Jack Pierce — Forgotten Make-up Genius

The man behind the classic monsters played by Karloff, Lugosi and Chaney Jr., this creative artist has seemingly been lost to time.

This article originally appeared in AC, January, 1985.

“Jack Pierce?” The clerk at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Margaret Herrick Library asked with a quizzical expression, “I don’t think we have a file on him. What did he do?”

Advised that he was a make-up artist, the lady retorted, “I know we don’t have anything on him. What were his credits?”

Nothing much, Frankenstein, The Bride of Frankenstein, The Old Dark House, Son of Frankenstein, The Mummy...”

“Oh.”

A 10-minute search produced a nearly empty envelope with the name Jack Pierce typed on the front. It contained two obituary clippings from the trades, one dated July 23, 1968, the other July 25. The entire career of a movie genius was tersely summed up in eight inches of repetitious biographical information. By contrast, the files on two of Pierce’s frequent subjects, Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi, spilled over into several thick envelopes.

The Universal Studios Research Library had a better file on Pierce, but it continued little that was new, mostly faded news clippings from the 1930s and more obituary material. “We don’t have much,” the librarian admitted, “He left here a long time ago, about 1945, I think. I wish we had more. He was a very interesting man.”

At the offices of the Make-up Artists and Hair Stylists, the story was the same. “Of course we knew what he had done,” Howard Smit, the business agent said, “but I don’t know of anyone who worked with him who isn’t dead now. He wasn’t an easy person for anyone to know.”

Following the fading trail of the legendary movie figure continued for almost two decades. It had all started in 1968 while I was a publicist at Universal. Not knowing the history of his abrupt departure, I called and tried to set up an interview with Jack Pierce himself.

All went well until I mentioned that I worked for Universal. That ended our conversation. Pierce could hold a grudge and he was stubborn.

Pierce wasn’t singled out for obscurity, it was just the way Hollywood treated most of its founding fathers and patron saints.

Six months later, I joined 23 other mourners trying to fill two rows of pews at his funeral. It was a hot day and the minister tried to eulogize a man he knew almost nothing about. Wandering from thought to thought, the preacher sputtered prayers and scriptures until he could keep up the charade no longer and sat down. Three make-up artists attended, plus several people from the fringes of make-up who made monster masks based on Frankenstein and other Pierce triumphs. It was pathetic.

Pierce wasn’t singled out for obscurity, it was just the way Hollywood treated most of its founding fathers and patron saints. They weren’t missed when they were alive, and still fewer missed them when they were gone.

The historian in me refused to let the story end with a bleak funeral and I continued my quest until I reached Boris Karloff. Like his former make-up man, the star was in the twilight years of his career. He was in Hollywood for a short time making a film called Targets and consented to be interviewed about his days with Pierce and the creation of Frankenstein.

A worshipper of the actor from afar, I was eager for a chance to meet and interview one of the most famous film stars of all time. I am sure that for his part, Karloff was less than eager to submit to another interview, but gracious man that he was, he consented.

From my interview, I came to realize that Frankenstein was a film born out of desperation, created by immigrants who were all trying to remain in the film business at a time when the general economic climate was decidedly against them.

“Uncle” Carl Laemmle, head of Universal, had reached a point in production that required money, and fast. The studio, despite the success of All Quiet on the Western Front, was struggling to stay out of the hands of bankers and other financial interests.

Carl Junior, who loved horror movies, sold his father on Dracula and then convinced the elder Laemmle that Frankenstein would be another good bet. A former haberdasher from Germany via Oshkosh, Wisconsin, Carl Laemmle, having no desire to go back to selling clothes, agreed to the adventure into horror films. The director selected, James Whale, was from England where he had had great success with stage plays. After coming to Hollywood he was the dialogue director for Hell’s Angels, then directed the film version of his hit play, Journey’s End. None of this had yet provided him with the kind of reputation he needed in Hollywood to obtain steady employment.

Junior Laemmle had asked Bela Lugosi to screen test for the part, but the latter failed in his attempts to bring shivers to the spines of studio executives. Exit immigrant number one.

Karloff was enjoying a brief employment as a murderer in a Universal picture titled Graft. Whale noticed the distinguished-looking actor and invited him to test for the part of the Monster. Work in Hollywood was scarce, and Karloff freely admitted later that the discovery that his face would be almost wholly covered with the yet-to-be-designed makeup gave him only a moment’s pause as he eagerly assented to the proffered screen test.

In later interviews, Whale cited the “strong facial structure” of Karloff as the reason for his initial interest in the actor. The fact was, however, that Whale himself was quite insecure. In England, where he had been an important stage director, his abilities were known and appreciated. On coming to Hollywood to work in films, things were different.

When Whale, “the most important director on the lot,” as Karloff styled him, embarked on his Frankenstein project, he was clearly in need of emotional “props” and he sought them in the form of fellow British expatriates such as Karloff, Colin Clive, and, later, Elsa Lanchester, among many others.

Hence the fact that Karloff was chosen to try for the role likely came about as much from the fact he was English as from the fact he had started to build a strong reputation for himself as a “heavy” in gangster films and had “strong facial structure.”

With the promise of a screen test, Karloff fairly floated to the studio make-up department where he met Pierce for the first time. A small, wiry man with a quixotic imagination and a sometimes sharp-edged temper, Jack P. Pierce was an immigrant from Athens, Greece who had spent two decades working his way upward in the film business to his present position of head of the Universal make-up department.

His job was reasonably secure, but he longed for the authority over actors that would allow his latent abilities as a technical artist full expression. He was still smarting over the rebuff he had received at the hands of Bela Lugosi, first in Dracula, where he had suggested some dramatic additions to the star’s face for the role, and later for the Frankenstein screen test.

Part of the difficulty between Pierce and Lugosi stemmed from the star’s aversion to have anything other than a light coat of greasepaint on his handsome features. He did allow Pierce to blend a special light green tone for Dracula which, when photographed in black-and-white, gave a ghoulish pallor to the vampire’s visage.

