The Problems of Lighting and Photographing Under Capricorn

“I viewed the job ahead with as much tranquility as a premeditated fight with an octopus! Looking back on it all, I’m not so sure I wouldn’t have preferred the fight with the octopus.”

This article was originally published in AC, Oct. 1949. Some Images are additional or alternate.

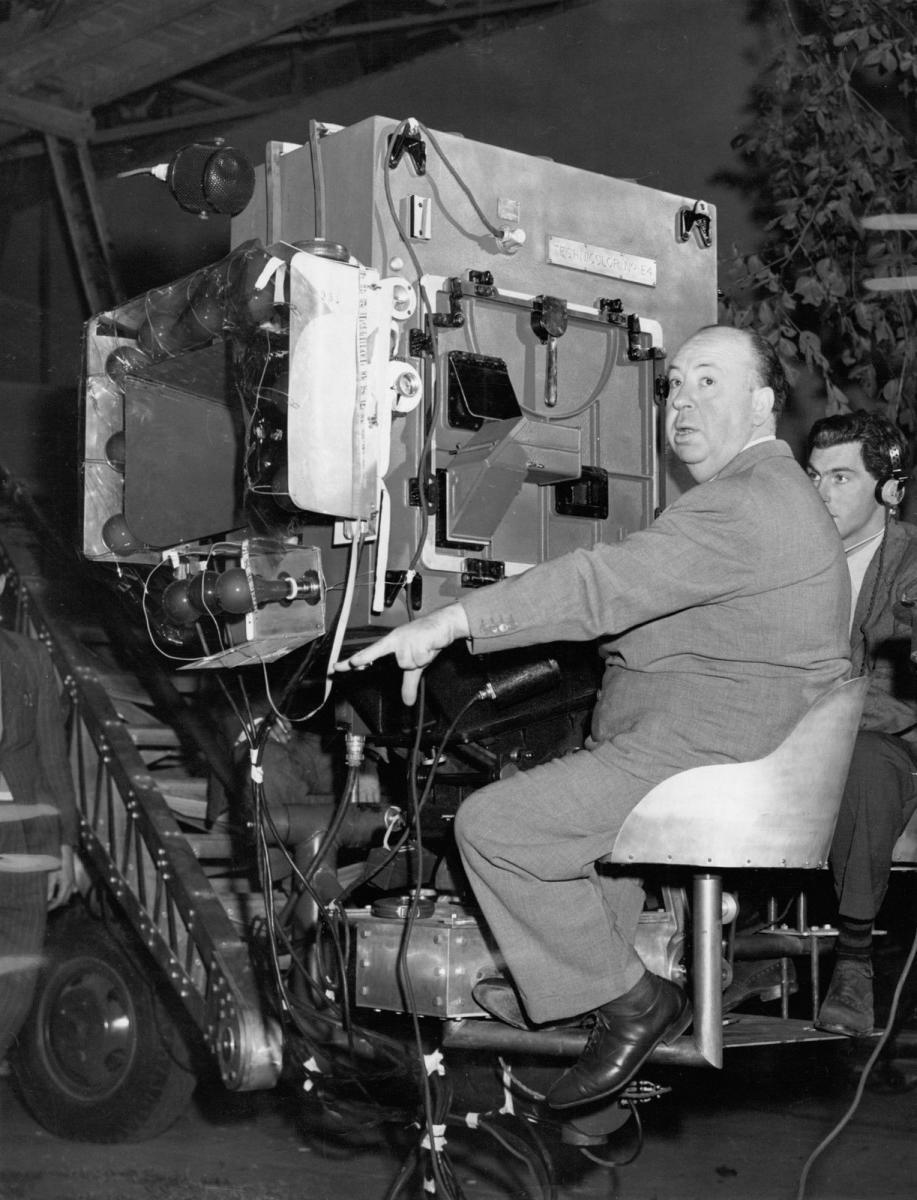

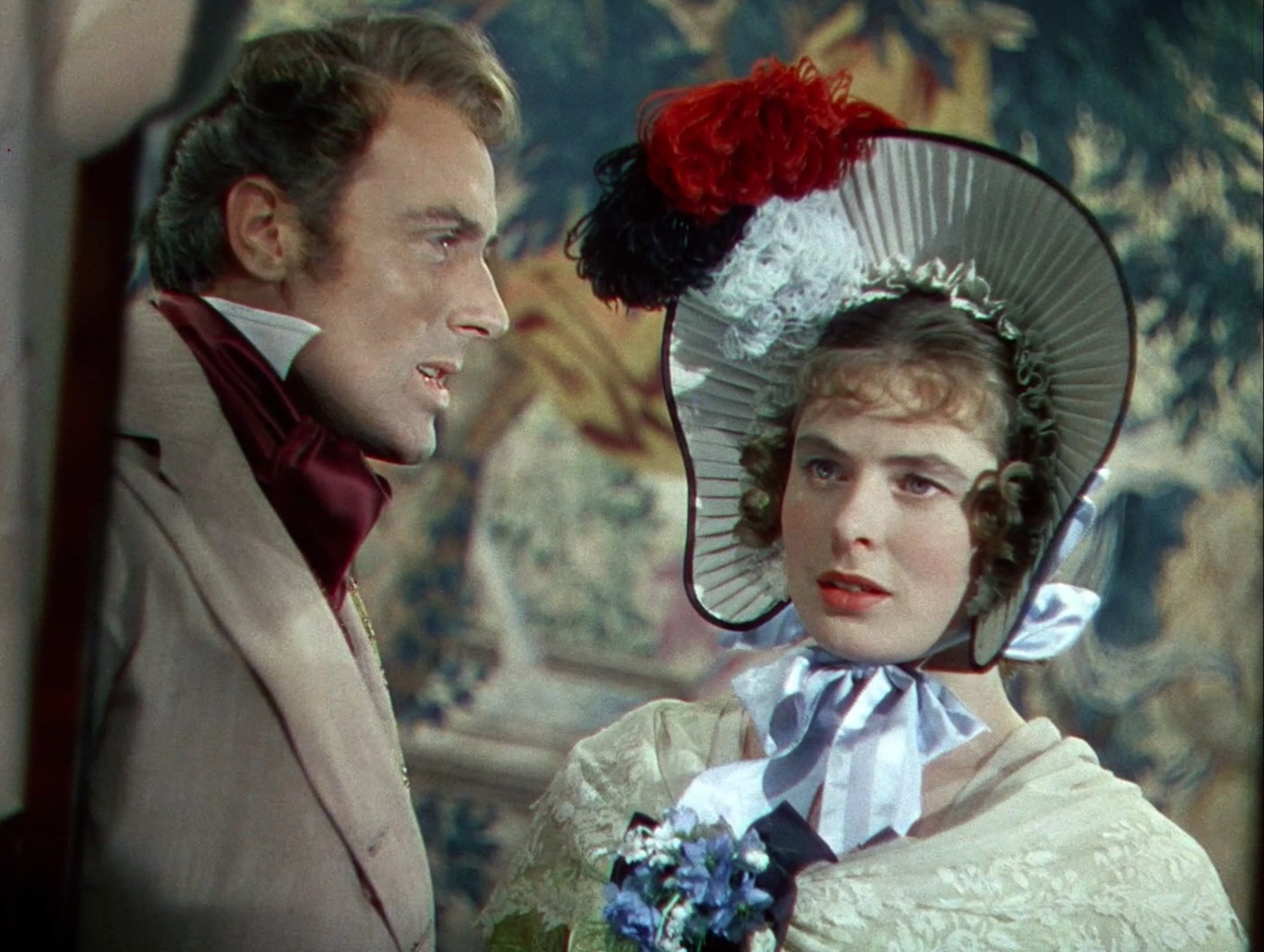

