Lost Highway — Highway to Hell

Cinematographer Peter Deming lends creepy noir ambience to director David Lynch’s latest detour.

Unit photography by Suzanne Tenner

“A work of art in itself is a gesture and it may be warm or cold, inviting or repellent”

— Robert Henri, The Art Spirit

On a sunny December day in the Hollywood Hills, David Lynch sits in a deck chair on the outdoor patio of his filmmaking headquarters, a two-story modernist building that houses the aptly named Asymmetrical Productions. He is surrounded by the tools of the painter’s trade: an oversized wooden easel, drippy paint cans, a scattered selection of brushes. Resting against a nearby wall is an unfinished example of his oeuvre: a large chunk of roast beef adhered to a canvas with an acrylic glaze, flanked on either side by the similarly embalmed corpses of a tiny frog and sparrow. Scratching at the salt-and-pepper stubble on his unshaven chin, Lynch appraises his creation. “That roast beef has gone through a strange metamorphosis,” he says, folding his arms. “It was bigger when I started, but one day a squirrel came by and took a big hunk out of it. I'm kinda workin' with it.”

The line is classic Lynch, a collision of avant-garde eccentricity and folksy good humor. It’s quotes such as this that have led media pundits to lampoon the director as some sort of cinematic idiot savant — the weird but brilliant neighborhood kid who occasionally comes over to show off something repulsive that he’s dug up in his backyard. But the David Lynch that I encounter is clearly no fool; he is well aware of his image, and is most likely its canny architect. This is, after all, the man responsible for Eraserhead, the ultimate midnight movie; the director who unleashed Dennis Hopper’s psychotic alter ego, Frank Booth, upon unsuspecting audiences in Blue Velvet; the same David Lynch who once staged a one-man home invasion of the entire nation, swamping suburbia's television sets with the outlandish images of Twin Peaks He is, in short, the high llama of existential horror, hero to all who find life to be just a little bit strange.

“Stories have tangents; they open up and become different things. You can still have a structure, but you should leave room to dream.”

— David Lynch

Still, for someone who at various points in his career has been branded “the Czar of Bizarre,” “the Wizard of Weird” and “the psychopathic Norman Rockwell,” Lynch seems a pleasant enough fellow. When asked to explain how his rather unique thought processes conspire to conjure up his cinematic visions, the director assumes a sincerely thoughtful expression. “Everything sort of follows my initial ideas,” he offers. "As soon as I get an idea, I get a picture and a feeling, and I can even hear sounds. The mood and the visuals are very strong. Every single idea I have comes with these things. One moment they’re outside of my consciousness, and the next moment they come in with all of this power.”

But what is it that triggers these transcendent states? “Sometimes if I listen to music, the ideas really flow,” Lynch offers. “It’s like the music changes into something else, and I see scenes unfolding. Or I might just be sitting quietly in a chair and bing! — an idea will hit me. At other times, I might be walking down the street when I see something that's meaningful and inspires another scene. On anything that you start, fragments of ideas run together and hook themselves up like a train. Those first fragments become a magnet for everything else you need. You may remember something from the past that's perfect, or you may discover a brand-new thing. Eventually, you get little sequences going.

“Before you think of anything, the whole landscape is open,” he concludes. “But once you start falling in love with certain ideas, the road you're on becomes very narrow. If you concentrate, ideas will come to that narrow road and finish it.”

To this point in his career, Lynch has led movie audiences down some very twisted roads indeed. This time around, with the help of cinematographer Peter Deming (Evil Dead 2, Hollywood Shuffle, House Party, Drop Dead Fred, My Cousin Vinny, and the upcoming comedy Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery), he has unleashed Lost Highway, a neo-noir nightmare that plays like an unholy marriage of Body Heat and Altered States. Violent, non-linear, and shockingly odd, the film may baffle and even offend many viewers, but it certainly reaffirms Lynch’s considerable talents as a visualist.

The plot, such as it is, tracks the strange tale of Fred Madison (Bill Pullman), a jazz saxophonist whose marriage to a dour, raven-tressed sex kitten (Patricia Arquette) is decidedly on the rocks. Shortly after someone begins breaking into the couple's home and videotaping them as they sleep, the wife is murdered, and Fred is ushered to an amenity-free suite in the Graybar Hotel (a.k.a. prison).

