Future of Cinematography: Advances and Opportunities

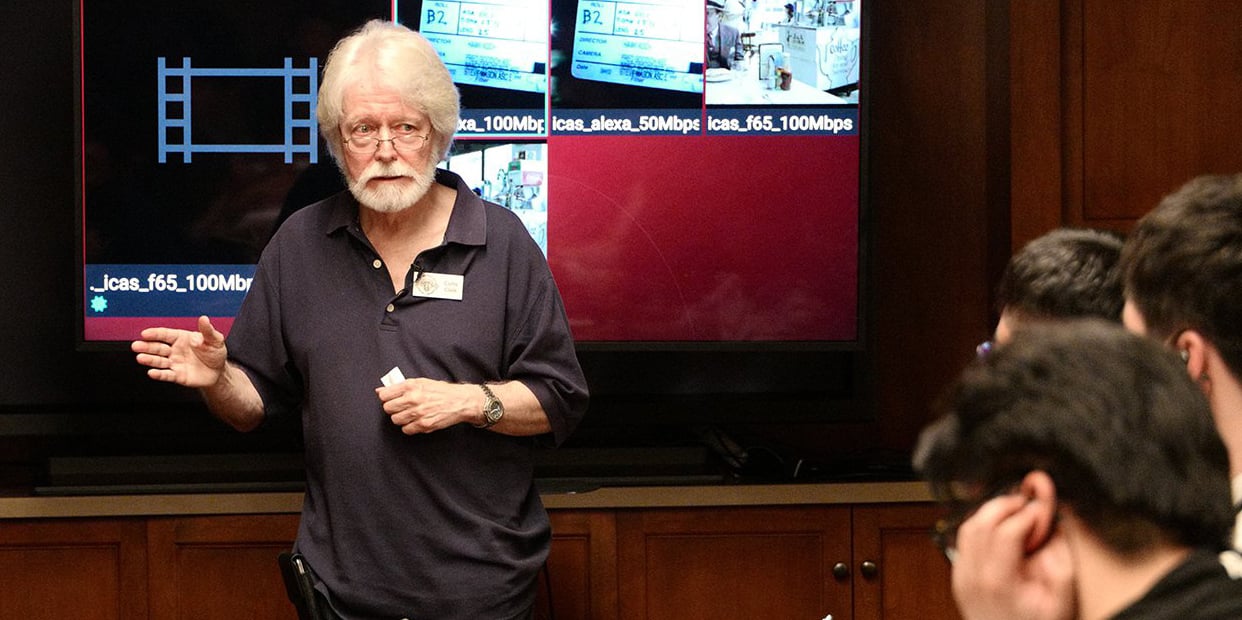

ASC Motion Imaging Technology Council Chair Curtis Clark, ASC on the state of the art and how to stay ahead of the curve.

“It’s imperative for cinematographers to maintain an understanding of new technology if we want to retain a creative edge,” says ASC Motion Imaging Technology Council Chair Curtis Clark, ASC, who has guided this body of cinematographers, postproduction experts and technologists since its founding in 2003. “That doesn’t mean one has to be an expert in everything, which is impossible, but having a working understanding of new methods and techniques allows one to be part of the creative discussion when new solutions are required. Look at our current situation: Everyone is looking for workflows to help get production up and running, and cinematographers are a key part of that. We should be prepared.”

Among other honors, Clark received the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences John A. Bonner Award in 2019 in recognition of extraordinary service to the industry. In tandem with his deep understanding of the latest technology, he is fascinated by the evolutionary past; his recent projects include producing the acclaimed TCM documentary Image Makers, about pioneering Hollywood cinematographers in the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s, who creatively employed the latest tools and techniques to establish the visual styles that continue to inform narrative filmmaking today.

Clark and his collaborators recently completed the 2020 edition of MITC‘s Progress Report, a sweeping, in-depth survey of advances in production and post technologies that is traditionally published in the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers’ Motion Imaging Journal. This created the perfect opportunity for Clark to discuss MITC’s latest findings and how they might impact the future of cinematography.

American Cinematographer: The Covid-19 production lockdown and global travel restrictions have many people talking about the virtual-production techniques used on The Mandalorian [AC Feb. ’20], which are discussed in this year’s MITC report.

