Moon Walk: First Man

Linus Sandgren, ASC, FSF and a team of collaborators across departments re-create Neil Armstrong’s journey from the Earth to the moon for director Damien Chazelle.

Unit photography by Daniel McFadden, courtesy of Universal Pictures and DreamWorks Pictures

On July 21, 1969, astronaut Neil Armstrong became the first human to set foot on the moon. The historic moment represented a huge milestone for mankind — and it was also the culmination of a massive succession of technological breakthroughs and personal sacrifices. Director Damien Chazelle and cinematographer Linus Sandgren, ASC, FSF capture that story in the biopic First Man, which follows Armstrong (Ryan Gosling) from 1961 through the successful mission in 1969, in the process chronicling the advances and setbacks in NASA’s manned space program during that span.

Sandgren remembers that his introduction to the project came during production of his previous collaboration with Chazelle, the musical feature La La Land (AC Jan. ’17), which earned the pair Academy Awards for cinematography and directing. “Damien talked about it and asked if I wanted to be involved, and of course I did,” recalls Sandgren. “It was a very interesting project and also quite different from La La Land. It was fun to see how Damien evolved from a musical world. He’s very meticulous with the details — the art department, costuming, etc.”

Chazelle relates that First Man’s producers initially approached him about the project shortly after he’d finished the feature Whiplash (AC Nov. ’14), “and we started putting the pieces together during La La Land. What really attracted me was the ‘mission movie’ aspect and [the opportunity to] strip away the mythology to tell a very you-are-there ‘documentary’ from the point of view of the person who actually experienced it.”

Closer to production, the director adds, “We set up a screening series for the crew to take inspiration from movies of the era — like Gimme Shelter, Red Desert, Cries & Whispers, Cassavetes’ films, etc. Each had a stylistic connection to what we were trying to put on film.”

