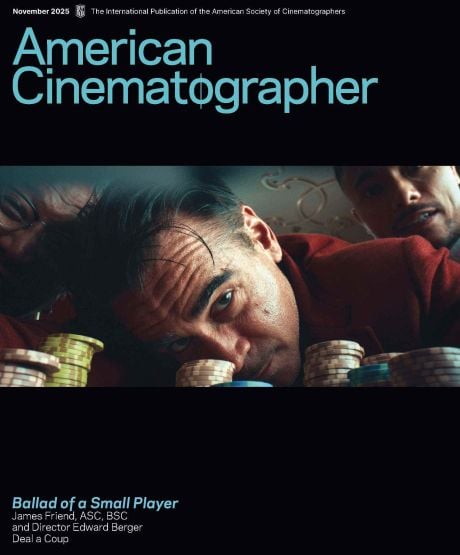

Narc: Arresting Images

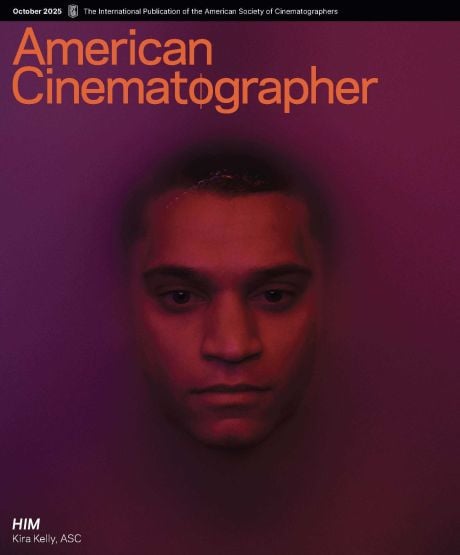

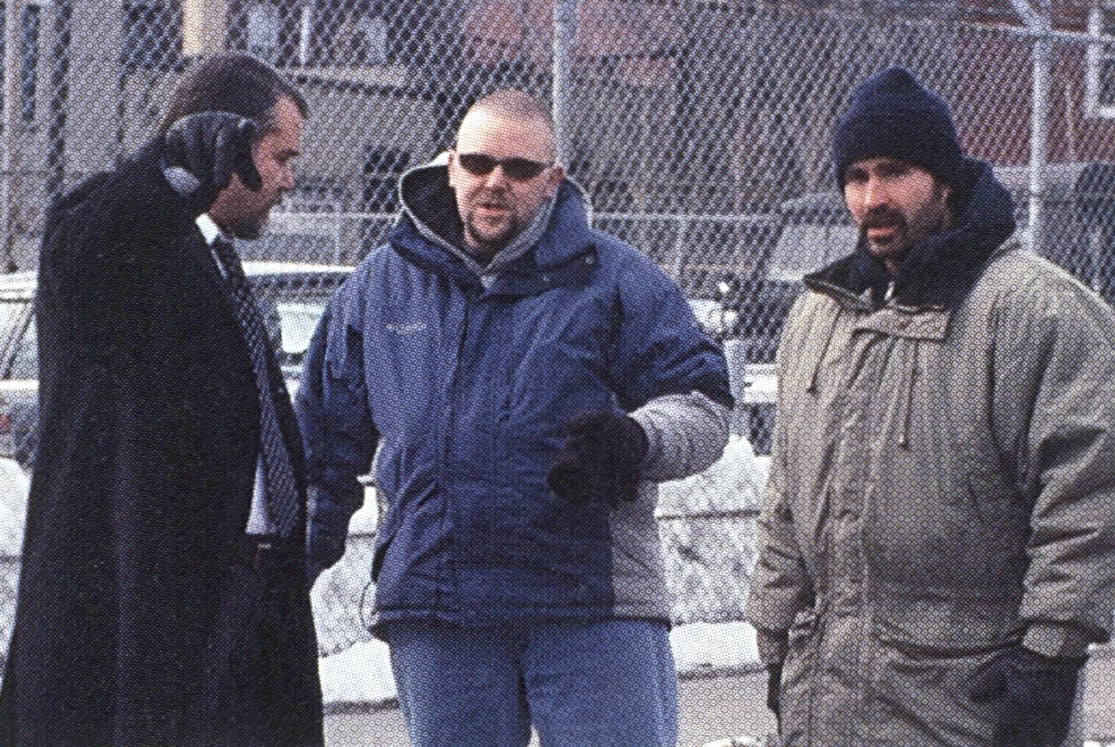

Director of Photography Alex Nepomniaschy, ASC and director Joe Carnahan break the rules on this brutal crime drama.

