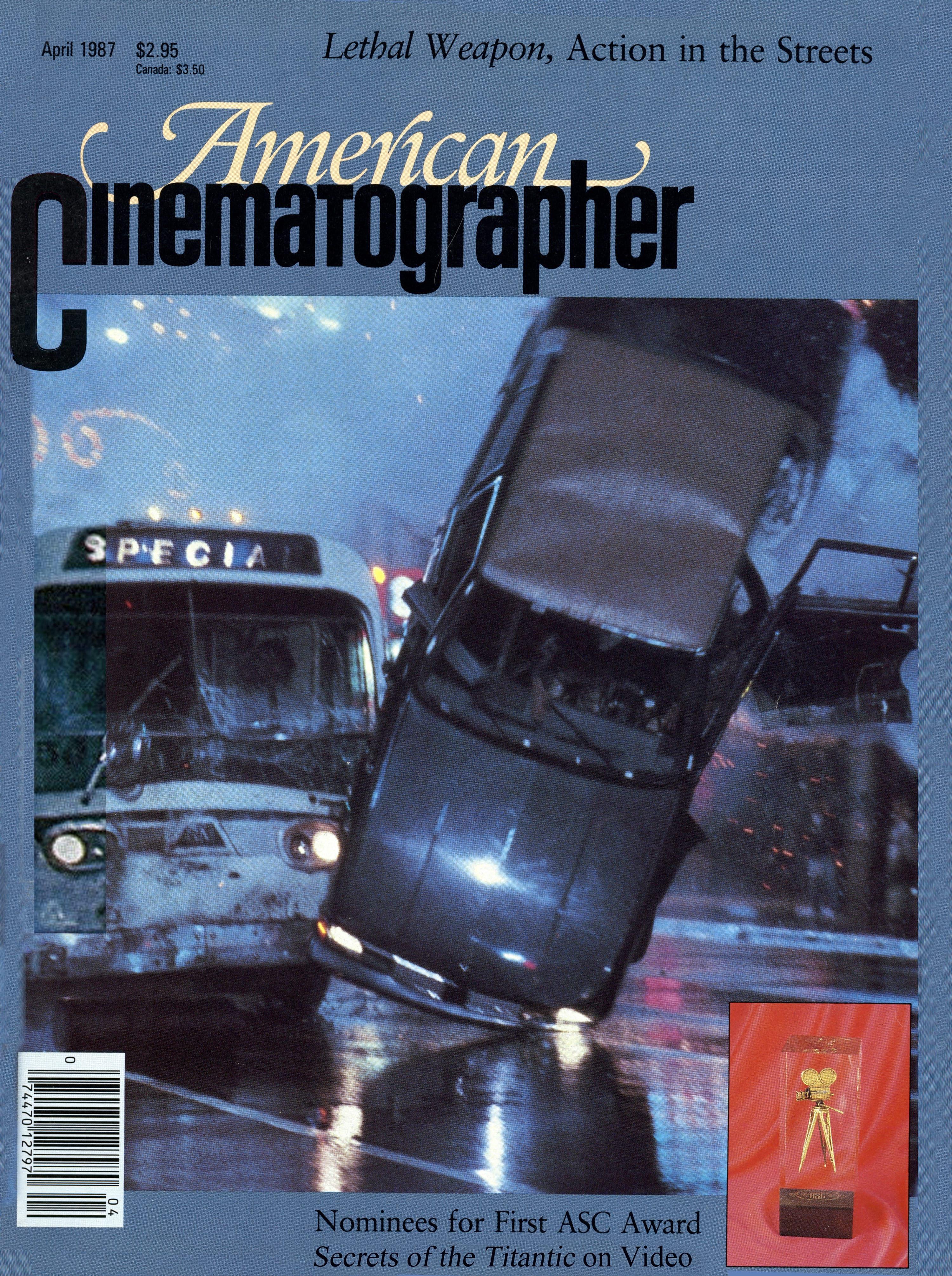

Lethal Weapon: New Look for Old Theme

Cinematographer Stephen Goldblatt teams with director Richard Donner for an action-packed crime picture set against Christmas time in Los Angeles.

