Kingpin Rising: Snowfall

Cinematographers Eliot Rockett and Tommy Maddox-Upshaw give AC a look behind the scenes of the tension-steeped FX series.

By Fred Schruers

Photos by Ray Mickshaw and Prashant Gupta. All images courtesy of FX.

Few enterprises can stage an invasion of a neighborhood quite like a location shoot can, and today on the placid streets of the Lincoln Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles, just a few miles northeast of the city’s downtown center, the takeover is in full force as makers of the FX series Snowfall capture the penultimate episode of Season 3. The LAPD has set up a traffic-coned perimeter, closing normally busy Workman Street where it meets Avenue 26. Ranks of trucks, emptied of gear, clog nearby blocks. Director Ben Younger — who made his mark via such indie features as Boiler Room — has been overseeing a brisk pace to complete a scene depicting young star Damson Idris’ character, Franklin Saint, quite literally sweating out a crisis.

“This is the scene that moves us,” says Younger, as cinematographer Eliot Rockett unzips the tent flap that keeps video village dark, and exits to walk the several yards to the Mercury where Franklin sits at the wheel. Completing this scene will trigger the company move that Younger cites, but there’s plenty of business to handle first. Most crucially, as various anxiety-provoking elements swarm past Franklin’s field of vision, Rockett and his team will do a push-in from curbside into the car’s interior.

“The notion of the scene, as scripted,” Rockett explains, is that Franklin, who has just committed a plot-galvanizing killing, “is having to cover his tracks, and now he’s stuck in traffic by school kids piling out of a bus. He’s worried about the cops coming down on him and his crew — everything going south — and now he’s having a bit of a nervous breakdown.

The third season of Snowfall kicked off in July to positive reviews, much as the previous seasons had, and as it continues to weave together its overlapping plot lines — with the help of celebrated African-American novelist Walter Mosley, who’s joined the creative team — it’s steered a path to even darker and bloodier shocks and twists than those earlier narratives had supplied. Co-created by the late and much-mourned director John Singleton, the series has soldiered on with co-creator Dave Andron, who’s adding steady time on set to his ongoing supervision of the writers’ room. The relation of this work to Singleton’s 1988 landmark film Boyz n the Hood could not be more evident, nor more deeply cherished by this crew.

“There are a lot of people here [on set] who have lived through these eras, who can speak to the authenticity of the story, and we dramatize that. What John Singleton was so good at doing was taking that reality and knowing how to craft incredible moments within it [that could] really make you care.”

— Tommy Maddox-Upshaw

The loss still reverberates. At the conclusion of Season 3’s first episode, an onscreen card reading “For John” led off the credit roll. On the set today, the A-camera slate reads, in neatly markered words, “In memory of John Singleton.” For this strikingly diverse crew — many of them handpicked by Singleton — it’s the sincerest of tributes.

The saga of Franklin Saint began in the summer of 1983, in the heart of South-Central Los Angeles on bungalow-lined streets that were, via Franklin’s ascent as a crack kingpin, about to get a whole lot meaner. Fortunate in its casting of young British actor Idris — “I think he’s definitely a movie star,” Younger says — the show pursues three interwoven story tracks. Franklin begins as a self-aware 19-year-old who’s good to his mom (and loathes his absent, alcoholic dad), but stumbles into slinging some cocaine. He discovers how to cook coke into crack a couple steps ahead of the cartels who supply product to eccentric local drugs-and-weapons dealer Avi Drexler (Alon Aboutboul) — and also before canny CIA operative Teddy McDonald (Carter Hudson), who wants to churn up funds from any source he can to underwrite the Contras in their war with Nicaragua’s Sandinista regime.

Aunt Louie (Angela Lewis) and Leon Simmons (Isaiah John).

