Ring Bearers — The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring

Cinematographer Andrew Lesnie, ACS helps director Peter Jackson bring J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic fantasy novel to the big screen.

Unit photography by Pierre Vinet

In 1954, a strange yet intrepid company of Hobbits, Elves, Dwarves, Men and a tall, intimidating Wizard traversed the Atlantic and set foot on the shores of the United States. The Fellowship of the Ring had arrived. Forty-seven years later, The Fellowship will revisit America, this time on the big screen, in the most anticipated film of this holiday season.

The Fellowship of the Ring is the first installment of director Peter Jackson's three-part adaptation of British author J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. Since its publication in the mid-1950s, the trilogy has sold millions of copies around the world, has been voted “Book of the Century” in countless polls, and has popularized the fantasy genre introduced by Tolkien’s first novel, The Hobbit (1937). Nearly 50 years later, the trilogy continues to influence literature, comics, films, television and computer games, not only by virtue of its ideas and concepts but also by its ability to tell personal stories in extraordinary and epic settings.

The story begins as the hobbit Bilbo Baggins (Ian Holm) leaves his nephew Frodo (Elijah Wood) a ring that has the power to render its wearer invisible. As Frodo soon learns, however, the seemingly innocuous present is much more than it seems. The mysterious and intimidating Wizard Gandalf (Ian McKellen) reveals that the souvenir of Bilbo’s adventures is none other than the One Ring greatly desired by the malevolent Dark Ford Sauron. If the ring falls into Sauron’s possession, his evil shadow will dominate all of Middle-Earth. The only way to avoid this catastrophe is to destroy the ring by casting it into the volcanic fires of Mount Doom, which lies at the heart of Sauron’s dark domain of Mordor. To undertake this dangerous quest, a Fellowship of Nine is formed; traveling with Frodo are fellow hobbits Sam (Sean Astin), Pippin (Billy Boyd) and Merry (Dominic Monaghan), as well as Gandalf, Aragorn (Viggo Mortensen), Legolas the Elf (Orlando Bloom), Boromir (Sean Bean) and Gimli the Dwarf (John Rhys-Davies).

One of the many who read The Fellowship as a teenager was cinematographer Andrew Lesnie, ACS, and he says he had long believed that a true cinematic version of the work “could never be made.” In the late 1970s, Lesnie studied cinematography at the Australian Film, Television and Radio School, during which time he worked with renowned cinematographers Don McAlpine, ASC, ACS; Brian Probyn, BSC, ACS; and Bill Constable, ACS. After a brief stint as a freelance current-affairs cameraman, Lesnie returned to assisting on mainstream productions; he also shot 16mm low-budget short films and music videos. During the 1980s, he regularly photographed second-unit footage for Dean Semler, ASC, ACS.

“I’m a big believer that script and performances are the two main staples of any good film, and on previous films I’d designed the photography to reflect the subtext or internal monologues of the characters.”

Lesnie has twice been named Australia’s Cinematographer of the Year (in 1995 and 1996), and has garnered ACS Golden Tripod awards for his work on Doing Time for Patsy Cline (for which he also received the 1997 Australian Film Institute’s Award for Best Cinematography), Babe, Temptation of a Monk and Spider and Rose. Lesnie’s credits also include Two If by Sea, The Sugar Factory and Babe: Pig in the City.

Although he forged an immediate rapport with Jackson, Lesnie still took a few days to say yes to The Lord of the Rings project. “After all,” he says, “we’re talking about 15 months of principal photography; multiple units shooting simultaneously; huge sets; rugged locations ranging from snowcapped mountaintops accessible only by helicopter to actual swamps; and macro, miniature, aerial, scenic, mountain and water photography — as well as the issue of maintaining one’s physical, emotional and intellectual stamina over a two-year period.”

Any early jitters Lesnie may have felt were quickly allayed, however, by the tremendous amount of preparation that was already well underway. “What I noticed most when I came on board, especially in the wardrobe [designed by Ngila Dickson], the art department and Richard Taylor’s Weta Workshop, was the staggering attention to detail. Peter had been on the project for several years and had very definite ideas about the look of Middle Earth. We agreed that the film should feel like a prehistory of the world, that it should look real. Tolkien takes us into a time 7,000 years ago, when the world was inhabited by Men, Hobbits, Elves, Dwarves, Wizards, Trolls, Ores, Ents, Ringwraiths and Uruk-Hais. The Lord of the Rings takes place at a pivotal time in mythological history, the dawn of the age of man.”

