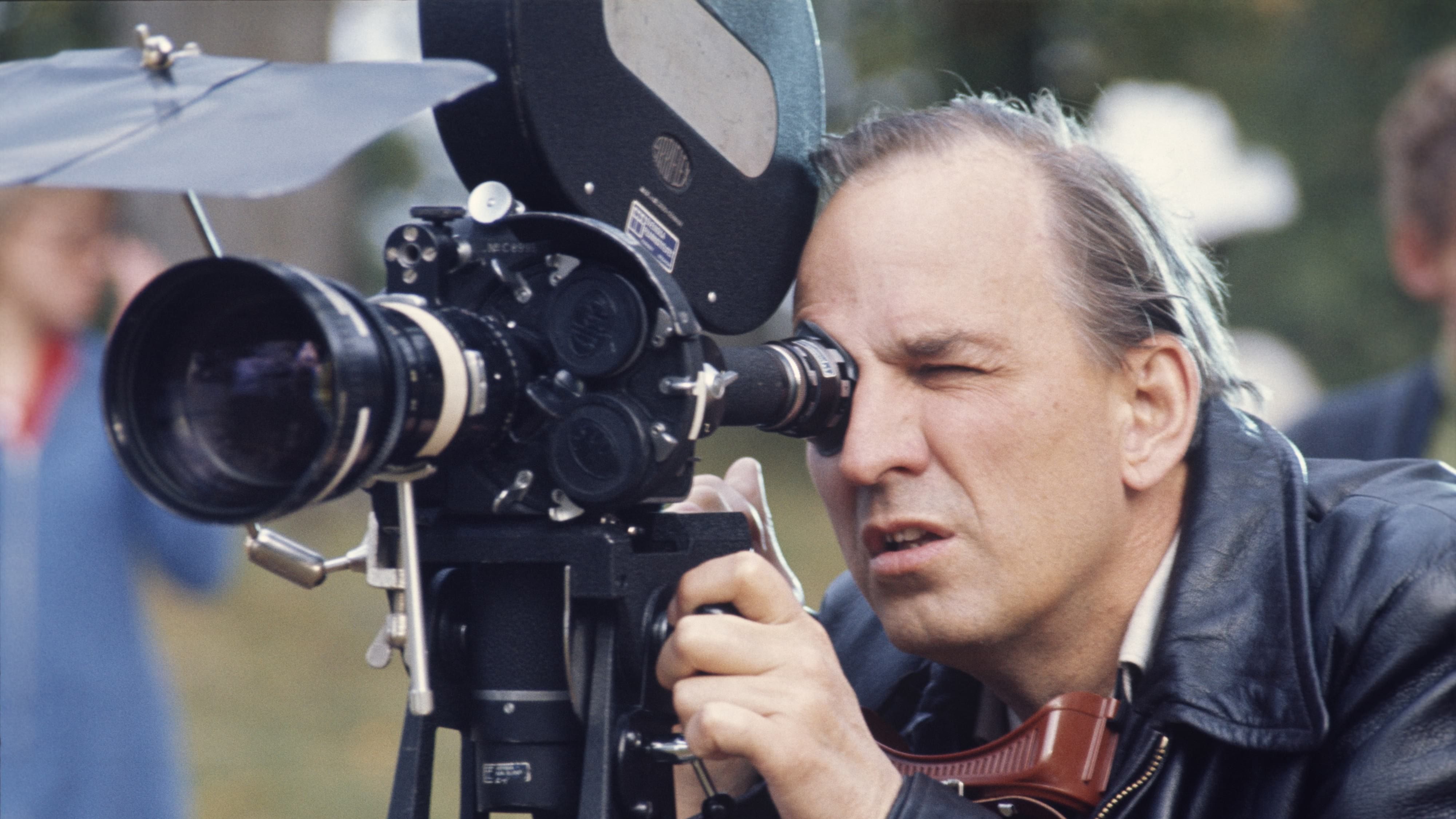

Photographing the Films of Ingmar Bergman

In striving for realism in his photographic lighting, Bergman’s cameraman finds the new, fast black-and-white emulsions extremely helpful.

