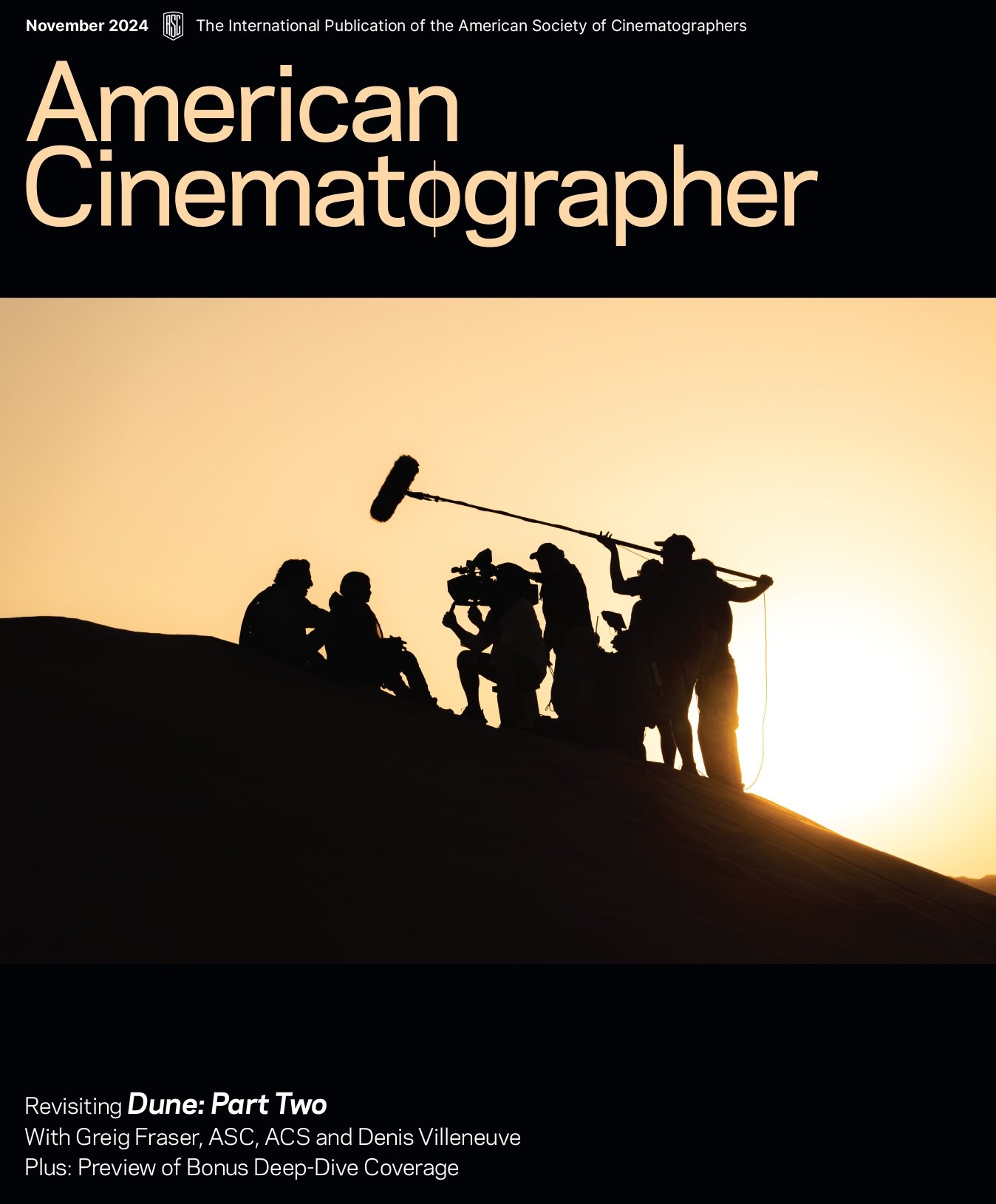

Expanding the View for Dune: Part Two

Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS and director Denis Villeneuve broaden their outlook and toolkit for the second chapter of the sci-fi epic.

Unit photography by Niko Tavernise. All images courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures.

Returning to planet Arrakis presented the Dune: Part Two filmmakers with the opportunity to envision the vast, arid landscape they had created for Part One (AC Dec. ’21) from a more seasoned perspective — and with a wider range of tools at the ready. Nevertheless, Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS called the sequel “the hardest film I’ve ever done, from a practical standpoint” thanks to “all the spinning plates and units going at the same time.”

Director Denis Villeneuve adds that for this second chapter, “the visual vocabulary that we designed for Part Two had to have some continuity with Part One, so you can watch them back-to-back and be in the same world — but Greig and I also wanted to challenge ourselves and make sure we expanded our language and brought a feeling of novelty.

“Especially in the beginning, we wanted to show the technique of the Fremen, [who use] the light of an eclipse to battle their enemies and bring violence with the darkness,” the director adds. “I wanted a bit of a shock at the opening of the film — what [editor] Joe Walker called ‘putting a cold, wet swimsuit back on’ — that kind of shock and energy.

Set shortly after the events depicted in Part One, Part Two establishes that the intergalactic battle for Spice continues, and war has returned to Arrakis. Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet) and his pregnant mother, Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson) — the lone survivors of the Harkonnens’ attack on House Atreides — take refuge on the desert planet. There, Paul begins to understand that his destiny is to lead the indigenous Fremen in their battle against the Harkonnen for control of their planet.

Spherical Only

One notable variation in the visual strategy for the sequel was the decision to shoot only spherical lenses, while Part One was shot with a mix of anamorphic and spherical. “It’s strange — maybe I’ve been ‘Deakinized,’” Villeneuve muses, referring to his multiple collaborations with spherical-format adherent Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC. “But the more I use anamorphic, the more I’m convinced I’m a spherical guy. I adore the spherical look and found that I was trying to play with that language in the anamorphic world, and it wasn’t quite right.”

Another significant change was that while just more than half of the Part One material was composed for Imax, the filmmakers shot Part Two entirely for Imax 1.43:1 (while protecting 1.90:1 for digital Imax exhibition and 2.39:1 for traditional theatrical exhibition and home release). Fraser notes that this decision maintains consistency with the first film’s shifting to Imax aspect ratio when Paul is on Arrakis — as the second film takes place almost entirely on that planet.

Fraser decided to turn again to the Arri Rental Alexa 65 as his main camera, supplementing it with Arri Alexa LF and Mini LF cameras when more — or more compact — bodies were required. During his typically ambitious testing of optics, he happened on the Arri Rental Moviecam lenses, a series of rehoused Olympus OM still-photography lenses that was introduced by Moviecam in the 1980s and was subsequently acquired by Arri Rental. Fraser determined that the Moviecams delivered the feel he was looking for — and decided to team them, when needed, with his own set of Optica Elite primes.

“Greig and I also wanted to challenge ourselves and make sure we expanded our language and brought a feeling of novelty.”