Setting Out on the Long Road

Lesnie immersed himself in the project by rereading the books and going through hundreds of sketches and paintings created by Tolkien artists Ted Nasmith, Alan Lee and John Howe. (Lee and Howe served as conceptual artists for the production.) “The art department was a constant source of inspiration for me,” Lesnie recalls. “In the main hallway was a huge mural that was a condensed visual interpretation of the narrative for the trilogy. It consisted of conceptual drawings, set designs, costume designs, location photos and so forth. It was a matter of throwing everything into one great big pot and letting it simmer.” A big pot it certainly was, for the three films entailed 274 days of principal photography encompassing 600 scenes, 350 sets and more than 4 million feet of exposed negative.

“I’m a big believer that script and performances are the two main staples of any good film, and on previous films I’d designed the photography to reflect the subtext or internal monologues of the characters,” Lesnie continues. “The Lord of the Rings trilogy, however, deals with such a staggering number of issues and takes so many directions that it’s better to let the process operate subliminally. That way, your work starts springing out of a different place than you might normally anticipate.” While Lesnie and Jackson viewed other films for elements such as staging or stylistic treatment, both knew that the books were the obvious source of inspiration. As Lesnie declares, “Tolkien’s writing is exceptionally eloquent in its depiction of feeling and mood.”

