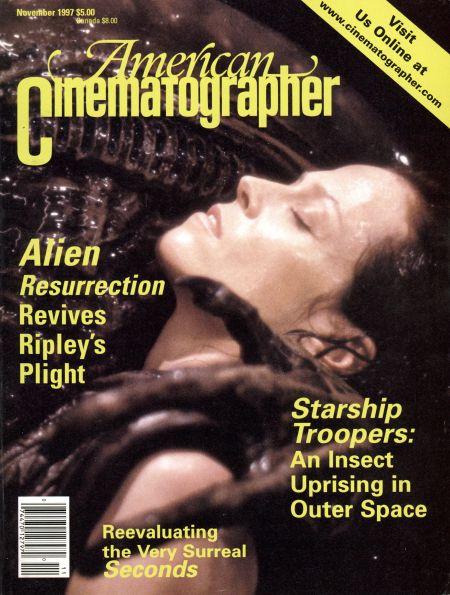

Malevolent Mutations: Alien Resurrection

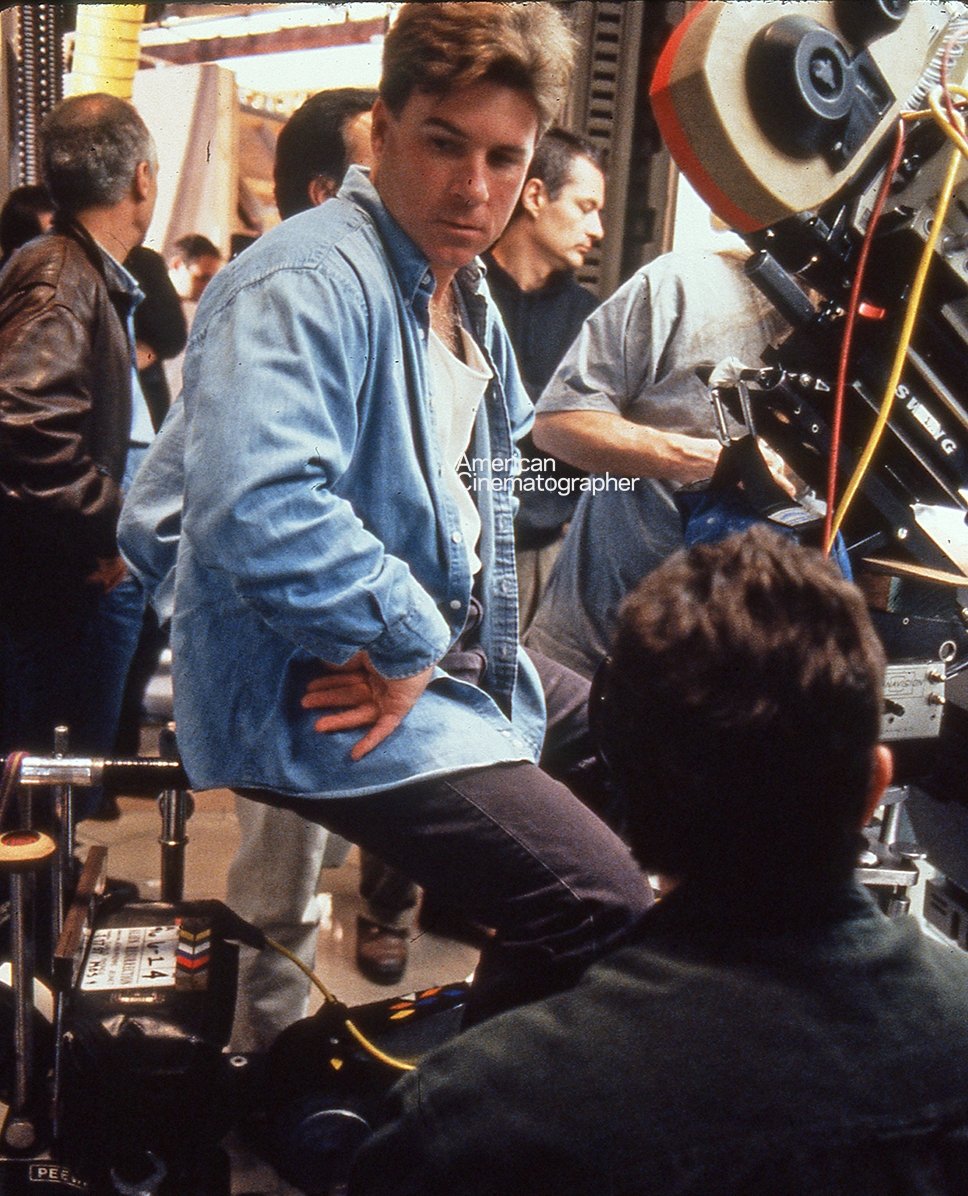

Director Jean-Pierre Jeunet and cinematographer Darius Khondji, AFC revisit infamous extraterrestrial enemies.

Unit photography by Suzanne Tenner and Sam Urdank, Courtesy of 20th Century Fox

In the summer of 1979, an ominous decree (“In space, no one can hear you scream…”) was issued to legions of unsuspecting moviegoers. Skillfully directed by Ridley Scott and photographed by Derek Vanlint, CSC, Alien became an instant genre classic whose novel look influenced a score of imitators. The film's menacing, claustrophobic atmosphere, nightmarish bio-mechanical alien creatures (designed by Swiss surrealist H.R. Giger), and haunting visuals tapped directly into the terror regions of the human psyche.

