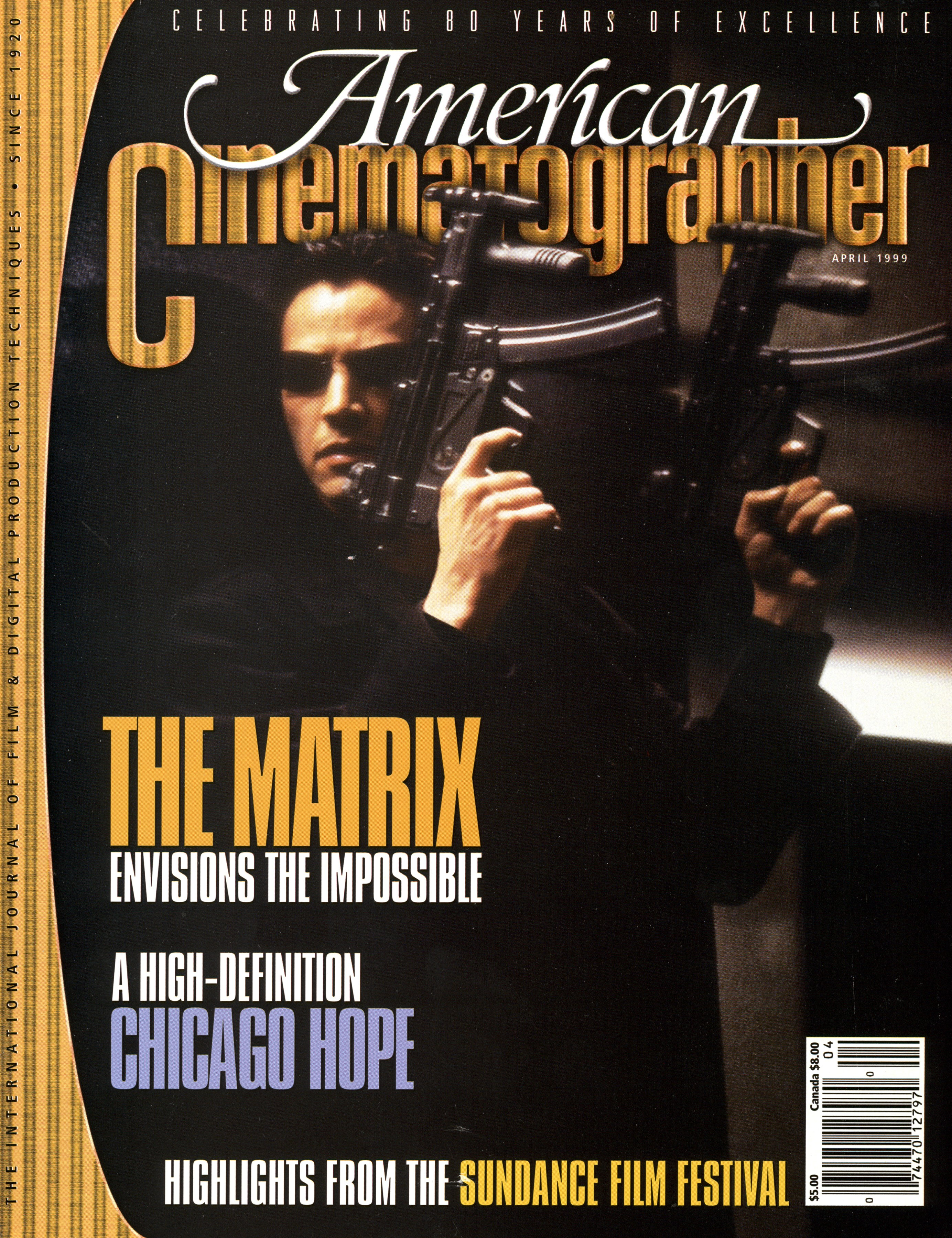

The Matrix: Welcome to the Machine

Directors Lana and Lilly Wachowski reteam with cinematographer Bill Pope on this futuristic, eye-popping action thriller.

Unit photography by Jason Boland, courtesy of Warner Bros.

Computerized gadgetry has assumed such an increasingly pervasive role in our everyday lives — from microprocessor-controlled automobiles to hyperspeed Internet e-mail and cell phones — that one might wonder if the tail is wagging the dog. With the impending end of the millennium inducing waves of paranoia and Y2K computer-crash hysteria, it's not surprising that technophobic films such as Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and James Cameron’s The Terminator (1984) seem ever-more accurate in their depictions of microchips run amok.

The Matrix, a new film from sibling filmmakers Lana and Lilly Wachowski, offers an even more grim vision of the future. Born in Chicago in the mid-1960s, the Wachowskis grew up on a healthy diet of comic books, Japanese animation and films of all kinds. While working at construction jobs, they began to write comics and screenplays that combined the seemingly dissimilar aesthetics of their favorite mediums. Before making their directorial debut in 1997 with the dark and stylish heist thriller Bound (which they also co-wrote), the duo had already penned the script for The Matrix.

“Our main goal with The Matrix was to make an intellectual action movie,” Lana explains. “We like action movies, guns and kung fu, but we're tired of assembly-line action movies that are devoid of any intellectual content. We were determined to put as many ideas into the movie as we could, and purposefully set out to try to put images up on the screen that people haven’t ever seen before.”

Out of the Void

For years, the script for The Matrix languished in limbo because many in Hollywood couldn't grasp the tale’s highly complex narrative and extravagant visual elements. “Hardly anybody in town even understood it,” says Lana. “It became almost a running joke. People thought it was too complicated and too dense.”

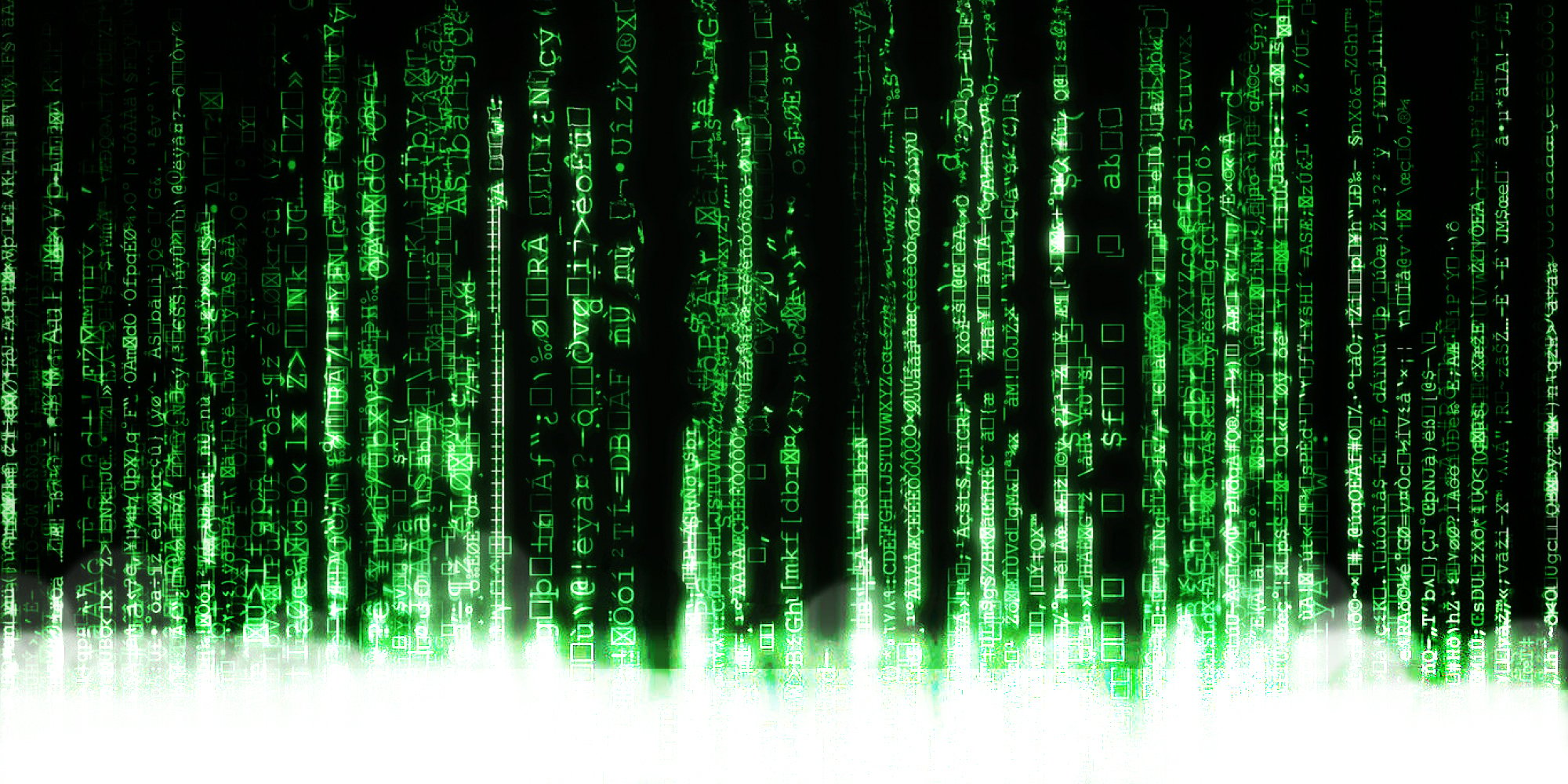

“The premise for The Matrix began with the idea that everything in our world, every single fiber of reality, is actually a simulation created in a digital universe,” he explains. “Once you start dealing [narratively] with an electronic reality, you can really push the boundaries of what may be humanly and visually possible.”

To help distill this concept into a more readily understandable form, the Wachowskis hired several comic-book craftsmen, including popular Hard Boiled artist Geof Darrow, to hand-draw the entire film as a highly graphic storyboard bible. “We don't really like the way conventional storyboards are done,” Lana reveals. “Instead, we brought in some friends of ours to draw out every single action beat, visual moment and stylistic shot in the film. Then, for months, we pored over every frame, exploring how to attack each shot. This also allowed us to be very specific, in terms of the budgeting and visual-effects requirements.”

This graphic representation of the film also became an invaluable tool for director of photography Bill Pope, whose common interest in comic books had previously landed him the director of photography assignment on the Wachowskis' Bound. Pope recalls, "They had seen and loved [the 1993 horror-fantasy film] Army of Darkness, which I shot for director Sam Raimi. They called me in, and we had a terrific meeting. I think they hired me because I read comics and knew what they were talking about whenever they mentioned a particular title. In fact, during our meeting, there was a copy of Frank Miller's Sin City on their desk, so I asked, 'Is that what you want the film to look like?' We were all impressed by Miller's use of high-contrast, jet-black areas in the frame to focus the eye, and his extreme stylization of reality. I had long wanted to do something that stylized on film."