— Denis Villeneuve

As shooting commenced, he also began incorporating the IronGlass Adapter rehoused Soviet-era lenses that he had used on The Batman (AC June ’22) and liked the look he was getting, but the mechanics weren’t yet up to the demands of being a primary set for a major production. He contacted Alan Besedin of Vintage Lenses for Video, an IronGlass partner. “I said, ‘I want more of these, but they need to have better mechanics,’” Fraser says. “It turned out IronGlass was just releasing their MKII mechanical design, and it was substantially better than the previous one, so I ordered three 85mm [Jupiter-9], three 58mm [Helios 44-2] and three 37mm [Mir-1V], which were rushed to me.”

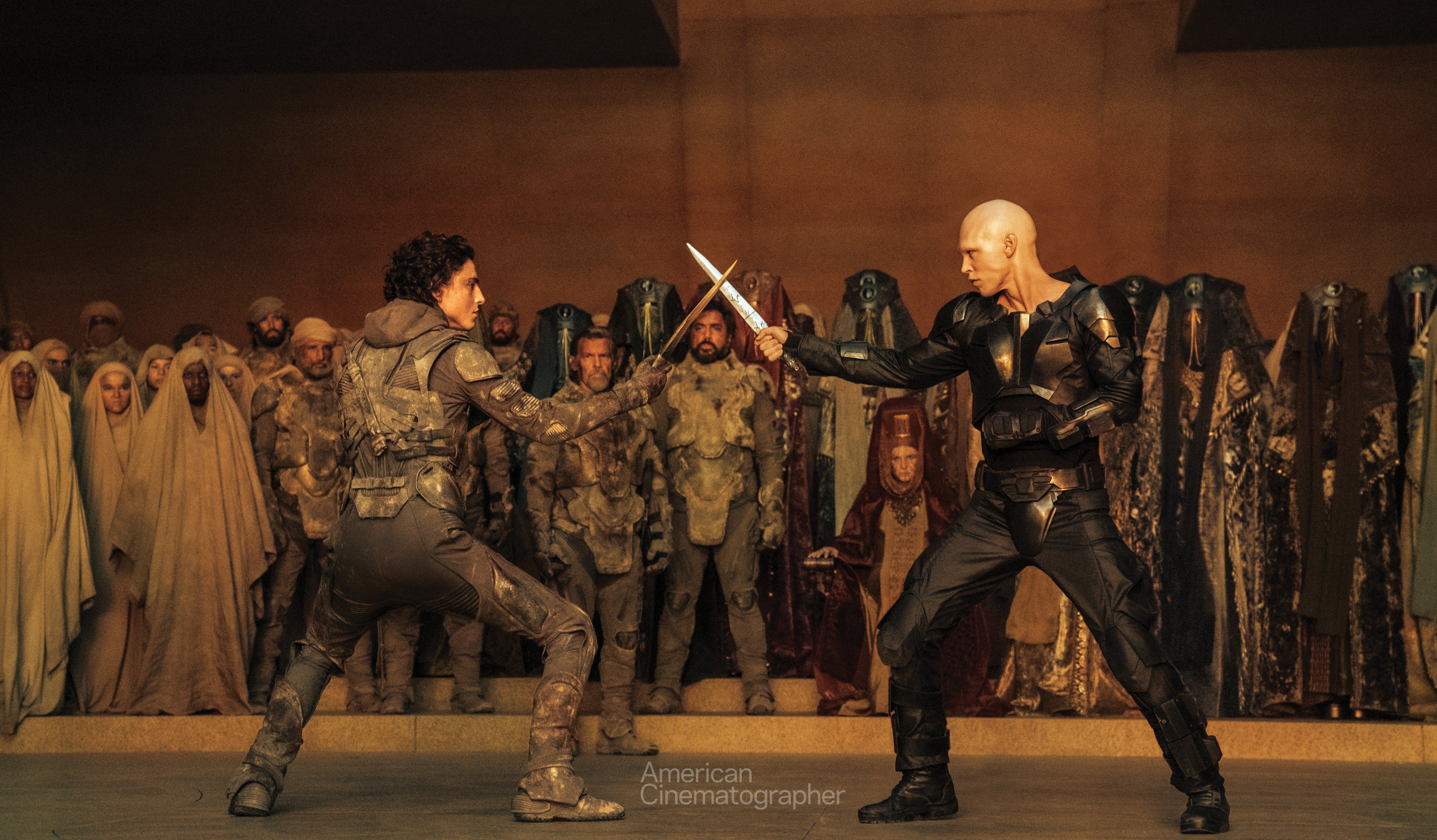

As principal photography progressed, he continues, “We became bolder and more focused on choosing lenses [based on which aspect of the story] we wanted to tell. The Moviecams worked really well for the sandworm ride, for instance; they’re generally a bit sharper than some other lenses we carried and were great for all that texture — with the wind and sand and haze. We also used the Moviecams for the arena fight and the infrared sequences, because their ability to resolve was important.

“For the desert and more of Paul’s story, we used more of the IronGlass and Optica Elite lenses, which are softer and have more character.

“There is a democratization of lens-building right now. Several companies are doing fantastic work in rehousing stills glass. In today’s world, we’re also able to work with mounts that are not just PL or PV, but LPL, L, E and M. That’s opening up quite an exciting world that goes far beyond what we’ve been used to in the past. I feel these companies that are rehousing, including Zero Optik in L.A., need to be encouraged and supported to do more of it.”

Getting Closer

Another visual goal on Part Two was to move in just a little closer to Chalamet. Whereas the actor was typically filmed with a 55mm or 75mm lens on Part One, Fraser relied on 58mm, 85mm and 135mm this time around. “We felt that would make it more intense, so I went just slightly longer on the focal-length choices,” the cinematographer says.

Notes Villeneuve, “I learn from every movie I do, [and] when I finished Part One, I felt that we didn’t get close enough to Paul. I wanted to be closer in on his eyes and feel the pressure that was on him. Getting closer on this film was achieving more precision in our visual language.”

Fraser also maintained a fairly shallow depth of field, especially for Chalamet’s scenes. “It was a balancing act, [because] I didn’t want to have any focus buzzing, so I tried to give my focus puller, Jake Marcuson, a bit more T-stop to allow a bit more flexibility and find that balance. Often, though, I find stopping down too much can adversely affect the contrast, and increase the resolution unfavorably, so balance was the key.”

The cinematographer was usually ND’ing down to stay fairly wide open; Formatt Hitech Firecrest IRNDs were his preference, as they were on Part One. (Firecrest is the trade name for Formatt’s proprietary coating technology.) “They’re really resilient, and we were putting them through extreme desert conditions,” Fraser notes. “The color fidelity is excellent, which is very important to me.”

Another filter he tapped was a variable IR filter, which allowed him to vary the amount of blue and green hitting the sensor, to create the effect of the eclipse on Arrakis. “The sunlight is unstable, and the Fremen use that transition [of light] in order to attack at the darkest part of the eclipse,” Villeneuve says.

