Face to Face: Gemini Man

A visit to the set of Gemini Man in Hungary, where Dion Beebe, ASC, ACS and a team of collaborators help director Ang Lee break new ground with a 120 fps 3D production co-starring a CG human.

Dion Beebe, ASC, ACS and a team of collaborators help director Ang Lee break new ground with this high-frame-rate 3D production co-starring a CG human.

Unit photography by Ben Rothstein, courtesy of Paramount Pictures.

Author’s Note: This post details my visit to the set of Gemini Man. A companion post on thefilmbook blog focuses on the creation of a virtual character for the film. This article is a revised version of the one that appears in the November 2019 edition of AC.

Directed by Ang Lee and featuring cinematography by Dion Beebe, ASC, ACS, Gemini Man tells the story of Henry, an elite assassin played by Will Smith, who is stalked by another assassin, Junior, who turns out to be a younger, cloned version of himself. The noir thriller is rife with action and adventure, but it also evokes the emotional, thought-provoking confrontation of an older man with his younger self.

The storyline provides a vehicle for two groundbreaking cinema technologies. Created in collaboration with Weta Digital, Junior is a landmark computer-generated character who is onscreen for almost half the movie. In addition, the feature’s unique format of 120 fps in 3D at 4K was realized with custom tools and workflows. Lee first pioneered this high-frame-rate camera technology on his preceding film, Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, with cinematographer John Toll, ASC.

AC was invited to visit the set of Gemini Man while the production was in Budapest, Hungary. The following account combines interviews conducted on set and during post-production with Lee, Beebe and a number of their close collaborators.

The Image

Let’s start with the image. During my visit, Lee invites me to watch dailies with the crew, seating me between him and Beebe. The lights go down, and I am blown away by an amazing glimpse of a future cinema. The visual experience is at once lifelike and dazzling, visceral and natural, extraordinary and very ordinary.

The dual-projector screening at Origo Studios has been set up by technical supervisor and ASC associate Ben Gervais and his team to deliver what Ang Lee refers to as “the whole shebang”:

• 120 fps playback (of 120 fps footage)

• 3D stereo (using Christie and Dolby’s 6P 3D system)

• 4K presentation (up-rezzed from 3.2K ArriRaw)

• 100 nits to the eye (twice the 48-nit 2D standard)

The “whole shebang” really needs to be seen firsthand for the impact of this technology to be understood. My immediate experience was one of incredible clarity. My brain instantly told me that I was looking at something different from “ordinary” cinema. It felt like looking through a window. It was also apparent that the rendition of movement was different from normal movies. There was no motion blur, judder or strobing whatsoever. The movement of the actors and camera felt much more lifelike.

A common criticism of high frame rate is that “it looks like video.” To me, this felt very natural and comfortable — much more so than 48-fps screenings I’ve seen. One possible explanation is that the absence of strobing, blurring and other motion artifacts is akin to getting rid of “temporal noise,” yielding a cleaner perception of motion and time.

The most important feature of this new format is the amazing presence of the people on the screen. This was especially evident in a lengthy close-up of Will Smith as he delivers an impassioned speech. There was an amazing intimacy and reality to his presence; it felt like he was in the room.

Later, I ask Beebe and Lee about the close-up.

Dion Beebe: The camera is very close. We are within Will’s personal space. The amount of detail we see is incredible. I see the iris of his eye contract, the blood rush into his cheeks, little twitches in his face. As humans, all we do is look at faces. We look for details, we look for answers in faces. We’re not used to looking that deeply into someone’s soul in the cinema. It really is an overwhelming, revelatory moment.

Ang Lee: You can detect Will’s feelings, his thoughts. [There is] nothing we know better than the human face, and nothing is more complex than human nuances. Of course each time you have a new media, it starts out like a gimmick, like a thrill, it’s always spectacles or action, even cheap horror, but then, when it’s easy and cheap enough for artists to pick up, you get something quite genuine and inspiring. It’s the same thing with this media. It’s great for an action movie, with spectacles. But to me the biggest gain is in the close-ups. There’s nothing more spectacular than reading into human faces.