With the screen test for Frankenstein, Pierce had elaborate suggestions for the Monster’s makeup, and again he was given a prompt “no” by Lugosi. By the time Karloff appeared, ready to submit to anything in an effort to get the role, Pierce was in a complete temper fit.

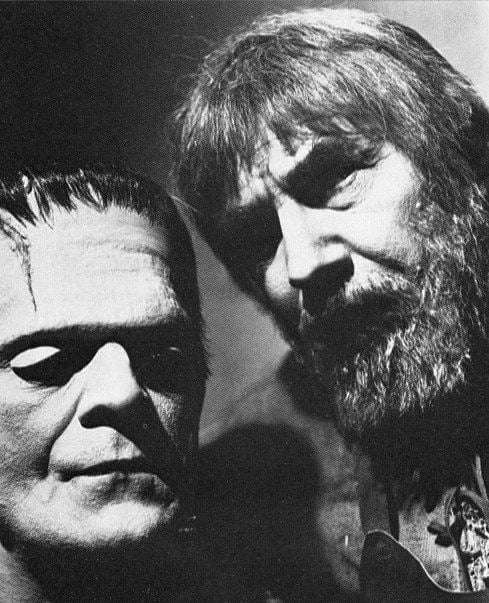

There seemed to be an immediate bond between the two men, which partially centered on the fact they were both immigrants. But there was another element: Karloff was pliable and anxious for Pierce to help him. This attitude put the make-up man in the driver’s seat.

That was all that was needed for something remarkable to transpire.

A life-long friendship and it might be said, mutual admiration society was formed before the actual design work on the Monster even started.

Despite the fact it was the movie Monster that brought the principal characters in the Frankenstein saga together, it is likely it would have become another Universal “pot-boiler” if each person had not possessed the insight and motivation needed to make the film a genuine classic of Gothic terror.

Whale was using British actors to tell an English Gothic tale, struggling as he did so to create his own screen technique and interpretation that would take him on to more serious projects; Karloff was trying to stay employed and was eager to be the Monster. Pierce for his part was waiting for a chance to prove his abilities as a visual artist with make-up and ingenuity. Junior Laemmle was excited at the prospect of giving birth to yet another horror film in the tradition of his successful Dracula and his father, “Uncle Carl” was looking for a quick fix for his financial troubles.

During the tedium of creation, as Pierce tried first one idea, then another, searching for the combination that would bring his vision of the Frankenstein creature to life, there was plenty of opportunity for the two men to discuss a variety of subjects. But one that received scant attention, was the past history of Pierce.

Aside from a few sketchy details, such as Pierce starting his career in a movie projection booth about 1910, and that he had been a professional baseball player and later a film actor in silents, there was little new information.

Pierce was respected at Universal as a professional who could handle anything the studio could toss in his lap, but his reputation among others in his craft was slight. He didn’t work at the great movie factory, MGM, where the reigning “kings of make-up” were ensconced. Instead, he was head of a tiny department at a second class studio.

Even at Universal where he was respected, there was a thorn in his professional side — Lon Chaney, the legendary “Man of a Thousand Faces.” Even though the star was dead, his glittering reputation still hung over Pierce like a shroud. Everything Pierce did was compared to what Chaney might have done in the same situation. How close this relationship between Chaney and Pierce was can be gleamed from an interview I conducted with Joe Rock, an independent producer at Universal during the early 1930s.

Rock won an Academy Award for his documentary Krakatoa and was very popular on the Universal lot. He was also a member of the studio basketball team which was sponsored by Junior Laemmle and coached by Pierce.

If Pierce had a hobby, apparently it was the team, for a number of photos survive that show him posing with the various groups, those that traveled out of town as well as the local matches. Because they were so friendly on the courts, Rock came to know Pierce very well. “He was the most wonderful man in the whole world, what more can I say?” the retired film executive asked.

As the interview progressed, something popped out that created a fresh mystery about Jack Pierce. “I know he was working on special make-up for Lon Chaney,” Rock mentioned one day, “that I know for sure.” Chaney was a very secretive person, especially when it came to various techniques he used in his film roles. He once made the statement, later confirmed by his son, Lon, Jr., “I will take most of my makeup secrets to my grave.” He insisted on doing his own make-up, even in his early career when no one knew the amazing talents he possessed, so why at the height of his career, before his tragic death, would he turn to Jack Pierce?

Rock had no answer. “All I know is it was special make-up just for Chaney. Jack was very proud of himself for being involved with it.”

Try as he might, Rock has been unable to fill in any more details on this sidelight of Pierce and Chaney. Possibly Pierce was bragging about his abilities as a make-up artist in front of his friends, where he could be sure of not being questioned as to specifics. Or was he really working on some unusual makeup creation that required his special talents? Unless further information comes to light, we will never have an answer.

One thing that does seem clear from later events was Pierce’s determination to do something with the Frankenstein Monster that would eclipse the previous triumphs of his former competitor. So a new element enters the development of a Frankenstein Monster: professional ego.

Karloff would have been oblivious to the overtones present at the creation of his makeup. He did say that Pierce was a studio “insider” and because of this position, he was able to stall requests for the screen test a number of times, thus preventing its premature exposure to Whale, or the Laemmles.

Thanks to the rapport that blossomed between the two men, no trace of Pierce’s temper fits and abrupt, austere manner was evident during the long sessions required to fashion the Monster’s makeup. Had it been the other way, chances are good the Monster would not have become the spectacular success it was.

“He was nothing short of a genius, besides being a lovely man,” Karloff said once. Karloff had long felt he had never been given a role that allowed him to use his acting talents to the fullest. Pierce, on the other hand, felt the sting of rejection frequently when he tried to consult with the Universal roster of stars since he was “only” a make-up man. Now the two men faced each other, probably realizing in some subconscious way, their moment had come.

What would the Monster look like?

Time and time again this question had surfaced, only to go unanswered. When he was first suggested for the role, Karloff had purchased a copy of Mary W. Shelley’s novel and read the description of the creature that emerged from Dr. Frankenstein’s laboratory. He quickly realized, as Pierce had before him, there was no explanation in the book that could help them.