This article was originally published in AC Dec. 2002.

Unit photography by Michael Courtney

The grim, solitary world of undercover police work has been a Hollywood mainstay for years, as depicted in such films as The French Connection, Serpico, Deep Cover and Donnie Brasco — not to mention the numerous TV shows that have mined similar territory over the decades. The conflicted character of an officer trying to do right while working within a vile world of wrongs still fascinates audiences, though it’s not entirely clear how much viewers truly want to know about the ugly realities of this dangerous and lonely profession.

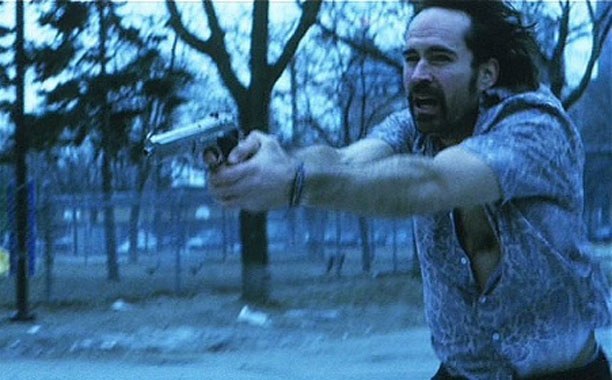

Written and directed by Joe Carnahan, Narc offers an unflinching depiction of an undercover investigation gone wrong — one in which the action becomes motivated by anger, frustration and guilt rather than justice, resulting in a complex drama with few heroes. The film, which premiered at the 2002 Sundance Film Festival, tells the story of troubled undercover narcotics officer Nick Tellis (Jason Patric), who is given a chance to redeem himself by investigating the murder of another deep-cover cop. Tellis is teamed with the dead cop’s former partner, Henry Oak (Ray Liotta), a volatile lawman seeking to avenge his friend’s death. As they work the case, a twisted realm of secrets and betrayal threatens to destroy them both.

Carnahan’s previous feature, Blood, Guts, Bullets and Octane, was shot on 16mm for a mere $7,300 (see AC March ’99), and it revealed a rookie filmmaker whose facility for verbal gymnastics generally overwhelmed any sense of visuals. For Narc, Carnahan knew he had to strike a careful balance between the film’s content and its cinematic presentation, but he also wanted to retain the run-and-gun shooting style he’d developed on Blood, Guts. He felt that a frantic production pace would fit his tight budget and a frenetic camera would suit his story.

