Hell on Wheels: Collateral

For director Michael Mann’s crime taut thriller, cinematographers Paul Cameron and Dion Beebe, ACS exploited the low-light capabilities of HD cameras to depict a nocturnal urban world.

Unit photography by Frank Connor

Photos courtesy of DreamWorks Pictures

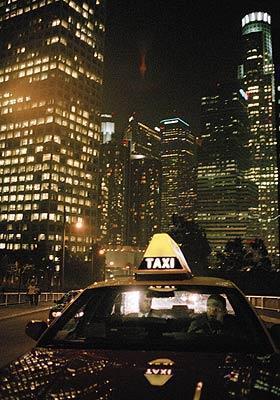

In Collateral, a lonely taxi driver, Max (Jamie Foxx), agrees to chauffeur the smooth-talking Vincent (Tom Cruise) around Los Angeles for an entire evening. He soon discovers that Vincent is running an unusual errand indeed: he is a mercenary who is methodically eliminating five witnesses scheduled to testify against a drug cartel in federal court. Unable to escape Vincent’s grasp, Max quickly becomes the chief suspect in the murders, and as federal and local law-enforcement officials close in on the duo, Max realizes his only way out is to prevent Vincent’s final murder.

Collateral director Michael Mann had experimented with high-definition (HD) video for a few scenes in Ali (AC Nov. ’01), and he went on to produce the television drama Robbery Homicide Division, which was shot entirely with Sony/Panavision 24p CineAlta HDW-F900 cameras (AC Feb. ’03). Intrigued by the format’s potential for feature filmmaking, Mann decided to use it on the extensive night-exterior work in Collateral to make the most of available light in and around Los Angeles. “Using HD was something Michael had already settled on by the time I came aboard,” recalls director of photography Paul Cameron (Man on Fire, Gone in 60 Seconds [AC June 2000]), who prepped Collateral and shot the first three weeks of principal photography. “He wanted to use the format to create a kind of glowing urban environment; the goal was to make the L.A. night as much of a character in the story as Vincent and Max were.”

“In film, photochemical magic takes place in the falloff and in the highlights, but HD reacts very differently — once you start pushing the gain, you have to carefully monitor your signal-to-noise ratio.”

— Paul Cameron

Cameron spent several weeks testing the available 24p HD packages — the Thomson Grass Valley Viper FilmStream, the Sony/Panavision F900, and the Sony F950 — and comparing the 35mm film-outs to footage shot on four high-speed Kodak stocks: Vision 500T 5279, Vision2 500T 5218, Vision2 Expression 500T 5229 and Vision 800T 5289. (He pushed all of the stocks by two stops, rating the 500-speed emulsions at ISO 1600 and the 800-speed emulsion at ISO 2500.) “It became pretty apparent early on that the only way to get the look Michael wanted was to shoot HD and push the gain on the cameras,” says Cameron.

“We ruled out the Sony F950 early on, mostly because of the optics,” continues the cinematographer. “I felt the image was a bit too soft, even with Zeiss DigiPrime lenses. Another drawback to the F950 was that you had to have a separate recorder, which meant we would always be tethered to that deck with an umbilical cord. Although many improvements were made to that system on Star Wars: Episode III, I didn’t feel it was production-ready. The F900, on the other hand, is a tried-and-true workhorse, and it yielded absolutely sharp results with the DigiPrimes.”

The Thomson Viper has been lauded for its 4:4:4 uncompressed raw-data FilmStream mode, in which the pure image signal is sent to a hard drive, but Cameron found that this mode of shooting posed several practical problems. Because the signal undergoes no processing and is viewed on a monitor in “raw” form, the resultant images have a sickly, greenish hue. “That yellow-green image didn’t represent anything we could see by eye,” says Cameron, “and that made it impossible to judge the image from the monitor. If we passed the signal through an RGB processor and looked at a composite image, we were looking at a very compromised picture that didn’t reflect the image quality of the FilmStream mode at all. Also, when we increased the gain in the FilmStream mode, we weren’t seeing any results. In order to get the look Michael wanted, we had to push the camera beyond its normal mode.”

