Lachman, Haynes Reteam on The Velvet Underground

In this doc, the longtime collaborators revisit the seminal band that inspired them both — an examination of the longterm influence of innovative music on popular culture.

Interview by Mark Dillon and Stephen Pizzello

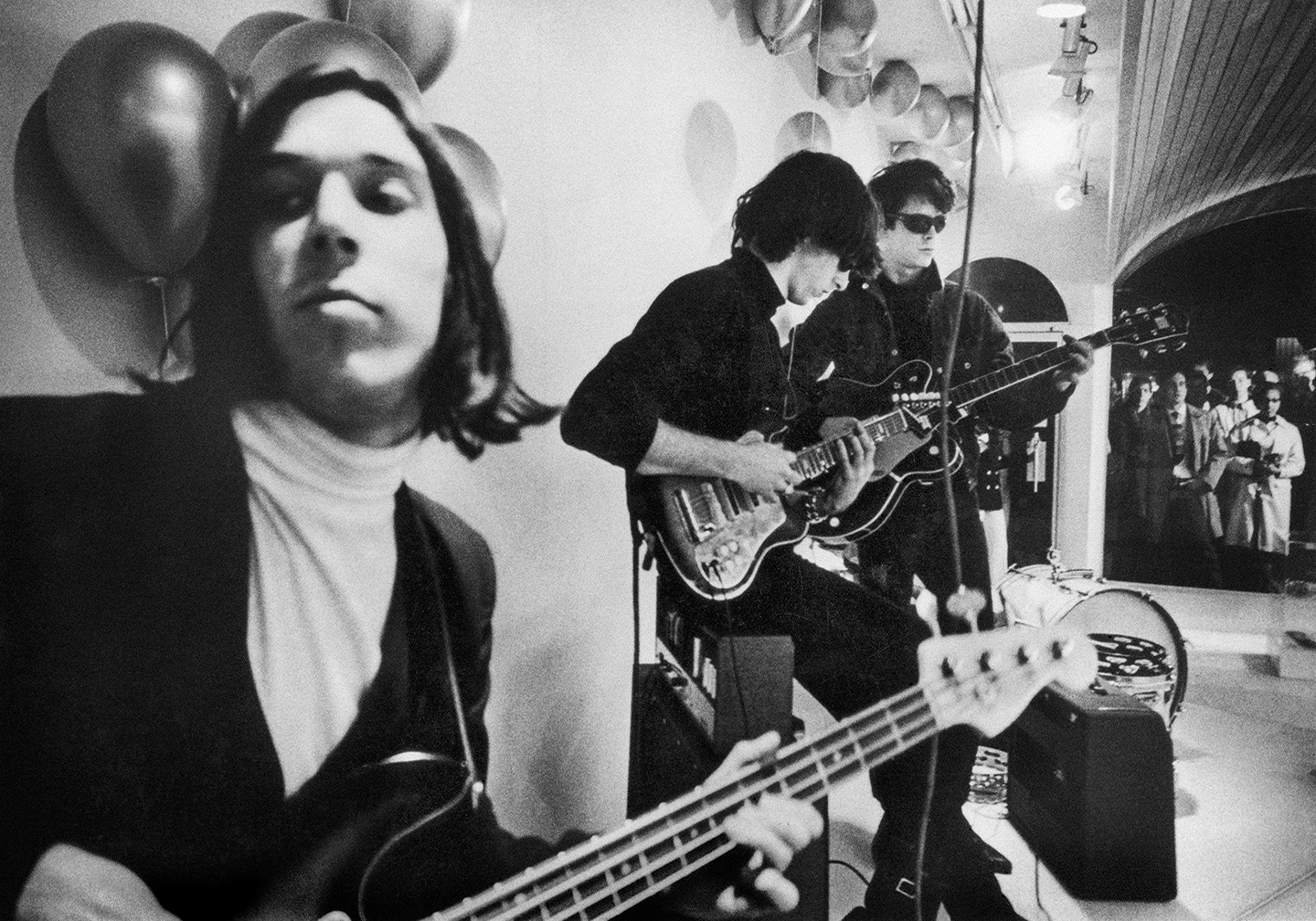

The Velvet Underground images courtesy of Apple. Wonderstruck image courtesy of Amazon Studios.

