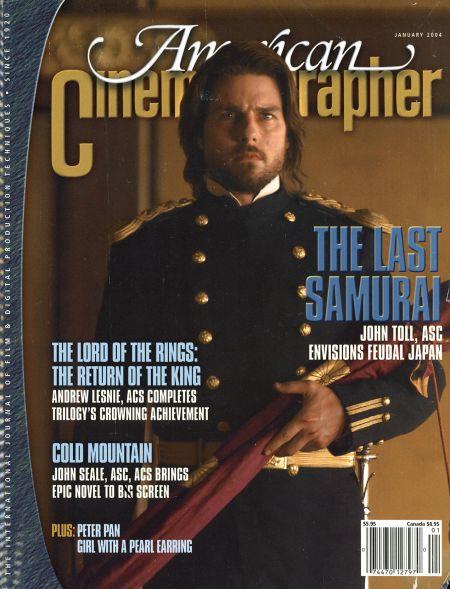

The Fate of Middle-Earth — The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King

Shot by Andrew Lesnie, ASC, ACS, this brings J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic trilogy to its thrilling yet bittersweet conclusion.

Unit photography by Pierre Vinet and Grant Maiden

The conclusion of the Lord of the Rings trilogy, The Return Of The King tells of the Fellowship’s final confrontation with the forces of the Dark Lord Sauron in the climactic War of the Ring, and of the mental and physical struggle of Frodo (Elijah Wood) and Sam (Sean Astin) to reach the heart of Mount Doom, into whose fires the One Ring must be thrown. Despite the ultimate triumph of good over evil, the story has bittersweet overtones, in that it concludes with the departure of Frodo and the Elves from Middle-Earth. “These films are about so much — friendship, loyalty, betrayal and destiny — that it’s impossible not to be affected by them, especially when they’ve been a part of my life for so long,” remarks the trilogy’s director of photography, Andrew Lesnie, ASC, ACS. “I know the experience I’ve had on this production will never be repeated.”

During a break in the filming of pickups in Wellington’s Stone Street Studios, director Peter Jackson told AC that “the third part of the trilogy has always been my favorite because now we’re heading directly toward the climax. We’ve had six hours of exposition, and now we get the intensely emotional payoff. All of the characters having been pushed to a point where life or death depends upon what they do at this time. The third movie is really the point of doing the entire trilogy; it’s the reason why I made the first two.”

“This trilogy has been a life-changing experience for everyone who has worked on it.”

— Andrew Lesnie, ASC, ACS

For Lesnie, The Return of the King is a “very different story and film than the previous ones. That’s what I like about the trilogy: the films don’t repeat themselves. Rather, the story undergoes constant and consistent transformation. The Return of the King isn’t as linear as The Fellowship of the Ring [AC Dec. ’01 ], which was very much about the different moralities of each place the Hobbits traveled to. The Two Towers [AC Dec. ’02] introduced narrative complexities and provided different photographic opportunities by virtue of opening up the landscapes and showing new cultures, such as the Rohirrim. The Return of the King, however, is much more about the subtext within each of the characters, and despite its scope, it’s an intensely personal story. It’s in this final film that the story really focuses on Frodo, Sam and the unfortunate Gollum. The physical ardor of their journey isn’t as important, story-wise, as their need to find the inner strength to fulfill their quest. As the title suggests, the other important narrative thrust is the ability of Aragorn [Viggo Mortensen] to acknowledge his destiny. So there’s a lot going on.”

Lesnie feels that one of his most important contributions to The Return of the King was “to be responsive to what the actors brought to a scene. For a film like this, as much as you plan your shots, the staging should always be actor-driven. You have to be receptive to what the actors offer when the scene is blocked through. They may offer something much, much better than what you’d imagined. I find that at the point of blocking, I come to understand the full strength of what the scene is about. Consequently, the technical choices become clear.”

