Guillermo del Toro: Fantastical Visions

The ASC salutes a singular visual artist with the Board of Governors Award.

This article will appear in American Cinematographer's March 2026 issue. For full access to our archive, which includes more than 105 years of essential motion-picture production coverage, become a subscriber today.

2025 was a banner year for Guillermo del Toro. In addition to completing a passion project with Netflix’s lavish production of Frankenstein, shot by Dan Laustsen, ASC, DFF (AC Dec. ’25), the Guadalajara-born filmmaker received a Special Recognition honor for Cinematographic Merit at the Ariel Awards, Mexico’s equivalent of the Academy Awards — and this year, on March 8, he will be honored with the ASC Board of Governors Award.

“This Mysterious Position”

Del Toro — whose films often betray an affinity for tender-hearted monsters contending with real-world horrors — describes his fascination with the macabre as “an almost religious calling” that he slyly attributes to a strange fusion of Catholic dogma and “cosmology with monsters.” The passion was kindled with his first cinema experience in 1960s Guadalajara, when his mother took him to see a Spanish-language presentation of William Wyler’s Wuthering Heights, an Oscar winner for Gregg Toland, ASC. It was retitled in Spanish as Cumbres Borrascosas (Stormy Heights).

Also Read: ASC to Honor Guillermo del Toro with Board of Governors Award

“That made a big impression,” he recalls. “It scared me. I was also born just in time for the apex of sci-fi television: The Outer Limits, The Twilight Zone, The Alfred Hitchcock Hour. I was drawn towards the gothic side of visuals.” This diet of eerie fantasy inspired del Toro to embark on his first experiments in Super 8 filmmaking in 1972 at age 8. “I was already a big fan of Famous Monsters magazine and the films of Ray Harryhausen, so I tried to make a little animated movie — bad stop-motion — using my Planet of the Apes figures. My father had gotten a Super 8 camera as a partial payment for a car he sold. It came with a projector and a foldable screen.

“I understood few of the [crew] positions on film,” he continues. “I knew there were stuntmen, animators and makeup-effects guys. I was dreaming of all of that, but then, when I was 10 or 11, I found there was this mysterious position: the director. I collected Super 8 one-reelers of Vincent Price movies and Universal classics; I had The Curse of the Crimson Altar, The Raven and The Tomb of Ligeia. I bought a little editing machine and started to understand how cuts would work. By 11 or 12, I felt that was my calling — to direct.”

“Eye Protein”

In his teens, del Toro acquired a more sophisticated Super 8 camera, the Canon 1014XL-S, with 1-36 fps, 150- and 220-degree shutter settings and a 6.5-65mm zoom. He submitted his “dailies” footage of his homemade horror films to a local pharmacy, which dispatched reels to the Kodak processing plant in Mexico City and returned the results in about a week. High-school screenings introduced del Toro to a group of local film critics, and that led him to the film-studies program at the School of Audiovisual Arts at the University of Guadalajara. “I became one of their youngest film critics,” he says. “We were the first generation of students there.”

Filmmaker Jaime Humberto Hermosillo, a co-founder of the Guadalajara International Film Festival with del Toro, was a nurturing influence. “Jaime was a mentor to my whole generation in Guadalajara,” del Toro says. “He taught three years of screenplay writing. He allowed everybody to work on his movies. He was an indie director, and I got to produce one of his movies when I was 19. All I wanted to do was Mexican film.”

Del Toro’s approach was informed by his hands-on artistic talents. “I loved storyboards, set design, set building, sculpting and makeup effects. I was already doing that for all my Super 8 films, and I felt strongly that it would give me the possibility of making my movies look bigger, and to control the narrative that those elements brought to a story.” He subscribed to a three-year correspondence course run by legendary makeup-effects artist Dick Smith. “Learning that, [along] with stop-motion and optical effects, allowed me — and still allows me — to deliver movies with what I call ‘eye protein’ instead of eye candy. Telling the story through audiovisual means allows my movies to look far more expensive than they really are.”

