Celebrating the Life and Legacy of Sven Nykvist, ASC, FSF

ASC members Charlotte Bruus Christensen and Edward Lachman offer insight on the legendary Swedish cinematographer’s mindset and methods.

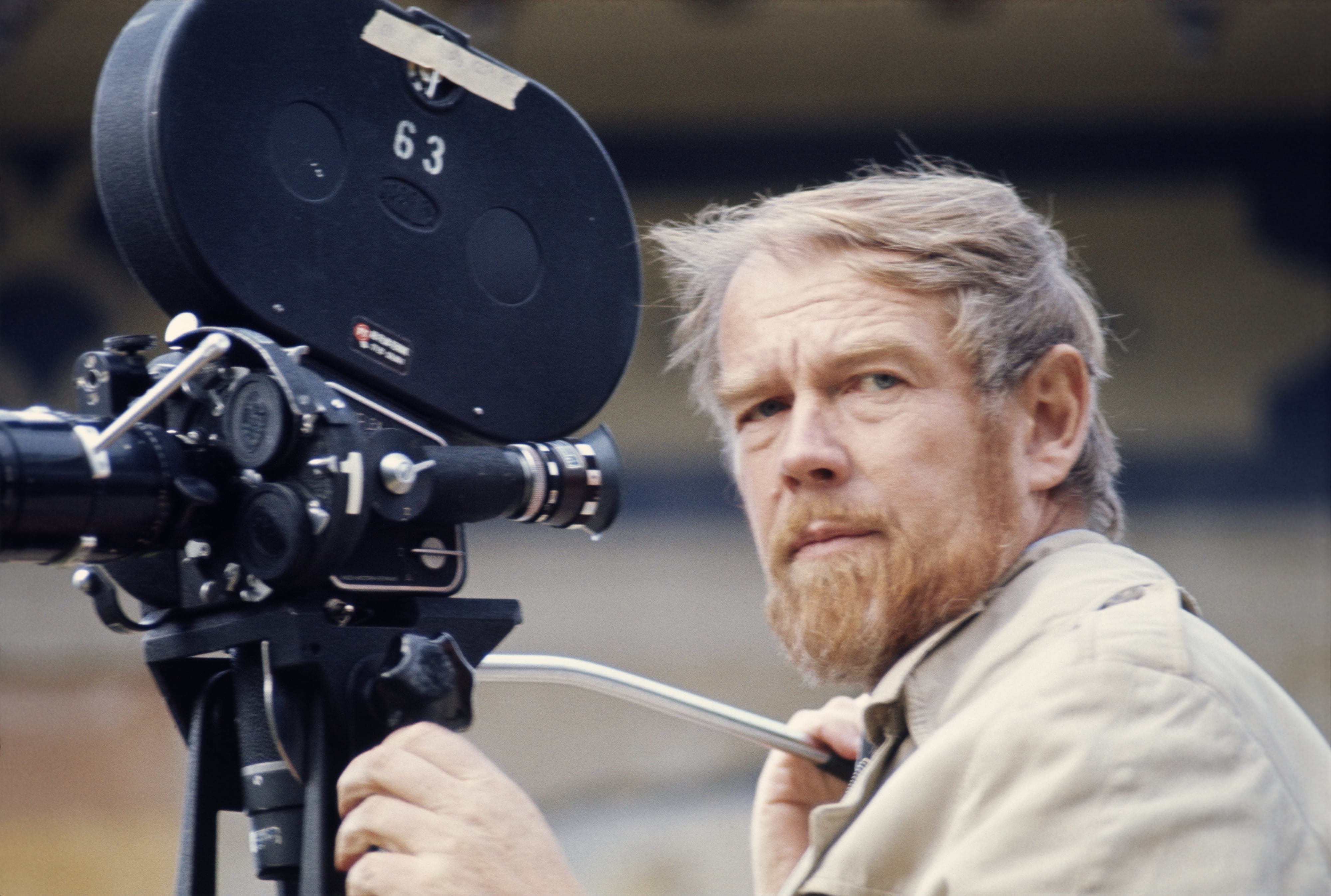

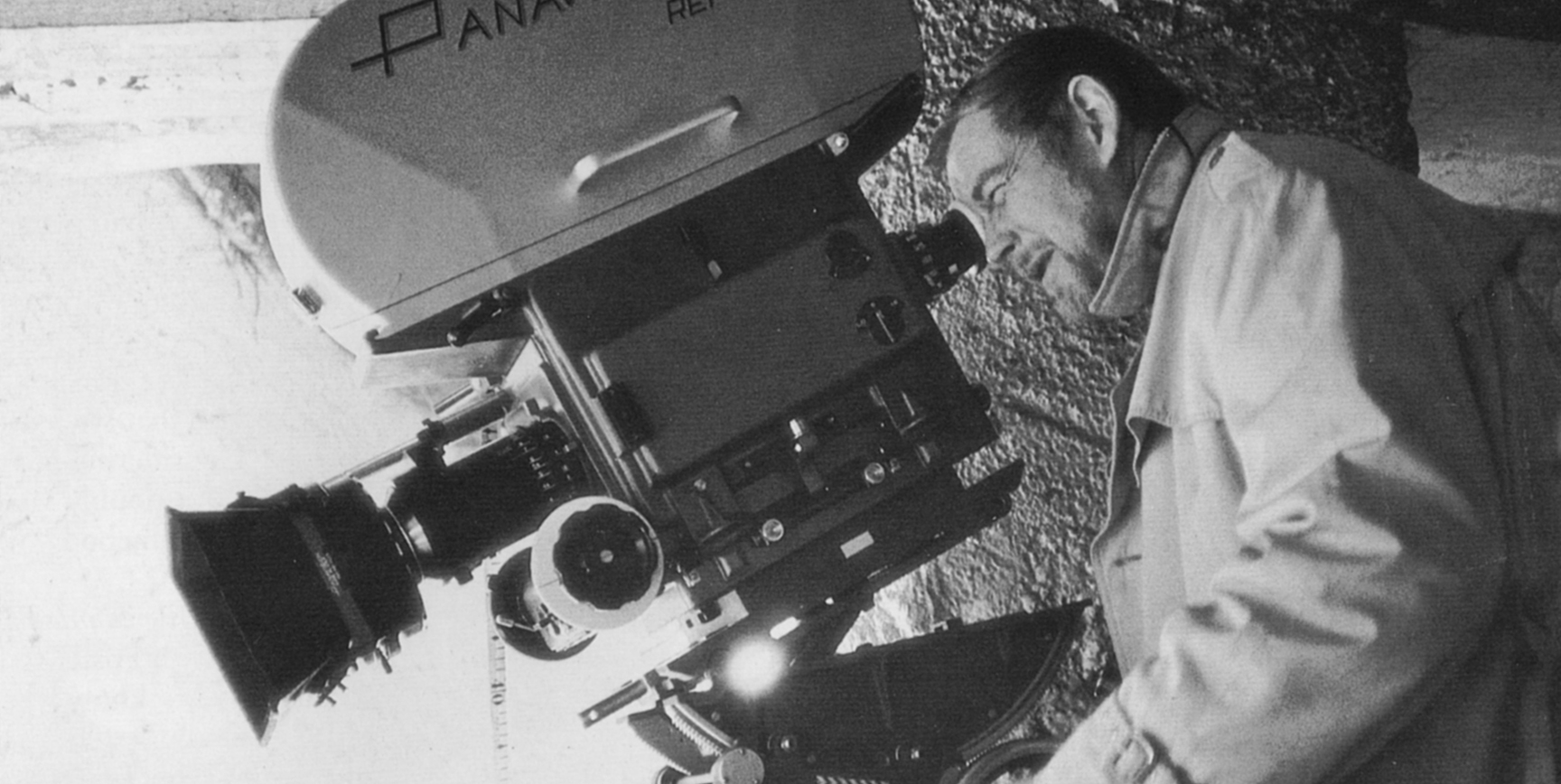

As part of an ongoing series showcasing the enduring work of influential directors of photography, American Cinematographer held a panel at the recent EnergaCAMERIMAGE Film Festival celebrating Sven Nykvist, ASC, FSF and his cinematic legacy. The panel followed a special screening of Cries and Whispers to honor the cinematographer’s 100th birthday. He was born on Dec. 3, 1922 and passed at the age of 83 on Sept. 20, 2006.

Film historian Lars Pettersson, FSF provided some biographical details: Nykvist began his career as an assistant cameraman for Sandrews studios in Sweden. He first worked with director Ingmar Bergman on Sawdust and Tinsel. They subsequently collaborated on some 20 movies over a 25-year period. Nykvist won Academy Awards for Cries and Whispers and Fanny and Alexander. He received the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 1996.