Adds Fraser, “We tested creating that effect in the grade, but it just didn’t work as well. I needed to use the filter to achieve a strong red tone with hints of green and blue that is very different from the first film [and] justified by the eclipse.”

“Nightmarish Black-and-White”

Frank Herbert’s novel Dune offers few details about the look of the Harkonnen home planet, Giedi Prime. The filmmakers were excited to explore the possibilities. Villeneuve explains, “We know Giedi Prime is an industrial planet with all links cut to the natural world; it is a plastic-like planet, no longer one with any nature. We are shaped by our environments, and Greig and I talked about what would [suggest] the psyche of the Harkonnens, how they see reality. We came up with the idea that [their] sunlight has no color, and we both got very excited about that — some kind of nightmarish black-and-white. Greig [suggested] shooting in IR, and I loved it.”

This concept is highlighted in an arena battle dominated by sociopathic and power-hungry Feyd-Rautha (Austin Butler) — the youngest nephew of Harkonnen leader Baron Vladimir Harkonnen (Stellan Skarsgård) — who doesn’t hesitate to murder at the slightest whim. “We did an initial test that Denis loved,” recalls Fraser. The idea — which incorporated a bit of science-fiction license regarding how people in the world of Dune see light — “was that these very pale, white-skinned characters looked like that because there was no visible light from the sun on Giedi Prime, only infrared. So, when characters move from indoor artificial light to outdoor natural light, they go from visible light into infrared light and pure black-and-white.”

Fraser shot this material using the Alexa LF and Mini LF with the IR cut filter removed from the sensor, which created a color IR image. He then incorporated an 87C filter, which cuts all visible spectrum and allows only IR to pass through. The resulting image was further desaturated in post.

“It’s a very strange effect,” Villeneuve enthuses. “I had experimented a little bit with IR in the past, but never for a full sequence, and [the image] feels really alien. The thing about shooting this way is that you cannot go back! There’s no bringing back a normal image once you cut the visible light, but I love that! I love to commit as we shoot.”

Inevitably, the lack of visible light altered the appearance of many of the costumes designed by Jacqueline West. “With fabrics in front of the camera, the results could be very unpredictable, and she had to [change the material of] many of the costumes specifically to work in IR, to keep them solid black,” Fraser says.

“Sci-Fi Sh*t”

Fraser enjoys the creative flexibility inherent in science-fiction films. “It allows you to back up your concepts [about] ‘stuff that looks cool’ and make them make sense!” he says with a laugh. “Denis is a master of that — he’ll say, ‘Okay, this is where we do some sci-fi sh*t.’ In sci-fi, we’re not playing by the conventional rules of lighting and hardware; we can stretch things a bit and imagine a lot more.”

As an example, he points to a sequence in which Gurney Halleck (Josh Brolin), the former military leader of House Atreides, leads Paul and Chani to a hidden Atreides vault filled with nuclear weapons.

“We thought, ‘How should we light this ancient vault? Flashlights? Built-in lights?’ That all seemed boring and conventional, and for us that would be a letdown,” Fraser says. “What is the sci-fi version of turning on the lights that isn’t gratuitous in a location where there’s no natural light? We had established these ‘suspensor’ lights in Part One — floating balls of light that move of their own volition — and decided to create a portable variation of that.”

Paul opens the vault with a lock that recognizes his royal Atreides heritage — and as Gurney leads them inside, he tosses a ball into the vault, where it floats in midair, projecting concentric ribbons of light that illuminate their way.

Fraser recalls, “First, [production designer] Patrice [Vermette] created some conceptual art based on Denis’ and my ideas. I took his drawings to Jamie Mills, my gaffer, and Guy Micheletti, my key grip, and said, ‘How do we do this?’ After some trial and error [experimenting with] sources that would create a super-sharp, 360-degree strip of light, Jamie found old tungsten fog lamps for automobiles that worked beautifully. They’re very focused.”

Mills and Micheletti rigged a piece of square steel with four rows of lamps, one on each side of the steel, with five fog lamps on each side. This created five very sharp strips of light that wrapped 360 degrees around the tubular vault walls. This light rig was then attached to a stripped-down Libra head on the end of a telescoping crane arm that was later painted out in post. The combination allowed the light rig to “float” down the vault hallway on the crane arm and then rotate on the Libra head as the light enters the vault, revealing the atomic arsenal.