“Now I’m Listening”

Limited technical resources in Guadalajara required del Toro to embark on his own R&D, tracking down Stateside suppliers of sculpting, molding and latex materials and locating their Mexican equivalents. “There were no makeup-effects supply companies [in Mexico] because there were no makeup effects!” After abandoning a first attempt at a stop-motion feature, he turned to live action.

He connected with Guillermo Navarro, ASC, AMC while storyboarding an action sequence for Alejandro Pelayo’s Morir en el golfo, which Navarro was shooting. “I was explaining to Navarro what lens the storyboards represented and what the distance needed to be with the camera. He said, ‘Stand in front of the camera and show me what I’m seeing.’ So, I stood and pointed, ‘This is the edge on the bottom [of frame], and this is the edge on the top.” He smiled and said, ‘Okay, now I’m listening.’”

Del Toro created makeup effects for Navarro’s next production, the period adventure Cabeza de Vaca, which the cinematographer’s sister Bertha produced, and a friendship blossomed. “Bertha became my producer on many of my movies,” del Toro says. “She asked me, ‘Do you have a screenplay?’ Back then, I had a script called Aurora Gray’s Vampire. That became Cronos.”

“The Closest Relationship”

Production of Cronos required an almost crippling investment of $250,000. “I remember trying to pay that,” del Toro recalls. “But then the movie won the main award in Critics Week at Cannes, and it had incredible showings at MoMA and Sundance.” Universal Studios production executive Nina Jacobson offered to commission more of del Toro’s screenplays, which led him to Hollywood. “I would have continued to make Mexican films all my life, but Mexican [production companies] were not interested,” he says. “They told me they were only interested in non-genre independent film. I kept saying, ‘I believe there’s art, beauty and power in storytelling in genre movies.’”

Del Toro’s relationship with Navarro deepened as their work evolved. “The closest relationship on a film set is director and cinematographer — they are the two thrones at the end of the hallway,” del Toro opines. “You have to have somebody that you trust entirely with the light, and they trust you with the lens, the composition or the camera move; only then can you have a dialogue in which you are equal partners. You learn to operate with half of your brain hemisphere becoming the cinematographer’s brain. You have to trust them.

“Back then,” he adds, “there was no video tap, so the cinematographer relied on looking through the camera viewfinder, and the director mostly stood by the side of the camera.”

Dan Laustsen, ASC, DFF shot the 1997 feature Mimic, del Toro’s Hollywood debut, and Gabriel Beristain, ASC, BSC, AMC joined the director for Blade II, but Navarro continued to accompany del Toro on Mexican productions, which were intertwined with deep veins of Hollywood pop culture. “We learned a lot about the equipment on the bigger movies, and we gained a lot of freedom when we did the smaller movies,” the director recalls. “The equation was simple: more money, less freedom. When you achieve a certain notoriety, you can balance a higher budget, but for the first part of our [creative] life, we had to choose one or the other.”

Political undercurrents emerged as recurring themes, especially in the nightmarish fascist regimes that haunt The Devil’s Backbone (AC Dec. ’01) and Pan’s Labyrinth. “The political dimension of fantasy was never lost on me,” del Toro says. “The horror tale’s provenance is fairytale and parable, and parable is a great way to address philosophical or political matters — that’s why oftentimes the parable and the fable intersect. That was clear to me at a very young age. In Cronos, we attempted Catholic superimpositions onto the vampiric myth. If you manifest fantasy in a political environment, they illuminate each other in a way that is absolutely unique. The political parable becomes more poignant, and the fantastic element seems more rooted.”