The Budapest Soundstage

When I arrived in Budapest earlier that day, publicist Michael Singer kindly brought me up to speed. After shooting in Glennville, Ga., and Cartagena, Colombia, the production is finishing up at Origo Studios. The vast soundstage sets include several hundred feet of a catacomb tunnel, and a three-story medieval cistern partially filled with water.

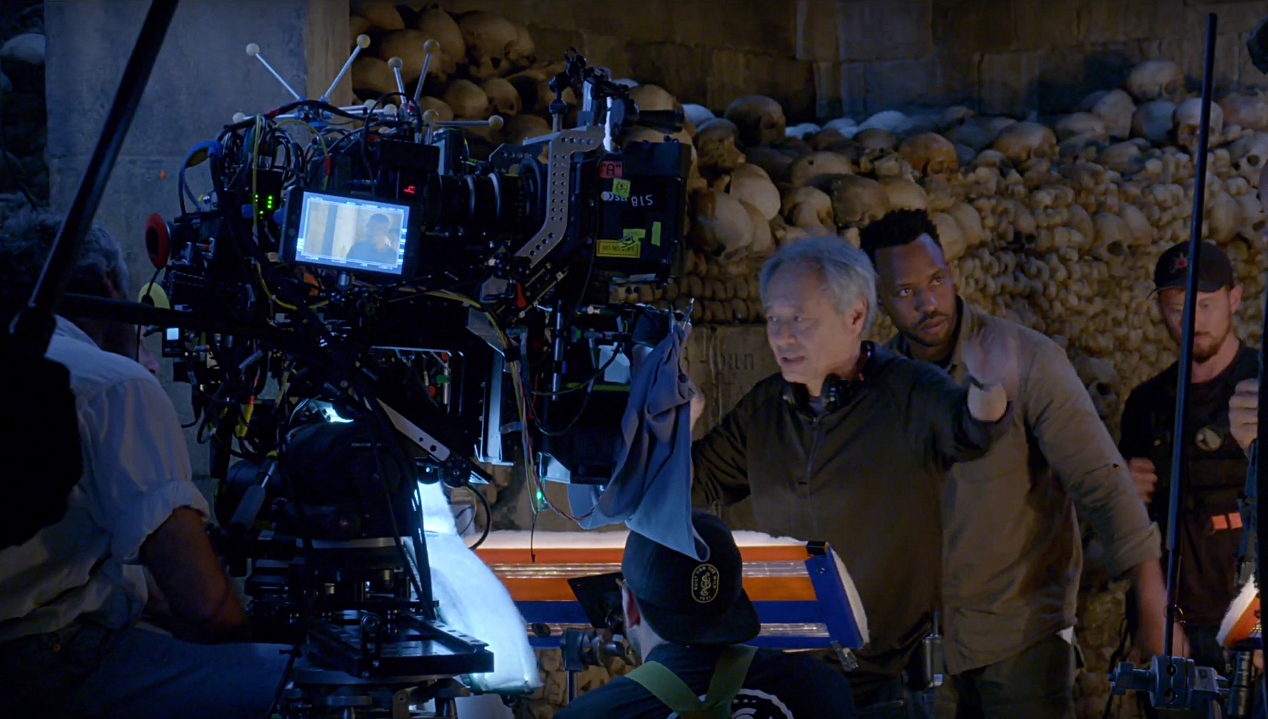

When I walk on set, I am handed a pair of 3D glasses, and I notice that just about everyone watching video monitors on the stage is wearing such specs. The director and cinematographer are about to stage the confrontation between Henry and Junior (played by stand-in Victor Hugo) in the catacombs, a macabre tunnel lined with skulls.

First AC E.J. Misisco is readying an imposing 3D stereo system with two customized Arri Alexa SXT M cameras pointing through the half-silvered mirror of a new, lightweight Stereotec 3D rig. The bulky two-camera system is suspended by the “Donkavator” — a counterweight system invented by key grip Don Reynolds Jr. — so that operator Daniele Massaccesi can shoot a handheld shot with support from above. Don allows me to try the rig, with the camera on my shoulder; I still feel enough weight to be steady, but the suspension system makes it relatively painless to shoot handheld.