Signature Moments

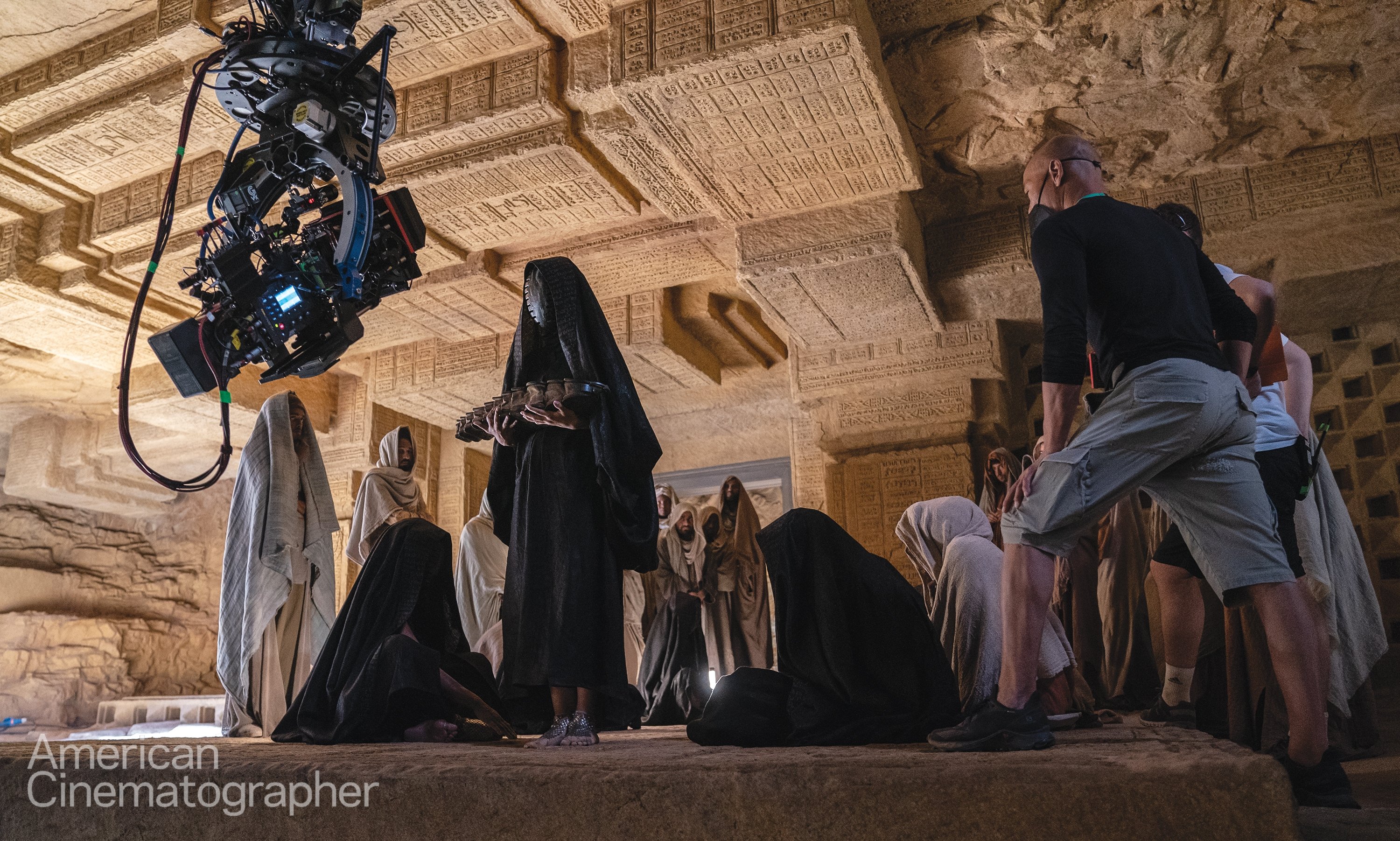

One of the Fremen’s best defenses is that they live underground, which keeps them safe from the oppressive sun and attacking forces. In one sequence, Fremen leader Stilgard (Javier Bardem) brings Paul to the underground Sietch to meet the Fremen elders.

“The Sietch lighting was a bit of a head-scratcher,” Fraser notes. “In the book, the Sietch is lit by suspensor lights, but Denis and I agreed that those could feel too pretty and not dangerous enough. The Sietch needed to feel hidden and dangerous, particularly when we first get in there. So, we came up with the idea that we’re effectively lighting through slits in the rock that allow sunlight in.”

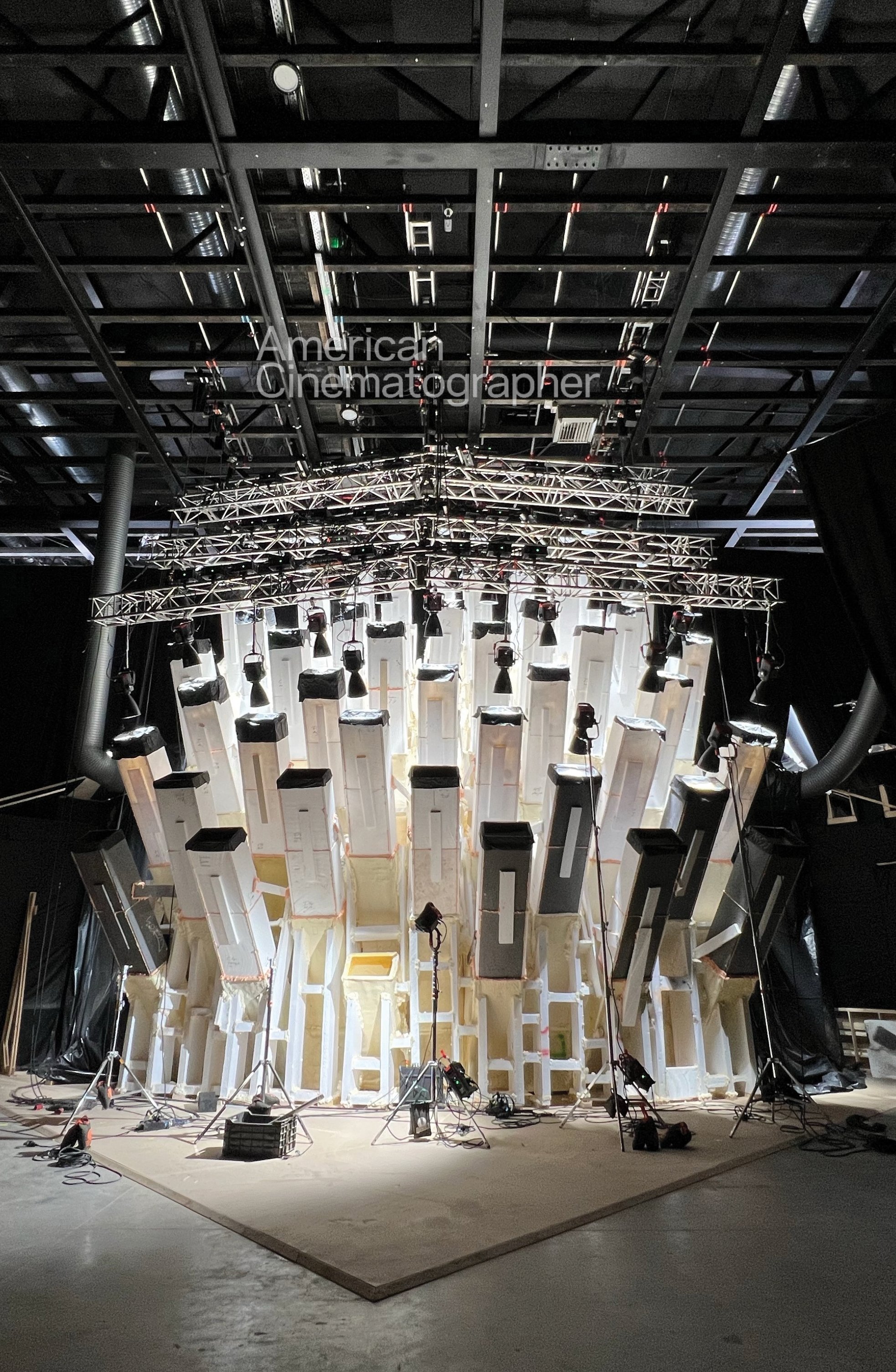

An example of this can be seen in the Sietch Tabr Communal Dome Room, a set built on Origo Stage 5 in Budapest, Hungary. Paul and his mother eat a meal under the suspicious, judgmental eyes of many Fremen around them. The wall behind Paul is a checkerboard of square openings of light. Each opening represents a long, diagonal shaft that leads to the surface to allow light in.

“[Vermette’s] artwork was such that the light coming through those shafts was quite sharp and edgy, and we just couldn’t, for the life of us, get a sharp-enough light from our existing arsenal,” Fraser says. “I was really staying with LED and away from tungsten, but the LEDs and even Dinos weren’t getting us the light we needed. I called up Aputure and said, ‘Whattaya got?’ — and they sent us more than 50 1200d Pro fixtures that did the job beautifully.”