The Digital Palette

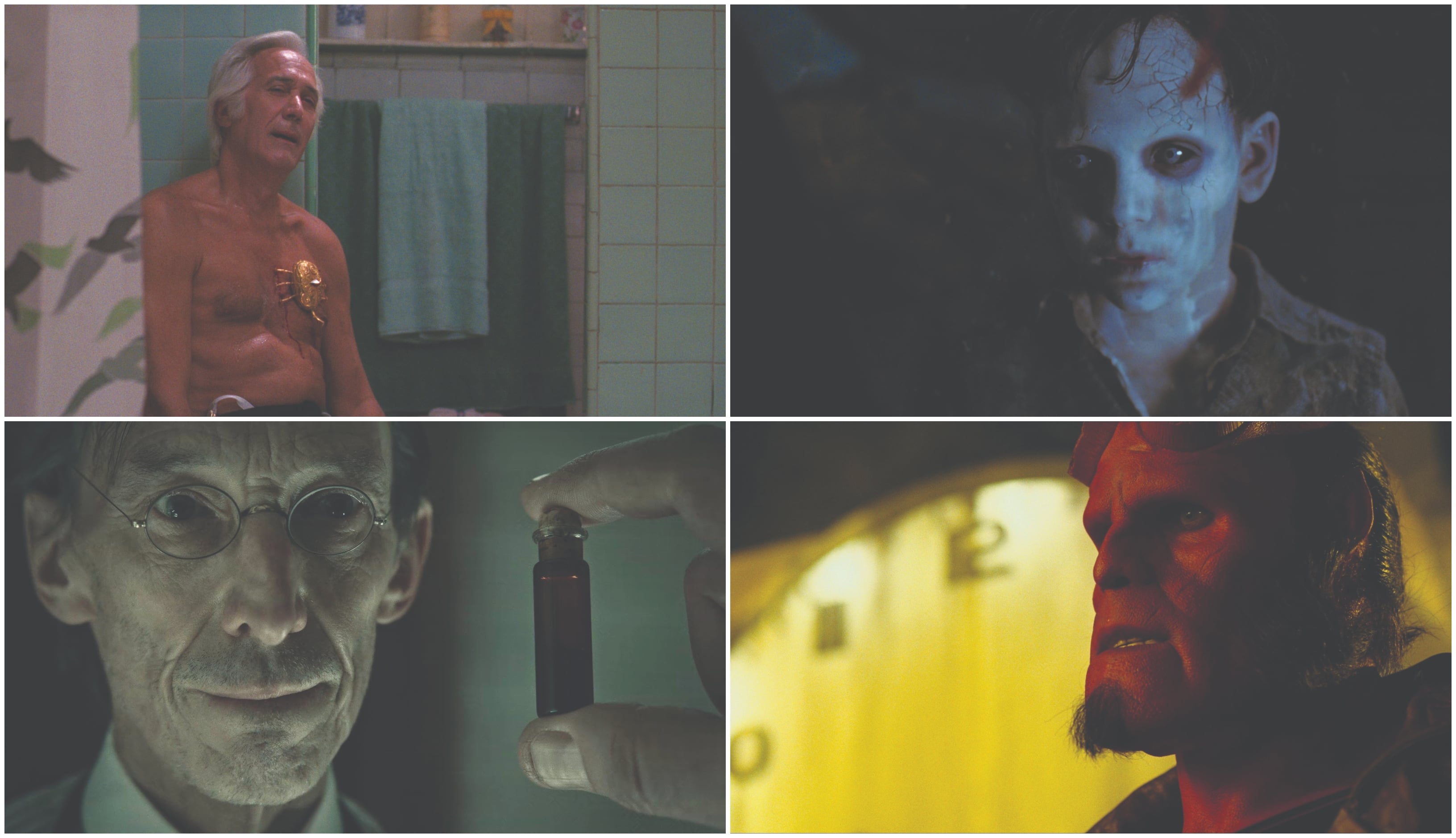

Visual paradigms have shifted throughout del Toro’s career, which is rooted in 35mm photochemical processes and has lately — namely, in the filmmaker’s most recent five features with Dan Laustsen — involved digital capture. “The moment we could color-correct digitally, the tools became very interesting,” he says. “We were able to maintain pure blacks and selectively affect different colors; that became very attractive to me. I remember we could only digitally color-time a few shots on Blade II, and then we were able to digitally color-correct the entirety of Hellboy. On Pacific Rim, the colors I wanted were almost like animation for their purity of color, so I knew we needed to start with digital. Since then, I’ve been on a quest with Dan Laustsen to emulate, as much as possible, a painterly effect that we find compatible with the digital format.”

Del Toro’s use of color is always symbolic and highly specific, and all departments collaborate to deliver a unified vision. “I don’t think any department exists on its own. To me, production design is cinematography, wardrobe is cinematography, [and] cinematography is both of those. And then, as a director, I dictate what each color has to mean [in] the tone of the film.”