A scene that has particular emotional resonance for Lesnie is the coronation of Aragorn as King of Gondor. “That scene is a great example of how there can be numerous emotional layers of subtext, some even apparently contradictory,” he explains. “The newly crowned Aragorn approaches the Hobbits, who kneel before him and declare, ‘You bow to no one,’ and Aragorn then bows to them, as does the whole crowd. On one hand, the scene is an uplifting, festive celebration — the war has been won and a new king crowned — but it’s also tender and poignant, perhaps even sad, because the Hobbits and the world they live in have changed forever. So although the scene has a vibrant look, it’s the action within that drives such moods. Return of the King delves into emotional complexities and layers that are very hard to quantify, so the best option was often to avoid crowding the performances with overt lighting. The audience needs to find their own meanings in what’s happening. We didn’t want to drive people so hard in one direction that they wouldn’t see any others.”

Much of the film’s action takes place in the Gondorian city of Minas Tirith, with Sauron’s armies attacking the multi-leveled city in the mistaken belief that Pippin is the ringbearer. The wizard Gandalf (Ian McKellen) is keen to exploit this situation, because with Sauron’s will bent to the destruction of Minas Tirith, Frodo and Sam are temporarily forgotten. Lesnie describes Minas Tirith as “a clean, pristine-walled city that’s about to be corrupted by an invasion. The city is built out of white stone, and we gave the whole of Gondor a classic, graphic, pewter look.

“However,” he continues, “if you let images become too monochromatic, it can create problems if there are color aberrations from different labs. The image reacts very quickly to a point of magenta or two points of green one way or the other, and the whole thing begins to fall apart. To avoid that, colorist Peter Doyle and I selectively boosted some of the earthy, warm colors and blues in Minas Tirith. When you have nicely saturated colors, it takes a lot to move them, so aberrations tend to be hidden.”

The spectacular nighttime sequences that show Minas Tirith under siege are punctuated by fireballs that are catapulted over the city walls by Sauron’s army. These were achieved through lighting as well as special effects. “To represent the fires caused by such an attack,” the cinematographer details, “we set up several Dinos that were gelled with half and three-quarter CTO, as well as some strips of #30 Red CalColor, and then patched into dimmer boards so they could be programmed to pulsate. We used the Dinos in conjunction with big flame bars, which were either sources or compositional elements in the foreground of particular shots. During principal photography on the set, we catapulted real, 4-foot-wide fireballs of compacted hay that were soaked in accelerant. It was quite dangerous. There isn’t really a flat surface anywhere in Minas Tirith, so sometimes those balls would splinter upon impact and start spot-fires, or they’d simply roll, often directly toward us! We didn’t bother with interactive lighting for the fireballs because the light they threw out was strong enough.”

In keeping with his philosophy of being responsive to actors’ performances, Lesnie approached the travails of Frodo, Sam and Gollum through the landscapes of Mordor on a scene-by-scene basis. “Tolkien’s trilogy is a prehistory of our world that we’ve always presented as real,” he notes. “Within that reality, even such a violent and turbulent place as Mordor has to be believable. Mordor is made up of several distinct places: Minas Morgul, Shelob’s Lair, Cirith Ungol, the Plains of Gorgoroth and Mount Doom. Each of these places has its own look in that they’re production-designed differently, but in terms of lighting, they don’t stray much from the basic parameters I’ve established. I didn’t want the lighting to detract from the human — or Hobbit — aspect by imposing too strong a style.” Colorist Doyle agrees that “the challenges of the Frodo and Sam story was to keep the frame looking interesting, while at the same time not departing from the color palette [that governs the look of] this part of Middle Earth.” The main colors used for these sequences were blue-greens for night scenes, and light green, contrasted with the reds and oranges from the fires of Mount Doom, for day.