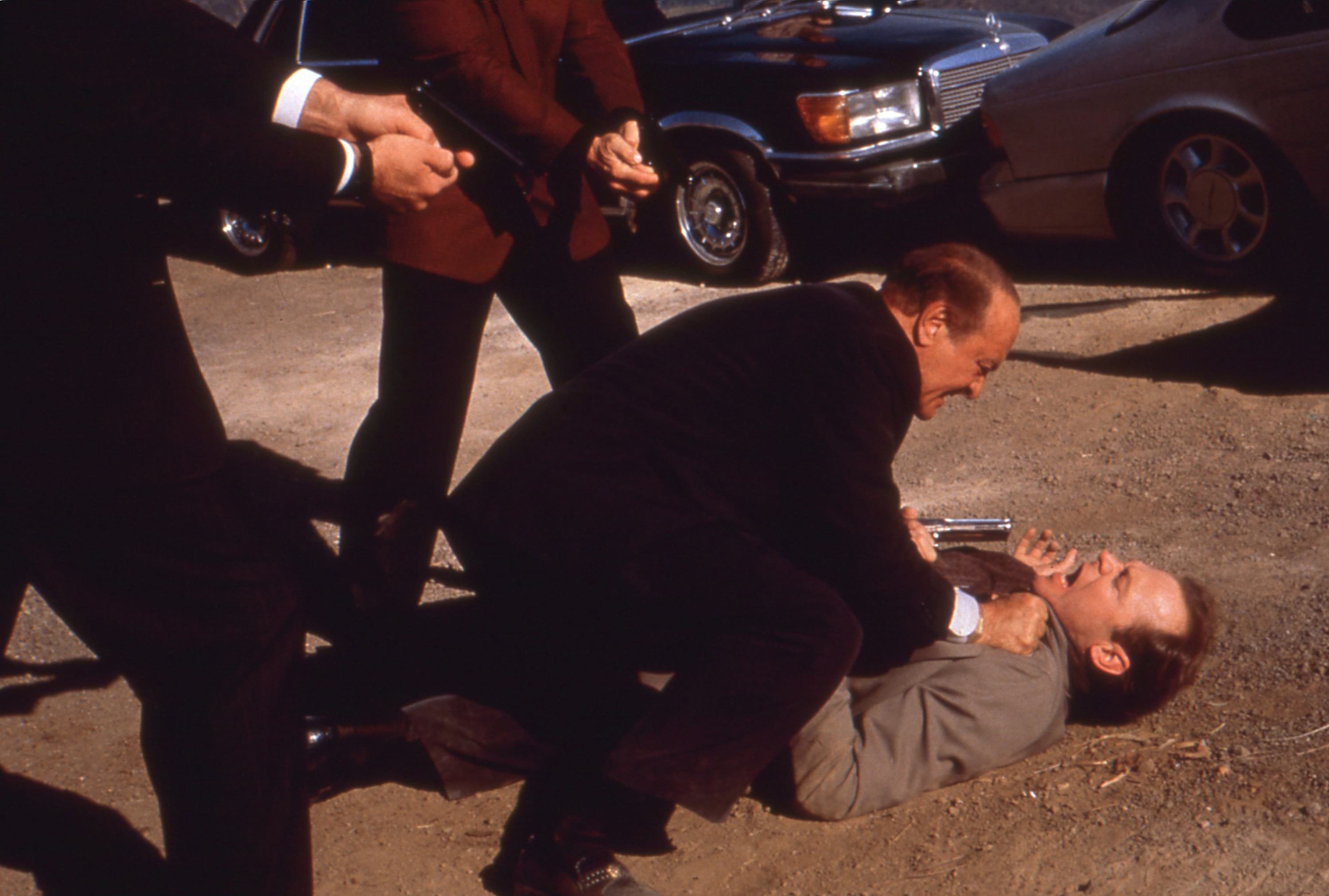

The setup is textbook film noir, but things soon takes a sharp turn toward the surreal. While languishing in his cell, Madison suddenly and inexplicably morphs into a teenaged garage mechanic named Pete (Balthazar Getty). Released from the clink by the baffled authorities, who tail his every move, Pete soon finds himself lusting after the sultry blonde moll (Patricia Arquette again) of a short-tempered crime boss (Robert Loggia). His infatuation gets him in dutch with the gangster, who subsequently employs a full arsenal of scare tactics — such as introducing the youthful grease monkey to a truly bizarre mystery man (Robert Blake) who has no eyebrows and the apparent ability to be in two places at once.