The fact that Mrs. Shelley didn’t go into detail about the Monster was probably a key element in the drama now taking place in the Universal make-up department. Since no literary blueprint had been prepared by the author, Pierce with suggestions from Karloff would be free to let their imaginations go wild. This was an opportunity that might never come again and Pierce was ready to seize the moment.

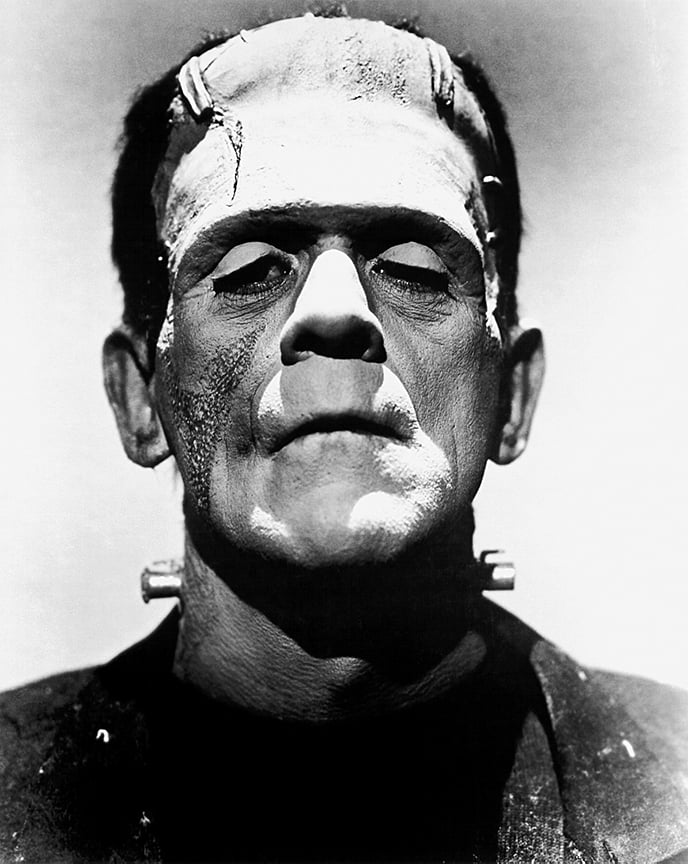

In the half-century since Frankenstein appeared on the screen, no dichotomy has erupted over the interpretation. In one final, hold stroke, Pierce gave the world the definitive expression of a freak that had slumbered in the imaginations of men for more than a century.

A cloak of secrecy was thrown over all aspects of the Frankenstein project. Pierce and Karloff kept their counsel until the screen test. Universal kept prying eyes away from the set until the movie was completed, then refused to talk about it until its official preview screenings which set Hollywood and later the rest of the country buzzing with excitement.

Like his literary counterpart, Dr. Frankenstein, Pierce and his co-conspirator created their version of the Monster piece by piece in a midnight laboratory — an old dressing room far from the prying eyes of studio executives. For Pierce, the idea of working furtively was appealing; he wasn’t anxious to let anyone, even assistants share in his “trade secrets.” In this he was much like Chaney. Both men felt their collected wisdom shouldn’t be shared, only exploited by themselves.

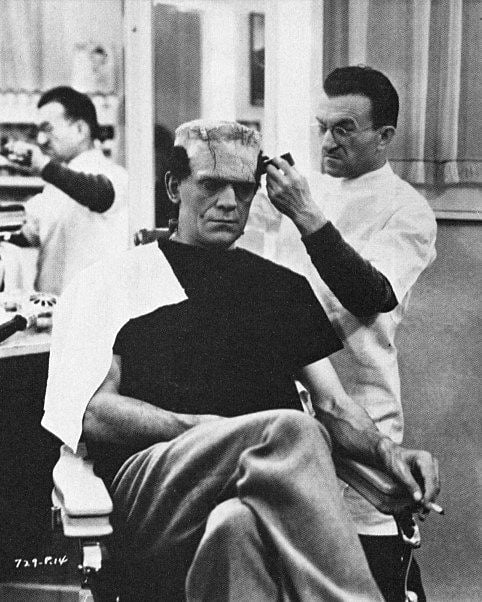

In the late 1930s, when the issue of Frankenstein had become a somewhat tiresome theme and the public had real monsters to worry about, Pierce gave an interview in which he described the many months he had spent researching the creature he was going to bring to life with make-up. All of this begins to sound a bit odd however, since Karloff said in oft-repeated interviews about the original articulation of the makeup that he would leave the set of Graft at the end of the day’s shooting and go to the place where Pierce was waiting. After bolting down a quick sandwich and cup of coffee, and having a last cigarette, Karloff would settle down in the barber chair for the night’s work.

When asked if they had worked on the concept and manufacture of the Monster’s face for months, Karloff responded: “Heaven’s no! We were working like fiends [chuckle] to get it done before someone changed their mind and we lost the opportunity completely.”

During this period, the studio production office would call repeatedly asking if the project were done so that the screen test could be made and each time Pierce would deftly shunt them aside. “No, not ready yet.”

The make-up fabrication did take a long time, but not months, as Pierce liked to say.

