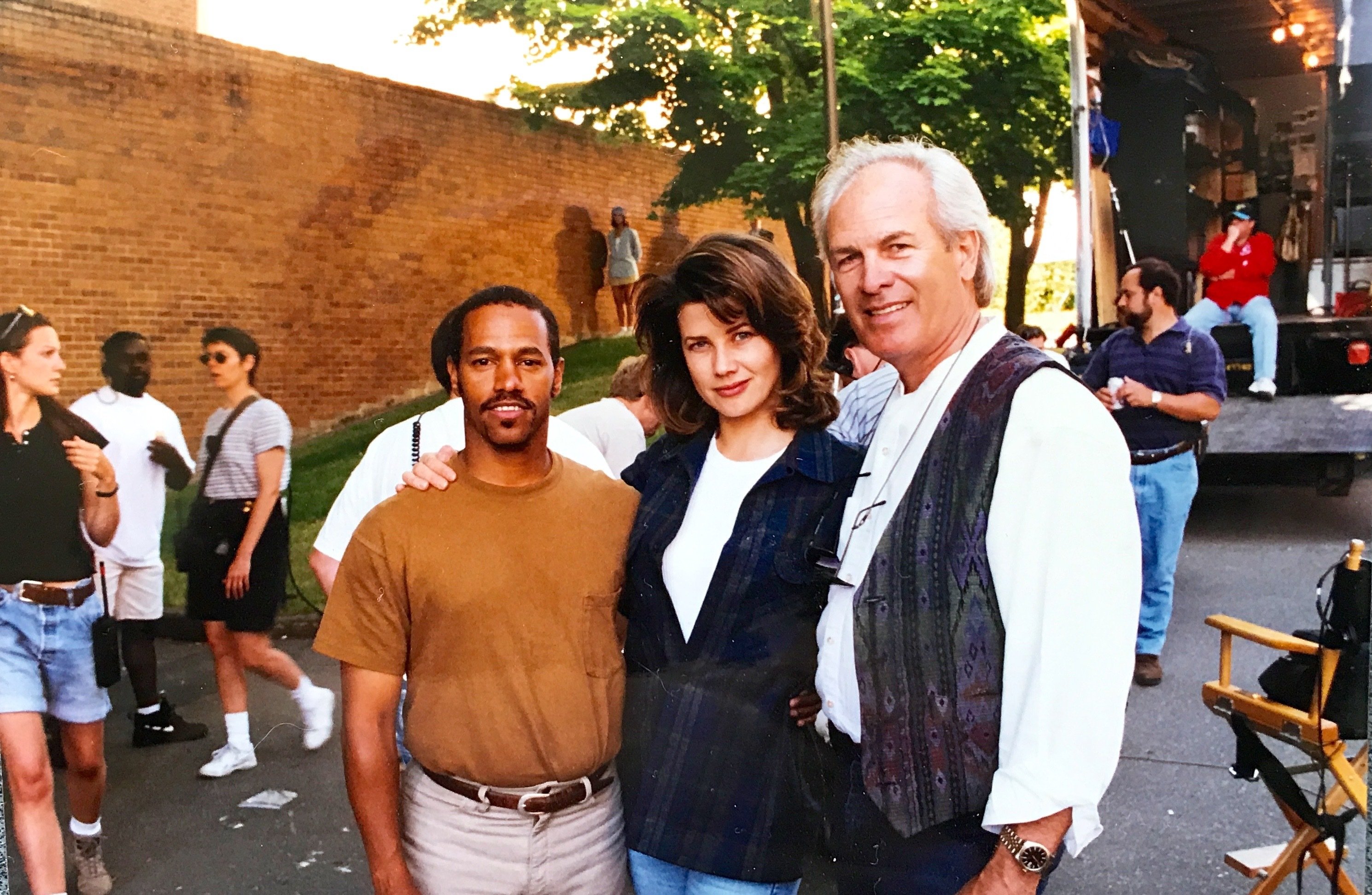

Images courtesy of Steven Shaw, ASC

The following is the transcript of Steven Shaw, ASC’s interview with AC, which served as the basis for his ASC Close-Up piece in our September 2017 issue. It was too good not to publish in its entirety.

I fell in love with Elizabeth Taylor in National Velvet. I think I was 6 or 7. It was my first experience being emotionally moved by a movie. Then, of course, The Wizard of Oz and all the kid movies. As I grew up, there was Rebel Without a Cause and the James Dean movies. My first real experience in grand imagery was Gone With the Wind — being a Tennessee Southerner, I was hooked. And, of course, I fell in love with Scarlett O'Hara and wanted to be Clark Gable. Then along came my favorite movie of all time — Lawrence of Arabia. That imagery has always stayed with me.

I went to Vanderbilt University on a football scholarship. There was no film school at Vanderbilt — you’re an engineer, doctor or lawyer. I was in engineering school, and the only A’s I made were in mechanical drawing. The math was cruel. I transferred out and went into liberal arts and joined the Vanderbilt theater program. The only A I made after that was in sculpture. I loved to make art with my hands. I sculpted a horse head and gave it to my father. He called it 'Rare A.' I think if I had to make a choice right now, if I had a studio, I would start working in sculpture. When I was young, I could always draw and paint. I had a cousin who was an artist, and I learned oil painting from him. I didn't pursue it; it wasn’t my passion, but I enjoyed being able to do it. It proved valuable years later when I could sketch storyboards quickly. I acted in the university theater, so I did a lot of plays.

After college I was drafted by the Cleveland Browns, but I came out of college very injured — my knees — thanks to Alabama. I had to make a decision whether to go into the service, as Vietnam was raging, or go to Cleveland and maybe make the team. I had taken ROTC in college, so I chose to take my commission as a Second Lieutenant and go into the army, and possibly go to Vietnam. I kind of wanted to go, actually — I don't know why.

I called Cleveland and said, ‘I’m not coming.’ They said, ‘Why?’ I said, ‘Because you want to change me to defense, which means I’ll have to tackle Jim Brown at practice and I think Vietnam is safer.’ They laughed and said, ‘All right, if you're going to go into service, we want you to go to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, and play football for one of our coaches.’

So I got orders to report to Fort Sill. And that’s where I spent my two years in the military. I had finished high in my class in officers’ basic, and they kept me Stateside to teach, and also to play ball.

I never reported to play ball — I was too injured — but I became very good with optics as a forward observer in artillery, looking through the scopes and being able to judge a distance. The life expectancy of a second lieutenant in artillery? Not long. Some stats say 25 minutes. You go out, you're on a hilltop, and you're calling in a fire mission — artillery on the enemy. If you can see them, they can see you. It was very dangerous, and I was thankful I didn't go to Vietnam for that.

After serving two years on active duty, I went back to Nashville. I was going to enter law school; I had no real desire to do that, but I finished high on the law boards. And then I met a country-music star/comedienne named Minnie Pearl — and also a high-profile Nashville attorney named John Jay Hooker, who was running for governor. He had created a company called Minnie Pearl’s Chicken and Roast Beef. I was dating his secretary, and I met him at a party. He said, ‘Steve, what do you do?’ I said, ‘John Jay, I wanna go to work for you!’ He said, ‘What do you know about the chicken business?’ I said, ‘Nothin’! And by the way, what do you know about the chicken business?’ He laughed and said, ‘Come see me!’ I had just enough scotch in me to be brave enough to confront him. He was magic — this guy was great. A Southern politician of the first order.