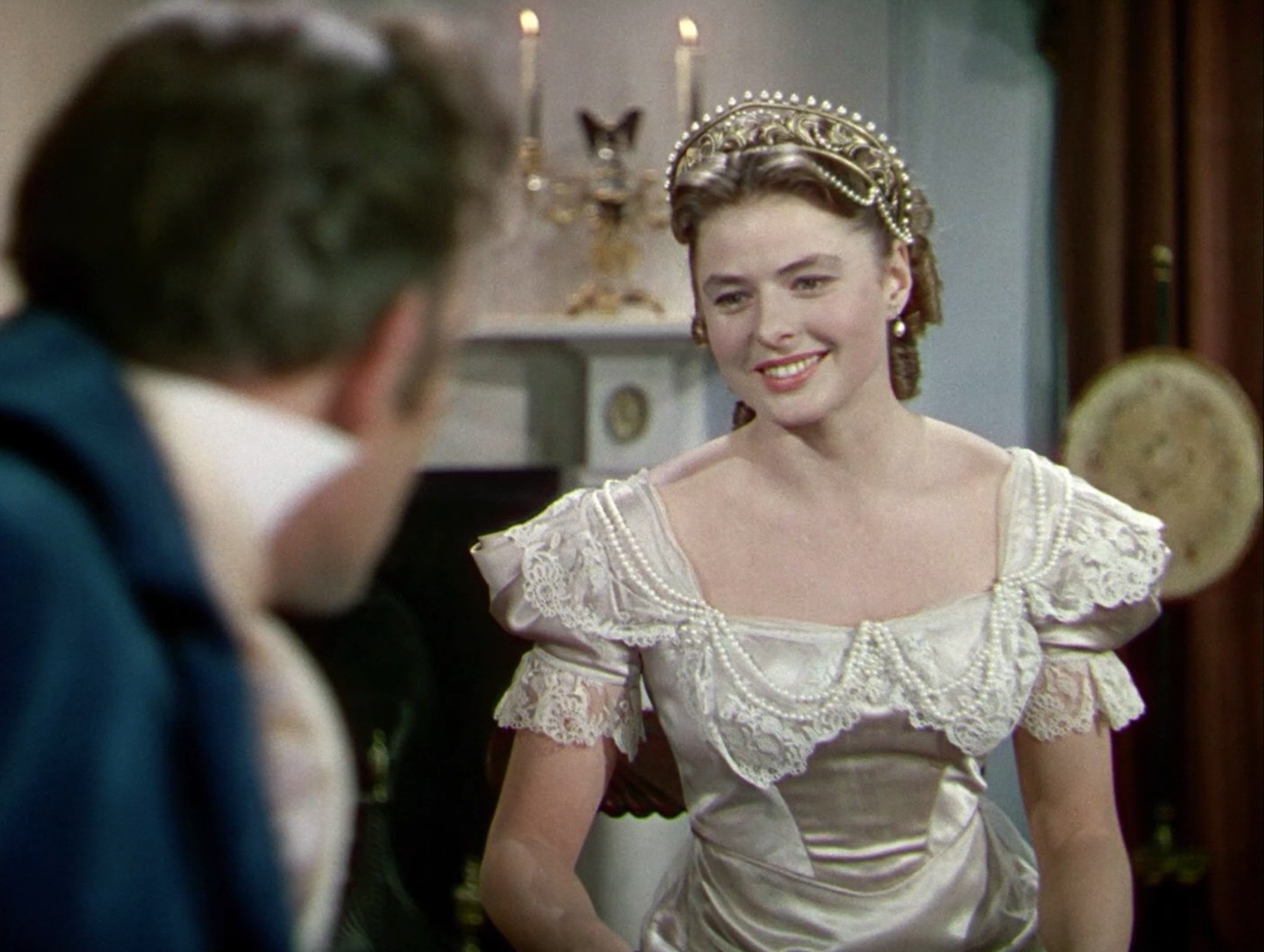

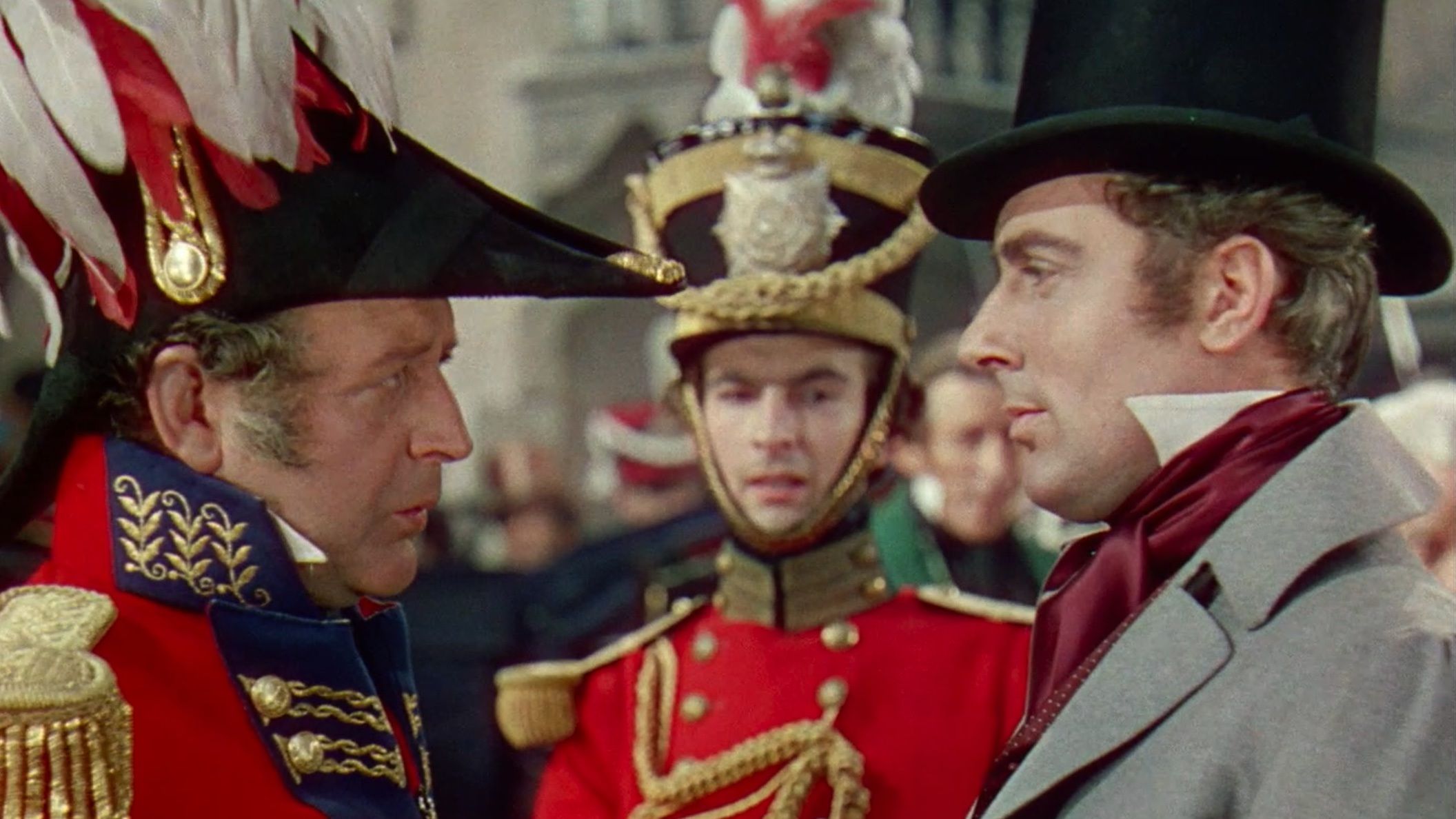

I should have known better. An assignment with such a zodiacal title as Under Capricorn should have warned me not to be too elated at face values; but when the face was Ingrid Bergman’s and the director Alfred Hitchcock, I surely couldn’t help hugging the Capricornus goat, dreaming cozily of big, big, close-ups of La Bergman, and devising cunning gymnastics with Hitch the Master.