Article by Bess Wiley

Unit photography by John R. Shannon

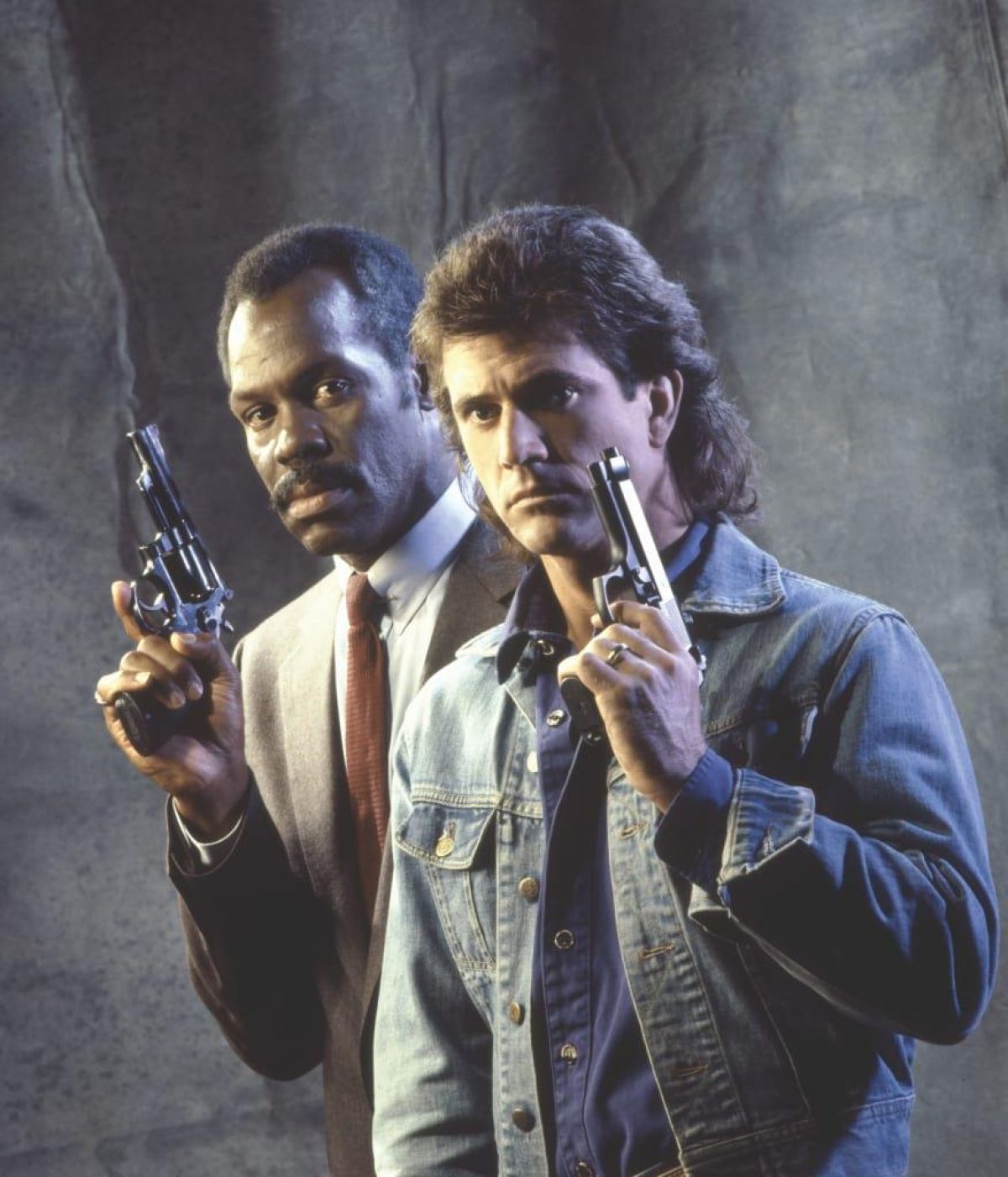

Lethal Weapon is the story of Riggs and Murtaugh, two L.A. cops who both fought in Vietnam. They hate to work with partners. They have nothing in common and they have been assigned to work together. Riggs (Mel Gibson) has recently lost his wife. He’s a man with a death wish. Murtaugh (Danny Glover) is a devoted family man with a solid reputation. As they investigate a suicide which turns out to be murder, they realize that they are dealing with trained mercenaries running a lucrative drug smuggling network with roots in a covert war in Vietnam.

Lethal Weapon, according to director Richard Donner, “is about a man who goes through a major life change over honor and his relationship with his partner. The arena is the LAPD investigating a murder, yet it is about the developing relationship of two cops. We are trying to produce good entertainment, packed with a lot of action and from that develop an interesting rapport — a sense of humor between two people.”