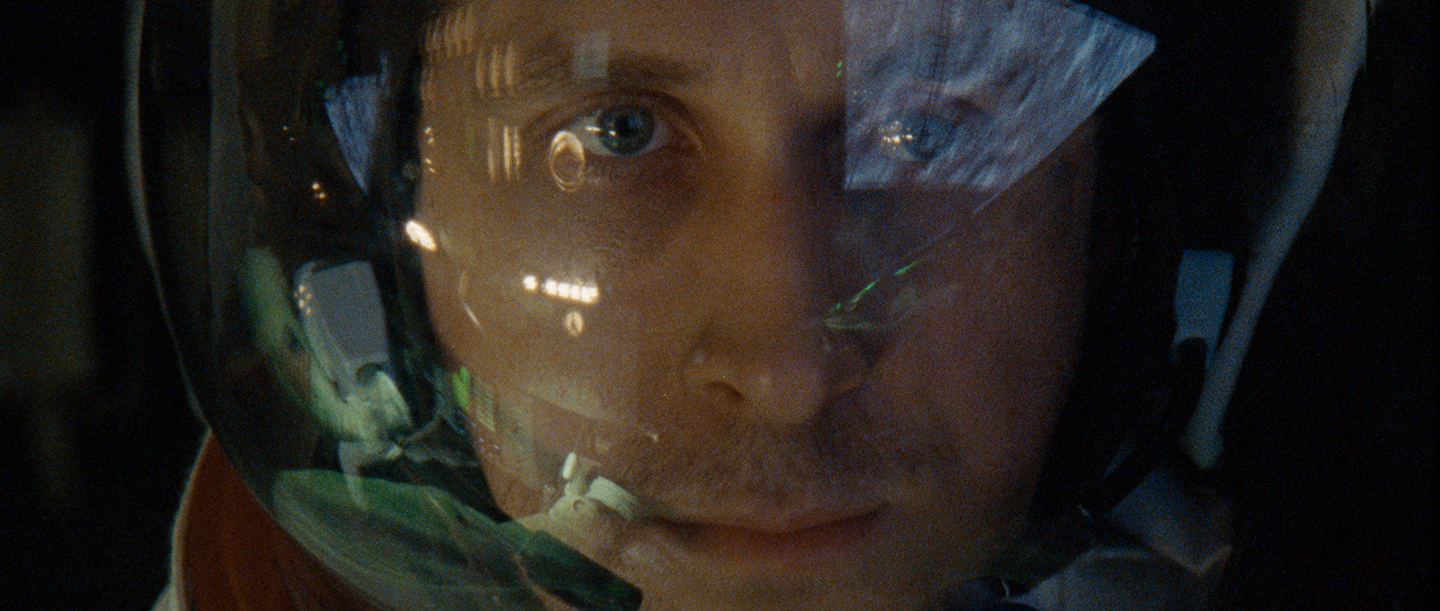

“Damien wanted to take a very different visual approach from what we did on La La Land,” Sandgren shares. “Initially he said, ‘Let’s do this whole film handheld, maybe Super 16, gritty, immersive and very realistic.’ He wanted to embrace a documentary aesthetic because the movie is all about feeling the challenges of the missions and how fragile and claustrophobic the spacecraft really were — and there’s also a great focus on the families of the astronauts and the sacrifices they all had to make for this space mission.

“We found inspiration in films like The Battle of Algiers by Gillo Pontecorvo, but also — thematically as well as in the lighting and composition — in the films of Alan J. Pakula and Gordon Willis, ASC,” the cinematographer adds. “We ended up with a kind of neo-noir, cinema-verité style combination.”

“I wanted the lighting in the film to be grounded in reality. I wanted to use natural, realistic lighting, including warm practicals, dirty-green cool-white fluorescents, mercury vapors and naturalistic sunlight. [For scenes set] in space, we always used only one single lamp, simulating the sun, in combination with the practical lighting in the spacecraft.”

