Twin Peaks: Dreams, Doubles and Doppelgangers

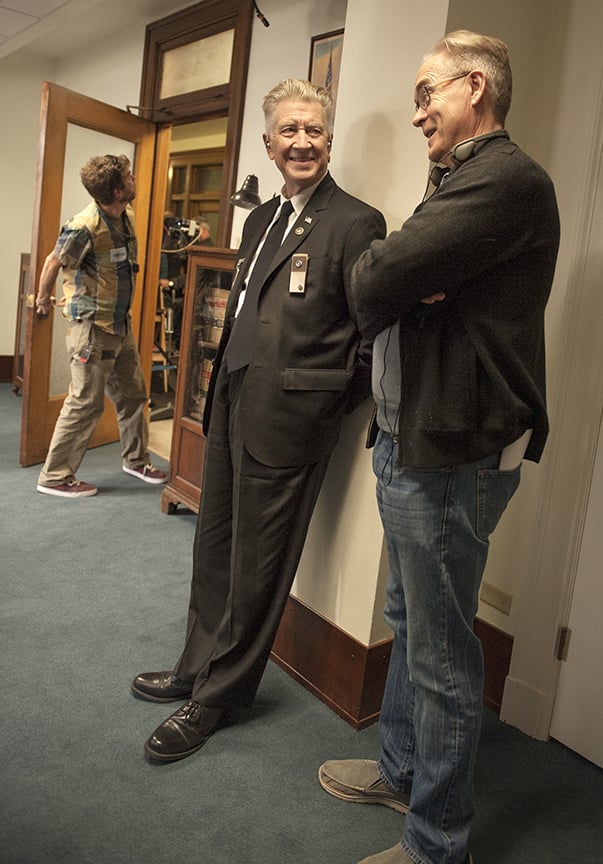

Peter Deming, ASC’s long working relationship with David Lynch reaches a new creative milestone with this perplexing-yet-fascinating revival of the unique series.

Following his previous collaborations with David Lynch on the miniseries Hotel Room and the features Lost Highway (AC March, 1997) and Mulholland Drive, a reasonable person might assume that cinematographer Peter Deming, ASC had a crystal-clear insider’s take on the labyrinthine story depicted in the co-writer and director’s recent 18-episode season of Twin Peaks on Showtime.

But that person would be dead wrong, and the cinematographer even chuckles a bit at the notion: “I think that the man in charge, and the two people who wrote it — David and [series co-creator] Mark Frost spent years doing that — were the only ones really in any sort of command of everything happening.”

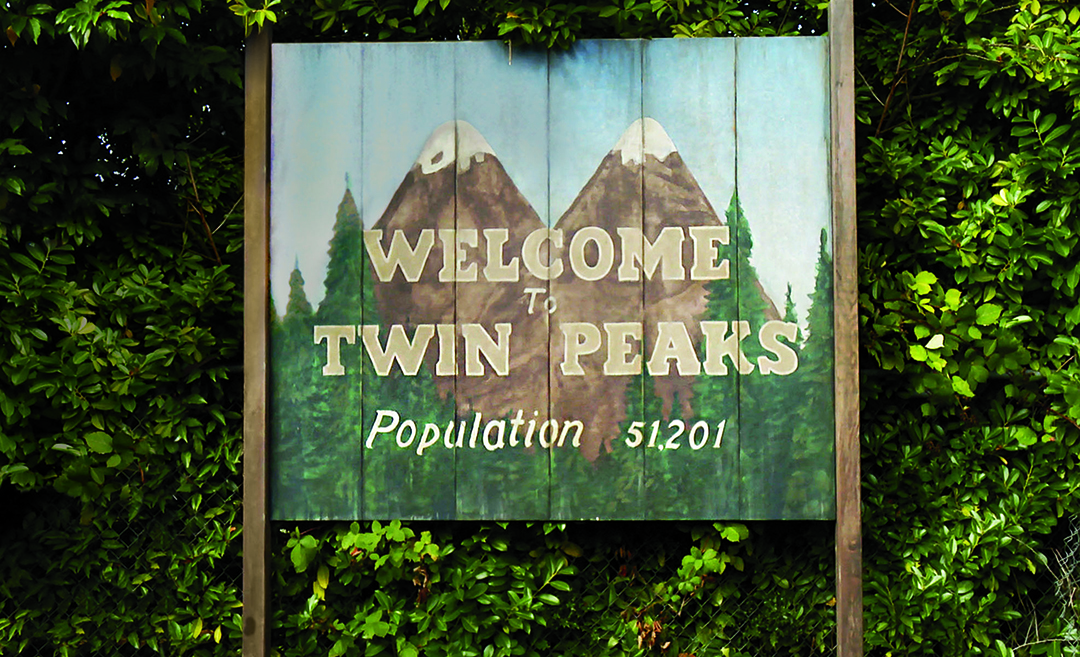

This recent third season of the show — depicting strange, scary and yet sometimes wondrous happenings surrounding the disappearance of FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan), set 27 years after the happenings in the original 1990-’91 series — left many viewers conflicted, yet others pleasantly surprised that Twin Peaks remains as avant-garde and experimental today as it was almost three decades ago.