Covering the Quest

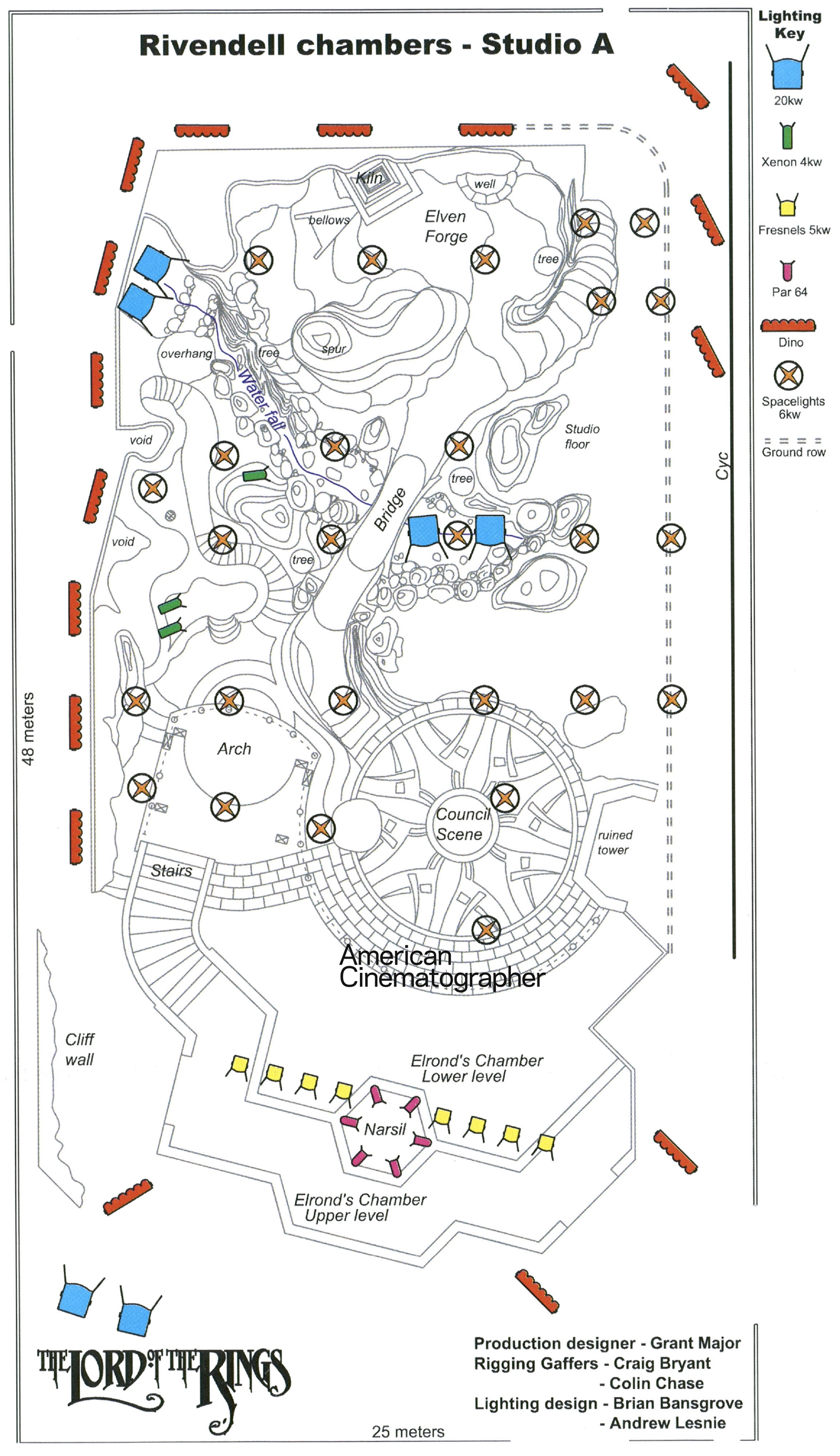

While Lesnie had particular ideas about what he wanted visually, he wanted all of the cinematogra¬ phers involved in the project to be able to make contributions to the shoot. There were sometimes as many as nine units operating on Fellowship, and to communicate with the other cinematographers Lesnie instituted a “Notebook Club” in which each cameraman logged the necessary information from his shoot and then exchanged information. Lesnie recalls that “most of the major sets were pre-rigged from plans designed by chief lighting technician Brian Bansgrove and myself, and all of the cinematographers and gaffers stayed in regular contact. Many mornings I had a phone in one hand and a meter in the other.”

Lesnie describes Jackson’s camera style as “very energetic and fluid. He’s always pushing the envelope. For Peter, the camera is a character, an active participant in the drama. Some directors like to hang back and be more objective, but Peter is like a kid standing at the barricades of a big street parade: he’s just itching to join the show.” Jackson’s propensity for working close to the actors, sometimes at a distance of only 10 inches, necessitated a working aperture of T4 (or higher for shots with critical focus tolerances). “My A-camera focus puller, Colin Deane, is amazing, but Peter’s style was a challenge even for him,” Lesnie says. “We used every multiple-camera technique, such as shooting simultaneous reverses, capturing masters and close-ups at the same time, as well as reaction shots from other characters, and Brian and I always accommodated those situations. Peter comes up with great ideas on the spur of the moment and it’s important to have the systems in place to allow for that spontaneity. It made for some adren¬ aline-charged filmmaking!”

Arri Munich supplied the production with 21 cameras — including Arriflex 535Bs and 435s, Moviecam SLs for the Steadicams, Mitchell cameras for the miniatures department and Arri 35-3 and 2-C units as crash cameras — for the duration of the shoot. The filmmakers employed prime lenses ranging from 10mm to 800mm (a combination of Zeiss Standards and Ultra Primes), along with Cooke and Angenieux 25-250mm HR T3.5 zooms. Canon telephotos handled the longer end of the range, and the production also used macro and Revolution lenses. The equipment was set up by Arri technician Manfred Jahn and maintained by Peter Fleming at Camera Tech Ltd., a Wellington-based company. All three films were shot in the Super 35 format, and Lesnie requested that the ground glasses for each camera have only 2.35:1 aspect ratio frame mark¬ ings and center dots. “It’s a lot cleaner for all concerned to concentrate on one format,” he explains.

Lesnie employed Kodak stocks EXR 50D 5245 and 200T 5293, Vision 500T 5279 and, for visual effects work, S0214. He rated the 79 two-thirds overexposed at 320 ASA, and the 93 one-third stop overexposed at 160 ASA. Lesnie eschewed timed workprints in favor of one-light workprint dailies to avoid any ambiguity about what was going on with the various units’ camera negatives, and the printer lights stayed in the low to mid-30s for the entire production. He chose the EXR stocks because he sought a soft image with decreased contrast. “The light in New Zealand can be quite hard and contrasty. There’s very little pollution and the light has a strong amount of UV in it. However, we were looking for a more ‘European’ sensibility.”

