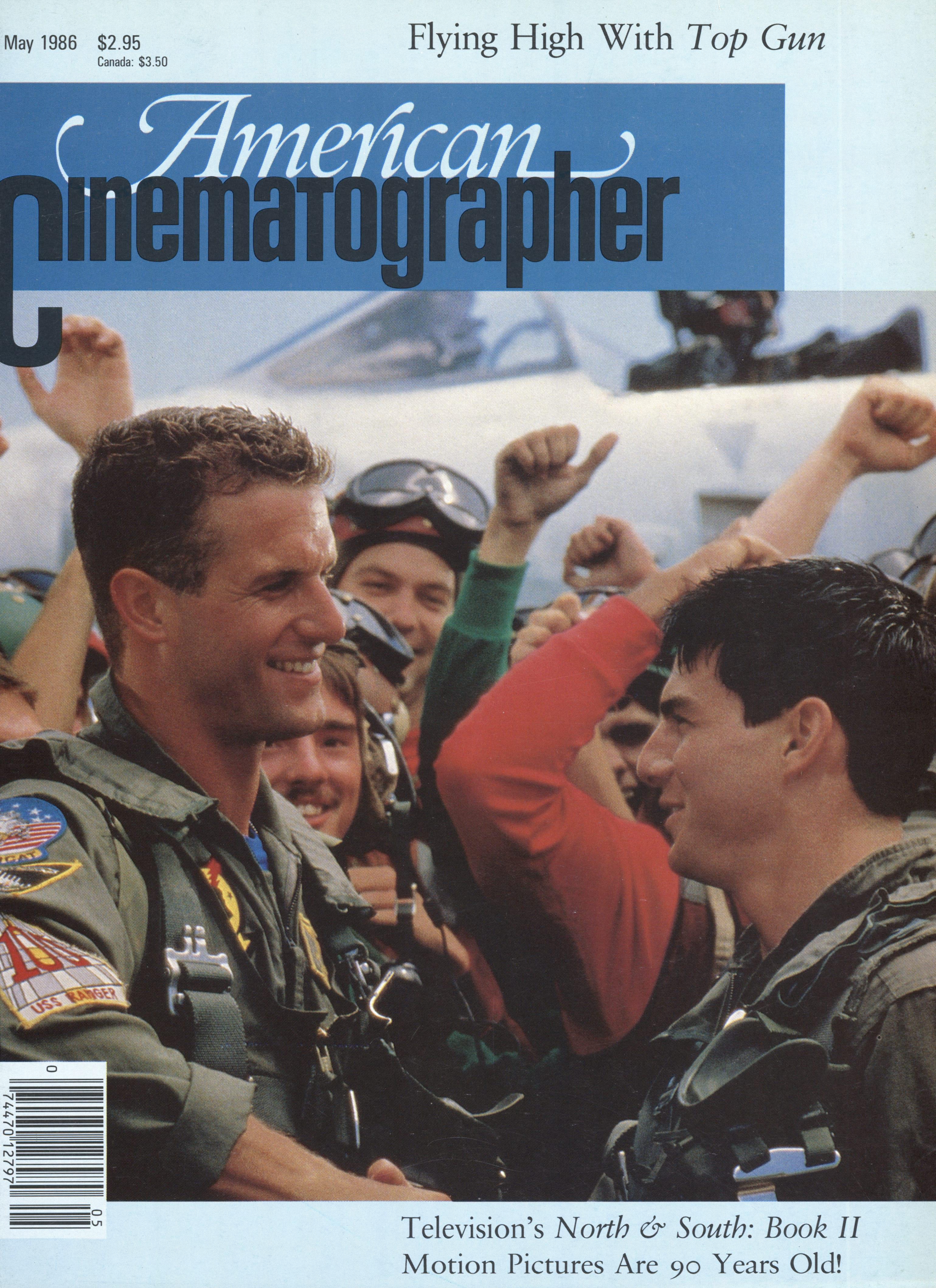

Flying High With Top Gun

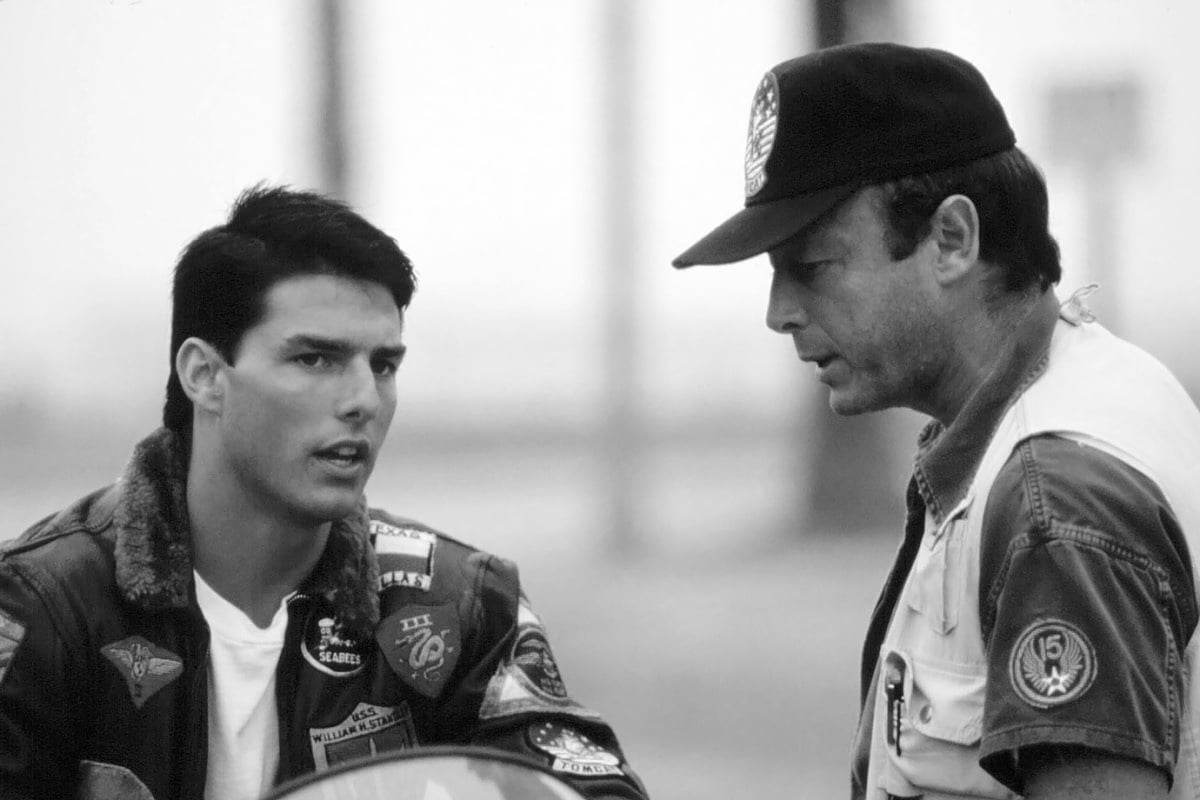

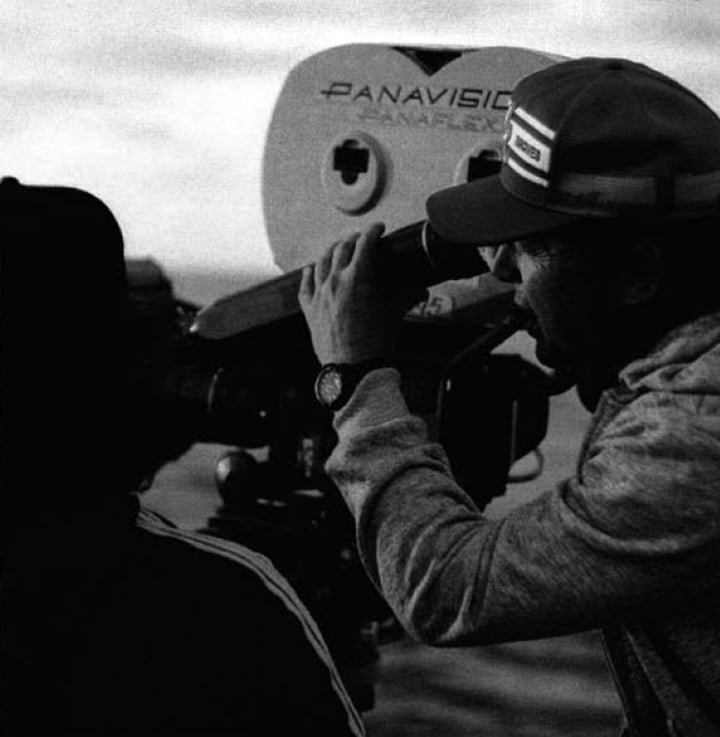

Director Tony Scott, cinematographer Jeffrey L. Kimball and other key collaborators capture dramatic aerial action.

By Les Paul Robley

It is midday aboard aircraft carrier U.S.S. Enterprise. A pilot, dressed in full flight regalia with a helmet tucked under his arm, strides toward a silver, metallic eagle, cooking and shimmering in waves of rising heat. Like a knight preparing to mount his white steed, the pilot rechecks his gear and aircraft, securing his articles of war that are currently being used as implements for peace-keeping and military readiness. All about him hovers a ceaseless ear-splitting scream, an earth-shaking thunder as an adjacent F-14 Tomcat begins its ascent into the vast blue ocean of clouds and eternal wind. As the sound ebbs and the aircraft climbs 2,000 feet, all that’s left is a trail of white fumes and two glowing pink after-burners, a fading memory of the depth of man’s longing to soar like the eagles.

The pilot is a member of Top Gun, the Navy’s prestigious Fighter Weapons School, training ground for the boldest, brightest and toughest naval air pilots in the world. He is of a different breed - competitive, courageous, totally committed to achieving excellence in his chosen career.

It is said that when a Top Gun pilot slips into the cockpit of an F-14 for his first flights, the U.S. Navy has already invested a million dollars in his training.

The objective of the Top Gun program is to identify the Navy’s best pilots. Since its inception in 1968, the school grew directly out of the United States’ experiences in Vietnam. During the first years of the war, the kill ratio was three enemy planes (MIGs) shot down for every one American plane destroyed. (During Korea, the average had been 17 to 1 and in World War II, 15 to 1.)