As the Hobbits enter the lands of Mordor, they fall prey to Gollum’s trap and are attacked by the giant spider Shelob. The spider’s lair is a labyrinth, with claustrophobia-inducing tunnels twisting and turning for miles. Scattered throughout the tunnels are the remains of Shelob’s previous victims, who were either caught in her many webs or cast aside on the floor. During pickups for the Shelob sequence in Wellington, Lesnie points out that the lighting of these scenes takes on the tones and texture of classic horror movies. “I played the lighting from the floor as much as possible. That helps to create the feeling of an ever-present roof, enhancing the sense of claustrophobia. In situations like this, you’re lighting the walls and not the actors.” Lesnie combined hard, low-angle backlight with Kino Flos as soft key lights. Shelob’s lair is rendered in blue-green tones, which Doyle describes as “a fantastic cyan green. There are shots where the camera tracks around the wall of the set, and as it does, the colors shift a little toward the green or blue end, depending on the direction of the move. It creates a wonderful sense of interactivity.”

For a night scene in which Frodo is captured by Orcs, Lesnie used strong, aggressive colors. “Frodo is taken to the top of the tower of Cirith Ungol in Mordor, where an Orc and Uruk end up having an argument over his possessions,” he explains. “To create a strong sense of color contrast running throughout the scene, we lit the room with a red lantern in the center, which provides a few little splashes of color, and had blue-green patterned moonlight — a combination of half CTB and White Flame Green — coming through the broken roof. A hole in the floor provides the entrance to the watchtower from below. Under the hole, a group of Uruks is sitting around a fire, and to represent that I had a dimmed-down Dino bounced into a silver/gold reflector pulsing up through the entrance. It’s an assertively colorful scene that’s in keeping with the inherent threat of violence that characterizes Mordor.”

As Frodo and Sam near the end of their journey, they struggle to climb the fiery surface of Mount Doom. Recalls Lesnie, “To film the location sequences for Mount Doom, we went to Mount Ruapehu in the North Island’s Tongariro National Park, a volcano which only last century belched ash as far as Wellington. There, we shot scenes of Elijah and Sean climbing. We filmed in daylight with no 85 so the image would be blue. I added Dinos coming from low angles with various combinations of red gels on them for the lava effects. Once I’d desaturated the blue in the grade, I was left with almost monochromatic images, with strong reds providing color separation. To enhance the violent feeling of Mount Doom’s surface, we had heaps of smoke pots and fans going — it looks like the mountain is about to erupt. Inside the mountain, at the Crack of Doom, we had a forced-perspective set of the narrow ridge Frodo and Sam find themselves on. Underneath them is the molten lava Frodo has to throw the ring into, so I played a lot of the lighting up from below; because the ring’s presence in the place where it was forged sets off a metaphysical effect, we used a huge amount of interactive lighting. At the climax of the sequence, when Frodo puts on the ring and is attacked by Gollum, all hell breaks loose. We used red-gelled Dinos on a chase pattern in conjunction with other lights bounced into fabric reflectors being shaken by crewmembers. We also had Lightning Strikes units going off, and the cameras were being vibrated manually — virtually everything was moving. To suggest the heat created by the lava, we had an enormous number of steam pipes and hoses running throughout the set. Even when we were just standing there, it was a hot, dank environment.”

Frodo’s increasingly wretched appearance underscores his mental and physical struggle with the ring’s malevolent power. “As Frodo gets filthier and filthier, his skin starts to look like that of a coal miner,” says Fesnie. “I found that Elijah’s eyes, which are very bright anyway, really started to glow. By the time he’s standing over the Crack of Doom, claiming the ring as his own, he’s glaring at Sam through the tops of his eyes, and with all the light coming up from below, he looks like he’s bordering on insanity.”

Ever-present in Lesnie’s mind during exterior scenes was one of the film’s main visual effects: the thick, black Darkness of Sauron spreading from Mordor, which threatens to demoralize the forces gathering against the Ford of Mordor. “Whether during principal photography or while we’re doing these pickups in the studio, the visual metaphor of the black cloud billowing from Mount Doom is something I’ve constantly had to keep in the back of my mind,” he says. “Given that a lot of the Gondorian armor is monochromatic, I was a bit worried that the imagery could end up somewhat bland, so I suggested to Peter Jackson very early on that we should always be able to see past the clouds at the horizon level. That way, there’d always be a strip of contrast running through those sequences. I could then make the images quite dark, despite the fact that it’s the middle of the day, and still maintain contrast. I’ve tended to use backlight for those scenes, so when we were shooting up at the sky, the armor was always going to be delineated against the dark cloud in the background.”