Not incidentally, "stylization" formed the basis of Pope's early career. A 1977 graduate of New York University's film program, the cameraman recalls, "Film school was pretty intense back then, because there were only a few of us who concentrated on cinematography. Everyone else wanted to direct. In my class, it was just Ken Kelsch [ASC] and myself, and in the class behind us there was only [director and former cameraman] Barry Sonnenfeld. The three of us shot everybody else's films. After graduating, I shot a few of those early videos that were shown only on closed-circuit TVs in clubs. When MTV came along in the early 1980s, and everybody began making videos, people said, 'Get Bill Pope, he's shot these things!' Suddenly, I was a director of photography."

Pope would spend the rest of the decade photographing several hundred videos. Along the way, he earned an MTV Award for Best Cinematography for his black-and-white camerawork on the Sting clip "We'll Be Together Tonight."

He then segued into commercials and features. "In 1989, Sam Raimi gave me the chance to shoot [the sci-fi fantasy] Darkman," Pope remembers. "I only got the job because Barry Sonnenfeld told Sam to hire me. Fortunately, Sam just said, 'You're hired, let's go!' Otherwise, I never would have gotten a feature. For a long time, music videos were considered the illegitimate children of the filmmaking industry. It wasn't until the late Eighties and early Nineties that music-video cinematographers were even considered legitimate enough to shoot commercials. After I shot Darkman, though, I was able to concentrate on shooting movies and commercials." Pope's other feature credits include The Zero Effect, Gridlock'd, Clueless and Fire in the Sky. Additionally, he shot the pilot for the television series Maximum Bob, which was directed by Sonnenfeld.