Pettersson was joined by ASC members Charlotte Bruus Christensen and Edward Lachman and moderator Benjamin B, who is a longtime AC contributor. ASC President Stephen Lighthill and CEO Terry McCarthy were among the attendees.

In his introduction, Benjamin B said that Winter Light marked a turning point for the filmmakers. Nykvist moved away from stark shadows and high contrast to employ a softer, motivated look, what Bergman called “a shadowless light.”

In clips from Ljuset håller mig sällskap, a documentary about Nykvist directed by his son Carl-Gustav Nykvist, Bergman and performers like Bibi Andersson and Liv Ulmann shared memories of the cinematographer. The famous “dream” sequence between Andersson and Ulmann from Persona followed.

Another extended clip from Persona found Andersson smoking by the wall of an outdoor patio. She leaves a piece of broken glass on the ground as Ulmann walks by. At one point, Nykvist pans from a closeup of Andersson to the broken glass and back. Nykvist conveys an extraordinary range of emotion without any dialogue. “Part of the appeal of the scene is that they take the time to build tension,” Christensen said. “It’s something we may forget in modern filmmaking, where we seem to focus more on ‘moving forward’ to entertain.”

For Christensen, the way Nykvist moved the camera, his pans and zooms, added an extra layer of nuance and creativity to Bergman’s direction. “In that first clip from Persona, the dream sequence, he does a slow zoom when Andersson is in bed and Ullman approaches,” she noted. “If you did that today, people would likely see it as a mistake. The feeling today is that the camera has to be perfect somehow. But there’s so much emotion in Nykvist’s work, even in the time it takes to pan from one person to another.”

Given Bergman’s vision for his film, and his blocking of the actors, “Nykvist still had a plan, he reacted with the camera with those little zooms you may or may not see.”

Nykvist was working on a three-picture deal with producer Dino Di Laurentiis when Lachman met him. In fact, Lachman became the standby DP on King of the Gypsies as Nykvist was not in the camera union at the time. Lachman then spent a year with him in Bora Bora as his operator a remake of John Ford’s The Hurricane.

“The camera is about point-of-view in the storytelling. That’s what Nykvist and Bergman understood. Where they place the camera creates the point of view for the audience.”