He hired me, and Minnie Pearl became my responsibility for the company — so I traveled with Minnie and we opened chicken stores all around the South. Then we came to California to do the Dean Martin and Johnny Carson shows. Dean Martin at that time had a lot of female dancers — they were called Golddiggers — and I fell for one of them. I had to come back. And I did — I came back and I tried to build a couple of restaurants. It didn't work, so I decided I needed to go to the mountains and become a ski instructor. All I had to do was learn how to ski! I figured I was a pretty good athlete and it wouldn't take very long, so I went to Mammoth Mountain to learn to ski. It took a lot longer than I thought.

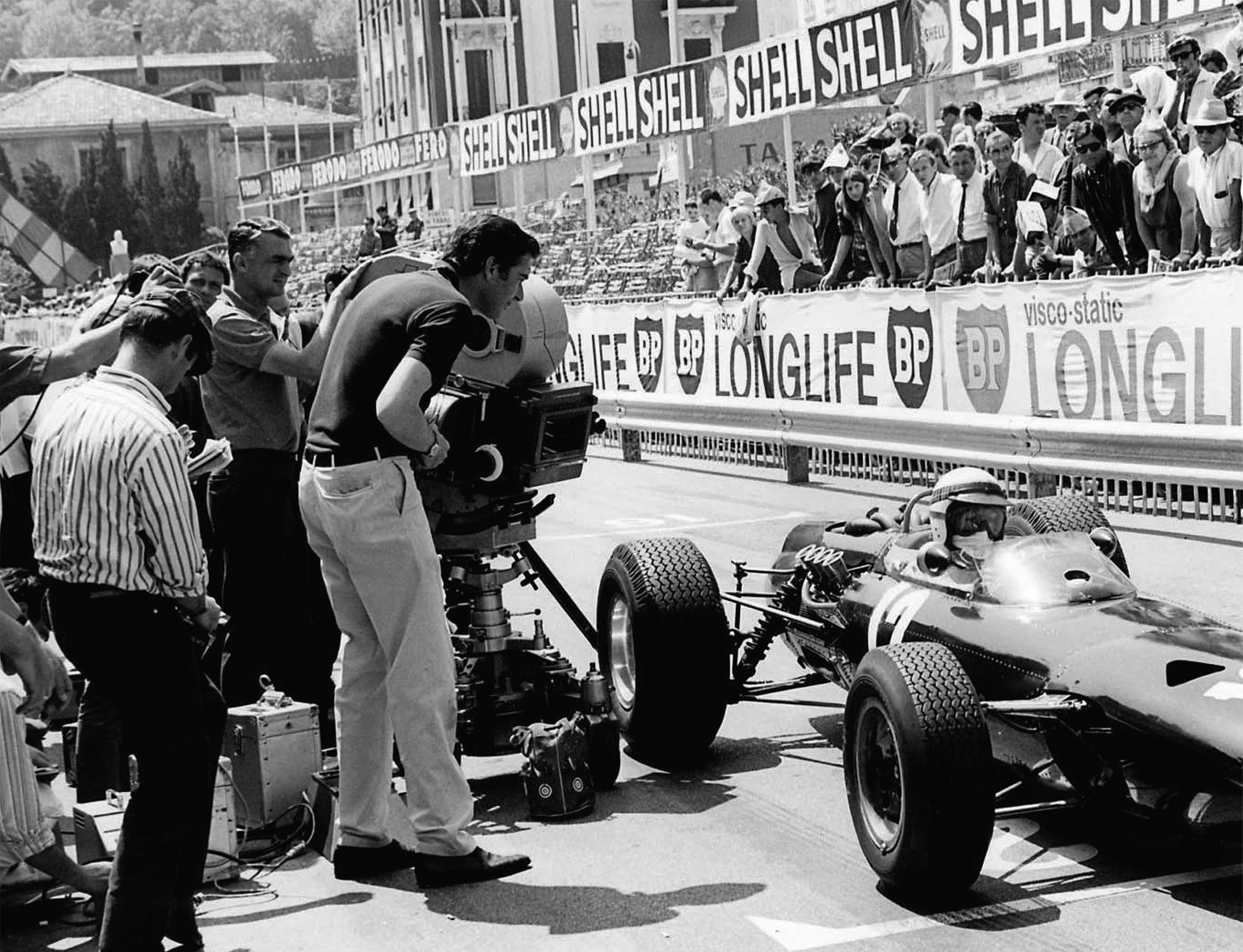

I met a cinematographer at Mammoth. He was a skier and we owned condos in the same building. His name was John Stephens and he had [used groundbreaking techniques to shoot racing scenes] on Grand Prix for director John Frankenheimer. He was a very hot commercial camera guy, who was doing a lot of commercial shooting in Europe, particularly for Porsche, Mercedes and Buick. He suggested that since I could fly for free — as my wife worked for American Airlines — that I should fly to Germany and he could get me on the payroll as a local. I said, ‘But Johnny, I don't speak German!’ He said, ‘It won't matter, I’ll get you on it.’ So I learned how to load an Arri IIC and Arri III in Munich, Germany, at a place called Dedo Weigert, which makes the Dedolight. [Company founder Dedo Weigert] remains a friend of mine. That’s when I first learned about cameras.

John had developed a remote servo-motor camera rig, so that going into a high-bank turn with a race-car, the camera could stay level. We were working with some Porsche cars that you could not touch, because they were one-of-a-kind, yet we were racing them around Nürburgring in northern Germany! Because of my engineering background, I was picked to design some camera mounts that had to come off the chassis. With the help of some German machinists and the hotel machine shop, we got them built.