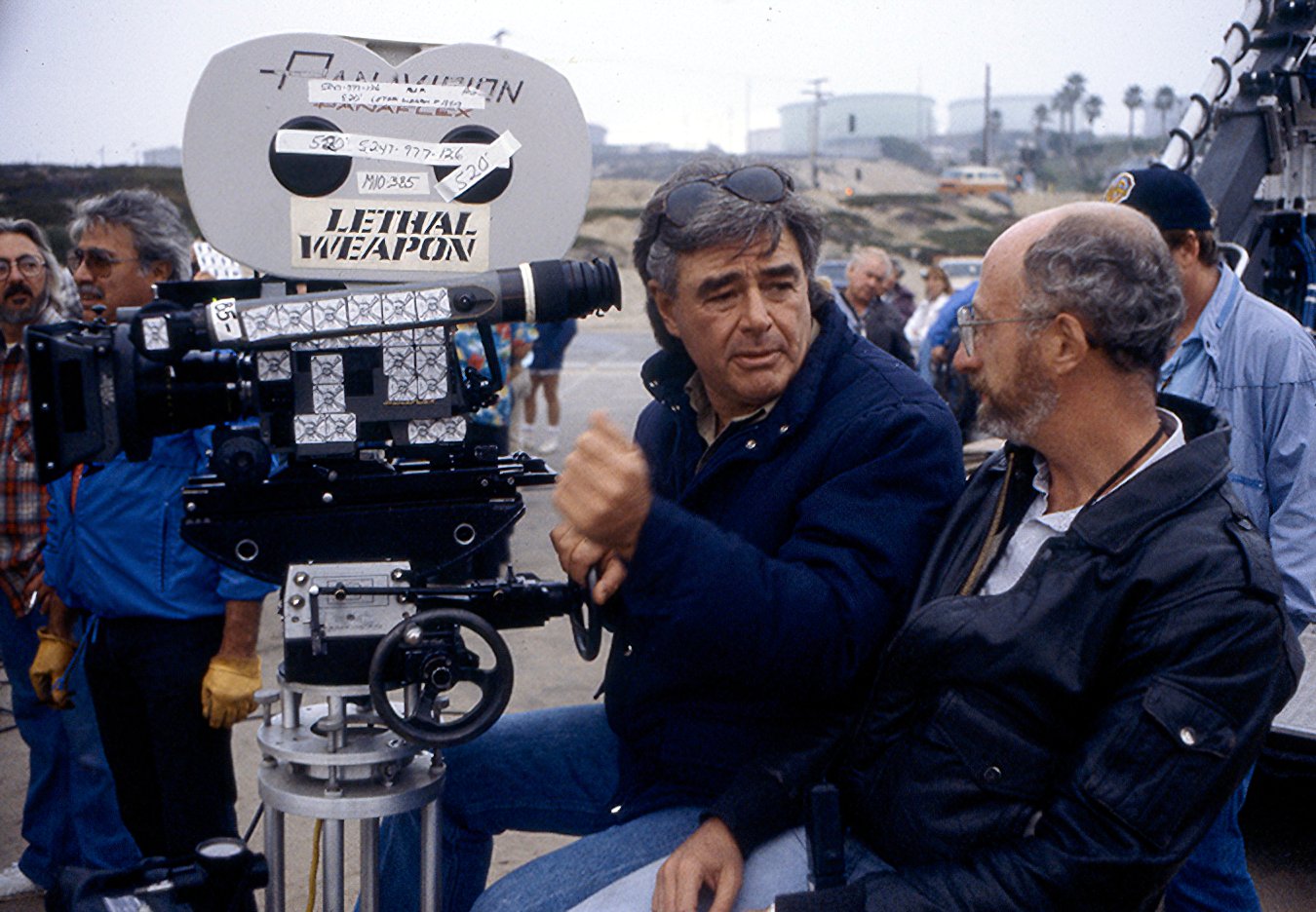

Director of photography, Stephen Goldblatt, says of his collaboration with Donner, “One of our favorite mutual films is Point Blank and this is an attempt to work in that style. Yet what is interesting for me and what is interesting for the audience is the story. I am telling a story with the camera, Dick is telling a story with his actors, the actors are doing it with performance but it is the story that has got to go ahead. As an Englishman, I thought this would be a wonderful opportunity to do an action film in my new home town, Los Angeles. It had its own problems - doing major action sequences at night is tough on everyone. But you learn. Every day that you work you learn.”

Although both Donner and Goldblatt view Lethal Weapon as their first ‘action movie,’ the team-up brings together a tremendous variety of experience. Donner’s previous efforts include The Omen, Superman, Inside Moves, Ladyhawke, and The Goonies. He was born and raised in New York and studied business and theater arts at New York University. Following work in bit parts, he gained an assistant directorship to Martin Ritt, and then became director of a number of plays during the heyday of live television in New York. He also made industrial films, commercials and documentaries.

Goldblatt grew up in England and became interested in cinematography concurrently with his career in still photography. He attended the Royal College of Art Film School. His work as a still photographer included being a stringer for Paris/Match as well as being a staff photographer for Apple Records. Work as a cameraman followed in industrials, commercials and documentaries. His features include Breaking Glass, Return of the Soldier, Outland, The Hunger, Young Sherlock Holmes and Cotton Club.