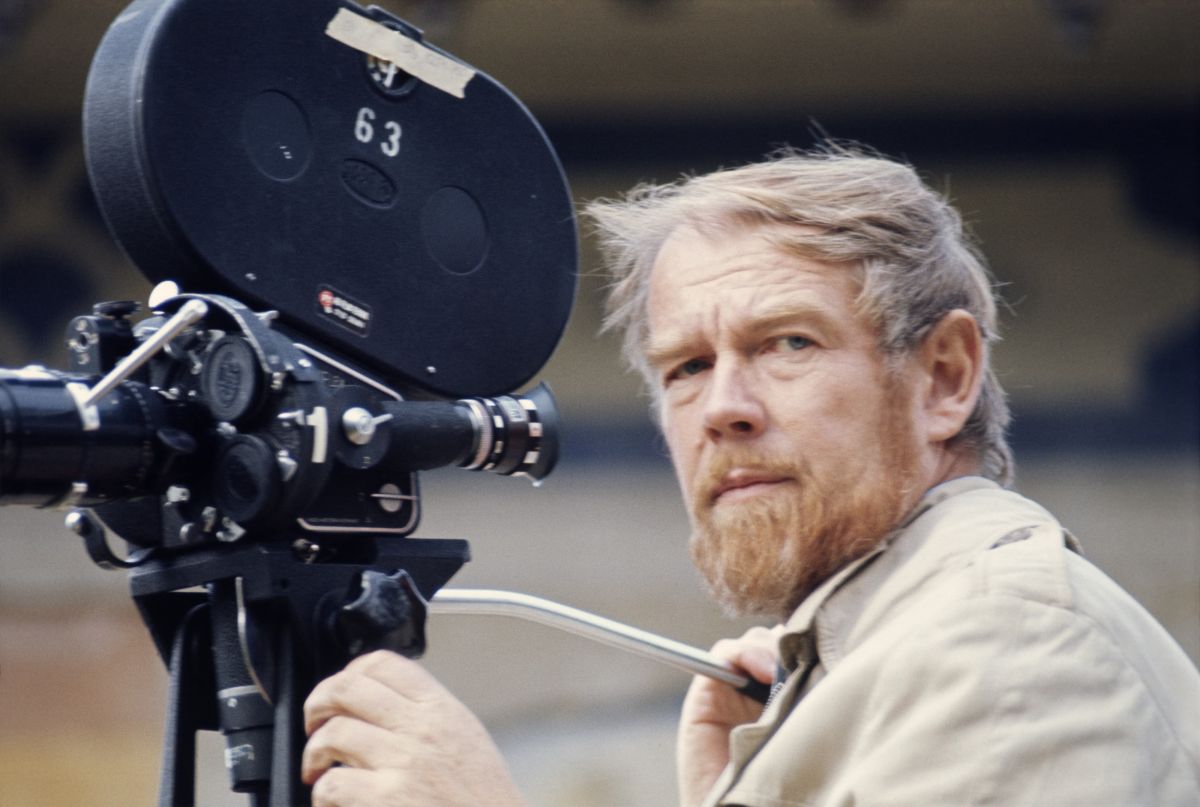

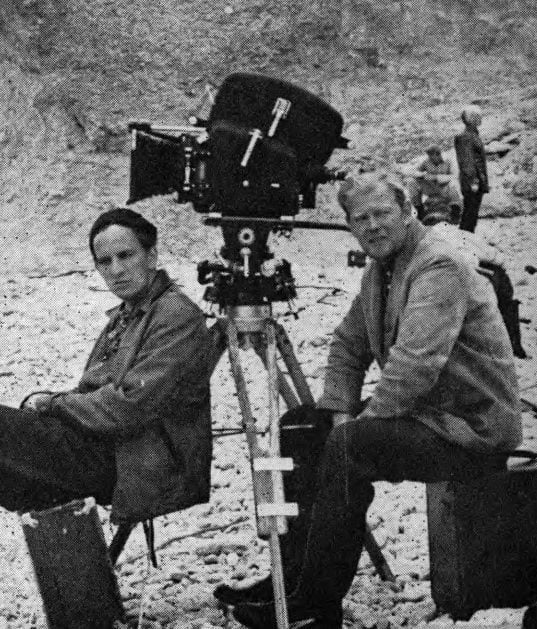

By Sven Nykvist

One early summer morning this year a group of Swedish filmmakers gathered at Hotel Siljansborg, Dalecarlia, Sweden. The sun glittered on the surface of Lake Siljan as we lingered over our coffee on the terrace. Presently we left the terrace and gathered in the bridge room, which now became a session room for our film production conference.