Scaling the Heights

One of the major considerations in bringing Fellowship to the screen was the well-known fact that the average height of a Hobbit is just 3’6". To create this illusion onscreen, Jackson and Lesnie utilized a variety of techniques, such as scale doubles (short or tall stand-ins who doubled for the Hobbits or other characters), scale sets, forced perspective and motion control. The large scale doubles, who were at least 7' tall, were often employed for situa¬ tions involving over-the-shoulder shots looking down at a Hobbit who was talking to a taller character, such as Gandalf or Aragorn; the small scale doubles stood in for the Hobbits during wide shots where the actors’ faces were not visible.

Describing a typical motion-control setup, Lesnie details, “We had to do those types of shots in two parts. First, we shot reference [with a scale double as stand-in] background-plate and clean-plate passes. Then, the actor playing the Hobbit was placed in front of a bluescreen and the motion-control move was scaled up by about 40 percent. We did the bluescreen shots straight away for the benefit of the actors, so they could continue the scene while it was fresh in their minds.

“Historically, forced-perspective shots have been ‘lock-offs.’ Our desire to create in-camera forced perspective for a moving camera prompted Brian Van’t Hul and key grip Harry Harrison to conceive and design a system that utilized differently scaled props moving in a synchronized motion with the camera through the use of motion-control equipment. This process was dubbed ‘Slave Mo-Con’ and allowed two actors to perform live and achieve different scales with a moving camera.”

The sets depicting Bag End offered a somewhat simpler solution to the problem of scale. Production designer Grant Major (who had previously collaborated with Jackson on Heavenly Creatures and The Frighteners) and art director Dan Hennah constructed two identical sets for the interior of the Baggins residence. Each set was constructed with real materials, such as wood paneling and fixed wooden ceilings. One set was built to scale so that the actors playing the Hobbits would appear to be in correct proportion to their surroundings, and the other was constructed on a scale that was 40 percent smaller. In the second set, the actors playing characters larger than Hobbits, such as Gandalf, had to hunch over to avoid hitting the ceiling. The short and tall characters were then filmed in separate sets with matching lighting and camerawork. This solution caused more than a few headaches for the crew — literally. Lesnie reports that the scale set frequently resounded with loud, painful thumps that were invariably followed by some choice cursing.

“We treated Hobbiton as a celebration of a simple life. I used a color scheme with golds and greens, and we scheduled to shoot with as much sunshine as possible.”

Starting at the Shire

From the outset, the filmmakers were determined to stage the adventures of the Fellowship in a fantastic yet believable world. This objective was possibly realized to its fullest extent in the creation of Hobbiton, the serene hometown of Frodo Baggins. The Hobbiton exterior location was not so much built as it was grown. At Matamata on the North Island, a total of 5,000 cubic meters of grass, flowers and vegetable gardens were planted 12 months before shooting began. “We wanted the weather to age Hobbiton naturally,” Major explains.

Lesnie imbued The Shire with an idealized, romantic look. “We treated Hobbiton as a celebration of a simple life,” he says. “I used a color scheme with golds and greens, and we scheduled to shoot with as much sunshine as possible.” Though he added some warmth by using 5293 with an 85B in front of the lens, Lesnie generally eschewed the use of filtration in favor of achieving the desired look in the timing. “Being too aggressive in filtering would have neutralized the greens by pushing the color into the magenta layer,” he notes.

For a night sequence in which Bilbo Baggins has a huge birthday party in an open field, Lesnie recreated firelight and moonlight, a combination that permeates most of the film’s night scenes. “We used flaming torches and gas-bars as actual sources for the firelight where we could, but their usefulness is limited. The best way to artificially reproduce firelight is to have several units pulsing, none with the same pattern; that way, the firelight effect feels more organic. We built firelight rigs that had eight small heads with 3/4 CTO on each, fired into a piece of poly. Four of them were constant to provide general exposure, while the other four all pulsed in random chase patterns. My key lights were 2K, 5K and 10K Fresnels, used either as bounced sources or aimed through frames [ofdiffusion], and all of those lamps were warmed up. For the moonlight effect, we used Muscos and Dinos with Vi CTB.”