“One of the great arts of a cinematographer is to be able to NOT light, to specifically choose what you want to light and not light the rest of it so you get contrast, you get mood, you get atmosphere.”

— Stephen Goldblatt

Working closely with the director and the cinematographer was production designer J. Michael Riva, who won an Academy Award for Ordinary People, and an Oscar nomination for The Color Purple. Additional feature credits include Brubaker, The Goonies, and Buckaroo Banzai.

“There are,” says Donner, “about three or four people close and important to the ‘look’ of a picture. The input you get from the cameraman, the production designer and your editor (Stuart Baird), determine the style, the attitude and the size of a picture. It comes from them. I spend many nights in the trailer just rapping with Steve and the guys. We’d bring Shane Black, the writer, back in and rewrite then and there. Stephen provided an attitude that provoked something wonderful.”

The picture was shot in and around Los Angeles. Locations included Lake Mirage, Long Beach, Santa Monica, Inglewood, and West Hollywood. “This was not a stylized film, like The Hunger,” says Goldblatt, “where you were into a style outside of the story. At the rate this film progressed, there wasn’t much opportunity to hand pick locations. We didn’t see some of them until a few days before we shot them. For exteriors, you need to have more time to work the location than we did. For lit exteriors, now that’s a different story. With light, you can change the look of all sorts of stuff. I felt that I got a very definite look to it.”

Lighting the picture covered every combination of day, night interiors and exteriors with the more difficult action sequences shot at night. “Once I saw the locations, I had a pretty good idea of what I wanted. There aren’t many films you can’t handle with a basic package of say four arcs, and then work down from there. On certain scenes, we brought in extra equipment,” Goldblatt said.