Of course, there was a catch — a deadly one.

To illustrate: “I want a cameraman. You there, Al Splonks, ASC, will you come up on the stage a moment? Thank you.

“So you think you’re good? Right. Here’s Miss Bergman. Apotheosis of beauty: perfect bone structure, cheek bones that camber exotically, eyes that smile right through a thin negative, and the supple-firm lips of Aphrodite. Now, Mr. Splonks, she’s all yours. You can paint her with lights; a big, big, close-up. At least you start with a big close-up; then you must track way back to a long shot of a dining room, track and pan around for a few minutes, track into a few other rooms… Yes, that’s what I said Al, say about five other rooms, including a circular stairway into a room upstairs, back again, and down into the dining room. Yes, that’s one shot, Al.

“Remember Rope? Well, this is the same technique, but with a composite six-room house and we move through walls that open into, something, as many as six rooms in one scene.

“As you see, it calls for a 35mm lens, so for Miss Bergman’s close-up your camera must be only about 18 inches away from her face. Yes, Al, a 35mm lens is not very good for a close-up. You want to use a 50mm? Well, I did, too, but think of those other five sets we go into, Al; so for this one we’ll have to use a 35mm. Yes, that’s a Technicolor blimp — big isn’t it? And when 18 inches away from a beautiful face, there isn’t much room. Why the lens shade practically touches her nose! Well, you must manage somehow; there’ll be trouble if we throw away our lens shade!

“Now, all your special little lamps for close-up lighting must fly away as we track, and they have to fly really fast to beat that circuitous electric crane and the electric fly-away walls, and the ceilings that lower into place, and the table, cut into 14 sections, which frantically jigsaws in and out of position as we surge through it — backwards and forwards! Oh, another thing, Al. Miss Bergman mustn’t look too beautiful in the first few reels — she plays a wan dipsomaniac… You too, Al? Well, let’s open another bottle before we start the next scene.”

Now that Under Capricorn is just a memory, I can view it with a wider perspective, especially as I have just finished a movie employing the antithesis in technique Black Rose has only one dolly shot in nearly 900 scenes!