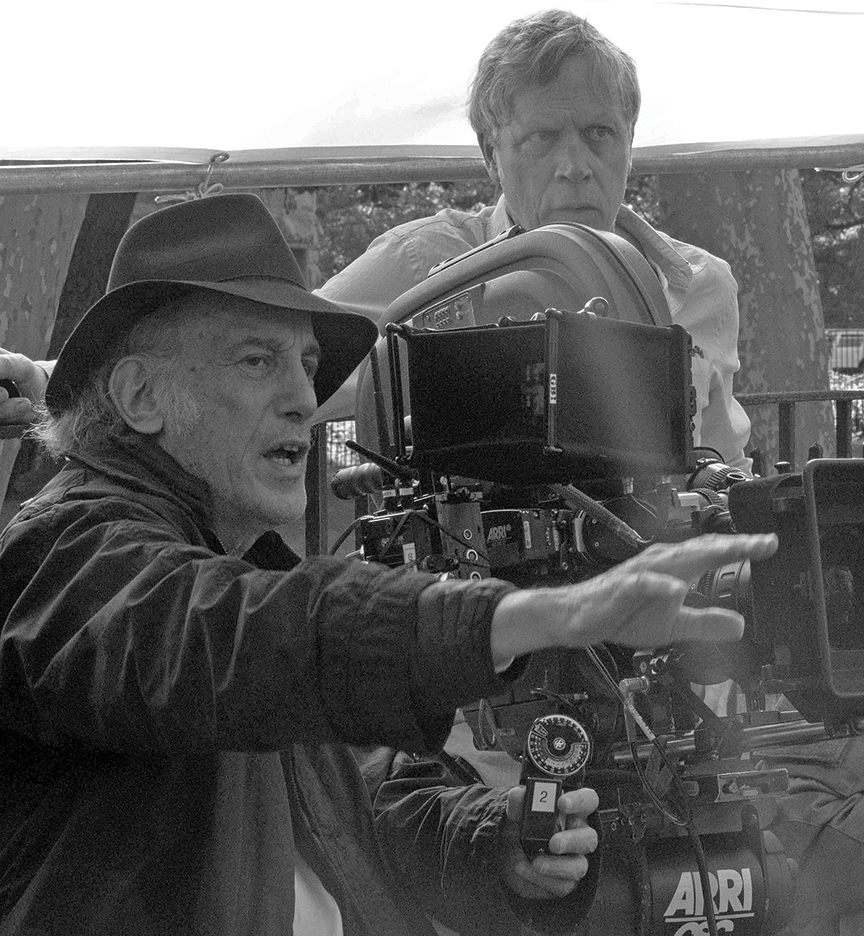

Director Todd Haynes and ASC member Ed Lachman’s work together on The Velvet Underground — an exploration of the seminal rock band founded by Lou Reed and John Cale — represents the longtime creative partners’ first documentary collaboration. Haynes and Lachman have paired on seven features (Far From Heaven, I’m Not There, Carol, Wonderstruck, Dark Waters, and the forthcoming Fever, a biopic about singer Peggy Lee) and two television productions (the miniseries Mildred Pierce and a segment of HBO’s Six by Sondheim).

Taking cues from the avant-garde cinema of Velvet Underground confidante and promoter Andy Warhol, as well as the work of other independent filmmakers of the time, the documentary combines new and vintage interviews with a panoply of archival footage. The result is an immersive approximation of the kind of multi-media “experience” the band presented in its live concerts at Warhol’s Factory and other venues. The film features split screens and multiple panels to convey the ambience of the eras in which the Velvets came together and produced their brand of highly experimental music, influencing countless rock acts that followed.

Haynes and Lachman spoke with AC to discuss the project, which is now streaming on Apple TV Plus.