— Edward Lachman, ASC

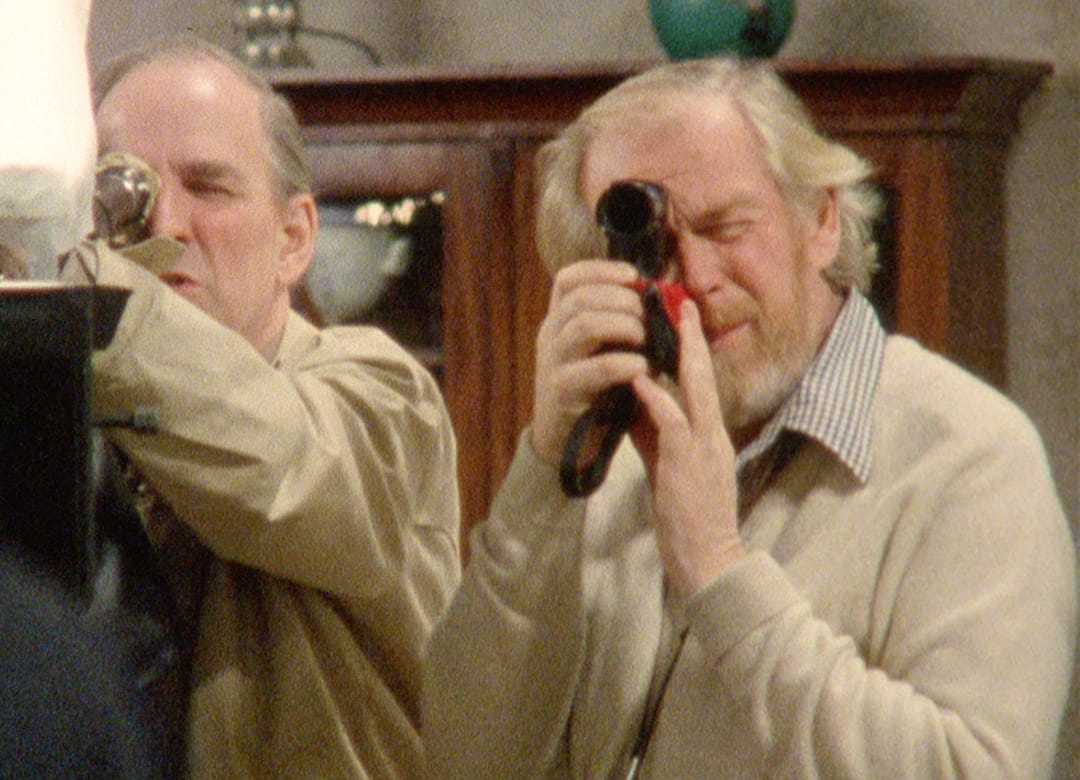

“I knew Sven was frustrated not being able to operate the camera in the US because of union rules,” Lachman said. “He joked to me that ‘Hollywood’s about making deals and matching action.’ On The Hurricane, of courseI was terrified operating for Sven, someone I admired so greatly. Also, director Jan Troell, who was a cinematographer himself, would come up with intricate and seemingly impossible shots.

“I would look to Sven and say, Would you like to do this shot?’ And he would go, ‘Ja, ja,’ and get on the camera and make these shots work. I was always astonished how he was able to operate with such grace and skill. Everybody talks about primes today, but he wasn’t afraid to use a zoom. He had no compunction about making adjustments with a zoom that created emotions within the shot.”

“You can say ‘adjustment,’ but you could just as easily be ‘intensifying,’“ Christensen added. “It’s minimalistic, it’s so simple and precise. And there’s that thing of putting the lens in the right spot, which is obviously a collaboration between the director and the DP. But really, that’s what we’re all looking to do, you know?”

“The camera is about point-of-view in the storytelling,” Lachman said. “That’s what Nykvist and Bergman understood. Where they place the camera creates the point of view for the audience. The camera is another actor. It’s acting and reacting. It’s about the emotion. Why Bergman trusted Nykvist is because he was another great actor in the scene. You feel the emotions through his movements.”