This unsettling news led to the Navy’s 1968 recommendation that a fighter pilot training program be created. The program was dubbed “Top Gun,” the name of an annual air-to-air gun competition held by various armed services in the 1940’s and ’50s

The results of this intensive training in air combat maneuvering (ACM) were dramatic. When Top Gun graduates returned to the second half of the Vietnam War, the Navy’s kill ratio zoomed to 12 to 1.

In May of 1983, the latter half of one of Hollywood’s hottest producing teams, Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer, chanced upon an article in California Magazine. Entitled “Top Guns,” it was a detailed look at the school and the quest for excellence in the pilots who attend it.

“Not only did we like the title and strong aerial photography, but we were attracted to this uncommon environment, with its own terminology and its bigger-than-life characters,” says Bruckheimer. The two of them instantly saw a movie.

Upon optioning the story, Simpson and Bruckheimer hired writers Jim Cash and Jack Epps, Jr. to fashion a screenplay around the material. They had already sold the idea to Paramount by means of a simple few-line pitch, plus their mega-hit movie track record, led by Flashdance and Beverly Hills Cop. But before they could continue much further, they realized that without the cooperation of the Navy, Top Gun might never get off the ground.

“It was obvious that we would need the full cooperation of the Navy in order to achieve the authenticity that was crucial to our story.”

— producer Don Simpson

Simpson, unfortunately, had sour dealings previously with the Navy over the film An Officer and a Gentleman. The Navy had considered the subject matter “profane” and “irreverent.” So, anxious to set the record straight and show the positive aspects of Naval training, he and Bruckheimer flew to Washington, D.C. and presented their proposal to top brass at the Pentagon.