He notes that the color red appears in Cronos only in connection with one character and with blood, symbolizing life; in Crimson Peak, it represents sins of the past; and in Frankenstein, it symbolizes Victor’s love for his mother and his boundless desire to conquer death. “We limited that color very stringently,” relates del Toro. “By the same token, each episode [in Frankenstein] has a color coding of its own, but we echo red through all the episodes.”

“Think Cinematically”

The artistic freedom del Toro now enjoys is enabled by the patronage of Netflix. “In my experience, Netflix has been a lifesaver. They gave me two of my bucket-list [productions] that I’ve pursued for decades, Pinocchio and Frankenstein, and they gave them to me with absolute freedom, in the scope I wanted, with zero creative interference and full support upon release.

“At the same time, there is no substitute [for] the theatrical experience. We were able to get three or four weeks of theatrical release on Frankenstein, and I hope that expands in the future. There is scope to that film that expresses itself better theatrically.

“You have to take into account two things. One, without Netflix, there would be no Frankenstein; I’m absolutely certain of that. And two, even if that film plays on TV, its ambitions are absolutely cinematic. I believe the importance of the size of the screen is equal to the size of the ideas. You have to think ‘cinema’ and hope [your work] can be shown mostly in cinemas. But the first thing is to think cinematically.”

Del Toro’s upcoming slate is varied and full. “I’m working on my second stop-motion animated feature, based on The Buried Giant by Kazuo Ishiguro. And I’m working on a crime thriller using different storytelling tools than I normally use, meaning I’m going to try to make it less operatic and a little more immediate and raw. I’m trying to find a different language for myself.

“The only advice I can give to somebody breaking [into the business] is: The only thing you have different than anyone else is your voice. Be true to that, and try for the movies to mean something to you.”

He adds that the ASC Board of Governors Award resonates with him strongly. “This cements an intimate relationship between the disciplines that the ASC fosters and guards and the discipline and craft of directing. I happen to be a believer in the creation of images that are of a certain scale and done with a handmade pride. That would not exist without the relationship between director and cinematographer. For the fact that the ASC recognizes that, this award means the world to me.”

A Lauded Career

Guillermo del Toro’s accolades have often straddled the Americas. His first feature, the genre-bending Mexican vampire fantasy Cronos, won the Golden Ariel for Best Picture and eight Silver Ariels, and his dark period fairytale Pan’s Labyrinth (AC Jan. ’07) won the Golden Ariel for Best Picture, eight Silver Ariels and three Academy Awards, including one for cinematographer Guillermo Navarro, ASC, AMC, a longtime collaborator.

In 2018, del Toro won Oscars for both Best Director and Best Picture for the romantic creature-feature The Shape of Water (AC Jan. ’18), which he followed with another Best Picture nominee, the gothic Depression-era drama Nightmare Alley (AC Jan. ’22); both were shot by Dan Laustsen, ASC, DFF, his cinematographer of late, who received Academy and ASC Award nominations for each. In addition, del Toro won the Oscar for Best Animated Feature for his stop-motion production of Pinocchio, shot by Frank Passingham, BSC and co-directed by del Toro and Mark Gustafson. The feature Frankenstein now sees both del Toro and Laustsen nominated for Academy Awards (and Laustsen for another ASC Award).

His kaleidoscope of films has so far encompassed 13 features and three television series. The films have ranged from the comic-book extravaganzas of Hellboy (AC April ’04), its sequel, and the giant robot/kaiju wars of Pacific Rim (AC Aug. ’13), all shot by Navarro, to more introspective gothic fantasies such as the misunderstood ghosts of Crimson Peak and the vagabond Creature of Frankenstein. His television work includes FX’s parasitic body-horror series The Strain, adapted from a novel he wrote with Chuck Hogan, and the Netflix/Dreamworks Animation CG-animated series Trollhunters: Tales of Arcadia, based on a novel he co-authored with Daniel Kraus. Del Toro also created and hosted Netflix’s Rod Serling-inspired anthology Guillermo del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities, a showcase of horror and cinematographic talents that resonated with his distinctive flavor of operatic fantasy.