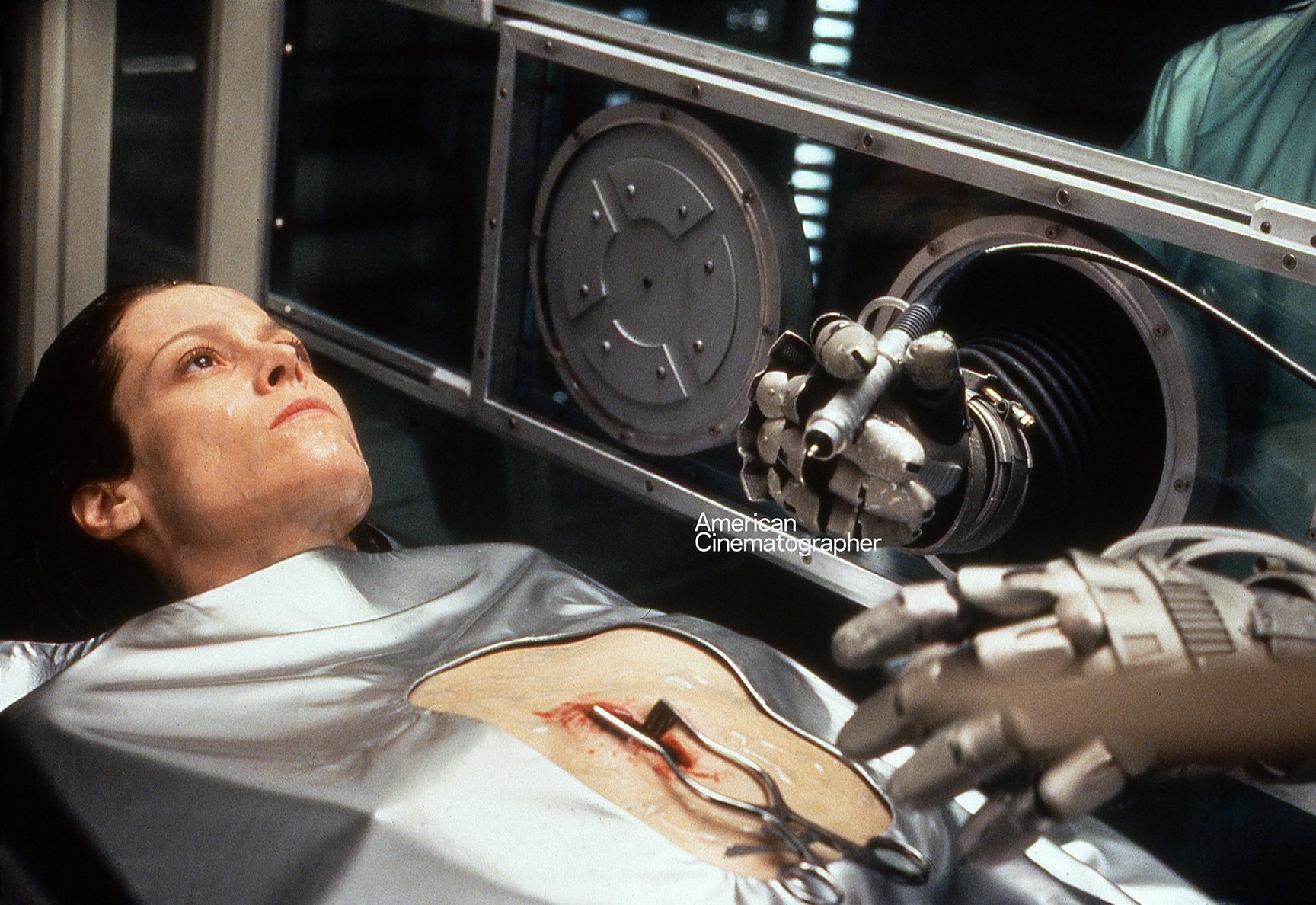

Writer/director James Cameron and Adrian Biddle, BSC then conspired on Aliens, a high-energy 1986 sequel which redefined the original film's shock appeal with swarms of the insect-like xenomorphs. Six years later, director David Fincher and cinematographer Alex Thomson, BSC crafted the stylishly nihilistic Alien3, in which the series' much-beleaguered heroine, Lt. Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver), was finally bested by her devilish tormentors: implanted with an alien embryo, she made a suicidal leap into a vat of molten lead in the film's self-sacrificial climax.

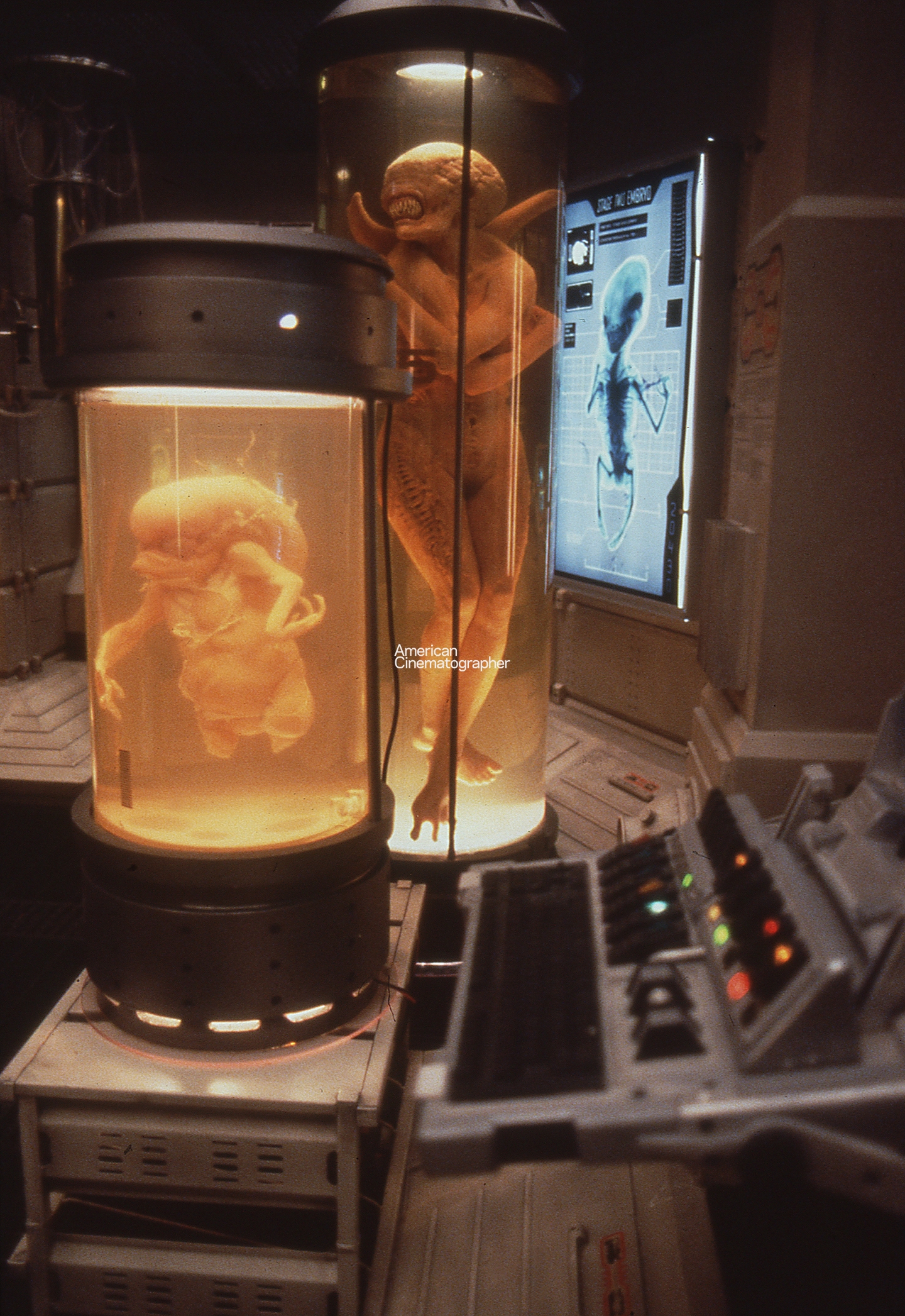

In killing off this popular protagonist, 20th Century Fox left itself with something of a predicament for further sequels. However, Alien Resurrection screenwriter Joss Whedon provided a viable narrative solution: reincarnate Ripley and her demons by cloning surviving samples of her alien-tainted DNA. This unholy genetic inter-mixture produces a reborn Ripley and an exotic array of fiendish extraterrestrials — bonded by their shared bloodline. From there, all hell breaks loose.

“This film represents the first time I’ve directed a film that I haven’t written, and it is a sequel, so I wanted to respect the spirit of the previous pictures. That was very important to me.”

— director Jean-Pierre Jeunet

Helming Alien Resurrection is French director Jean-Pierre Jeunet, who created the dark, acclaimed fantasies Delicatessen and The City of Lost Children with filmmaking partner Marc Caro. “There are several aspects of this picture that are similar to my other movies," remarks Jeunet. “In fact, in filming some shots for Alien Resurrection, I realized that I had composed similar ones in both Delicatessen and The City of Lost Children. However, this film represents the first time I've directed a film that I haven't written, and it is a sequel, so I wanted to respect the spirit of the previous pictures. That was very important to me."

Jeunet took an interest in cinema at an early age. After leaving school at 17 and going to work at a telephone company, he bought a Super 8 camera and began making short animated films. After four years of creative experimentation tempered by professional monotony, he relocated to Paris and later met cartoonist Marc Caro. The duo began their collaboration with the animated short The Escape; their second short, The Merry-Go-Round, earned a 1981 Cesar Award, the Gallic equivalent of an Academy Award. They quickly followed up with the 28-minute, black-and-white short The Bunker of the Last Gunshots, which took a year to make as Jeunet served as co-writer and co-director (with Caro), cinematographer, producer, editor, sound cutter and negative cutter. Bunker would go on to play for five years at a Parisian theater on a Saturday midnight double-bill with David Lynch's Eraserhead. These shorts launched Jeunet's entry into the realm of commercials and music videos — culminating in his feature debut, Delicatessen.