Cameron discovered that although shooting in VideoStream mode resulted in a slightly compressed image, the ability to modify the image via the camera’s internal matrix menus was a much better choice for the look that Mann wanted, and resulted in a superior picture for the film-out tests. Still, there were additional problems. “The Viper was just not production-ready,” says Cameron. “First off, we had to manufacture several accessories for the camera — a mattebox, new lens rods and base plates.” And because the Viper is not equipped with any recording device [internal deck or hard drive], “we had to make a fiber-optic umbilical to attach the Viper to the recording decks, and it’s difficult to work with any kind of tether.

“You can record into an HD deck or you can record to a hard drive,” explains Cameron. “We looked at the Director’s Friend/DVS CineControl [see New Products, AC Dec. ’03], but that device is far too large and cumbersome to lug around in real-world shooting. Bryan Carroll, Michael Mann’s technical adviser, came up with the S-2, a hard drive that’s about as big as a 1000-foot-magazine case. The system wasn’t specifically designed for the Viper, but it was applicable. However, it was difficult to retrieve the material from the hard drive, and that sent up a red flag with the studio; they demanded that we have a backup system if we decided to shoot with the Viper, so suddenly we were looking at the S-2 drives and an HD recorder. The gear attached to the camera was doubling.”

The S-2 drives had a recording capacity of about 40 minutes, but in the end, the filmmakers decided not to use the redundant hard drives. Instead, they opted to simply record the Viper VideoStream signal to the new Sony SRW5000 HD deck, a proprietary system manufactured for the Sony F950. The production had four prototype SRW5000 decks, two in the field with the Vipers and two at Laser Pacific (acquired by Technicolor in 2011), where the HD footage was transferred to 35mm.

The production began shooting with a pair of Vipers, but Cameron testifies that “by the end of the first day, we switched to two F900s as our main cameras.”

To achieve the light sensitivity Mann was after, Cameron found that he had to push the cameras’ image gain in order to achieve exposure in the available ambient light. He found an acceptable signal-to-noise trade off within the range of +3dB to +6dB on the F900. “There is a very thin line with the threshold of noise in all of the HD systems,” he explains. “In testing the F900, we found that some things looked great on the monitor at +3dB or +6dB, but when we made the film-out, those scenes picked up even more noise when projected on film on the big screen.

“Basically, HD shooting has to do with signal-to-noise ratio,” continues Cameron. “In film, photochemical magic takes place in the falloff and in the highlights, but HD reacts very differently — once you start pushing the gain, you have to carefully monitor your signal-to-noise ratio. Our biggest concern was how to deal with the noise in scenes that show Tom and Jamie in the cab, and those scenes comprise about one-third of the movie. We discovered we had to increase the signal — meaning the amount of light — on the actors’ faces to an acceptable IRE level [registered on a waveform monitor], knowing that we’d later bring it down digitally with Power Windows in color correction before the film-out. What looked great to the eye didn’t necessarily translate into a good-looking close-up on the final film-out.

“We therefore found ourselves running a fine line,” he continues. “We’d light beautiful night exteriors that looked amazing and natural and had so much detail, but when we went in for the close-ups, we had to overlight the actors to reduce the noise on their faces. On the monitor, it looked horrible and incredibly overlit. It was very hard to wrap my head around what we were doing, and it went against every instinct I have as a cinematographer. It was a constant battle between what looked good on set and what would look good at the film-out every weekend.”

The filmmakers discovered that any levels below 20 IRE at +3dB or 30 IRE at +6dB on the actors’ faces rendered an unacceptable amount of noise on the projected film image. Respectively, 20 and 30 IRE are roughly equivalent to 21⁄3 stops and 11⁄2 stops below medium gray (about 55 IRE) on a video signal. According to Cameron, at those gain levels in VideoStream mode, the Viper was actually more sensitive to low ambient light, with less noise, than the CineAlta.

Mann was also insistent about the kind of lighting he wanted for the taxi interior, which Cameron describes as “no light, really. Michael wanted it to feel like ambient light with no specific source. That, coupled with the challenge of filming in a real cab that had little or no room to place any kind of lights, made it incredibly challenging to design an effective plan.”