“Film noir has a mood that everyone can feel. It’s people in trouble, at night, with a little bit of wind and the right kind of music. It’s a beautiful thing.”

— David Lynch

All of this, of course, must be seen to be believed, which is no doubt part of Lynch’s master plan. Early press notes for the film described it simply as “a psychogenic fugue,” and the director himself offers no further hints about the movie's true meaning. “The unit publicist was reading up on certain mental disorders during production, and she came upon this true condition called ‘psychogenic fugue,’ which is where a person gives up himself, his world, his family — everything about himself — and takes on another identity,” Lynch relates. “That’s Fred Madison completely. I love the term psychogenic fugue. In a way, the musical term fugue fits perfectly, because the film has one theme, and then another theme takes over. To me, jazz is the closest thing to insanity that there is in music.”

Some viewers may prescribe a straitjacket for Lynch after experiencing Lost Highway, but adventurous film-goers will be treated to a torrent of dazzling images that defy indifference: a pitch-dark hallway that looms like a tenebrous abyss; Pullman's transformation into Getty, a sequence which seems inspired by a tab of bad acid; an opulent mansion that serves as a proscenium for porn; a nocturnal interlude of dusty desert coitus caught in the headlights of a car.

Like most of Lost Highway, these scenes have the febrile quality of a dream. By his own assertion, Lynch is "not an intellectual thinker," but an instinctual artist whose primarily motivations are mood, texture, and emotion. "Film noir has a mood that everyone can feel," he says. "It's people in trouble, at night, with a little bit of wind and the right kind of music. It's a beautiful thing."

In order to interpret Lynch's existential directives, his closest collaborators must attune themselves to his singular mindset. Lynch's longtime production/costume designer, Patricia Norris, says that she and the director have developed a strong creative kinship after years of working together. "We both have the same idea of what 'ugly' is — in terms of both decor and people," Norris submits. "All rooms come out of people, and if you understand who the characters are, you understand how they live. Most decorating conveys what's not written, and gives you a sense of the people. In Lost Highway, for example, the porno guy's mansion is really awful-looking — over the top and in bad taste. Everything is too big, and it looks as if he probably had someone else furnish it for him. We took a very different approach to the Madisons' house, because we wanted their relationship to be mysterious and nebulous. We decorated their place very sparingly with the kind of jazzy, Fifties style 'atomic furniture' that David favors; the look was basically 'a phone and an ashtray.'

Although Deming has not worked with Lynch for nearly as long as Norris, he benefited from his prior experiences with the director on television commercials, the short-lived television series On the Air, and the HBO omnibus Hotel Room. "David's not a big fan of prep; he doesn't like to be pinned down too much," Deming says. "Before shooting began on this film, we only talked specifically about two scenes: the first involved the hallway in Fred Madison's house, and the other was the love scene in the desert. We discussed different levels of dark — dark, 'next door to dark' gradations like that. To figure out exactly what he meant, I would reference things we had done together, or other work he had done. The colors David was most interested in were browns, yellows and reds. We wound up shooting a lot of the film with a chocolate #1 filter, which helped me get the look that David wanted. The lab felt that it was the most difficult filter to reproduce in timing.

"In testing, I ran into a bit of a problem using the chocolate filter at night," he submits. "The filter factor was a stop and a third, and it just ate up the shadows; you couldn't see into the shadow areas at all. Knowing the way David likes darkness, the chocolate filter was too much of a wild card when we were shooting at the low end of the exposure curve. We tried using chocolate gels on the lights, but that also proved to be a little too thick.

“I know what David likes; if he had his way, everything would be a little bit underexposed and murky, which is murder for me.”

— Peter Deming

"What I ended up doing was having Ron Scott, the timer at CFI, time in the effect to the scene. I'd give him two gray scales: one normal and one with the filter in the camera. He would match the normal one to the filtered one and apply that correction to the whole scene in varying densities. It wasn't my preferred way of doing things, but in the long run I think it was better because it gave the night scenes a slightly different look, even scene to scene. David grew to like the workprint he had watched for six months, and he didn't want to change that. I did one timing for the movie which was fairly consistent with the chocolate look we had designed for the day work, but it wasn't really happening, so we went back to what we had in the workprint to a large degree, improving it in places where it wasn't quite right. We wound up with a movie that has a different and nonuniform look."