While curating the ASC’s Instagram account, Deming noted:

“In the fall of 2014, I received a call from David Lynch’s office that he wanted to talk to me about something. He was in Paris, and since I was working in London at the time, I agreed to go meet and learned about the revival of Twin Peaks.Almost a year later we began production outside of Seattle, Washington, with a shooting schedule of 140 days (+1), wrapping in April of 2016. And despite being a ‘series,’ it was conceived and produced as a very, very long feature film working with a script of 525+ pages with one director and one crew.

“In the show, we of course visit some of the locales and classic characters from the original series. David really wanted these to have the same look and feel from seasons 1 and 2 both for familiarity and the small possibility of using some original footage. ‘New’ scenes, characters and situations (and there were plenty) were treated in and of themselves, much as you would in any film. And using black-and-white as a third reality (and my favorite) brought another look into play. I can’t say there was much special treatment given to the small screen as we functioned just as we would with a feature film. And much of the casting in so many of the roles was kept under wraps until those characters showed up on set so that was always a pleasant surprise!”

Deming’s feature credits include My Cousin Vinny, Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery, From Hell, The Cabin in the Woods and Oz the Great and Powerful. He recently completed the forthcoming Marvel superhero feature X-Men: The New Mutants and is currently shooting the period drama Fonzo, depicting the later life of gangster Al Capone, for director Josh Trank.

Here, the cinematographer details his working relationship with Lynch, the task of tackling the 500-plus-page Twin Peaks script, the art of collaboration and the virtue of embracing happy accidents.

American Cinematographer: Let’s discuss the notion of creating what’s essentially an 18-hour movie. From a storytelling perspective, there were things that you were able to do because of the luxury of time — to lavish attention onto the picture and the characters. Does that resonate with you, the idea of being able to tell a story without the constraint of a two-hour capsule?

Peter Deming, ASC: Certainly, but there are multiple stories here. [Laughs] After I read the script, 520-some pages, I certainly remembered the characters and situations from the original show. But then when I got into new ones — and whether they’re doppelgangers, or double doppelgangers, or whatever they are — I was constantly going back and looking at previous pages to piece it all together. I’m not going to pretend that was easy, or even possible, but it certainly was a fascinating journey. [Laughs]

Can you describe the internal reaction you felt when you got to the end of that massive script?

It was a little bit overwhelming, just in terms of all the new things. Certainly, there were the original characters and situations you can picture, and that stuff was much easier to process, I guess would be the word. And then, when you got to the newer ones and try to figure out just the story of those characters, and then, how they work themselves into the story of Twin Peaks, it was… [brief silence] — like I said, [laughs] it’s just so much to — you would need literally a month of living with the script, to absorb it all and be able to say that, “Yes, I’m in command of this story.”

Has that been the experience on the other projects that you’ve done with David Lynch? Because his movies, in some ways, always have something for you to hang your hat on — interesting characters, genre and story elements — but you’re left floating in a lot of other ways, and that’s just the way it is. Is that situation just a different hat for you to wear as the cinematographer, in dealing with a director who’s maybe not quite as literal to reality or to internal logic for the story?

Right, I mean, certainly, the other projects, Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive, there was a clear narrative that might be in two parts, and it might bridge in an unusual way, but those narratives that you’re telling within themselves you totally understand, and you understand the characters and the storytelling. And those creative leaps from there — whether they’re time leaps or whatever they are — you just have faith and believe in the man who’s driving the car. [Laughs] You trust that it’s all gonna work out, because, number one, you don’t have any choice, and number two, history has shown that it works quite well, in fact.

“FBI Cooper obviously has an established lineage, and you know you’re going there.”

In the context of those two features, this is a huge, overarching story of duality and doppelgangers, as you described. How does that lead you in terms of photographing actors playing multiple roles? And specifically in this case, with Kyle MacLachlan playing three roles — Dougie Jones, FBI agent Dale Cooper, and Evil Coop. What was your thought process in approaching each of those characters, in terms of putting them on screen?