After investigating many options, Cameron and his chief lighting technician, Phil Walker, chose a new fixture: Electrolumi-nescent Display (ELD) panels. The thin, flexible pieces of plastic encase laminated phosphors and operate much in the same way that Indiglo watches and mobile-telephone displays do. Walker worked with NovaTek, a manufacturer of ELD panels, to custom-create a mixture of phosphors that would provide an acceptable color temperature for the HD cameras. “In the beginning, Michael preferred a warmer color temp, but we eventually settled on a slightly cool green that looked very natural,” recalls Cameron. “That was the easy part. It then took about four weeks to get the panels made, which left us with about a week before principal photography to set them up in the cabs.”

Adding another dimension to the tight timeline was that the production called for four fully functional taxis and three custom-built trailers with various sections of the cab (one for shooting from the front without a windshield, one for shooting through the passenger side, and one for shooting through the driver’s side), which meant there were seven “sets” that had to be rigged with ELD panels.

“The custom trailers were very interesting — we called them ‘Popemobiles,’” says Cameron. “They were basically sliced sections of the cab that were walled in with large panes of Plexiglas that eliminated wind noise yet still let in available light while we were moving. They were constructed on extremely lightweight trailers that got the cars as low to the ground as possible and still had great suspension. The rig gave us a mobile soundstage, which was wonderful.”

Inside the cab, Cameron and Walker wired more than 30 leads in various positions for the ELD panels. Each panel was about 8" x 15" and could be placed anywhere and hooked into a lead in just a few seconds. The leads traced back to a custom-built dimmer board, and each panel could be dimmed to nearly 20 percent without any change in color temperature; the device could also run off either a generator or batteries. “You can cut the panels into any shape, but we made most of them in uniform sizes and just cut a few to slip into tight spaces,” says Cameron. “No matter what the size, all of the panels could run from the same lead, so we could switch a 4-by-4-inch panel out for an 8-by-15 and keep the same lead. In the end, we wound up with about 30 ELD panels in each cab.”