I’m struck by the light level on the soundstage. It’s bright. Indeed, 120 fps 3D cinematography requires a lot more light than 24 fps 2D. Gervais explains the exposure math: 120 fps is five times faster than 24 fps, which means that you need five times more light, or about 2 and 1⁄3 stops. He notes that the 120-fps cameras shoot with a 360-degree shutter to capture all the motion. This is a stop faster than the traditional 180-degree shutter, but that gain is more than offset by the 3D mirror, which splits the light between the two cameras and costs at least a stop. Practically speaking, Beebe tells me he needs 21⁄2 to 3 stops more light than he would on a 24 fps shoot.

Ben Gervais explains that the Alexa M cameras — nicknamed Alexa "ALMs", or “Ang Lee Ms” — have been specially modified by Arri to deliver 3.2K at 120 fps, which is then up-rezzed in post to 4K. The modification project was initiated by Arri’s Franz Kraus, an ASC associate member, who asked the filmmakers if Arri could help their next project when he visited the post facility for Billy Lynn. For Gemini Man, Arri ended up modifying nine bodies, enough for three stereo rigs, a spare body on set, a spare at the closest Arri office, and a unit at the factory for design upgrades.

Villages On Set

Gervais leads me on a tour of the technical teams at work on the soundstage, steering me through half a dozen small “villages” with people, screens and gear:

• Lee sits near video-assist operator David Presley, 1st AD Jeff J.J. Authors and producer Jerry Bruckheimer. The director is in a frequent dialogue with stereographer Demetri Portelli to determine a scene’s IA, the InterAxial (aka IO or InterOcular) distance between cameras that determines the amount of baked-in 3D depth; Portelli notes that Lee tends to “choose his lenses wider for the 3D presentation.”

• Beebe works nearby with DIT Maninder “Indy” Saini, grading and matching the 2D images from the cameras for the left and right eye.

• Gervais and his team manage the engineering carts for the pairs of Alexa camera bodies, which are linked to their respective camera heads by fiber-optic cables. A 3D processor orients the images and produces a side-by-side squeezed image for the video assist that is sent to all the monitors on set; the processor is also used to assist the technicians with aligning the two cameras after a lens change and to monitor the signal during shooting. There are also Teradek COLR LUT boxes for each camera. The outputs from this station feed the video assist and DIT.

• Gaffer Jarred Waldron confers with lighting-console programmer Elton James near the desk that controls the intensity of all lights on set via DMX.

• There is also an audio station, and a “producers village” with large 3D monitors.

• There is also an audio station, and a “producers village” with large 3D monitors.

• At the back of the stage there is a large Weta village, which scales up when the production captures a shot of Junior. The team manages up to six Red Raven cameras placed around the set to record action outside the frame, a Lidar system to capture large-scale spatial data, a dozen tiny black-and-white Basler cameras for tracking body motion, and helmet cameras when doing facial tracking of Smith playing Junior. The Weta team is directed by Guy Williams, under the leadership of visual-effects supervisor Bill Westenhofer.

Traveling Lab

Next, Gervais takes me to an adjacent building where he and his team have designed and built a lab to meet this production’s unique needs. The lab travels with the production, processes the footage and creates the “whole shebang” dailies. After principal photography wraps, the lab will move to New York City for editing, color grading, and final mastering for DCPs.

Later, I ask Gervais about the incredible amount of storage in the lab’s air-conditioned machine room.