Technology Takes Over

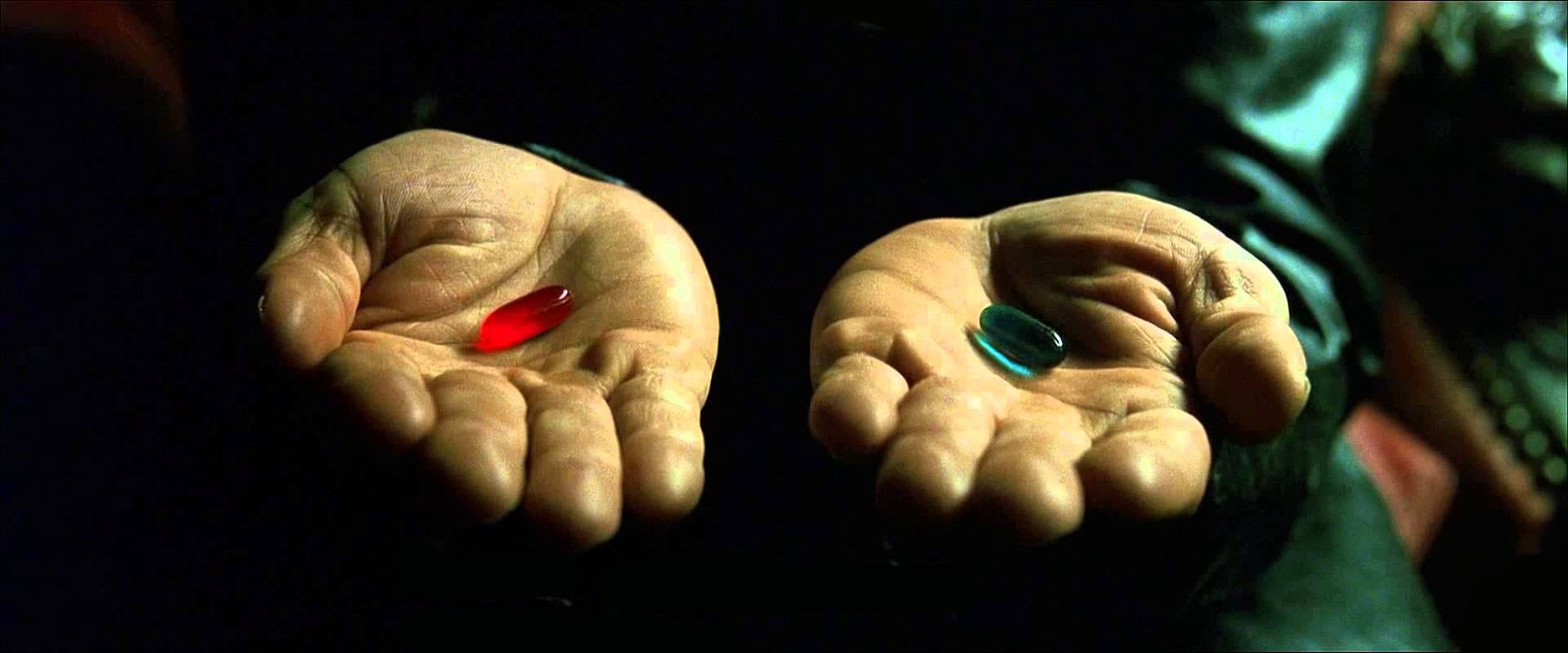

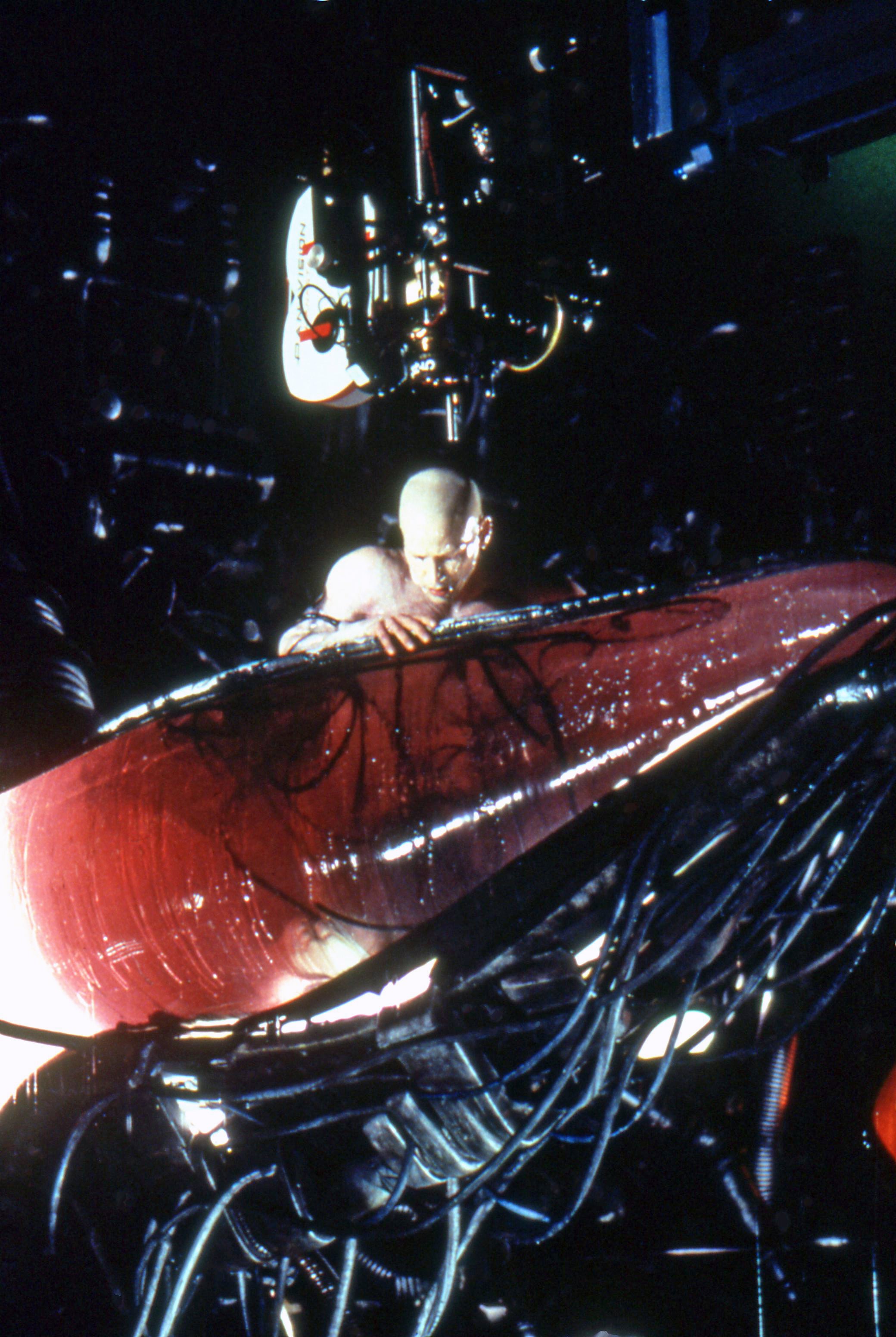

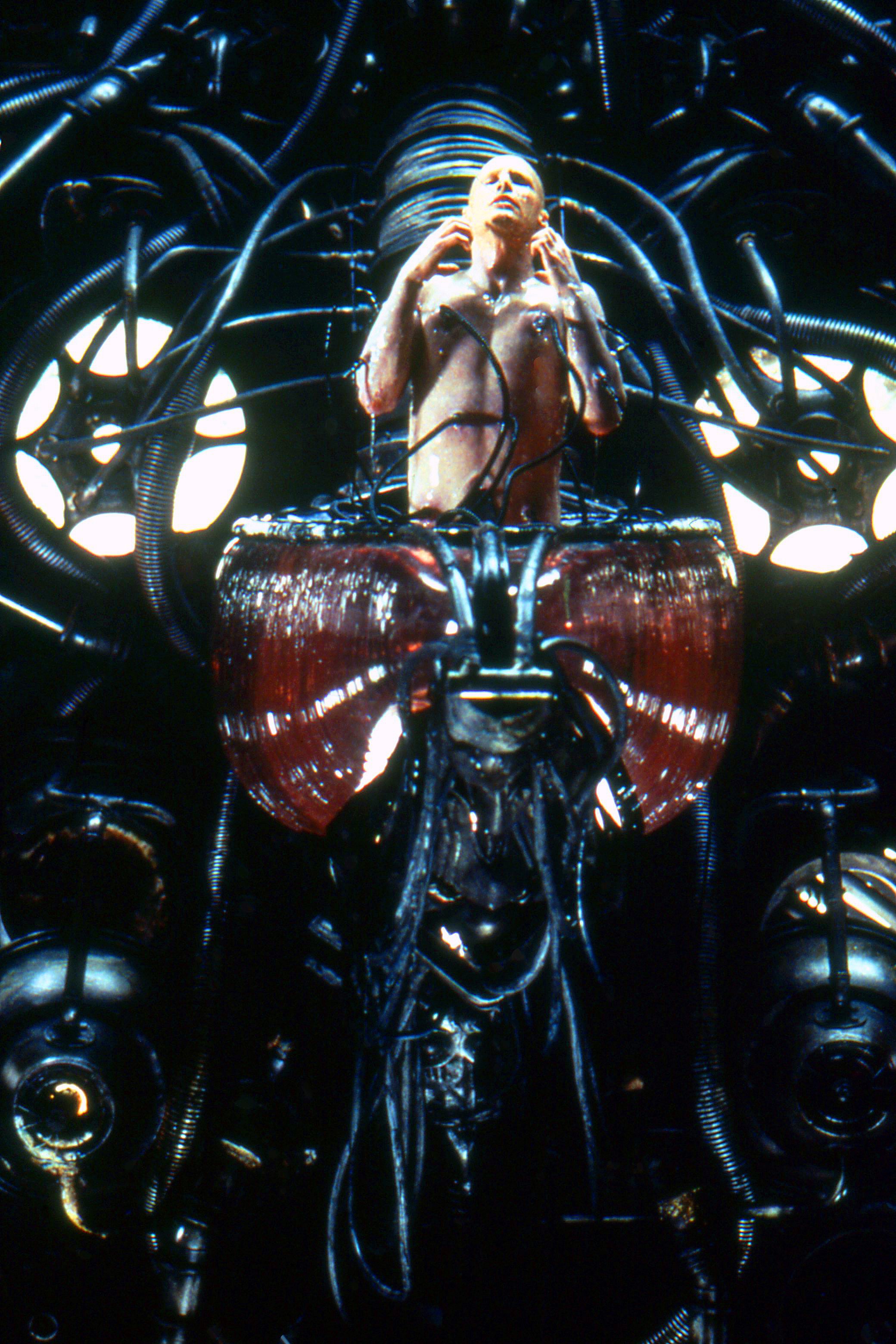

The story concept that propels The Matrix is intricate: the year is 2197, and human reality is merely a computer-simulated environment. "At some point in the past, artificial intelligence took over the world," Pope relates. "In an effort to regain control, humans blacked out the sun, because the computers were running off of solar power. But the machines outsmarted us and took over our bodies, placing them in pods and using them as batteries — drawing off the BTUs we produce. While we float in a liquid, they project into our brains the world we think we live in, which is called the Matrix. Everything we do in our lives, every day, is only a computer simulation of reality.

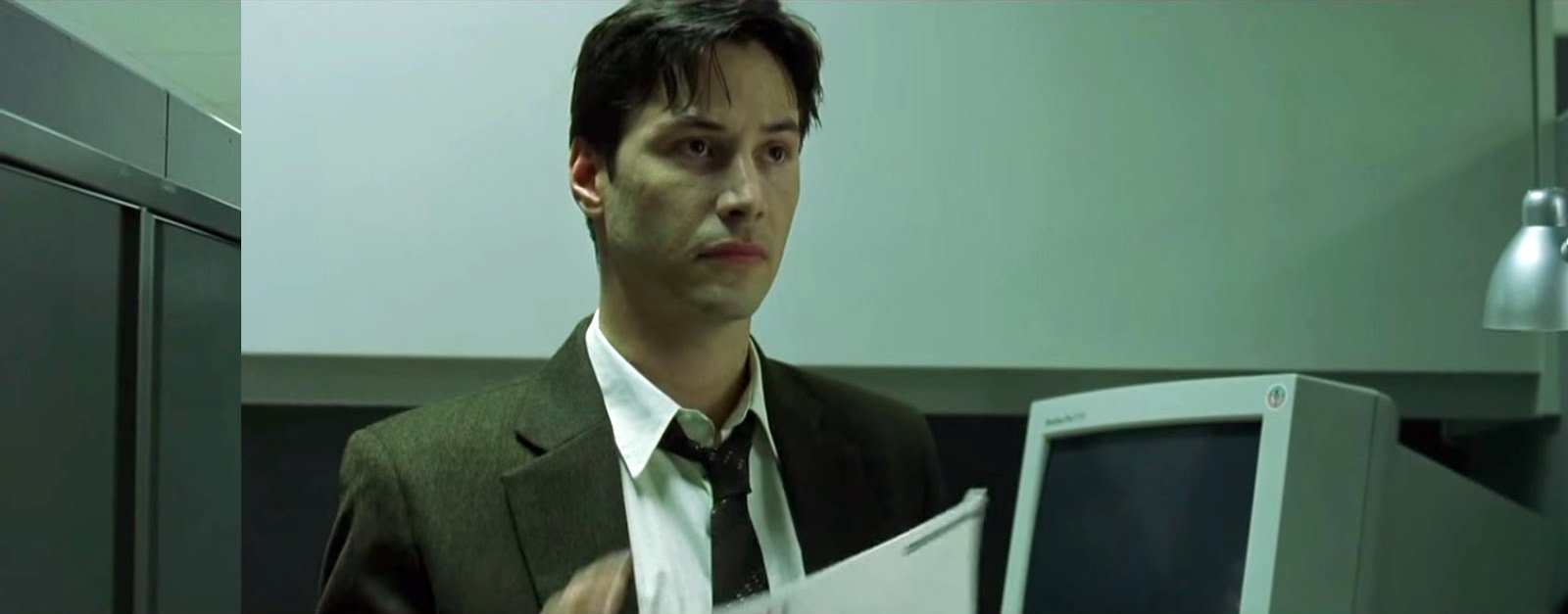

"Certain individuals have figured this out, however, and are waging a battle against the computers. These rebels fight within the Matrix against Agents who are themselves computer programs. The Agents can do anything, become anybody and change any natural law, but the humans can't. One of the main protagonists, Morpheus [Laurence Fishburne], is looking for an individual who reportedly can do what the computers can: walk through the Matrix and change reality. Morpheus believes that this individual is Neo [Keanu Reeves].

"It's a pretty complicated Christ-story," Pope admits, "but for the Wachowskis and myself, one of the best kinds of comic books is the 'origin' story, which outlines the beginnings of a superhero like Daredevil or Spiderman. The Matrix is the origin story of Neo."

Adds Lana Wachowski, "We wanted the film to be a journey of consciousness. The main character that takes the audience on this journey is Neo, who initially knows only as much about the movie's world as the audience. We soon discover, however, that the characters in the film can instantaneously have information downloaded into their heads; Neo can, for example, suddenly become a kung fu master like Jackie Chan!

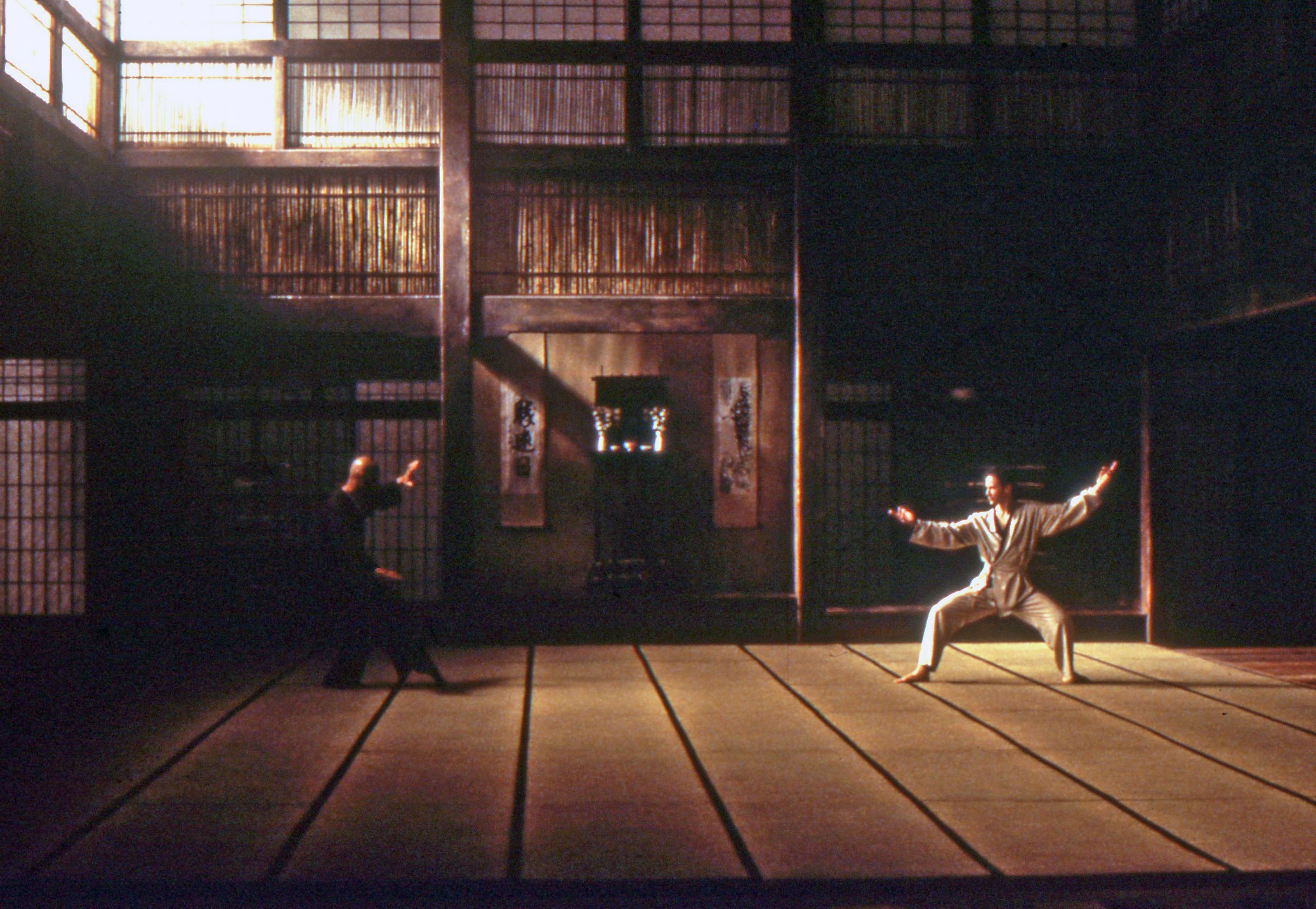

"Lilly and I love Hong Kong action films, and we both feel that they're miles ahead of American action films in terms of the kind of excitement that the action brings to the story. American filmmakers have gotten to the point where they create their fights in the editing room. Those types of sequences are just designed for a visceral, flash-cut impact, and the audience's brains are never really engaged. There's a bunch of quick cuts — bam! bam! bam! — and then it's over; the fighting never involves the audience on a story level. Hong Kong action directors actually bring narrative arcs into the fights, and tell a little story within the fighting."

A Ballet of Violence

With this Eastern aesthetic in mind, the Wachowskis hired renowned Hong Kong director/stunt choreographer Yuen Wo Ping to coordinate all of the elaborate fight sequences in The Matrix, and also to serve as the personal martial-arts trainer for the four principal cast members. "In order to pull off these very elaborate fight scenes," states Lana, "we had to take four Western actors and teach them kung fu for four months before we started shooting. In Hong Kong, Wo Ping usually directs his action scenes and picks all of the camera angles. For our fights, we talked to him about what the actual storyline of the fight was, and he would then go off and choreograph it. Once he had the whole 'dance' of the fight, we'd ask what he would recommend for every shot. We'd then add whatever flourishes, camera moves or other angles we wanted on top of that."