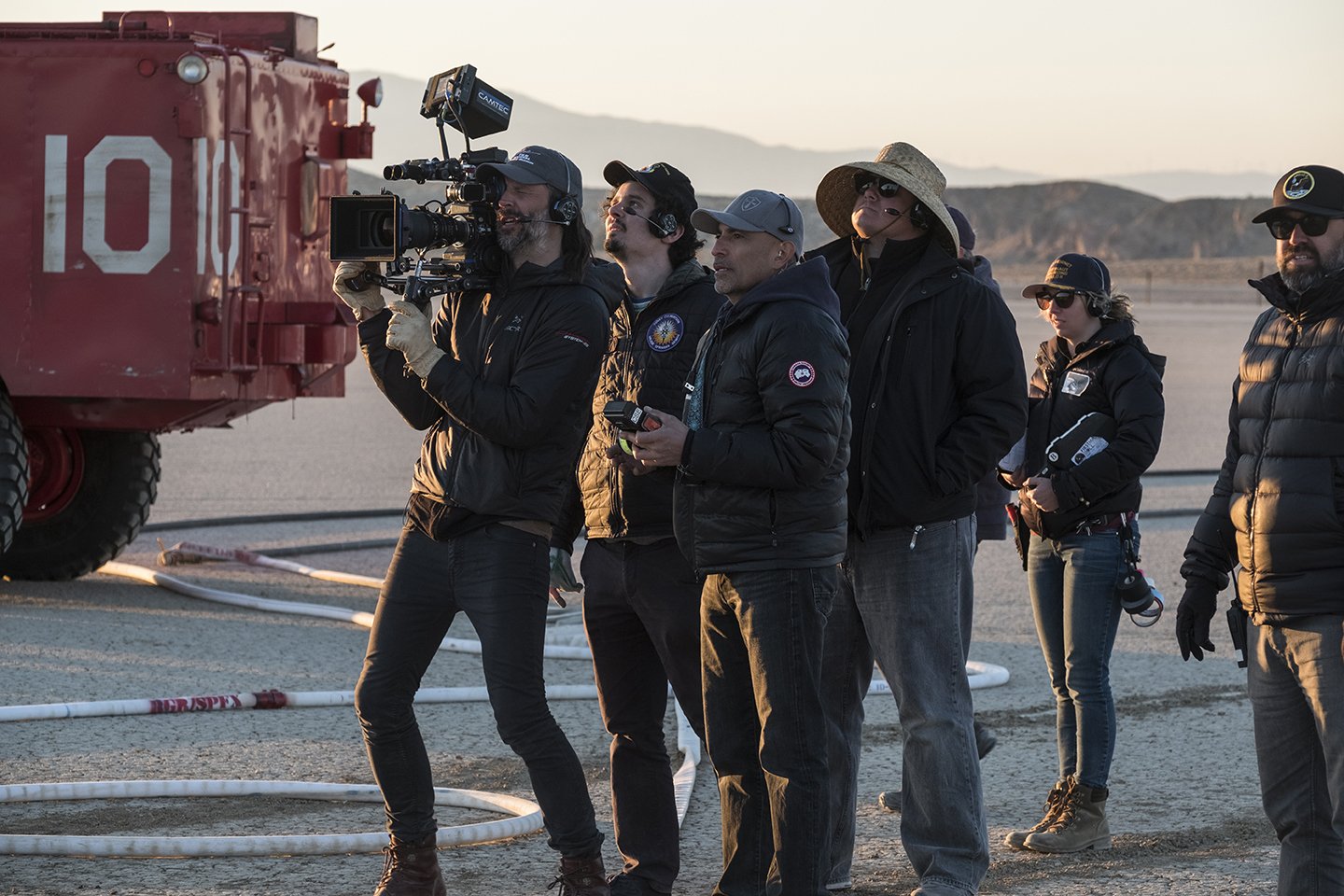

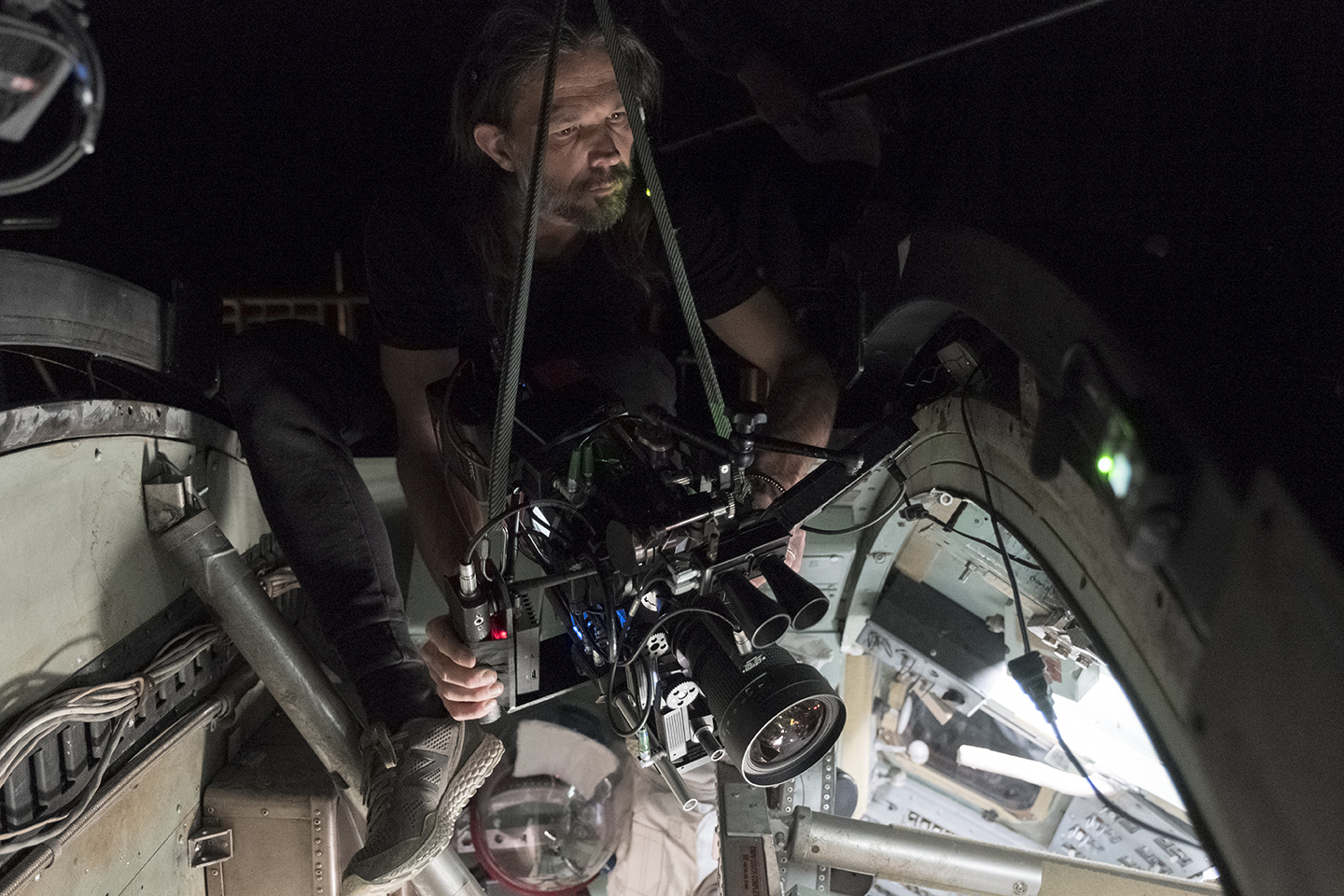

Following a battery of camera tests, Sandgren deployed a mixture of Super 16mm, 35mm and Imax cameras to capture the documentary feel and realistic space sequences Chazelle sought. “We shot almost the entire film handheld, and we found that we had an opportunity with the mixed film formats to visually express the human emotions of the story in an immersive way,” explains the cinematographer, who sourced the camera and lens package from Camtec in Burbank and Atlanta.

“We wanted the first period in the story to feel emotionally raw,” he continues, “so we covered those scenes in Super 16mm [2.39:1] with Kodak [Vision3 50D, 250D and 500T] 7203, 7207 and 7219 — and for wider shots we changed to 2-perf 35mm with Kodak 5207 and 5219. We found that the Super 16mm 7219, when processed normally but rated at 250 ASA, gave us the right texture for the period as well as for the intimacy of the scenes inside the spacecraft. But the exteriors of the spacecraft called for more detail, so we shot those in 2-perf 35mm with 5219 pushed one stop.” Camtec confirms that all of the cameras — 2-perf, 3-perf and 4-perf — were centered for Super 35 gates.

“When the family moves to Houston, we used only 2-perf 35mm 5207 and 5219 for the scenes on Earth,” Sandgren notes. “We pushed the film one stop in the NASA world for more contrast and grain, and we pulled one stop in the family environment for less grain and softer contrast.”

For the Super 16mm portions, the cinematographer details, “we used an Aaton Xtera, Arri 416 and Aaton A-Minima, with Canon 6.6-66mm [T2.7] zooms, [Arri/Zeiss] Ultra 16 primes, and Kowa Cine Prominar [spherical] primes — all cropped for 2.40:1. We shot most of the main-unit 35mm with Aaton Penelope 2-perf cameras and Arricam LT 2-perf cameras, using Fujinon Cabrio 19-90mm [T2.9] zooms, [Camtec Vintage Series] Ultra Primes, and Kowa Cine Prominar spherical primes. The miniature unit, stunt unit and second unit also used 3- and 4-perf Arri 435s, and 8-perf VistaVision cameras.