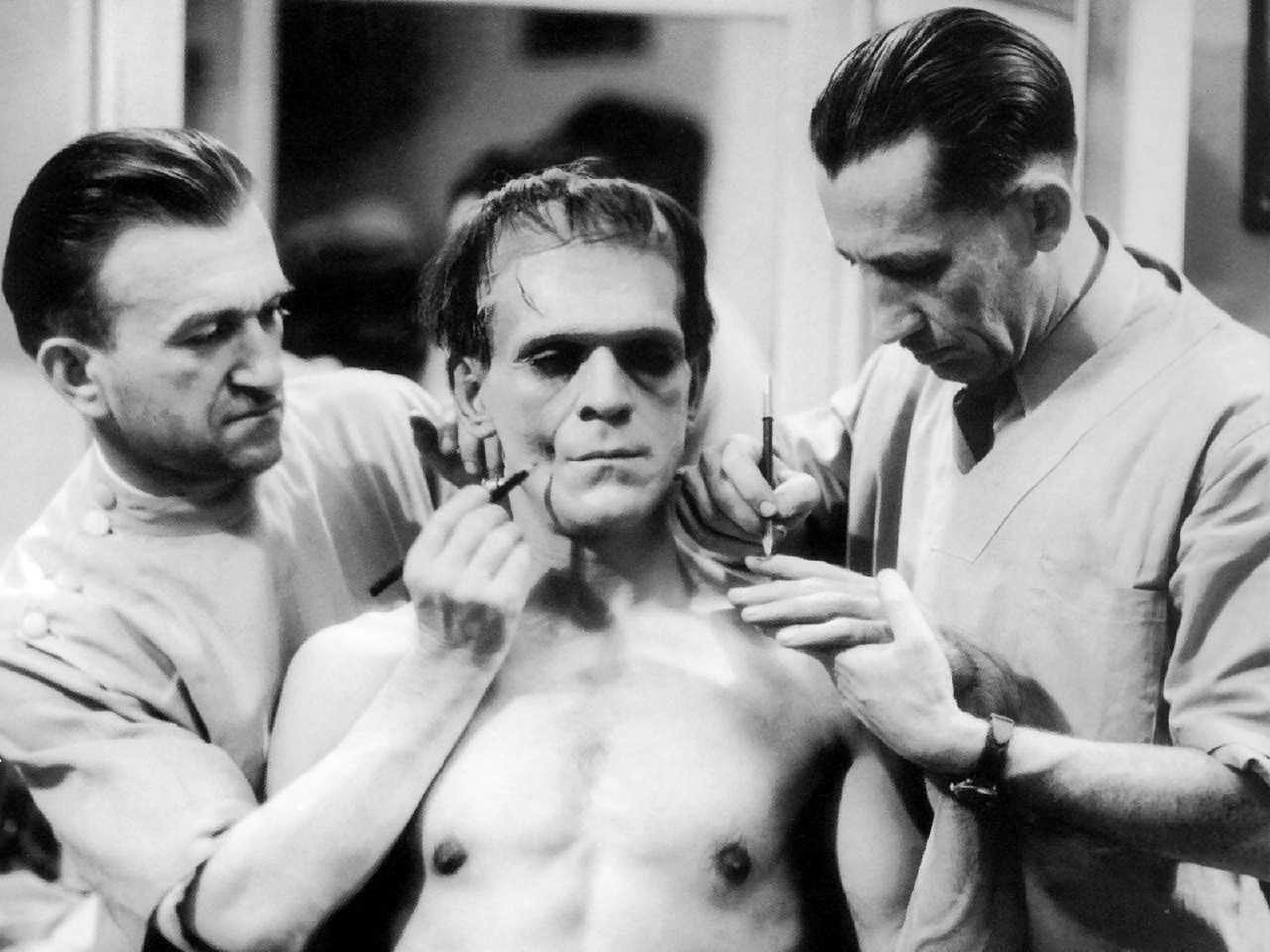

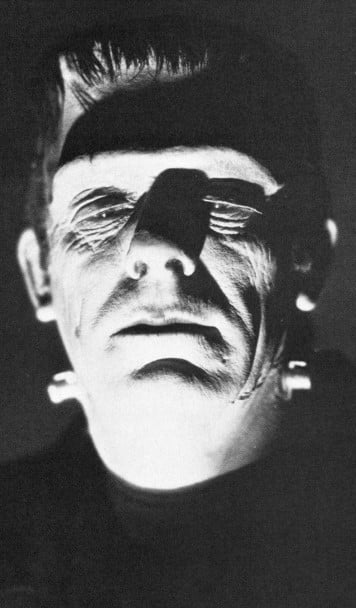

That the face that emerged at last from the make-up lab was immortal, no one can dispute. From the flat-topped dome, to the scars and neck plugs (which left permanent scars on the actor’s neck), everything was perfection.

In one of his few interviews, Pierce explained that he had consulted a medical book that said there were six possible ways to cut open the human skull, he elected to use the simplest one, a straight cut that removed the whole top of the head. With this procedure, Dr. Frankenstein could plop in a new brain, snap the “lid” on with metal clamps and his creature was ready for an infusion of lightning.

To make the squared-off skull contour, Pierce literally built a new head on Karloff with layers of cotton and alternating applications of collodion, (a flammable chemical which denied Karloff the pleasure of smoking while the work progressed).

Karloff admitted he lost track of the number of hours he submitted to the physically draining experience of sitting riveted to the seat of the make-up chair, almost motionless as the whole weary process ground on:

“After a hard day’s shooting on Graft, I would spend another six or seven hours with Jack, then return bright and early for the next day’s shooting. More than once I wondered if my patience would be rewarded with a contract to play the Monster.”

In that pioneering era of motion-picture production, there was no way known to cut short the process that Pierce used to make the Monster’s face. Karloff would stop short of saying that the make-up was painful, in deference to his friend’s feelings, but it was. He was just too much of a gentleman to reveal the full extent of the misery he suffered.