On Alien Resurrection, his first U.S. studio feature, Jeunet could think of no other cinematographer with whom he'd rather work than Darius Khondji, AFC, who photographed both of the director's previous films. "At the beginning," reveals the director, "I thought this film would be too difficult for me. It was my goal just to survive Hollywood and make the film, because for a French director, making a film in Hollywood is a dream and a nightmare at the same time! So it was very reassuring for me to work with Darius. After I started work on Alien, though, I discovered that [making a major American studio picture] involved pretty much the same procedures that I had used in France."

“I would like to think that my methods change according to the director that I’m working with and the story that I’m telling visually.”

— Darius Khondji, AFC

"I was lucky on this picture to be hired very early on in preproduction," Khondji says. "I started preparation 12 weeks before principal photography, which is very unique. Some of the design drawings were already done, but I saw most of the drawings coming out in the preproduction. Jean-Pierre and I worked very closely with production designer Nigel Phelps (Judge Dredd), and I think he's really the genius of this movie — his designs gave the film an incredible and very special look.”

Khondji and Phelps soon began a series of photographic tests to devise the film's look and color palette. As in all of his prior work, the cinematographer knew that he would be incorporating some form of contrast-enhancement process in the lab to craft the emulsion's latitude to his liking, based on his response to the film's story and characters. The tests would determine which type of process would be used, and to what extent. "I don't think I've ever done so many tests for a film before," relates Khondji. "I experiment a lot during the testing, so I try to get the lab's participation very early on in the production. I also like to have the lab people read the script. I always view my work as a group effort, and I feel it's important to think of my position as perhaps the director of an orchestra. Within that philosophy, I think of the lab as almost an art director of the processing chemistry, and my color timer, Yvan Lucas, as another art director working with the printing.

"In my tests, I try to damage the negative as much as I possibly can — underexposing and overexposing it. The people in the lab call me the 'Dracula' of the negative because I like to destroy it. From the ashes comes something new, and I sometimes find very strange imagery that I never would have been aware of if I hadn't gone through the tests. For example, by overexposing by three stops, you may be actually exposing something at key that would normally be very underexposed."

Through his tests, Khondji determined that he would be incorporating Technicolor's ENR process — which he had recently utilized to great effect on Evita (see AC Jan. '97) — and Eastman Kodak EXR 5293 and Vision 500T 5279 stocks. He gradually used more and more of the 79 as shooting continued until he was exclusively using the high-speed emulsion. Knowing the ENR process would dramatically deepen his blacks, Khondji utilized a Panaflasher during certain low-light sequences to add detail in the shadows, often simultaneously adding color with warm gels inserted in the device's filter holder.

The cameraman employed Panavision Platinum cameras (as well as an Aaton 35-111 with a Panavision mount for handheld work) with Primo standard and close-focusing primes. He and Jeunet opted to shoot the film in the 2.35:1 Super 35 format, as he had done previously on Seven (AC Oct. '95). "I chose Super 35 not due to lighting issues [spherical lenses are faster], but because I wanted to be able to get dynamic movement and certain camera angles," Khondji submits. "Jean-Pierre wanted the freedom to come in very close to an actor's face with the camera, as he had on his previous two films. With anamorphic lenses, you can't get that close in the same shot, because they tend to deform the actor's face. This was not an issue with spherical lenses. Jean-Pierre likes to place the actors in the frame in a way that creates tension, and often makes them enter at certain cross-angles so that they appear suddenly. He's a very big fan of Sergio Leone and of the way he framed his 'scope films; Leone's work has been a primary inspiration for all of Jean-Pierre's films."

"For me," reveals Jeunet, "Once Upon A Time in the West was a revelation. I was 15 when I first saw it, and I could not even talk for three days afterward. My parents kept asking, 'What's the matter, are you sick?' But I could only raise my hand as if to say, 'Don't talk, don't talk!' The second film that affected me that way was A Clockwork Orange, which I saw in the theater 40 times. My background is in animation, and Marc Caro was a comics designer. In a way, we were somewhat like Terry Gilliam in our visual sensibilities on the two French films we did together. We like pictures and compositions. I can't imagine doing a film without paying attention to composition. It's by instinct, I don't think about it. If I think a shot is ugly, I throw it in the garbage in the editing room. Even though I did Alien Resurrection without Marc, I think this film is very close to our movies in terms of its [visual] aesthetics."

With myriad considerations involved in mounting a huge special effects-laden, sci-fi/action film — not to mention the struggle of communicating with a mostly American crew in his modest English — Jeunet decided to storyboard the entire picture to give everyone a visual basis from which to work. As Khondji explains, "Working with Jean-Pierre, you really do use the storyboards, although he doesn't want them treated like a literal bible. He wants the crew to imagine beyond the storyboards. There are elements regarding the sets, props and costumes that are not exactly described or even mentioned in the storyboards. But we'd use them for the framing of shots, because he has very definite ideas about how he wants the shot to be framed and which [aspects of the story] you need to tell with the frame."

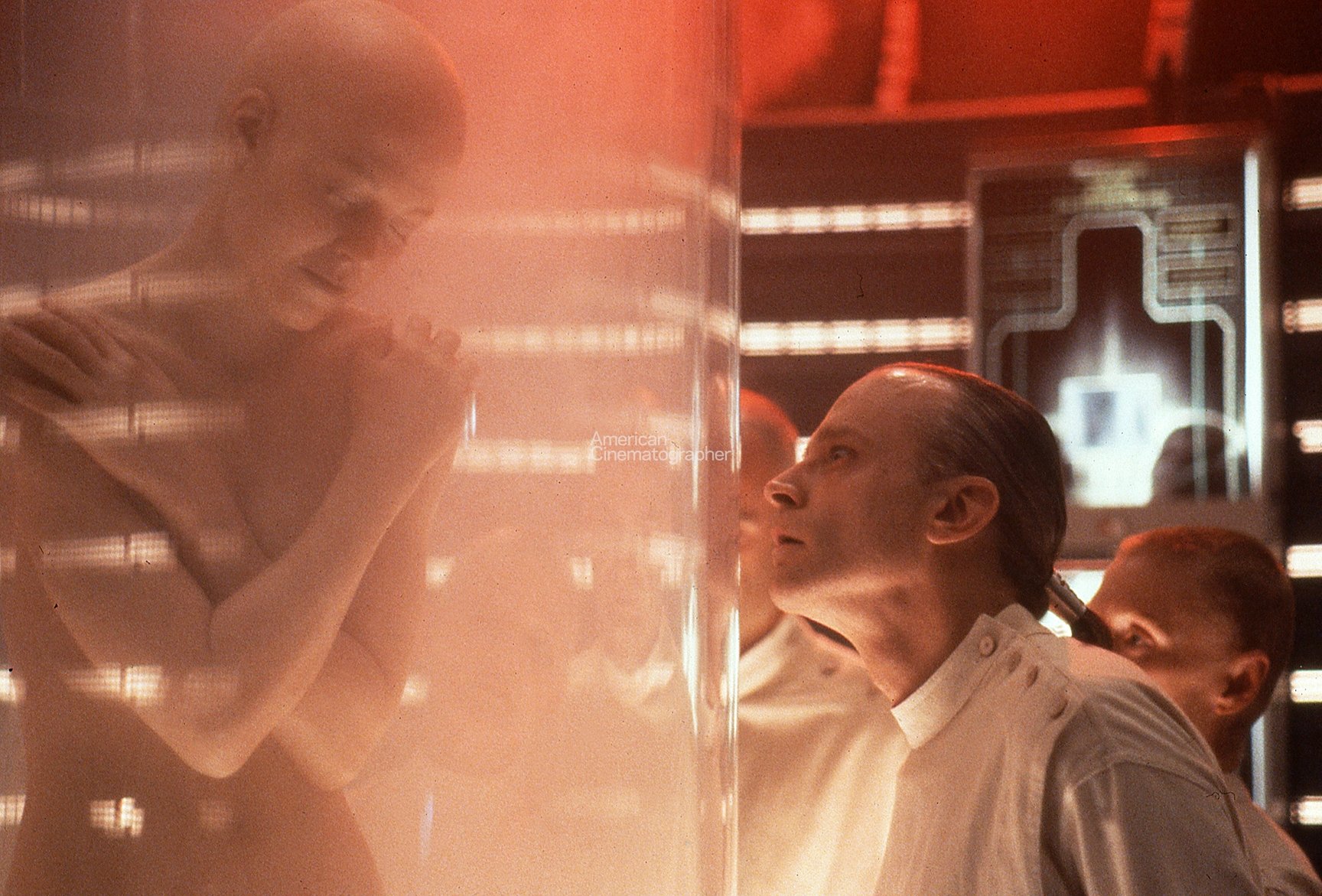

Special care was also taken in designing any shots involving the aliens. "Jean-Pierre rehearsed everything that involved them with a video camera masked to a 2.35:1 format — all of the aliens' positions and movement," Khondji recalls. "Everything was planned beforehand to try to film them in a different way. Watching him work with the alien creatures — long before principal photography even began — made me think of a choreographer working with dancers."