Adventures in Bree-Land

In contrast to the idealized world of The Shire, Lesnie wanted to introduce elements of menace and unease into the scenes set in the “frontier town” of Bree. “Bree is a menacing transition point. It’s a fairly aggressive and tough feudal community. At the Inn of The Prancing Pony, we wanted to create a sense of foreboding, so we permeated a very, very slight amount of yellow-green into the grade just to take the look away from a conventional color temperature.”

The sojourn at The Prancing Pony marks the point when the Hobbits realize just how dangerous the Ringwraiths are, after the evil creatures attempt to assassinate the Hobbits as they sleep. Lesnie bathed this dramatic and violent scene in hard blue moonlight. “When the Wraiths enter the room, there are four little beds contrasted with the huge, looming figures drawing swords. The Wraiths’ costumes are black, so only the armor of their gloves and the silver of their swords can be seen in the moonlight.”

Lesnie adopted the same use of contrast for the night exterior shot that shows the Wraiths’ arrival in Bree. “As they ride up the deserted, muddy streets at night, they are black figures passing dark buildings. In such a situation, it’s almost a matter of lighting for black-and-white because you’re attempting to create separation between the elements. I was lighting for shape because we didn’t want to show the Wraiths in too much detail.” The cinematographer maintained this sensibility for all of the scenes featuring the Wraiths. “I used edge and rim lighting. It was more a matter of extracting light from them through the use of cutters and flags. The Wraiths are not a natural occurrence, so they don’t and shouldn’t conform to the natural laws of light or physics.”

Realizing Rivendell

In stark contrast to the lush greens and golds of The Shire and the dark, almost monochromatic Bree, the Elvish realm of Rivendell is rendered in autumnal colors. “The word for Rivendell was indeed autumn,” Lesnie states. “On one level, that was the physical atmosphere that we wanted to invoke, but Rivendell also reflects the decay of the Elvish empire. While Rivendell was designed by the Elves to be at one with nature, it is a place where the Elves have really let nature take over. In short, the Elves’ days in Middle-Earth are numbered.”

Once again, a good portion of this effect was achieved via Major’s production design, which features floral designs and leaf patterns in the woodwork, as well as hand-carved door frames, pillars and statues. The principal sets built for the Rivendell scenes were the chambers of Elrond (Hugo Weaving), the Council Circle, a forest complete with a bridge, a waterfall and an Elvish forge. The lavish set was well-utilized, with a large number of daytime, night, twilight, interior and exterior sequences staged to fully exploit Major’s work. In addition, a Rivendell exterior set was built in a nature preserve, taking full advantage of the surrounding natural forest.

To cover the variety of scenes and the looks they required, Lesnie hung a vast array of space lights, Dinos and Xenons from the grid built into the set’s ceiling, and ringed the set on the ground with 20Ks. He wanted to establish a soft ambience punctuated by shafts of light, a strategy that was applied to both the day and night scenes. “The major scene that takes place on this set is the Council scene, in which The Fellowship is forged. The sequence was treated as a very warm autumn afternoon with the feeling of the soft sun coming through the trees and hitting the Council area. Of all the scenes set at Rivendell, this one had the least contrast; the sunlight breaking through the trees was half to a stop over the ambient light, while the fill was a stop and a half under.”

For the night scenes, Lesnie kept the ambience moody through his use of contrast and color. “There are two night scenes that follow each other. The first is between Aragorn and Boromir, who are later joined by the Elven princess Arwen [LivTyler]. For that scene I had some lavenderblue ambient light and a 20K creat¬ ing a shaft of blue moonlight that penetrated the whole set.” For a nighttime encounter between Aragorn and Arwen, Lesnie used the Xenons to establish shafts of moonlight breaking through the forest canopy, accentuating them with subtle use of smoke. “For that sequence I decided to apply a more ‘classical’ blue, which is a bit kinder on skin tones. When you use lilac and lavenders, the actors’ skin tones can sometimes veer too much toward magenta. I lit that scene for beauty, because it’s one of the rare moments where Aragorn reveals his true feelings to the woman he loves. I’ve always equated the blue end of the spectrum with the concept of truth.”