FBI Cooper obviously has an established lineage, and you know you’re going there. I think that doppelganger Cooper, or Evil Cooper, or whatever you wanna call him — there’s a strong sense of character there. You just feed off that, and he’s, in some ways, a classic villain, although he does have a certain amount of — well, I won’t say super power — he is certainly a capable person in terms of strength and will and those things. You start from there, and then anything else that David wants to feed into the mix, you feed into the mix. As far as Dougie goes, the approach is driven by his environment and the fact that his part of the story was set Las Vegas — sunny, bright. His manner is slow and so the dramatic pacing changed, certainly in the way we shot it. The character’s relationship to the cinematography is organic: you just take what you can from the characters in the situation, and try to work with that visually. Evil Cooper’s story is, not to be too literal, very dark, and when you can go dark, you do, because that’s how his world exists. [Laughs] And, at some point, you just treat scenes as they come.

Was there a gradual evolution to how you approached each of the characters? Or was it, as you described, basically driven by their circumstance or location?

Yes, driven by circumstance and location, I think so. We tried not to repeat ourselves with any specific visual motifs, unless that was an intended, conscious thing.

As you mentioned before, the most familiar place for us in this new Twin Peaks is essentially anything that actually happens in the town itself, whether it be at the sheriff station, the Great Northern hotel, the Bang Bang Bar, the Double R Diner, et cetera. Was it fairly easy to recreate the look and feel that they established in the original seasons?

Somewhat, I mean, certainly those locations — like the sheriff’s station and the Double R — those are iconic places, so just being there, on that location, you’re halfway home. And then you analyze visually what went on in the original show, and you certainly mix a lot of that in while also trying to make it your own. And then you have to take the situations as they come, in terms of the story. But, certainly, they had a foundation, and that gave us all somewhere to start.

As a viewer, I assume that almost half the look of those environments is just all that wood paneling.

Very much so, yeah, the art direction was a huge factor, and depending on how saturated it was, we didn’t have to do much but light it and make sure people could see it.

Describe a little bit about the collaboration between yourself and production designer Ruth De Jong and the art departments. How did that work out, and how much collaboration were you able to have with them?

I came on to the production much later than everyone else. I don’t exactly know how much later, but [laughs] a little closer to the shooting than I would’ve liked. And a lot of those decisions were created by the original show or by the locations we found. And, obviously, the look of everything is very much a part of David’s imagination when he and Mark wrote the script. He had a specific idea of what these places look like, and he and Ruth, I’m sure, went through all that. And when we could find locations that matched what he thought it would be, that was great. And we would find others that maybe didn’t match David’s ideal as well, and we would have to adjust them, and do a small build or whatever to make them work. And then sometimes you just had to start from scratch.

What were some principal sets that you had to build? I assume that magenta otherworld environment in episode three was a build? Or — correct me if I’m wrong.

Yes, that — I forget what we called the set — but it had a balcony, and as you went into the window, into the room with the fireplace, that was certainly a build. The sheriff’s station was a location, and most of the offices, the conference room, and the bullpen were all practical. But Sheriff Truman’s actual office, because of the scene we had to do there for the last episode, we built as there’s a that crescendo scene that… [laughs]. It gets pretty whacky with effects work we did, and that required us to raise the set so some of it would could be done from under the floor. So, that was a build. And Ben’s office in the Great Northern was a build because either we couldn’t get access to the original or it didn’t exist anymore.

The last episode was pretty spectacular there at the end, in the sheriff’s office, just bringing together all those characters that we’ve gone through so much with. And it was pretty mind-numbing.

[Laughs] Yeah, there are a few of those moments.

In terms of the locations that are new to the series, you couldn’t ask for more disparate choices — between that magenta world, Mr. Todd’s super high-gloss office high above Las Vegas, the suburban tract home of Dougie Jones — but they all have this unique, other-worldliness to them. But you brought a lot of different, starkly contrasting environments to the story.

Definitely, some rooted in reality, and others completely not.

What’s it like working on a project that flips between those two realms so rapidly — between reality and not reality — and having the creative freedom of often not worrying about reality?