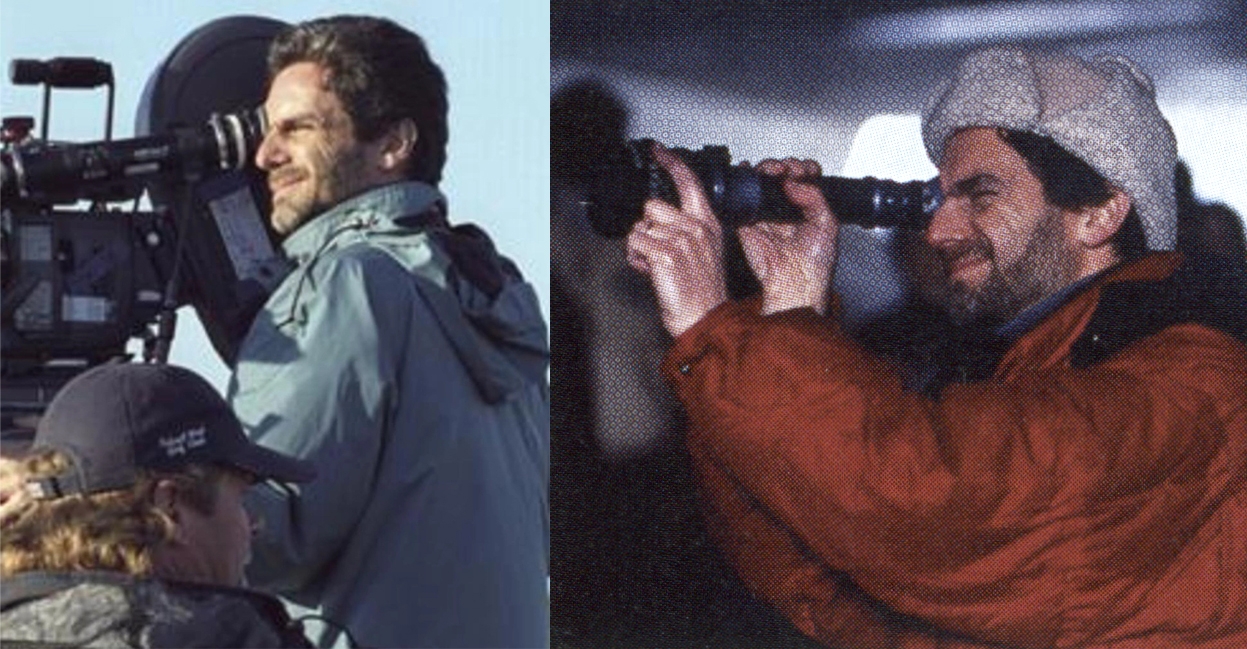

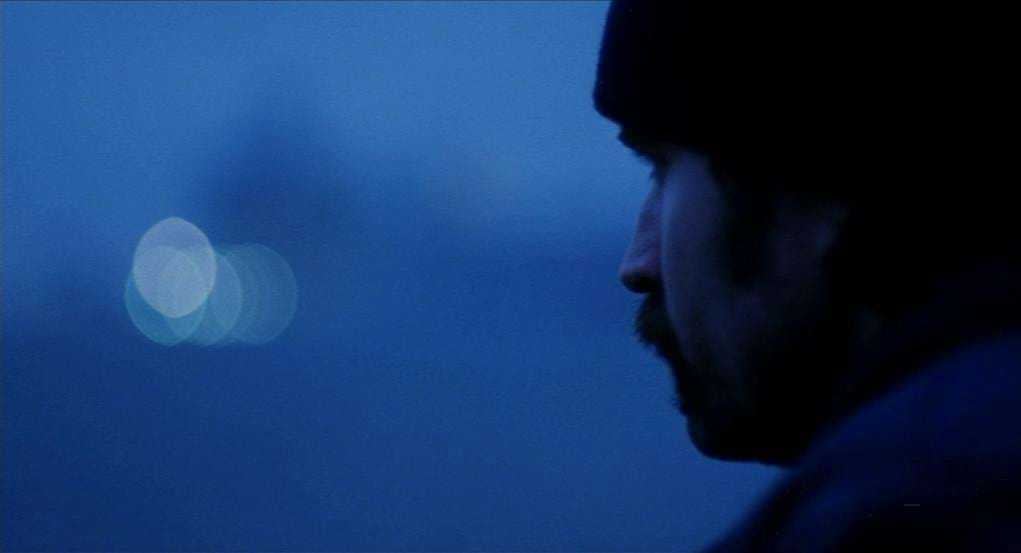

“It’s no revelation that film is a visual medium, but some directors often rely on dialogue to the point where their film is just a series of talking heads,” Carnahan says, admitting his own guilt in this area. “But I had to tell this story visually, especially in terms of Ray Liotta’s character. We had to really crawl inside his head and visually depict what was going on in there as he gradually reveals certain aspects of the story. It was not only about photographing him, but also about carefully choosing the backgrounds he was up against, the lighting and the compositions. There’s one scene in which he talks about his wife, telling Jason’s character the story of her death as they sit in a parked car. It was important to convey his sense of loss and disruption, so we shot him through the windshield with a lot of obstructive reflections crisscrossing his face, while we shot Jason clean. Little things like that add up and become a tapestry, helping you to tell a better story.

“The first thing that entered my mind when reading Joe’s script was using a handheld camera. The story needed that sense of immediacy and energy, especially in the opening scenes.”

“The school I come from is more of a vérité, handheld approach; I want to immerse the viewer in as much reality as we can muster,” Carnahan adds. “We were forced into that style for logistical and budgetary reasons on Blood, Guts, but it also lent itself rather nicely to Narc. That approach is set up with the opening scene, a long chase that we shot handheld. On Narc, we had an incredible amount of script territory to cover in a short time, just 27 days in Toronto and a single day in Detroit. The opening shot was done in Detroit, which was critical to establishing the flow of the film. Toronto can serve as parts of other cities — it’s passable here and there as New York, San Francisco or Chicago — but if you take too hard a look at it, the illusion just doesn’t hold up. Also, it just doesn’t have the vibe of Detroit, which I believe is the great American city that they gave up on.”

