Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC: Cinematic Rhythms

Honored with the ASC’s International Award, the cinematographer reflects on his career and collaborative process.

Standing on a suburban street outside the Cinéma Normandy à Vaucresson, surrounded by French police, 11-year-old future ASC and AFC member Darius Khondji started to cry. His mother, Suzanne, and older sister, Christine, had dressed him up to help him look old enough to see King Kong — admittance was denied to anyone under 13 — but their disguise was quickly exposed and he was escorted out of the theater as the opening credits began. “It was a sad moment, but very beautiful, because I saw those opening credits,” Khondji recalls with a laugh. He didn’t know what a cinematographer was, he adds, “but I started to pick up the names of the crew in the credits. For me, it was a determinant point.”

Long before his formal education or professional career began, it was moments like this, Khondji says, that made him want to be a director of photography — “drop by drop by drop.” He discovered his love of cinema in his childhood home in the suburbs of Paris — what he describes as “like a small, scary, Baroque castle, with a pointed roof and a cross at the top” — first watching the 8mm reels of vampire movies his older brother, James, managed to find for him, and then filming his own horror shorts with an 8mm camera he purchased with some pocket money.

“My first films were for fun, but I was taking myself very seriously,” Khondji recalls. “When I was 11, I’d dress up like Dracula … I thought I was Dracula. And I started out by asking a friend to film me — but it soon became rare that I would appear in my films, because I realized that I wanted to hold the camera all the time. These were the signs that I was after something visual: the look, the point of view, the atmosphere.”

Khondji’s early moviegoing days were punctuated by what he calls “visual shocks”: films like Citizen Kane and The Conformist that, even as he was too young to fully grasp their narratives, played like “photographic fireworks,” and seemed to him as if “made by giants.” By the time he was studying at New York University in the mid-’70s, he had come to regard these films as “the early triggers that influenced me later in life. I realized, little by little, that I had opened my eyes, heart and soul to movies. Then, when I took a screenwriting class at NYU, we had to visualize a scene from a book by William Faulkner, Light in August, and I successfully created the blocking for the scene. That was just as important because I realized, ‘I can do this!’ I started to want it. And, as with all else in life: Desire triggers everything.”

Fresh out of college in the early ’80s, Khondji returned to France, completed training at the Laboratories Éclair (now known simply as Éclair), and found work as a camera assistant — first for experimental filmmaker Marguerite Duras, and subsequently for cinematographer Bruno Nuytten, AFC and “a little for Eduardo Serra [ASC, AFC] and Pascal Marti [AFC].” On the side, he continued making shorts of his own, but did not make the leap to feature production without some urging from his mentors. “I made two or three short films, and I started to feel the real pleasure of working with directors and actors. I showed those films to Bruno and Eduardo, and they said, ‘Come on, Darius — you know everything you need to know now.’ They were very encouraging and pushed me to start shooting.”

Golden Touch

Khondji’s first feature as director of photography, Embrasse-moi, was “a nice way to break the ice,” he says, but after the film was finished, he was left with the feeling that “I was not yet free to express myself in a way that would help the director.” Once he met filmmakers Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro, all that changed.

“Jean-Pierre and Marc had written what would be their first feature — Delicatessen — and they were looking for a cinematographer,” Khondji recalls. “They had seen two short films I shot: One was filmed in a boxing ring in 1.33:1, color, 35mm; the other was a music video for a popular French singer, Alain Souchon, that became a big hit. We met, we got along — and not until then did they realize that I had shot both of those films! So, they asked me to make their film. We were young and excited about working together because we were striving for visuals that, for 1991, were quite special and striking.”

Delicatessen is set in a post-apocalyptic wasteland — which, Jeunet says, made him all the more surprised by Khondji’s approach to creating the film’s palette. “Marc and I were stunned: We couldn’t have possibly imagined a film so gold! When we shot it, we were envisioning shades of blue, dark green … but when we filmed a scene on a rooftop, Darius said, ‘Maybe we should commit to gold instead.’ I was a little thrown off, but he was right! It was very original.”