Ben Gervais: We have a storage cluster from Penguin Computing that runs the BeeGFS high-performance computing storage software. We have 3 petabytes [3,000 terabytes] of hard-disk storage, and 300 terabytes of solid-state storage, all tied together with 100-Gigabit Ethernet. The source media used in the DI [all the assets that made the edit] weighs in at about 360 terabytes, and the archival output of the ‘whole shebang’ version of the film is about 92 terabytes, or 1.8 million frames. By contrast, a 24-fps 2K, 2D film with the same duration would be about 2.3 terabytes, or about 173,000 frames. The DI was done on [FilmLight] Baselight X, with colorist Marcy Robinson and DI supervisor Derek Schweickart.

In a room nearby, I meet editor Tim Squyres, who edits on an Avid while wearing 3D glasses, and he tells me about controlling the 3D convergence during editing to match the background depth of shots in a sequence.

Lighting

Back on set, gaffer Jarred Waldron explains the lighting grid with the help of diagrams by Elton James. The dominant unit is Arri’s SkyPanel S60. There are hundreds of them on the soundstage.

In the catacomb set, dozens of SkyPanels peek through holes and cracks between the skulls on the walls. These are complemented by Waldron’s custom LED strips, which incorporate LiteGear LiteRibbon; the gaffer’s strips are of all shapes and sizes, and are covered by a foam-like diffusion material the crew calls “snow.” The LED strips are plugged into the DMX network via LiteGear adapter boxes, allowing their color and intensity to be easily controlled.

The combination of SkyPanels and LED strips give the catacomb set an overall base ambience. The action in the set involves a rifle flashlight and a flare, which motivate moments of directional lighting that evoke a thriller feel. The flare light is created by a custom source with three 2K bulbs mounted on a metal cylinder. Beebe explains that this source is “wrapped in layers of Full Straw that need constant replacing due to the amount of heat that’s generated.”

The tall cistern set is a three-story atrium overlooking a ground floor full of water. About 60 SkyPanels are placed throughout the intricate architecture to produce a base level of light, along with a big softbox above, fitted with a dozen more SkyPanels.

The action here involves a flare thrown into the water, and its warm undulating light is created by six 1K HydroFlex HydroPars on a custom pipe rig under the water, and also by four motorized Philips Vari-Lite VL3500 Wash units from the upper soft box. The setup is further complemented by a dozen Arri M40s and M90s bounced off the walls. An underwater struggle is shot with a Cameron Pace 3D rig in the water, close to Smith and the double for Junior, who soldier through take after take in the cold water without any breaks.

Dion Beebe

After the production wrapped, I reconnect with Beebe and ask him to explain how he and Lee arrived at their lighting approach for Gemini Man.

Dion Beebe, ASC, ACS: First we looked at Billy Lynn. I think that John Toll deserves a lot of credit for helping to launch this format — it’s such a bold experiment. Ang and I discussed what really worked, what came to life, and what engaged all the gears of 3D and 120 fps. And that was an ongoing conversation throughout production.

American Cinematographer: Even when the image is dark, there is a lot more shadow detail than in most contemporary movies.

Beebe: Yes. We had a lot of nights and dark interiors, and as a rule we really opened up the shadows. We felt that this format is closer to human vision. Humans are designed to look into the shadows to detect danger; we’re always working to see everything we can.

Also, we didn’t want to work wide open. Soft-focus falloff is very much an artifice created in cinema storytelling. It’s beautiful to use shallow focus as a tool, but with 3D, you feel like you’re losing something with shallow focus. You want to see the room. Depth becomes an important part of the audience experience.

So we wanted a constant sense of depth in the image. And we didn’t want solid blacks; we wanted to see details, to give a sense of depth within the frame for the 3D, but also to give our eyes something to fix on when we’re moving through these spaces.

You still manage to get a film-noir feel in the catacomb scene.

Beebe: The goal there was to create this dark, shadowless environment, with the flare and the flashlight adding directional light. Due to the light-loss inherent to this medium, building our base ambient level required a lot of light. Then it becomes a matter of the fill-to-key ratio to avoid shadows falling into solid black, and to maintain depth.

I’m struck by how this advanced technology involves an ‘old-school’ exposure, with a lot of light and lots of fill in the shadows. It’s almost as if you’re shooting slow color stock in the 1950s.