American Cinematographer: You two have had a fruitful collaboration over the years. Why do you think you’ve clicked so well?

Todd Haynes: When we were just meeting each other and having the first talk about Far From Heaven (2002), Ed brought bags of art books, and I would later see that’s how he lives. He surrounds himself with references from artists, photographers and books about film. We immediately began to talk about the project from the vantage point of artmaking. We all are involved in this medium and in various kinds of art and craft and narrative storytelling, but you don’t always feel like the artistic sensibility is driving the personality of everyone you work with. [It does] for Ed and me, though — each project has offered a collaborative dive into the language and references, and we both get off on that.

How about you, Ed?

Edward Lachman, ASC: Todd had a similar background. I studied art history and film, and he studied art and semiotics, so we already had the same grammar to talk about things. He was inspirational about his references. He always goes further than looking at a film in terms of, ‘Oh, that’s the style we should represent.’ He always understood why the style was that way and how it was created. Each film takes us on another journey, and the process always inspires me.

Do your shared sensibilities extend into music?

Lachman: Bob Dylan was always influential for me growing up, so [I’m Not There, 2007] was a film I really wanted to be involved in with Todd. Back in the early ’70s, I had done a promo video for Lou Reed [for the 1973 Berlin album]. Lou came up and kicked the tripod out from under me. I was in shock, grabbing onto the camera as he told me, ‘Do it like Andy [Warhol]!’

Later, I directed a performance film of the album Songs for Drella [1990] for Lou and John Cale — an homage and memorial to Andy three years after he died. During that shoot I mentioned the tripod incident to Lou and he said, ‘Oh, I don’t remember much from back then.’

Haynes: Ed has had his hand in every phase of filmmaking, touching back to European art cinema from the ’60s when he was coming of age. He’s studied under great filmmakers and artists and DoPs from that period, so when we discuss the great American era of independent film, [Ed often has] a direct link to people we’re talking about.

Were Ed’s firsthand experiences helpful to you?

Haynes: I always felt an easy atmosphere because Ed had a history with so many of the people who were there. It made them feel comfortable. It would have been interesting if Lou Reed was around [he died in 2013], but I know that Ed being the DoP put John Cale at ease.

“Each film takes us on another journey, and the process always inspires me.”

What was the initial spark for this project?

Haynes: [Reed’s widow] Laurie Anderson decided to make his archives available to the New York Public Library, and Universal Music Group — which controls the masters of Verve Records [the Velvets’ first label] — asked her if this would also be time for a documentary on the band, which had never been done conclusively. Shortly thereafter Laurie and I met, and then we were contacted by [UMG head of film and TV production] David Blackman about doing this.

I knew there wasn’t traditional material featuring the band, and Lou Reed is not with us and [vocalist] Nico is gone [she died in 1988], so the project would come with inherent challenges.

But that’s why you do things, too.

The film is presented largely in split screen with shots from avant-garde 1960s movies next to talking-head interviews, allowing the viewer to marinate in the art scene that helped give rise to The Velvet Underground. Did you want to make the documentary ‘like Andy’?

Haynes: We had an amazing opportunity to include the entirety of the avant-garde filmmaking culture that was so prolific and robust at that time. Jonas Mekas was really the central force — he always had a venue for showing filmmakers from New York and beyond, from older experimental cinema to the newest thing Warhol rolled out of his camera through the 1960s. These were gathering places for all these artists we’re talking about in visual art, music, performance and poetry.

I was thinking we were going to be predominantly referring to the 1.33:1 16mm aspect ratio [with the archival footage], so what do we do with that? How do we multiply or divide up our frame? We [decided to reframe] our interviews into 1.33 so mostly it’s the two 1.33 portraits or the portrait next to other information within the 1.85:1 [release ratio]. That is the format of Warhol’s Chelsea Girls, where it was two 1.33 projectors side-by-side through the whole film. We not only reflected the integrity of 1.33, but also did things only a Warhol-brain would spot.

“How do we multiply or divide up our frame?”