“I wanted the lighting in the film to be grounded in reality,” Sandgren adds. “I wanted to use natural, realistic lighting, including warm practicals, dirty-green cool-white fluorescents, mercury vapors and naturalistic sunlight. [For scenes set] in space, we always used only one single lamp, simulating the sun, in combination with the practical lighting in the spacecraft.”

First Man shot primarily in Atlanta, Ga. — on re-dressed practical locations and on stages at Tyler Perry Studios — from October 2017 through February 2018; the production also did some location work at Edwards Air Force Base in the California desert and at Cape Canaveral in Florida. Sandgren operated the A camera, and his main-unit team included B-camera operator Davon Slininger, 1st ACs Jorge Sánchez and Andy Hoehn, 2nd ACs Melissa Fisher and Paul Woods, loader Will Whittenburg, gaffer Stephen Crowley, and key grip Anthony Cady. Other key collaborators included production designer Nathan Crowley and visual-effects supervisor Paul Lambert, as well as miniature-unit cinematographer Tim Angulo; stunt-unit cinematographer James King; splinter-unit cinematographer Mattias Rudh, FSF; and aerial cinematographer Dylan Goss.

“We wanted to capture everything in-camera, without greenscreen,” the cinematographer says. This dictum motivated the production to shoot with full-size spacecraft sets positioned in front of LED screens, thereby mitigating the need for postproduction compositing; whenever possible, the filmmakers also favored miniatures over CG aircraft and spacecraft.

“We basically wanted to use the LED screen and the motion base as a flight simulator. In order to get a realistic depth of field, we found that a 30’ distance to the camera would be best, since 30’ is very close to the infinity focus mark on the lens.”