Curtis Clark, ASC: The advances in that area have been impressive, and it’s the focus of our Joint Technology Committee on Virtual Production [a collaboration with the Visual Effects Society, the Art Directors Guild, the Producers Guild and International Cinematographers Guild Local 600, chaired by David Morin]. The Epic Games Unreal Engine, which drives the LCD-screen imagery, has progressed tremendously, and a new version of it will be released sometime next year that offers even more significant advancements. In the past, I’ve been fairly cautious about the virtual-production approach, but given the circumstances and the progress of the technology, I can foresee a time when these gaming engines will be able to create on set, in real time, a lot of the CG characters we see in movies today. That will allow cinematographers the chance to actively participate in their creation and appearance — how they interact with the lighting on set and are presented in the frame. Currently, all that work is done in post, and cinematographers typically don’t have the opportunity to participate in that process. I think our participation will go a long way in helping to enhance these kinds of characters, making them living, breathing participants in the story. The Virtual Production Field Guide, published this year by Epic Games, goes into great detail on this.

The ability to capture so much in camera — as opposed to shooting with blue- or greenscreens and comping backgrounds in later — would appeal to many cinematographers.

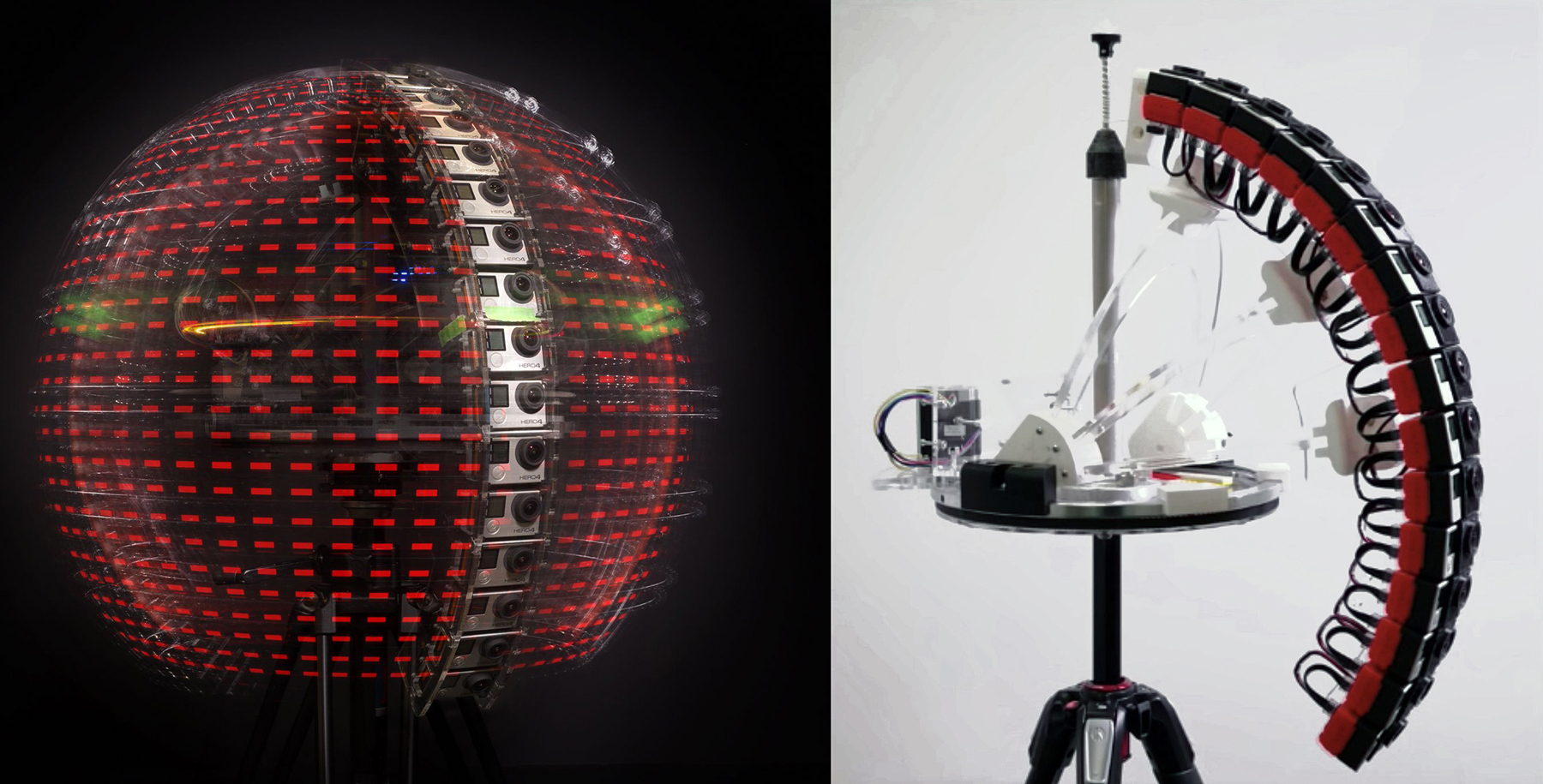

Of course, in part because everyone can immediately see an image through the lens that is very close to a final result — and because the backgrounds have to be captured or created in preproduction instead of in post, everyone on the team can agree upon what things will look like and make choices informed by that. So many times, a cinematographer will light and photograph a scene against a greenscreen with an understanding of what the background will later be, and then that background is completely changed in post, making the on-set lighting no longer appropriate and creating a result that doesn’t look quite right. Requiring backgrounds to be created and selected before a scene is shot will help erase that dilemma. It also opens up endless creative opportunities in terms of lighting, movement and compositions, which leads me to another technology, a controversial one, covered in the report this year: plenoptic — aka computational volumetric — cinematography, which employs a light-field camera. It’s definitely coming and will be a factor for cinematographers in the future.

The MITC report by the Computational Cinematography and Plenoptic Imaging Committee describes some of the recent advances in this area, particularly the research being done by Paul Debevec, the senior staff engineer at Google VR. Tell us more about that.

We’re lucky to have Pete Ludé co-chairing that committee with David Reisner. Pete is the president of the Immersive Digital Experiences Alliance, a nonprofit devoted to developing plenoptic cinematography by helping to set standards. He’s about as authoritative as anyone on the subject. Cinematographers have faced many challenges when it comes to oversight on image creation, but plenoptic cinematography will be our biggest. It’s a ‘You ain’t seen nothin’ yet’ moment. Because it records the characteristics of all light within a volumetric space, that data can be manipulated to alter the image in infinite ways. Where does that stop? Where and when will decisions be made, and who will make them?

ACES [the Academy Color Encoding System] was an attempt to get a handle on that issue vis-à-vis the DI process — to protect the creative intent and decisions made on set. Can you imagine something similar for plenoptic cinematography?