"To save time on the set, I did all of the rehearsals with Pitof, the visual effects supervisor," Jeunet elaborates. "I then made a video print of every shot and had them in a notebook. It's very difficult to shoot a man in a suit and make it convincing. If you move a little bit too low or too high, it's a man in a suit — it's not an alien. This strategy was also a great help because Pitof directed many of the alien scenes for the second unit with [A-camera operator/second-unit cinematographer] Conrad W. Hall."

During their preparation, Khondji and Jeunet thoroughly reviewed the previous Alien films to gather insights into how their predecessors approached their respective entries in the series. The duo also consulted many other science-fiction and horror film classics. "Jean-Pierre and I watched an incredible number of films," says Khondji. "I was actually very interested in B-movies, especially the science-fiction films of the Fifties. Although they're not always well done, they can be almost haunting. That element was very important to me for Alien Resurrection because I wanted the film to feel haunted. I wanted the sets and the ship to be haunted by the evilness of the characters within them.

"I also liked doing the gore effects in the film, but I don't like lighting them and making them too obvious. I love it when things are really horrible but backlit, dark and silhouetted. Then the imagery is more a product of the audience's imagination rather than what is on the screen. I find that people can imagine much more than you can ever get on a negative, and you free people's imagination by not showing them certain things. That's a very important aspect of all of my work in general. I don't make the imagery dark just out of the pleasure of making it look good; in a way, [by keeping aspects of the imagery obscured], I give the audience something more to look at."

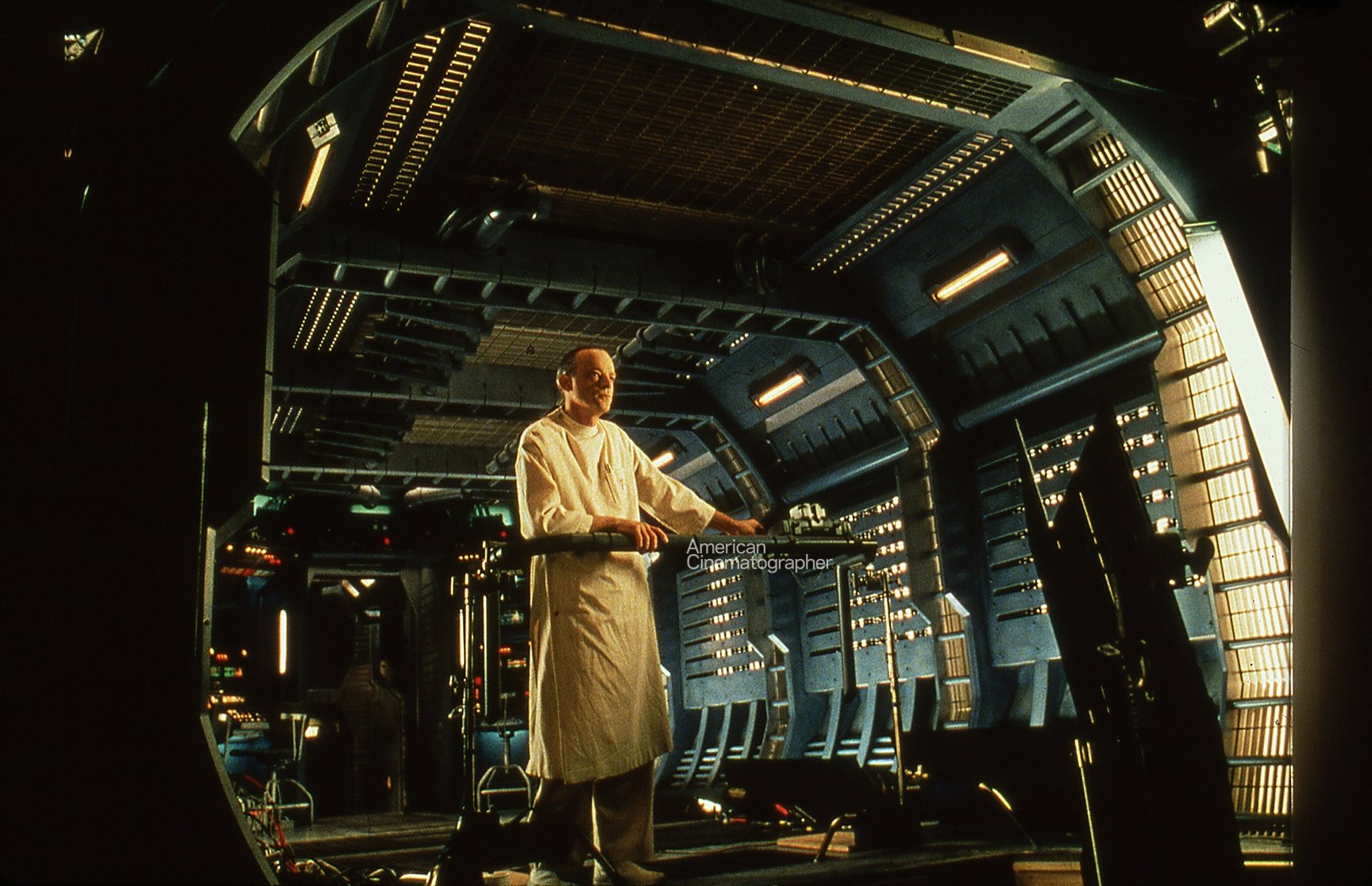

Alien Resurrection takes place entirely in outer space on two crafts: the Auriga, a massive and brooding space station aboard which Ripley and the aliens are experimented upon; and the Betty, a small, brightly colored renegade ship used by smugglers who board the station. Designed by Phelps, the often-cavernous sets depicting the interiors of these two vessels were realized on the Fox soundstages in Culver City.

In determining a lighting approach for the futuristic locales, which primarily consisted of seemingly endless corridors, Jeunet, Khondji and Phelps worked in tandem to integrate as much lighting as possible into the set design, often employing glowing panels behind built-in gratings and cosmetically enhanced Kino Flo fixtures built into walls and ceilings. Notes Khondji of this approach, "Nigel [Phelps] built the lighting into the structures so that it followed the contours of the sets, almost as if the lighting were etched or engraved into the design. The set's [integrated] lighting made it appear as if it were a living, breathing creature. On wide shots, it almost looked as if we were inside some cavernous animal or dinosaur. The sets became characters in themselves."