“It was obvious that we would need the full cooperation of the Navy in order to achieve the authenticity that was crucial to our story,” recalled Simpson. “Not only was the Navy 100 percent receptive to our plans, but they suggested a technical adviser, a former Top Gun instructor, Capt. Pete Pettigrew, who lived in Southern California and eventually became a key member of our team.”

The Navy’s only condition was that the filmmakers be thoroughly accurate and portray the students’ commitment to the military and its lifestyle. With that agreed, writer Jack Epps traveled to Naval Air Station Miramar, the largest master jet air station in the world. Covering nearly 24,000 acres in San Diego, NAS Miramar has all the characteristics of a self-sufficient city.

“What it boils down to is to try to do something visually that’s a little out of the ordinary. To try to coax some texture and imagination out of the film, finding an impression that evokes an emotional response from the audience.”

— cinematographer Jeffrey L. Kimball

Epps attended declassified Top Gun classes, flew an “alpha strike” in the backseat of an F-14, and researched the attitudes of the young pilots who serve as students or instructors at the famous school. Unfortunately, the initial draft of the script was rejected by the Navy since too many “accidents” were depicted.

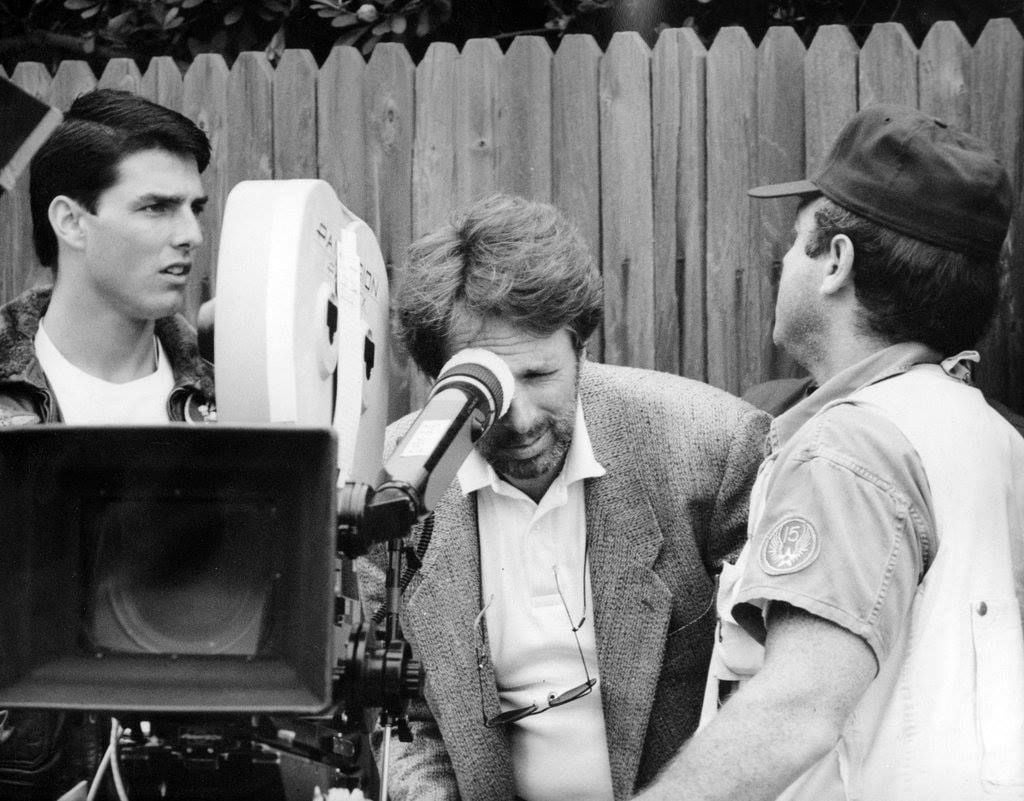

For a $13 million picture of this caliber, the “look” would obviously be very important to its success and appeal. The producers needed a director with a strong visual style in order to pull it off. They found their answer in British-born TV commercial director Tony Scott (brother of visual master Ridley Scott). The two brothers were partners in a commercial production company and had won virtually every major award in the field.