Carnahan’s search for the right cinematographer to shoot the modestly budgeted Narc led him to interview several candidates. The deciding factor, however, was his memory of director Todd Haynes’ 1995 film Safe, which told the tale of a young woman who becomes deathly allergic to her environment. The film was shot by Alex Nepomniaschy, ASC. “I think Safe is one of the most exquisitely shot, directed and acted films of the last quarter-century,” Carnahan maintains. “What attracted me was the way Alex created a sense of wide-angle desolation, which really added to the film’s main character, who was on a very singular, lonely journey. [The mood of Safe] related well to what I wanted to do in Narc, because we had to see the film through the eyes of Jason’s cop — a lonely character — and I felt Alex had a firm grasp on that feeling. On Safe, he was never afraid to go really wide in an almost Kubrickian way. I foresaw using a similar approach on Narc, although our subject matter was certainly different.”

Born in Russia, Nepomniaschy moved to the United States in 1974. After studying at the American Film Institute, he shot music videos for such artists as REO Speedwagon, Stanley Clark, Amy Grant and Smokey Robinson. He broke into features in 1986 as a cinematographer on the comedy The Last Resort, and then began building his credits on TV series and telefilms. He earned an ASC Award nomination in 1989 for the pilot episode of ABC’s Sable. His feature credits include Wanted: Dead or Alive, Mrs. Winterbourne, Life During Wartime (a.k.a. The Alarmist), Never Been Kissed and A Time for Dancing. In 1995, his work on Safe earned a Best Cinematography award from the Boston Society of Film Critics.

Asked about the kind of departure Narc offered from his previous assignments, Nepomniaschy chuckles, noting, “That was something I really enjoyed, especially as it was an opportunity to do a lot of experimentation. I also thought the screenplay was wonderful. The first thing that entered my mind when reading Joe’s script was using a handheld camera. The story needed that sense of immediacy and energy, especially in the opening scenes, and Joe responded to that idea. Second, we needed a sense of the coldness, a bluish color to reflect the winter days.”

“After seeing Wanted: Dead or Alive, I had no doubt that Alex could shoot action,” Carnahan attests. “He’s an old-school European who fled Russia at 17, so I also knew that he was a guy who really understood the idea of being cold!”

During their short prep, Carnahan and Nepomniaschy discussed shooting Narc in the anamorphic 2.40:1 format, but for budgetary reasons, they decided to shoot the picture in standard 1.85:1. The cameraman relied mostly on a set of Zeiss Superspeed primes — and an occasional zoom — which were mounted on his A-unit Moviecam and B-unit Arriflex BL. William F. White supplied the show’s camera and lighting gear.

“When you know you have [a scene] covered, move on. If you’re dawdling or dragging your feet, it’s either because you haven't planned properly or because you’re afraid.”

While breaking down the script and determining their approach, the pair took a close look at The Insider, shot by Dante Spinotti, ASC, AIC. “We both admired the look of the film, especially the use of handheld camera,” Nepomniaschy says. “We also [noted] the use of color to reflect the moods of the scenes, which suggested how far we might go on our film.”

Carnahan and Nepomniaschy’s discussions about Narc's lighting conjured images of classic crime films. “I like natural and available light, the type of lighting you’d see in Dog Day Afternoon and Serpico,” says Carnahan. “So many movies these days are so overlit that it’s almost a revelation to watch those films today. You almost say, ‘My God, how did they light that?!’ But that look was also [appropriate for] the overall naturalistic style of those films — the dialogue doesn’t sound scripted, the locations look real, the form offers more freedom, and those were all things we were trying to achieve. So Alex and I agreed on a similar approach: letting the exteriors blow out, letting everything go blue — it was all inspired by films I first saw 25 years ago.

“There’s a lot of lighting in [Narc], but Alex used it in a way that augmented whatever was present in our locations, whatever source was coming in through a doorway or a window. There wasn’t a lot of painting with or finessing the light. One particular sequence, in which Tellis and Oak drive to a crime scene, was done almost entirely with natural light.”

“That scene was unusual in that we used [Kodak Vision 800T] 5289,” Nepomniaschy details. “It was available light with the exception of a little fluorescent fixture that added a bit of fill from the front. I didn’t mind a bit of grain in this film, so 89 was perfectly acceptable. Using that stock was really the only way to get the shot the way we’d planned it.