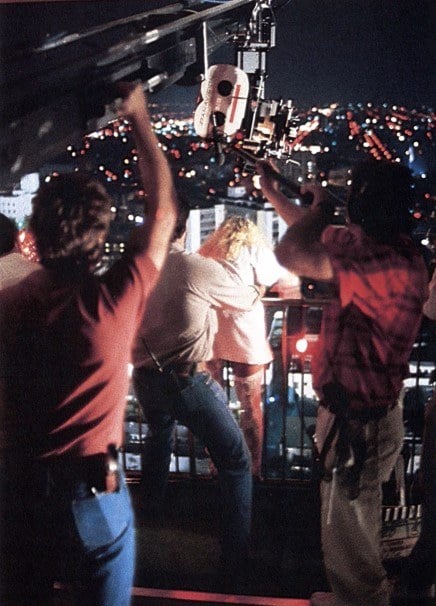

In the opening scene, Long Beach is viewed from the 30th floor of a young woman’s apartment as she walks out on the balcony after a drug binge, and leaps to her death. “In this sequence,” Goldblatt explains, “we start inside the room, over her shoulder and we go with her as she walks out through the doors onto the balcony. We literally had to light Long Beach, and so we used the Musco lights.” [Musco lights are powerful beams once used only for lighting football stadiums.] “The camera continues further out past her shoulder, dips down and gets her dizzying point of view 300 feet up. We used the Matthews Cam-Remote on a British arm, the Python, that Chapman has here, all on a dolly. To have rigged it any other way would’ve taken forever and would’ve been far more dangerous.”

As the woman leaps the 30 floors to her death, her view of Long Beach and the buildings around her were filmed with three Arri’s mounted on a rig that slid down the side of the building. (All the spectacular falling stunts and accompanying rigs were provided by Dar Robinson, who sadly met a tragic death on a feature immediately following Lethal Weapon.)

Continuing the opening shot, the next cut reveals the car towards which the woman is falling. This was shot at the studio backlot using the Cam-Remote on a Python high above an airbag. “Stretched over the airbag, is a canvas painting of the impact point on the street where the girl is dropping toward a car. You see a real human being falling toward it. The perspective of the painting is great. It matched perfectly the lighting of the original car in Long Beach. The camera then cuts to the car interior imploding from the impact,” Goldblatt explained.