Assembled were art director P. A. Lundgren and production manager Carlberg. There were makeup man Borje Lundh and his wife, costume designer Marke Vos. There were prop man K. A. Bergman, and Katinka, the script supervisor. And finally, director-producer Ingmar Bergman and myself, chief cameraman.

Katinka began reading the first page of Ingmar Bergman’s script of The Silence, which we had assembled there to discuss. She had not read far when the first question was fired at Bergman: What kind of effect had he imagined at this point? How should he reach it?

It was not by chance that we had gathered in this part of Sweden. Hereabouts were the nature and the people still keeping his childhood memories vivid for Bergman; as a child, he had spent all his summers here in Dalecarlia. And the landscape held many memories for the rest of us, too. On the first evening of our visit, we traveled to Styggforsen where we had filmed The Virgin Spring in May, 1959. The following evenings, we visited the little village where the very lengthy scenes in The Communicants were shot during the autumn months of 1961. (This feature, now completed, is scheduled for release in January, 1963 —probably under a different title.) [The film was released in February 1963, under the title Winter Light. -Ed]

But back to Bergman’s script. It took us four days to fully cover the script, line-by-line. I have only once before encountered similar accuracy and diligence in production pre-planning and that was when I worked with the German director Kurt Hoffman [Snow White and the Seven Jugglers, 1962 - Ed.]. Such meticulous care might be construed as formalism and lavishness, but it saves a tremendous lot of time and money. Ingmar Bergman knows this by experience. In keeping with his growing position as a producer, he demands more planning activities preceding his productions. And this careful and exacting planning means much for his co-workers, too. Instead of going abruptly from one production to another, we are given time in which to acclimatize by emerging leisurely into the very special atmosphere which Ingmar Bergman builds up for each of his productions.

The collective discussions, such as we had that morning at Dalecarlia, were quite naturally followed by individual chats by Bergman with the various members of his team. The art director was asked to build a special test room in the studio; here the costume designer would test the various textiles to be used in the picture. The makeup man was asked to begin a series of screen tests to determine the suitability of certain characters and to study the results of different makeup materials. And when I returned to the studio, I commenced a series of tests of film emulsions we considered necessary for the photography of The Silence.

In this production, two women and an 11-year old boy arrive in a foreign city. They are depressed by a feeling of impending danger as in a dream, and are unable to communicate their fears because they do not speak nor understand the language.

When Bergman handed me the script, he explained the dream effect he wanted: “There must not be any of the old, hackneyed dream effects, such as visions in soft focus or dissolves. The film itself must have the character of a dream.”

Bergman believes in photography having high contrast, so my preparations for this dream effect began with a series of experiments with different kinds of him emulsions. We were surprised to discover the strong graininess effect we obtained from our experiments with 16mm Ektachrome Commercial blown up to 35mm black-and-white. We also made photographic tests with ordinary sound recording him and with orthochromatic emulsions, and all these tests included the films of various manufacturers.

The conclusion reached through the tests was that each him and each laboratory method employed offered some of the advantages we sought. Our final decision was to shoot with Eastman Double-X negative and develop it to a higher than normal gamma.

When I started to work with Ingmar Bergman on The Virgin Spring, I met a director having a passion for light — a passion for light and light effects similar to that of Alf Sjoberg, who directed Miss Julie. Sometimes I have wondered if this passion is not the result of all the years they have spent as stage directors. On the stage they had unlimited freedom to develop their ideas about lighting, and I believe this sharpened their instinct for pictorial lighting effects which both directors have displayed in their films.