[Laughs] Not worrying about reality is the best scenario, in a lot of ways. I mean, because the majority, obviously, of the stories we tell [in movies] are based in reality or some reality that’s been so defined in other movies — like a superhero reality, or a space story reality — that now it has an archetype that isreality for those fantasy worlds. But David’s fantasy worlds are like no other, so you can do what you want in terms of the look, the lighting, and some camera effects. The only disadvantage, I would say, is that David’s the only one who’s living with this reality prior to executing what you have to do to shoot it. So, a lot of [a given scene] you might know a few weeks ahead of time or a week ahead of time, but other things hit him on the day, and he’ll say, “Gee, you know, I wanna take this some other way. What can we do?” Then have to really get the gears going and come up with something. Sometimes we did post-manipulation of the images, for instance, we often used frame-rate manipulation, which I thought was effective. And it’s all experimental. I love doing that stuff; just seeing what happens.

“[David] might say, ‘Oh, I really like this’ or ‘I like that.’ But if you were to directly ask him, ‘Were you happy with what we did?’ [laughs] or, ‘Is that what you had in mind?’ you probably wouldn’t get much of an answer.”

Would you have any idea of how successful he believes he is in being able to get what he has in his head onto the screen, with the help of all of his collaborators?

There’s never a real postmortem with David. He might say, “Oh, I really like this” or “I like that.” But if you were to directly ask him, “Were you happy with what we did?” [laughs] or, “Is that what you had in mind?” you probably wouldn’t get much of an answer. And the process is part of the creativity, so what you come up with is just fine. It’s not like you’re mad, or your hindsight is 20/20 and you wish you had done something else, because being out there and collaborating and coming up with something is for David — I think — part of the joy of making films and making images. It’s all about the process.

What you’re describing is an incredibly healthy approach to creating art, collaborative art, especially.

Absolutely, yes.

As an illustrative point, the visual effects in the show drift between being elaborate and photorealistic and being more abstract and basic. Is there in any way analogous to the lighting or the camerawork? In that sometimes it’s more precise or elaborate, and then other times it’s less perfectly executed?

Lighting wise, it’s all deliberate, and it’s all — I think most of what you’re talking about happens in postproduction and that’s a whole different level of creative process with David, whether he wants it to be realistic — like you say, photorealistic — or he wants it to be more abstract. Some of it feels animated in a rudimentary way. It’s how he feels about it at the time. And maybe he had an image of something much more elaborate when he wrote it, but in the flow of the show — or whatever factors determined — he changes his mind and comes up with something else. When you put all the pieces together and you can watch it, things can happen — but only David and the editors have the luxury to gauge it on that level before we all get to see it.

There was some discussion about shooting Twin Peaks using smaller cameras and having a smaller production footprint, based on his experience of making Inland Empire [2006, shot by Lynch himself with MiniDV Sony DSR-PD150s].

David used a small prosumer camera to shoot Inland Empire and cameras of that size have gotten much better over the years, and people are now shooting with all sorts of things, including iPhones. Honestly, [laughs] if David could’ve, he might’ve shot Twin Peaks on an iPhone. But there was a lot of discussion about shooting with DSLRs, or a Canon C300, or something like that, but a couple factors weighed against that. One was the amount of visual effects that were going to be done for the show. It wasn’t a massive visual effects project, but there were enough. And if you want to make them photoreal and you want them good, you can’t use a rolling shutter camera — that’s just a nightmare for visual effects people. So, that was one factor. And the other was we had to deliver, I think contractually, a native 4K finished product to Showtime, or certainly close to that neighborhood. So we ended up shooting with Arri Amira, which records 3.2K, and then we upresed for the final deliver. Honestly, that resolution, 3.2K, is pretty high-quality. It’s the same sensor as the Alexa; you’re not recording Arriraw, but ProRes. And I’ve seen a few episodes projected and the footage holds up well. So, we gravitated toward that, tested a bunch of cameras, and the Amira would’ve been my choice just given the fact that I had lot of experience with the Alexa, and I thought that its image was the most film-like. After we watched the test footage and talked with our colorist, George Koran, David was in agreement with that, so we went with Arri.

“The collaboration factor is high with David, and if you think of something and you think it could be different or interesting, he wants to hear it, absolutely.”

During those same camera tests, were you also testing lenses at the same time?

I didn’t want to build too many variables into the testing process. And I think that, given David’s desire for — I wouldn’t say rough, but, certainly, he likes digital production very much yet he doesn’t like it to look digital. So, we went with the older Ultra Speeds and Super Speeds from Panavision, which [1st AC] David Eubank spent a lot of time sorting through. And these were not the rehoused “vintage” lenses, but with the original housings, just to give the image a little aberration I guess you’d call it. And I think that worked out quite well.

Tell me a little bit about the creation of this library of LUTs that you and your DIT created for the many different environments of the show.