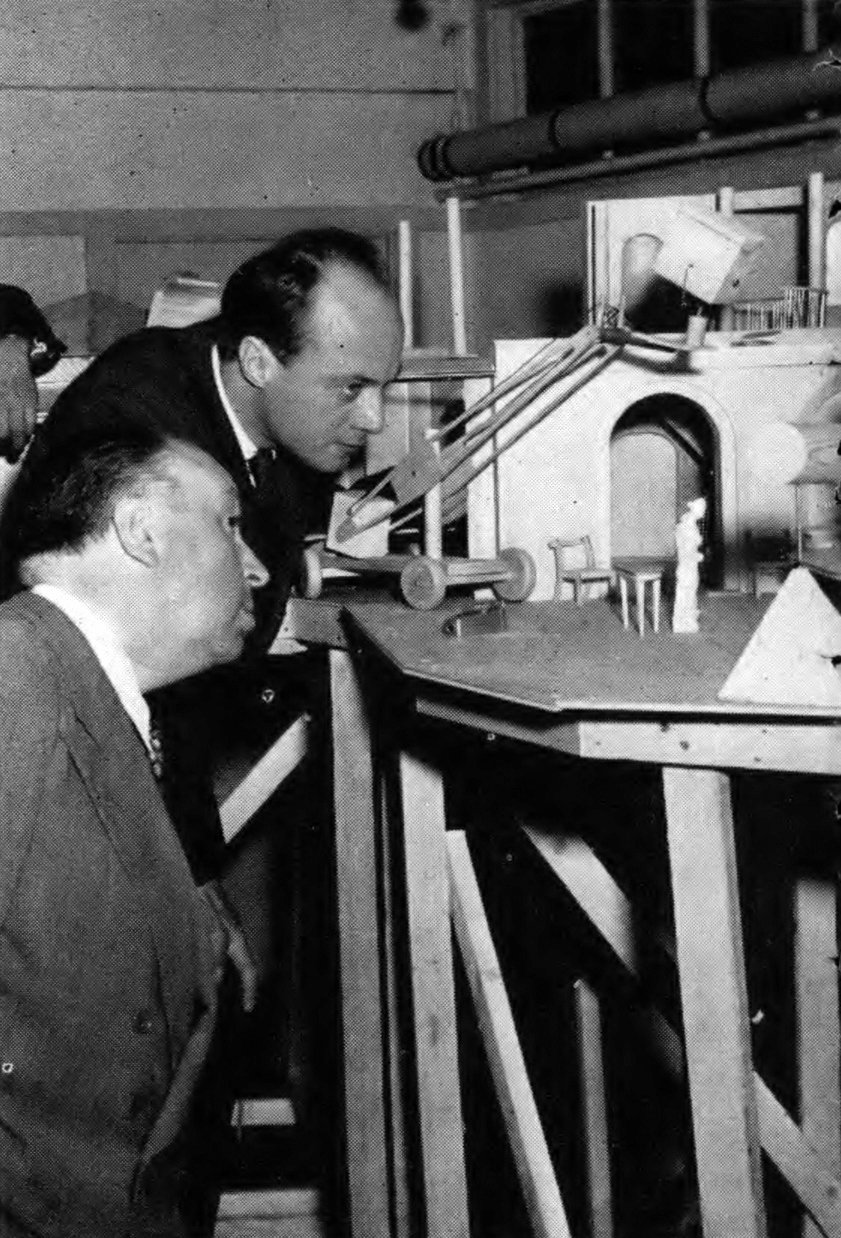

We prepared Under Capricorn in the ideal theoretical manner. It started with a three-man conference: Hitch, art director Tom Morrahan, and myself.

For one week we listened to Hitch outline the plot, and watched his expressive hands draw every set-up in the picture on paper already prepared with frame lines. Hitch always places the positions on faces first, as he considers that framing a correct pattern of the principal faces on the screen is a most important part of dramatic structure.

With a swift and confident movement, he makes a simple oval for a face, with a T form to represent nose and eyes; placing the T either in the center or on one side, to either in the center or on one side, to represent full face, or three-quarter, and it is astonishing how concise this method of face-structure can be. Then the background is drawn in, and at the end of each sequence — or reel — the art director and myself have made copious notes effecting economy of set building and lighting arrangements.

We continued our planning with a large model of our composite set, using scale actors, furniture and even scale lights. With a perfect miniature replica of our crane we mapped out every camera movement exactly, so that at least we knew what we were up against, and I hardly need to say that I viewed the job ahead with as much tranquility as a premeditated fight with an octopus! Looking back on it all, I’m not so sure I wouldn’t have preferred the fight with the octopus.

I shall only say that it was a technical nightmare I wouldn’t have missed for worlds!

A normal studio floor was useless for smooth and silent dollying in any direction so, as on Rope, we had to build a special floor. But of course our area in this case was much greater for a large Georgian house and garden. First a two-inch thickness of asphalt was heating and set over the floor, then came a layer of felt, and this was in turn covered with carpet. Imagine, at austerity time in England with carpet strictly rationed, we covered our studio floor with one huge carpet, which measured 150 feet by 80 feet! Our composite set was now built on the carpet and it was really a work of art, with practically every wall and even ceilings made to move silently away at the press of a button. This floor, silent and level both outside and in, was not treated for various surface effects, i.e., Aubusson carpet, marble, gravel exterior, etc.