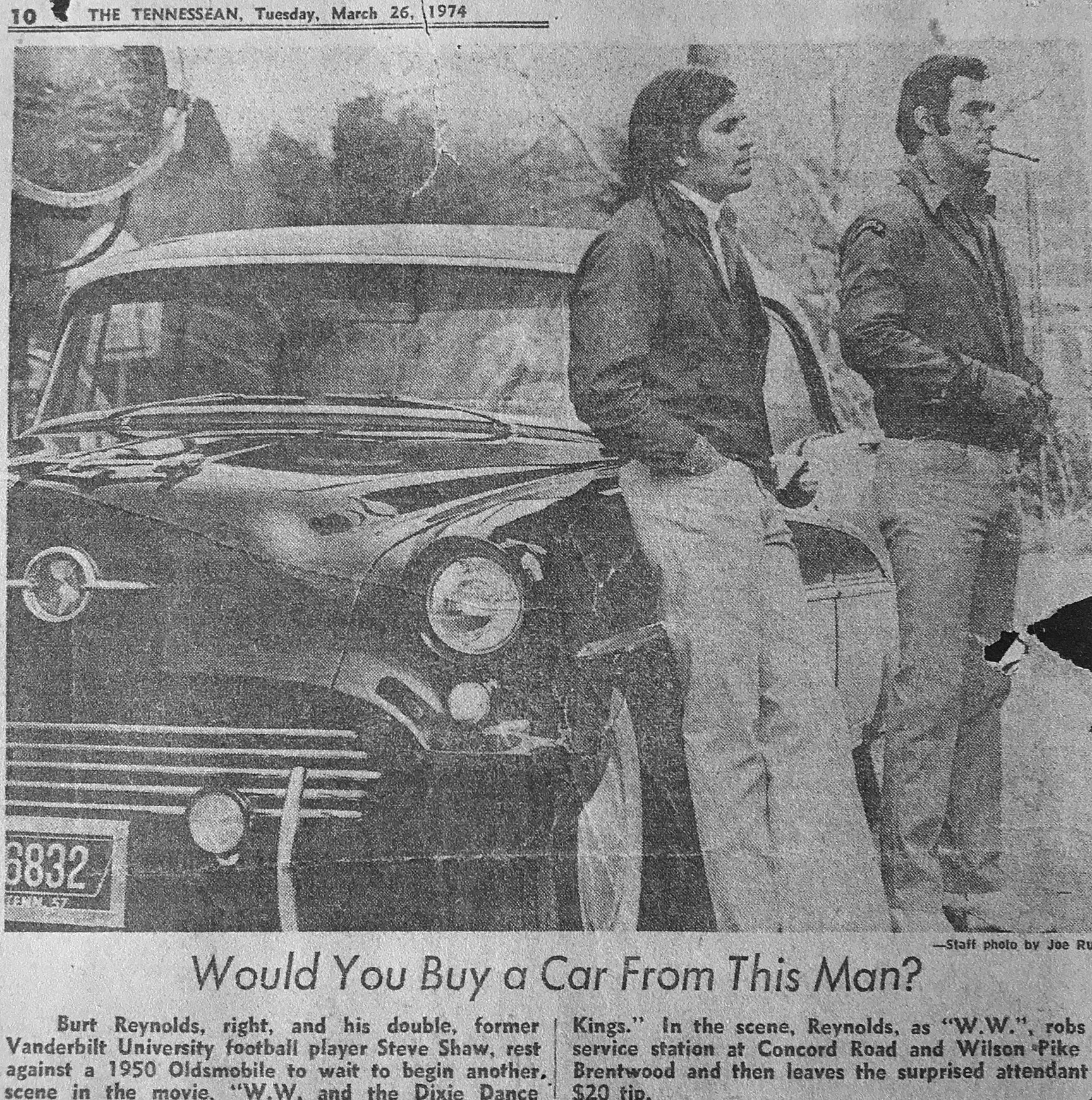

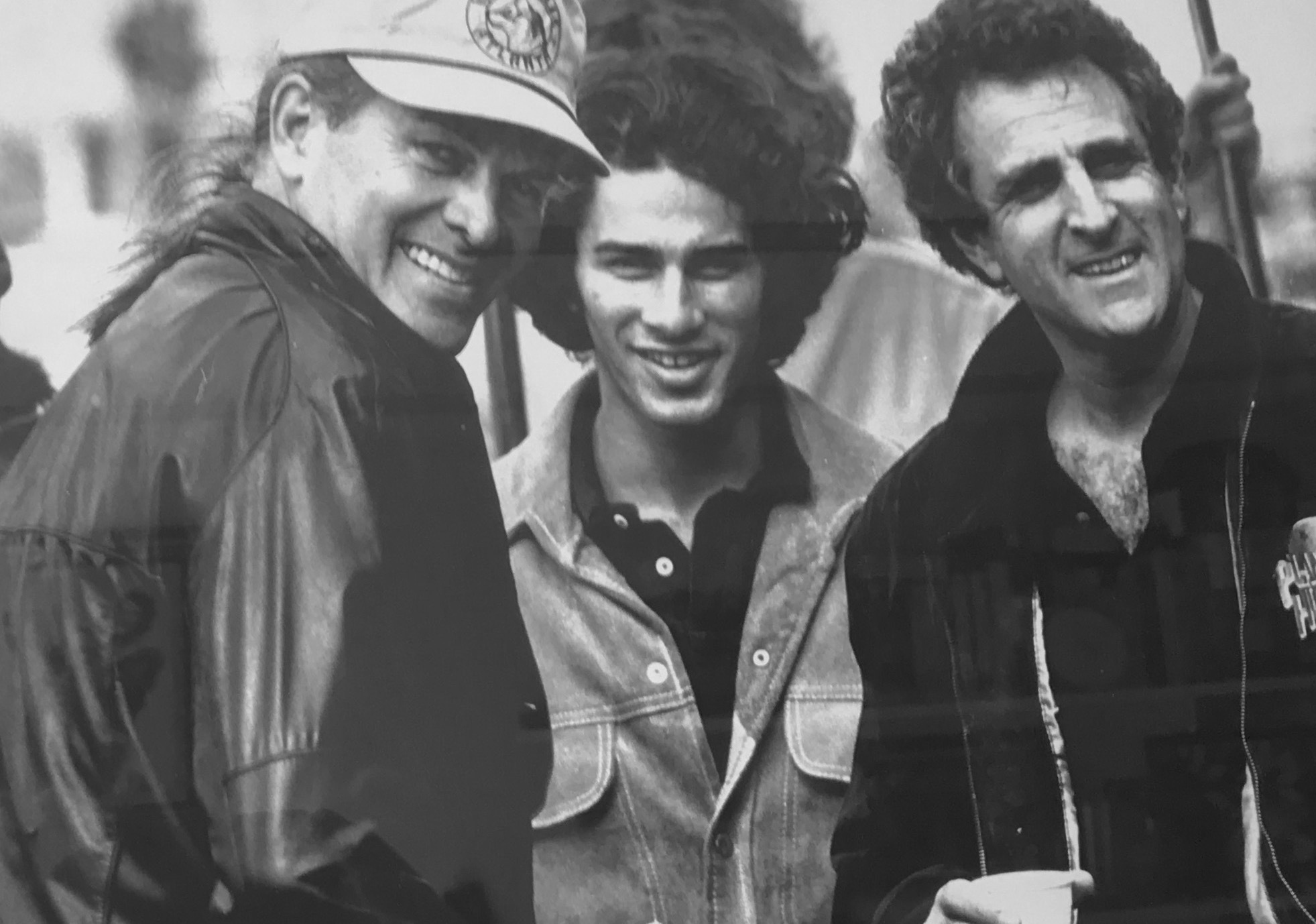

We came back to the States, and I met Burt Reynolds through production manager Robin Clark, and I ended up standing in and photo doubling for Burt on a movie called W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings in 1974, in Nashville, Tennessee. I went back and stayed with my family.

Burt liked me and I liked him. He’s one of the greatest guys ever, in my experience. I owe him. I did four movies with him — and in the meantime, I was doing non-union camerawork, during which I had an opportunity to work with John Alcott [BSC], who had won the Oscar for Barry Lyndon. He came over here to do little low-budget non-union movies; he wanted to get in the union and the union wouldn't let him in. I was not yet in the union, but I was becoming very proficient at focus pulling and being a key first assistant. I pulled for John and he was great. We shot a lot of stuff at night; he was a generous teacher. And that’s how I really got started in the cinema business.

On a film called Lucky Lady with Burt, Gene Hackman and Liza Minnelli, which we shot in Mexico, I became more of a stunt guy than just a photo double for him — Hal Needham and I both, but Hal couldn't grow a mustache and I could, and we had water work so it was just easier for me to do it. Burt also made sure I always got cast as an actor to say a line or two — I actually had a very short dialogue scene with Liza. When you looked like he did and were number-one [at the] box office in the world, things were great fun.

Burt wanted to make sure he was looking good [on Lucky Lady], and he sent me to dailies every day. The cinematographer on that movie was an Englishman named Geoffrey Unsworth [BSC] — who, when I met him, already had an Oscar for Cabaret. So for several months, I followed him around like a puppy. One day he asked, ‘Steve what’s your game?’ I said, ‘Geoffrey, when I grow up I just wanna be like you.’ He said, ‘Well, you know I have two ex-wives.’ We laughed. Geoffrey was a great cinematic inspiration.

He and I would sit and watch film dailies on location, and I could ask any question about filters, lenses and technique; light and shadow; actor movement; camera movement; film stock; etc. It was one-on-one for around four months. He’s the guy that really inspired me to dedicate myself more towards the magic of cinematography. Plus the fact that Burt wanted me to learn how to wrestle an alligator for his next movie — which he was going to direct — called Gator. I said, ‘Burt I love you brother, but I ain’t wrestling no damn alligator.’ And that’s when I went more toward camera. The next time I saw Burt, years later, was on Sharky's Machine, shot by Bill Fraker, ASC. I was the aerial assistant. Burt was directing. It was a great reunion.