Maninder “Indy” Saini was our DIT. I’d worked with her in the past, obviously, and the production had budgeted her for eight weeks of work, over the entire shoot, over 24 weeks or whatever it was. Which is insane. I hadn’t shot with the Amira before, so as we were prepping, we found out that you could store LUTs internally in the camera. At the start of the production, I think you could only store 16, and with each build of the software that number grew, but it wasn’t growing fast enough for us. We stored the LUTs on a flash drive as we were importing LUTs, dumping LUTs, so, we devised a plan to just create LUTs just based upon day interior, day exterior, night interior, night exterior, and then build off from those four basic categories, into different levels of saturation, contrast, and green/magenta shifts for mixed-light stations. We also had a black-and-white library of LUTs, which just more or less dealt with contrast and black/highlight levels. So, Indy came out for the first two weeks of shooting, and we created probably 30, 35, 40 LUTs, based upon those four categories. Now, that may sound like a lot, but it’s only 10 for each category, or, like, eight for each category, plus, the black-and-white. So I would work with those while she was gone and manipulate some in the camera, but that was pretty time-consuming to do that, so I mostly stayed away from that. Plus, we would have to then name each LUT and catalog it, so editorial would have it and when the metadata came in with the footage, they had a certain LUT number they would put on that was represented by the metadata. So if they didn’t have the LUT in editorial, it did us no good. So, then Indy would come back — I think she came back, like, six weeks into the shoot, and I had a whole laundry list of stuff [laughter] that I wanted her to do, based upon what we were shooting. Typically, you’d start shooting a scene, you create a LUT, and you’re shooting the scene with that LUT, and the DIT is normally just monitoring it and making sure everything is technically fine. But what Indy was doing was then starting to create these other LUTs, based on the notes that I had, like, “Okay, I need one that with the contrast lifted and there’s green suppression, and it’s a 30 percent DSAT,” and all these things. So, she was busy creating these LUTs, based upon what I’d learned while she was gone. By the end of the show, I think we had close to 120 LUTs, which is not that many. We had the four categories, so maybe 20-25 LUTs for each, plus the black-and-whites. The camera could store 20 or 25 by then, but we still had to delete and add from the flash drive. I’d just put the flash drive in the camera and toggle through the LUTs until we decided which ones we needed for the next day or two. What’s really interesting, from having shot so many projects on film for years and years, is that we would light the scene for film, shoot it, and you had a specific idea what you wanted that scene to look like. You’d call the timer at the lab and say, “Okay, this is what I’m going for.” And maybe you had a visual reference; maybe you just did it verbally. And the color timer would interpret that, and I would say five times out of 10, depending on your relationship with the color timer, it would come back looking like what you wanted it to look like. Maybe it was off a little bit, maybe it was off a lot. Then sometimes you’d get back film dailies that were off a lot, and say, “Well, that’s not what I wanted at all, but I kind of like it. It’s interesting.” So, what having all these LUTs stored in the camera created that dynamic again when you would light the scene and set the camera and say, “Okay, what LUT are we going for? Which one are we gonna apply?” You’d toggle through the LUTs looking for the ones you think might work while looking at the monitor, I’d have an idea of two or three or four that I thought would fit the particular situation, the scene we were shooting. And as you’d toggle through the camera, and you’d have to go through ones that you didn’t think you wanted, but you’d have to see them anyway, because you’re toggling through, and you’d suddenly say, “Wow, that’s pretty interesting, you know, let’s not forget about that.” Often, I’d pick something that was completely out of left field, because I’d show it David and I’d say, “I was thinking this, but then that LUT came along. What do you think of it?” And he was, like, “Yeah, I like that better.” So there was sort of the happy accident that used to come through the lab and the color timer in shooting on film negative that was being reintroduced into the creative process on set. But now you have total control over it, because it’s digital, and you have a set of zeroes and ones that now you’re going to give to editorial and they’re gonna put that LUT on. When it came time to color correct the whole show, Foto-Kem went back, obviously, to all the LUTs that we had, and put them on once everything was conformed. And sure, scenes bounce around and things like that, but the foundation of what we did on-set was there, and it’s exactly what you did on the day. Now, maybe you keep it, maybe you don’t; that’s just part of the creative process that’s always happened, whether it’s film or digital. But I found that process of going through a library, a catalog, of LUTs to be eye-opening, and I wish I had the preparation on every project, to load in 50 LUTs and say, “Wow, what does that look like?” And not be so set in our way of how you want something to look, and be more free.

I would imagine that that’s certainly a consequence of working with David Lynch. Or is it?

No, I mean, the collaboration factor is high with David, and if you think of something and you think it could be different or interesting, he wants to see it or hear it, absolutely.