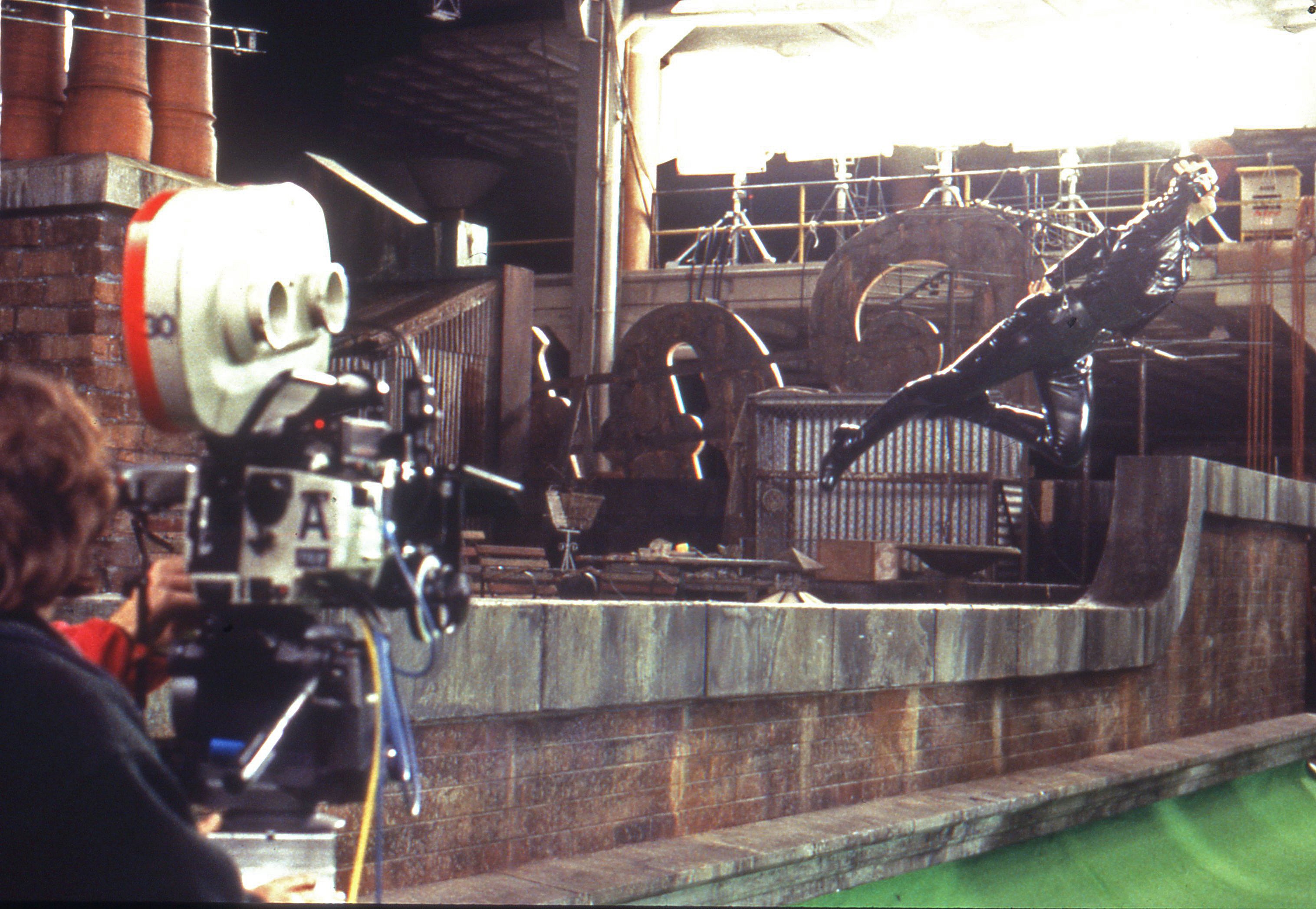

An integral part of Wo Ping's fight choreography is his legendary use of wire-harness stuntwork. Truly an awe-inspiring feat of visual trickery, the technique allows actors to seemingly defy the laws of physics as they leap, fly and twirl around their opponents in battle. "Wo Ping's wire-work is the best," Lana attests. "Using the wire system, you can improvise very easily. They can put a wire anywhere and hook somebody up to it at any moment. They don't need a big rig — just a bunch of guys who grab hold of it and say, 'Let's go!' It's very fast, fluid and safe. In Hong Kong kung fu films, they basically put people on wires for everything, from jumping to standing up or even running. It makes all of the movement look very graceful and kind of surreal. We thought that was perfect for The Matrix.

"We also tried to detail the action in a way that isn't really done in Hollywood anymore," Lana continues. "There are many incredible and beautiful images in violence, and I think violence can be a great storytelling tool. [Filmmakers] have come up with an incredible language for violence. For example, what John Woo [The Killer, Face/Off] does with his sort of hyper-violence is brilliant. He pushes violent imagery to another level. We tried to do that with The Matrix as well. "

Imagining the Future

With the complex requirements of the film's serpentine narrative and the grandiose environments and events the Wachowskis had envisioned, the producers decided to shoot the entire film in Sydney, Australia. Utilizing virtually every stage in the city — including all of Fox's stages at their new studio facility, as well as several converted warehouses — the production quickly became a formidable presence. Among the hundreds of Australian crewmembers on the show were production designer Owen Paterson, costume designer Kym Barrett, gaffer Reg Garside, rigging gaffer Craig Bryant, key grip Ray Brown, camera operator David Williamson, focus-pullers David Elmes and Adrien Seffrrin, clapper/loader Jason Binnie and loader Jodi Smith, as well as second-unit director of photography Ross Emery and underwater cameraman Roger Buckingham, ACS.

"My prep for The Matrix consisted of two months of scheduling and rescheduling," Pope recounts. "The Wachowskis were swamped with many concerns because of the film's level of complexity. Everything had to be preconceived and explained. Lana and Lilly are naturally reticent people, so that was hard for them. They usually don't want to tell you anything unless they're forced to. During my prep for Bound, for instance, I asked them to sit down with me and go through each scene. In the beginning, they'd try to shrug off my questions by saying things like, 'Well the scene is just two guys sitting there talking.' Then I'd ask how they planned on covering it. They'd say, 'Oh, conventionally.‘ I'd then have to say, ‘Okay, let’s backtrack — what's the first shot?' Finally, they'd say, ‘Well, we’ll start on one guy’s boot, go up his body, end up on his face in extreme close-up and then whip-pan over to the other person.' Now we laugh whenever we say ‘conventional’ coverage. Ultimately, we went through all of Bound shot by shot. On The Matrix, however, the sisters were so busy during prep that that type of meeting never happened."

Because the entire film was meticulously storyboarded in color, though, Pope did have an understanding of the visual style that the directors wanted to create. "Lana and Lilly wanted The Matrix to have two distinct worlds," says the cinematographer. "There is the world in the 2197 future — in which we have the pods made by the computers — and then there’s the present-day Matrix world, which was designed to be a slightly unappealing reality.

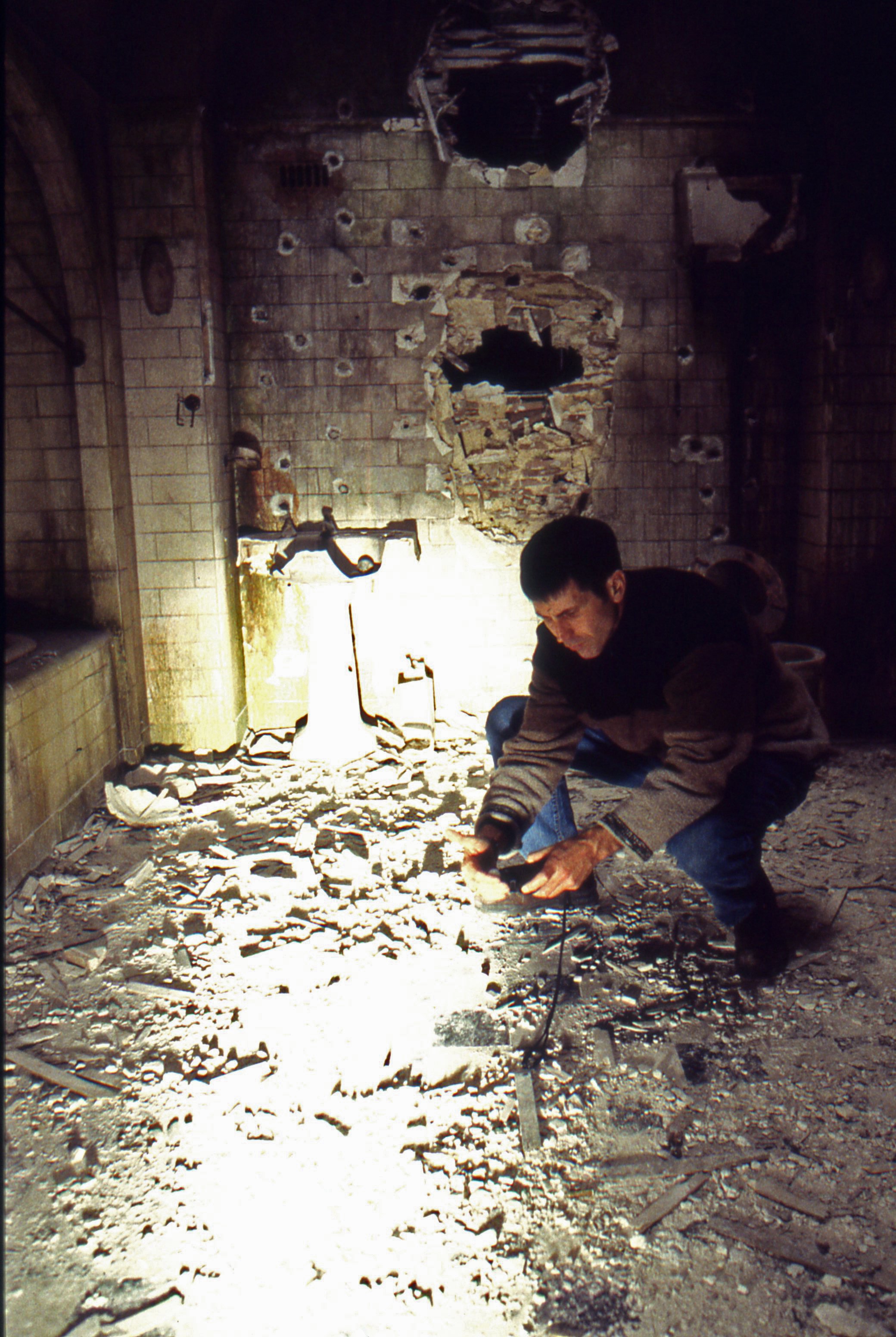

“The future world is cold, dark and riddled with lightning, so we left the lighting a bit bluer and made it dark as hell. Also, the future reality is very grimy because there's no reason to clean it — only the pods need to be sterile. Because humans haven’t actually manufactured anything for a hundred years, anything that had been manufactured is now old and rusty.