Adds gaffer Chris Strong, who helped Khondji illuminate Seven, "To be able to see and photograph the sets, the majority of the floors were made of metal grating backed with Lee 129 Heavy Frost diffusion and quarter CTB, with 2K nook lights hidden underneath. We had about 250 of them on the main set alone, all tied into a dimmer board. The ceiling was also grating backed with diffusion, behind which we had hundreds of bat strips — strips of wood with porcelain sockets and 211 PH bulbs — which were also tied to the dimmer. For high ceilings, we used chicken coops and 10-light cyc strips for more punch. The set walls also had ribs — periodic panels behind the grating — that went around some of the hallways, which were lit from behind with 211s on bat strips. We also had clear 60-watt Lumaline bulbs [16" clear tubes visibly mounted on the walls] periodically built into the set walls down the big corridors. They were dimmed way down to just a glowing filament as a design element. Every light was individually dimmable, and we had about 550 different dimmer leads on the main hallway set alone.

"In some of the hallways, we had Kino Flo tubes running underneath the base edges of the grated floors. We didn't dim the Kino tubes on a dimmer channel, but we'd sometimes throw some neutral-density gel on them or use streaks and tips to knock them down a bit." With the majority of the lighting provided by these built-in practicals, Khondji would then supplement light on the actors with more controlled, modeled sources, using individually set Kino Flo units. "The whole look of the film can be viewed as a blending of design and lighting," says Khondji. "The production thought we were spending too much money building the lighting into the sets. Perhaps it was unusual to work that way, but it gave us a lot of freedom to move about and work very quickly between setups. In fact, we could make a set look like a completely different set just by a change in the built-in lighting scheme. Chris Strong would adjust a few channels on the dimmers, turning a high-key set into a low-key set. We'd then wet the set down, make it oily or gritty, and add smoke; it would become a completely different place, but with an almost subconscious suggestion of a place we've been before.

"We came up with a lot of different lighting schemes so that viewers wouldn't be able to tell that they'd been in the same hallway 15 times," Strong details. "We'd often take the diffusion paper out from under the floor at the edges, so we'd get hard shafts going up the walls and still have soft light underneath the actors. We had a video tap monitor in the dimmer room so that the dimmer operator could see exactly what was happening on the set. Then, for every slate number shot, he'd enter the exact lighting settings for each take into the board's memory. With the exception of any lights we had on stands on set, every light setting could be exactly recalled for any given shot. We did use some incandescent light on the sets, but not much. Darius preferred the Kino Flo look."

Khondji adds, "Topping all of that off was the use of the ENR process. It was like cooking — you put in all of these different ingredients and make this sort of weird witch's brew that becomes the look of your film."

![Jeunet added menace to the aliens by giving them the ability to spit acid at their prey. Commenting on the film's horror aspects, he says, “I have no idea [how to go about scaring audiences], because I'm never afraid in a theater. I can't imagine how you can be afraid in the theater, but during test screenings, I saw men — and especially women — jump out of their seats. So I think I did okay."](/imager/uploads/463920/Alien-Resurrection-1_6c0c164bd2b597ee32b68b8b5755bd2e.jpg)

Executing such a high level of lighting/production design integration required the filmmakers to utilize a full-time rigging crew to install and wire the vast network of sources and cables before the main unit would walk onto a set. Explains key grip Alan Rawlins, "Even with the large stages we had at Fox, our main concern from the beginning was that we were very cramped and fighting for space for the rigging. With the bulk of our lighting coming from underneath, from above, or from the sides of the sets, it became quite a feat just to keep everything separated and find space for it while making it all work together. We also utilized a lot of little pieces of the sets that were actually working as rigging or built-in lighting apparati. Chris Strong and I — as well as rigging gaffer Bill McKane and rigging key grip Bob Leitelt — put a lot of thought into this to achieve the look and stay functional enough to be able to pull the project off. Bob and Bill were definitely our right and left hands in terms of keeping us prepped ahead of time. When we'd walk off one set and onto another, the rigging crew would have done a fantastic job and we'd only have to make a few minor changes to be off and running."

Taking full advantage of the versatility that the dimmer-controlled lighting offered the production, Jeunet and Khondji mapped out a visual flowchart that detailed how the lighting should transform to reflect the film's increasingly intense narrative. The cinematographer explains, "We established a scale from one to five; it began with almost no lighting effects or movement, and became complete lighting chaos. The lighting got a little stronger in levels two and three with some flashing and warning lights. Level four was a more frantic state of alarm, with strobe lighting and gyrating sirens. By level five, everything was a complete frenzy of lighting and camera vibration — going to an almost completely blurred image due to all of the shaking."

"The lighting was 'normal' up until the point when the aliens escape," expands Strong. "At first, we'd just have flashing red lights. Then we'd add panning Xenons and these strobe lights on the tops and bottoms of the hallways. The strobes were four-foot tubes with several small daylight-balanced lights inside and down the length of them. We then could strobe in sequence either at us or away from us. We also had steam, smoke, sparks, cracked oil, liquid nitrogen, and wind effects for added visual energy — you name it, we had it.”

Given Jeunet's affinity for wide-angle lenses, it's not surprising that Khondji chose to build his lighting into the sets when possible. With masters being photographed on 14.5mm, 17.5mm and 21mm lenses, virtually the entire set could be visible in any scene. "I love using short lenses," Jeunet confesses. "On this film, for the first time, I did use some slightly longer lenses — not to be more American [in my shooting style], but because sometimes it's useful to have more [cutting] material. On Delicatessen and The City of Lost Children, I used the 18mm and 25mm lenses all the time. On Alien, I often used a 14.5mm. For me, any lens after a 25mm is a long lens. When I put on a 35mm, it's a long lens, but that's also because I like to be very close to the actors. I love when an actor approaches very close to the lens. However, the main problem in using short lenses is that in each shot you have a lot of set to light. So you have to be patient with the lighting. Darius has a very picky eye like I do; sometimes it's tough to work with someone who has a picky eye for the light, because you have to wait — and like all directors, I hate to wait. When you work with Darius, you know you may have to wait some, but you also know that the results will be very nice."