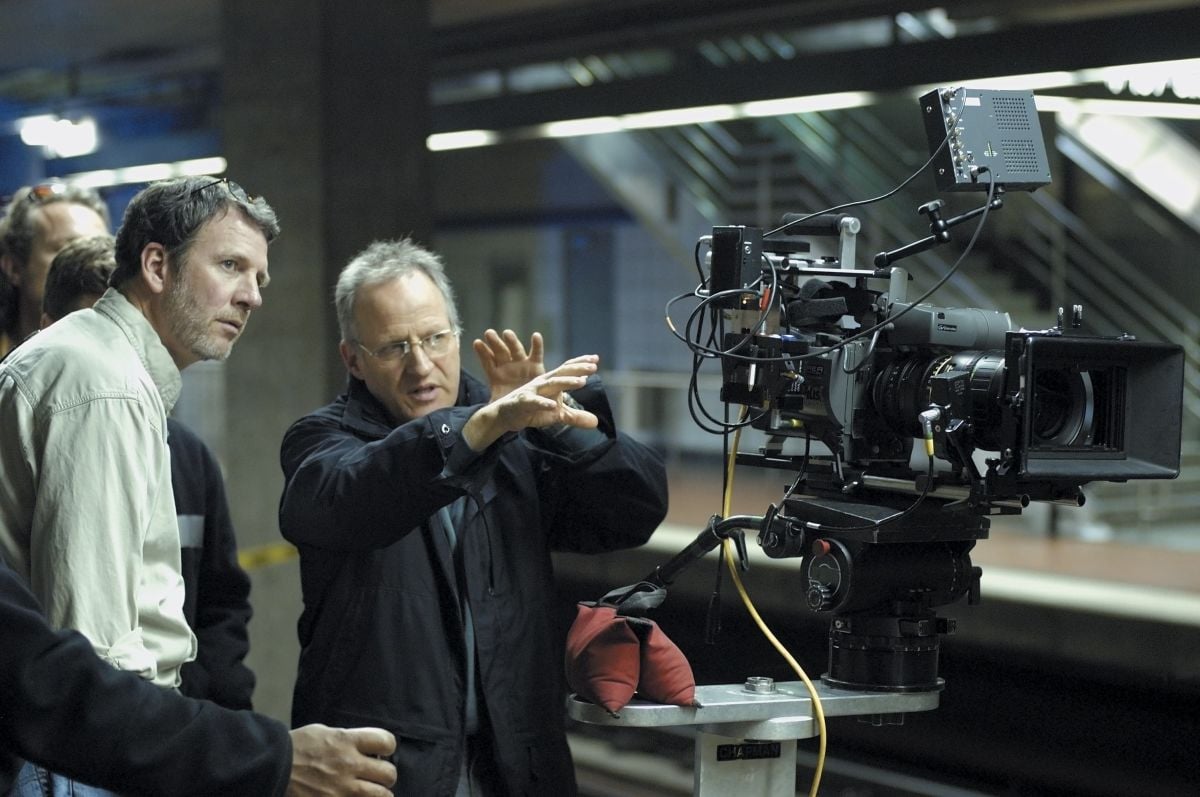

About three weeks into the 12-week shooting schedule, creative differences led Mann to replace Cameron with Dion Beebe, ACS (In the Cut, Chicago). Shortly thereafter, Walker voluntarily left the project and was replaced by his best boy, Felix Rivera. “It was one of those situations where we met on a Friday, prepped over the weekend and then started on set on Monday,” recalls Beebe. “Replacing another cameraman was something I’d never done before and would not normally consider doing. Every cinematographer has his or her own identity, sense of working and lighting style, and no one wants to step into a situation where he’s merely there to replicate someone else’s work. When I first spoke to Michael, I was very clear that I didn’t want to come into a situation like that. We met and reviewed a lot of the footage that had already been shot, and Michael said he wanted me to bring my own style to the film. Of course, Michael has a very strong visual sense, and on a Michael Mann film, you’re working very closely with him to realize that.

“Under the lighting plan Paul and Phil developed for the taxi interiors, the ceiling, doors and back panel were covered in a fabric that we could affix the ELD panels to with Velcro, thereby surrounding the actors with light,” continues Beebe. “We had the most difficulty with Jamie because he was wearing glasses, and with the cameras always moving, we were constantly fighting the reflections of the light panels, even when we used non-reflective glasses on him. We ended up adding some Mini Flo fixtures in the cab to get some throw and work around his glasses, because the ELDs fell off pretty quickly.”

Beebe continued overlighting the actors’ faces to 20 or 30 IRE, even though the background information barely registered on the waveform monitor. “Almost everything was off the scale of my meter,” recalls the cinematographer, who uses a Pentax digital spot meter.

By the time Beebe joined Collateral, the Viper accessories were ready, and the production switched from dual F900s to dual Vipers as the A and B cameras. However, whenever the camerawork was run-and-gun, they used the F900s to avoid the Viper’s tether system.

“Michael [Mann] is an incredibly demanding director. He’s very demanding of everyone, especially his camera crew, but it’s inspiring to work with him because he has such a clear vision of what he wants, and he’ll pursue that without compromise.”

— Dion Beebe, ACS

One benefit of the Viper system is the ability to do a native internal anamorphic squeeze. To achieve the 2.40:1 aspect ratio on the F900, the image has to be cropped from 1920x1080 to approximately 1920x764, which is later optically squeezed for the laser-out (much in the same way an anamorphic print is struck from a Super 35mm 2.35:1 negative). The Viper features an anamorphic setting that fills the full 1920x1080 pixel image area with a 2.37:1 squeezed image. “In terms of their sensitivity, the F900 and Viper are well matched,” notes Beebe. “They render colors slightly differently and have differences in how they handle highlights, but primarily it was the anamorphic squeeze that affected the film-out. The F900 had to be cropped, whereas the Viper used the camera’s full resolution; therefore, in this format, the Viper results were superior.”

The internal anamorphic squeeze created some difficulties for the camera operators, however. Although the camera can send an unsqueezed image to the viewfinder, there is a slight delay because of the image processing, and the time lapse proved to be unacceptable in most situations. In order to avoid the delay, the operators typically chose to work with a squeezed image in the viewfinder. “We also got a delay on the monitors when we went unsqueezed,” adds Beebe. “And because of that delay, the sound was always out of sync. I’m sure that Thomson has fixed a lot of these problems by now, but the cameras were literally being modified and rushed to the set while we were shooting, so we had to learn to deal with it. Michael loved the results we were getting, so we modified what we could and lived with what we couldn’t.”