The main battle between Sauron’s forces and those of Gondor and its allies takes place on Pelennor Fields. The larger setups of the scenes were filmed with hundreds of extras on several acres of farmland, while the smaller sections were shot on a prepared area roughly half the size of a football field at the Stone Street Studios. During the day, Lesnie placed 18Ks on Condors and boom lifts to provide backlight, while the low-angled sun, whose direct light was blocked by the large bluescreen, provided the ambient light. Key lights were provided by HMIs bounced into 12'x12' Griffolyns. In order to extend the shooting day into the cold New Zealand nights, Lesnie used a 50K Soft Sun to provide a broad ambient source. For tighter shots requiring more modeling, the Soft Sun was pushed forward to light the bluescreen, and smaller HMI units were bounced into Griffolyn to provide foreground ambience. “We had the usual turbulent New Zealand weather,” Lesnie reports. “However, virtually all of the skies are going to be replaced by the dark clouds of Mordor. To replicate the light coming from the bright strip of horizon under the dark skies, we bounced 6K and 12K Par lamps into the soft side of shiny 8-by-8 board reflectors.”

Doyle notes that “Pelennor Fields is also a good example of the image-sharpening techniques we’ve been applying since The Two Towers. The sharpening tools really get into all the metal and armor, providing amazing detail. We’re also using them to give more definition to the frame by helping direct your eye to different areas.” Adds Lesnie, “Because of the aggressively moving camera during the battle scenes, we’ve found that putting a selective power window just around the characters’ eyes and sharpening them helps keep the audience’s attention on the actors’ performances. We’re applying it only to the eyes, because sharpening tends to bring up the grain, which is more noticeable in the flatter areas, such as the cheeks. The performance is always in the eyes.”

The battle’s tide is turned by the timely arrival of Aragorn, who leads an army of the Shadow Host, the deceased Men of the Mountain who had broken their promise to Isildur to take up arms against Sauron many years before. To secure the services of the supernatural soldiers, Aragorn, Gimli and Legolas traveled through the infamous Paths of the Dead, a journey from which no man had ever previously returned. While inside the Paths, Aragorn entreats the Host to ride to battle with him, promising he will release them from their curse. “When we were first looking at the Paths of the Dead sequence, we had the notion of the spectral corpses emanating their own light so that when they appeared, they would fill out the dark underground caverns and provide fill light for the actors,” says Lesnie. “We decided, however, that such an approach would quickly negate the malevolence we wanted to build into the sequence, so in keeping with the classic horror look of Shelob’s Lair, we instead chose to under light the actors with 10Ks bounced into poly boards.”

After Sauron and his armies are defeated and the Fellowships victory is properly celebrated, the Hobbits head back to The Shire, where they find life virtually unchanged — a significant narrative departure from Tolkien’s book. “Everyone remembers The Shire from the beginning of The Fellowship,” says Lesnie, “but the difference is that the four Hobbits are not the same. Each is now a very different person. Should you attempt to make Hobbiton different because they now perceive it differently? I thought this was something that could best be realized through performance rather than look.” Lesnie says that for these scenes, he and Doyle sought to emulate the quality of late-afternoon light found in works by classical English landscape painters (such as Gainsborough) and some of New Zealand’s landscape photographers.