For a sequence involving Gandalf and Elrond, Lesnie utilized a series of lavender, lilac and salmon gels to create a suitable twilight feel. Lesnie also added some diffusion during digital timing to provide Rivendell with a delicate glow befitting an Elvish kingdom. “I put the diffusion in during the grading, because there are so many effects shots throughout the Rivendell sequences that I thought it better to wait until I could see the entire sequence. During the digital-grading process, you can use the software to emulate different types of diffusion filters. We treated ours as a Tiffen Pro-Mist, softening the highlights but not the blacks.”

Down in the Depths

Perhaps the most dramatic sequences in The Fellowship of the Ring take place in the all-butdeserted Mines of Moria. The mines once resounded with the clamor of Dwarvish miners, but the miners dug too deep into the earth and unwittingly unleashed dark and evil forces. The mines are now a place of death and decay, inhabited by hordes of ferocious Ores and Trolls. “We made the decision early on that the Mines of Moria would be desaturated, a look we achieved in the grading,” Lesnie comments.

Unlike the fire- and moonlight of the previous scenes, there was no natural light source in the underground mines. Lesnie employed an underexposed base ambience, with soft sources adding texture to the environment. “The walls of the chambers were dark and gray stone, yet they were very textured. To bring this out, we used big, directional lamps as a soft toplight or a long, raking sidelight. The only sources of light for the Fellowship’s passage through the mines were Aragorn’s flaming torch and Gandalf’s magical staff. We had several versions of the staff; one was electric with a bulb and cable and another was battery-powered. The light increases and decreases depending on Gandalf’s temperament or his desire to see more. We used the staff as the justification for creating a continuous pool of light around the Fellowship, and the illumination was created by fading Fresnel units up or down and by using Chinese lanterns on boom poles.”

“We recreated that using a 4K Xenon with a bit of smoke to accentuate the shaft. That was the principal light source in the room.”

For a brief and poignant scene at the tomb of Balin, Lesnie borrowed from the conceptual artwork of Alan Lee. “Alan had painted a strong and dramatic shaft of light falling onto the tomb itself. We recreated that using a 4K Xenon with a bit of smoke to accentuate the shaft. That was the principal light source in the room. I used it as a backlight, bouncing it back into the actors’ faces for fill.”

For the thrilling confrontation between Gandalf and a flying, firebreathing monster known as a Balrog, Lesnie again replicated firelight, but this time on a much more dynamic scale. The fight takes place on a thin stone bridge over a huge fissure in the rock floor. Molten rock boils and spits deep within the fissure. “There was a lot of kinetic lighting in that sequence,” Lesnie says. “We did close-ups of Ian McKellen where he was surrounded by so many units that I lost count of how many lighting cues there were. We needed to show the growing light of the Balrog as it towered over Gandalf, the sparking interaction between Gandalf and the Balrog’s swords, and the lightning strike that occurs when Gandalf drives his staff into the bridge, shattering it. Poor Ian was confronted by a complete armada of modern lighting technology. It must have been like a disco for him!”

Much of the mine environment consisted of sets rendered both in miniature and full size, but the largest chambers were created digitally. Lesnie says that the opportunity to create “digital lighting” excited him. “There were no natural sources of light, so we had to introduce lighting concepts to illustrate depth. We rim-lit the pillars to get perspective, because we wanted to show the audience the past grandeur of the Dwarf civilization.

Luminescent Lothlorien

The glow and glimmer of Lothlorien, the realm of the High Elves, could hardly have been in greater contrast to the dank melancholy of Moria. There are essentially two parts to the Lothlorien sequences — the forest on the outskirts and realm itself — and each had a slightly different appearance. “In the forest, which was an actual location, the ground and trees are covered in moss,” Lesnie explains. “We wanted a very warm, late-afternoon look, something just before twilight, so we placed ungelled Dinos with spot bulbs down one side of the forest and gunned them through the trees. It was a gorgeous look, and we were able to work this scenario whether the sun was in or out. The light was just clipping the trees, providing highlights rather than frontal lighting; that lent the trees orange edges, which worked really well.