Prior to the capture of Idris’ tension-steeped car-interior sequence, Rockett had established the street geography with a shot looking east up Avenue 26 from a 20' crane. On the crane, the cinematographer explains, was a Sony Venice camera mounted to a DJI Ronin 2 gimbal, which acts as a remote head. “That shot allows you to then go in and play the character’s point of view, with the audience understanding the geography of the setting,” Rockett notes. “It’s kind of an unconventional sequence. He’s just sitting there, looking at these little bits and pieces all around him, without anything else going on — and we need to make the audience understand the stress that’s building inside of him.”

First AD Alex Leimone has been at work with the crew staging said bits, which will ultimately include: a school bus that stops and disgorges a passel of kids who cross the street, halting Franklin’s car; a father and daughter collecting a treat from a tinkling ice-cream truck whose sign says ‘Hoodsicles’; a lawnmower growling across the lawn of the picturesque, if faded, Lincoln Heights Branch Library (built via the largesse of Andrew Carnegie in 1916); and a carpenter with a screeching buzz-saw severing a chunk of 2x4 10 yards away.

To sell the scripted heat wave on this breezy 70-degree day, the costume department has been given the call-sheet note, “People are sweaty” — and Younger gestures toward the props department’s outsize gas burner blowing out fierce blue flames. “That’s to get that heat-wave shimmer,” he says. “Often you’d do that in post, but we’re doing it in camera.”

He and Rockett plot the push-in, eyeballing the path the shot will take from curb to car interior, as key grip Bobby Thomas deploys two crewmembers who set to work laying dolly track. “That was my old job,” Younger says, admiring their rapid work with pine and plywood. “Dolly grip. That’s as old as movies themselves — just shims, blocks and a level, like any contractor would use.”

Rockett re-enters the tent, checking his custom array of devices and readouts, most crucially the feed from this season’s go-to Sony Venice system. “I take an SDI feed out through Blackmagic [Design] Mini Recorders and into my computer’s Thunderbolt port, so that I can keep an eye on waveform monitors and take still images for reference,” the cinematographer notes. “That way, if I need to go back and match anything, I can take a quick look at the still I took of the scene and quickly match to it. I use a simple program called ScopeBox for that.”

Rockett, who has shot all but one of Season 3’s odd-numbered episodes, and Tommy Maddox-Upshaw, who has done the even numbers — and who will feature in the latter section of this piece — swear by the Venice’s dynamic range, especially its low-light capabilities.

Rockett notes that he hasn’t shot on film “for a number of years. I was on Grimm [from 2011 to 2016] when the substantial transition from film to digital really happened.”

To prevent reflections from the bright mid afternoon sun that would show on the car windows, Rockett has a polarizing filter placed on the Zeiss Super Speed lens. “I shot my episodes almost exclusively on Zeiss Super Speeds,” he reports. The cinematographer adds that he eschewed zoom lenses for his work with the Venice camera.

The establishing wide shot of the passenger side of the Mercury is captured with a static camera. Next, the Venice — mounted to a Chapman Hustler IV dolly equipped with an 8 Ball camera slider — is smoothly pushed toward the car, to its front window.

With the camera “on a 2-foot offset on the dolly, in order to push through the window,” Rockett explains, the production then makes use of the Venice’s tethering system. “They call it the Rialto,” Rockett says — after a famed marketplace in the Italian city from which the camera itself gets its moniker. When employing the Rialto rig, “the sensor block comes off of the camera,” the cinematographer explains, “and you run a cable back to the recorder. Basically, it creates a camera that’s very, very small.”

For the close-up of Franklin in the driver’s seat, Rockett will take advantage of another solution for tight spots. “Sometimes instead of the Rialto we’ll use a Blackmagic [Design] Pocket Cinema Camera 4K, as we’re doing here,” he notes, “because it’s a little bit smaller [than the Rialto solution], and it can be prepped more quickly.” The Pocket Cinema Camera is fitted with a Panasonic 7-14mm zoom.