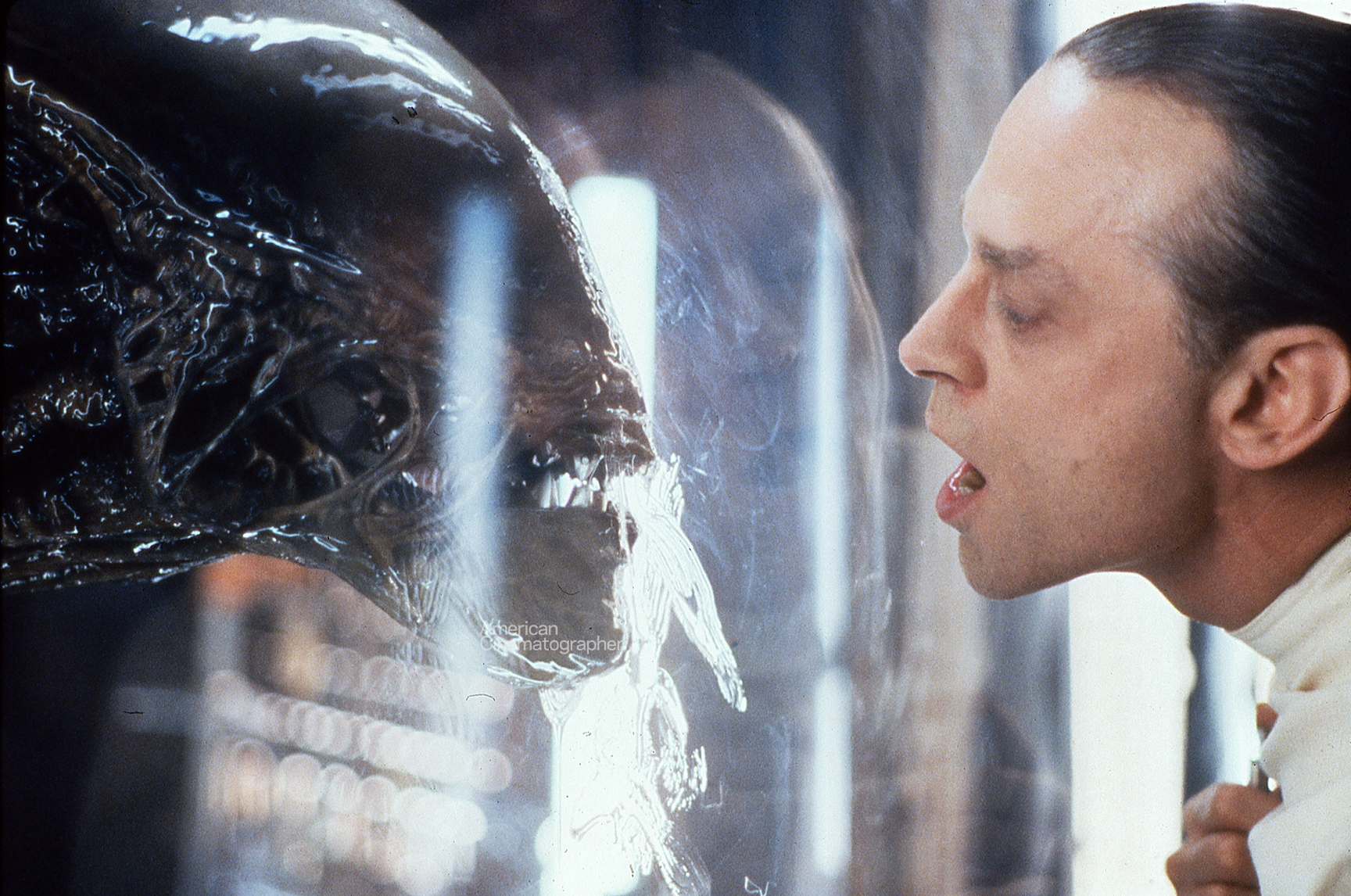

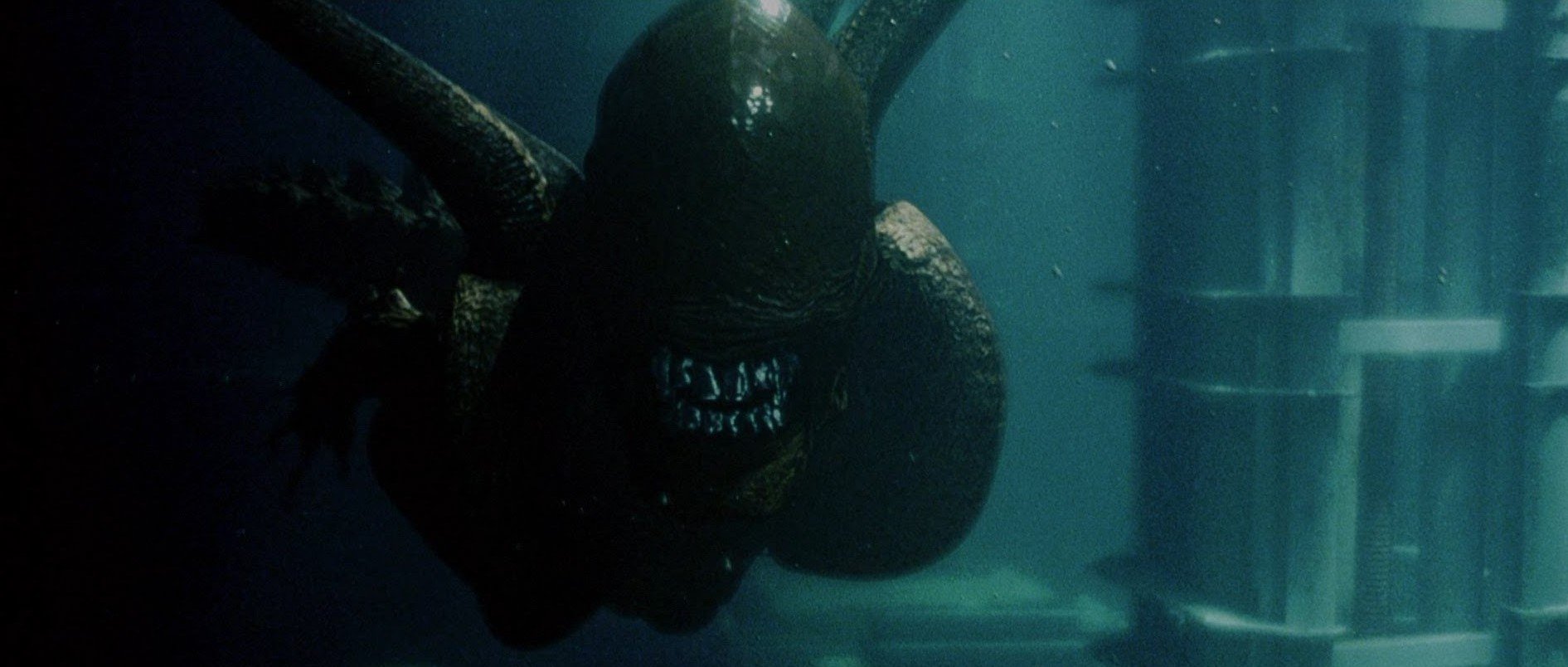

In order to illuminate the aliens themselves, Khondji devised a specific lighting treatment to add even more menace to the already abhorrent creatures. "I lit the aliens almost exclusively with reflections of fluorescents," notes the cinematographer. "I had them constantly wetted with [methyl-cellulose] goo, and then we basically built a cage of Kino Flos around them to create reflections in the moisture. Also, I'd often add a little green to the aliens' lighting. You couldn't really tell the color is there, but it had an effect. I love the color green. I find it very sensuous in a way, and I think the aliens have a kind of a sensuous design as well. They're the essence of evil, but there can sometimes be a sensuousness in evil.”

“I’ve found that making films is often close to making love in terms of pleasure and intimacy. I’ve never really discussed this point in an interview, but it’s very important.”

"I've found that making films is often close to making love in terms of pleasure and intimacy,” Khondji says. “I've never really discussed this point in an interview, but it's very important. When I look at paintings in a gallery or museum — especially Italian, Florentine, Renaissance and primitive paintings — there's something very sensuous and sexy emanating from them. I've always found the experience very exciting and arousing. I think the same sort of thing happens when you play with light — studying people's faces and bodies — and illuminate a set; there's something extremely exciting about it. Cinematography often forces you to look at something more closely and really examine its features. In doing so, you become much more connected to the inner essence and beauty of that person or object. It's a very intimate exchange between the light and the subject."

"The aliens went almost totally black once they had the slime on them," expands Strong, "So, just as you can't 'light' a black car — you reflect light onto a black car — we reflected Kino Flos onto the aliens, which were mostly lit with several single daylight tubes. Additionally, we'd sometimes use a harder light to backlight the steam or drool coming out of their mouths. There, we'd use a small tungsten unit for the backlight, because a Kino Flo isn't really hard enough to do the job."

For scenes in which Ripley is in close proximity to the aliens, Khondji was presented with a problem that yielded a fortuitous solution. "The lighting for the alien was completely different than the lighting for Sigourney Weaver," submits Khondji. "The difficult part was finding a way to light her differently than the alien, even though they were interacting together within a shot." Considering Ripley's duplicitous character and mysterious agenda, however, the photographic predicament actually added subtext to the character's lighting in those instances. "I decided that I would sometimes light Sigourney closer to the way I did the alien. I would have her skin wetted to make it look shiny and then use fluorescents to create reflections around her arms and face, underexposing slightly. This gave a strange texture on the skin that is reminiscent of the way the alien looks."