“We actually relied a lot on Kino Flos throughout the film, but we generally didn’t use a lot of fill, and we deliberately didn’t try to balance our lighting,” he continues. “If an actor was close to a source, we’d just let the highlights overexpose. And as he moved away from that source, the light dropped off very quickly.”

“Adding to that documentary feel, we didn’t worry about setups we'd planned," Carnahan recounts. "That was good, because the scene became just about its base parts: running, shooting, panicking, and finally having to make a horrible decision on the fly. I realize today that if we'd done all of those other setups, I probably would have cut the hell out of the scene. As it stands, there are only about 10 cuts in the entire sequence, which isn't a lot. You'd think that a chase should be cut, cut, cut, but not this time, and it works. It's lean and mean.

"In the editing room, you have to be a keen assassin — when something isn't working, you have to kill it, no matter how much you love it,” Carnahan continues. "It's the same with shooting. When you know you have [a scene] covered, move on. If you're dawdling or dragging your feet, it's either because you haven't planned properly or because you're afraid."

Of course, the execution of this "simple" scene was more difficult than it looks. Given the speed and length of the chase, Nepomniaschy knew that the lightest camera possible would give Willis his best shot at keeping pace. And after some discussion, the filmmakers worked with William F. White to modify an Arri 2C, fitting it with a knapsack-style battery pack, a special video tap and an onboard LCD monitor that allowed Willis to "fly" the camera after actor Patric. The tap transmitted a signal to a remote monitor for the cinematographer and director to observe. "It was the most appropriate tool for the job;' Nepomniaschy says. "Chasing after Jason, it would have been impossible for Mark to keep his eye at the viewfinder."

While this may sound like a poor man's Steadicam rig, Nepomniaschy and Carnahan made a conscious decision not to use a stabilizing mechanism: "We wanted that documentary shakiness, as opposed to fluid movement;' the cinematographer says, adding with a laugh, "The 2C was our 'special' camera. Actually, it's just so old, but that LCD screen made it seem like it was really special."

Noting that 85 to 90 percent of Narc was shot handheld, Willis explains that the difference between true handheld camerawork and the Steadicam marks a crucial aesthetic choice: "You get a bit of a floating sensation with the Steadicam. Really good Steadicam work should look like the camera is on a dolly. But the Steadicam can't do a whip pan like you can do if you're working handheld — the frame always ends up floating a bit — and that harder edge, that snap, was important to the action in Narc. Also, in tight locations like the ones we were working in, going handheld gives you more options.

"We ultimately shot part of the opening chase scene with the Steadicam, most of it running handheld with the Arri 2C, and then shot some handheld from a golf cart with the Moviecam," Willis continues. "We used a 20mm lens to give ourselves a greater chance of keeping the subject in frame. We also had a FTZSAC remote follow focus on the camera at all times, which allowed our focus puller to stay out of the way while he was doing his thing."

Willis adds that he rehearsed his handheld work throughout the shoot with the aid of the lightweight Kish UltiMate director's finder, which features a color video tap and transmitter that allowed Carnahan and Nepomniaschy to study Willis' moves and make suggestions, basically locking in the camerawork before the operator had to hoist his Moviecam. "The Kish was a real back-saver,” he attests. "While talking with Alex early on about how much handheld work would be in the film, I told him we could really use one of these finders. It was very useful."

Complicating the crew's efforts to capture the chase sequence was the limited sunlight available in Toronto on that February afternoon. "It was getting dark by 4:30,” Carnahan says, "and we still had a number of shots to get. We were limited to the number of takes we had, and we had to live with what we got. Fortunately, it turned out great."

To accentuate the feeling that the chase had happened in the past, Nepomniaschy utilized Deluxe Toronto's proprietary bleach-bypass process on the original camera negative. The process had to be done at this stage, as it was used only on the first few minutes of the first reel. Also, the cinematographer preferred the effect when it was applied to the O-neg as opposed to an interneg.