My own record as a cinematographer includes some 40 feature-length films, having started my work behind the camera at the age of 18. As I look back now in retrospect on all the tricky experiences I have had in filming 40 features, I am sometimes appalled. I am reminded of effectively lighted spots and a swarm of double shadows on the set walls. I see needless backlighting on a beautiful woman’s hair; and big, exaggerated foregrounds — made only to create a great dramatic perspective in the picture. In short, what I see is overworked pictures — pictures made only for the picture’s sake.

Ingmar Bergman and I promised each other, when we started with The Virgin Spring, that there would be no beauty effects. “Here,” we reasoned, “we have a legend from the 11 century. Let us tell it as realistically as possible.” This we sincerely tried, with all the means available to us at the time — which was before the advent of Double-X film.

After this first co-work with Bergman, I have met every new production as a new and interesting challenge, a chance to move a step forward. The goal has always been the same: to keep it simple.

When Through a Glass Darkly was shot on the island of Gotland in the Baltic Sea, we traveled daily between the camps and the location in the early cloudy-gray light and we noticed how many fine, impressive graphic values were to be seen, and that whenever the sun broke through the overcast momentarily, how it instantly killed the many delicate shades of light, arresting the graphic play between highlights and subtle shadows. The tone we were aiming for in that production was a graphite tone — photography without extreme contrasts.

The next time, with The Communicants [Winter Light; 1963], we went a step further. We made systematic light studies, as we were curious as to the true sensitivity of the new Eastman Double-X negative, which promised to enable us to achieve more and finer gradations.

The story was to be enacted between noon and 3:00 P.M. on a typical cold and cloudy Nordic day in November, with sleet in the air. The picture was meant to be as shadowless as a cloudy day really is. We traveled around Dalecarlia, looked over some 30 churches located around lake Siljan, and photographed each one inside and out. Finally we chose Torsang church. We then gave this church intensive study during the number of cloudy days that prevailed at that time — September, 1961 — and we observed particularly how the light changed inside the church from hour to hour. We recorded with a Leica camera the interiors at various times of day as the pattern of the light traveled through the empty old church. The resultant prints I pasted in my copy of the script, and they were of inestimable help to me later when lighting the set of the church interior, constructed on a studio sound stage.