Both Rockett and Maddox-Upshaw are quick to point out how important colorist Pankaj Bajpai at Technicolor has been to their individual and shared efforts. Having created a series of LUTs to define the color palette of the series for the previous two years, Bajpai — who will also perform the final grade — built up a new set of parameters for the third season. As Maddox-Upshaw will later note, “Because of the switch [to the new] camera system and the dynamic range of the Venice, he reconstructed the .CUBE LUTs from previous seasons — plus he added three more, per my request, because the storylines were going to twist into one another unlike before, so visually it should shift. They’re loaded into the camera right now, and the Blackmagic footage works remarkably alongside the Venice. You can drop it in here and there, and — now that I’ve seen it in several episodes — very successfully.”

Rockett adds, “Because the BMPCC 4K is able to acquire in a raw format, it’s then able to be corrected to match the Venice.”

By now Rockett is clearly deeply engaged with his monitor, and when the shot is accomplished, he seems a bit relieved it’s done.

With the essential footage of Franklin in the can, Younger oversees a sequence of cues — the lawnmower, the kids dawdling across the hot pavement, the buzz saw, and the father and daughter, who, Younger notices, don’t look quite right in their amble down the sidewalk. Even as the walkie-talkies chirp that the cops are pushing to lift the road closure, Younger says to Leimone, “One more, if I can have it?” And with that last take executed, he makes an assertion that seems all the more earnest because it’s a mere mutter: “Freaking great.”

What’s billed as “INT. TACO JOINT” — Episode 9’s Scene 32 — calls for a brisk company move to a nearby corner on Broadway. It’s a comfortably gritty practical location, where Rockett will skip lunch in order to consult with gaffer Justin Dickson and crew amid the cramped café’s oft-repainted wooden stools and tables.

It’s a typically clandestine setting for Franklin (who’s lived through several story-points’ worth of further threats and problems since the car scene that wrapped an hour ago). He’s meeting with Teddy — in the person of Hudson, who has just arrived on set — whose obscure government ties have gone from mysterious to alarming. Between carts, cameras, lights and crew, it’s a tight fit, but “there’s pretty good ambient light in here,” Rockett remarks. “I’ve turned off the fluorescent fixtures on the patio and I’m just establishing a bit of directional feel with an HMI coming from the off-camera side — we’ll flip it as we change angles, to get a little contrast on their faces in the singles.”

Such considerations count heavily for this scene, in which the two characters trapped in a deadly conspiracy realize they’re not only dependent on the other to survive, but they are, in the words of Andron’s script, “hit with the realization that despite everything … they’re exactly the same.”

Asked, as he watches, if the simmering face-to-face is a purposeful recall of a famous and similar confrontation between Robert De Niro and Al Pacino in Heat, Andron acknowledges it’s so. In fact, he says, Younger had expressed that he would happily embrace the Michael Mann classic as a visual touchstone, and the two had thus advised Rockett. Andron further notes that Franklin and the manipulative Teddy “have been enemies, going through things separately on parallel tracks, and now they’re colliding. Franklin’s at his breaking point.”

“Look at Eliot [Rockett]. This is so gangster. Can Deakins do this?

He’s doing his gig and also having a plate of tacos.”

— director Ben Younger

Rockett frames Idris on the right and Hudson on the left in a profile two-shot. As Idris angrily pounds the table, 1st AC Prentice Sinclair Smith racks focus on a startled woman, who can be seen in the space beyond and between the two actors. The dismissive look Teddy gives her, says Younger, is in part a recall of Tom Sizemore’s stony glare during a similar moment in Heat.

As crewmembers adjust the lights, Rockett works on a platter of the restaurant’s best efforts with one hand while tweaking settings with the other — which elicits a smile from Younger. “Look at Eliot,” the director says. “This is so gangster. Can Deakins do this? He’s doing his gig and also having a plate of tacos.”

Rockett suppresses a grin — as any comparison to master image-maker Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC is high praise — but between the labored coverage-reverses and the intensity of the confrontation, we’re in the midst of a delicate piece of filmmaking. Sirens in the distance insist on being part of the sound mix, and the buses on Broadway groan noisily past as the fans shift hot air during a momentary silence. “If this stuff was easy,” says Andron — clearly loving how, despite it all, the scene is playing — “everybody would do it.”