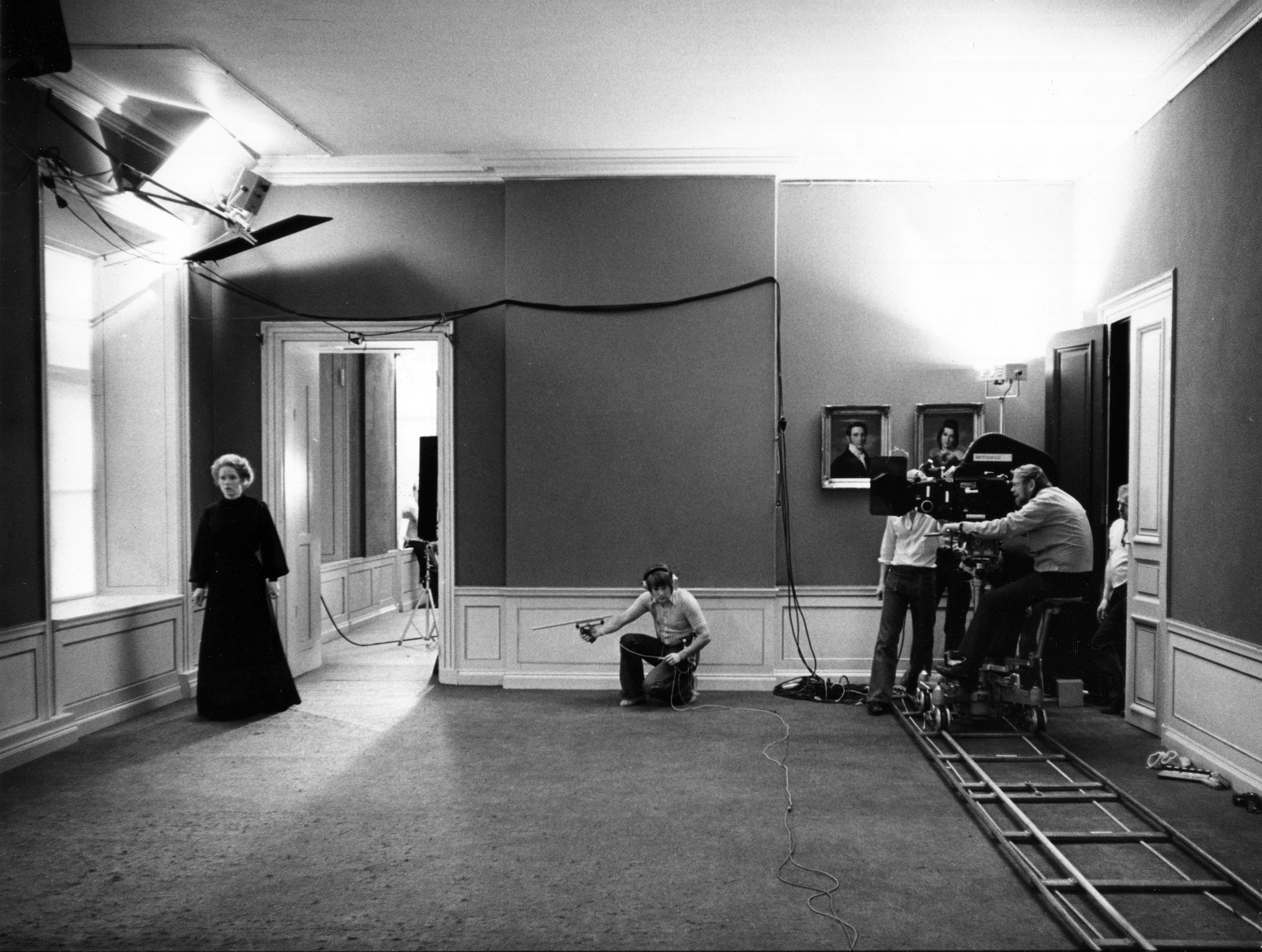

A clip from Cries and Whispers, Bergman’s first film in color, showed an extreme closeup of Ulmann as Maria and her former lover David (Erland Josephson). As they stare at a mirror, Nykvist’s camera helps shift the meaning and balance of power in the shot.

Lachman recalled how Nykvist’s Swedish camera crew would rarely take marks for the actors’ movements. Instead, they would mark areas on the floor, giving the actors more freedom in their performances.