Working in true anamorphic widescreen (2.40:1), Deming shot most of the film on Eastman Kodak's 5293 and 5298 stocks, and always deployed a Fogal stocking behind his lenses. He says that his choice of stocks was dictated by practical considerations and plain common sense. "Even when we were outside, we would somehow always end up shooting late in the day or under trees," he submits. "With the chocolate filter and some 85 correction, I really couldn't get away with anything but 93 — which was fine, because I like the 93 a lot. Normally, I shot 93 when I had enough light. I used the 98 for anything that took place at night. I might have done things differently if this hadn't been an anamorphic film, but with anamorphic you have to get at least a 2.8 whenever you can to make it look really nice. Sometimes we were a little below 2.8, and on one or two occasions we had to shoot wide open. I would shoot 93 more at night on a flat [1.85] movie, when you can shoot with a lower stop."

Deming says that his biggest challenge on the show was trying to accommodate Lynch's love of dark, inky visuals. "It was a struggle," he concedes. "I know what David likes; if he had his way, everything would be a little bit underexposed and murky, which is murder for me. On this film, I often found myself riding the bottom edge of the film's latitude. I didn't want to overexpose the images and print them down, because they would have had too much contrast. I wanted the overall look to be low-contrast in relation to the day work at the Madison house and in the rest of the movie."

Scenes within the Madisons' home — a practical location with low, seven-to-eight foot ceilings — posed a number of logistical difficulties. Although the filmmakers were able to alter the structure a great deal — by replacing the living room's large picture window with two very small vertical windows, and adding a skylight — the house's cramped interior forced Deming to plot out some very economical lighting setups. "It was one of those situations, particularly in the daytime, in which we just put lights where we could," the director of photography relates. "For daylight scenes, we were coming in from the outside, primarily with HMI Pars. We also bounced light down through the skylight. Most of our fill lights were Kino Flo banks, which allowed us to keep down the obvious shadows on the walls. The bedroom was a little different. We used a Dino on a Condor outside because there was a good-sized window we could work with, but there was only one day scene in the bedroom."

Night scenes at the house further complicated matters for the crew. "Usually in a setup like that you would work off practical light sources," Deming says. "That's what we did most of the time, although there were scenes without any visible practical fixtures; in those cases you just put something up and hope it's not too bright and obvious. For the night stuff we used a lot of paper lanterns. When you're shooting anamorphic, you normally have a lot of room below the frame line; usually you have room above as well, but not at the house we were using. We'd hide lights and hang them and jam them in corners where we could. Sometimes we would pin bounce material and shoot a light through the shot; because there was no smoke you wouldn't know it. My gaffer, Michael Laviolette, made a hard internal rig for the lanterns that took two 500-watt Photofloods. So we were dealing with a 1K light which, even with heavy diffusion on a lantern, was a lot of light in a small place like that. The lanterns were made out of pretty thick paper. Sometimes when we were dealing with a bigger set we would use an 8' x 8' light grid and a 12' x 12' muslin."

For certain key scenes, super-minimal lighting schemes were employed to great effect. A particularly impressive example of this strategy is the filmmakers' sepulchral rendering of the Madison home's main hallway, which has a foreboding quality reminiscent of the work of one of Lynch's favorite painters, Francis Bacon. Achieving this look required some deft interplay between the various crew- members.

Fortunately, the hallway was a setting we could control, even though we were shooting at a real house," says Deming. "Patty Norris and her crew physically altered the structure, making the hallway as long as possible. She also helped me by putting Bill Pullman in dark clothes, and by painting the walls a color that wouldn't reflect too much light. To cap things off, we hung a black curtain over the windows at the end of the hall."

Because the building's ceilings were so low, Deming opted to light the space primarily with a single, slightly diffused 2K zip light suspended directly above the camera. He used cutters and black wrap to perfect the angle of the light, relying on the high-speed 98 film stock to do the rest. "The 98 can really pick up details in the dark, so I knew that we were in trouble if the end of the hallway didn't disappear to the naked eye," says Deming. "David feels that a murky black darkness is scarier than a completely black darkness; he wanted this particular hallway to be a slightly brownish black that would swallow characters up. After we had finished the shot and sent it to the lab, I called the color timer and told him, 'As Bill Pullman walks down the hall, he should vanish completely, because if I see him down there I'm never going to hear the end of it.'"