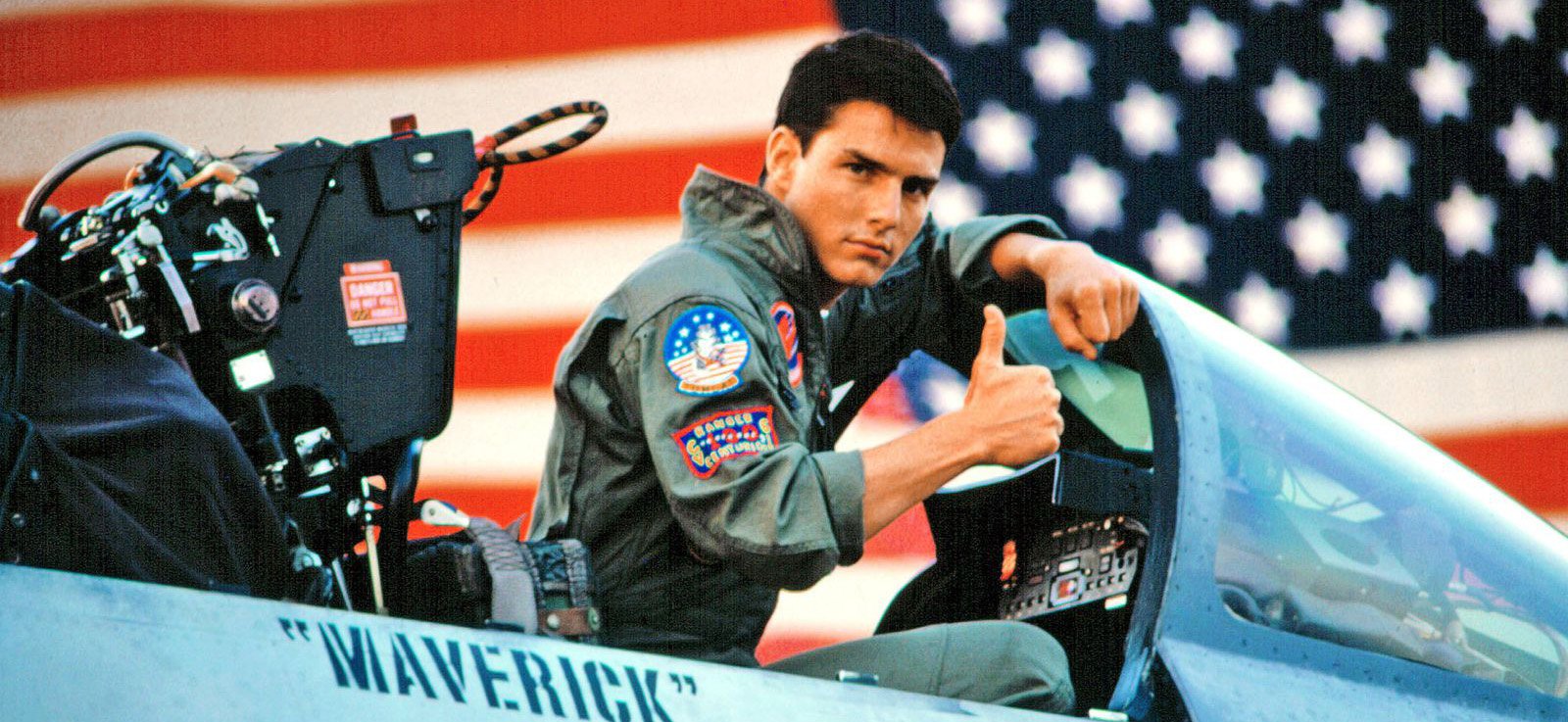

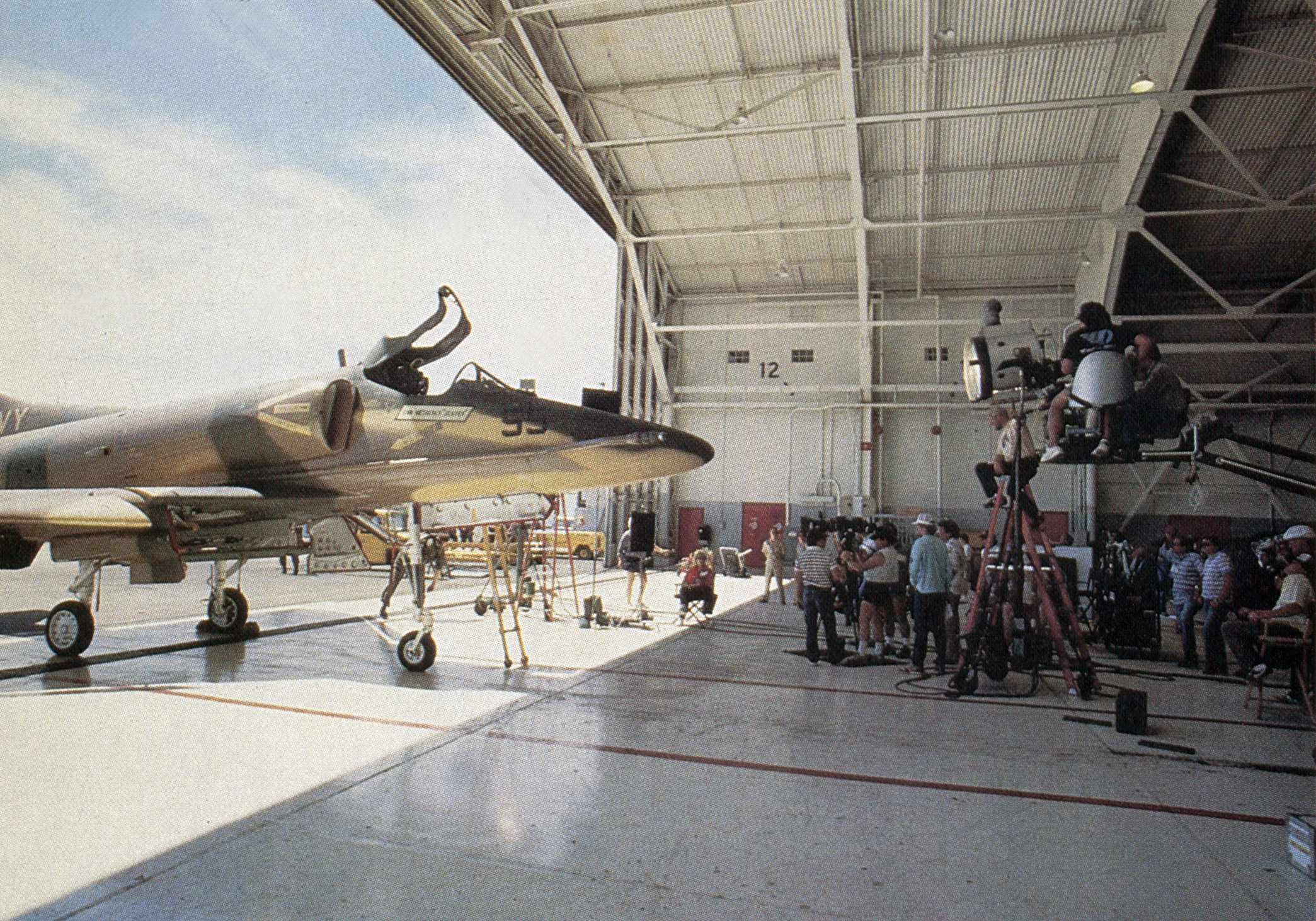

The film stars Tom Cruise as Top Gun pilot Ft. Pete “Maverick” Mitchell, and Kelly McGillis from Witness. But the real “stars” may be the $36 million F-14 Tomcats, F-5 Tigers and A-4 Skyhawks which constitute the world of “yanking and banking” during Top Gun's dazzling aerial scenes. Unlike The Right Stuff, which relied to a great extent on miniatures, Top Gun shows audiences “the real thing,” shot aboard aircraft carriers U.S.S. Ranger and U.S.S. Enterprise, at Naval Air Base Miramar, and inside moving F-14 and F-5 cockpits flown by actual Top Gun pilots. Only a few scenes are achieved via special effects.