One of the modifications the Vipers underwent during the shoot was the addition of covers for the controls on the camera, so that the buttons and switches could not be accidentally hit during shooting. “Because we were always shooting at night, we were like vampires, dreading the rising sun and scrambling to make the night before the break of day,” recalls Beebe. “One night, I was inside prepping a scene and Michael was outside shooting another. I ran outside and looked at the monitors and found one of the cameras to be horribly diffused. It looked like the back element of the lens had fogged over or been smudged, but because everyone was rushing, no one had noticed the change. Between takes, we quickly switched out the lens, checked the calibration and ran through a checklist of possible causes. In the end, it turned out someone had bumped the camera’s internal filter wheel and dialed in a diffusion filter. Those types of idiosyncrasies are totally new for a camera team that’s more familiar with film cameras.”

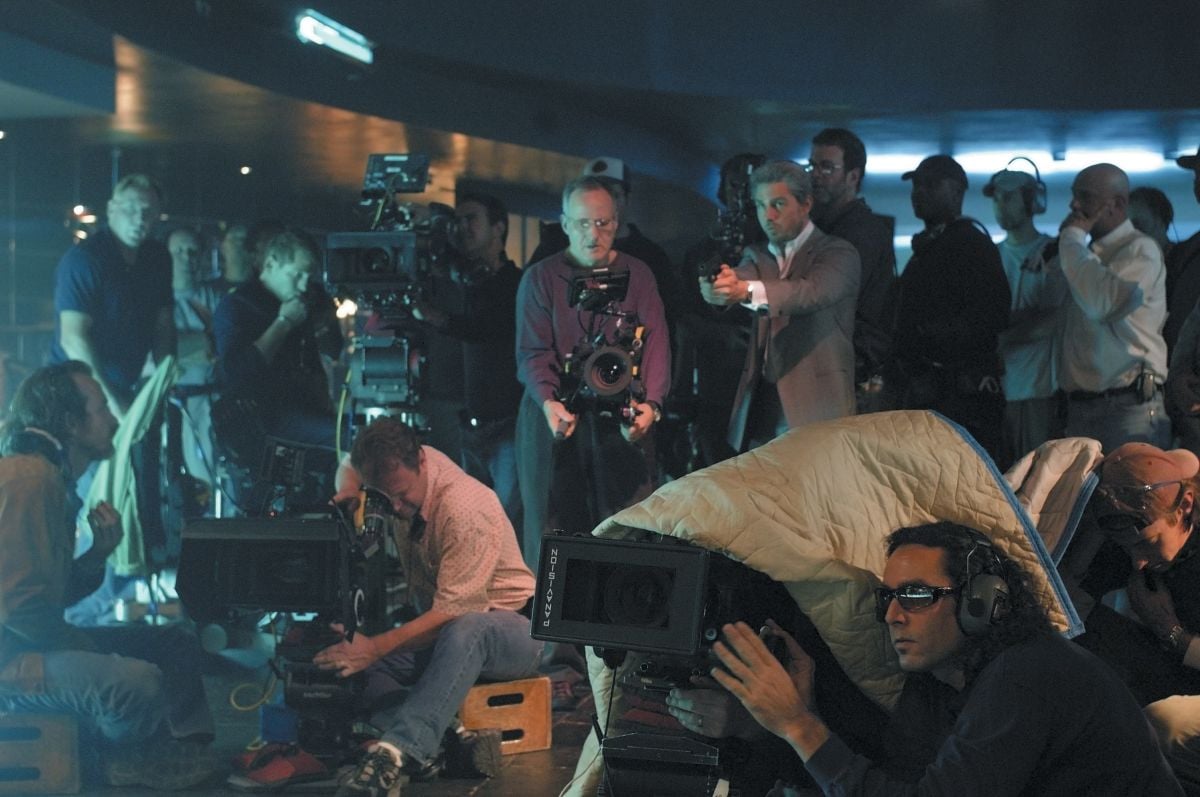

At the filmmakers’ request, Thomson also added weight to the back of the Viper to make it more balanced for handheld operation; the camera was initially very difficult to handhold without the added ballast of a magazine hanging off the back of the camera. “Our A-camera operator, Gary Jay (above), an amazing operator who has worked with Michael for many years, and our B-camera operator, Chris Haarhoff (above), were really able to work these cameras to their advantage,” says Beebe. “An odd byproduct of the HD world, especially with so much handheld operation, was that our focus pullers, John Grillo and Glen Brown, ended up working primarily via remote focus, sitting at the monitor. The HD monitors are so crisp and sharp that the best way to judge critical focus is simply to watch the monitor.

“One of the amazing things about hi-def is that to a degree, you’re seeing your final image on the monitor,” he continues. “There is also a lot of flexibility to alter that image on the set, and it’s important to make decisions about saturation and contrast early on because there’s an infinite amount of tweaking you can do. It’s easy to find yourself being seduced into tweaking colors and losing sight of the movie’s overall visual continuity. There was a real discipline to stick to the settings that Paul and Michael had settled on during prep. The only real adjustment we made was to selectively reduce saturation on a number of exteriors. L.A. has a lot of mixed color at night — sodium vapors, mercury vapors, tungsten light, neon and fluorescents — and when mixed together within a frame, they often created an image that Michael thought looked too ‘fruity’ and detracted from the mood of the scene. Adjusting these colors involved sitting with Michael and Dave Canning, our digital-imaging technician, at the monitors and setting the color levels we liked, being careful to stay within range of our pre-set levels of desaturation.”