It’s Day 2 of our visit, and we’re observing a sequence that takes place 12 days after Franklin’s trying times in Lincoln Heights. We’re in the projects of Pacoima, where a real-life crack-fueled gang war was waged in the ’80s, though tensions have since eased. Crew parking is amid territory once despotized by gang rule. The location is standing in for old-school South-Central, the setting of today’s shoot.

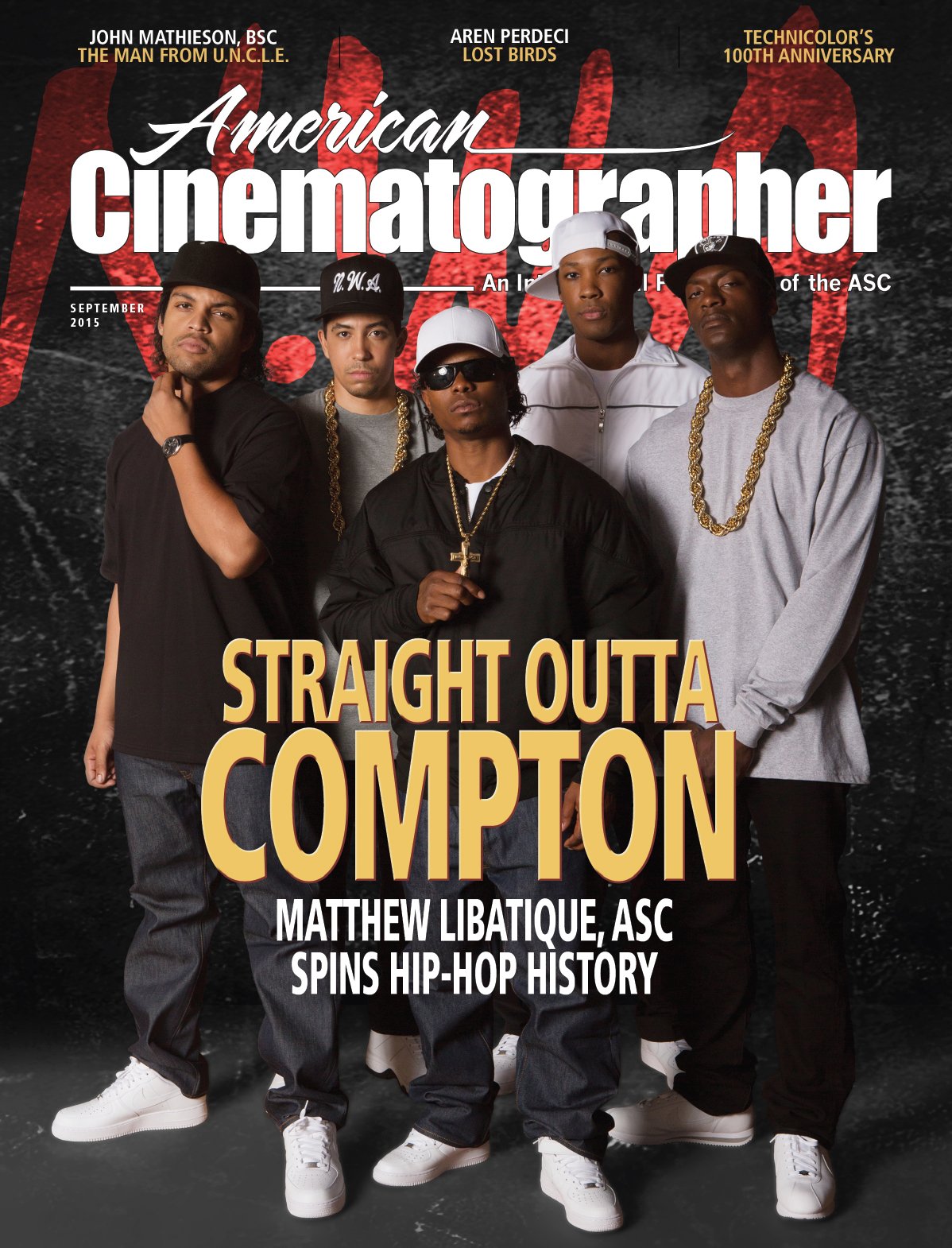

Director of photography Tommy Maddox-Upshaw, whose credits include shooting 2nd-unit on the 2015 hit Straight Outta Compton [AC, Sep. '15] about the rise of the rap group N.W.A., presides over the camera crew. “My gaze is a little more personal,” he says. “Being a kid who grew up in the ’80s and ’90s in Mattapan, the inner city of Boston, during the crack era, I saw a lot of these same things happen, the drugs and violence in my neighborhood and in my own family.”

With the season’s shooting schedule rushing to a close, such deeper considerations must couple with knocking off script pages. “It’s super-aggressive,” the cinematographer says. “We just want to be sure that we finish out the season strong. We’ve got 22 locations in eight days.” For the selection of the Sony Venice, Singleton — Maddox-Upshaw’s friend and neighbor in South L.A. — “left it up to us. I brought up to Eliot that I’d already worked with it before, and it’s such an easy and dynamic camera in the post workflow.”

He reports that the Venice offers an impressive ability to create the desired image in-camera. “We have this dark-skinned black man and we use so much natural light,” he says, “and on exteriors, to see Damson’s face hold that type of skin tone so well in the foreground against hard-sun backlighting, without letting the blue sky and cloud details blow out, is a testament to the camera itself. This is a game changer.”

Threading through the meticulously art-directed project’s crabgrassy yard strewn with broken bikes and makeshift picnic setups, comes Episode 10 director Sunu Gonera, who was raised in a township in Zimbabwe, and nominated — not long after moving to the U.S. — for an NAACP Image Award for Pride. The task he and Maddox-Upshaw will share is to convey, for these