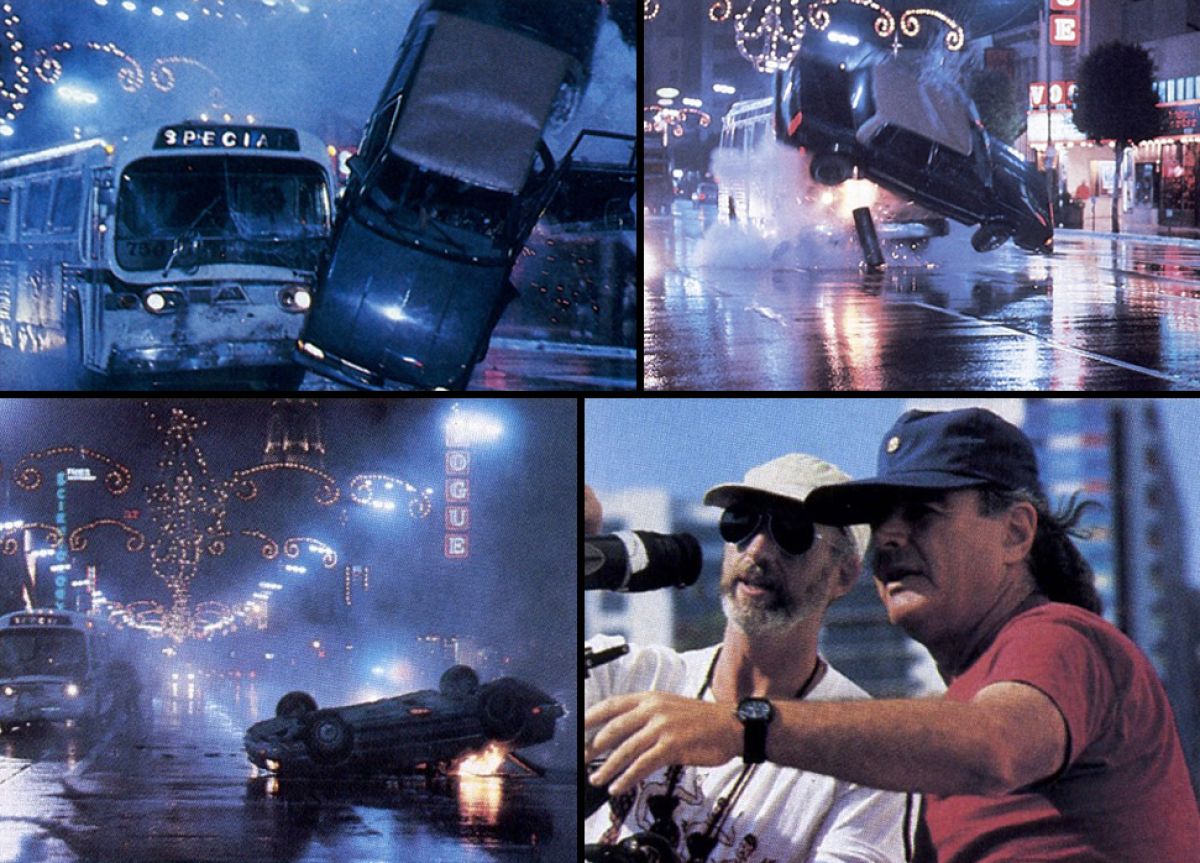

Another demanding sequence involves a bus crashing into an escaping drug dealer’s automobile. Goldblatt elaborates, “The worst thing to do on a great night location is to overlight it and quite often nowadays with [Eastman Kodak] 5294 you don’t need to light much — just kickers. On Hollywood Boulevard, blocked off for a half mile, you’re going to need a bit more light than usual. We asked the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce to string their Christmas lights early. We also used some arcs on Condor arms just to get kicks off the water in the street. I love to use water for the streets - it helps everything. It helps your exposure, it helps everything stand out. You really need a deep negative to get a meaty look. I had done tests of the street and we shot at T2.8. If we had shot at T2.3, we would’ve read the shadows — they would’ve been too light and it would’ve been awful. I also used smoke in this sequence after the heroin-loaded car explodes. We used cornstarch blown by Ritter fans. It was a mess but all this stuff going into the air helped me. I love to use smoke because I seldom use filters. I don’t like the look of filters. I like the smoke to do it, the light to do it, the water to do it, stuff in the atmosphere to do it. It looks better. I might use a very little bit of filtration on a woman, but generally I let the light, exposure and great make-up do it.”