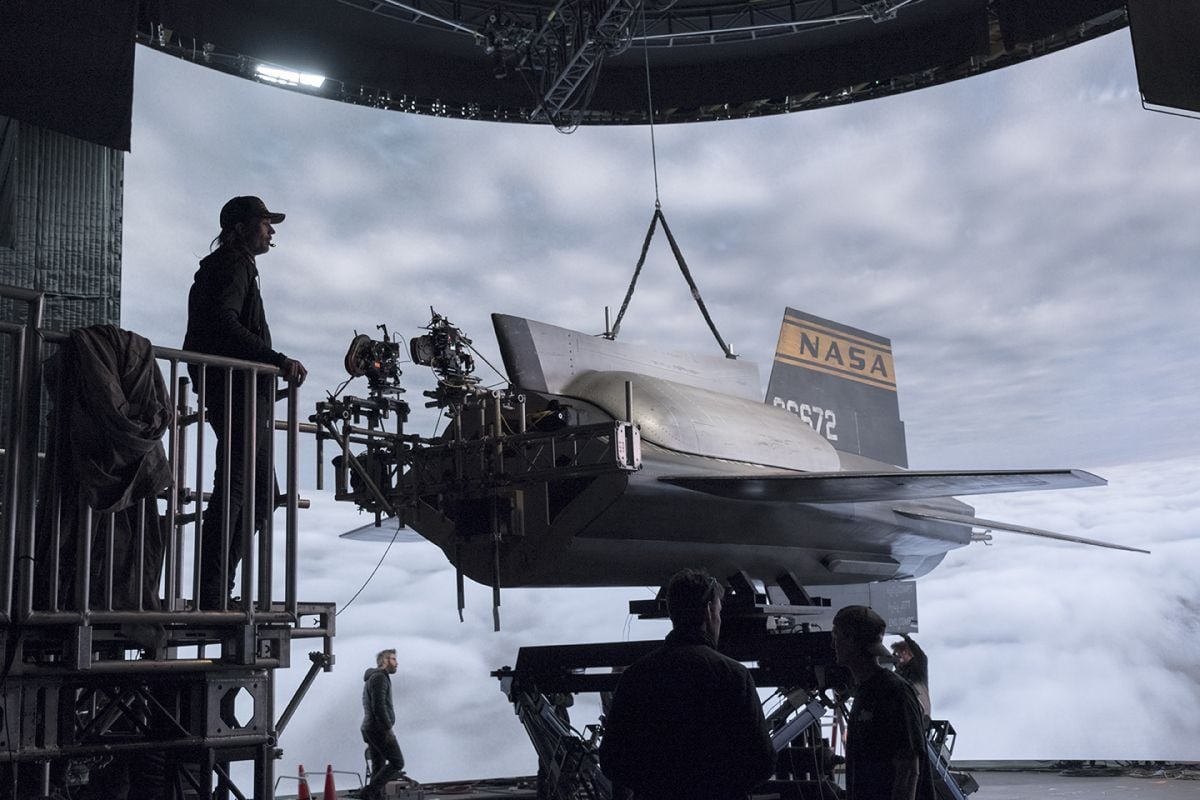

The movie begins with a harrowing sequence in which Armstrong pilots the experimental X-15 rocket plane. After reaching an altitude above 207,000' and experiencing zero gravity, Armstrong has to fight for control of the aircraft when it “bounces” off the atmosphere during its descent and balloons back upward. To capture the flight, Gosling worked through long takes in a full-size X-15 cockpit mockup that was mounted on a motion base in front of an LED screen that displayed immersive flight footage.

Working in collaboration with Fuse Technical Group and VER, creative producer and technical consultant Fred Waldman of the Visual Integration Department spearheaded the development of the LED screen, which he describes as “a large wall, approximately 34’ tall and 100’ in linear length curved onto a 60’-diameter [partial cylinder]. We sourced the ROE Visual 2.8mm-pixel-pitch screens from Fuse and did a lot of testing to make sure we wouldn’t pick up a moiré pattern off the screen, either directly from the cameras or after going through the film scanner, and give away the effect.”

Sandgren adds, “We basically wanted to use the LED screen and the motion base as a flight simulator. In order to get a realistic depth of field, we found that a 30’ distance to the camera would be best, since 30’ is very close to the infinity focus mark on the lens. Also, the size of the screen helped us to get a realistic light effect. With a spot meter [set to] 250 ASA, it measured f81⁄2, and it gave an incident light on the craft of f8 — a loss of only 1⁄2 stop — which [provided] very realistic light effects.”