As you were describing the notion of toggling through LUTs and maybe picking something that wasn’t expected, the first thing that popped into my mind — and it’s a small scene between Gordon [David Lynch] and Albert [Miguel Ferrer]. They’re having a heart-to-heart…

Yes, outside the airport.

And the image is this icy-blue that’s completely different from anything else in the show. Was that one of those happy accidents?

Well, that scene, I have to say, wasn’t that icy-blue when we shot it, and this is something that I think came to David in post. There are a small number of scenes like that, maybe where there was a hint of something, and he decided to run with it. You know, the lavender peach world of Cooper’s dream certainly was part of that kind of experimentation. And that’s another reason why David embraced digital so quickly — the number of paintbrushes you have in the different chains of the process was intriguing to him. And to be able to keep creating to the bitter end is very attractive. I think that the scene with Gordon and Albert — I don’t know the creative behind David’s decision for that scene, but I do know that between the time we shot the show and when it aired, Miguel passed away, and I think that was very emotional for David as they were friends and collaborators for a very long time. So the look of the scene may have been driven in part by that, and partly by story, I don’t know — I haven’t specifically asked David about it. But that certainly might be part of it. [Ferrer died on January 19, 2017, some four months before the show premiered.]

That’s an interesting read on it. And, as a longtime fan of the show, Catherine Coulson’s passing [on September 28, 2015] also added an incredible sadness to her scenes.

Yes, and there’s a shot of the sheriff station, just an establishing shot outside, that connects with that. I actually posted it on Instagram awhile back [while curating the ASC’s account]. In the trees above the station, you can see the sun coming through, and these orange beams in the mist of the morning. I remember that we arrived to the location very early that day and we were setting up the shot, and I said, “Oh, we gotta shoot that before we lose it. It’s so cool.”

And after the first couple of takes, we got the call right on the set — I don’t know who it was, David or a producer — and we got the news about Catherine. And we all just looked at each other and then looked at this light that was happening as the sun came up, and it was a pretty amazing moment. So, that was something.We knew of her condition, and we knew it might happen anytime, but when you actually hear it, it’s difficult. But she seemed to be speaking to us at that moment.

I can’t imagine. Tell me a little bit about the black-and-white LUTs you came up with. Did you have variations on it? Or was it consistent throughout all the black-and-white portions of the show?

No, we definitely had variations, basically black-level contrast variations and specific levels of highlights and, separately, shadow detail. There was a LUT, like, if we were trying to do something in available light, late-day, where we needed the gamma up a little bit, and — but that was about it. I don’t think there were more than 8 or 10 [laughter] LUTs in the black-and-white world, but they were all useful.

How do you feel the Amira works as a black-and-white camera? Was that one of the particular tests that you put it through, initially?

No, not really. I had done black-and-white with the Alexa and the Red, and any time you do that, certainly you drain all the color out and start working with contrast. What it doesn’t have is that silvery quality that black-and-white film has. Now, Red makes a monochrome camera, which I have heard has a little bit of that quality. I’ve never used it, I’ve never tested it, but I’d be curious to try it. I know David Fincher was high on it when he tried it. But I think all the digital cameras all do a pretty good job, because you have so much control over those other things that make black-and-white great, which is contrast, and black level and midtones. Now, you can also play with the color contrast underneath the desaturated black-and-white image and do all sorts of things with that, which you can’t do with black-and-white film — outside of filtration — or, presumably, with the monochrome camera, I don’t know. And it’s funny because the simple filters on some of the phone apps can do the same thing. Like, for instance, Instagram, you go black-and-white, and then you can play with the tint/color contrast underneath the black-and-white image, and it does amazing things. The amount of control you have in the digital world over a black-and-white image, is pretty astounding.

When I think of the black-and-white portions of the show, I immediately go to episode 8 and this — after we pass through the thermonuclear cloud and end up at the gas station. Describe to me a little bit about shooting that sequence, in creating those pieces for that sequence, and how was it presented to you. What’s that process like, of creating something that is so abstract? And it’s so far away from narrative film — can you describe that process at all? I’m sorry, it’s a little hard for me to…