Absolutely, but this is a paradigm shift away from what we know today, a revolution in motion imaging. When you line up shots using this technology, you can later completely shift not only the lighting, but also the composition, the point of view; there’s no limit to what you can later do with the image. So what is the role of the cinematographer? We’re also dealing with 3D spatial relationships and different multi-perspective angles. How do you plan for that or previsualize it? It’s very difficult for some directors to make those decisions in preproduction and stay committed to them when so many other, unanticipated issues arise during production.

Over the past several decades, the need to make hard-and-fast decisions certainly seems to have decreased, in part thanks to new technology.

It’s true, but one of the things I find most interesting about virtual production is that it essentially goes back to a process we’re all familiar with, rear projection, which has been around for many decades. Yet it’s also interactive, allowing for real-time integration of elements in camera. It’s very effective, and having a background perspective that’s in perfect sync with the foreground and the camera movement adds an incredible degree of authenticity. And it’s only going to improve as we better integrate that with previs and 3D previs. So, being comfortable making on-set decisions that result in an image that’s very close to final — aside from the standard color tweaks and such — is going to have a huge impact. It’s combining the entire visual-effects process with the live-action production process, and that’s very exciting. If you don’t like what you’re seeing through the camera, you can change that on the spot instead of having to come back and reshoot something. This also speaks to cinematographers’ creative need to have a visceral connection to the images we’re creating. If we don’t have that connection, we’re just making a component to be used in another process, and that’s not really cinematography.

During World War II, movie audiences saw newsreels of combat footage from the front lines, which changed their perception of images. Handheld, poorly framed, out-of-focus and otherwise imperfect material was suddenly no longer ‘amateur,’ but ‘authentic,’ and those defects were adopted by filmmakers trying to depict realism. With the Covid shutdown, people are using a variety of video-conferencing systems to an extent we’ve never seen before. Might that eventually impact how we relate to images?

That’s an interesting comparison. I certainly feel like I’ve been on one endless Zoom call over the past few months, and it has been a lifeline. But the larger the number of people, the less effective it is. You don’t want a creative discussion to turn into a webinar. The experience illustrates that the technology needs to be improved if this is how we’ll be doing business in the future. It has to be as easy as a phone call. Many people have been using additional cameras to improve picture quality, as you don’t get much out of the typical laptop camera, so I see computer manufacturers greatly improving the quality of those just as they have with smartphones, many of which are now marketed primarily as cameras, even 4K cameras. A number of features have now been shot on iPhones, like Tangerine and Unsane. Adopting non-traditional tools for creative purposes is very interesting, as it offers new opportunities and choices. Might we someday see a feature shot mostly with a laptop? Possibly. Somebody might devise a very creative way to do that, and that would certainly be a product of our current situation, which is not going away soon.

A complete archive of MITC Progress Reports can be found in PDF form here. This year's report will be posted when available.

The Virtual Production Field Guide, written by frequent AC contributor Noah Kadner, can be found at here.