Producer Jerry Bruckheimer chose cinematographer Jeffrey L. Kimball to create this world, based on his slick second-unit photography for Bruckheimer’s remake of The Cat People, and on commercials (where he had collaborated with Tony and Ridley Scott). Before Top Gun, Kimball’s previous film credit was The Legend of Billie Jean.

Reared in Dallas, Kimball attended North Texas State University in Denton, where he studied radio and TV. He had always wanted to be a filmmaker ever since the 8mm shorts he made in high school.

Fresh out of college, he got a job working for Warner Brothers as a distribution trainee in 1965. But he still wasn’t on the backlot. So, after six months, he quit to become an apprentice to Bill Fangley, a Hollywood commercial still photographer of the 1930s and ’40s. Fangley was 75 at the time and needed someone to focus the camera, light his cigars and drive him around. Kimball spent four years with the old mentor and learned so much about the subtleties of lighting that he credits Fangley with giving him his first leg up in the industry.

In the late 1960s, Kimball worked on many low-budget AIP films. He also had a great deal of success with European directors, such as Ridley and Tony Scott. “One night I was watching one of those old AIP films I had worked on,” Kimball recalled. “It was technically bad, but it was so early on in my career that I could see some very daring things which, of course, came out of ignorance, but were still so free and loose. That inspired me and I told myself I wanted that imaginative part back. I had the technical expertise to make it happen. That’s when I really began to have fun with my craft.

“Essentially, what it boils down to is to try to do something visually that’s a little out of the ordinary. To try to coax some texture and imagination out of the film, finding an impression that evokes an emotional response from the audience. If I can look at something and have it leave me with a feeling or impression, hopefully, it’ll do that for the audience too.”

Top Gun is a picture of high-energy and high-tech hardware. Kimball and Scott first approached the photography by spending a great deal of time looking at two earlier pictures of similar subject matter: The Right Stuff and The Final Countdown.

“Tony and I had experimented on commercials using colored graduates and other things considered unusual a few years back — things we take for granted today, such as altered skies and different perceptions of reality. Back then we always tried to press the limits to do something new. We pooled all the glass and filters we’d collected over the years and tried to design a different look.”

Filming commenced on June 26, 1985 in Oceanside, California, later moving to Miramar for several weeks to begin the scenes which involved an impressive line-up of F-14 Tomcats, F-5 Tigers and A-4 Skyhawks. Flight suits and helmets were designed to maximize visual appeal and plans were made to customize the aircraft.