Laszlo Kovacs, ASC was the cinematographer for Peter Bogdanovich on At Long Last Love, starring Burt Reynolds. I was a non-union first-assistant cinematographer at that point, and I watched Laszlo and studied him. In fact, I studied every cinematographer I worked with when I was with Burt, and took notes. I never asked Lazslo a lot of questions when he was working, but when I’d get an opportunity after the shoot, he was happy to entertain my never-ending questions. Laz was another teacher at my on-the-job ‘film school.’

[Shortly after At Long Last Love] Bill Friedkin had hired a cinematographer from England named Dick Bush [BSC], who came to L.A. to do some tests for Sorcerer, for which I got the camera equipment from cinematographer John Stephens, and we shot them. It turned out that that camera equipment I borrowed got John introduced to Billy Friedkin, and Johnny got hired to shoot second unit on Sorcerer — and I was hired as the aerial camera assistant on Continental Camera Systems. Gerry Smith, who was president of IATSE Local 659, gave me permission to work for three weeks. Our three weeks in the Dominican Republic turned into three months, because Dick Bush left the show, and we got moved to first unit. When we got back, I applied for membership in the union, and was not allowed, because I’d gone over my three weeks — so I had to sue my way in, which I did.

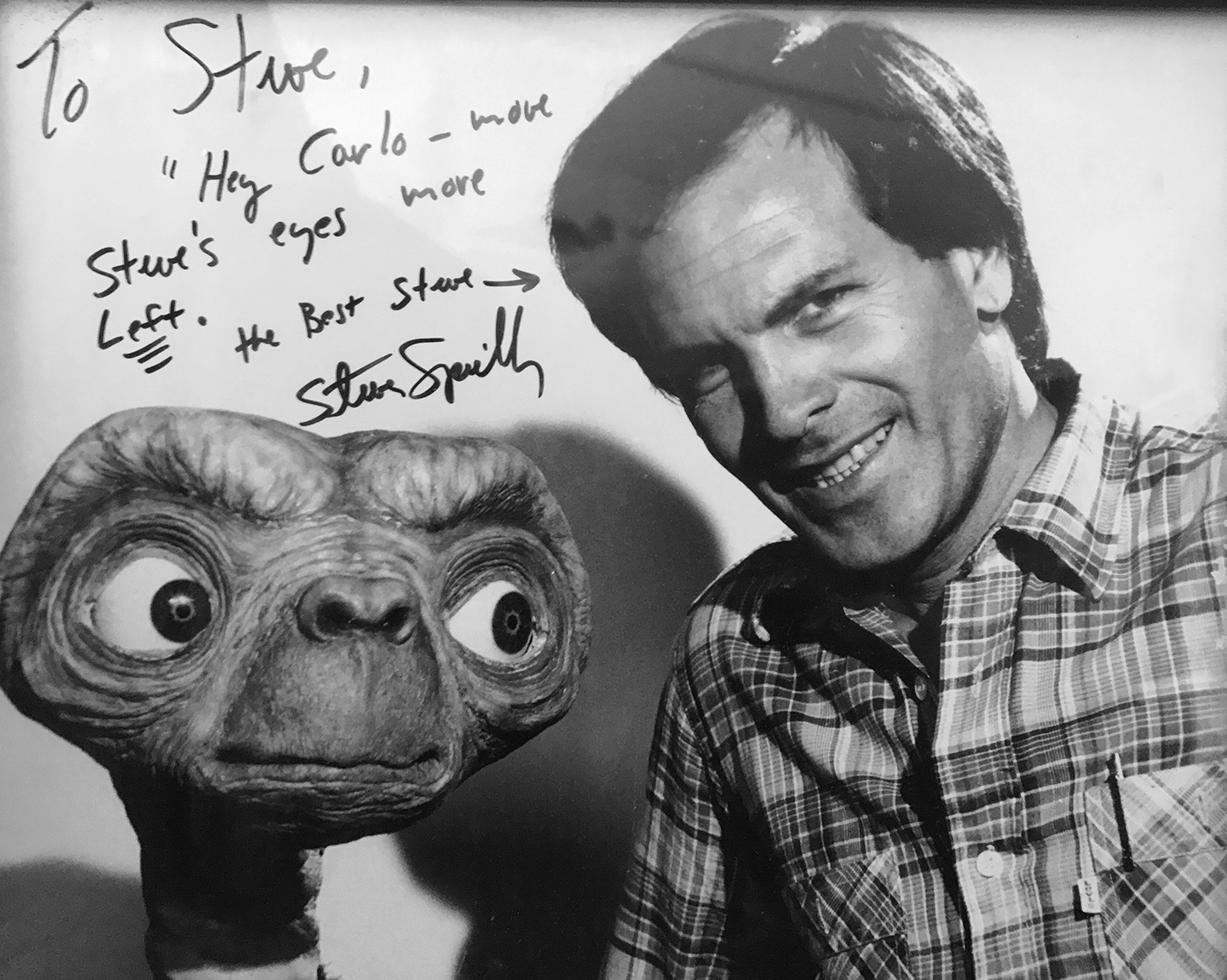

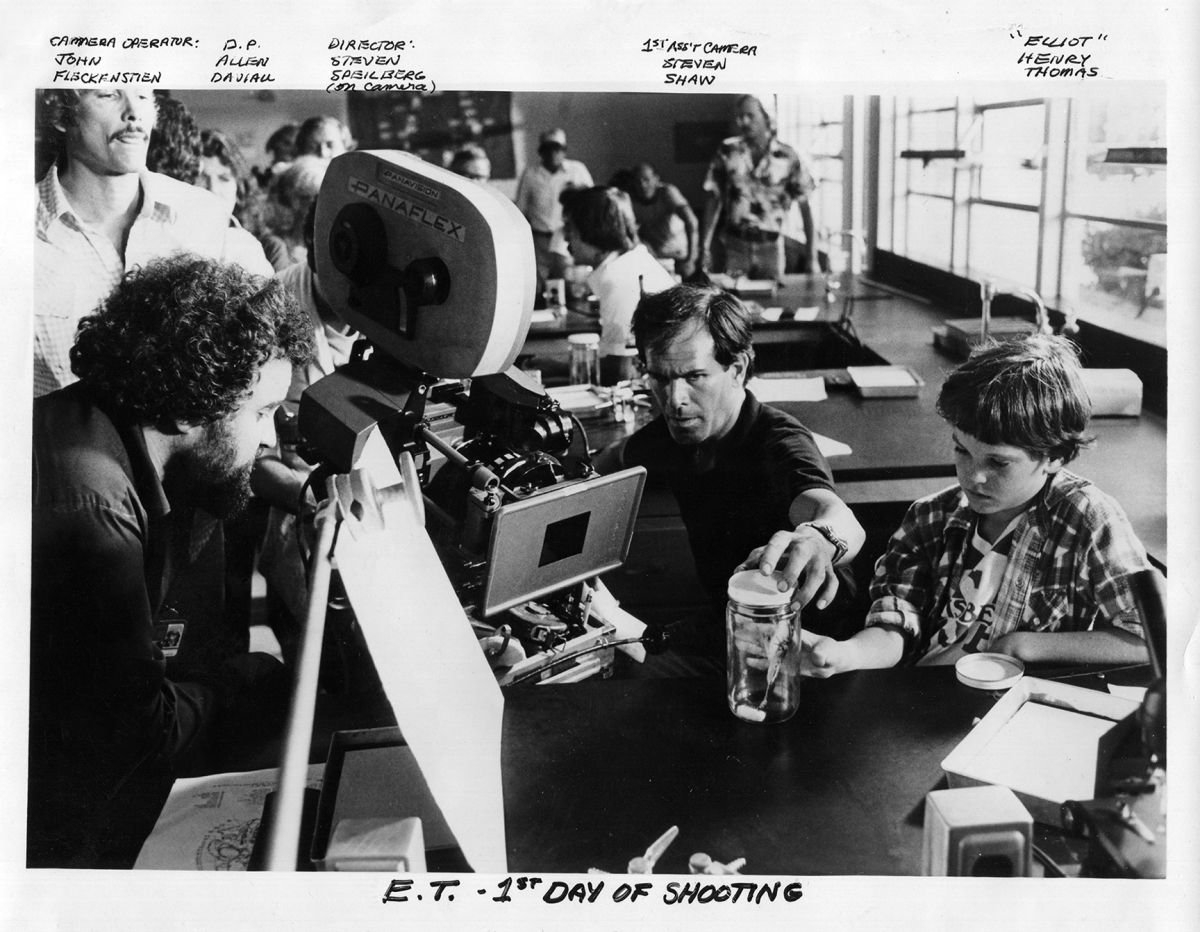

Then I met Allen Daviau, ASC and I spent the next five-and-a-half years with him. We did tons of commercials. We did one movie of the week, and then he got his break to do E.T. — so I became the focus puller on E.T. It was a sweet position! You’ll ask any focus puller in town, Steven [Spielberg] is not easy, but I survived it!

Every other day I’d say to Steven, ‘You know, this is going to be a big movie.’ He said, ‘No, no, it’s my little movie. It’ll do okay; it’s not going to be great.’ I said, ‘I think it’s gonna be great!’ He said, ‘Why do you keep saying that?’ I said, ‘Because we all like that little guy — everybody on the crew. The little E.T. guy, he’s adorable! Every kid in America is gonna see it twice and take a parent twice. Just count the tickets, you don't have to be a genius.’ It spent 20-plus years as the highest-grossing film.

After E.T., I knew I didn't want to pull focus anymore. It was time to move up. My first operating job was on a Ken-L Ration dog commercial, and Arthur Ornitz [ASC] was the cinematographer. He was a New York cameraman — a crusty, hard-assed old S.O.B. who was great. He had shot Requiem for a Heavyweight. Good guy. That was my first time really operating for a big name. I loved operating.