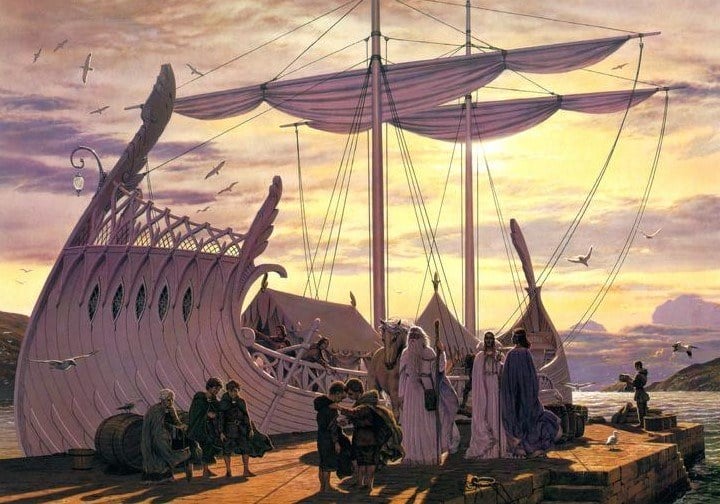

“The final departure of Frodo and the Elves from Grey Havens happens a long time after they’ve all gotten back to The Shire,” Lesnie explains. “People suffer through ordeals, but they continue living their lives. In the time between, Sam has married Rosie Cottontail and they’ve had children. One of Sam’s great virtues is that he’s forever optimistic. When you see his family situation, you realize that he’s achieving his hopes and dreams; in spite of what he has been through, he has seen good prevail. That’s an important message of the film. The actual departure of Frodo and the Elves at Grey Havens is another Elvish ‘beautiful moment’ — even in their demise, they go out with style.

As the story is now coming to a close, it seemed appropriate that the look for that scene be late afternoon, with a fantastic, golden sky. The reference for Grey Havens was a painting by Ted Nasmith of the Elvish ship on the harbor dock; it represented everything I wanted to do. We built several buildings of Grey Havens and the jetty on a greenscreen in B Stage. When we shot the departure with the actors, I asked for a great length of stage to be left clear. I cobbled together about six Dinos, made a full 85 frame to cover all of them, and just gunned that light straight down the studio from about 100 feet back — that was our late-afternoon sunlight. I also added some ambient light created by space lights, and when the actors were directly facing the Dinos, I applied a bit of diffusion to the lights. The whole scene was lit primarily by one source.”

Offering some final thoughts on his epic cinematographic undertaking, Lesnie says, “This trilogy has been a life-changing experience for everyone who has worked on it. The same crews have returned each year for the pickups, with New Zealander Dave Brown providing valuable support as chief lighting technician, along with the excellent cinematographers Richard Bluck and John Cavill, and key grips Tony Keddy and Harry Harrison. Everyone’s proud to be part of such a momentous piece of storytelling as The Lord of the Rings. These films show that love and the tender compassions of friendship, loyalty and courage can overcome a world of hate and fear. In the cycles of human history, the salient lessons expressed in Tolkien’s trilogy have made the films a timeless adventure.”

You'll find our coverage with Lesnie on Fellowship of the Ring here and The Two Towers here .

The cinematographer died at the age of 59 on April 27, 2015, after a brief illness. You'll find our complete In Memoriam remembrance here.