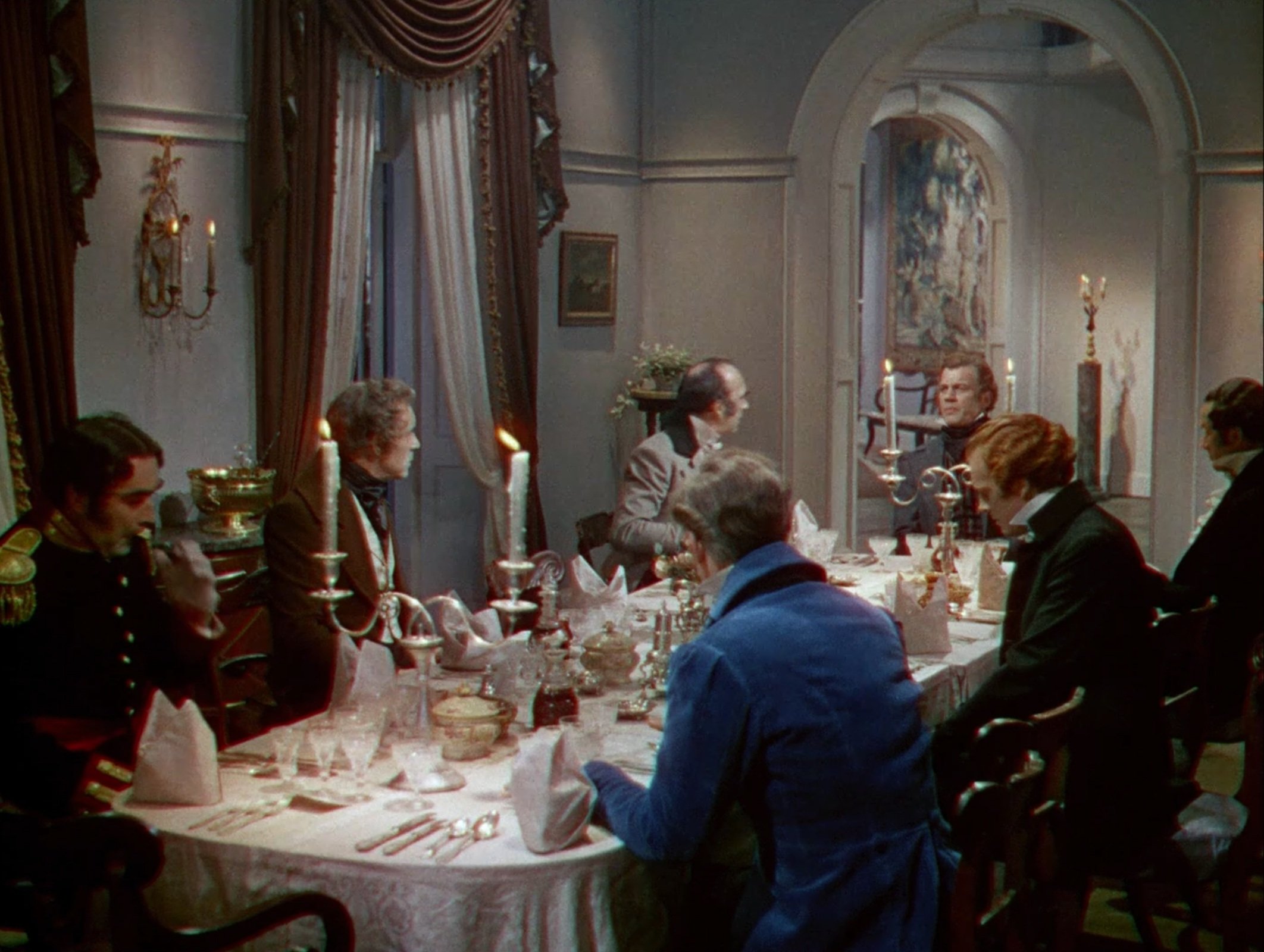

As I mentioned earlier, we cut a large Regency table into 14 divisions, laterally and vertically, so that we could crane right through it as if it didn’t exist. Each division was snatched away at the very last second as the crane surged through in hot pursuit of the actors prancing from room to room.