To some degree, this hot-baked aesthetic was Khondji’s rejection of a predominant trend in French cinema at the time — one that the cinematographer says “often depicted dawn and dusk in an aura of blue.” But the golden glow that envelops Delicatessen was also the culmination of Khondji’s ongoing experiments with a technique he had honed at Éclair, and in his own short films. “I love blacks, and I love to pull the color out of the image. So, controlling the color became a big thing for me. But early in my career, there was no DI and we couldn’t manipulate color that way. Inspired by the color processes used by Roger Deakins [ASC, BSC] on 1984, Pasqualino De Santis on A Special Day, and Vittorio Storaro [ASC, AIC] on Last Tango in Paris, I decided to separate and subtract color in Delicatessen with a bleach-bypass process. By skipping the bleach stage of printing, we could leave the silver on the positive — so that the light wouldn’t go through the print, and we could get high contrast between our golds and those very strong, inky blacks.”

The filmmakers relied on a variation of this color process when making their next feature — the 1995 fantasy The City of Lost Children — this time amping up contrast between Khondji’s preferred pitch blacks and Caro’s desired use of green. Khondji notes that by this time, his joint ventures with Jeunet and Caro had allowed him to achieve what he sought after most in his early years: “the degradation and manipulation of the image. And when David Fincher called and asked me to do Seven [AC Oct. ’95], it was because he wanted to implement a process that would do that as well. I was able to use color process as a tool — making it different as I moved from one story and one director to another — and it’s what led me to make my first movie in America.”

America to Europe and Back Again

Once hired to shoot Seven — the brooding serial-killer thriller that would make him a known quantity in Hollywood — Khondji began planning how he would adapt his color process to fit Fincher’s vision. “David was after an image that was dark, darker and darker still. Very black — but distinctive enough to be able to see the detail within the black. We loved the noir films of the ’40s and ’50s, but that kind of photography had only been achieved in black and white — never in color. In most films shot in color, the image was flatter, softer, more diluted.”

To solve this problem, Khondji worked closely with Beverly Wood, ASC associate and former vice president of technical services at Deluxe Laboratories, implementing — for the first time on a feature — the company’s newly developed silver-retention process, Color Contrast Enhancement. “CCE was a more radical bleach-bypass process than any I had used before,” Khondji says. “It allowed us to subtract lots of color from the image, which we could then add later through elements like set and costume design.”

After completing Seven, Khondji photographed his next two features during a two-year span, partnering with Bernardo Bertolucci to make Stealing Beauty (AC June ’96), and then with Alan Parker to make Evita (AC Jan. ’97), the musical biopic centered on the life of Argentine icon Eva Perón (Madonna) which earned the cinematographer his first Academy Award nomination.

“Bernardo Bertolucci couldn’t care less about what I was doing with David Fincher,” Khondji says. “[Unlike] Seven, for Stealing Beauty, set in Tuscany, we didn’t want to subtract so much color. We just wanted to stylize the image with some color in certain areas and less color in other areas. So, we used the color process of Technicolor’s ENR, which gave us quite strong, distinctive blacks, but allowed much more light to go through the silver.”

With Evita, Khondji says that Parker was after “a completely different world of imagery” — not only with respect to its color process, but through the way in which the film marries multiple shots together much like a music-video montage, at times altogether eschewing narrative linearity. “We took each scene of Evita — a scene with tango dancing, a scene in which Eva delivers a political speech, and so on — one at a time, and each moment of Eva’s life would have a different tempo and different lighting that would correspond to different music. With each scene, we were in front of it, approaching it as one thing, by itself — aware that there might not be any continuity between what we’re shooting now and what we’ll shoot next. I had one of the best experiences of my life making Evita, because shifting the light and color according to a different scheme or emotion within a scene — not beholden to continuity — gives you a lot of freedom.”