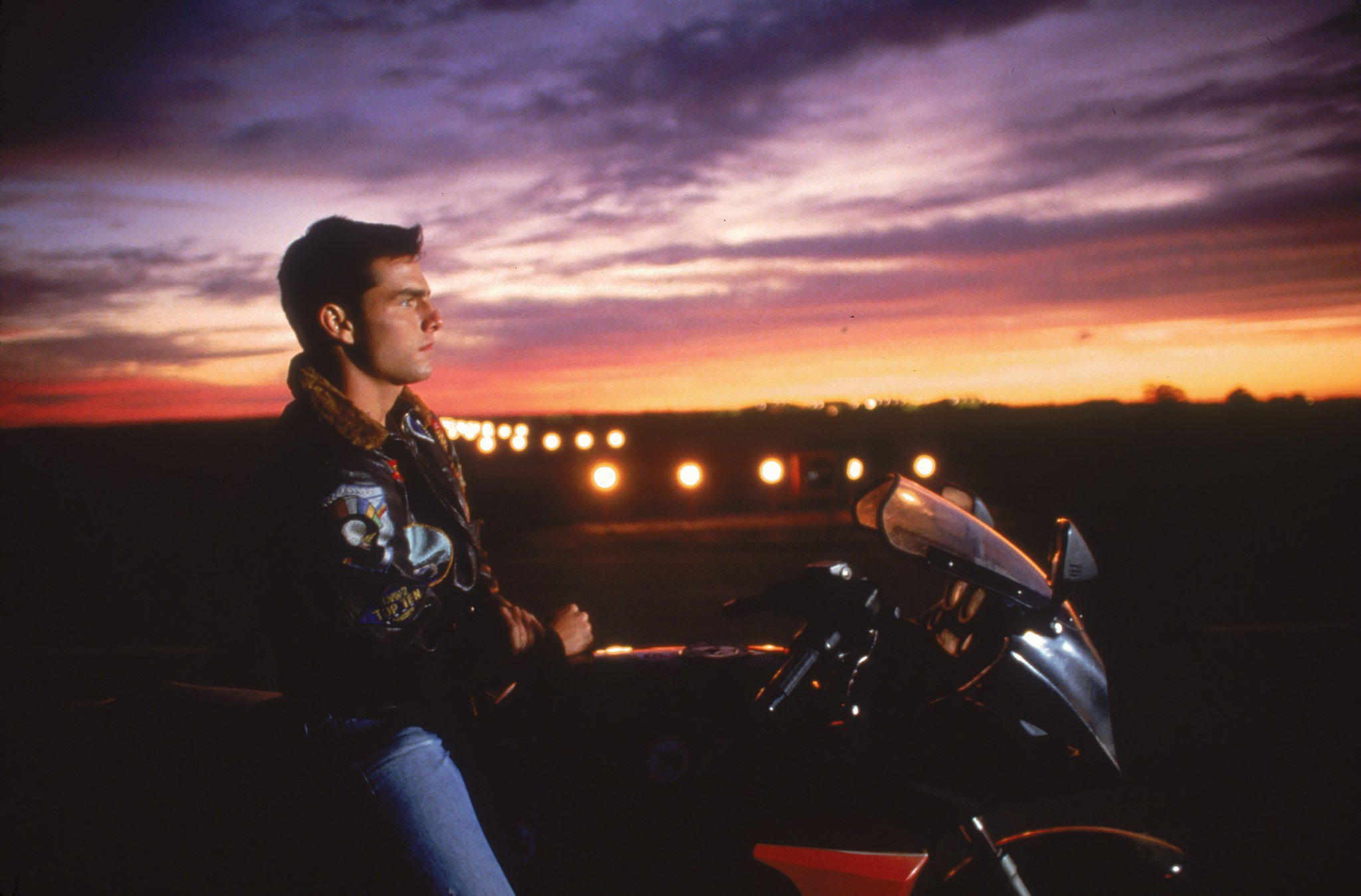

Here the filmmakers sought to portray a feeling as in a medieval drama — like knights in shining armor. They decided to shoot slightly off-speed (about 28 frames-per-second) to achieve the altered, weighty perception of reality experienced on deck. They even shot dialogue at 28 fps.

“There’s a bizarre feeling of unreality when you’re there,” remembered Kimball. “Your senses become muffled. You get off the jet and you have your helmet on, your inflatable flight jacket, your eyes and ears are covered by goggles and earmuffs, and there’s a tireless 30-knot wind whipping across the deck. Less than 100 yards away, 50,000-pound jets slam every 10 seconds onto a football field length of black and white parking lot doing 180 mph. A ceaseless, pounding sound...

“I couldn’t help but attempt to convey that feeling some way in the film. The roar of the F-14 is awesome, deafening. The only way we could communicate was through different kinds of sign language. Your life depends on these signals. In a real sense, it’s a life-threatening situation on these carriers, and the Navy’s really good at it. They spend their time launching and recovering planes all night long. If war started tomorrow, it wouldn’t really change their day that much.”

Into this well-ordered chaos came the group of Hollywood neophytes. The crew attended briefings about daily working procedures. Few were able to sleep amid the ear-shattering noise, and many spent their time on deck simply watching the takeoffs and landings. Because the ship operated on round-the-clock shifts, there was really no sense of day or night, a disorienting factor for everyone involved. Actor Rick Rossovich became so lost one evening by the maze of hallways that he finally gave up, catching a few hours’ shut eye on a mattress left in an empty hall.

The carrier proved to be no ordinary shooting location by any means.

Temperatures on the flight line sometimes reached a boiling 110 degrees, and the thundering jet noise frequently halted filming. Scott recalled: “That noise could really scramble your brains. It was sometimes hard for an actor to remember his lines with the roar of an F-14's afterburners behind him.”

How did soundman Bill Kaplan, deal with the incessant noise? “We turned him loose and shot mostly wild,” answered Kimball. “We had some quiet window periods when they were cleaning the deck at sun-up. There wasn’t much air traffic for a few hours so we’d be out there bright and early shooting the dialog during those holes of quiet. But the continuous ambiance will be what makes our film appear more realistic.”

The company encountered several other obstacles, not the least of which was the “schlepping” of heavy film equipment up and down 12 flights of narrow stairwells. Kimball told an amusing story about how the crew often borrowed a small private elevator that the top brass and VIPs used to get from one deck to another. One day an admiral came on board, and when he opened the door to his elevator, found it loaded with movie lights, tape and three grim-faced grips. “He had to walk up the 12 flights to the deck and was pretty hot by the time he got to the top,” laughed Kimball. “So, that ended our elevator use."

“Everything presented its own challenge. Inside the aircraft carrier there are many two-foot fluorescents. We did our best to make these look authentic.”

Scott and Kimball met each evening with the ship’s navigator to plan the sun time for the following day’s shoot. Explained Kimball: “Every set-up was based on the real available light level. We brought the light in from the outside using arcs. Inside we used Duarcs for fills. The texture of these arc lights is very much like a daylight feel. We chased that available look every step of the way. No incandescence was used save for the later process stage work.”

Next came one of the most difficult scenes in the movie. When Maverick and Iceman (Val Kilmer) are in the air competing, Maverick’s jet gets caught in the turbulence of Ice’s plane and goes into a spin over the ocean. He and his radar intercept officer, Et. Goose Bradshaw (Anthony Edwards), must eject into the choppy sea.

Tom Cruise and Tony Edwards had to spend two rigorous days in chilling ocean water to film the air-sea rescue. “We encountered all the usual problems that you’d have working in the ocean with the boat going one way, the helicopter going another and the actors in freezing water,” said Kimball. “At one point Cruise got tangled up in his parachute strings — he did his own stuntwork here — so the scuba divers had to fish him out. There are a lot of dangerous elements in this film and everyone had to rely on quick reflexes.”

Kimball used Panavision equipment to shoot the ground and boat action. There weren’t many backup cameras employed — just the A and B cameras. Steadicam was used for scenes of the pilots running toward their planes. Joe Valentine contributed to the superb long lens work on the carrier deck. At the end of a day’s shooting, first assistant Kenny Nishino had to do major clean-up jobs on the equipment, what with all the salt in the air. Shooting on the carrier was often a touch-and-go situation due to the inability at times to get the aircraft free for filming.

Choreographed by Scott, aerial coordinator Dick Stevens and Top Gun commander Bob Willard, the extremely complex dogfighting maneuvers were flown by actual Top Gun instructors and pilots based at Miramar.

Pilot Clay Lacy employed his Astrovision process to film these sequences. It involved his Lear jet rigged with a kind of snorkel camera system, which enabled him to fly alongside and film another plane. An Arri-3 was mounted to a periscope that protruded through the top and bottom of the jet. (Continental Camera placed Astrovision in Lacy’s Lear.) David Knoll was operator for Astrovision and Greg Schmidt was aerial assistant for half the picture. John Connors and Jim Connell were operators for the ground story filming.