The utilization of Kino Flos lent an eerie ambience to other sequences in the house. In one shot, Bill Pullman steps into a hallway so dark that he seems to be walking through a wall. A single Kino Flo created the mere hint of depth along the sides of the hallway entrance. The next scene shows Pullman gazing at his reflection in a mirror within the tomb-like confines of a small room. "The spot where David hung the mirror was only about six feet high," Deming says. "We put a Kino Flo up above, gelled it with chocolate and cut it severely. It was the only thing I could use to keep Bill from looking too ghoulish. We shot that the first day, and when it came up in dailies I thought it was underexposed. After the lights in the screening room came up, I said to David, 'We need to do that mirror shot again.' He looked at me as if I were crazy and replied, 'No way, I love that shot!"'

The filmmakers veered toward the opposite end of the photographic spectrum while shooting a hallway scene set within the opulent mansion of a porn-peddling hustler (embodied to oily perfection by Michael Massee). As a disoriented Balthazar Getty stumbles along the passageway, it begins to spin kaleidoscopically amid a barrage of lightning effects provided by two large, old-fashioned carbon arc machines. "Lightning is an issue that's very close to David's heart," says Deming. "He doesn't like electronic lightning machines, because the look they create is very clean. With carbon arcs, there's a certain color-shift in the flashes; they sort of warm up and cool off. In this particular scene, one of the units we used was bouncing off two mirrors aimed at the end of the hall, and the other was positioned above a skylight. We had the camera and another smaller lightning box on a doorway dolly, and we tracked backwards as Balthazar walked toward us. I had a tiny eyelight on him, and the camera was attached to a tilting Dutch head.

"To make everything spin, we used a Mesmerizer; it's an aspherical element that clips onto the end of the lens, and you can rotate it. When you use it with a flat lens, the image will squeeze and get wider as you spin it. As we were dollying, I was Dutching the camera and spinning the Mesmerizer; all the while, David was blaring the piece of music that would accompany the scene in the finished film, which allowed us to take our camera cues directly from the music."