But it was E.T. that got me a shot to shoot a low-budget teenage horror movie. I interviewed with a director, Nico Mastorakis, who didn't have much money, but he wanted to shoot nighttime — 18 nights in the woods — and somebody recommended me, I don't know who. [Mastorakis] said, ‘I want my movie to look like E.T.,’ to which I said, ‘Well, I was there every day — maybe I can duplicate it.’ He said, ‘You were there? Every day?’ I said, ‘Yeah!’ He said, ‘You're hired!’ He hired me as cinematographer and operator — two jobs I had never done, but I didn’t tell him that. It was a low-budget feature film on 35mm negative, and it turned out pretty good! My secret was I had a terrific gaffer, Larry Wallace. Daviau ended up stealing him! That was my first feature film. It was called The Zero Boys.

That led to movies of the week. Robert Greenwald hired me to do them, and I met directors, got an agent and just started shooting. I stayed very busy for around 15 years. Most people spend a long time trying to get to movies of the week, but I was lucky — I started there. Then I got offered a television series for NBC called I’ll Fly Away, shooting in Atlanta and starring Sam Waterston. I wanted to do it because of Sam, because I loved him as an actor. Also, it was set in the South, and it was during the time that I was in the South, when I was raised, in the Fifties. I loved that show, and it was a long run of steady employment.

But [after] one season, I had to leave that show to do a feature for Robert Greenwald, the producer who had given me my first movie of the week. He said, ‘I got a feature! You’ve gotta come.’ I said, ‘But I’m doing a series!’ ‘Tell them you owe me,’ he said. And I did, so I called my agent and said, ‘You have to get me out of this.’ It turned out not to be a good thing to do, to leave a series, especially when it’s successful. And I was really proud of the cinematography, because it was really dark and moody, and they let me do that on this show. It was a great opportunity to light using strong shadows and contrast. Shadows were our friends. So that led to a continuation of more work — but the producer of the TV series never truly forgave me. Even though we played golf together and were friendly, he nailed me to the cross down the road.

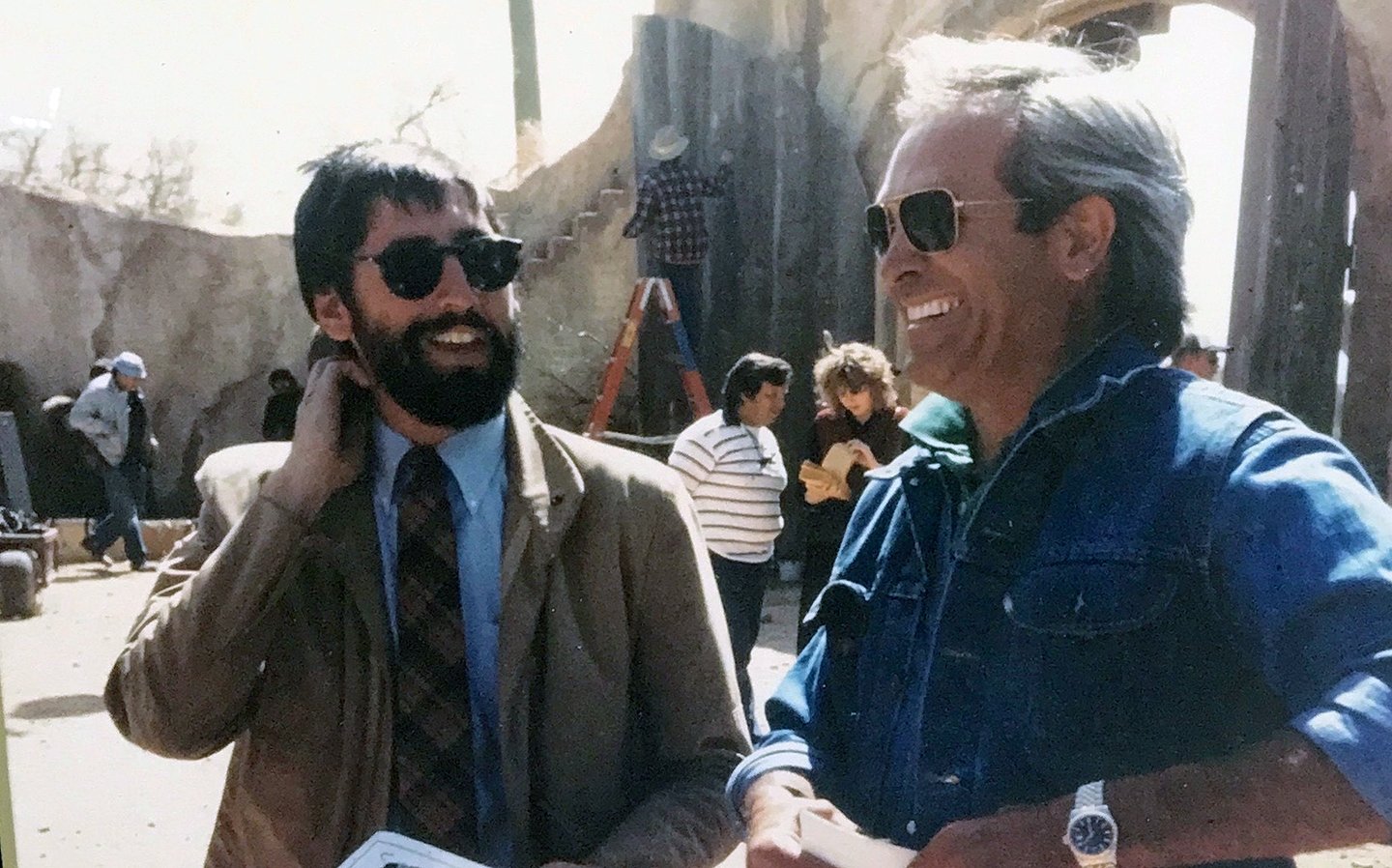

There was one great, big feature that I got hired to do. John Frankenheimer hired me to shoot second unit on a movie called 52 Pickup with Roy Scheider and Ann-Margret. The only reason I got that job in the first place was I was dating Frankenheimer’s secretary’s daughter. She got me in the office to sit with him and talk film. We talked Citizen Kane, The Manchurian Candidate — the black-and-white great ones.