Dick Stevens served as technical engineer and liaison with Grumman Aerospace (builders of the F-14) and the military for the mounted cameras inside the cockpits. “We used cameramen from the Air Force to shoot from the back seat, but 90 percent of it was shot by Lacy using the Astrovision System,” admitted Stevens. “Manager Bill Badalato and Tony Scott hired us because of our experience with the military in photographing contemporary high-powered jets. They simply told us: ‘Your job is... get the damn planes on the screen.’ So we worked closely with Lacy to schedule his entry during the filming, and pretty much put together the entire systems selecting package.”

Special instrument “military” cameras from Photosonics were selected over Panavision due to the restricted space within the cockpits. Six other cameras were mounted externally and operated by the pilot. Since normal camera mounts were not engineered to take the kind of stress found in an F-14, Stevens and associate Tom Harman had to design modifications to the interiors of the aircraft. These designs were then okayed by the aircraft manufacturer and the Navy to be sure they passed engineering and safety specifications.

“We killed ourselves to obtain Navy clearance,” Stevens added. “Anytime you touch a military aircraft you must have the Navy approve structural analysis. They’re not going to let Hollywood come in and do a jerry-rigged job.”

The F-14 Tomcat is the U.S. Navy’s supreme fighting machine. Costing $36 million each, it can climb 30,000 feet in one minute, fly faster than Mach 2 and haul seven tons of weaponry. Safety was vital to Paramount Studios since they could go belly up if one of these planes went belly under.

“First we interfaced with Grumman to review systems they had built for The Final Countdown,'" said Stevens. “These included six external mounts on the F-14 with a camera pod housing. In addition to the existing positions they had created for their own operational analysis and for Final Countdown, we collaborated with them to design mount positions in the cockpit for two 35mm cameras.”

He and Harman equipped cameras in both the front pilot’s cockpit and the rear RIO’s position. Both cameras were mounted facing aft, aimed at the pilots. Each set of mounts went exclusively with that aircraft for the entire shoot. Each was modified and completely rewired by Grumman. They installed discreet circuits for the camera mounts throughout the aircraft, internally and externally.

The cameras employed 200' magazines with 18mm, 35mm and even 50mm Nikon lenses. This was the smallest condensed package that the F-14 interiors could accommodate. The two-minute film loads meant the pilot only had one pop at a time. The camera angles and f-stops were all predetermined and set by Stevens, Scott and Kimball. This was the first time 35mm had flown inside an F-14. The military is still keen on using 16mm.

Four camera stations were mounted externally: one on the left-wing pylon or bomb rack, one in the Marcelle position attached to the fuselage on the underbelly, one on the right-wing faring position at the top dorsal, and one above the wing just behind the cockpit. Each camera could look forward or aft on the mount. The trigger switch was operated by the pilot from the cockpit position.

According to Stevens, two internal cockpit cameras and one selected external mount were the most that could be triggered electronically. Once airborne there was no ability to track. The camera angle was restricted to a preselected position, focused on a different angle of the pilot. This was later reset for each new mission. The pre-determined f-stop was tricky to calculate, especially when the aircraft changed position in the sky relative to the sun.

“The dogfights were all carefully choreographed to tell the story,” said Kimball. “We’d have a briefing with the Top Gun pilots and go over the various maneuvers. They’d put them on a card and then go out and perform them for one-and-a-half hours, until they ran out of gas.”

The film company had decided to shoot the film in the Super 35mm format. This is a 2:35 to 1 aspect ratio that incorporates flat, spherical lenses, using the full (silent) aperture including the soundtrack area outside academy aperture. It is fast becoming more and more popular among the film community as an alternative to using anamorphic lenses. The extra .112 inches provides a larger copy ratio with more film information space when making release prints. This technique is employed often in process work when shooting background plates.

The reasons for not using anamorphic on Top Gun were many. The most important had to do with the tremendous physical stress which the cameras and lens systems underwent when mounted to an F-14. There are approximately six Gs of pressure when the aircraft banks a corner. “We thought of going anamorphic on the picture because Tony insisted on the 2:35 widescreen look, since it better accommodated the window configurations seen from inside most cockpits,” Kimball recalled. “But then we would have had to start mixing the formats up heavily. The stresses in the aircraft and the added weight and mass of anamorphic equipment create more inertia. A five-pound lens begins to weigh 100 pounds when turning a corner.”

Shooting with spherical lenses meant not having to deal with an extra piece of anamorphic glass, extreme nodal point shifts, or focusing problems. Spherical lenses are sharper with better depth of field and less light loss. But Kimball was quick to point out that spherical does not necessarily mean better or worse. “Rather, it’s different,” he indicated. “It’s almost as if the quality of the lens gives a different feeling of presence. A spherical lens certainly has different aspects than an anamorphic. It alters your style, depending on what equipment you’re working with, just as a Canon does against a Nikon or a Panavision.

“The anamorphic lens will press you to light or tailor the way you set up your shot. The same goes for Super 35. It’s a different animal. You compose for it differently, even though the aspect ratios are the same. Shooting it offers different problems in composition and mood. The difference in f-stop or depth of field gives you varied impressions of how you’d approach it.”

Kimball protected for TV by composing for 1.66 as well. Each of the Panavision and Arriflex lens mounts had to be optically centered for full aperture by changing the mounting plate on the camera’s front. The instrument cameras on the F-14s were already equipped with a full aperture-centered lens axis.

The Panavision system utilizes a common top line, extracting the picture from the top down. Therefore, headroom always stays the same for 70mm, 35mm, and even TV. Kimball wanted to avoid using a common top line because of all the different camera systems employed on the shoot. He elected to extract the 2.35 picture frame from the center 2 perfs off the normal 4-perf pull-down.

When the release prints were to be made, Kimball wanted to re-silver the film. He pointed out that another film photographed in Super 35 and re-silvered was Silverado (no pun intended). MGM Labs calls their process “upper-scale enhancement.”