“We also sought a single media server capable of six 4K outputs for the 12,288-pixel-wide canvas,” Waldman notes. “Additionally, the server had to be genlocked to a variety of film cameras, support high-quality codecs, and integrate VFX workflows — just to name a few [requirements]. We couldn’t find anything existing on the market that accomplished that, so we built our own custom media server. Not everything was pure video footage. We also had up to 32K-resolution stills and spherical imagery that we could move around on the screen live. We used lower-resolution proxies for footage intended to be caught outside of direct camera view for reflections or as lighting effects.”

“The X-15 cloud fly-through footage was all computer-generated in [Planetside Software’s] Terragen, a procedural environmental application,” reveals Lambert. “Our footage was rendered at various resolutions between 4K and 10K, and exposed and integrated into the background.” He adds that a lighting rig was set up outside the cockpit to allow for the interactive placement of a 5K PAR with dichroic lenses to represent the sun. “The light feels like strong, real sunlight [as opposed to] a film light clamped onto a piece of CG. The idea was to create a complete environment for the X-15.”

Special-effects supervisor J.D. Schwalm as well as Steve Rosenbluth at Concept Overdrive were also integral to the design and operation of the motion bases that supported the aircraft and spacecraft in the X-15 and other sequences. “We were able to tie our video system into the analog data coming from the base and derive a homemade flight simulator,” Waldman explains. “The LED screen itself was articulated and could bank in synchronization with the footage and the cockpit to make it look as though it was doing a much steeper dive in-camera. It was pretty dramatic to see Ryan sit inside those ships for 10 hours a day getting his butt kicked.”

This LED-screen and motion-base technique was applied for all of the movie’s flight sequences, which chart the progression through Project Gemini to the Apollo 11 spacecraft that eventually makes the voyage to the moon. To further enhance the in-cockpit visuals, Stephen Crowley notes, “We built a 9-light [Arri SkyPanel] S60 soft box to mimic the sky for all the flight sequences, and we incorporated 12-light Maxi-Brutes, fire-starter PAR cans and the interior practical console lighting. We were also able to feed media from the LED screen to the Arri S60 soft box to incorporate into our cues. We had LED RGB and bi-color ribbon in most of the practical lights on Gemini, Apollo 1 and Apollo 11; this gave us the opportunity to be in a basic blue-green standard work environment or to alternate between green and red as the scene dictated.”

Three years after being selected to join NASA’s Project Gemini, Armstrong makes it into space alongside pilot David Scott (Christopher Abbott) aboard the Gemini 8 spacecraft, which the duo successfully dock with an unmanned Agena target vehicle — the first successful docking between two spacecraft in orbit. To depict these and other spacecraft, the filmmakers worked primarily with a combination of full-size capsules and miniatures. “We ended up building the miniatures within the art department, as most of the miniature-effects shops no longer exist,” laments Nathan Crowley.

“I have used miniatures many times before, and they fit in perfectly with our ‘in-camera’ methodology,” the production designer continues. That methodology, he says, called for “full-size interior ship cockpits, full-size exterior capsules for fixed-camera docking sequences, miniatures for the mid-ground, and LED effects for the background. The capsules would be a traditional set build, but the miniatures would be 3D-printed. [For the 3D printing] we had 18 various machines, including two BigRep large-format printers, which could print objects [up to] 3’ cubed. We had three stages set up simultaneously that Damien could go between: one for full-size cockpit interiors, one for full-size exterior craft, and a miniature stage.”

Not all of NASA’s missions were successful. The greatest single tragedy during Armstrong’s tenure was the Apollo 1 capsule fire. An electrical short during a launch-pad rehearsal sparked a flame that quickly engulfed the pressurized cabin, claiming the lives of astronauts Gus Grissom (Shea Whigham), Ed White (Jason Clarke) and Roger Chaffee (Cory Michael Smith).

“That was a difficult scene to create,” says Crowley. “The event was shrouded in a mass of grief for NASA, making it difficult to understand how the Apollo 1 capsule had been set up. We rebuilt the Apollo 11 capsule with the Apollo 1’s complex door system, which was responsible for the astronauts’ inability to escape the capsule. We also replaced much of the plastics and electronics from the dashboards in the Apollo 11 set, and replaced them with metal to allow for [special effects] to burn the capsule safely. The Apollo 1 flash-fire happened in a matter of seconds, and re-creating this involved a lot of coordination between the practical-effects team, the stunt crew and the camera department.”