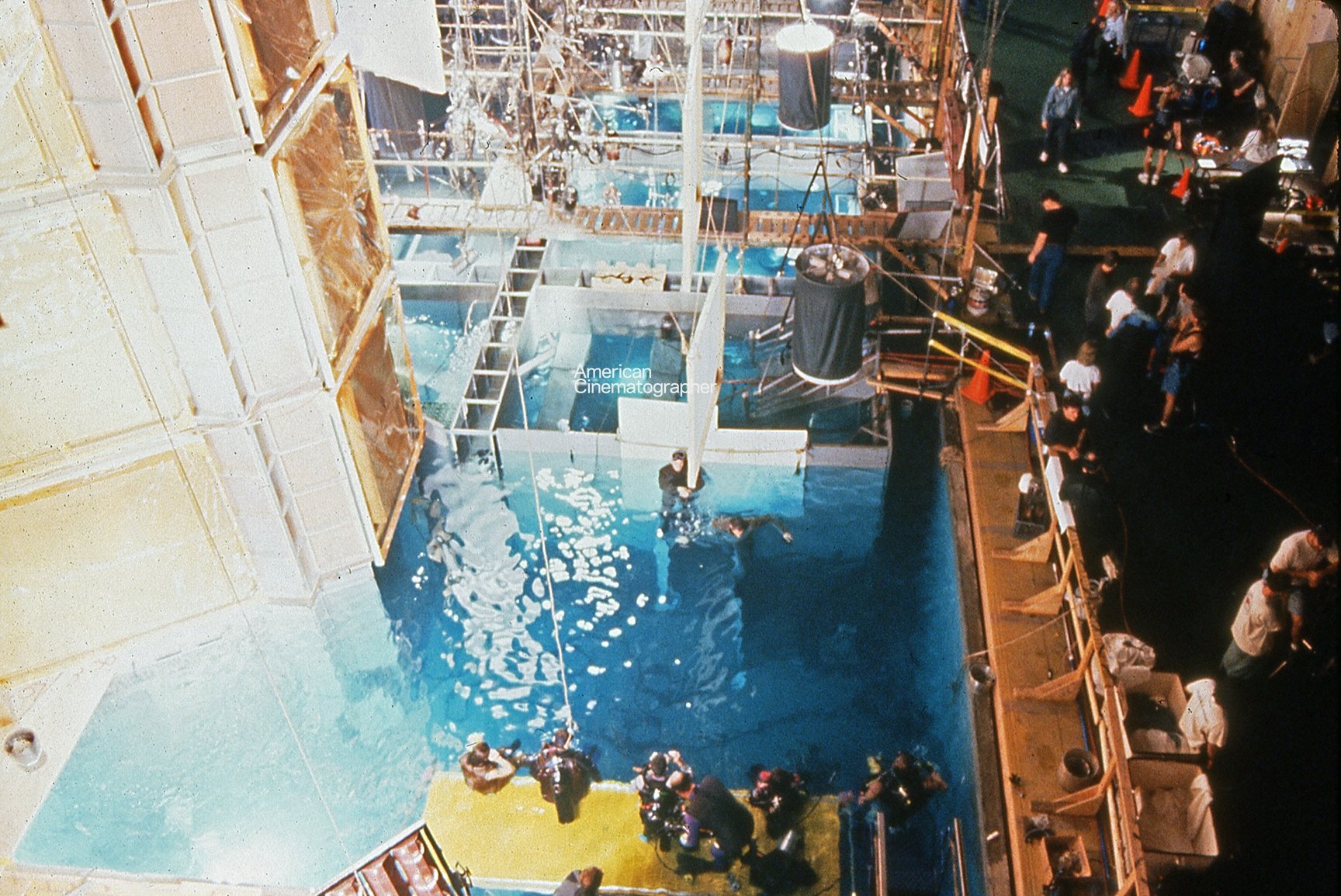

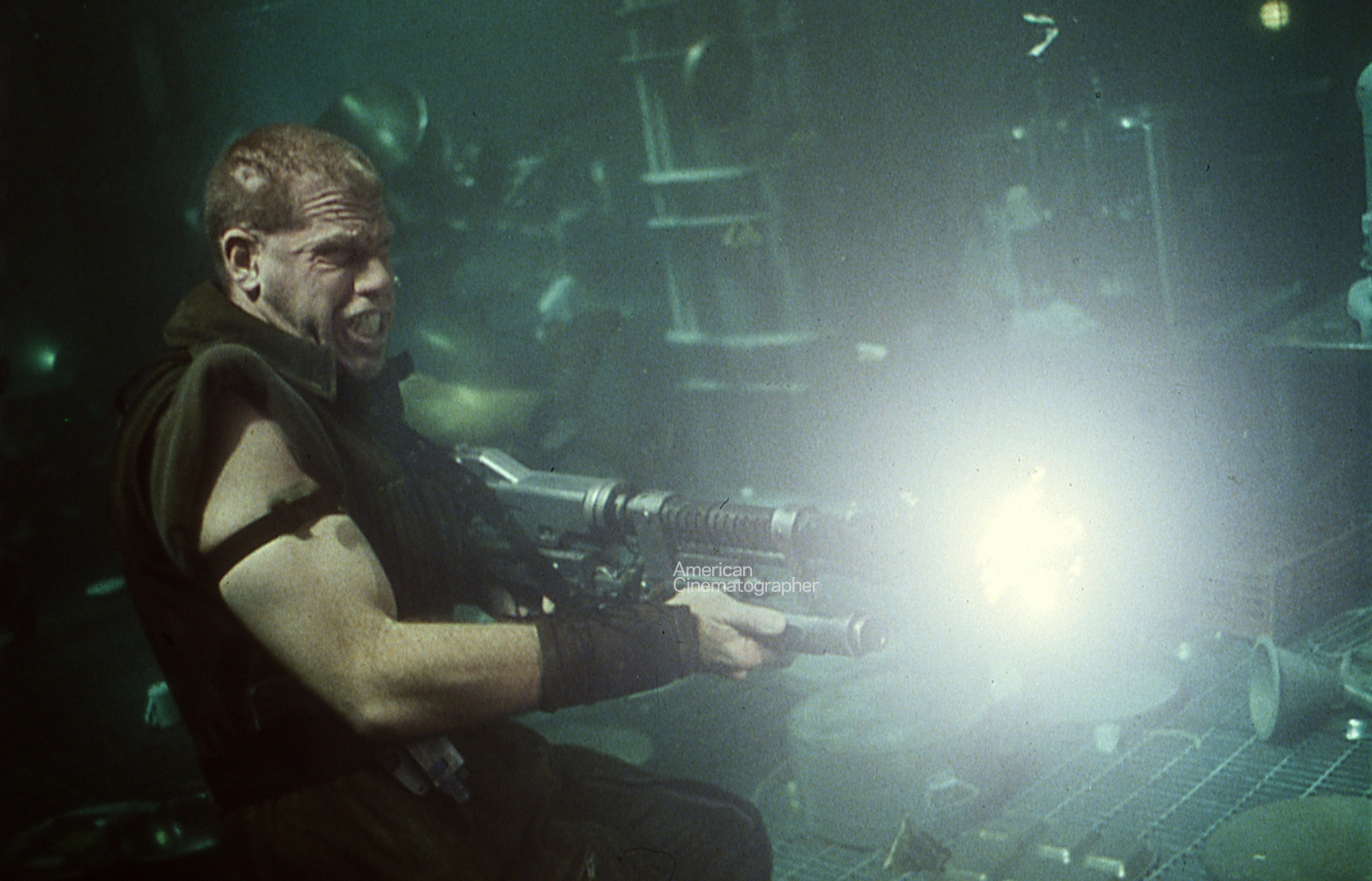

After Evita, Khondji yearned to make a science-fiction film, and was able to bring one to fruition in 1997, when he reunited with Jeunet to shoot Alien: Resurrection (AC Nov. ’97) — the pair’s first and only Stateside collaboration. Jeunet is quick to note that the film’s underwater sequence was the most challenging the two accomplished together, as well as his favorite: “It’s a beautiful scene, with long, slow, complicated camera movement. Darius was wearing a mask and an oxygen tank while filming the divers, who were our stunt doubles, and it was impossible for the two of us to communicate.”

The crew filmed “in a gigantic tank at Fox Studios,” says Khondji, who operated B camera alongside underwater expert Pete Romano, ASC. The cinematographer recalls with a laugh, “Jean-Pierre was just yelling commands from above the surface of the water. We had to interpret those and respond to them with sign language. But I love the look of the scene, and how we mixed the creature effects with the underwater atmosphere. In the end, it’s also one of my favorites.”

“Becoming the Director”

From the aughts through the present day, Khondji has shared sets with some of the most singular directors in modern history: Danny Boyle, James Gray, Michael Haneke, Alejandro González Iñárritu, Bong Joon-ho, Sydney Pollack, Wong Kar-wai, Nicolas Winding Refn, and Josh and Benny Safdie. If there’s any explanation for why he’s been so sought after by such an eclectic array of artists, the cinematographer believes it’s because he’s good at being a chameleon. “I don’t see what my style is,” Khondji says. “I don’t have a style. People will tell me, ‘Your style is to do this and that,’ and I’ll say, ‘Okay, I recognize those things.’ But to me, none of what they point out is a ‘style.’ If I do have a style, it is to want to enter the head and heart of the director. It’s about becoming the director — helping them create their world.”