“We didn't necessarily want the Matrix world to resemble our present world,” adds Pope. "We didn't want any cheery blue skies. In Australia, the sky is a brilliant blue virtually all the time, but we wanted bald, white skies. All of our TransLight backings [for the stage work] were altered to have white skies, and on actual exterior shots in which we see a lot of sky, we digitally enhanced the skies to make them white. Additionally, since we wanted the Matrix reality to be unappealing, we asked ourselves, 'What is the most unappealing color?' I think we all agreed on green, so for those scenes, we sometimes used green filters, and I'd add a little bit of green in the color timing."

Pope photographed The Matrix using Panavision Platinum cameras and Primo prime lenses, which he brought with him from Woodland Hills, California. (At the time of production, Samuelson Film Services in Sydney had only recently been acquired by Panavision, and couldn’t meet the film's demands.) The cinematographer shot in the Super 35 2.35:1 aspect ratio, utilizing Kodak's Vision 500T 5279 and 200T 5274 stocks. “We shot all of the day exteriors and effects shots on 5274, and used 5279 for all the interiors. I like the look of 79, and I like to see a little grain. I shot in Super 35 partially because I had too many cameras to come up with enough anamorphic lenses, and also because of the sheer size of the sets. I felt that I might have had a little trouble lighting the sets to get the stop we'd need for anamorphic. Regardless, I do like Super 35; I also shot Fire in the Sky in that format.”

An additional critical factor in the film's lighting approach was dictated by a special photographic technique that the Wachowskis were determined to integrate into the filming. This approach was inspired by Neo's newfound mastery of virtual time and space. Explains Lana, "We wanted to shoot much of the action in super-slow-motion — up to 300 fps. For certain shots, we wanted to shoot high-speed while keeping the apparent movement of the camera at regular speed, which is basically impossible. In preproduction, we looked into the idea of a rocket camera, which we were going to shoot across the set at something like 100 mph while filming at 150 fps, but [visual effects supervisor] John Gaeta came up with a different process that became the basis for these sequences."

(This extreme slow-mo photography, dubbed "Bullet Time" by the Wachowskis, is detailed in the accompanying visual effects story also in this issue.)

Lighting for Speed

“The sets for The Matrix were immense — the biggest I personally have ever seen," says Pope. "We had two camera units working all the time. The first unit shot for 118 days, and the second unit shot for 90. The first 40 days were spent shooting on rooftops in downtown Sydney, where, because of safety issues, we really couldn't put up elaborate lighting or anything that flew. There, I basically used some negative fill, and that was about it — which was fine, because I like to work in a naturalistic way. In general, we'd use lights only for matching purposes, because the weather in Sydney changes rapidly and often."

Australian gaffer Reg Garside expands, "These exteriors were all about logistical problems. We were shooting in the middle of Sydney, which is where all of the city's work gets done. We had to crane generators halfway up the sides of buildings, because we needed 200 or 300 amps of phase power on some of the rooftops. Not only did we have to cater to the lighting, but we also had to provide power for the special effects people, who had these big smoke machines as well."

Moving indoors, Pope and Garside confronted the massive undertaking of lighting the immense sets to allow for the Wachowski's desired 300 fps frame rate for extreme slow-motion shots. Notes Garside, "The high-speed lighting requirements were a big concern, because on the big sets — such as the subway and the government building exterior and lobby — we needed a massive amount of light to be able to shoot between Bill's T2.8 base and the T16 needed for high-speed filming. On some stages, in fact, we had to rig more than 1,000 Par cans in the permanents [to produce the needed levels of light]. I used Par cans a lot, because I could easily control the ambience from T2.8 to T16 just by turning additional units on and off. Also, Par cans are much cheaper than Maxi-Brutes, and although they use the same sort of bulb [a Par 64], I've found that I can rig them in much more weird or difficult places than I can put a Maxi. Having 1,000 Par cans is actually like having 80 Maxis, but we don't even have 80 Maxi-Brutes in Australia!

"For speed and maximum control," Garside continues, "every single light ran through a dimmer rack, so if Bill told me to give him a T8, I could give him a T8 by adjusting a lever on the controls. For a T2.8, you may only use one lamp, but for a T16, you may need 32 lamps. You're really dealing with an exponential doubling-up effect to get the extra stops. Bill actually used a lot of overhead lights through light gridcloth diffusion to create an ambience. So I had [rigging gaffer] Craig Bryant pre-rig Par cans in the roof for an ambience that could get me up to a T16. We then had to build a lot of custom overhead cloths, which we call sails, and virtually hand-fit them into position on the sets."

Pope elaborates, "We shot most of this movie with tungsten lights. Also, by using Par cans, we could change the light level without changing the color temperature, simply by turning units on or off. However, I do like to use Kino Flos on faces for interiors. In fact, I prefer to have Kinos around the actors, because they're a lot cooler. We used truckloads of Wall-O-Lites and 4' by 4' Kinos on this film."

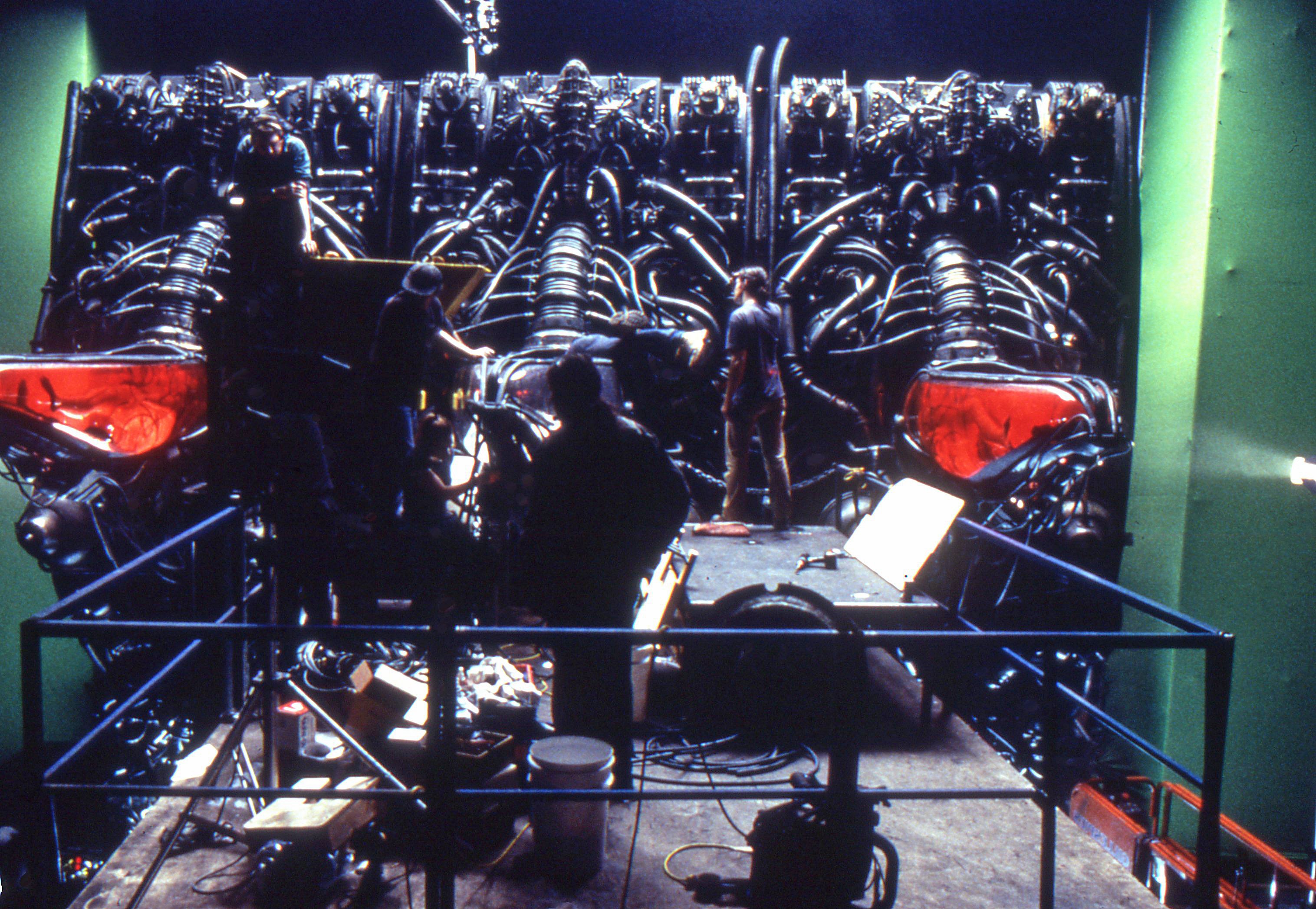

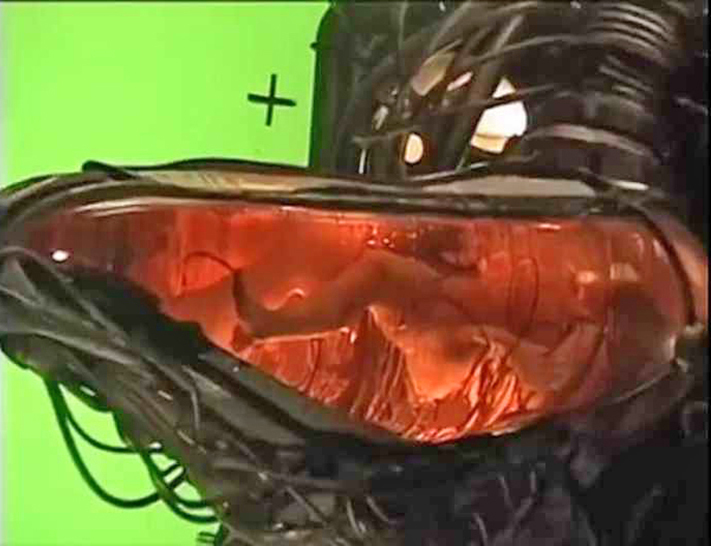

Harvesting Humanity

For a key set depicting the future reality of mankind, production designer Owen Paterson (The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert; Welcome to Woop-Woop) constructed several of the incubation pods in which humans are held in stasis while their energy is tapped by the computers. "We had about six of these liquid-filled pods," Pope describes. "Each was just large enough for a human being, and jutted out of a 30' by 60' wall that Owen built. Each pod was about 15' off the ground, which necessitated the building of numerous working platforms for the cast and crew. We stayed with the cooler light — 1/4 CTB on the tungsten lights — and once again used a big soft toplight, about 200 Par cans coming through light gridcloth. We also had Kino Flos coming up from below [to suggest an infinite number of the pods above and below the six practical props]. We also had Lightning Strikes units popping off occasionally, because there is supposed to be a lot of static electricity in the future reality. Additionally, Reggie, Owen and I worked hard to build some Kinos and MR-16s into the pods themselves."