Beebe: That’s true. I had to light for a T11 to get a T4 and 1⁄2 on the lens! We worked with a ‘multiple key’ lighting approach; the lighting wraps around the subject and is multi-directional; intensity is then controlled to shape the image. I am very much of the belief that we seldom find ourselves in environments with only a single source of light. Ang and I debated the idea of 3D lighting throughout shooting, and we have continued to discuss it through post. Just like the first time I shot with a digital camera, on Collateral [AC Aug. ’04], this format presented very unique challenges that required me to rethink my approach to lighting.

A further challenge was lighting the actors when they were inches from our giant 3D matte box. Ang likes the camera to be very close to the actors, with these incredibly tight eye lines. This effectively meant we were lighting from within the matte box. To do this, Jarred Waldron built a bunch of custom LED strips to attach to the matte box, and covered them with his patent-pending ‘snow’ diffusion. Another first for me was when Ang requested we put two eyeball drawings inside the matte box, and he told the actors to look from one eye to the other — which is what we naturally do when looking at someone, without even thinking about it.

Another giant leap was shooting multiple sequences day-for-night. The primary reason was to ensure depth in our night exteriors. I worked closely with VFX supervisor Bill Westenhofer, who created background lights and wonderful night skies. Our rule was that if there were interactive sources in frame that we couldn’t control, like people under streetlights, we would take a traditional night-exterior approach, like the big Glennville shootout — which involved lighting a small town up to a T11 to try and stay above a T4.

The size and weight of the 3D cameras is also ‘old school.’