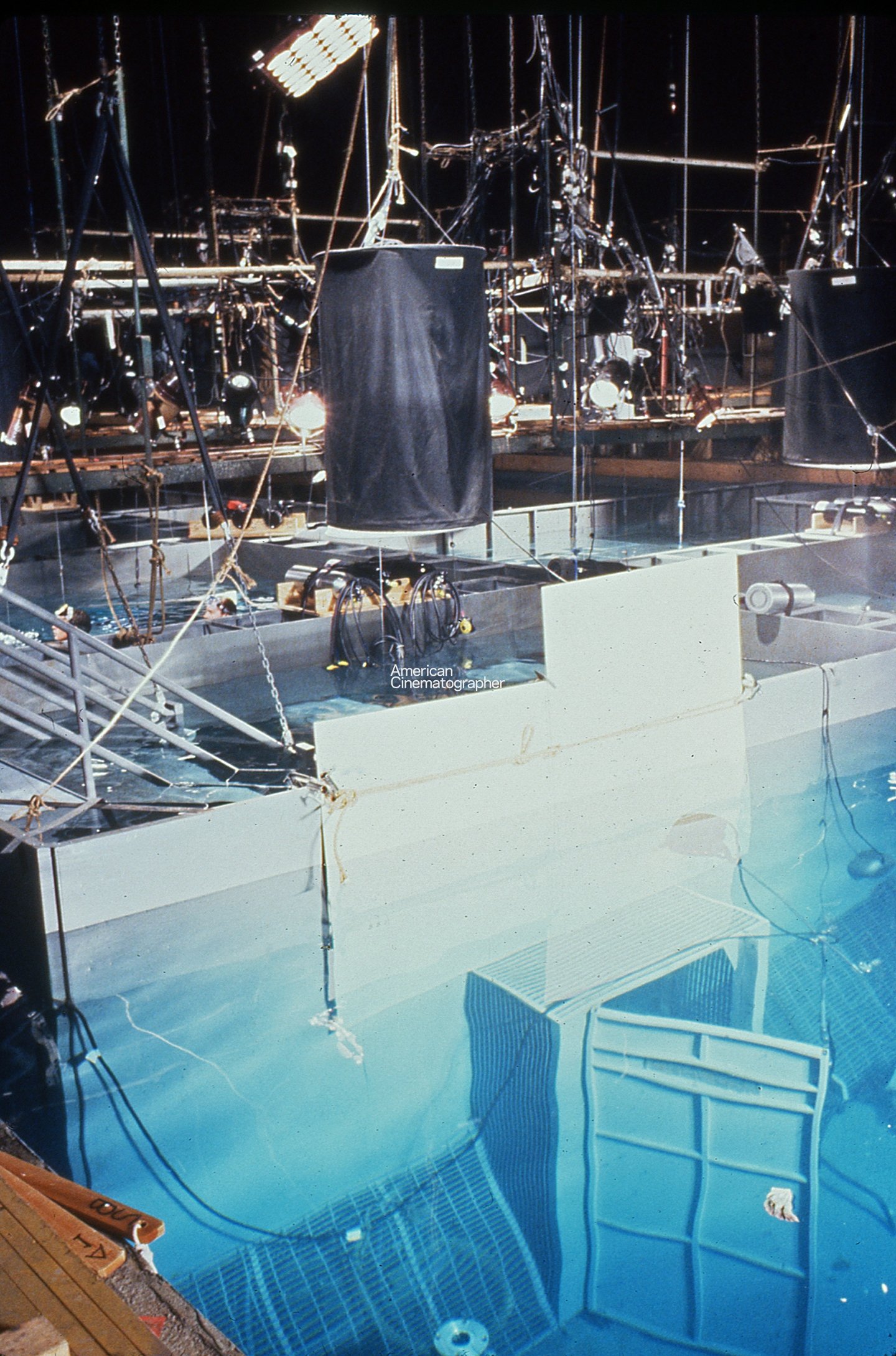

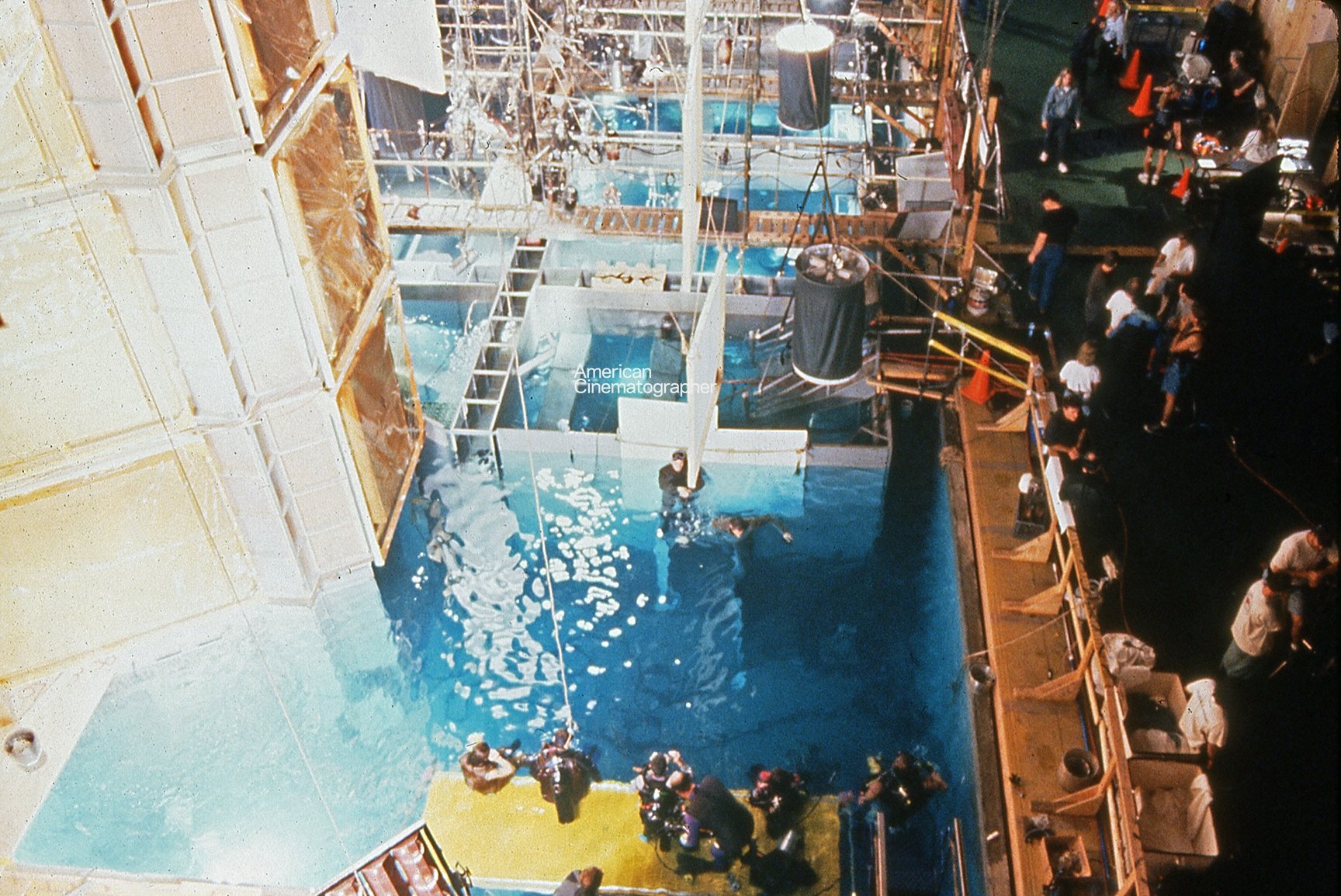

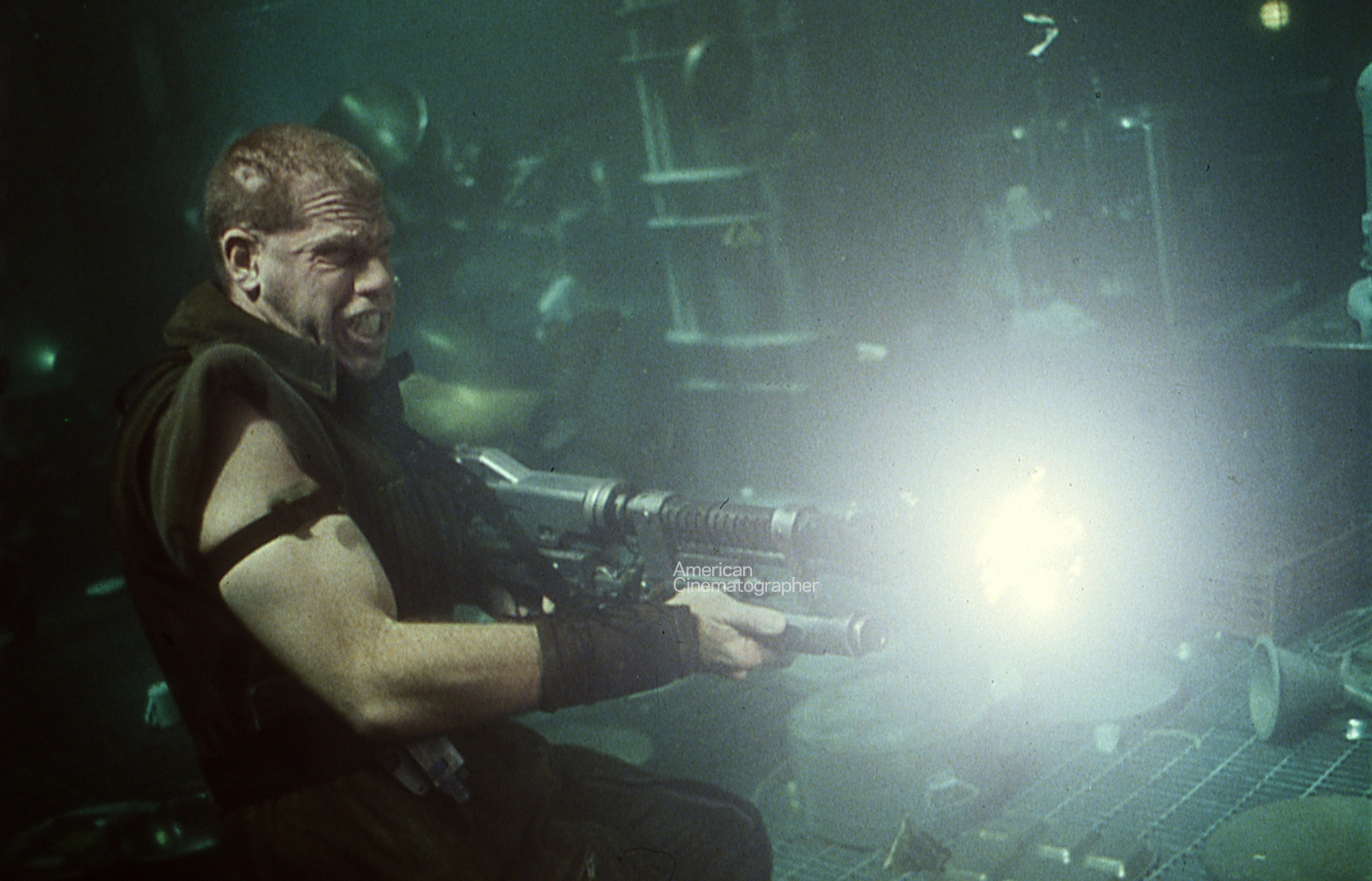

A particular challenge for the entire crew was filming an extensive underwater chase sequence that takes place in the Auriga's flooded kitchen. Khondji — who got his diver's certification before shooting The City of Lost Children in order to operate during the film's underwater sequences — worked with veteran underwater director of photography Peter Romano to tackle the physically draining three-week submerged shoot.

“I tried to keep the underwater lighting more clair-obscur — which means clear and dark in painting terms — by creating light and dark areas underwater, which is very difficult because water spreads light very quickly."

"We had several discussions about the lighting and how much you would see underwater," explains Khondji. "We wanted to have the freedom to shoot the chase almost in a choreographed manner with two underwater cameras. So I decided to utilize overhead lighting, making shafts of light using virtually no fill at all and underexposing a lot. The only lights I would actually bring into the water were these new underwater Kino Flos — built by Peter Romano's company HydroFlex and Kino Flo — which could be used to add some half-light fill on an actor's face, making one side go completely black. I would also use the Kinos near the camera to bring light into the actors' eyes as they swam through frame. I tried to keep the underwater lighting more clair-obscur — which means clear and dark in painting terms — by creating light and dark areas underwater, which is very difficult because water spreads light very quickly."

Explains Strong, "The kitchen and all of the underwater sets were lit from above the water with 1200-watt ACL Pars on scaffolding shooting down into the water. They were used to edge the actors as they swam through different areas, as well as to highlight certain parts of the kitchen — metal support pillars, chrome appliances, utensils, etcetera. The Pars weren't totally directional because the water did disperse the light, so they naturally lit other areas. However, the 1200-watt ACLs — basically aircraft landing lights made with clear glass, which have very hard mirrors behind them — are very spotted and directional, so they had a better chance of reaching straight to the bottom of the set [than a normal Par light]. We ran AC for the majority of the underwater shooting, but we did have everything ground-fault interrupted [GFI] so that if anything ever fell in the water it would trip immediately."