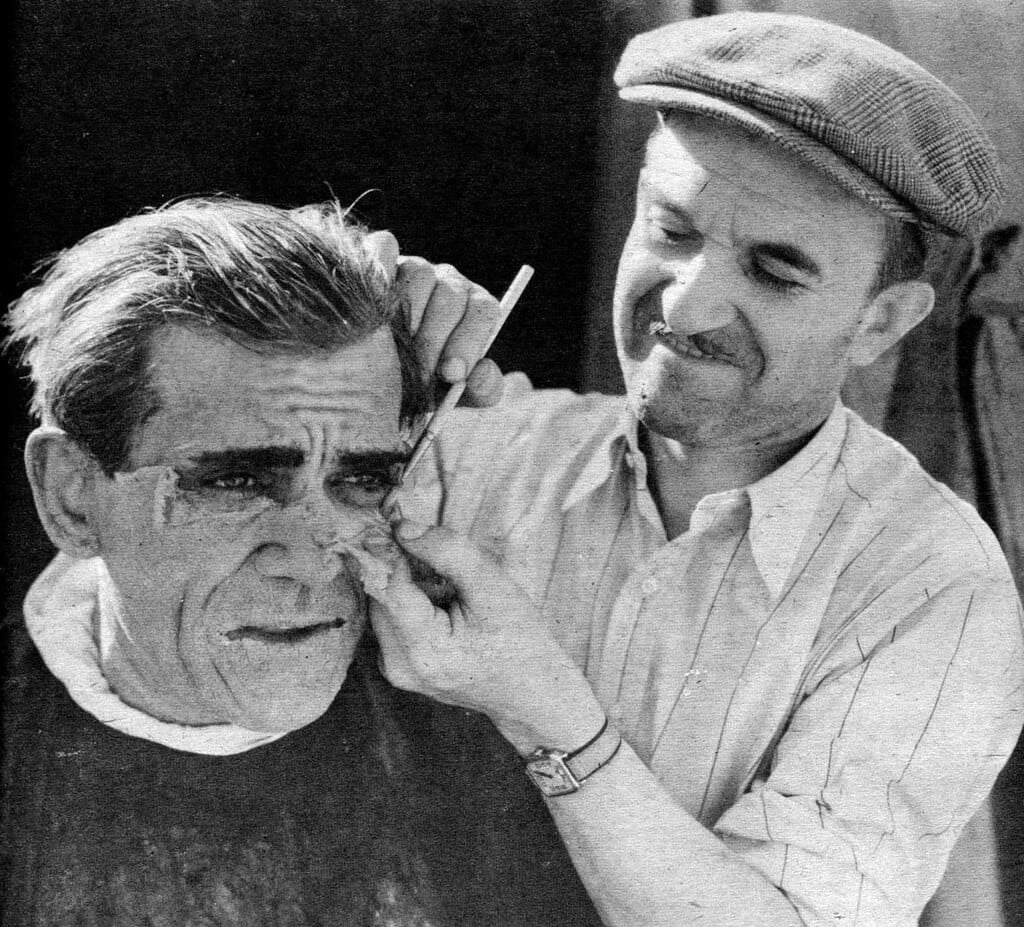

In common with other craftsmen of his day, Pierce was using materials that wouldn’t have been out of place on the shelf of a medieval alchemist’s den. A few had been used in stage make-up for years. Despite their crude nature, Pierce was a master at blending them and making an illusion so perfect, the all-seeing eye of the camera couldn’t spoil the effect by revealing flaws.

The heavy, drowsy eyelids that gave the Creature a half-alive look that audiences loved, were first made out of wax and attached to the actor’s own. Later these were replaced with false lids made of rubber. For the 1939 sequel Son of Frankenstein, a rubber dome was made, but there were few other shortcuts during the many months various Frankenstein sequels were in production. Everything was hand-made in the truest sense of the word.

For the pallor of death, Pierce revived one of his ideas for Dracula and mixed a special greasepaint which photographed grey on the screen. Hand-painted applications of fresh scars, careful shadow definitions, coarse, matted hair and other theatrical touches brought the living corpse fresh screen impact.

The towering size of Dr. Frankenstein’s Monster was accomplished by the manufacture of special shoes (weighing 30-pounds each) while Karloff’s legs were encased in metal struts that wouldn’t allow the knees to bend. Two pairs of trousers were then added to pad out the figure. Pierce shortened his friend’s coat sleeves to make his arms look longer and black shoe polish was added to the finger tips to make it look as though blood had collected and dried in those extremities. Added together, the touches of scientific fantasy and showmanship gave the Monster a foreboding presence.

Once the Monster design was finished and Karloff was officially cast in the role, the worst part of the ordeal began for the star. He was packing 6o pounds of costume, struts, shoes and miscellaneous accouterments, plus make-up that was uncomfortable at best, and miserable under certain conditions. Under the blazing outdoor sun on location or in the sweltering, overheated sound stages, 10, 12, sometimes 14 hours per day, he struggled on. It seemed at times that Whale had a vengeance against the Monster that he was taking out on Karloff.

Time after time, the director demanded that the actor carry a limp Colin Clive up the hill to the old mill. Loath to refuse, Karloff did as he was asked, but the strain on his back sent him to the hospital shortly afterward for a fusion. Karloff never felt that Whale was trying to punish him personally, but he frequently was sure the Monster was being punished by the British director, and he started to resent the treatment.

The final hours of torment came at the close of shooting each day when the Monster’s face had to be removed. This session usually lasted up to two hours and was fraught with more misery as the applications of cotton, grease-paint and collodion were dissolved with powerful chemicals. The plaster used on his hands and wrists would remove Karloff’s body hairs, adding to the discomfort.

Bits of the make-up fell into his eyes, adding to his list of film-related injuries. More than three years later, tiny white scars remained on Karloff’s chest where bits of hot carbon from the movie lightning had rained down on him during the scene in which the Monster is brought to life by Frankenstein. Laemmle Jr. said, “Karloff’s eyes mirrored the suffering we needed.” For the thespian’s part, not all of the suffering that so delighted Whale and Laemmle was acting.

That the total Frankenstein experience left deep scars on his psyche was evident during our short interview, when the aging star would pause and shudder slightly at some of his recollections.

By the time Karloff and Pierce did Son of Frankenstein, eight years later, in 1939, the make-up man had refined some of his techniques with substances described as “plastics,” but the total ordeal was hardly shortened.