“Sven used a Pentax 5 spot meter, the same light meter I still use today,” Lachman said. “He would always light from the face, adjusting the stop for what the look on the face should be. He wouldn’t light the set without consciously thinking about where he wanted to place the exposure on the face.”

“That’s lost a bit with digital because we perhaps don’t think about lighting in a mathematical way, the way you do shooting on film,” Christensen said. “There’s an order to how you light, how you build your image with background and foreground. On celluloid we do that by eye and by light meter.”

Asked how Nykvist would light a set, Lachman answered, “Where someone would use a 10K, he would use a 2K soft light. Gaffers were always surprised. They’d bring in these big directional sources and he would turn them around and bounce them. He loved to create a soft bounce light as his main source.”

“The collaboration between blocking and camera moves, or not moves, is something we discover down the line,” Christensen said. “You have a core, a heart of a scene, and you build out from that. That extreme closeup from Cries and Whispers, it’s also about blocking. You don’t see the mirror, you just know it’s there because they talk about it.

“Sven does a little zoom again,” she added. “It’s not like a set closeup, you constantly feel his breath. It’s moving, it’s alive. To hold a closeup that tight for so long, where you hardly see the lips — the shot needs to ‘intensify’ and sustain the drama. Nykvist does exactly that. You’re somehow watching their thoughts through the lens.”

After clips from Scenes from a Marriage, Benjamin B wondered if cinematography could be ugly or boring. “I would turn that around and ask, ‘What is beautiful cinematography?’” Christensen replied. “You can say the exposure here is pretty much the same in the background as on the face. It’s pretty evenly lit, but I think it’s great. Beautiful cinematography doesn’t need to be postcard pretty, you don’t need perfect lighting setups with a beautiful rim and shadows and highlights. I don’t think it’s the most extraordinary cinematography I’ve ever seen, but the scene is so moving and precise.”

“Aesthetic beauty isn’t necessarily a requirement for good photography,” Lachman offered. “We see the characters through a doorway, like we’re eavesdropping into something we shouldn’t hear. It’s about the director’s point of view, where the cinematographer places the camera. If you can help an audience find the emotional content of a scene, then that’s what’s beautiful.”

“Another thing about this clip is that we all constantly have to find the rhythm,” Christensen said. “It’s simple — there are the closeups, the beautiful framing of the door — but it’s also the rhythm of the operating and movement. When Ulmann comes toward the camera, he pans and zooms, the door slams, she reacts, and he ends the zoom right there. You feel what she’s feeling. To me, that’s beautiful cinematography, despite the fact that it isn’t breathtaking imagery.”

“I agree, but I would replace ‘beauty’ with ‘authenticity,’“ Lachman suggested. “I think that’s what we’re always looking for with the director, the art direction, the performances, and the images. Does the audience believe the situation you’re creating? Music has rhythm, but images have rhythm too. If you’re in sync with an actor, it brings the audience closer to the performance.”

During the question-and-answer period, a film student from the Czech Republic asked if the pressure of blockbuster budgets affected their work. “It’s a very good question,” Christensen answered. “The studio movie world is a massive machine. It’s almost scary to down-tune. Producers want to live up to the fashion of the moment, audiences have expectations, and cinematographers have to match those expectations. If you try to do something ‘different,’ you might very well get called ‘arty’ on a big set.

“I don’t think that’s an excuse,” she continued. “It’s a matter of making decisions, focusing on the story. We need to stay loyal to the script and to ourselves. There should be room for big Marvel movies, but also for personal ones.”

“There are different kinds of filmmaking,” Lachman said. “I won’t use big-budget Hollywood films in a pejorative sense, because that kind of filmmaking can take place anywhere in the world. Those kinds of films are often shaped by financial imperatives. It’s the uncompromised vision of directors and their teams that makes compelling films at all budget levels — like those here at Camerimage.”