Overall, Beebe was impressed with HD’s capabilities: “The format’s strong point is its incredible sensitivity to light. We were able to shoot Los Angeles at night and actually see silhouettes of palm trees against the night sky, which was very exciting.”

With regard to signal-to-noise ratio, Beebe discovered that the HD cameras could be pushed even further than +6dB in certain situations. “+12dB is really the threshold of where you’d ever want to go,” he remarks. “We ended up doing +12dB only on the F900. We pushed the Viper to +9dB, but that was the highest we ever went. The real key was to keep the actors’ faces in an acceptable range. As a viewer, your focus is always on the actor, and we found we could get away with a lot of noise in the background as long as we weren’t seeing noise on the actors’ faces.”

Throughout the shoot, Beebe and Mann viewed dailies via HD projection set up at Mann’s Forward Pass offices. The projector was carefully calibrated to emulate the look of the 35mm laser-out that was being done by Laser Pacific.

On night exteriors, Beebe often lit as little as possible. “Michael coined a phrase early on: ‘Make the fill light the key light,’” recalls the cinematographer. “We wanted to avoid a sense of directional lighting. Also, we were cross-shooting a lot with two or more cameras and incorporating a lot of camera movement into shots, so we always had to allow for that within our lighting setups. That meant making use of a lot of practical lighting and keeping our film lights off the floor.”

Beebe tried working with helium lighting balloons, but abandoned them because they lit up the street surface beneath them too much. He and Rivera then found that Kino Flo Image80s did the job; the fixtures were wrapped in ND.6 with two or three layers of muslin, in addition to the color pack for mercury-vapor (1⁄4 CTS and 1⁄2 Plus Green on daylight-balanced tubes) or sodium-vapor (Light Amber and 1⁄2 Plus Green on tungsten tubes) fixtures. “We turned the Image80s into very low-level soft sources that could supplement the available light, match the color temp and create a non-directional source,” says Beebe. “Sometimes we added 1⁄4 or 1⁄8 CTB to the sodium-vapor gel pack if it was reading too warm. That’s another advantage to HD — you can fine-tune your color pack because you can see immediate results on the monitor. If there’s a shift in the color temperature, you can instantly make the correction and match it completely.”