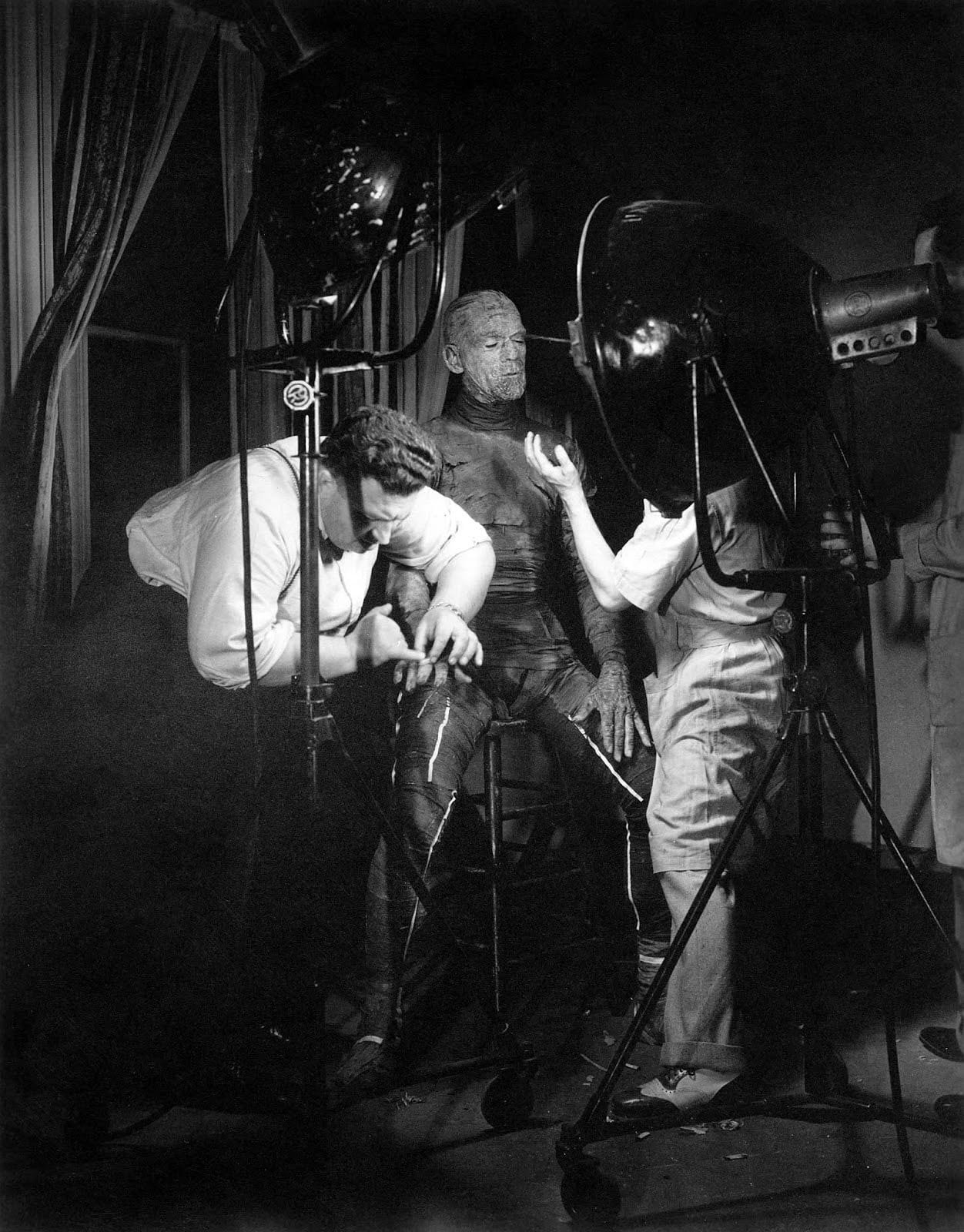

The Mummy, produced in 1932, teamed Pierce and Karloff again and the result was another triumph of technical skill and visual artistry. But if Karloff thought he was to get a respite from the rough physical treatment he had endured in Frankenstein, he was in for a shock.

The mummy wrappings developed for this picture consisted of linen that had been boiled until it literally fell apart in Pierce’s hands as he applied the strips of cloth. Karloff’s disguise required layers in three directions, (horizontal, vertical and diagonal) to cover his bare skin and Pierce had a tough time of it.

After the wrapping was completed a thin coat of clay was applied. Next came glue. The face and hands received a brilliant application of Pierce’s best makeup art. Cotton was stuck to the actor’s face and hands with adhesive, with the extra bits of the former removed with tweezers. This gave the skin surface an irregular effect. Next came an application of grease-paint that gave the cotton a tone that matched the bandages. A dark brown pencil line was used for final accentuation and modeling under the “brute” lights.

As the cotton dried, it tended to wrinkle the actor’s own face, highlighting the total effect. Next, Karloff’s legs were bound together and bits of rice paper were fastened to his eyelids. A small slit was cut in this for vision and the opening was accented with a grease-paint pencil to make it look as if the eye was half-opened.

The actor’s own thick hair was painted with greasepaint of a neutral color, then Fuller’s earth (used in paint manufacture) and beauty clay were mixed in. The effect was terrifying to audiences of the early 1930s who had been unused to such realistic special effects in horror films. When the mummy began to breathe and stir ending a centuries-long slumber, the wrappings burst from the surface stress and tension provided by the glue, and a light cloud of dust floated in the air.

It was one of Pierce’s best efforts.

But time was his enemy. This makeup took eight hours plus to apply and then two hours to remove. Slicing 10 hours out of a shooting day doesn’t leave much for the actor or the production company to work with.

For Pierce, there was no easy way. Everything he attempted was done the hard way since he had learned his craft that way and it was too late to change. The results were incredible, but modern film schedules and soaring production costs were pushing his genius aside.