According to Kimball, the lab runs the film back through a D-76 developer which enriches the blacks.

Obviously, release prints in Super 35 are grainier than normal anamorphic prints. This is because the center 2-perf portion of the original negative is the only part used. “I was concerned about grain which is why we wanted to resilver the film,” said Kimball. “We did a lot of testing before we used it. It costs extra to re-silver these prints, but I feel it’s extremely important to do it because in the blow-up we’ll pick up extra grain due to the diminished negative size. And to view this film in 2:35 is so much more dramatic than 1:85.”

Kimball selected two film stocks: 5247 and 5394. “I love 47 because it has finer grain and more contrast,” he continued. Kimball rated the 47 at 125 El and the 94 at 360 El. “The 94 has a look all its own,” he said, “perfect for the gritty feeling we wanted. It’s very helpful in low-light conditions. I’m not sure everyone will like it. It’s got a little broader stroke to it. The 94 tends to have a little more grain but it’s not something that bothers me, so long as you can play your lights and darks in such a way that the feeling is there. I’ve seen some lovely stuff shot with 94 and it’s becoming more and more popular all the time. I think the stocks should mesh together pretty well to the point where the average moviegoer won’t be able to tell the difference between the two.”

The gritty nature of the stock was nicely complemented by the use of polarizers for shots of the planes. The actual steel resembles titanium painted gray with small panels and tiles all over the body.

“Sometimes I’d look at these airplanes and they’d almost seem like starships out of Star Wars," Kimball remarked. “We sucked the reflections out with the polarizers so the jets took on a hard, matted sheen — sort of like a dull armor.

“You don’t know the meaning of the word speed until you see a 50,000-pound jet streak toward you at 300 mph.”

Phase 4 of the production saw the crew move to the naval air station in Fallon, Nevada for filming ground-to-air sequences as well as more air-to-air. Twenty pilots participated in these scenes, which were filmed with an elaborate tracking system owned by the Air Force.

The tracker is an electronic Cine Sextant system of the Instrument Marketing Group (formerly Photosonics) which ignites up to eight instrument cameras. Top Gun used only six. A large turret on wheels, modified directly from a howitzer mount, the tracker consists of a rack of cameras that can turn 360 degrees. The cameras are equipped with extreme telephoto lenses (up to 4800mm). The system is used by the military principally to track missile and weapons systems into outer space.

Scott and Kimball scouted a number of locations before finding a marvelous 400' precipice that hung over a tremendous sink. The spectacular rock pinnacles in the background may become famous once the film is released in May.

The tracker was flown by helicopter almost to the top of the precipice, while the crew established a base camp at the bottom. The Air Force operator couldn’t afford to let the expensive piece of government equipment be hauled all the way up to the crow’s nest. The tracker was situated looking out over the valley using the sky as a backdrop. The 4,000-foot drop enabled the jets to perform maneuvers level with the cameras, while three operators tracked them from the ground. They photographed the F-14s zooming up from below and darting between the rocky pinnacles, obtaining some startling footage.

“They’d beeline straight toward us and swoop right over our heads,” said Kimball. You don’t know the meaning of the word speed until you see a 50,000-pound jet streak toward you at 300 mph. You really don’t achieve a true sense of how fast they fly when you’re moving alongside them air-to-air. But when you’re static shooting with a 1600mm lens, and the object comes straight at you, you get an incredible sense of how fast they really travel.”

In order for the aircraft to align themselves on the mountaintop, the crew flashed survival mirrors. One of these mirrors later came in handy when Scott was out scouting locations in his car at sunset. Kimball and a pilot were looking for him from a helicopter and by chance happened to see his survival mirror flashing on the desert floor.

“We tried making the skies very blue and more interesting by using Harrison sunset graduates,” Kimball noted. “We always had our formidable collection of glass on hand if we wanted it. We had made a number of tests previously on commercials, so we knew what to expect.”

Jack Cooperman, ASC photographed both above the surface (from a helicopter) and undersea during the air-sea rescue sequence. “We were able to exaggerate the sunset with filters,” Cooperman said. “The wide shots really worked well, with the filters set for the horizon. Actually, we created sunsets in the camera.”

A very real-looking special effect — real, because it actually exists — was the Miramar TACTS Trailer. A highly sophisticated computer link-up records the pilot’s air combat maneuvers on video, allowing them to re-examine their dogfights at a later date. The pilot types in the command and receives whatever view of the encounter he wants.

The TACTS Trailer resembles a big rear-projected, two-color vector writer. Some might compare it to a giant video game. Unfortunately, the computer graphics run out of phase with 24 fps cameras.

To alleviate this problem, Kimball filmed the graphic directly off the screen onto 35mm film running at 32 fps, employing a 144-degree shutter to eliminate flicker. He next transferred that to a 24-frame video. With the actors seated in the foreground, he ran the 3/4-inch videotape onto a rear-screen video beam projector. He recorded this composite in Super 35 with a Panavision camera running at the normal 24 fps. Thus, the same real-life video look was achieved, now in sync with the camera and sound equipment. Dick Clark was in charge of the video systems.

Kimball acknowledged the help of scores of people, without whose assistance Top Gun might never have flown. “The film’s not full of special effects; it’s full of reality,” he concluded. “I believe the film will feel very real when people see it. Everything was directed to give the sensation of actually being there, experiencing it.

“I hope audiences will come away with an impression of being involved in the subject matter and the photography, leaving them with an emotional response. If that happens, then we’ve done our job.”

Jeffrey L. Kimball would later re-team with Scott on the films Beverly Hills Cop II, Revenge and True Romance. He has been a member of the ASC since 1990.

Top Gun was recently remastered and re-released in 4K HDR for the film’s 35th anniversary. The sequel, Top Gun: Maverick — shot by Claudio Miranda, ASC — is scheduled for release in May of 2022.

Author Les Robley is a Los Angeles writer whose expertise is film with emphasis on special effects and animation.

AC Archive subscribers can access this entire issue, as well as more than 1,200 others. Subscribe here.