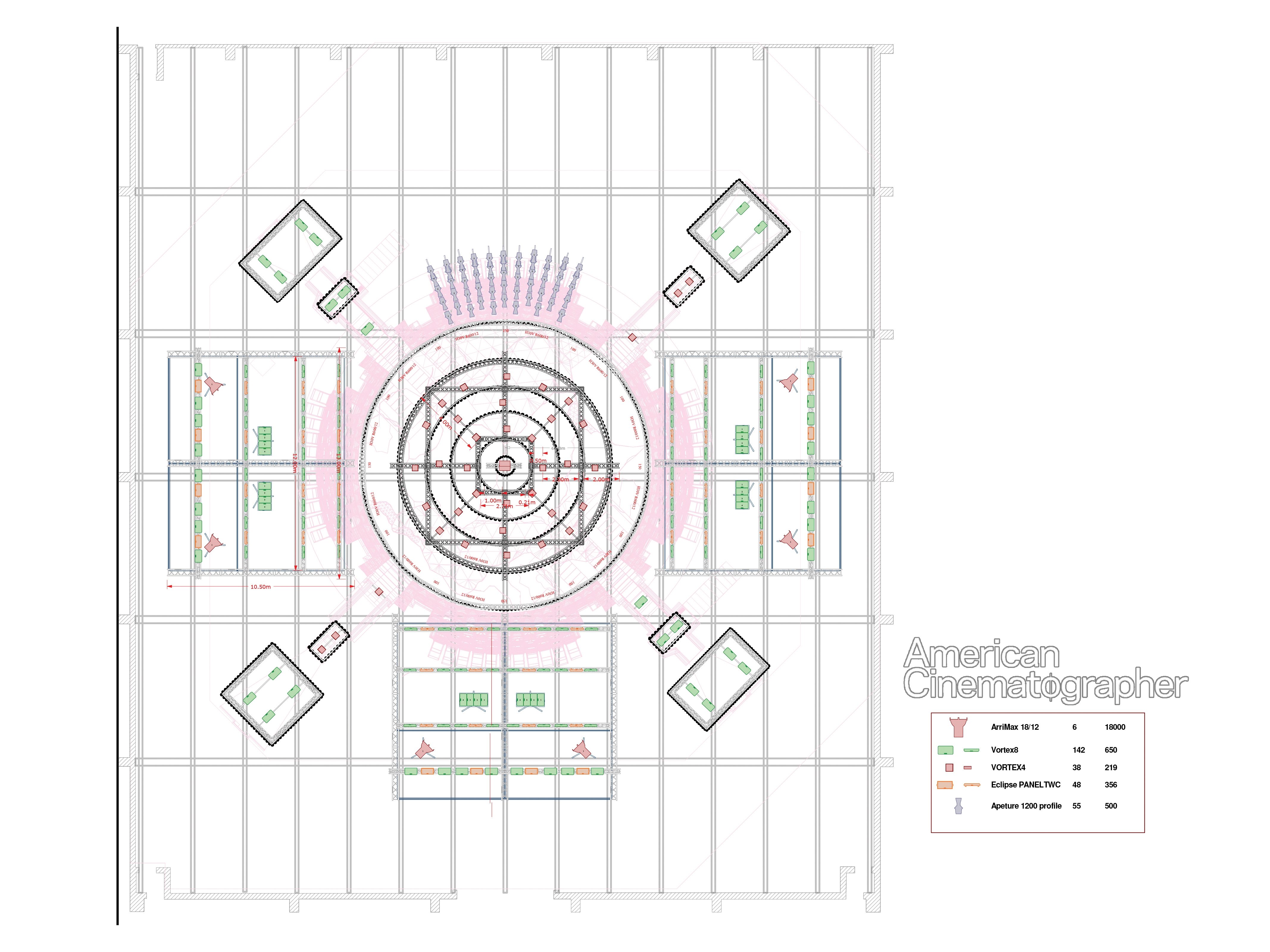

Gaffer Mills created long, square shafts of white bead-board for each of the checkerboard squares with one Aputure 1200d Pro fixture per square. The result was 55 fixtures and tubes rigged up on box truss and integrated with the set walls.

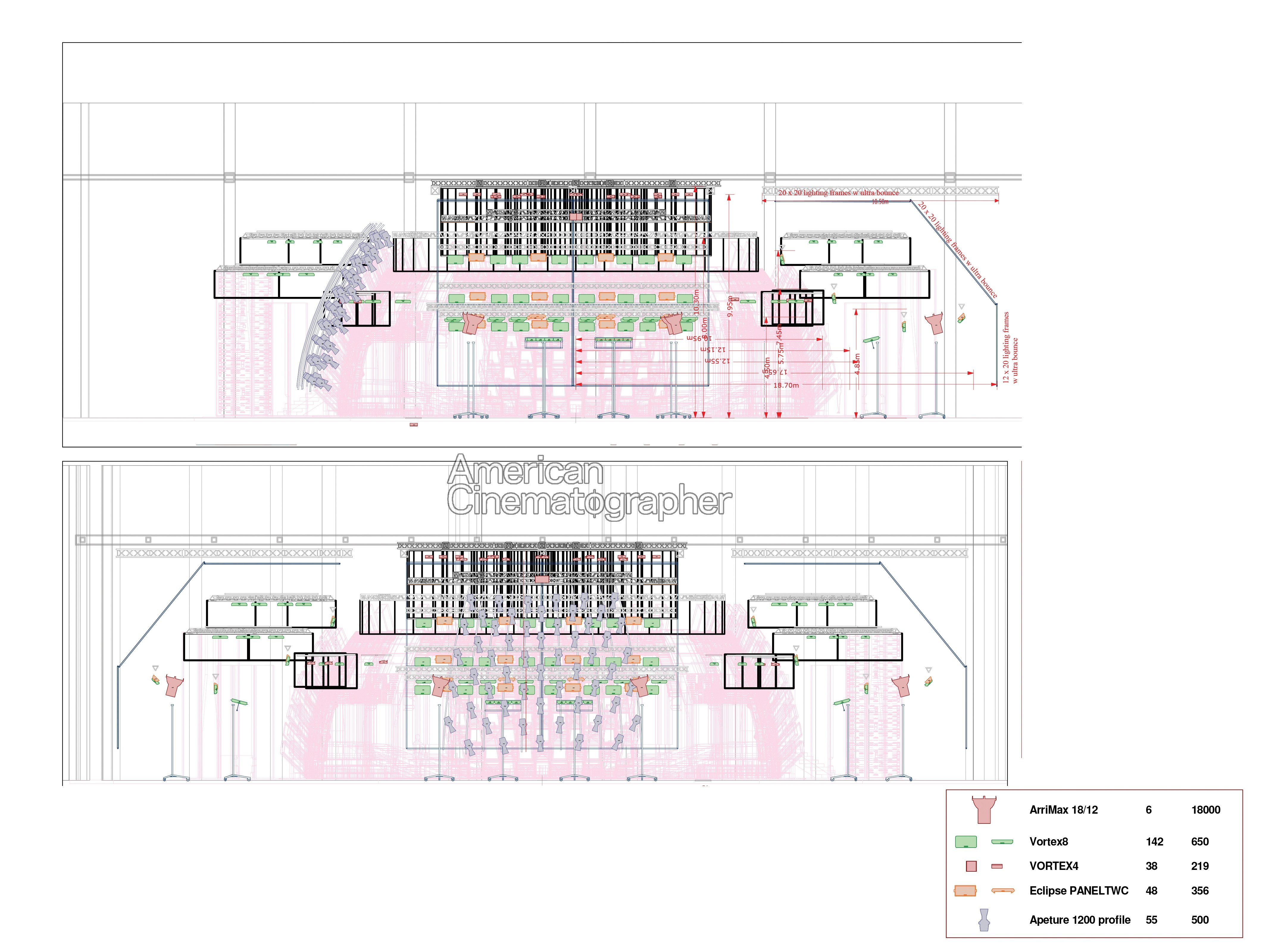

On the three dimmer sides of the dome, which were not receiving direct sunlight, Mills created vertically curved coves (like a candy cane) of 10 12'x20' Ultra Bounce frames surrounding each of these three sides of the set. He then bounced two ArriMax 18Ks and 50 Creamsource Vortex8 panels into each cove to create the necessary soft ambience.