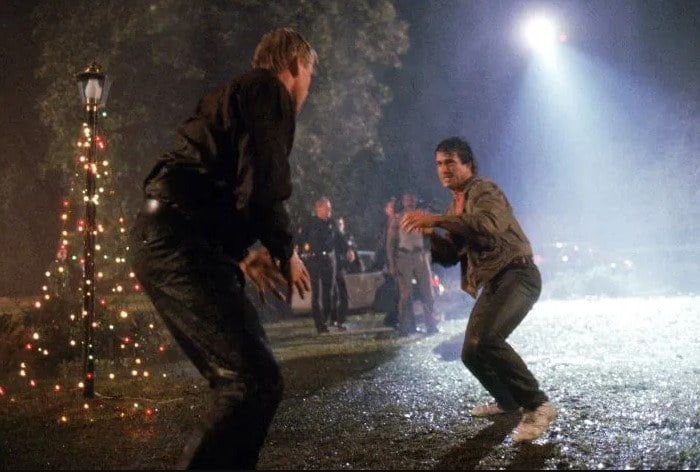

Perhaps the most unusual action sequence of the film is the climactic showdown between Mel Gibson and Gary Busey in a hand-to-hand martial-arts fight to the death. The filming was spread over four nights, shooting from dusk to dawn, resulting in an edited sequence that lasted only minutes on screen. Night after night, Gibson and Busey, in clothing drenched by water exploding from a burst fire hydrant and blown by Ritters (standing in for a police helicopter) performed the meticulously planned fight sequence in its entirety and also broken down into short cuts. “You simply cannot get a fight with any power in a few takes,” said Goldblatt. “You need a lot of material.

“If anything I always had that sequence in mind. It had to be climactic. But how do you turn a fight on a lawn into something else? With the use of the water. We HAD to have the water, even though we were all drenched. Without it, it would have been really dull. With the helicopter searchlight coming in as a source and the water, it really gave the scene some stature. I used 10Ks on this sequence more than anything. We used the helicopter and its light just a little bit, and then we mounted helicopter searchlights on a big throw-up crane just to simulate the effect of backlighting through the water.

“I like to use color and put tungsten lights on dimmers and use gels here and there to get depth. I don’t like to use blues on night exterior arcs. It’s the equivalent of ¼ blue on a tungsten source. That’s as blue as I like on a night exterior, so if I can get the stop, I would use a ¾ CTO on an arc. Or else if I were losing too much light, I would try to get the labs to correct. It gets blue very quickly. I used ½ CTO’s on Hollywood Boulevard, because the street lights there are that blue. It just matched in better,” Goldblatt said.

“I enjoy and am good at lighting in low light situations. I’d happily do a whole film like that. I light with my eye and then measure with my spot meter. If I’m worried I take a reading off the shadow side. If I remember right, when we exposed at T2.5, generally on interiors, facial highlights would be about T2.8, and the shadow T1.4, T1.3. The hot bits off the kicker were, of course much hotter. The most interesting thing for me is the range of colors and the contrast. I don’t like to overlight. I hate overall light. I hate to use a wash. If I use a wash, I still try to confine it. One of the ways to do it is in conjunction with the designer. If you do use a wash, have a dark room so that the faces pick up and the room drops down for contrast. I want things to look snappy, with a 3-D feel to them,” Goldblatt avows.

In reviewing some of the daylight sequences, Goldblatt stated: “The problem with day exteriors is the inherent contrast is so high with that high L.A. sunlight. This was not the sort of film where they would really wait for the light, so I had to do what I could with it. The main consideration in lighting these scenes was the high sun in L.A. with Danny Glover, a very black actor, and Mel Gibson, a very white actor. For day exteriors it’s tough to maintain the balance with these guys moving around. Quite often when we weren’t using the Shot-Maker (camera car), I was putting an arc on it and spotting it directly on Danny’s face and it doesn’t look lit. It was frightening using that amount of light. Of course, you’ve got to have an operator on the arc if they shift a little bit. If Mel got in, he’d white out!

“The thing is to have great action,” Goldblatt continued. “As an example, there is a scene where a hooker’s house explodes. This was a special effects shot covered with five cameras. We timed it because it is on a flight path to LAX. Just as a plane was crossing over the roof in the distance, we blew it up. It was good fun! And later on, there was nice back light with the smoke going through.”

One sequence in Lethal Weapon has Gibson trying to prevent a man from leaping to his death from a twelve story building. He tricks the man into handcuffs and leaps with him off the building into an airbag set-up below. “I suggested this building to do the sequence as I had photographed it as a still before and I love it. It’s so L.A.! ...The white of the building and the blue of the sky. Here the contrast was two white guys on top of a white building. They got filled in, it was easy,” said Goldblatt.