Gray — who collaborated with Khondji on the features The Immigrant (AC Jun. ’14), The Lost City of Z (AC May ’17) and Armageddon Time (AC Jan. ’23) — stresses that this intimate approach to collaboration is deeply rooted in personal friendship. “During a shoot, he comes over for dinner all the time,” Gray says. “By the time we started shooting The Immigrant, we had talked so much about our tastes that we achieved a shorthand very quickly, and it’s never really changed since then. On set, we complete each other’s sentences and he doesn’t need to hear a lot from me. We see things the same way, and it’s a rewarding thing to be able to work with someone who shares your mindset.”

For Refn, who enlisted Khondji to shoot seven episodes of the languid and lurid crime miniseries Too Old to Die Young, the joy of their collaboration came from “Darius’ ability to adapt on the project’s terms. The combination of him and me was so abnormal because we came from two different worlds — and yet, when we first met, we bonded over our love of our iPhones and suddenly we had a lot to talk about.”

During production, Refn discovered that both he and Khondji “have a love for symmetrical framing — a natural obsession with the corners of the frame, and how our use of zooms could extend each frame’s symmetrical design.” Due to his color blindness, Refn also tends to favor neon-noir aesthetics — which, he says, allow him to better perceive and control the image — and Khondji embraced this idiosyncratic style: “When I learned that he was color blind, I said, ‘Okay, Nicolas, I’m going to photograph this show for you. Not for anyone else — not even the audience.’ So, when people watch Too Old to Die Young, that’s what they are seeing: how he sees color.”

Bong, who first worked with Khondji on the sci-fi fantasy Okja, says their bond was forged on a location scout in the Korean countryside. “Darius is like a passionate explorer. There was a location in the deep mountains, and the only way to get to it was by climbing a rope. It was very steep, but we went up there together — he didn’t hesitate. Early on, there was already a strong kinship, and that’s what I remember most: climbing up that rope together to get to the mossy waterfall.”

When Iñárritu tapped Khondji to shoot his autobiographical surrealist dramedy, Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths (AC Dec. ’22), he knew that few other cinematographers would resonate with such a personal project. “The film is radical and breaks with convention,” says Iñárritu, “but Darius understood my conception from our very first phone call.” That phone call, Khondji says, “immediately became very deep — this man was so revealing about himself, his family and the things that are important to him. He was setting the tone, like one does before playing a musical piece. He wanted the film to explore different states of consciousness, and we knew there would be many technical challenges in order for us to achieve that. But more important than that, we had to be a match.”

Reflecting on each of these relationships, Khondji stresses that “it’s important to understand that I didn’t start out the way that I am now. I started as someone who wanted to make beautiful images for beautiful films — but that’s no longer the reason I make films. The reason I make films is because a director excites me. If a director does not trigger my excitement, I cannot help them. I need it to be a love affair.”

Discoveries and Rhythms

In order to not repeat oneself, Khondji says, a cinematographer must remain intent on making new discoveries.