TECHNICAL SPECS

Super 35mm 2.35:1

Arriflex, Moviecam and Mitchell cameras

Zeiss and Angenieux lenses

Kodak EXR 50D 5245, EXR 200T5293, Vision 500T 5279, S0214

Digital Intermediate by The PostHouse

Printed on Fuji 3513D

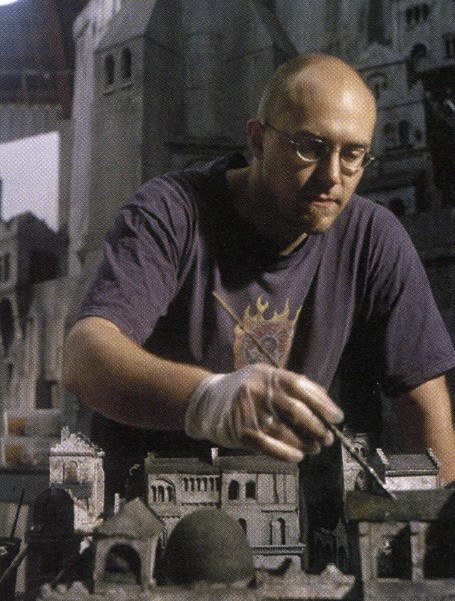

Miniatures Add Grand Scale

An integral component in The Lord of the Rings trilogy has been the production’s miniatures unit. Located in an inconspicuous building in Rongotai, a suburb of Wellington, and led by Academy Award-winning visual-effects cinematographer Alex Funke, the miniatures unit shot for more than 900 days on the epic production. A modelmaker puts the finishing touches on a miniature rooftop. “Peter Jackson always intended miniature photography to be the means by which a lot of the large environments, such as the stairs of Khazad-Dum, would be created,” says Funke. “It was simply not feasible to build the stairs as an entire live-action set. Also, while it was possible to transform many of New Zealand’s natural locations into Lothlorien, Mordor or Fangorn Forest, they were always going to need extra elements, such as set extensions, to make them totally believable as parts of Middle-Earth. Miniature photography is a great way to accomplish this. Miniature sets can be fully detailed by our model technicians directly to camera, and fine adjustments are interactive, quick and simple.”

Funke believes that miniature photography also lends visual effects a distinctive sense of realism. “At some subconscious level, viewers can tell when they’re seeing real photography,” he remarks. “So in the interest of telling a believable story, the more actual camera elements you have, the better. That’s the basis of Peter’s brief: to use the maximum number of photographic elements.”

From the commencement of principal photography in October 1999, the trilogy’s director of photography, Andrew Lesnie, ACS, worked closely with the miniatures unit to establish the lighting styles that would run throughout the films. “We sat down with Andrew regularly and went through the general approaches to scenes, detailing the key-to-fill ratio, colors used, contrast, texture of the light and so forth,” explains Funke. “We constantly and carefully referenced what he was doing on set or on location in order to match our photography to his. We were lucky to have Dave Brown, the first-unit gaffer, as our information pipeline; he kept a concise record of everything that was shot, which he passed on to us. Our other main source was the art department, in particular the paintings and drawings of Alan Lee and Jeremy Bennett. They painted virtually every shot. It was a wonderful treat to be involved in a film that was so beautifully art-directed, and that had so many production illustrations. It made our lives much easier.”

Funke says the miniatures unit’s shots were obtained in several ways: “Some of our shots were driven by ‘Tech-B,’ in which a live shot was exactly tracked and the motion control move file was sent to us for matching on the miniature set. Other shots we matched visually from animated previsualization scenes. For the ‘mini-leads,’ each shot was initially planned out with the aid of a handheld video camera, with the key positions of the camera move established by markers placed on the set.” Adds motion-control operator Henk Prins, “It’s basically the same approach as animation key frames. Each marker represents a specific point in the shot, with the space between the markers representing a certain number of frames. We then go through the move slowly to find out what the obstacles might be, and to readjust the key markers as necessary. In effect, this adds or removes frames. Then it’s simply a matter of refining the shot. The process is quite tricky, because there’s often no physical latitude — the lenses are almost touching the walls of the set.”

The miniatures unit used seven cameras: three Fries Mitchells; Funke’s own rackover Mitchell, which was linked to a ‘Thing-M’ camera controller; and three of the new Arri 435-Advanced motion-control cameras. “The Mitchells have been the mainstay of motion control for many years,” says Funke, “but since the middle of The Fellowship, we’ve also been using the Arri Advanced, which is a fantastic camera for motion control. For years, various filmmakers have tried to convince Arri to turn the 435 into a motion-control camera, and I’m happy to say we were the ones who finally got them to do it. We worked closely with Arri to solve the problem of the camera’s separate motors on the shutter and the movement, which previously prohibited it from running at motion-control speeds. Fortunately, we have a great in-house electronics engineer, Chris Davison, who was able to test the camera and work with Arri to get it up to speed, so to speak. The Arris swing over viewfinder let us look through the camera even in the most awkward of setups, which is a godsend for miniatures work. I think it’s the ultimate effects camera.