“When we shot at Lake Mirage, we could really do something with that exterior, because we could go for effect. I think we shot a great deal of the sequence on a 800mm with a doubler, effectively a 1600mm lens. With so much heat out there, everything was squirming and seemed out of focus, but it gives it a terrific, mysterious feel. I’m not a purist in the sense that everything has to look sharp. I would really prefer to go for effect or mood.”

Goldblatt used Panavision cameras for principal photography and Arri Ill’s for extra camera and high speed work. He shot with a full complement of hispeed spherical lenses ranging from 17mm to 1600mm. “Richard Walden, the ‘A’ camera operator and Steve St. John, the Panaglide and ‘B’ camera operator are both wonderful. I liked switching from the Panaglide for certain sequences and then returning to the more traditional camera moves. The Panaglide really helps bring an immediacy to the action sequences.”

Lethal Weapon was shot in 1:85:1 format. Goldblatt explains, “I didn’t want to go traditional anamorphic, primarily because I think the lenses are hopeless at any aperture below T2.8. I did want to shoot this in the new Super Techniscope format. You get the anamorphic format and you get the depth, sharpness and aperture of spherical lenses. It’s wonderful! Unfortunately, we were unable to use this format because of the extra step, a two to three week delay at the end of production for squeezing. We had to be done quickly. We finished mid-November and the studio wanted the release in the beginning of March. Another three weeks? Plus no time to go back to adjust. There was no way of knowing so we decided to go with 1:85.”

“I used Kodak 5247 rated at 100 and 5294 rated at 320 to 400. I was hoping to use the new Kodak 97 high-speed stock as most of this film was to be shot in low light or at night. I shot some tests with it, prior to principle photography. It’s the greatest thing going,” he enthused. “It’s sharp and has better blacks. We weren’t able to get enough stock for the film, unfortunately. With 5294, if you’re printing below 35 you’re in trouble, the blacks just don’t hold up through final print. It’s no use if dailies look good and the final thing is rubbish. You can rate 94 at 320 or 400 easily and be printing at 35... you’d better be printing at 35, and up! I’m really happy to be printing at 40 with 94. This nonsense from Kodak about 25 being mid-scale is rubbish, because they just don’t take notice of the failure of this film in the shadow area. The blacks degrade and it’s disastrous at that rating. Now 5247, I can print at 25 and no one will know the difference. But with 5294, a rank amateur would know that something’s gone wrong.

“Glover and Gibson are both terrific actors and [lighting them together] was a matter of sneaking in light at the right moments. Mike Strong, the gaffer, was very helpful to me in keeping his eye on that. I’d be watching the overall look and he’d be watching to make sure that Danny would be hitting that eyelight.

“We’d always be sneaking in little kickers to slice over Gibson’s shoulder and hit Danny so he would read. Mel was excellent in that regard and he would be careful to never shadow Danny and he wouldn’t hit the light himself because he would burn up. The more work I do, the more interested I become in sneaking highlights into faces, always working with a little bit of an eyelight, even a handheld one just to get it into the eyes. It was interesting and tough to follow that all the time.

“I remember once watching Sven Nykvist [ASC] work. One of the great arts of a cinematographer is to be able to NOT light, to specifically choose what you want to light and not light the rest of it so you get contrast, you get mood, you get atmosphere. So what if you can’t see certain things? What’s important is an overall feel. You must concentrate on the actors, you must make them look good, it’s your duty to them. By ‘good’, I don’t mean pretty but help enhance their telling of the story.

“For me, it was great experience to work with a good Hollywood crew and to work quickly considering all the stuff we had to do. We had major stunts and there were big, big lighting set-ups, but the crew was efficient and pleasant to work with.”

Goldblatt returned to the franchise in 1989 to shoot Lethal Weapon 2. Additionally, he has since been nominated for two Best Cinematography Oscars; in 1992 for The Prince of Tides, and again in 1996 for Batman Forever.

AC recently published this piece with the cinematographer, discussion his days as a still photographer in the 1960s and ’70s shooting The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, among many other subjects.