The filmmakers also took care with their stylistic approach for the film’s more domestic sequences. “One theme was to work with black negative space in the environments [used for] the drama on Earth, as a metaphor for death and as a foreboding for traveling into the blackness of space,” explains Sandgren. As an example, he points to the night scene when Armstrong sits at the kitchen table with his wife Janet (Claire Foy) and their children before leaving for the Apollo 11 flight. “The camera is quite far away and the other rooms aren’t lit, so the characters are surrounded by darkness. It serves as foreboding for what’s to come, but also shows the loneliness of [Gosling’s] character.”

“Linus referred me to the book Full Moon by Michael Light,” adds Crowley. “I had to constantly look at its photos to redefine how we should control the light and make the scenes roll off into dark infinity. A great example is a walk-and-talk scene we did in Neil’s neighborhood. We had seven condors that were all pointing into the set, and we didn’t light anywhere beyond the walk. We also had the streetlights shut off, so you felt a definite falloff to black and an ‘edge-of-the-moon’ feeling.” Armstrong’s Houston home was re-created by the production on location in an Atlanta neighborhood.

The Apollo 11 moon mission finally commences as Armstrong and fellow astronauts Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin (Corey Stoll) and Michael Collins (Lukas Haas) board a gantry elevator and ride to the Command/Service Module atop a massive Saturn V rocket, approximately the height of a 36-story building. Nathan Crowley and his team built the gantry-elevator set — “including the white room and the very top of the Saturn rocket that housed the Apollo capsule,” the production designer notes — at the Scherer Power Plant in Juliette, Ga.

The rooftop set for the gantry exit, Stephen Crowley explains, “gave us practical views of a lake that resembled Cape Canaveral. Every effort was made down to the smallest detail to match the feeling and environment of the real missions. I think we used one 12’-by-12’ greenscreen for one of the Apollo 1 shots; everything else was practical.”

To supplement the live action and miniature photography of the liftoff, Lambert incorporated actual NASA archival footage from the real launch. “Typical archival footage is under-cranked and degraded, but we received access to original NASA scientific camera negatives that have never been [publicly] seen before,” he reveals. “Everything was originally shot in a custom 10-perf 70mm square format. We composited that square into the center of the frame and then extended the sides out to the 2.40 aspect ratio with computer graphics.”

The crew relied on an array of techniques for shots of the astronauts in zero gravity as they journey from the Earth to the moon. “There’s a shot where Neil picks up a cassette and flicks it over to Buzz,” Lambert offers as an example. “It was on a fishing line they passed off to each other. So we had the real cassette in their hands, and then we transitioned to [and from] a CG version of the cassette while it floats between them. We also used CG to fill in holes in the capsules where the actors and objects were suspended from wires, and we even animated a few strands of hair to give the appearance of weightlessness.”

While the astronauts fly the mission, a group of controllers back at NASA’s Mission Control in Houston monitor flight operations. The Mission Control set was created inside an existing building in Atlanta. Crowley explains, “We lit Mission Control with only the practical fluorescent lights in the ceiling — 5,500K tubes with 1⁄4 Plus Green and 1⁄4 CTO in the control area, and the observation room was colored with Primary Red.

“The fixtures team and art department killed it here with practically operated console buttons and switches,” the gaffer continues. “We had two or three specific cues, but B-camera was always going around grabbing pieces. The lights were in place and functional, so the scene could run all the way through and we didn’t have to come on set to adjust. Once again Nathan Crowley made our lives easier.”

“We always thought of the moon sequence as a little bit of a waking dream. It needed to have a certain surreal, ghostly quality, which was certainly something that we saw from the archival footage on the moon. We really wanted to make sure to capture a feeling unlike the

rest of the film.”

First Man builds to its crescendo with the moon landing and the moments Armstrong and Aldrin spend exploring the powdery surface. To represent the lunar landing site, known as Tranquility Base, Nathan Crowley designed a massive outdoor set in an Atlanta quarry. “As luck would have it, Georgia has a lot of gray gravel quarries full of fine powder, and the one we found was kind enough to get out their big digging machines to help us sculpt the moon,” he reports. “We built a full-size [Lunar Excursion Module] on our moon location, and our greens department sculpted the landscape directly around the LEM to exactly match the real Tranquility Base landing spot. The reference was all there in the original NASA lunar maps.”

Chazelle adds, “We always thought of the moon sequence as a little bit of a waking dream. It needed to have a certain surreal, ghostly quality, which was certainly something that we saw from the archival footage on the moon. We really wanted to make sure to capture a feeling unlike the rest of the film.”