You shot interviews with the likes of John Cale, Velvet Underground drummer Moe Tucker and Martha Morrison, the widow of guitarist Sterling Morrison. How did you approach shooting those?

Lachman: It was interesting how Todd married contemporary interviews with the archival footage. I came to think of the interviews like Andy’s photographic silk screens, with colored flat panels behind each subject, and Andy’s black-and-white screen tests.

Haynes: We would pick different colors based on the color swatches from Warhol’s silk screens. They have a kind of dirty pastel palette to them. Then we’d put some texture on them like they were painted walls in tenement apartments. When we were shooting at someone’s apartment, like Jonas’, we’d bring [the panels] in. Otherwise, we were in a little studio and the artists would come in and do them there.

Lachman: My other reference was Andy’s Screen Tests series, so it’s a one-light source. They’ve been lit rougher than I normally would, but I tried to maintain that quality of somewhere between the Screen Tests and his lithos. We were shooting digitally, but at the end of every interview we would shoot some Super 8 on a Beaulieu Pro camera. It wasn’t sync sound, so we would use that just for image. I thought that married the present and past very well.

What camera were you using predominantly?

Lachman: My Arri Alexa Mini, shooting in 2.8K ArriRaw. We even did that on [the 2019 feature] Dark Waters. I tried to keep it as low-res as possible. I’m always opposing ‘digital look,’ so I also used an older Angénieux 25-250mm HR 3.5 zoom lens. Then we also applied some LiveGrain, which Todd and I are big advocates of using — again, to marry the film with the digital. We didn’t mind the quality of some of the older [video] archival footage, because that has its own look. If I could have shot to make it look like back then, I would have.

Ed, do you have a particular tool set to make interview subjects comfortable and get a better response out of them?

Lachman: I like to be a little longer with the lens so I’m not right on top of them. And I have the lighting set beforehand, so when they walk in, I’m not fiddling around. And just let it go — Todd did long interviews, which also puts them at ease. The great thing about digital is you don’t have to worry about changing film rolls. So that gives fluidity to the discussion, and you can talk about other things while the camera’s still rolling. I try to keep the lighting as low as possible, so the filmmaking process isn’t interfering with why we’re there: to get them to share their story. Like Todd said, sometimes we were in people’s apartments, so I would use a 1K or 2K in a book light.

How would you describe the interplay between the two of you on set?

Lachman: We’re each in our own worlds. Once we’re there, we do what we do.

Haynes: Ed would be reframing while we shot. This had a more improvisational element, because [we were doing] long, static shots and Ed would widen and narrow the frame. He knew we were going to manipulate the size later to 1.33, but we still wanted to give variation in size. And those choices being made intuitively by Ed always seemed to work.

Lachman: It’s important I hear what’s being said. I have a headset on, so I’m in the moment. On other projects, sometimes I like to move the zoom slightly in to reflect emotion, but here we were working with static frames, so I could do the same thing with frame size.

What was your approach to the finishing at Harbor Picture Company?

Haynes: It was about not imposing a strong language over the material, not oversaturating or adding too much contrast to the footage, so you really could see the blacks. I wanted to keep the mistakes and imperfections of the transferred sources — which were sometimes from negative and sometimes from interpositive — and not clean up the edges, which were often ragged.

Ed, you’ve recently been in a color suite doing new work on the Songs for Drella film. Will we see that sometime soon? It’s an ideal companion piece, as it features Reed and Cale reuniting to perform their tribute to Warhol.

Lachman: It’s been screened at Telluride, and by the time this article comes out, it will have been shown at the New York Film Festival. We’ll also be showing at festivals in Europe.

You shot that without the audience present, right?

Lachman: Lou didn’t want cameras between them and the audience, so I suggested shooting the rehearsals as if they were in a performance. That allowed the intimacy of getting close to them and not worrying about an audience. I could set up dolly tracks. So I did that for two rehearsals, and we also shot two performances in one night with multiple cameras, but I never shot the audience. It became about the intimacy between the two of them — a confessional between Lou and John.