No, I understand. [Laughs] I understand what you’re saying. I mean, the gas station was very abstract. we did a lot of things with very rough camera movement and speed manipulation which David certainly amped up in the post process. And in terms of the fireman’s house by the sea, and, particularly those scenes, I think that the design of it, you know, the design of the set pieces, the carpeting, all that, David is very involved with. Once you get there, you’re like, “Okay, [laughs] this is not some place I’ve been before.” So you want to bring out the factors, from a lighting perspective, that you react to on initial contact, and some things you want keep subdued, to create a little mystery around. And it’s finding that balance of things you can see, things you don’t, things you think you can see, and things you just hint at. Particularly when they get into the big room, there were things we wanted to see, things we didn’t want to see. And that’s the challenge of it. The logic of the real world — you just throw it out, and you become more impressionistic, more theatrical. And it’s whatever you want do to make a provocative image. You can do it because no one who’s watching this has even been to this place before, so, no one’s gonna raise their hand and say, “Hey, that’s not supposed to look like that.” Because this is new, it’s totally different, and, whereas, for instance, when you go into the scene in the radio station. A lot of that look is based on reality. It might be a little stylized, but it’s a radio station in a certain time period. Not everyone’s been there, but they can imagine it, they’ve seen historical visual references — not that we had to adhere to that at all… So, that’s a different creative process. And a lot of it is driven by the script, and what the action is, and what things you need to highlight.

What you’re describing is one of the reasons why the show is so intriguing — that amalgamation of the incredibly familiar and often nostalgic amidst the new or unexpected.

Right, and I think that since the beginning that has always been part of David’s work. I mean, whether it’s the underbelly of the small town in Blue Velvet, or certainly the world of Eraserhead has all those familiar settings. But these characters and those things that happened [laughs] are not things you’ve experienced before, and you’re rooted in a certain amount of reality, to give it that familiarity, but that’s where it ends.

“Honestly, there were a few days where we didn’t know if we were making Twin Peaks or we were IN Twin Peaks.”

Can you describe the lighting setup in the red room, was it just kind a standard studio-type setup, with a grid overhead and just soft light?

It was very much that. [Gaffer] Michael LaViolette created a big, double-diffused soft box source overhead, and [key grip] Paul Wilkowsky also built a large light-controlling eggcrate similar to what you would normally put on smaller lights. The soft box and its eggcrate were as big the room was — 40’ by 40’, or something like that. So with this eggcrate covering a huge soft source overhead, we could lighten and darken certain areas because we never knew what sort of set pieces were going to come in, or if we had to effect exposure in certain parts of the room and sometimes the shots were so wide that we couldn’t get anything in above the frame to control things. So, there was that aspect of it, but David wanted it — we actually talked a lot about the red room, because the TV show [shot by Ron Garcia, ASC and Frank Byers, ASC] had one look and [the prequel feature film] Fire Walk With Me [shot by Garcia] had a different look. Some of that was by design, some of it was… you know, maybe the red drapes were different than the last time. [Laughs] So, this time out, David wanted the red room to be the most high-key thing in the whole show. There’s enough in the oddball content along the way to make it other-worldly, so we didn’t have to add to that with the lighting here.

To make this strange and creepy place so high-key is completely against expectation, as well.

Right, it’s definitely against the grain and against type.

Did you have problems in there, because of the red drapes, with skin tones? Or was it just not an issue?

No, the red drapes, for the most part, really soak up a lot of light; they don’t bounce much. And no one is, you know, except for when they’re moving through the various doorways, they’re not living too close to those drapes, so that didn’t factor in.

What was the most unexpected aspect of the shoot or the most challenging?

Well, it was not unexpected because of the length of the script, but there was a longevity to the shooting that I think for most of us was unprecedented. And some of the people on the crew I’ve been working with for 30 years — anywhere from 15 to 30 years — and they have all very extensive production experience. And we’ve done little movies and big movies, and the big movies sometimes had nice long schedules, but this one was beyond comprehension. I mean, we started shooting right after Labor Day, September of 2015, and we wrapped the middle of April of 2016. When we started, we couldn’t even think about the end; we had to just get to Christmas. So that was one film, and then after Christmas was another film. [Laughs] You know, 141 shooting days, so… it sounds like, “Oh, it’s just a long shoot,” but there’s this psychological gearing up for this marathon that — honestly, there were a few days where we didn’t know if we were making Twin Peaks or we were IN Twin Peaks. Because some days just got so bizarre, we’d look at each other and say, “What’s going on?” And I will say, those few days, [laughs] whatever was going on made its way into the camera and on screen, so that was good.

Is there any particular scene you could point out where you felt that was a benefit?

Well, it’s always a benefit with David. [Laughs] It’s getting unhinged in a weird way. There were some scenes up in the woods, you know, the Sherriff Truman and the others were walking around and finding…

Oh, when they go to the Jack Rabbit Cathedral?