The intense underwater chase leads Ripley and her cohorts into a flooded elevator shaft with their xenomorph pursuers right behind them. Approximately 30’ tall, the six-sided elevator shaft was lit by a series of Maxi-Brutes and Dino lights suspended from the permanents by chain motors, which illuminated modular 4'x4’ frames of 129 diffusion and quarter CTB that could be affixed to the side panels. The water at the bottom of the shaft was illuminated with individual 10K bulbs to provide a ghoulish blue-green glow; these were run on DC power due to safety concerns. "We designed that set so that whenever we opened up one side, all of the unnecessary lighting and frames could be sucked up out of the way to the permanents on taglines through a pulley system," says Rawlins. "We usually used about three different layers of gel. One layer of diffusion was built in the frame that mounted directly on the set. Then, hanging outside the set, another layer of diffusion was used to soften the light even more. There was a layer of color hanging in front of the lights as well.

"Additionally, we worked with the set designers to make sure that we could pull two of the sets' walls completely out to make a path for the 31’ Technocrane which we had mounted on a Titan crane. I believe that was the first time anyone had put the larger Technocrane on a Titan. We went through a lot of research with Chapman and Technocrane to make sure that we did not exceed the specified weight and safety limits set by Chapman."

Both Khondji and Jeunet are pleased with their experience on Alien Resurrection, and they believe that they have delivered a fresh perspective on the series. Asked if his shooting style has a consistent methodology, Khondji offers, "I don't want to have one set method that's always fixed throughout my films. When I walk onto a set or a location, I already have the mood of the scene in mind, so I try to adapt that to the set or location. However, when I visit a location, there are actually two things that may effect how I shoot there. First, I may be inspired by the location itself. And second, sometimes the ambiance of the location's natural lighting may bring out a certain quality. When you visit a set, it's much more of a constructed, planned world, so you rarely have as many intuitive and instinctive emotions. By that point, I've already done a lot of planning with the designer, so I usually know beforehand how it's going to look and be lit.

"I would like to think that my methods change according to the director that I'm working with and the story that I'm telling visually," he concludes. "I always try to stick with the director and really become his friend. I try to understand what he has in mind and what's important in the story. And then I try to work with the actors almost as if I'm another actor on set, performing through my work."

Khondji was later invited to become a member of the ASC.

The cinematographer was honored with the ASC International Award in 2023 for his outstanding career. You can watch the entire ASC Awards ceremony below. Khondji's introduction by director Alejandro G. Iñárritu and his acceptance speech starts at 1:07:00:

Author Christopher Probst became a member of the ASC in 2018.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.