"Lighting the pods was pretty tricky, because they were full of this red, liquid goop," Garside elaborates. "We wanted to make them glow, so we used underwater-safe Kino Flo units from Hydroflex, which we built into the base of each pod. That technique worked really well for wide shots. When we got in closer, we used the same interior lighting, but since the pods were made of a clear Perspex material, we enhanced their lighting by shining 1K babies up from below."

The Rebels' Lair

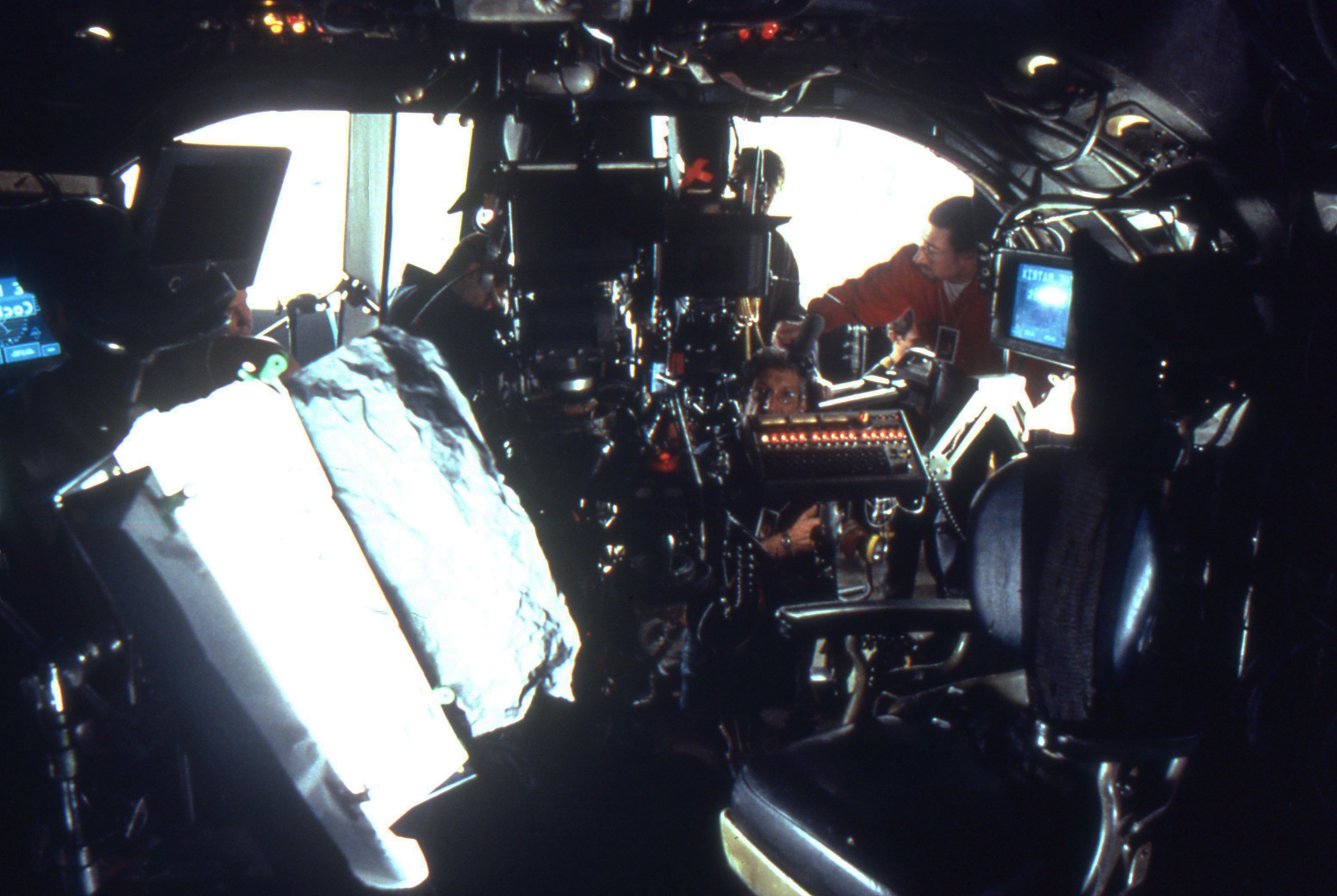

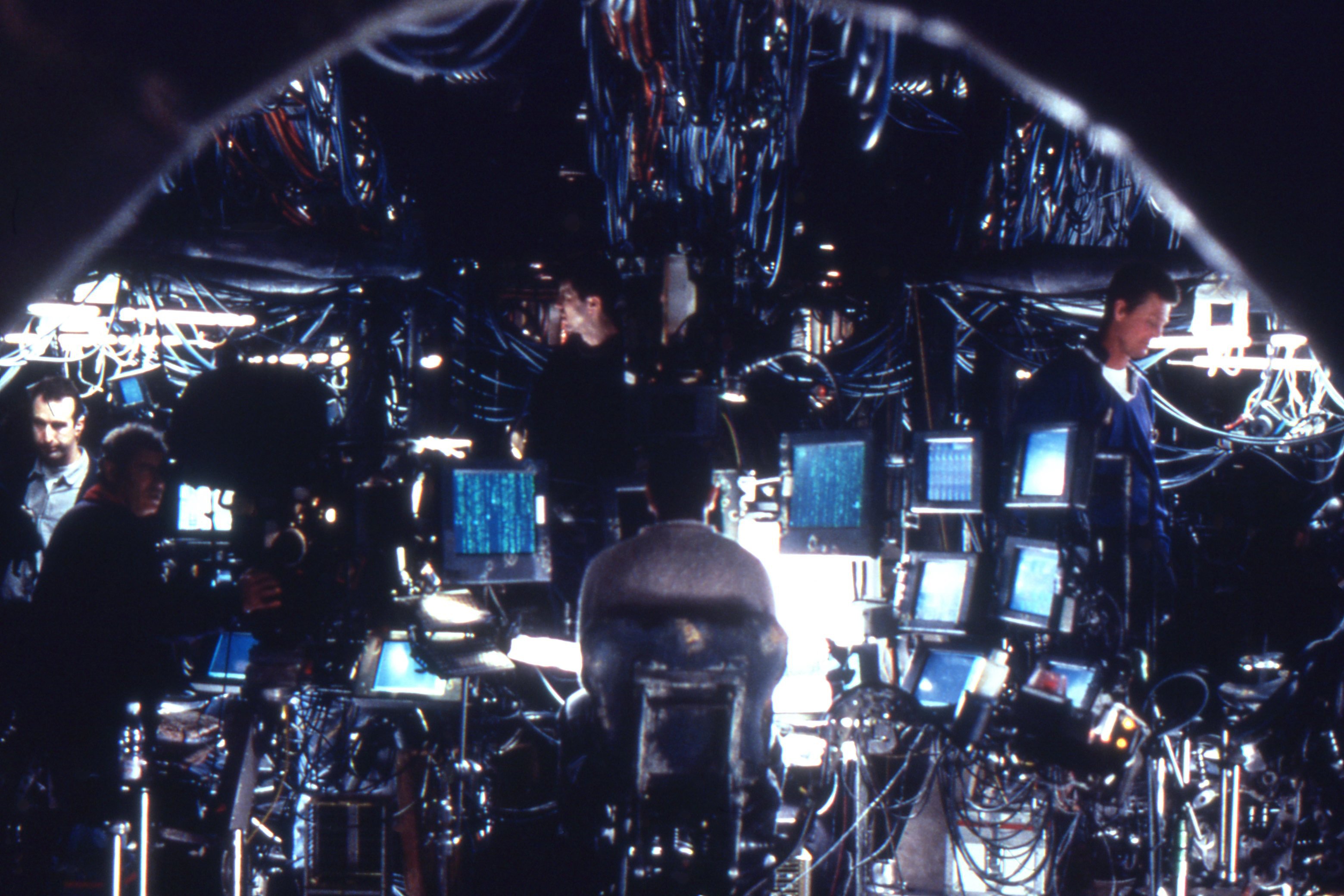

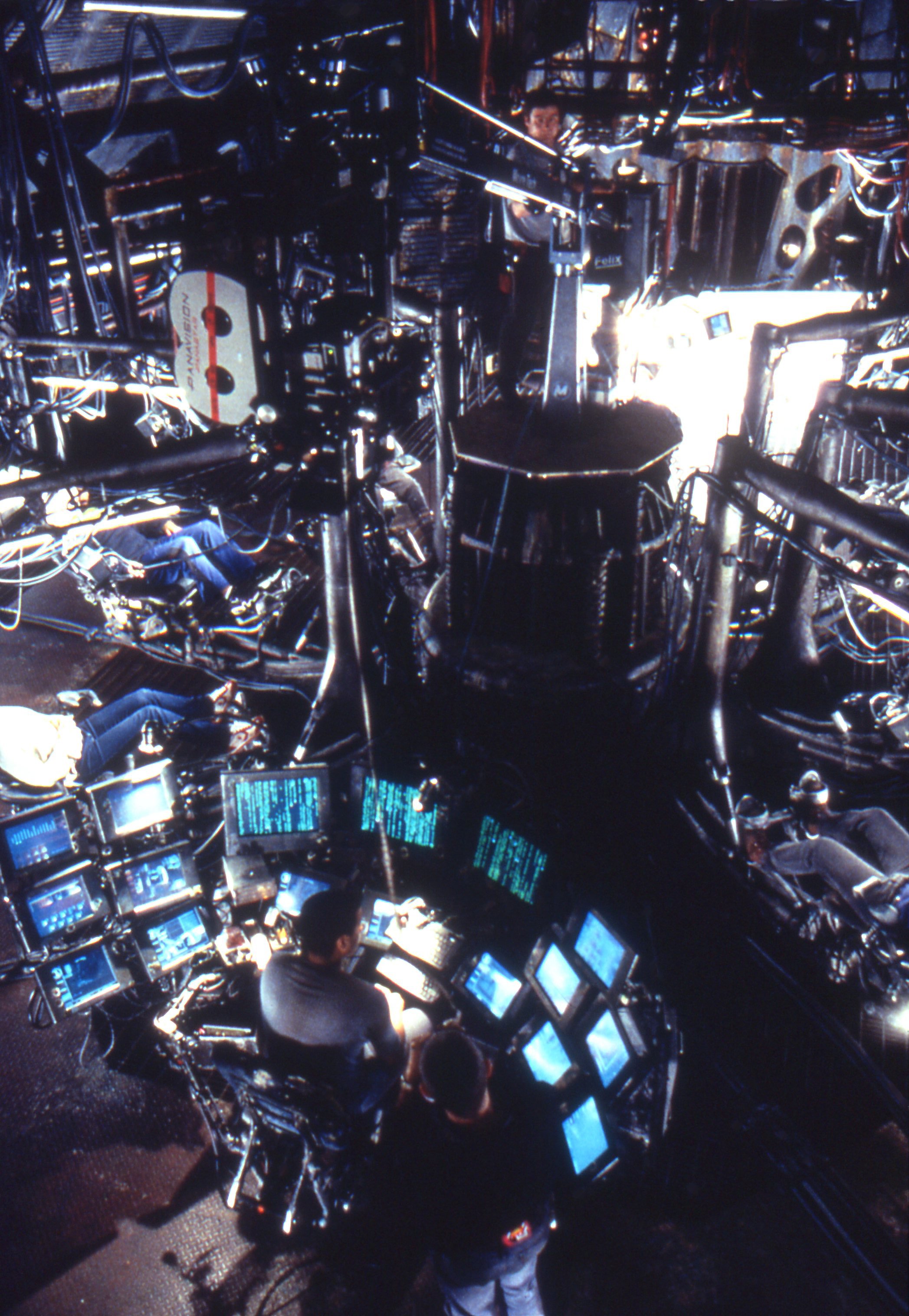

Once Neo is awakened from his pod-bound limbo and shown the true fate of mankind by Morpheus, he joins a small band of rebels that operate outside the controls of the Matrix. The members of this faction independently enter and depart the cyber realm in an effort to become more adept at altering the Matrix's virtual reality. To suit this purpose, the rebels have assembled a makeshift hovercraft, the Nebuchadnezzar, which they navigate through the sewers of the monolithic computer network.