This was a noble sight: a gang of men frantically dodging the camera in a mass like a football scrum, each with a tiny section of a table in his hands. The actors often helped and as the camera approached them seated nonchalantly enough, it looked positively weird to see them suddenly grab a section of a table, with a candle or a plate of food fixed onto it, and fall wildly out of picture into the perspiring melee with their own parts of the table clutched in their hands.

The rigging lamps was also a headache. More than 200 lamps had to be rigged so they could be altered for various sequences. My lights were fixed up on cranes, dollies and even on old mike booms, so that I could move them silently during the scene. It was a fantastic sight to see a lamp silently glide in through a window, or even through a hole in the wall, twist and tilt and pan in several directions, then just as mysteriously disappear again. I usually had several electricians running or crawling alongside my camera with 5KW lamps strapped to their shoulders and often they had to wriggle in flat on their tummies — sometimes colliding disastrously — and having done their work wriggle out again before the monster crane mowed them down!

In a bedroom scene, we came through a window (jerked out by wires), followed Michael Wilding toward a four-poster bed, on which Miss Bergman was reclining. This bed was a very strange bed: It had machinery that enabled it to tilt forward about 45 degrees, and we could thus effectively look “down” on her without going high and tilting our Titan blimp. (Miss Bergman performed a remarkable feat in acting and maintaining equipoise on a bed which performed silent see-saws!) All four posts of the bed came away during the scene and we could dolly in to enormous closeups. I had sliding panels cut in some walls to admit lights which disappeared as the camera faced on them. I had men with lamps strapped to them, hiding behind doors: after the camera had passed through, they would creed away. At one time, I had six sets lighted at once. This meant dashing from set to set, checking up till the last moment, and we finished up with three gaffers instead of the usual one. Everyone knows we have a labor problem in England. I leave it to the imagination of the reader when I say that out of the 100-odd electricians, many have been engaged without studio experience — some had never seen a studio before — and those had to work dozens of dimmer shutters, etc., to a split-second cue!

I must say that I owe a tremendous amount to American equipment. I just don’t know what I would have done without American Mazda photospots and photofloods, etc.

Well, it’s over. The film was completed by this method in 12 weeks instead of 25 by usual standards. I could have minimized my difficulties by flat newsreel lighting, but I doubt if any cameraman in the world would have accepted such a compromise, and whatever the results I can only say I tried to obtain the same quality of lighting in spite of the horrifying difficulties. On most occasions, instead of saying: “I want a lamp here,” I had to ask what possible room was left to put a lamp, and how long it could stay there before the camera, or a wall, engulfed it!

Hitch was always ready to change the action if things got really tough, but like anyone else, I was always loathe to admit defeat. I’m not going to weigh the pros and cons of this method of filmmaking. Those against this technique will jubilantly point to the necessity of cutting some of our long reels for story adjustments. I was, of course, chagrined to see the blood, tears and sweat of a reel’s work cut, but it would be invidious to air my views on such a platform subject. I shall only say that it was a technical nightmare I wouldn’t have missed for worlds!

Editor’s Note: When he penned this article, Cardiff was a member of the ASC. In 1949, when Under Capricorn was released, he stepped away from the Society to become a founding member of the British Society of Cinematographers.

If you enjoy retrospective and archival coverage of classic films, you'll find much more here. And for complete access to every issue of American Cinematographer since 1920, subscribe here.