The picture’s final sequence, set on the 14th floor of an office building in almost no light, pushed the HD cameras to their limits. “The offices were entirely made of glass — it was basically a hall of mirrors,” recalls Beebe. “We were seeing the cityscape reflected in each pane of glass and often playing the actors as silhouettes against the reflections. For that sequence, we used the Viper and F900 alternately and sometimes pushed them both to the max [+9dB and +12dB, respectively]. It was remarkable! We were literally shooting in levels you could barely see with the naked eye. It was a bold use of the cameras, and I break into cold sweat just thinking about it. Any time we tried to bring in a light, we’d see it reflected multiple times over in all that glass.”

To add some light on the actors, Beebe and Rivera created Kino Flo wands. Key grip Scott Robinson cut some black PVC tubing into which 4' and 2' Kino Flo tubes were placed and then covered in layers of bobbinet. The wands were laid on the floor or rigged into the ceiling to avoid creating reflections, and Rivera occasionally handheld a wand or two and walked next to the camera or hid behind a desk to help bring up the actors’ faces.

Collateral’s big interior scenes, which comprise about 20 percent of the picture, were shot on 35mm, according to Beebe. “It was decided early on that night-exterior scenes would be shot on HD and controlled interior scenes would be shot on film,” he says. “That made sense, as we were not relying upon available light levels to set our parameters. We did, however, need to create a look on film that worked seamlessly with the look of HD. I decided to switch from the Vision [500T] 5279 that had been used before I started to [Vision2 500T] 5218, which I found integrated with the HD footage a little more easily.

“Shooting film also allowed us to shoot at variable frame rates and expand our camera package to include things such as the Frazier lenses and modified Eyemos,” he continues. One such scene, set in a nightclub, is a shootout involving Vincent, the L.A.P.D. and members of the drug cartel that has hired Vincent to commit the murders. Beebe shot the sequence on 5218, which he pushed one and sometimes two stops.

“There’s another sequence in a Korean bar that was all lit with black lights,” says the cinematographer. “We tested HD and film cameras in that environment and found that although the HD cameras were more sensitive than the film, the overall image was far too saturated under the black lights. It was too crisp and colorful and the feeling was distracting, so we went with 5218.”

Additionally, the production used film cameras on all day-exterior scenes and on stunt sequences that called for slow motion and additional coverage. “For one stunt sequence, we were running 12 cameras simultaneously: eight film cameras, two Vipers and two F900s,” recalls Beebe. “Trying to maintain consistency in terms of look and exposure was an absolute nightmare. We had HD cameras with incredible sensitivity running alongside film cameras that were shooting at high speeds — one of the film cameras had an 11:1, which only opens to T2.8, and Michael wanted it running at 48 fps. This, alongside a Viper working at +6dB gain with a DigiPrime at T1.3, created a huge gap.

“The only way to close the gap was to push the film — up to three stops on some of the cameras. I was very careful about which camera was being pushed; it was often the crash cams or something I knew wouldn’t be used for very long. I tried to avoid pushing any camera too much if I thought the shot might last longer than five or 10 seconds onscreen. You want to make sure you capture the information and action, but because it is action, you can bury some things into the pace of the scene. I was very happy with how well 5218 held up in those tough conditions and how well it all matched up with the HD.

“Michael is an incredibly demanding director,” Beebe says in conclusion. “He’s very demanding of everyone, especially his camera crew, but it’s inspiring to work with him because he has such a clear vision of what he wants, and he’ll pursue that without compromise.” He adds with a chuckle, “Before I started working with him, he was described to me as ‘a director who prepares like Rembrandt and executes like Picasso,’ and I felt that was pretty insightful.”

TECHNICAL SPECS

2.37:1

High-Definition Video and 35mm

Sony/Panavision 24p HDW-F900; Thomson Viper

Zeiss DigiPrime lenses

Panaflex Millennium, Millennium XL, Pan/Arri 435

Primo lenses

Kodak Vision 500T 5279, Vision2 500T 5218

Digital Intermediate by Company 3 HD transferred to 35mm by Laser Pacific

Printed on Kodak Vision Premier 2393

Editor’s Note: Both Cameron and Beebe later became members of the ASC.

For further reading on the early use of HD cameras in feature production, you’ll find our extensive coverage on director David Fincher’s work with Harris Savides, ASC on the 2007 thriller Zodiac here.