"Inside the Nebuchadnezzar, the rebels have special chairs that hold their bodies in suspended animation as they feed their minds into the Matrix," Pope details. "The ship set was an incredible construction. It had a solid-steel center section that held up each rebel's chair, which was hydraulically articulated. The chairs were surrounded with monitors and various mechanisms, and the floor was a sort of porous grating. We shot hard and soft light up from below through the grating, although we never let that light hit the actors. They were always lit fairly softly with Kino Flo tubes that were either built-in above each chair, or set on stands. We also integrated a few MR-16s and Par cans into the design. Overall, the ship was kept pretty dark and slimy, and we had surfaces wetted down to get gleaming highlights on the structure."

Adds Garside, "Because of the nature of that set, we really couldn't use an overhead sail for ambience. The set was designed to come apart: the roof lifted up to the grid and the sides pulled out to the wall, leaving just the center section and chairs. Because of that, key grip Ray Brown and I had to build our rigs into the set, so that if the set moved, the lights were attached and it wouldn't alter the feel. There were gaps in the sides of the ship, but we didn't want to see what was outside. We therefore skimmed 2K Juniors with 1/4 CTB down the sides of the set to bring the relief out and create some depth."

Lobby Showdown

When Morpheus is captured by three Agents and held within a government office building, "Neo goes back into the Matrix, basically on a suicide mission, to save him," Pope explains. "No one has ever survived a battle with even one Agent, but Neo is going in to attack all of the government troops, the army and three Agents!"

Entering the building's lobby, Neo and his partner, Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss), are confronted with a dizzying onslaught of bullets and mayhem from the heavily armed troops. "Neo and Trinity come racing down the length of the lobby, shooting up everybody," notes Pope with a chuckle. "The stone columns in the lobby literally disintegrate, with huge chunks of stone spraying everywhere. For a lot of our high-speed work, we carried Clairmont's Wilcam-12, and a lot of the gunplay was filmed at 300 fps, which required Reg and I to light the set to about a T11 [while shooting with 79, at a base exposure of around a T2.8/4]."

"Because the Wachowskis were using wide lenses — such as 10mm and 14.5mm — we really couldn't light the set from the floor," Garside recalls. "We basically had to light it all from the ceiling with a big ambience, so again we had nearly 1,000 Par cans in the roof."

“The walls of the lobby were a very dark green,” Pope adds. “A lot of the action took place in two side colonnades where the overhead light wouldn’t reach, so I used some Dinos and Mini-Dinos on the floor for modeling in those areas. There were always at least eight or nine Dinos burning at one time through 12' by 12' and 8' by 8' gridcloths. I tried to play all of the light from one side, and we used very little fill light. However, if your main light source is soft enough, you really only need one source.”