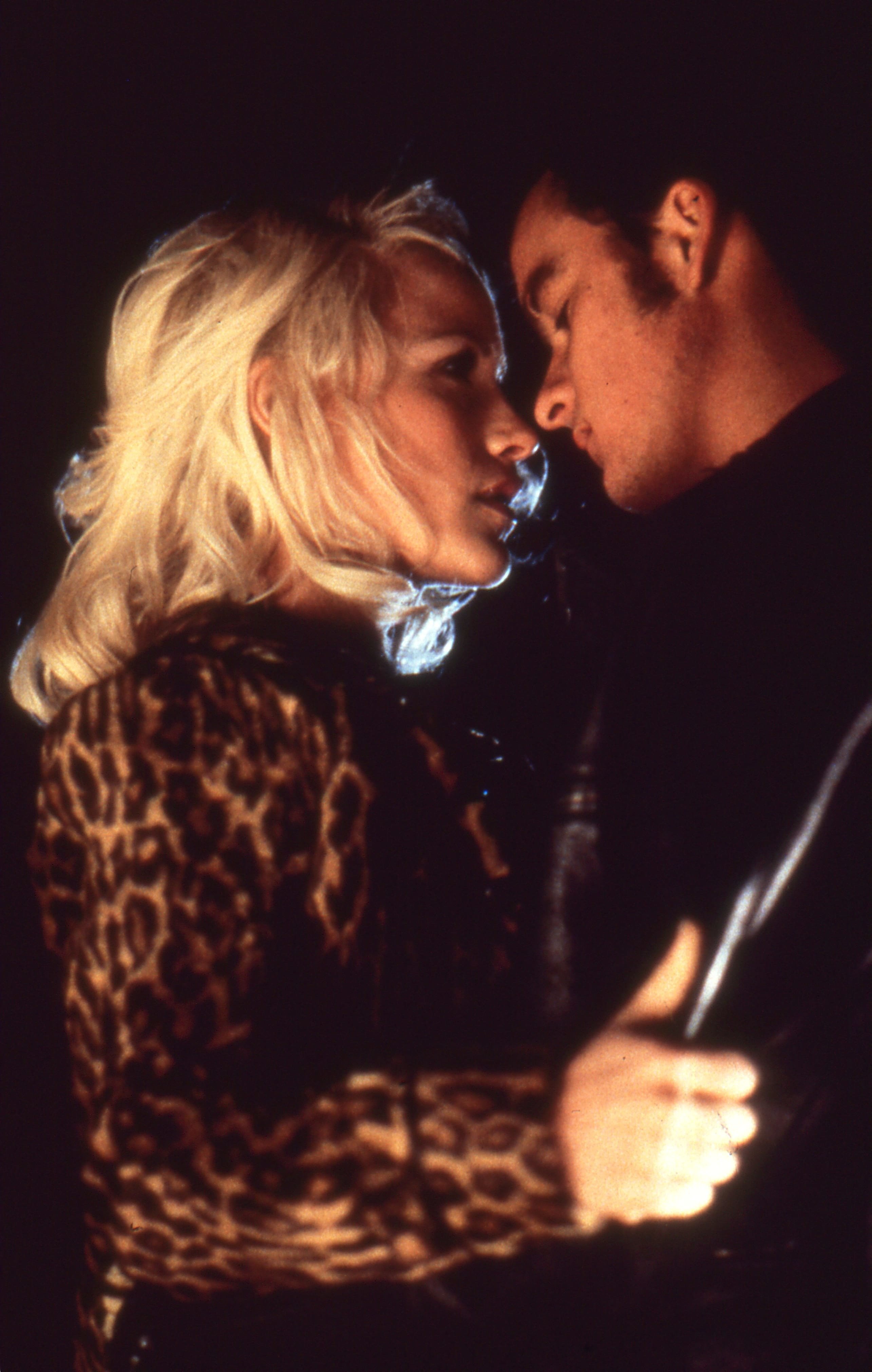

Equally spectacular is a later shot of actors Getty and Arquette engaging in their nocturnal desert love scene, illuminated only by the white-hot headlights of a car. "That situation involved things you're taught never to do — front-lighting and overexposing," says Deming. "When we talked about the love scene in prep, David said he wanted the actors to be glowing. He didn't want to see any details except their eyes, noses, mouths and hair. We lit them with tungsten Pars which were supposed to simulate the headlights of their car, and we overexposed by about six-and-a-half stops. The final effect is very surreal; David knew it was not the 'technically correct' way to do things, but it worked for the movie."

The cinematographer notes that Lynch often comes up with his most inspired cinematic riffs on the set, sometimes while a sequence is being shot. "A lot of ideas would come up on the day of filming, after he'd gotten together with the actors and blocked out the scene," Deming asserts. "There's always a certain amount of logistical preparation, but when you're working with David you have to be ready for anything."

Lynch confirms that he encourages his crews to transcend the technical and logistical tenets of traditional film production. Intent on creating motion pictures with primal impact, he allows his fantasies free reign, and frequently improvises in order to commit them to film. "When you first get an idea, you're imagining it, but eventually you're out there in the real world," the director notes. "There are little holes and blurs in the imagination, and it's not totally complete. But when an actress arrives on the set in her costume, you suddenly have a concrete element, and a whole new bunch of things can happen. You can be painfully aware that something's wrong, and you have to fix it. Or you can be blown away by something odd that happens. The crew might be hanging a lighting fixture that's flopped over and blowing light where it's not supposed to be, but I might see it, grab Pete and say, 'Look at that.' Even if it's not right for the scene we're doing, we sometimes save the idea and use it later. Little things like that always happen, and it's useful to store them away."

“I told Pete to start de-focusing the lens, but he couldn’t get the image as far out of focus as I wanted; he had reached the end of the lens. I said, ‘Well, we’ve got a problem.’ He replied, ‘The only thing we can do is to take the lens out.’ So I said, ‘Okay, take it out.’”

— David Lynch

The director recalls that such a moment arose during the filming of a scene set in Fred Madison's prison cell, just prior to the character's hellish transmutation. "I wanted Fred's face to go completely out of focus," says Lynch. "We had a black screen hanging behind Bill Pullman, and the camera had to be locked off for the scene. I told Pete to start de-focusing the lens, but he couldn't get the image as far out of focus as I wanted; he had reached the end of the lens. I said, 'Well, we've got a problem.' He replied, 'The only thing we can do is to take the lens out.' So I said, 'Okay, take it out.' He popped the lens on and off the camera as we did the shot, and it looked beautiful! We dubbed that technique 'whacking,' and after that I started going a bit whackhappy — but only when it suited the picture."