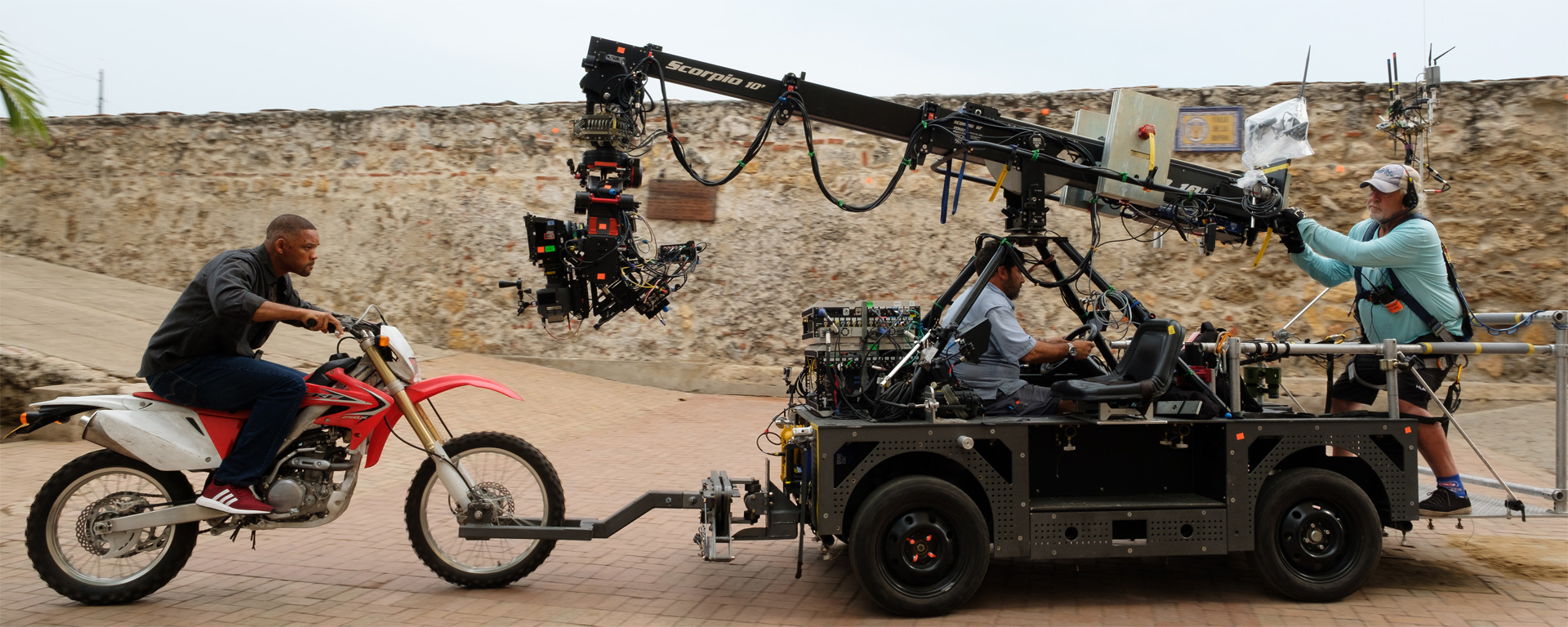

Beebe: We were able to put a 70-pound 3D camera on a motorcycle, a train, a boat and a Steadicam. Ang was dead-set on handheld for the fight sequences, but all the weight sits up front of the stereo rig. So key grip Don Reynolds came up with the ‘Donkavator,’ a counter-balanced system that allowed us to give Ang the high-energy handheld approach he wanted.

What lenses did you use?

Beebe: [Leitz Leica] Summilux and Summicrons. We wanted to create a clean image with depth. In the 3D realm, the biggest challenge is matching the glass on both cameras, in terms of falloff and lack of aberrations. [Leitz] lenses are very precise and hold depth really well.

I was struck in dailies by E.J. Misisco’s very quick focus shifts.

Beebe: In real life we don’t see focus shift when we look at things. Our eyes seamlessly switch between objects, and everything seems to be in-focus. One of the things we therefore tried to eliminate were visible focus pulls.

Pulling Focus and Depth

For more details about shooting in this format, we spoke with first AC Misisco and stereographer Demitri Portelli.

American Cinematographer: Has there been a consistent shooting stop on the movie?

E.J. Misisco: In the catacombs, we had very low light, a T2.8 and 2⁄3. Everything else has been north of T4, around T5.6, and sometimes outside we get to a T8.

What are the most common focal lengths?

Misisco: The 25mm is our master lens; every morning I put that on the finder first. We also shoot with the 21 a lot, and also the 29 or 35. The 40mm is our close-up lens. Occasionally we go to 16 or 18mm, and we do inserts on the 100.

Do you use marks?

Misisco: Occasionally. Will always hits his mark. I never have to worry about him, ever.

When I was watching dailies, I was surprised by your lightning-quick focus shifts.

Misisco: I work really closely with Ang and Dion for this, because a lot of times we edit on the racks. You have to jump the cue and go as fast as you can. When it really works, it’s magic; you don’t see the rack. Shooting at 120 fps changes what you do in every department. Everything is magnified, everything is made more obvious, so the trick is hiding the rack. I’ve been doing this for a long time, and the decisions I made on this movie are very different from other movies.

What are your focus decisions based on?

Misisco: They’re truly based on talking with Ang and Dion, and watching 120-fps 3D dailies every day — that’s the most valuable thing. The first couple of days, Ang would try to describe something, and I wouldn’t quite understand. Then I went to dailies, I saw it, and I said, ‘Oh, now I know.’

For example, if an actor gives you a profile at 3 feet and there’s another actor talking 8 feet away, your eye gets bothered by seeing the strong foreground out of focus. I’ve never been on a movie where focus is so considered. It’s a real consideration.

An artistic consideration?

Misisco: Absolutely. It’s been a real challenge and a joy to think differently about focus.

Demetri, I saw you varying the IA, the distance between the cameras for the left and right eye, during the shot.

Demetri Portelli: The IA increases or decreases the amount of perceived depth. I adjust this during the shot [because] ‘depth management’ is essential for good stereo fusion, as objects get closer or farther away. Ang uses a gear-code shorthand with me: first gear is low depth, fifth gear is a lot of 3D, and we ramp our way up and down his scale, which I like to call the film’s ‘depth score.’ Ang directs the 3D very specifically; he might say to go from gear 2 to 3.5. He is dedicated to the stereo experience and committed along with our team to shoot every shot natively, no matter what the situation. This has been the wonderful challenge for myself and Ben Gervais since Hugo. Ang is indeed a purist of stereo photography.