Getting coverage again became an issue for a confrontation between Tellis and Capt. Cheevers (Chi McBride), who is forcefully trying to convince the officer to look into the Calvess case. Fading daylight was not the issue this time, however: "That scene was one of the few we shot on stage,” Carnahan recalls. "We built a police station set, and the action takes place on a central staircase. After watching the dailies, one of the first things I heard [from the producers] was, 'Where's your coverage? You just shot that wide, and that was it!' But I had total confidence in what Alex and I had done because I knew the scene would be intercut with footage of Jason relating the story to his wife — this scene is his story of what happened, so why would I want to go in for tighter coverage? Anything other than a subjective wide shot would suggest that there is a relationship between the two men. In fact, they've just met and have no connection at all, so staying wide made sense for several reasons. Instead, we used the space and symmetry around them to exaggerate the physical and psychological distance between them, and I think it worked really well."

Because Narc is an intricately edited film — replete with split-screen effects, multiple flashbacks and fragmented memories as Tellis and Oak get closer to the truth — Nepomniaschy's stark, naturalistic lighting also serves to ground the story in realism, negating the danger of the film veering off into an "MTV-like" aesthetic. "There's a low-key, impressionistic look to some of the film, but the photography in Narc didn't need the kind of visual flourish that you see in a lot of films today," Carnahan maintains. "Because of our editing approach, we knew it was important to avoid over-stylizing the lighting and the look. We were going to be adding a layer of stylization with the editing — abstracting the images — so we wanted to start with clean material that would be easy to identify quickly."

One key sequence depicts the murder of deep-cover officer Michael Calvess (Alan Van Sprang), which is repeated throughout the film with increasing clarity as Tellis and Oak piece together their clues. Staged in a claustrophobic tunnel on a rainy, bone-chilling day, the killing is seen at first from a distance, with Calvess and his two attackers appearing as diffused silhouettes, like a fragment of some half-forgotten dream.

“One of the first things [Joe] told me was that he wanted to take chances and try new ideas, and he never backed away from that. That's the best kind of support you can get."

''At this point in the film, Tellis only knows that Calvess was beaten and killed in a tunnel,” Carnahan says. "With that in mind, Alex and I decided to abstract everything about the event except the rain — Tellis knows what rain looks like — so the only part of the image that's in focus are the raindrops, which appear in the foreground as the murder takes place, blurry and out of focus, deep in the background."

After taking the Calvess case, Tellis studies crime-scene photos detailing the victim's appearance and grotesque wounds, adding more detail to his mental image.

Later, as witnesses to the murder recount their stories, the action is seen (in classic Rashomon fashion) from their points of view and is limited to what they think they saw. To help suggest the feeling of a fading memory, Nepomniaschy suggested shooting the Calvess murder sequences on Kodak Ektachrome 100D 5285 color reversal film and cross-processing the footage in negative chemistry to create high-contrast, super-saturated images that would add a level of abstraction. On a subconscious level, even the most fleeting images imprinted with this unique look would instantly register with the audience as being a part of the Calvess puzzle.

Though Nepomniaschy hadn't used this technique before, tests during prep gave him confidence. Throughout the shoot, he had to rely on video dailies, but he did request and receive film dailies for his crossprocessed work, which was done at Technicolor in New York. "You're riding on the edge of the film when you're doing this,” he says. "Crossprocessing really distorts the colors, so you have to see what you're getting from film on film — otherwise, you're just guessing. We wanted to see how far we were really going, so it was important to screen that footage.” He also wanted to see how much contrast would be added by Kodak's Vision print stock.

Finally, as the truth about Calvess' murder is revealed, the flashback takes on an entirely new look — Nepomniaschy shot this version of the sequence on 5279 to match the look of the rest of the film. "All of the previous versions were affected by Nick Tellis' imagination,” the cinematographer explains. "They were based on the information he gets, so we wanted to emphasize in a subtle way that this is what actually happened.

"Joe brought a lot to the table, including an amazing passion for this story,” concludes Nepomniaschy, who is thrilled by the support Paramount is putting behind the independently produced picture. "But most of all, he brought an incredible amount of support for his cinematographer. One of the first things he told me was that he wanted to take chances and try new ideas, and he never backed away from that. That's the best kind of support you can get."

TECHNICAL SPECS

1.85:1

Moviecam and Arriflex cameras

Zeiss lenses

Kodek Vision 500T 5279, Vision BOOT $289, Ektachrome 100D 5285

Bleach Bypass (select scenes) by Deluxe Toronto

Cross-Processing by Technicolor New York

Printed on Kodak Vision 2383

Access the every issue of AC and every story from more than the last 100 years with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.