Right, and then this vortex opens up. That was one of those days… and this is purely subjective; I wouldn’t say that everyone [laughs] felt that way. And another was maybe when the FBI — Gordon, Albert, and Tammy [Chrysta Bell] — take William Hastings [Matthew Lillard] out to that house where he’d seen Phillip Jeffries. That scene, shot over two days, that was pretty unusual. And then, of course the scene in the sheriff station at the end, which was just as weird to shoot as it looked in the show. Maybe more so as we spent 12 hours shooting it. [Laughter]

The first scene you mention, in the woods, has such beautiful natural lighting, and I was impressed on how the Amira handled the highlights and shadows in the forest.

Yeah, and the interesting thing about that scene is that it was that the set took a little time to make correct on the day, and then we got up against the end of the day with about three hours of daylight left. Much of the lighting we did out in the forest like that is just to work on the contrast — make sure the highlights don’t blow out and the shadows don’t get swallowed up. That’s all you’re doing. Then, at a certain point in the day, it started to get dark, or darker, and the lighting started to be noticeable, you know? And we kept adjusting to try to keep it looking “natural,” but at a certain point the light dips enough that you’re going to lose that battle. And in this scene there’s this naked woman on the ground and a gold pond and there’s smoke and lightening, and it’s taking on this surreal feeling because the ‘natural’ lighting you’re doing is now becoming more active. And while we at first started to suppress that a little bit, we then just started to go with it, because it was just so unusual. We literally had just a 20-minute window to get that feeling and then we’d be out of daylight. So, I had a 30-second discussion with David about it. And, as usual, we just went with it, because it was unexpected and spectacular. And that’s when we asked ourselves, “Okay, is this reality or is this Twin Peaks?” [Laughs] Because

“I’ve known David for more than 25 years, and there’s no other director I’ve worked with who is so constantly the recipient of the happy accident.”

That clearly it speaks to the level of the collaboration, in that you’re able to do things on the fly like that and make it seem completely intentional. Because it is a result of the established process to embrace the unusual.

I’ve known David for more than 25 years, and there’s no other director I’ve worked with who is so constantly the recipient of the happy accident. There’s a number of projects, smaller projects, that we’ve done over the years, where you have the same elements you do on any shoot, but then something weird happens, and you look at each other and just say, “Quick, turn the camera on.” [Laughs] There’s something about David’s process and presence that makes those things happen, I’m convinced of that. I don’t think it’s by accident. You can’t make that happen. They just — it’s just weird. I don’t know what to say. There’s clearly a higher power at work here. [Laughs]

Well, what you’re describing can’t just be luck, but part of a creative process that invites or welcomes happy accidents. As opposed to deeming things that are contrary to the initial visual concept to be a problem to be dealt with.

I think it’s both. I agree with you, I think it’s an attitude to accept whatever happens, and embrace it and build on it. And a little bit is luck, because the few people who have been with me on this whole journey, who have been working with David forever — we just shake our heads and say, “How does he do it?” Because we’ve tried to do it in other situations with other people, and it just never works. And then, somehow, it just happens. I don’t know how. But part of it is creating an environment and a level of comfort in the crew that they just say, “Oh, try this,” because they know they’re not going to get yelled at for it.

People who have difficulty with David Lynch’s work are often trying to be too literal or logical about it.

Right. Well, because part of it is that David does give you “literal,” to a certain extent. But he doesn’t stick with that. He deviates. And that’s what you need to be open to. I think the original show obviously stuck to a more literal narrative than this one did. Certain people were expecting that, and they got a lot of it, but they also got a lot more. They got a lot of unusual stuff that the fans who are maybe more open-minded embrace more than do some other people.

Were you involved in the Blu-ray mastering of the show?

Not directly. I’m sure they just took what we timed for Showtime, because that was the essentially a Blu-ray master. For the few times the show has been projected theatrically — I think the first two episodes, mostly — they made a DCP. Normally, it’s the other way around: You make a full DCP and then you go back to make a Blu-ray master. But, essentially, what we made for Showtime for broadcast was the Blu-ray.

What was your experience as a viewer of the show after going through this odyssey of shooting it?

That’s an interesting question, because I’ve only watched it through once, as it was aired, and I feel like I’d have to watch it again to really watch it. I saw it 13 months after we finished shooting. So, some of the stuff I was watching, I’m a year-and-a-half removed from, and, to a certain extent, it was a memory lane, you know? I’m watching the show and it’s, like, “Oh, yeah, I remember that scene.” And then all these personal experiences come back to me. So, 15 percent of my brain was distracted by the experience of making it. I feel like now that I’ve gone through the show once, that I need to go back and watch it again, and try to figure it out more for myself.