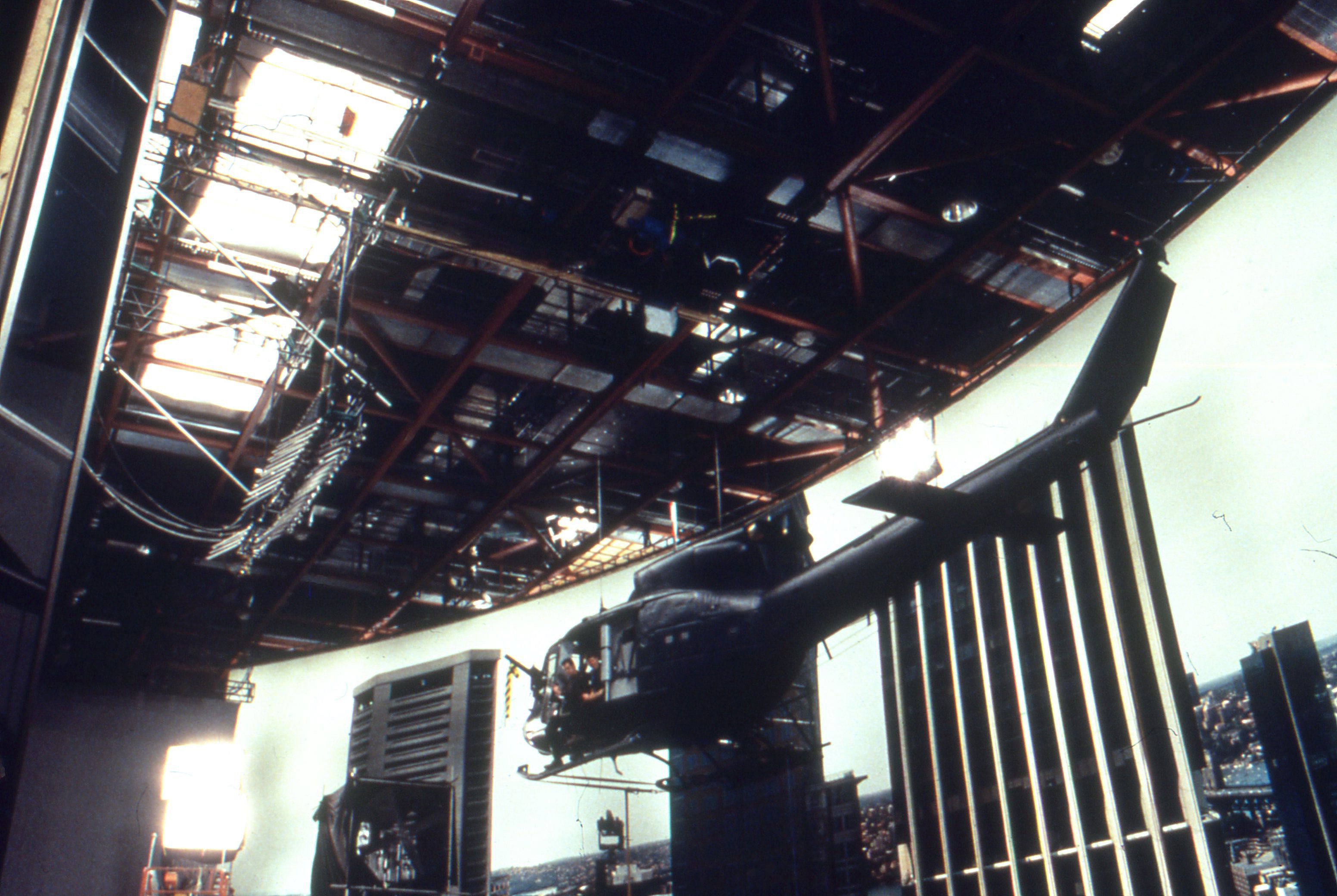

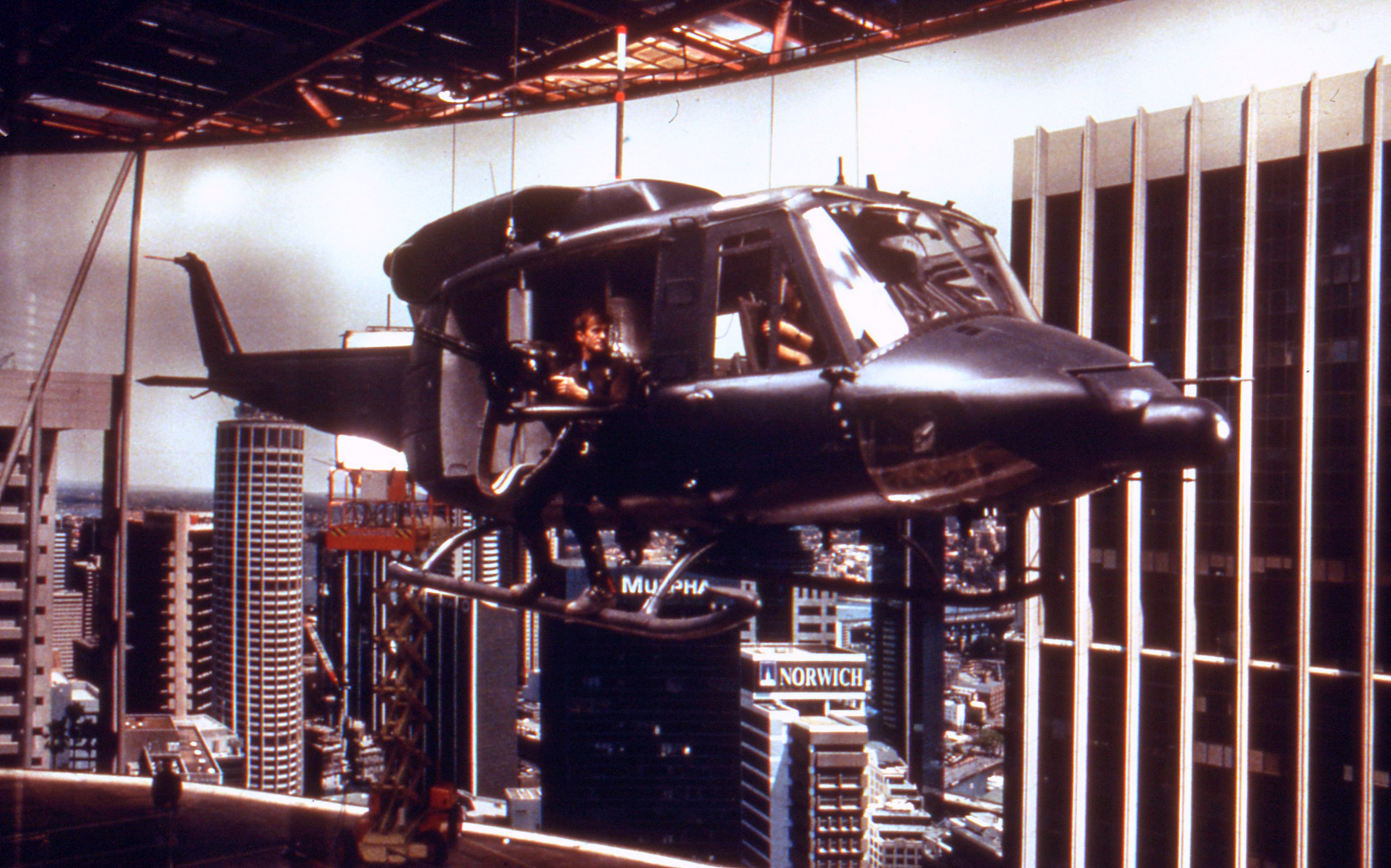

Aerial Assault

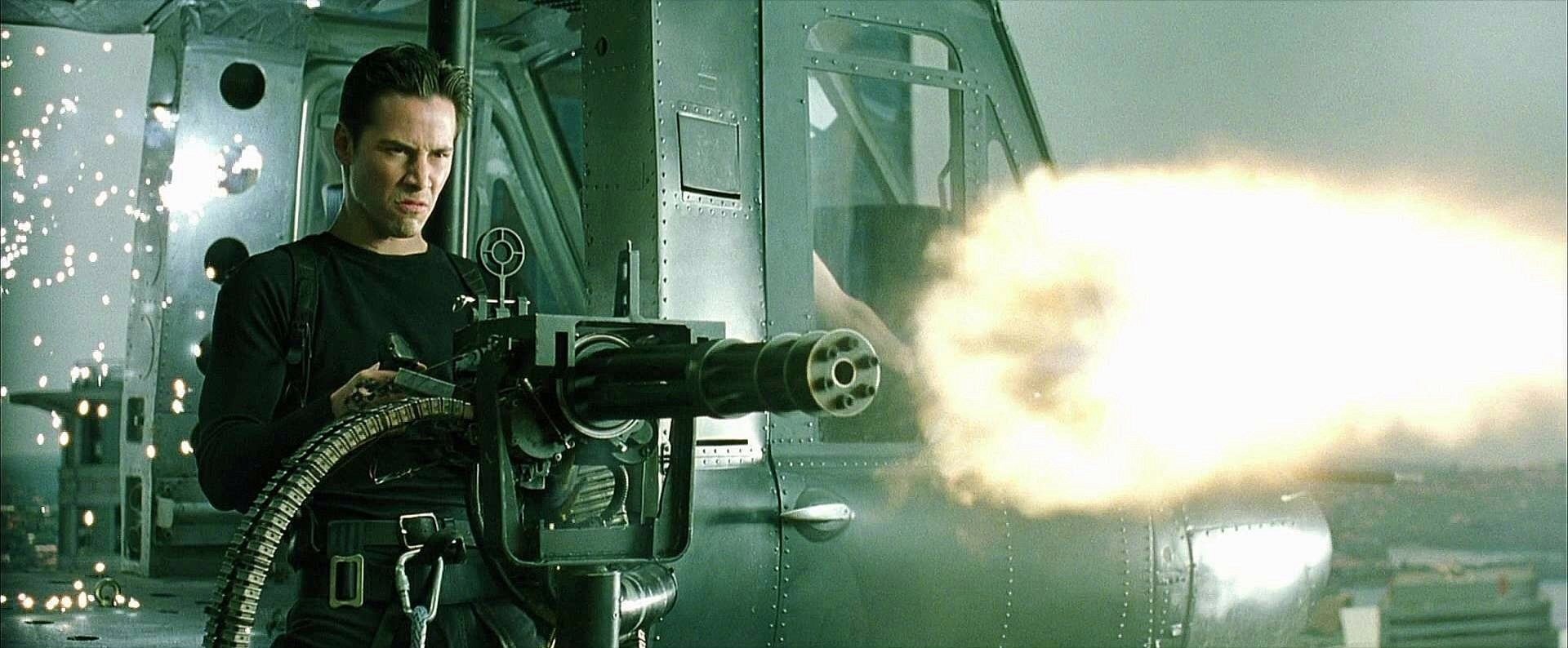

After Neo and Trinity wreak havoc on the lobby, the duo takes an elevator up to the roof, where they commandeer a helicopter. "In the helicopter, Neo and Trinity descend down the side of the building and see Morpheus being tortured inside one of the offices," Pope details.

"Since they've just blown up the entire lobby, the building's sprinkler systems have come on, and water starts filling up the rooms. We had a full-scale helicopter, which was flown by a rig attached to the stage perms; it could be lifted, lowered down and floated around. When the three Agents look up, they see the helicopter hovering in front of an enormous TransLight. Composed of several slightly altered shots of Sydney — with its sky corrected to white — the custom-made TransLight measured 190' by 40'. Again, we had to be able to shoot at 300 fps, so the set and TransLight had to be lit to a T11 when needed. Reg had a computer program that told us how many lights we'd need to achieve that. I think we had a total of 12,000 amps coming into the building."

"We had 200 5K Skypans on dimmers just for the TransLight," Garside adds. "In addition, we had 500 Par cans in the roof — again, aimed through a light gridcloth sail — to create some ambience over the helicopter. We also had to light into the helicopter, so we had four Dinos coming through 12' by 12' frames of light gridcloth, which I put on scissor lifts because the helicopter was suspended 20' above the stage floor. Finally, I had five more Dinos outfitted with narrow-spot bulbs [NSP] and rigged in the perms to give us highlights through the building's windows. The windows, incidentally, were also tinted, so when they were blown out, it gave the feel of light flooding in as they shattered. We then had to light the inside of the room, which we did with several Wall-O-Lites. Since the sprinklers come on, we built our own housings for the Wall-O-Lites: Hydroflex Kino Flo tubes clipped to reflector backings to make water-safe 8-bank and 4-bank units. Then we used those units through layers of light gridcloth."

"As a last element for the lighting in this scene," expands Pope, "I wanted to create the effect of sunlight strobing over the actors' heads due to the helicopter's twirling rotor blades, even though the blades would be added to the scene later with CG. To do that, I had two 70K Lightning Strikes units which were run through a precision fader to allow us to control the amount of strobe flashing in relation to the camera's specific frame rate. We aimed those at the actors from above. We first tried Unilux units, but the Lightning Strikes fixtures were much brighter.

"Because Neo blasts out the building's windows with a mini-gun aboard the helicopter," Pope explains, "the effects people [Brian Cox and Steve Courtley] had to create a pattern of bullet-hit effects, but they couldn't squib the glass because we'd have been able to see the wires. In front of and above the glass, they rigged hundreds of mortars that projected sand hard enough to shatter the window in a predetermined pattern. The walls in the room, as well as the people, were also squibbed in that same pattern. The water then had to come pouring out of the broken windows — all in one shot.

"We were shooting over Keanu's shoulder from inside the helicopter," Pope continues, "so we saw all of this happening in front of us as he fired the mini-gun. It was incredibly complicated stuff. In fact, we had to stage it twice, because on the first take, we could see the sand pass through the air before it hit the glass. To hide it, we flagged off some of the lights overhead — which was tricky, because we still needed to light up the front of the building as if it was daytime."

With the building's windows shot out, Morpheus makes a dramatic leap to the helicopter and freedom; he's barely caught by Neo, who dives from the helicopter after his falling friend. Suspended by a cable from the now-crippled chopper, Neo and Morpheus careen through the downtown buildings while Trinity looks for a rooftop to set the heroes down safely. "Most of this work was performed by the second unit from the ground, and the helicopter unit from an additional camera-helicopter," notes Pope. "For some key shots, Carrie-Anne actually learned to pilot the ’copter. For the shot in which Neo and Morpheus are dropped onto a rooftop, a large stunt crane was constructed on the highest part of a multilevel rooftop, about 20 stories above the street. We used the crane to swing the stuntmen onto the lower levels of the roof.”

Once Neo and Morpheus are safely grounded, the helicopter loses control and dives into the side of the building. "When the helicopter crashes," reveals Lana, "we see it exploding behind them in an almost supersonic wave that blasts out the building's windows — it's like a time-lapse shot of a flower opening."

"The helicopter crash was the type of elaborate sequence where storyboards are invaluable," explains Pope. "No shot in the sequence is a simple shot of reality. Many background motion picture and still plates had to be shot, from helicopters, window-washing units, and other buildings. A quarter-scale chroma-key green building was then erected — which was made of squibbed glass — that the effects people shattered in the 'expanding ring' pattern as the helicopter mockup was swung into the building on a specially-built crane arm."

Subterranean Brawl

“After Morpheus is freed, the trio is pursued down into a subway by the Agents," Pope explains. "Everybody manages to get out, however, except Neo. This is where Neo and the main villain, Agent Smith [Hugo Weaving], have their big showdown fight."

Like the previous sets, the subway had to be lit for both normal and high-speed photography. “Inside the station, the platform area had 8-square-foot ceiling sections, each of which had a fluorescent fixture built into them,” Garside notes. “Above each of these sections were 72 Par cans. The built-in fixtures were actually hollow, and we just aimed the Par cans down through them, angling them in such a way that the illumination felt like fluorescent light. When we were shooting at normal speeds, we had maybe 12 Par cans coming though each fake fixture, which were covered with 1000H. For high-speed work, we rigged the set so that each of the ceiling sections could be lifted out and replaced with 8' by 8' frames of light gridcloth; increasing the light value but not changing the quality of the light that much.”

"Because our sets were alternately lit to a T2.8 or a T11," says Pope, "all of the practicals had to be built so that they could accommodate both lighting levels. Many had to be specially made out of a heat-resistant resin. The [normal and slow-motion] shots don't match perfectly all the time, but it's close enough that the average viewer won't notice any difference. When you work for a long time at T2.8 and then suddenly shoot at T11, it's easy to make a mistake. At that level of light, you have to trust your meter more than your eye."

A Brighter Tomorrow

Interestingly, 150 show prints of The Matrix were treated to Technicolor's renewed dye-transfer "matricies" process. (See "Soup du Jour" AC Nov '98.) The remaining 4,350 release prints were struck on Kodak's new Vision stock.

Pope has nothing but praise for his Australian crew: "Reggie and his crew and key grip Ray Brown and all of his team worked incredibly hard on this film. They were solid as rocks and rose to any challenge. When I first laid out all of the lighting and physical requirements for this film, they said, “You’re kidding!' But when they realized I wasn’t, they said, ‘Well okay, let's do it!’”

The Wachowskis are equally enthusiastic about their director of photography, stating, “Bill Pope is the kind of cinematographer who really enjoys using black on the screen. There’s a certain [compositional] power in having deep, dark blacks. But beyond that, Bill also likes moving the camera, which we enjoy doing very much. Those two elements fit really well into the way we wanted to make our movie.”

Pope subsequently photographed the two Matrix sequels, as well as such films as Team America: World Police, Spider-Man 2, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, Spider-Man 3, The World's End, The Jungle Book and Baby Driver.

The Matrix was selected as one of the ASC 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.

Author Christopher Probst became a member of the ASC in 2018.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.