minutes that will play out very near the end of the season finale, the state of mind of a protagonist who’s in even worse straits than Episode 9 revealed: wounded and immobilized, in a nightmare state. Franklin is ostensibly in a bed, but his spirit is engaged in a psychic walkabout that we’re here today to observe. To show that state, Maddox-Upshaw notes, the production is creating footage of “an augmented reality.

“We’ve figured it out,” he continues. “It’s a little scary and kind of a bear, but I think I have a pretty good handle on what it is, and I think at this point the actors do as well — like, ‘Okay, this is the world where I am.’ It’s a different texture, not the same South L.A. that our narrative normally takes place in.”

As Franklin moves ghostlike through the scene that’s slugged as “LEON’S BARBECUE” — referring to Franklin’s best friend and henchman, played by Isaiah John — people “don’t necessarily eyeball him when he walks by, because he’s not the kingpin with bodyguards now,” Maddox-Upshaw explains. The cinematographer suggests that the production has gone a bit “theatrical” to create moods in the camera. “We’ve changed the lenses from the regular narrative, and even changed the LUTs,” he says. “So I’m taking creative license, with a lot of flaring.”

Indeed, throughout his episodes, Maddox-Upshaw has been pairing the Venice with modified Zeiss Super Speed “MXF” glass (see below), but for Franklin’s fever dream, the production has transitioned to Canon K-35s — “with the big circular flares,” the cinematographer notes — which are shooting wide at T1.4-T2. “I love the use of minimal depth of field.”

Steadicam operator Xavier Thompson follows Idris closely as the performer winds his way through the obliviously partying group at the barbecue. When a babe in arms drops a ball in Franklin’s path — and Idris, with good actor’s instincts, picks it up and hands it back — Xavier catches the move smoothly. Says Maddox-Upshaw, “Xavier came on this year and has learned so naturally — he just seamlessly went down, found the ball, and got with Damson. As his shot tells the story, you’re completely in Damson’s world. It’s wonderful when you can have a camera move that feels emotional like that.