For the main area inside the dome, the team rigged a 52' circular soft box overhead, covering it with Magic Cloth. Inside the box were 32 Vortex4s. Concentric rings of black teasers, each about 8' in height, were spaced about every 6' along the diameter, getting progressively smaller in circumference toward the center. The result is a bulls-eye-shaped overhead soft source.

Fraser used these concentric rings to control the light in specific areas by turning fixtures on or off, depending on the location and focal length of the shot.

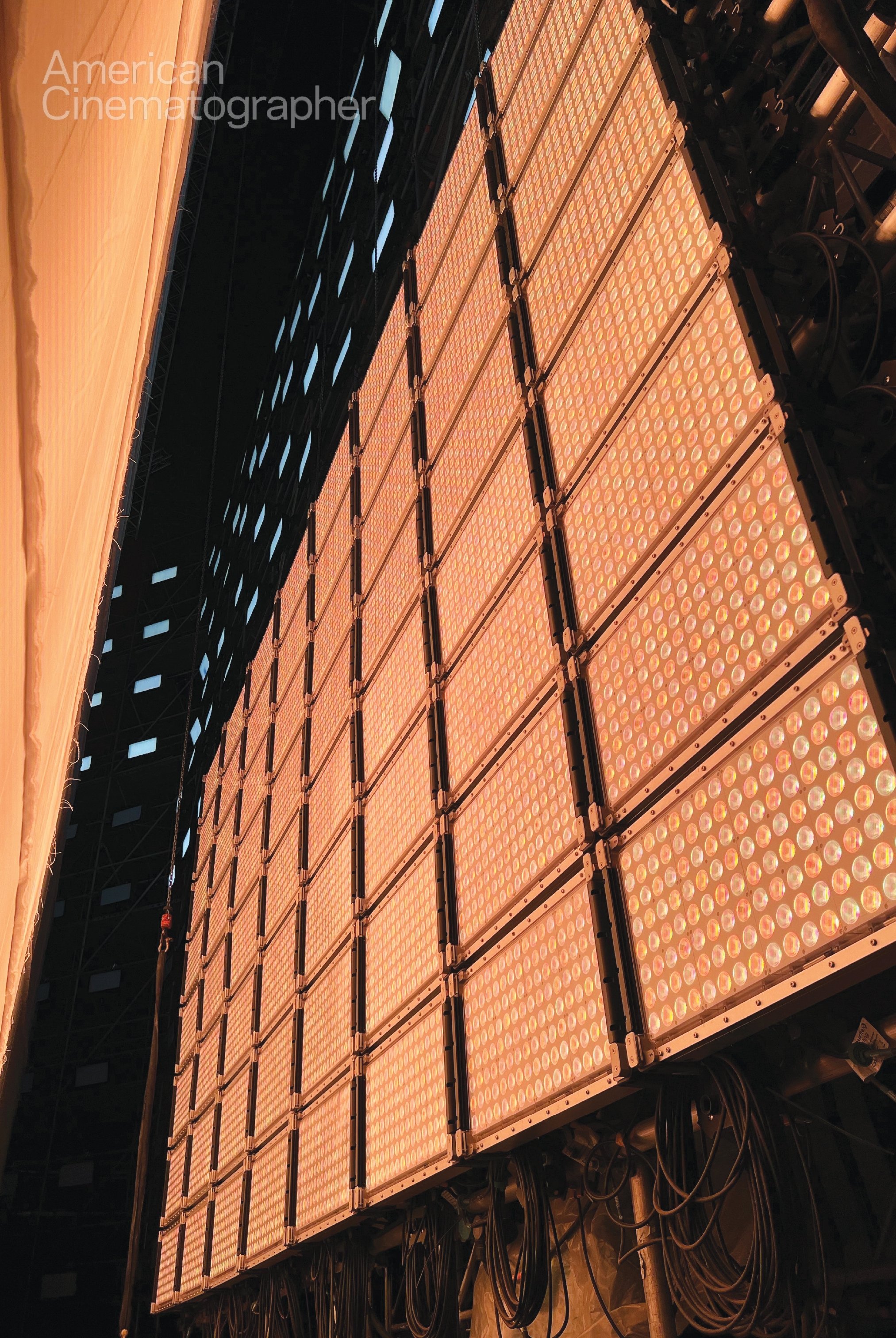

The climactic duel between Paul and Feyd-Rautha takes place in the Arrakeen Residency War Room, which was constructed on Stage 6 at Origo. One wall of the room is a huge, open window to the Arrakis sky, and the sun is rising as the battle ensues. This sunrise mirrors one earlier in the film, when Chani and Paul connect romantically.

“I felt deep in my bones that the end of the film needed to have that sunrise quality, that the audience needed to connect with Chani in the same light that she connected to Paul.”

— Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS

“I felt deep in my bones that the end of the film needed to have that sunrise quality, that the audience needed to connect with Chani in the same light that she connected to Paul,” Fraser says. “That romantic scene at sunrise really helps evoke the beautiful feelings between them — and this final battle needed to be a mirror of that. As Paul turns his back on Chani to follow his destiny, it would come full circle that the fiery look of heartbreak in her eyes was in the same light and feeling as when she fell for him.”

To create this second significant sunrise, Mills and his team built a massive truss structure behind a stretch of bleached muslin 60' tall by 170' wide. Behind the muslin was a grid of 152 EclPanel TWC Prolight Eclipse fixtures and a rig of 64 Vortex8s attached to form a single source (dubbed the “Vortex512”); these were then pixel-mapped to create a playback of a slowly rising ball of sun in the War Room window.

Throughout the production of the film, Fraser says, “We would often have multiple units running simultaneously, but all being piped back into the tent for Denis and me to oversee. The intricacy of Paul’s [sandworm] riding work, all the way to the sequences with [Paul’s unborn sister] Alia in utero, meant we needed lots of time to get these shots exactly right.”

A Powerful Relationship

Reflecting on his epic collaboration with Fraser, Villeneuve says, “When I decided to make Dune, the only cinematographer I thought of was Greig. It’s about choosing the right person for the right project, and his use of natural light is so very beautiful. I wanted the movie to [avoid] more traditional sci-fi tropes and get as close to nature as possible. I also wanted someone very agile with the camera, who was willing to be close to the body of the camera, and I’m very in love with the work Greig has done.