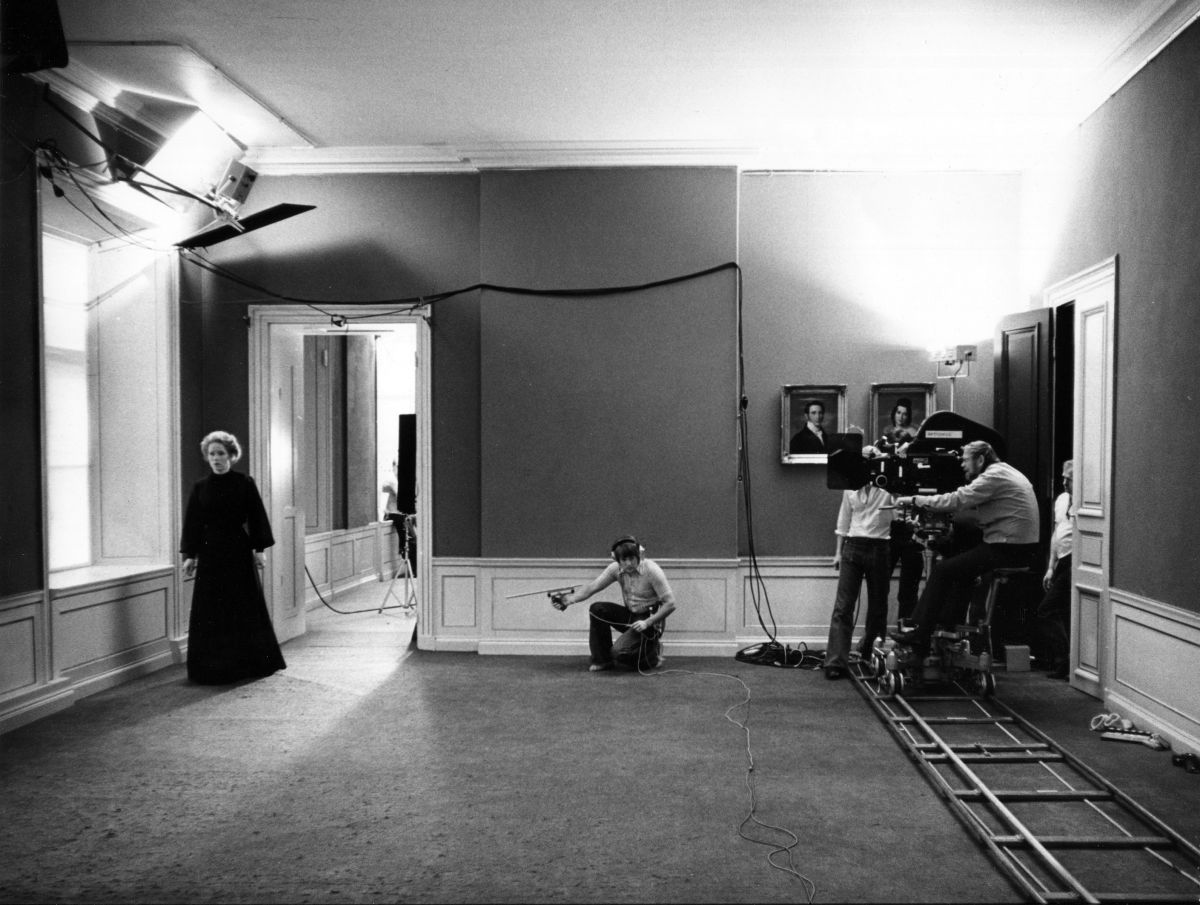

For Through A Glass Darkly, 250 scenes, representing a quarter of the production, were to be actually shot in the Nordic summer twilight. So we organized production work on the location thus: ordinary shooting was to be terminated daily at 3 P.M., at which time the twilight scenes were rehearsed for three hours, so that all who were involved — actors, cameramen and technicians — were fully informed as to what they were to do during the short, 10-minute shooting period that would be available to us in the twilight. Thus we worked daily for three weeks to photograph vital scenes during the brief twilight of Swedish summer nights. Usually, we were able to make an average of three different shots during the 10-minute twilight period. For The Communicants, we were able to shoot for longer periods, thanks to Double-X film which by now was available to us. If we had had this film when we photographed Through A Glass Darkly, we could have completely avoided the troublesome double shadows that resulted whenever an actor crossed a set. Now, with the faster film, we could achieve true, shadowless lighting with indirect light. For this, simple frames were constructed over which were stretched sheets of heavy waxed paper to diffuse the light. By thus eliminating all direct lighting, we created the natural shadowless aspect of a cold, frozen day in November.

operate the camera.

As the main part of this story takes place in a church, the church interior was built at the studio. Even the ceiling was included and we had to rely entirely on indirect lighting for photographic illumination of the set. When the final scenes were shot on location at Dalecarlia, inside the actual church, I realized how fully sensitive the new emulsion really was. The pictorial mood had to follow faithfully the gradual darkening of the day outside, and in one of the shots the only artificial light was from a huge, seven-armed candelabra. Augmenting this was fill light from a few 500-watt lamps. With this illumination, we achieved lighting in the scene that was highly realistic — simple and without effects.

I am grateful to Bergman’s scripts that his photographic goal always changes with each one. There is no possibility for his cameraman to just alter his ordinary routine lighting technique or to shoot production after production in the same manner. All easy-come effects must be sacrificed for the simplicity which does not disturb. Although public acclaim in cinematography often can be achieved by instantaneous effects, it is in the long run only the true light which is interesting and which I strive for more and more in my work.

You might say that the study of true, natural light as we actually find it in our daily lives, is a passion with me. For instance, there is a long narrow corridor outside our studio projection room, both ends of which lead out into the open. While sometimes waiting for the “dailies” to be projected. I sit and study how the daylight is spread out on the floors and the walls. Such reality is always around us, affording lessons in lighting technique if we have the patience and the time to observe it.

And who doesn’t want to, with new and faster films constantly being made available to us, which enable us to achieve new and interesting graphic results on the screen?