“In Lothlorien itself, everything is slightly cooler and lavender to impart an ethereal feel. This color has a fragile quality to it because Lothlorien is a cerebral, thinking world. We used the same kind of diffusion we’d used at Rivendell in order to connect the Elvish realms. Once again, I used space lights to get an ambient exposure, and I also raked the forest with Xenon lamps to get a low, warm sidelight.” Lesnie enhanced the ethereal effect with twinkling lights, an effect he achieved by aiming lights through layers offoliage and then moving the foliage, as well as placing small units in the background of the shots so they would appear in soft focus against the darkness.

To achieve a glowing, luminescent quality for the Elvish Queen Galadriel (Cate Blanchett), Lesnie used soft light exposed at key. Lesnie also extended Jackson's predilection for eye lights. “Peter likes to see eyelights, and to create that effect we usually used ‘wands,’ which were two 2-foot Kino Flo tubes taped together. In close quarters, these wands are ideal and virtually instantaneous tools; they have four inten¬ sity levels, they’re cool and very flexible, and they’re perfect for handholding. For the character of Galadriel, however, I wanted to create a special eyelight, because Tolkien describes her by saying ‘no sign of age was upon her, unless it were in the depths of her eyes; for these were keen as lances in the starlight and yet profound, the wells of deep memory.’ In order to achieve that quality, we created the ‘Galadrilight,’ which was simply a rig of hundreds of Christmas tree lights mounted next to the camera. This technique placed many reflections in Cate’s eyes, creating a wonderful otherworldliness. Her skin is so luminescent that sometimes I didn’t have to use any fill, because the Galadrilight was doing the work.”

It’s All in the Timing

Digital timing was as an integral part of the filmmakers’ plan from the outset. “It was always a critical part of the film’s fabric,” Lesnie confirms. “With this kind of technology, there’s a legitimate fear that the cinematographer will be cut out of the creative process once a production moves into post. However, thanks to the support of Peter and his co-producer, Barrie M. Osborne, I had the opportunity to ‘close the loop’ in terms of delivering a negative with the imagery that Peter and I had in mind from the beginning.”

The digital-timing facility was purpose-built by Peter Doyle and PostHouse AG, a digital grading and visual-effects house based in Germany. The software, provided by the Hungarian company ColorFront, was custom-designed for the project; it has since been further developed and launched on the general market as 5D Colossus. Doyle has previously timed sequences in films such as Dark City and The Matrix. Lesnie says Doyle’s “intimate knowledge of film stocks and labs, as well as his aesthetic sensibilities, made him ideal for this project.”

The digital timing gave Lesnie the opportunity to delve into fragile parts of the color spectrum, such as the lavender-blues in the Lothlorien scenes, the blue-greens used in the Weathertop sequences and the magenta-salmons in Rivendell. “I wanted to see how this technology would allow me to create a series of unique looks for the film’s diverse settings. What I enjoy about the digital system is that part of the keyboard is solely devoted to primary and secondary colors, much like a Hazeltine or Colormaster, with RGB/CYM numbers registering every change and the punch of a button serving as the equivalent to one trim at the lab.”With Jackson and Osborne’s support, Lesnie was able to ensure that the production’s laboratory, The Film Unit, and head timer Lyn Seaman remained an integral part of the digital-timing process.

The release prints are on standard Fuji print stock, because Lesnie believes that “the combination of Kodak negative and Fuji print stock has a slightly softer quality. To achieve the desired effect, we did tests taking the prints right through the process with The Film Unit and Deluxe in Los Angeles.”

Lesnie sums up his work on the project by saying, “This film has been a huge learning curve for me. From the conceptual lighting at Weta Digital to sitting in with composer Howard Shore while he conducted the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, I have been privileged to take part in a project that involved up to 2,500 passionate and dedicated people. Working with Peter was a very enjoyable experience; he has a commitment to strong performances and runs an energetic and goodhumored set. I was constantly amazed at his ability to keep a solid focus on so many aspects of the project at any one time. The story of honest people who, through the power of loyal friendship and individual courage, find the resolve to take on the forces of darkness is very much a relevant tale in the modern age.”

You'll find our coverage with Lesnie on the Rings followups The Two Towers here and Return of the King here.

The cinematographer died at the age of 59 on April 27, 2015, after a brief illness. You'll find our complete In Memoriam remembrance here.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.

Access the every issue of AC and every story from more than the last 100 years with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.