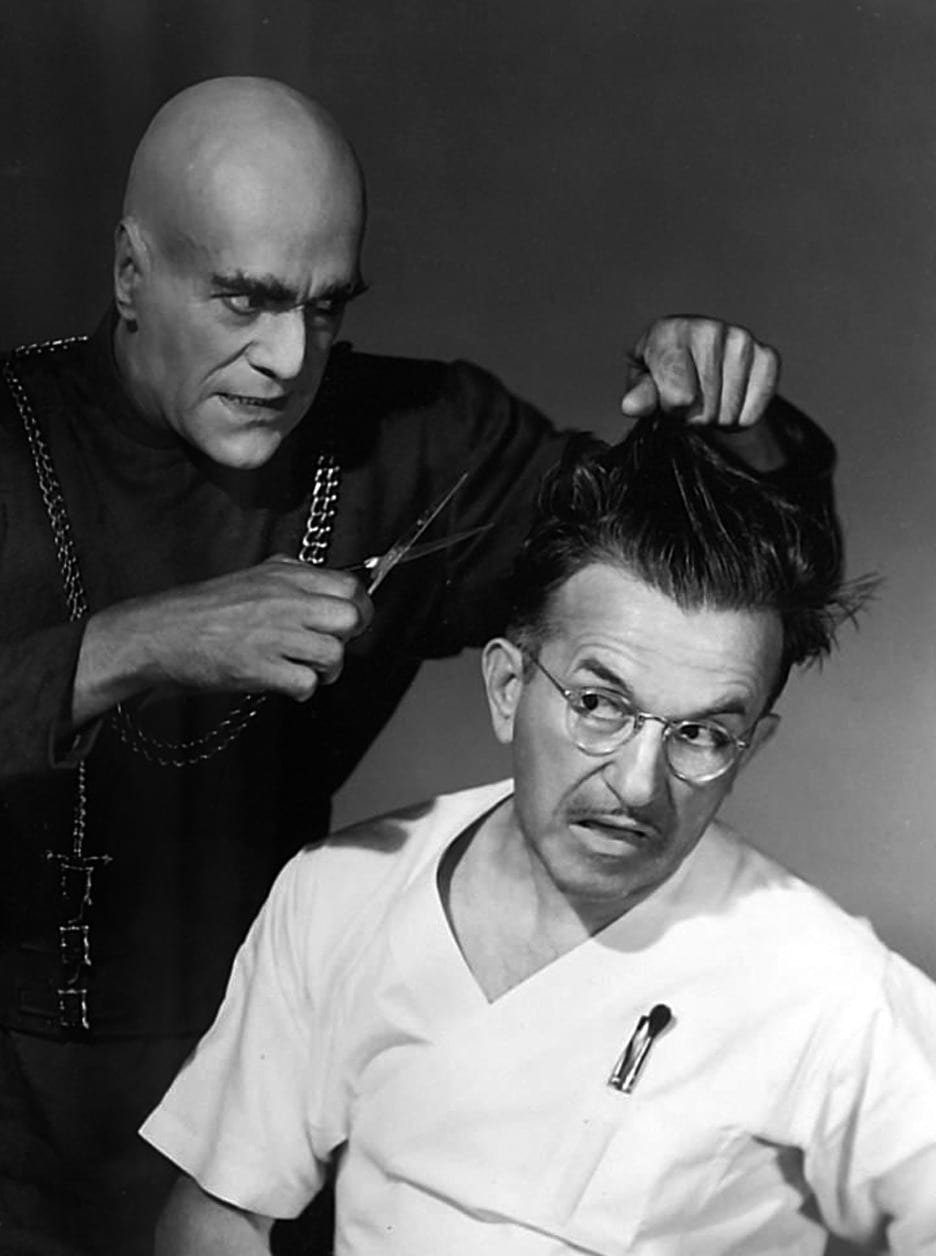

Bela Lugosi saw film roles fading and demands for his services in important films diminishing. When he was cast as Ygor, a criminal, in Son of Frankenstein, the Hungarian actor came to Pierce and asked for help in reviving his faded career.

If Pierce held a grudge, he didn’t show it. He promptly made a rubber neck for Lugosi that simulated the broken one the script called for, and then fashioned the rest of the make-up with yak hair. The star meekly submitted to this ordeal, (which was a good way to describe the four-hour make-up application). Gone were the days when Pierce was allowed to mix greasepaint for the actor and nothing else.

But, like Karloff, under the makeup, Lugosi came “alive” in the role and his superior acting and voice inflections proved once again he was a major film personality.

If Pierce saw the handwriting on the wall, it wasn’t apparent. With Karloff gone, Pierce and Universal entered the 1940s with Lugosi and Lon Chaney Jr. in their horror film ranks.

By this time, Pierce should have been in professional heaven. He had exorcised the ghost of Lon Chaney Sr.; now studio heads and his peers in make-up pointed to his accomplishments as benchmarks of perfection.

Universal needed a new Monster. Karloff had made it plain that he was not coming back to play the part under any circumstances, feeling there was nothing more he could do with the role.

Enter The Wolfman.