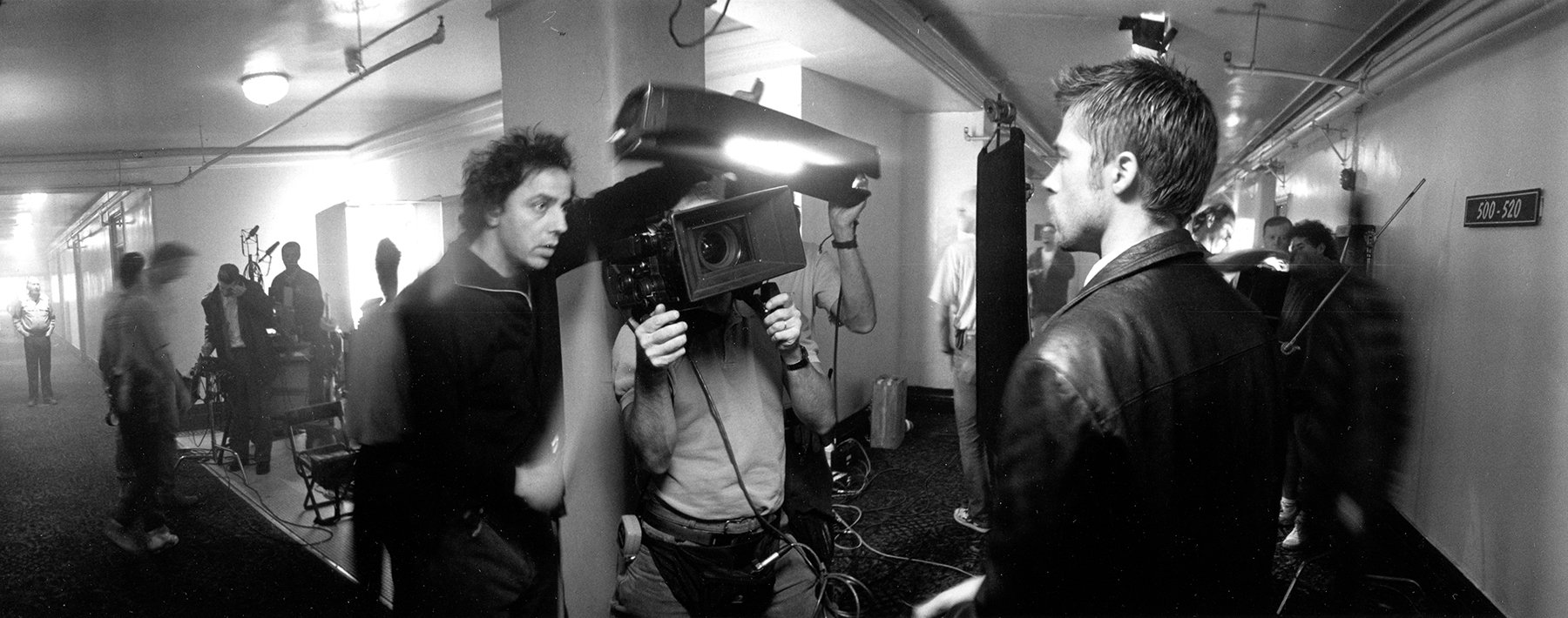

In some cases, like Seven or Boyle’s The Beach (AC Feb. ’00), his deepened understanding of his craft came not only from his work with the directors, but the actors as well. “I’ve always been fascinated by actors — the looks in their eyes, the textures of their voices, their skin tones, how they appear when in costume, their distance from the camera. On Seven, Brad Pitt was young, but he understood immediately where the light was going. And with Morgan Freeman, his voice was so important that it would give me a feeling for the key on the light. I remember watching the toplight coming down on his face and his eyes, and feeling like he was already made as a classic image.

On The Beach, I had the same instinctive feeling with Leonardo DiCaprio that I had with Brad. I was operating on that film — as opposed to Seven, where I wasn’t — so I was constantly fiddling with camera height. But Leo was an engine, moving from shot to shot. He would ‘dictate’ the power of the light in different scenes — not by saying anything, but just through gestures. He would make you want to alter your approach just by the way he was playing a scene.

Through his many conversations with Gray, Khondji discovered how best to use visual references in his work. “James is a very cultured man and we would look closely at not only other films — like The Godfather Part II, which he especially loves — but paintings by Caravaggio, Rembrandt and Poussin. But with references, we were never trying to reproduce where the light was coming from, or what I’m seeing in them. What we were interested in was capturing the feel of a reference: the impression, or the temperature of the room in the painting. James and I have learned a lot about lighting from the great painters, but whenever we created scenes for his movies, what we really wanted to capture were the feelings our references instilled within us.”

While making the Safdie brothers’ Uncut Gems, Khondji admits, “I would be lying if I said to you that we meticulously planned everything in the shoot. Every day, we were discovering something. The film is shot almost entirely with long, Panavision C Series lenses, and, usually, when you shoot with long lenses, it would be counterintuitive to move the camera so much. But in Uncut Gems, our visual language combined a lot of tracking with those long lenses. For me, it was a new era — a new way of shooting.”

Khondji asserts that none of these discoveries could have been made if he was not attuned to the creative rhythms of each project. “If the tempo — how the dolly grip, a crane or an actor moves through a scene — is wrong, you can tell immediately that it will result in a bad shot.”

Bong notes that this philosophy guided the making of Okja and his latest feature with Khondji, the forthcoming sci-fi drama Mickey 17: “On both films, rhythm and tempo are the things we discussed the most, because as a director, you have to find the right frequency with your cinematography. And rhythm isn’t only created through editing or the duration of shots, but also with camera movement, composition, color and the contrast of light.”

“It might seem obvious,” Khondji says, “but it wasn’t for me until my later years: Everything in moviemaking is about rhythm. Some directors I work with will be on their headsets just listening to each scene as we film — they won’t even need to watch! When the rhythm is right, it’s incredible. When the camera and everything in the frame are in rhythm together, it’s like music. And that’s more important than anything.”

You'll find our complete report on the 37th Annual ASC Awards, including the presentation of Khondji's honor and his acceptance speech, here.