“The cinematographer-director relationship is a very powerful and intimate one,” he adds. “The cinematographer becomes your brother-in-arms, the one in the trenches with you. You evolve with them; they become very close friends. Greig is a friend and a ‘psychiatrist’ and a close ally. He is also a master at multi-tasking — he can be conversing with another unit’s DP, with production, taking pictures on set, and discussing with me all at the same time, and suddenly, we go for a take, and he calms in the zone and is so focused! I learned so much from him. I’m so glad we did these movies together.”

Tech Specs

1.43:1, 1.90:1, 2.39:1

Cameras | Arri Rental Alexa 65; Arri Alexa LF, Alexa Mini LF

Lenses | Arri Rental Moviecam (Olympus OM), Prime DNA; IronGlass (Helios, Jupiter, Mir); Optica Elite; Zero Optik Rokkor

The cinematographer and director later sat down for this episode of ASC Clubhouse Conversations in discussion with Wally Pfister, ASC:

UNREAL FOR THE CAMERA TEAM

Epic Games’ Unreal Engine has become a key component of virtual production, previs and visual effects, but Fraser took the novel step of integrating the software into his department for planning on Part Two — and hiring a cinematography assistant, Tamás Papp, who was skilled in the technology.

Papp — whose work “ended up being far more advanced than that of a cinematographer’s assistant,” Fraser says, and who is credited as virtual-cinematography technician on the film — used drone scout footage and photographs of the locations to create precise 3D environments in Unreal Engine. These renderings, combined with the game engine’s built-in sun-tracking feature, enabled Fraser to predict not only exact sun positions months in advance of shooting, but also exact shadow positions.

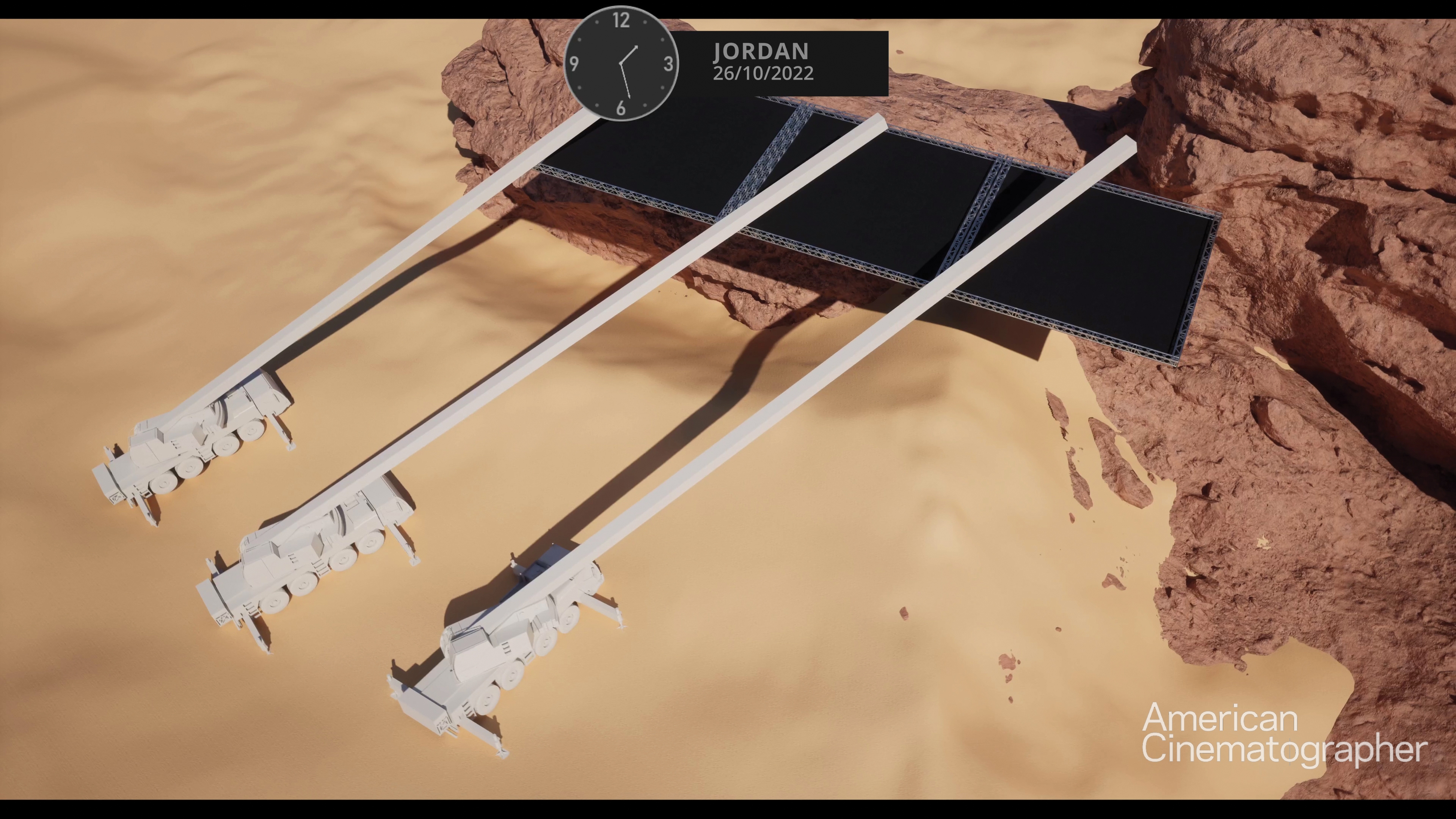

One notable use of Unreal is the sequence depicting the harvester attack: Paul, Chani (Zendaya) and the Fremen try to take out a group of Harkonnen forces by attacking a massive spice-harvesting machine. The fight takes the actors from the blazing Arrakis sun into the shadows cast by the machine’s massive legs and out again. The harvester was a CG element — but on location, Fraser needed to create its large-scale shadows, which the actors would run in and out of.

“We scouted the desert in March, but we weren’t shooting until October,” he explains. “The shadows are critical in the sequence, and we had to schedule precisely. With Unreal, we could determine that we needed to shoot a particular shot between 9:03 and 9:43 a.m., for example, to get the shadows right. Regular sun-tracking apps and a compass can give you a lot of information, but they’re really blunt tools for fine precision. Unreal was an invaluable tool that allowed us to be as efficient as possible.”

Papp also built grip hardware in Unreal that helped Fraser determine well in advance exactly what gear he would need to create the shadows and then share that information with the producers. “It’s one thing to ask for a condor or two for a sequence, but when you’re asking for four construction cranes and more than 20 telehandlers, it becomes an eyebrow-raising discussion!” Fraser says. But with the Unreal simulation, the cinematographer could demonstrate that with 40'x40' solids on each of four 150-ton construction cranes, and 20'x20' solids on 24 individual telehandlers, he could create the exact shadows required to represent the enormous machine above them. “There wasn’t a question of what we needed — one less crane, and we wouldn’t have been able to do what was planned,” he says. “It was really critical to justify the massive expense and logistics required to get cranes out there.”