You also control convergence after the shoot, to determine the screen position and how far image elements will appear behind or in front of the screen.

Portelli: I don’t pull convergence much, because I don’t like [the perception of background depth] to vary between shots. I find it very fatiguing on the eyes. I do sometimes use convergence similarly to focus, mainly in post, to help the audience find the subject in frame faster, especially in fight scenes, but this is not the rule. The [goal for] this HFR [High Frame Rate] technology with stereo is to forget about the screen and to be engaged on a more visceral, ‘real’ level. It is very much about finding truthful stereo images with every setup.

There is an authenticity to what you experience in HFR 3D. It was no small task for Weta and our friends at StereoD to comp into such dynamic native stereo.

Where do you tend to place the actors relative to the screen plane?

Portelli: I will often open up the front for the actor, but I keep the background universe very consistent. For example, I set up some close-ups of Junior right out in the audience, with the screen closer to Henry in the background. Henry’s talking but Junior’s thinking, like an actor standing at the front of the stage. You see his eyes working. The stage is really different than 2D capture. We carefully plan these moments to connect with the audience; we shoot wide and close for roundness, shape and, hopefully, realism.

Distribution

Finally, we had the opportunity to ask Gervais, Beebe, Bruckheimer and Lee about the challenge of distributing a film with this unique format.

Ben Gervais: We prepared versions of Gemini Man in many different format variations: at different frame rates, in 3D and 2D, and with different screen brightnesses. We used RealD’s TrueMotion software, with developer Tony Davis, to fashion synthetic shutters that skillfully transform the 120 fps into 60- and 24-fps versions. Most theaters should be able to show the 60-fps 2K 3D version.

I especially encourage cinematographers and filmmakers to try to see the ‘whole shebang’ in China, where it will be shown in about 100 theaters at 120-fps 3D 4K, using new dual-projector systems built by Christie. In the U.S. and Europe, I encourage professionals to see the 120-fps 3D 2K version that will be shown in select Dolby Vision theaters.

Dion Beebe: I hope that as many filmmakers as possible get the opportunity to see the ‘whole shebang.’ I don’t have any doubt that high frame rate will be a key element in creating future big-screen event experiences.

This is a new medium that has the potential to offer a different sort of truth. Emotionally, 24 fps feels like the cinema of dreams, and 120 fps the cinema of reality. We haven’t really pushed the boundaries of what digital cinema will allow us to explore. This is just the beginning.

Jerry Bruckheimer: We have got to change the theater experience because there’s so much great television. If the audience are going to pay money to go to the theaters, you better give them something really special. And the technology has to be part of it. Kids are used to looking at 120fps in video games. We’re taking the next step.

The audience is there. You have to deliver, not what they think they want, because they don’t know what they really want until they see it. If you ask them, chances are they can’t quite articulate it. But once they see this, they will say: “We’re there, this is really fascinating”.

Ang Lee: What I hope is that people will recognize, even in the first attempts, that this has great artistic potential.

Benjamin B: How does it feel to be the pioneer of this new medium?

Lee: Like the marine landing on the beach, facing the machine gun, lying on the barbed wire — the marine that people step over! [Laughter.]

I don’t mind doing that, though I would also like to plant the flag.

Many thanks to Ben Gervais for additional documentation and Elton James and Jarred Waldron for the lighting plots.

TECH SPECS

1.85:1

120-fps 4K 3D Digital Capture (up-rezzed from 3.2K)

Customized Arri Alexa SXT M,

Vision Research Phantom Flex4K (for slow-motion effects), Red Helium (for aerials),

Sierra Olympic thermal-imaging cameras

Leitz Leica Summicron-C, Summilux-C

Stereotec 3D rigs,

Cameron Pace underwater 3D rigs

Digital grade with FilmLight Baselight X