Surprisingly, Pullman's mind-bending metamorphosis into Getty was not accomplished via computer-generated special effects, but rather with a careful combination of in-camera techniques and cutting-room trickery. The film's editor, Mary Sweeney (who also co-produced Lost Highway), reveals that a makeup effects expert constructed a special "fake Fred head" that was covered with slimy artificial brain matter and then carefully inter-cut with shots of the real Bill Pullman. She explains, "That sequence was completely designed by David, and we constructed it in the editing room, working entirely from elements he had shot on film."

In-camera trickery added adrenaline to other sections of the movie as well. For an operatic shot of a burning shack, the crew deployed four cameras: the Panavision Platinum that served as A-camera throughout production; the Panavision Gold II B-camera; a Mitchell unit owned by Lynch (with a mount that Panavision had converted to accept the company's Primo lenses); and an extra camera body for a Steadicam. The fiery destruction of the ramshackle structure was filmed at four different speeds: 24 fps, 30 fps, 48 fps and in reverse at 96 fps with the Mitchell. "We just turned all of the cameras on and let it rip" Deming recalls. "I think one of the tighter shots done at 48 was later slowed down in post, but the footage in the film is primarily the stuff we shot overcranked in reverse."

Lynch's Mitchell was also used to record the moment when Getty's mechanic first sets eyes on the gangster's buxom girlfriend, who strolls through a garage interior and out into bright sunlight. Once again, the camera's speed control was set to 96 fps. "That shot presented a bit of a problem for me," says Deming, "because when you operate the Mitchell it doesn't unsqueeze the shot, so you're looking at really thin people. To shoot that fast with the filtration we were using I had to go to a higher-speed stock, and I knew that its limited latitude would make the exterior at the end of the shot blow out completely. I talked to David about it, but he just said, 'Great, the dreamier and weirder you can make it look, the better.' As a result, the exterior part of the sequence is white-hot, and I think we even timed it up to be brighter. In addition, the shot we used had a little flicker from the dancing of the light — the camera wasn't a sync model. When I saw the shot in dailies, I said, 'We should redo that,' but David vetoed me again! I told the same thing to the timer, and he said, 'Doing it over would be a big mistake.' He knew that it worked for the picture."

The filmmakers later used undercranked cameras to capture two "superspeed" car chases — one involving the crime kingpin, Mr. Eddy, and a climactic scene in which Fred Madison is tracked across the desert by a fleet of police cars. "For the first chase, we shot all of the stuff with the actors during the show, and then went back on the last day of shooting to get the second-unit footage. We tried a bunch of different speeds — from 20 fps down to six and even four. I didn't want Mary Sweeney to have to go in later, dupe everything and speed it up, because David and I both like to stay away from opticals whenever possible. In fact, most of the film's dissolves and fades are A/B roll and not opticals. It's hard to get people to do that these days, but David appreciates the quality of it, which is really nice for me.

"We did the final chase sequence three times, with two cameras outfitted with different lenses and running at slightly different frame rates — 24 and 12 fps. In this case, some of the footage was sped up and blown up in post, and I think Mary and David also double- and triple-printed parts of it to make the tone more aggressive. While we were shooting that chase, we put Fred's car on a process trailer being towed by a tractor-trailer generator. We had the usual lighting inside the car, which wasn't much — probably Kino Flos. We also set up two carbon-arc lightning machines on scissor arcs, two 4K Xenons aimed into Mylar, two strobes, and a couple of smaller lighting units, like Pars dimming up and down. All of this stuff was working while we were driving down the road at night in the middle of the desert. From a mile away it must have been quite a sight!"

Lynch understands full well that the visceral and often oblique visions presented in Lost Highway may frustrate and even antagonize audiences, but he has often said that he prefers his pictures to remain open to many interpretations. "Stories have tangents; they open up and become different things," the director maintains. "You can still have a structure, but you should leave room to dream. If you stay true to your ideas, filmmaking becomes an inside-out, honest kind of process. And if it's an honest thing for you, there's a chance that people will feel that, even if it's abstract."

Deming later became a member of the ASC and again teamed with Lynch for the feature Mulholland Drive, as well as the third season of Twin Peaks.

The cinematographer has also shot such features as From Hell, The Jacket, Drag Me to Hell, Oz the Great and Powerful and The New Mutants.