“For lenses, we used a Praxis snorkel, which is wonderfully sharp, and a Revolution snorkel, another great piece of equipment. The Revolution can roll the image optically, which came in handy for a lot of the flying shots on Minas Tirith and other sets.”

Funke notes that “a lot of very clever people worked in the miniatures unit on this project. One effect of this was that we significantly streamlined our referencing passes. The digital folks always want to have color references, which we used to shoot on flat color charts. That was a bit time-consuming because we had to point the chart toward the key, then the fill, and so on. One day, Alastair Maher, our master painter, came up with the idea of painting some balls with the exact colors from the chart. The gray ball gave the digital boys the nature of the shadow transition, while the six colored ones provided a three-dimensional color chart that had the key and the fill at the same time. It’s a handy innovation that worked beautifully.”

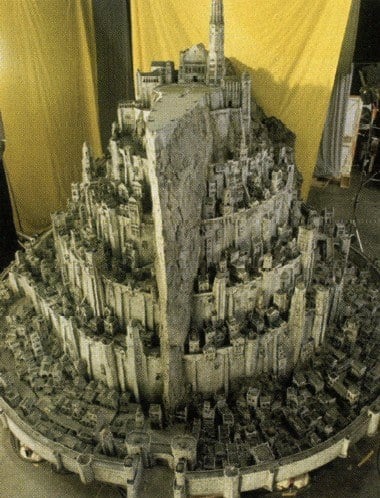

One of the most heavily used miniature sets in Return of the King is the Gondorian city of Minas Tirith, the centerpiece of a huge battle. Constructed in 1/72 scale, the buildings of Minas Tirith were initially built to be filmed in long shots only. “The first time Peter saw it, he said, ‘That’s a great set. We need to do some vertiginous, Star Wars-style trench shots,’” Funke recalls with a laugh. “Minas Tirith had never been designed to be shot from the back or in close-up, let alone in shots where the lens is virtually scraping the paint! So we had to go through the whole set and rebuild all the buildings, streets and so forth with much more detail. A good example of the type of shots Peter likes is one in which the camera follows a fell-beast with a Nazgul rider on it as it careens over the city streets. The camera then cuts around 180 degrees and flies backward, in front of the fell-beast. We used the Revolution snorkel for a lot of the shots down the narrow Minas Tirith streets, because we could roll and bank while we flew between the buildings.”

For reasons of practicality, many sets had different sections constructed in multiple scales. “Sauron’s tower of Barad-Dur, the main part of which is 1/166 scale, is a good example of using multiple scales,” says Funke. “Peter wanted to have the camera skim over the bridge and the heads of the marching ore army. It was physically impossible to get the lens in that close with the 1/166-scale set, so we had to build a larger scale version of the bridge, which was shot separately and then combined digitally with the rest of the set. It’s very common to combine different scales in this manner. A huge amount of Minas Tirith uses a mixture of 1/72 and 1/14 scale, while a few special set pieces are 1/35. Minas Morgul was shot in 1/40 and 1/120 scale, depending on how wide the shot was — 1/40 if we were creeping across right in front of the gate, 1/120 if we were supposed to be 500 meters above it. Helm’s Deep, which was 1/35 scale, was actually the ‘proof of concept’ set that Peter had built to help sell the project all those years ago.

“Peter wants to knock the audience’s socks off with Return of the King,” says Funke. “He wants them to see things they’ve never seen before. This film is enormous in terms of both the emotional content and the action; everything is bigger, wider and certainly more complex. This film has as many effects shots as the first and second pictures combined. I believe that this trilogy has given a shot in the arm to miniature photography. If the audience is thinking about the process, then we’ve lost them, and we’ve failed to do our jobs. We need to do the work, then erase our tracks and disappear.”

— Simon Gray