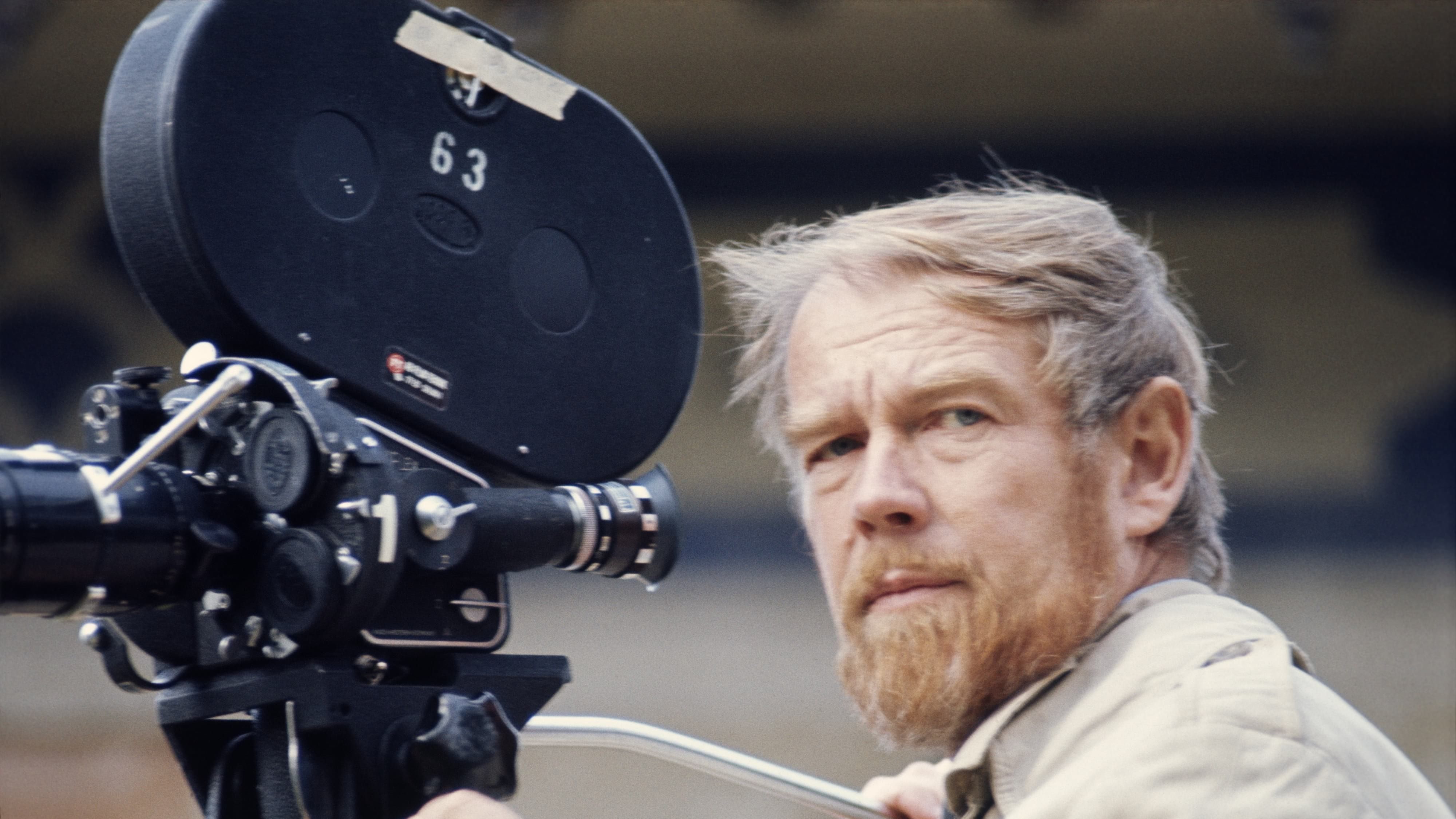

Nykvist would go on to photograph numerous films for Bergman, also including All These Women, Hour of the Wolf, The Passion of Anna and The Serpent’s Egg. The cinematographer won his first Academy Award for his work in their film Cries & Whispers (1972). He earned his second Best Cinematography Oscar for Fanny and Alexander (1982), the director's last feature film.

In all, with more than 120 credits to his name, Nykvist was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 1996.

He was 83 when he died in 2006.