Toward that end, and to emphasize Armstrong’s first step onto the moon, Sandgren switched formats from the Super 16mm that had been used in the spacecraft interior to 15-perf 65mm Imax, shooting Kodak 5219; the Imax MSM camera was paired with rehoused medium-format Hasselblad/Zeiss prime lenses. The large format is introduced with a shot that travels from inside the LEM, through the open hatch, and out to the surface of the moon. The dramatic change in formats, Sandgren notes, is most pronounced when viewed in a 1.43:1 Imax theater.

“I wanted to light that whole Tranquility Base set with a single source lamp, but it was a little challenging to find something bright enough for the enormous set Nathan Crowley was building in the quarry,” Sandgren recounts. “We tested two 100K SoftSuns stacked together, mounted 500’ away, and at the correct azimuth, 16 degrees up on the crane. It worked pretty well exposure-wise, but I felt like it would be better with a single source.

“I was talking with [ASC associate member] David Pringle [chairman and CTO of Luminys, the SoftSuns’ manufacturer] during the test and asked how they actually make the bulbs,” the cinematographer continues. “He said, ‘We hand-blow the globes in our factory in China.’ So I said, ‘What would it take to make us a 200K double-strong lamp?’ David thought about it and then came back the next day and said, ‘Okay, I’m going to build you two 200K SoftSuns and have them ready for you to try on the shoot.’

“Our first night of production on the moon set, the 200K SoftSun was mounted 150’ up on a mobile crane, and it gave us a 5.6 stop — with 500T stock rated at 400 ASA — across the entire 500’-wide set and more,” Sandgren says. “The light was very even and super-nice.”

“There were also many other people who put so much extra effort into thinking outside

of the box.”

FotoKem processed all of the production’s negative. EFilm then scanned the 16mm and 35mm footage at 3K for dailies and at 6K for the final digital grade — in both instances, it was then down-converted to 2K — and Imax scanned the processed 65mm film at 8K. For the grading work, Sandgren worked with supervising colorist Natasha Leonnet and dailies colorist Matt Wallace to customize a Kodak-print-emulation LUT.

“We have Matt’s dailies as the starting point for the DI, and I don’t like to go too far away from them,” the cinematographer explains. “I want to be very true to what the negative gives us by having the Kodak-print LUT and not doing too much to it in post — it’s more about balancing and skin tones and fixing any issues. I also like to do the push- and pull-processing during production and not leave the creation of those looks until the DI, because it really affects the contrast and changes how you light the scene.”

“Linus spent the first few days [of the final grade at EFilm] doing an initial pass with Natasha,” Chazelle adds. “Then she worked for a week on her own, and then I came in for a week and got it to a place I was happy with — and then we brought Linus back in again to see what he thought. It was a lot of back and forth, which is the way I like to work.

“This movie was a true collaboration between myself, Linus, Ryan, [screenwriter] Josh Singer and everyone else on the team,” the director continues, speaking with AC on the final day of postproduction before the film’s premiere at the Venice Film Festival. “It wouldn’t have been possible without Linus being both amazingly adaptable and steadfastly committed to a vision. He’s never one to take the familiar approach; instead, he always finds a way to inject his work with emotion, authenticity and specificity. We all wanted First Manto feel like a documentary that was discovered in the process [of making it]. It didn’t turn out exactly the way any of us had intended, and I think that’s for the best.”

Sandgren is similarly satisfied with the finished film and the creative collaboration. “I loved the way Damien approached the making of this film,” the cinematographer notes. “It was as if he were a completely different director from La La Land. He did a lot of detailed research for historical accuracy, and then set out to tell this story in as real and true a fashion as possible.

“There were also many other people who put so much extra effort into thinking outside of the box,” he continues, “like Paul Lambert, who was up for creating visual effects [for the LED screens] in preproduction instead of postproduction. That helped so much to accommodate the lighting and create the world for the actors. And people like David Pringle, who made us the strongest lamp in the world just because we needed it. That doesn’t always happen. I’m really happy that so many people went the extra mile for this project.”

Following their safe return to Earth, the Apollo 11 astronauts — Armstrong, Collins and Aldrin — all accepted honorary membership in the ASC, for their expert camerawork that allowed the people of the world to share their historic lunar experience. You'll learn more about the cinematography of documenting Apollo 11 here.

Sandgren has earned an ASC Award nomination for his outstanding camerawork.