Jost Vacano [ASC, BVK] was going to shoot first unit, but they were having a hard time getting him in the country — the H-1 visa. One day Frankenheimer says to me, ‘You're going to have to start scouting for Jost.’ I was pretty fresh in the business on that level, and I was more than a little bit intimidated — but I started [presenting] my ideas and Frankenheimer liked them. Then one day, he came to work and he said, ‘I screened Zero Boys last night.’ I said, ‘What? My teenage horror movie?’ He said, ‘Yeah, I screened it. It’s not my [kind of] material, but I think you could shoot my movie. And if I can’t get Jost in the country, you're my guy. I said, ‘Oh, my God!’ Yes, I was intimidated. Yes, I tried to hide it.

Then Ann-Margret wanted to do a makeup test. This led to a very low moment in my career. She had to leave for Hawaii the next day and wanted to shoot it at 10 o’clock at night at Paramount. I had never shot a makeup test, so I called Daviau, who was in London with Spielberg on Empire of the Sun, and I said, ‘Allen, what do I do?’ He said, ‘Make sure she’s beautiful! Because if she’s not beautiful, she’ll get you fired.’ So I said, ‘Okay.’ I went up to her with my light meter, reading the light, and she whispered into my ear, ‘See this hole in my cheek?’ It was where she fell off the stage in Vegas and she got a chip in her bone. She said, ‘I never want to see it.’ And I said, ‘Well, Miss Margret, I can do that.’ It didn’t seem right to make her beautiful for this material, but I was afraid not to do that — so I made the mistake of departing from what I do. I over-lit her. We looked at the makeup test and she was gorgeous — in a cosmetic, commercial sort of way. And Frankenheimer fired me. I was crushed. It broke my heart, and for six weeks I was dead. For making Ann-Margret look too good. He wanted hard light; he wanted to see the hole. My mistake — one that I never made again. Every makeup test after that, it was various forms of light, not just one.

[Since then, when I encounter similar situations] I start off trying to make an actress feel very comfortable. Back when I thought I wanted to be an actor and I was taking acting classes, I spent a good deal of time in that process, so I kind of knew what actors go through. [As a cinematographer] if I had a young lady that was scared, I would make her feel comfortable and encourage her. If I had an older actress, like Sally Field — I did a six-hour miniseries, called A Woman of Independent Means, with her, with around a $25 million budget. A big deal. I had to sit down with her before I got hired, and we talked about light, shadow, texture, color, all that stuff, and she felt very comfortable with me and I felt comfortable with her. She and the director wanted to shoot a hair and makeup test. But I have never forgotten that moment with Ann-Margret. An actress would ask me for something, and I’d say, ‘I’ll always do my best for you, but if my director wants it a certain way, I’m going to give it to him, too. I’ll balance it out. I’ll take care of you — don’t worry.’

So after 52 Pickup, I went back to movies of the week! Then I headed to Portland to do a feature called Hear No Evil with Marlee Matlin for Fox in the early ’90s. And I started doing more television series after that — and doing series really paid off. I don't like high key and a lot of light, and on all the series I did, I was allowed to do the ‘mood,’ the darkness.

I was on a six-hour miniseries, shooting in Europe with a director who will go unnamed, and after day three we were a half-a-day behind, because we started on water. It's deadly to start on water — no matter who you are or where you are. My phone rings at 4 o’clock in the morning and the director says, ‘I’m going to be fired today. What do I do? You’ve done television, and I never have — I don't know how to do 10 pages in a day.’ He was a friend of mine, so I could talk to him like a friend, and I said, ‘For one day of your life, you just have to give up to me. I will pre-light sets, I will leapfrog sets, I will design the day. I will AD it, I will shoot it, and I will camera-operate it. I will never say ‘cut,’ because that’s disrespectful to the director in front of the cast and crew. You’re the director, but you’re also acting in the piece today. So I am your director, Mr. Director. And though I will never say ‘cut,’ I will say, ‘got it, that’s it, we’re moving’ — and you must not ask for another take. If you want to make up this page count, we have to move on my schedule.’ And we made it up! And that night he said, ‘I loved today! Today was great!’ I said, ‘Of course you're gonna give me half your paycheck, right?’ He laughed and said, ‘No way!’

I don't care who you are or where you are. If you start on the water, you're going to be slow. And if it’s raining, it’s really going to be slow. So the thing that I’ll always lobby for with an assistant director, as far as scheduling, is a cover set on day one. If it's a day exterior and there’s a possibility of rain, we’ve got to have a cover set — because we’ll fall behind on day one, and you can't do that. It could be a new crew, and maybe the production manager did not give you a day of pre-lighting or pre-cabling, and if it’s an exterior the weather might be wet and muddy. Those take a whole lot of time, so I lobby hard for proper preparation. The first day is really important to not start off with something so complex that you get buried.

I became a DGA-member director while working in series television, [on such projects as] ABC’s Crossroads, Paramount’s Legend and Fox’s 413 Hope Street. I would usually get one or two episodes to direct. Aaron Spelling called me in Atlanta once and said, ‘The director’s sick today; is it possible you could shoot and direct? I said, ‘Yes, sir. Not only is it possible, it's preferable — because I don’t have to waste time having conversations with the director, and for the first day you won’t have any overtime. You’ll like the performances, I’ll get the work done, and you’ll likely have no complaints. And if you don't like the performances or the coverage, please let me know. No problem!

From there I went on to direct two episodes of The Lazarus Man for TNT, starring Robert Urich, a man who became one of the most valued friends in my life. He is deeply missed.

I learned that shooting television for Aaron Spelling is different from shooting television for Robert Greenwald — or David Chase, who went on to do The Sopranos. David Chase came down to Atlanta on I’ll Fly Away. He was the executive producer/show runner, and he got an episode to direct — and he said, ‘Steven, I want to do this, but my producers tell me I can't.’ Jokingly, I said, ‘But David, you are the producer! I’ll tell you what — don't let anybody stand in the way of your vision. You be creative, and don't worry about the mechanics, don't worry about lighting at night, don't worry about that stuff. You just share with me your vision, and I’ve got a bag of tricks. Let me figure out how I can give it to you. But don't be handicapped by what the others tell you you can't do.’ And we’ll get it done!

Vilmos [Zsigmond, ASC, HSC] had it right: Keep it simple, stupid. I always tell my camera operators, ‘Keep it simple, keep it perfect.’ Composition is really critical; I don't want a bunch of headroom, and I don't judge Steadicam guys by how good they move, but by how good they stop. If you can stop solid as a rock, you’re my guy. I don’t want a ‘Good Ship Lollipop’ Steadicam operator.