“That sequence was half natural light, plus one 18K HMI backlighting the smoke and edging Leon, young John and Franklin as the sun was going down on one side of the project,” Maddox-Upshaw details, “yet the real sun was doing work in the foreground. It worked nicely. You can’t tell the difference, plus we got a nice flare.”

Regarding the additional cinematographer on Season 3 of Snowfall, Maddox-Upshaw adds, “Steven Finestone, who was A-cam operator, got to DP Episode 5. He was an amazing operator, who was an amazing collaborator and mentor to the younger Xavier Thompson, [who operated] Steadicam and B camera.”

Familiar with the project-apartments’ cramped rooms, such as the one being employed for the next scene, the crew stuffs in gear and bodies like it’s a circus trick. Maddox-Upshaw sizes up the light — late sun suffusing through lipstick-red strips of translucent tinting on the windows. He monitors some discreet peeling-back of the tint — “a perfectly placed leak,” he says at one point — to get just enough light for his Convergent Design Odyssey7Q+ rig, his “favorite tool for the Venice,” to read out that he’s within usable parameters. “I can actually [shoot in very] low light — .25 footcandles [at 2,500 ISO] with brown skin tones — and have no noise,” he says. “I was often that low in light level, and [I could] see the Odyssey 7Q read that there is still detail at sub-10 IRE.

“I don’t use a waveform,” he adds. “I use the Odyssey with its false color and spot metering application. Regular waveforms, and even light meters, don’t work with enough accuracy with this camera because of how far down the camera can actually go. I set my own exposure table with the Odyssey because of how sensitive the camera is, and how I like to push the limits of it.

“Tomas [Voth], the production designer, is awesome about leaving opportunities for light to fight through textures on windows or walls,” the cinematographer continues. “So we broke apart the [red plastic tinting on the windows] and backlit them with PAR cans and [Tungsten PARs] for that scene, making use of tungsten during the day as backlight.” Introduced to the production by Season 2 gaffer Phil Walker, the Tungsten PAR incandescent fixtures “are fantastic because they can [appear as] sodium vapor, metal halide or tungsten, and they don’t use that much power,” Maddox-Upshaw enthuses.

Franklin’s still in his dream state, and his very bad day does not improve in the claustrophobic den where five strangers regard him coldly. “Leon rolling with this crew, who don’t look like they’re to be messed with, we’ve never seen before,” the cinematographer says. “A totally different universe.” After Leon squabbles with his girlfriend, Wanda (Gail Bean), the crew moves on and Thompson hoists the Steadicam once more.

There’s a mood shift that accompanies the next shift in setting. The actors are back on the yard, embarking on a quickly blocked, half-improvised, naturally lit conflict, as a young filmmaker — a frank and loving homage to the era-defining Singleton — runs afoul of Leon by documenting the goings-on with his vintage Minolta 8mm camera.

This scene was shot with “natural light, for the most part, and one 18K HMI with 1⁄2 CTS backlighting half of the backyard, and raw sun doing the rest,” Maddox-Upshaw later explains. “We had some smoke in the air for the sun to accent. There was no diffusion and no bounce-return on the lights.”

For Thomas, it’s a quietly emotional moment, as the key grip and Singleton were roommates back in 1987 when both attended USC. Though neither had predicted that Singleton “was going to in some ways overturn cinema,” Thomas recalls, “I got the opportunity to read Boyz n the Hood as he wrote it. I told him, ‘Great script, but no way they’re going to let you take those expensive cameras in the ’hood.’ It was so exotic to people, nobody had really dared to enter that world.” Nonetheless, Singleton even went on to insist to the studio that he also direct it. The friendship held as Thomas and Singleton’s careers diverged, but for Snowfall they reconnected. “He let me read the script, and I said, ‘This is fantastic — this story needs to be told.’”

As Leon continues hollering and flailing at the teenager, who gives ground but defiantly keeps his camera rolling, Franklin dazedly intercedes. Leon sulks. As life imitates art, both the production and the young filmmaker capture their concluding footage. Windblown dust from the scuffle breezes away, and an unspoken sense of a tribute well made ripples across the set.