Further, the Unreal planning showed the exact configuration of each crane and telehandler for every portion of the sequence, so the crew was well prepared to quickly reposition them as required. As a result, the filmmakers were able to shoot the entire sequence in the natural light of the Jordanian and Abu Dhabi deserts.

“Typically, this kind of tool is within the purview of the visual-effects, previs or techvis departments, and we’re reliant on them to create the Unreal assets and to visualize the sequence — often without significant input from the cinematographer,” Fraser continues. “That takes the control out of our hands. By having a person using Unreal in my department, standing on set with me and the director and the AD, we were able to communicate more precisely, to plan more carefully, and to optimize time and resources. If the director asked, ‘Are 100 extras enough for this scene?’ Tamás could quickly replicate 100 digital humans in the digital set he’d created and give us the answer in a minute or two. That’s a really powerful tool! “

Producers need to understand how effective Unreal is and the value of hiring a cinematography assistant who knows the technology,” Fraser continues. “The more other departments are in sole control of this tech, the more its use becomes skewed toward their needs, and less toward ours. The beauty of Unreal is that we could — and should — have Unreal experts in almost every department, each representing their own department’s expertise. Unreal can be used effectively by most departments from art through construction, including stunts and camera/lighting. One sole platform can share assets and help each department become more efficient.

“I personally recommend every young person starting out in the film biz learn Unreal — whether they’re interested in VFX or not.”

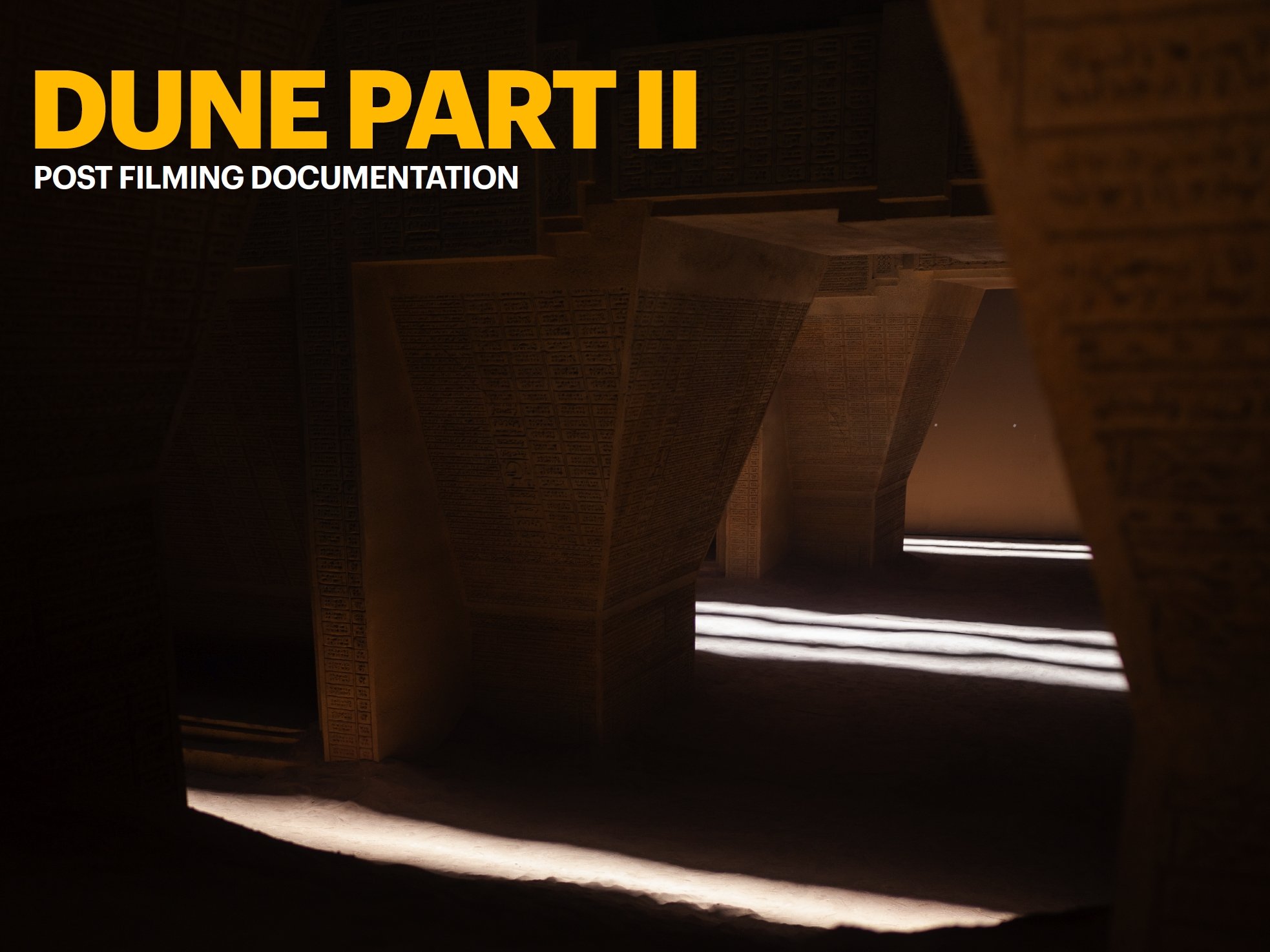

A DEEPER LOOK AT DUNE: PART TWO

This represents an excerpt from “Afterfilming,” a record created by virtual-cinematography technician Tamás Papp for Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS during production. A much-extended version of the document is available at Dune: Part Two — “Afterfilming” Reveals Creative Approach. These materials appear here with the permission of the filmmakers and Warner Bros. The cinematographer offers this overview:

This document started as a collection of lighting plans, but also a formal record of all the sets from Dune: Part Two. You never really know when you’re going to have to go back and reshoot a set or do pickups, even with a really disciplined director like Denis Villeneuve. There’s also the possibility you’ll need to shoot another movie on the same set — or on an identical rebuild — for a sequel or spinoff. So, recording and photographing these sets from a technical standpoint was important.

One of the things I really love about this document is that it spotlights Patrice Vermette’s sets. Patrice made some of the most delicate and beautiful pieces of art that I’ve ever laid eyes on — let alone committed to film — and when I asked Tamás to photograph each setup, I also asked him to give love to the sets themselves in his photos. Sets often play second fiddle to the actors and cinematography, but this document gives me a chance to experience them, explore them and enjoy them in a different way. I’m very happy that now others can admire them, too.

I do this kind of record-keeping as often as I can, and I know many other cinematographers do, but it is seldom shared beyond the production, and that’s a shame. It does take another person to create such a document, but it is not just helpful for all the obvious practical reasons; it can also be enlightening and even inspiring. I’m excited to share this with American Cinematographer and give you all a deeper look at how we made these beautiful sets come to life. — Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS

Not an AC subscriber yet? Become one today.