I would always make sure that the B camera was a Steadicam — because I operate. I use the wheels, which is rapidly becoming a lost art with the young — plus no operator can operate as well for me as I can for myself. And I can make mistakes and nobody knows about it but me. ‘It was an experiment! We’re gonna need one more!’

When I teach, or lead a workshop in Dubai, or [serve as] an ASC Master Class ambassador, I always refer to Freddie Young [BSC]’s work in Lawrence of Arabia. It’s great imagery to display to a class when I want to demonstrate the idea of, ‘Can you tell this story without the actors having to speak? Do you get the emotion from this story from image only? And what is it about the image? The light? The shadow? The color? The positioning? The movement or the non-movement of the camera?’ And when I read a script, I’m thinking, ‘Could I shoot and communicate this script without dialogue?’ I flash back to 1927 — a film called Sunrise. They did Steadicam-like moves in 1927, but they weren’t Steadicam — they just look like they were. And they painted shadows on the stage floor, and it looked like the sun was out, but it wasn't. The old studio guys had some great tricks.

I always flash on In Cold Blood and that accident with the bleeding raindrops down Robert Blake’s face. Accidents happen, and that’s why I always encourage everybody to pay attention all the time. If I take my eye off the eyepiece, I want to see my keys looking at me. I don’t want to have to call their names — I can do hand signals. And I hate a loud set. Some people like music playing, but I want it quiet.

I was raised in film — film is what I know. When students ask me about the difference between film and digital, I tell them: When they get on a plane, fly to Amsterdam and go to the Rijksmuseum, go up to the third floor, take a seat, and study a particular oil-on-canvas painting called ‘The Night Watch’ by Rembrandt. If you sit in front of that painting, as I did, and you study the light, shadow and color tones, and the expressions on the faces of every one of those 17 or 18 people, every one of them has different light, shadow and tones, and every one of them is alive. If you pick out one little face and study it, it has emotion. Now that, for me, is film. Film is oil on canvas. Digital is not. I say that because that’s just my interpretation of it. The truth is, digital can come pretty damn close to tricking me.

Around three years ago, British cinematographer Dick Pope [BSC] was up for an Oscar for Mr. Turner. I watched that movie, not on the big screen, but on the ‘movie’ setting on my big-screen at home, and I was just blown away at how beautiful it was. Then he was over here for the ASC Awards, and I have friends of mine with me — young filmmakers — and I stopped Dick Pope in the front yard of the ASC Clubhouse and I said, ‘Dick, I gotta tell you, that was such a beautiful film.’ I turned to my friends and said, ‘Look at his interior, his exterior, his exposure. You can't do that with digital!’ And he said, ‘Well, Steve, I don't know how to tell you this — it was digital.’ I said, ‘Dick, no, no! It can't be!’ Then I said, ‘Brother, you are an example of what can be done in the hands of a master.’ He thanked me and said, ‘That was my goal — to make it look like film.’

I think the hardest part for all cinematographers now is having control and being there in the end of production. Which is why I think ACES, the Academy Color Encoding System, is going to give us [more opportunities]. Instead of taking three weeks to do it, we can do it in maybe three or four days, because of ACES. I’m encouraged by that. Not that ACES doesn't have some problems, but it's being worked out.

Another great thing about shooting on film: directors say ‘cut.’ Actors want to hear ‘cut’; everybody wants to hear ‘cut.’ With digital, you never hear ‘cut’ anymore. There’s something magic about film. The magic is, ‘Roll the camera.’ You hear the camera operator say, ‘Speed! Mark it!’ You hear the clap. Now the pressure’s on and money’s rolling through that film camera. The pressure is everywhere to perform at the highest level for next minute, or 10 minutes. It’s the magic of film, and I think that’s what’s missing today.

I'd love to shoot film — if they would give me a Panavision camera, a set of lenses and four people, and a lighting department and a grip department, I can make you a beautiful movie. But what you cannot have, Mister Director, is a monitor. Steven Spielberg did not have a monitor on E.T. We didn't have video-assist on those cameras; we did it the old-fashioned way: Stand by the camera and stay close to your talent. That’s what I miss about film — the pressure and the magic. It's great, it really is. And an actor wants to hear ‘cut’ from a director who’s not 50 feet away.

My most satisfying moment on a project — well, I had two of them. They were different types of events.

On a television series, I’m sitting on the dolly and I get a big kiss on the cheek from this guy. It was the star — a big star, too — and he had come running down the street after looking at dailies from the first day. He loved how different it looked, more than anything he had ever done.

I had used a technique that I learned from Peter James [ASC, ACS], who was also one of my great influences, if you’ve ever seen Black Robe. When I was an assistant, Peter taught me how to use nets behind the lens. These were stockings you had to get from Paris. They were good because they did not have fire-retardant chemicals. We don’t normally use netting behind the lenses for a television series, but I wanted day-one to be really spectacular. And it was. A kiss on the cheek.

The other great moment I had was [on] A Woman of Independent Means starring Sally Field. The problem, in general, for the director of photography is not having adequate [time for] prep. We might get a week, two weeks or a month. If it's a big movie like King Kong, you’re going to have a lot of prep. But on this miniseries, our first day of shooting was August 1 in Houston, Texas, and my first day of prep was April 1. I had done a lot of work with the director, Robert Greenwald, and because he was also the producer, he knew the value of proper prep. We went to Houston for the first two weeks of every month. We played the parts, walked it and talked it. I laid it out in military form on overlay — actor movement, lighting techniques, dolly moves, Steadicam, all laid out.

NBC’s got like 25 million dollars invested in this whole project, and we get on the bus to go on the tech scout with 12 to 15 [crewmembers] and three executives from the network — and the director decides not to go. And they go crazy. The executives said, ‘What? The director’s not coming?’ Robert came out of his office, walked to the bus and said, ‘Steve knows the answer to every question. He knows what we’re going to do and how we’re going to do it. I’ll be happy to answer any questions when you get back. And it took about half of a day, at the first or second stop, before the executives relaxed. We went on an eight-day scout without the director. If you have enough prep — and prep is the thing we don't get enough of — it’s big money in the bank. And Sally Field was really happy, and that was a high moment for me. She also said, ‘I can’t believe how fast you are.’

I did have one really scary moment in my life. The [1990] film was for TNT, and it was called Forgotten Prisoners: The Amnesty Files. It was shooting in Budapest [which stood in for] Turkey. I had gotten an emergency call from the director/producer, because his Hungarian cinematographer suddenly was no longer available. I arrived two days later, ready to start — with zero preparation — to discover that the next day we were going to slip into Istanbul and shoot three days and two nights without script approval from the Turkish government.

Our movie took place in Istanbul, and the government had denied script approval, but the director wanted to sneak two cameras in and shoot anyway. I said ‘okay,’ so we go in. Five of us — myself, an assistant, the director, wardrobe, props. I’ve got an Eyemo and an IIC, and we shoot several thousand feet of film. I’m night-lighting with headlights.

And now it comes time to leave Turkey. I thought I should divide the film up among everybody, but then I thought that some may not get through, so I’d better take it all — and if I don’t get through, at least the director knows that he needs to reshoot it somehow.

I had an interpreter, and he dropped me off at Ataturk Airport, and said, ‘See ya later.’ And I said, ‘No, no, no. You’re coming with me. We have three checkpoints we’ve got to go through.’ We made it through the first two, no problem. The third checkpoint, I got put up against a concrete wall with a machine gun in my face, and a Turkish guard screaming at me. They’d opened up the duffel bag and they saw the cameras, lenses and film — the whole package.