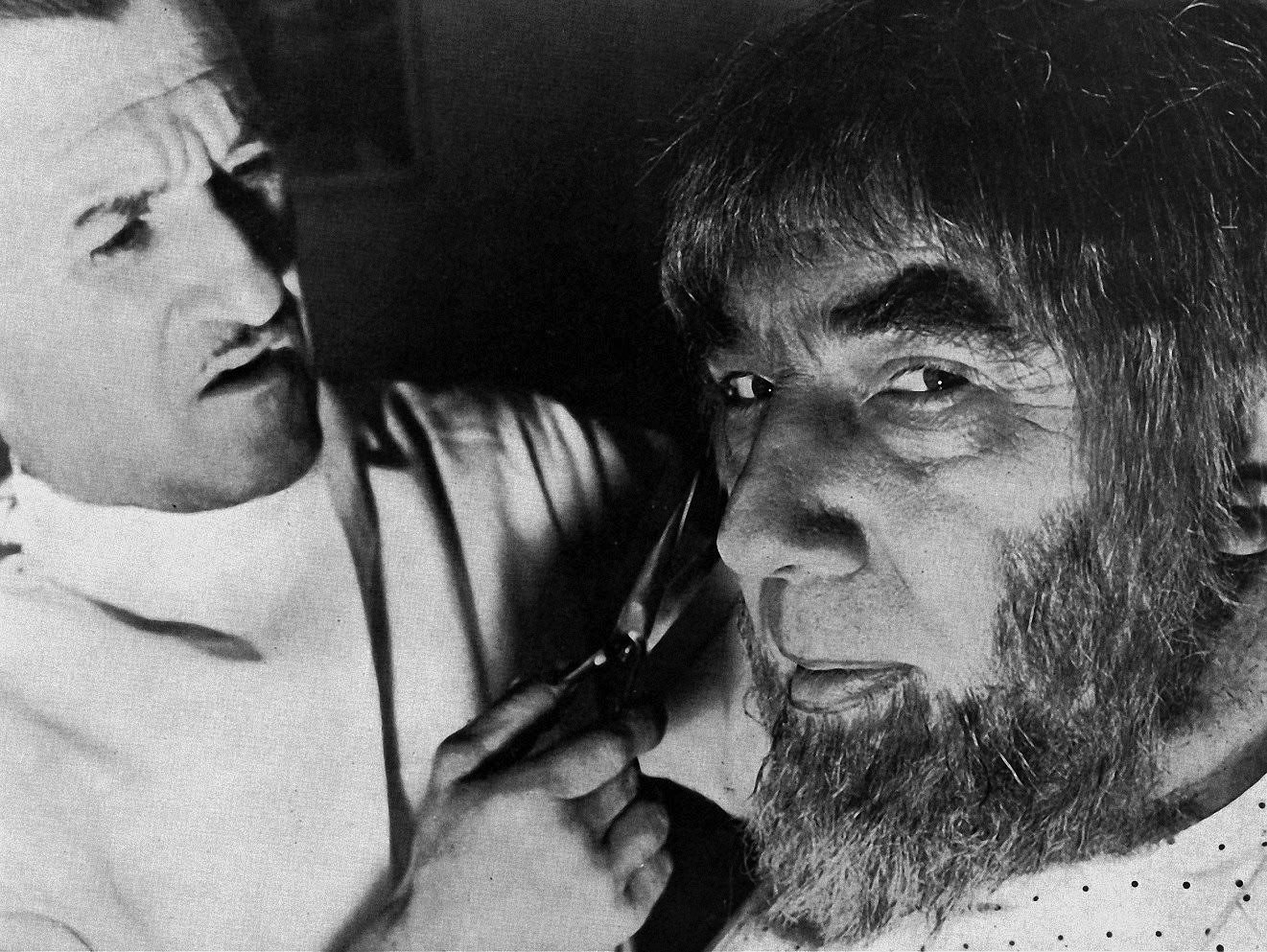

Lon Chaney Jr. was a large fellow, imposing in size with strong features. He was the ideal vehicle for a menacing film freak. Working with Chaney as he had done with Karloff, Pierce devised a wolf face that would, like his other creations, become a classic horror personality.

Making a rubber snout, Pierce applied hair to the actor’s face in a laborious process that sometimes consumed 16 or more hours. A transformation could take up to 22 hours. While studio heads watched the clock tick off the hours, Pierce would go about his painstaking makeup procedures.

The effect on the screen was marvelous, but the manufacture of the effect pushed the costs of the low-budget features even higher. Pierce was unsympathetic to the virtual log jams he was making in the film output of Universal. Perfection was his goal. To demands that he speed things up, he seemed to be saying “Let them eat pancake.”

One of the most effective parts of The Wolfman (1941) was the on-camera transformation of Chaney into the werewolf. The process involved careful cooperation between cinematographer John P. Fulton, ASC and Pierce, plus a number of other departments, to successfully pull off.

A set would be constructed, such as a window with the moonlight pouring through. Chaney would stare at the moon as he slowly metamorphosed into his monster role. Nothing could move during this process to reveal the stop motion tricks of the camera operator. The background curtains would be starched, Chaney would hold himself rigid, and the camera itself would be weighted to prevent vibration.

As Chaney gazed toward the sky, Pierce would start by putting a few hairs in place on the actor’s face and hands. The camera would roll, more hair would be added and so on. When the time came for a new nose on Chaney, everything would stop, a glass plate would he swung into place next to Chancy’s head and his outline drawn on it.

Retiring to his lab, Pierce would complete the next stage of the makeup and return Chaney to the set. He would he re-positioned against the glass outline, and the sequence finished. Between Chaney’s drinking problems and Pierce’s slow make-up applications, nearly a full 24-hour period would drain away — more if the actor grew impatient and ripped the make-up off mid-way in the shooting.

By 1945, no one at Universal could justify the combination of a prima donna make-up man and star.

Universal was not making works of art, they were making “B” movies that had a short shelf life (or so they thought at the time), so speed, low costs and simplicity were their gods. Aging, slower than ever, more demands in his requests for time to do his work, Pierce was shown the door in 1945 after The House of Dracula, another pot-boiler thriller.

The war had ended; younger men, eager for work were clamoring for a chance. Trained in the use of latex and techniques developed by the medical profession to help injured veterans, they pushed their way into the studios with fresh ideas and an urgency unknown before. The truth was plain. There was no longer a place for legends, no matter how great. The film business was going to move forward with younger talent, men and women anxious to prove their skills and talents.

Stubborn to the end, refusing to compromise or use cost-cutting techniques, Pierce was essentially let go after 22 years of devoted, brilliant service. When told that the make-up quality would suffer, a studio executive said, almost with a sneer, “So the make-up isn’t perfect. People are still buying tickets; that’s all that counts in this business.”

Pierce freelanced at the old Hal Roach Studios for a time, and did some amazing makeup on the TV show You Are There. But the glory days were over. The slow decline was one of infinite emotional pain for Pierce, because he still lived in the shadow of Universal, the site of his early screen triumphs. He could watch the work of younger men like John Chambers (who won an Oscar for another science-fiction classic, Planet of the Apes [AC April, 1968], the same year Pierce died) and ruminate on the vicissitudes of fate. No film societies clamored for his lectures, no star was cast on Hollywood Blvd., he wasn’t searched out for interviews; his eclipse was complete.

Almost 16 years after his departure from this world, no books have been written about his accomplishment, although Pierce is mentioned prominently in a number of reference works. There is little to remind the world that he was once the greatest horror make-up man Hollywood had ever seen. A tribute of sorts is still found to his special genius each time one of his monsters is flashed on a screen, so his memory in that respect is maintained in perpetuity.

Jack P. Pierce may have taken inordinate amounts of time to create his make-up with the crudest of old-fashioned materials, but no one ever did it better.

He was one of a kind.

Thirty years after the publication of this article, the documentary Jack Pierce, the Maker of Monsters was released in 2015.

For access to more than 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.