My interpreter is trying to convince them it’s home movies, and I’ve got my hands up and I’m up against the wall. I’m flashing on Brad Davis from Midnight Express. I’m gonna have electrodes attached to my you-know-what, and in about three hours I’m gonna tell ‘em anything they wanna hear! I see that my interpreter goes over and picks up the phone, and makes a phone call. He sets the phone down and two seconds later, another phone rings. One of the security guys picks it up, listens, slams it down, walks over, and says, ‘Let him go.’ It turns out my interpreter’s father was high up in the military.

Meanwhile, they were holding the plane; the director wouldn't let them close the door. I got on the plane, and boy we had a few vodkas on the way back to Budapest!

Man, I want to tell you, that was the one time I was really, really scared. I thought it was over then, I really did.

We finished the movie in Budapest, and I volunteered to go back into Istanbul to record sound, because that city made sounds I’d never heard. The loudspeakers, the prayer chants — the noise of that city was just different and perfect for our movie. And the American producers freaked out. They said, ‘You can’t go back, you're in the computer!’ And an attorney said, ‘He can go back. If he’s in the computer, they just wont let him in!’

So I took my wife and I went back. I hired a bodyguard for her and a driver for me, and I recorded sound for three days. Shipped it back to London, and we went on to a holiday on the Greek island of Crete.

That’s what I do. Ski the deep powder, jump off the cliff, ski out of bounds — that kind of stuff. The movie got a CableACE nomination for cinematography.

The thrill for me now is working with a young director, or first-time director. There was a playwright and stage director who got an opportunity to direct a little movie in Chicago, and I got hired before I ever met him. The studio hired me so I would work with him to make sure he had a movie, which meant they would have a movie.

It’s a Sunday morning and I’m skiing in Deer Valley, Utah, and I have my phone headset on. The phone rings, and I thought it was this woman I was going to ski with that day. I pull off in the snow, out of breath, breathing hard, and the director says, ‘You want to call me back later?’ And I said, ‘If I may. We have a lot to talk about.’

I called him back that afternoon and he said, ‘I guess the studio told you that I don’t know what I’m doing.’ And I said, ‘Yes, sir, they did. But I know better. You know script, clearly, and you know how to handle the cast — considering your experience with the theater. The only thing you don't know is the technical stuff, and I do.’ He said, ‘Well, you’ll just have to teach me.’ And I said, ‘God bless you for admitting you don't know. Most young directors in this town are afraid to admit that.’ I didn't use the word ‘teach,’ but I offered to share with him what I knew. ‘But I don’t want to do it in front of people,’ I said. ‘I would prefer to do it privately. I suggest that you and I, on our own dime, meet in Chicago and we’ll go to the location.’

We basically had two locations for this little movie — two houses and a tree house in between. I said, ‘We’ll walk the script, we’ll play the parts, and I’ll show you two or three different ways we could stage and shoot it — so it will edit — and you can pick one. And that’ll get us started on day one. It doesn't mean we have to keep the same plan all day, but we have to get started, and we must start effectively. And on the tech scout, you're the leader. You have to know what you want, and then I can tell everybody how we’re going to do it. You have to describe your artistic intent here, what you visualize — your vision. My job is to deliver your vision, and that’s what I will do.’

The best professional advice I’ve received was from Allen Daviau. I called him from a location [before lighting] my first really big interior. I said, ‘Allen, I’m really nervous. He said, ‘Relax. Trust your artistic instinct, because you know a lot more than you think you know.’ I said, ‘Is that it?’ He said, ‘Oh, one more thing. Remember, you gotta put the first light somewhere.’ And he started laughing. He was great.

I also learned from Peter James to take chances. ‘Don't be afraid to take some chances,’ he said.

I did make another memorable blunder. I was introduced to Steve Tisch in Aspen, Colorado, at a Christmas Party; I think it was 1992. He’s a big-league producer now — he’s an owner of the New York Giants football team — and he asked me to shoot two pilots for him on videotape. And I said I wasn’t available. I just didn’t want to do videotape. Huge mistake. Huge.

He never gave me the names — he just said two pilots. I really was booked, but I could have gotten out of it. Had I had my senses about me, if my ego was in check... But I just said, ‘I don’t shoot video — I shoot film!’ Two pilots. That was a blunder.

My first time shooting digital was around 15 years later. It was a small movie that I did in Tennessee for a friend. He picked the cameras, because the producer wanted to use his own, and I picked the lenses. We shot with a Canon [EOS] 5D Mark II, I got some primes from Otto [Nemenz], and we made a beautiful movie. I was really surprised.

I’m a big fan of the sculpture of Dave McGary, out of Santa Fe, New Mexico. I’m also influenced by Edward Hopper, and, of course, James Hurrell. [Hurrell’s paintings are] hanging on Panavision’s wall, and at EFilm. It’s like an art show over there.

I’m always studying light and shadow. If I go through the Louvre Museum in Paris, there’s one artist, I cannot remember his name, but his color for moonlight is something I’ve duplicated.

When I got to Amsterdam [for a production], I got off the plane and the director took me to the Rijksmuseum, and we went up to look at six Vermeers hanging on the wall, and he said, ‘This is what I want my movie to look like.’ And I said, ‘You’re kidding. You realize this Vermeer fella had a lifetime to do this — I’ve got 45 minutes!’

And there’s also a modern-day artist named Graham Knuttel, out of Dublin, that few know about. I’m told [Sylvester] Stallone collects his work. I only have one. I also have art books — Eisenstaedt and all that.

I’m influenced by new material, whatever I see next that captures my eye.

In terms of genres, I’ve tried most everything — but I really would like to do a gritty Western. I’d like to do My Darling Clementine again. There’s a sequence in that movie where they used infrared film for day-for-night — some big ‘Scope night stuff. I think I’m going to be doing a movie in Texas; it’s a big exterior movie and a lot of it is at night, and we’re going to have to do day-for-night. I’m trying to talk the director into not shooting digital, so that I can do the day-for-night with infrared black-and-white film.

If I weren’t a cinematographer, I’d be a downhill racer and a sculptor. I love to snow ski — even at my age, I ski way too fast. Every time I put on my skis or get on my Harley, I ask myself, ‘Is this the day you die because you do something stupid?’ Then I flash on that machine gun in my face at Ataturk Airport, Istanbul!

The ASC simply commands respect. It's such an honor — I can’t adequately describe it. I’m thrilled to be a part of it. I go through the front doors of the ASC Clubhouse and I feel, ’Do I really belong to this group?’ I have to psychologically pinch myself when I look at the pictures on the wall of all these phenomenal cinematographers.

The reason I’m in the Society is Allen Daviau called me up one day and said, ‘With your body of work, you have now qualified yourself for submission to the ASC. I’m going to sponsor you.’ I said, ‘Really?!’ I had never even considered the possibility of it. It was out of the blue — [ASC members] Allen Daviau, Ralf Bode and Charlie Correll signed my paperwork. I went in for the interview, and I was just terrified. I thought, the guys asking me questions are going to have 35 Oscars — or [at least] five — and this is going to be awful, and I’m going to embarrass myself. It’s terrifying. But now I’m sitting in on new members when we interview them, and I’m feeling their angst. I really feel for them, because it's like your heart’s leaping out of your chest. You’re so nervous you can barely speak.

A great moment for me was after I got in the ASC and we had the first party — I hadn’t seen Laszlo Kovacs in a couple of years, and he said, ‘Congratulations. You're now a force in the industry.’ I said, ‘Wow, a force in the industry. Naw, it can't be.’

Andrew Fish is the managing editor of American Cinematographer.