Starship Maneuvers for Starship Troopers

Sony Imageworks and its allies develop and decimate an interstellar armada.

This article was originally published in AC November 1997. Some images are additional or alternate.

Visual effects supervisor Scott Anderson has traversed a long and winding road from the sweet barnyard shenanigans of Babe to intergalactic battles of Starship Troopers. After earning an Oscar for Best Visual Effects on Babe with Rhythm & Hues, Anderson began a three-year-long association with Sony Pictures Imageworks, contributing CG water and digital shark elements to James and the Giant Peach and later heading up Die Hard: With A Vengeance. Anderson then signed onto the ill-fated Roman Polanski project The Double. When that film floundered, Anderson enlisted for duty on Troopers while Imageworks chief Ken Ralston made Contact with director Robert Zemeckis.

Remarkably, Anderson has never before supervised effects for a science-fiction film. But in his role as Troopers' senior visual effects supervisor — working alongside visual effects supervisor Dan Radford — Anderson received the opportunity to experiment with concepts he'd always hoped to see in outer space. Director Paul Verhoeven (RoboCop, Total Recall) fully supported Anderson's ideas, and even added a few of his own to the mix: "When I first started talking to Paul, he was aiming to create this epic war film in space as well as on the ground. Dan Radford did a lot of work before I came on, but I worked very closely with Paul, designing some major sequences which really hadn't been tackled yet.

The majority of our shots take place over various alien worlds as the troopers' carrier ships come into orbit, and during the subsequent space battles. This was a massive project, and we had about 270 people working for Imageworks during the course of the production — we're doing about 120 shots."

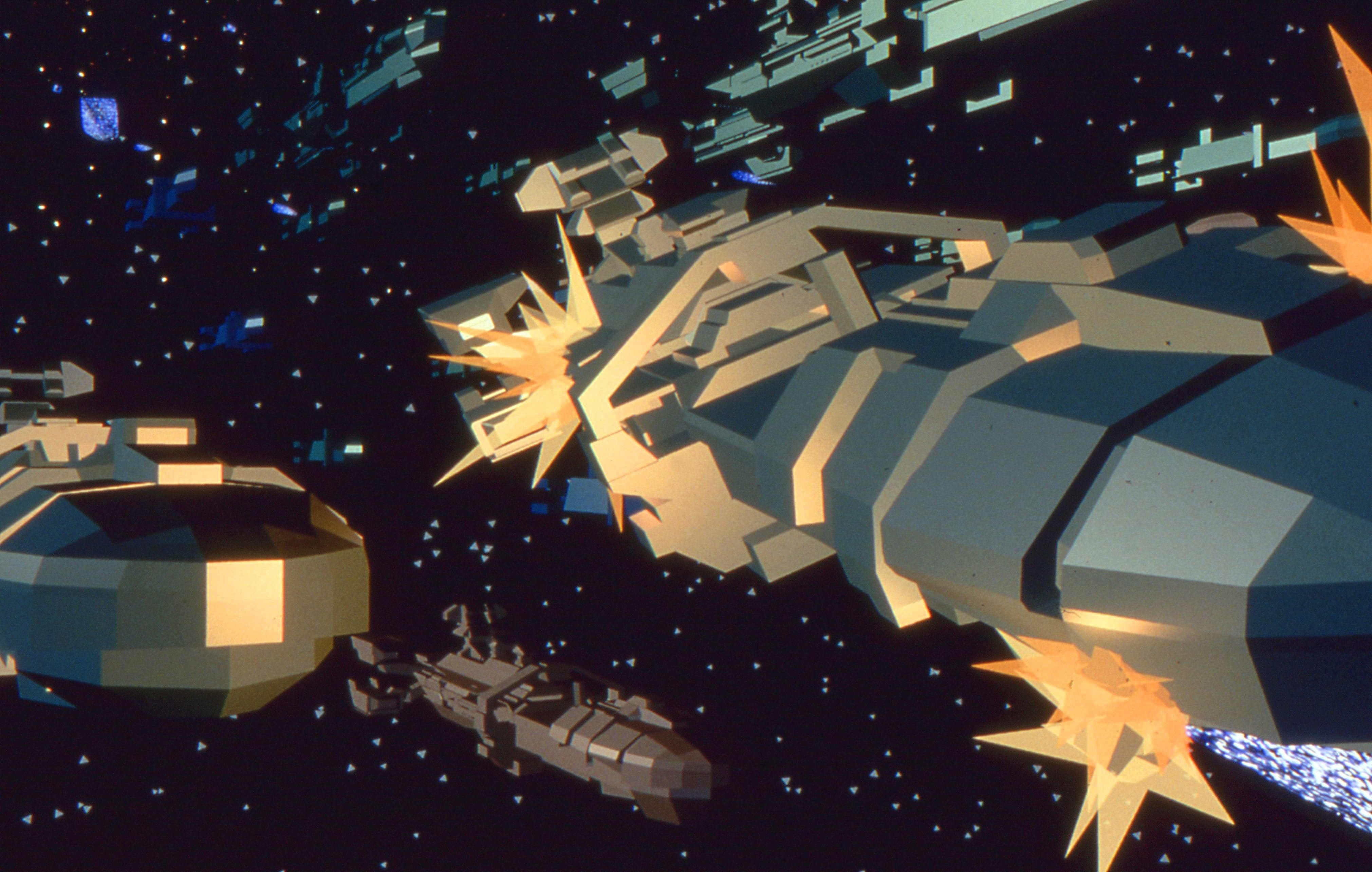

Troopers' scale became so immense that ILM and Boss Film were solicited for several sequences while the giant extraterrestrial insects were supervised entirely by animation maestro Phil Tippett. This left Anderson and his Imageworks troupe to concentrate on the bulk of the starbound scenes, including the film's two climactic battles as witnessed by the crew of the starship Rodger Young. The first skirmish is the terran troopers' blitzkrieg of the planet Klendathu. "The beginning of the sequence is almost idyllic," Anderson says. "We see the troopers getting into their drop ships, and getting instructions from their commanders. Then the drop ships are lifted from the interior of the spacetanker into drop position on the exterior. As the troops leave the fleet, there's a 180-degree view through twin suns of the drop ships going down to the planet, in which you get this big beauty shot of Klendathu. The ships begin bombarding the planet and the bugs start attacking the fleet, firing these plasma bursts at them from the surface. The tension slowly builds through the climax of the sequence, where two huge spacetankers, the Marshall and the Yamamoto, collide."

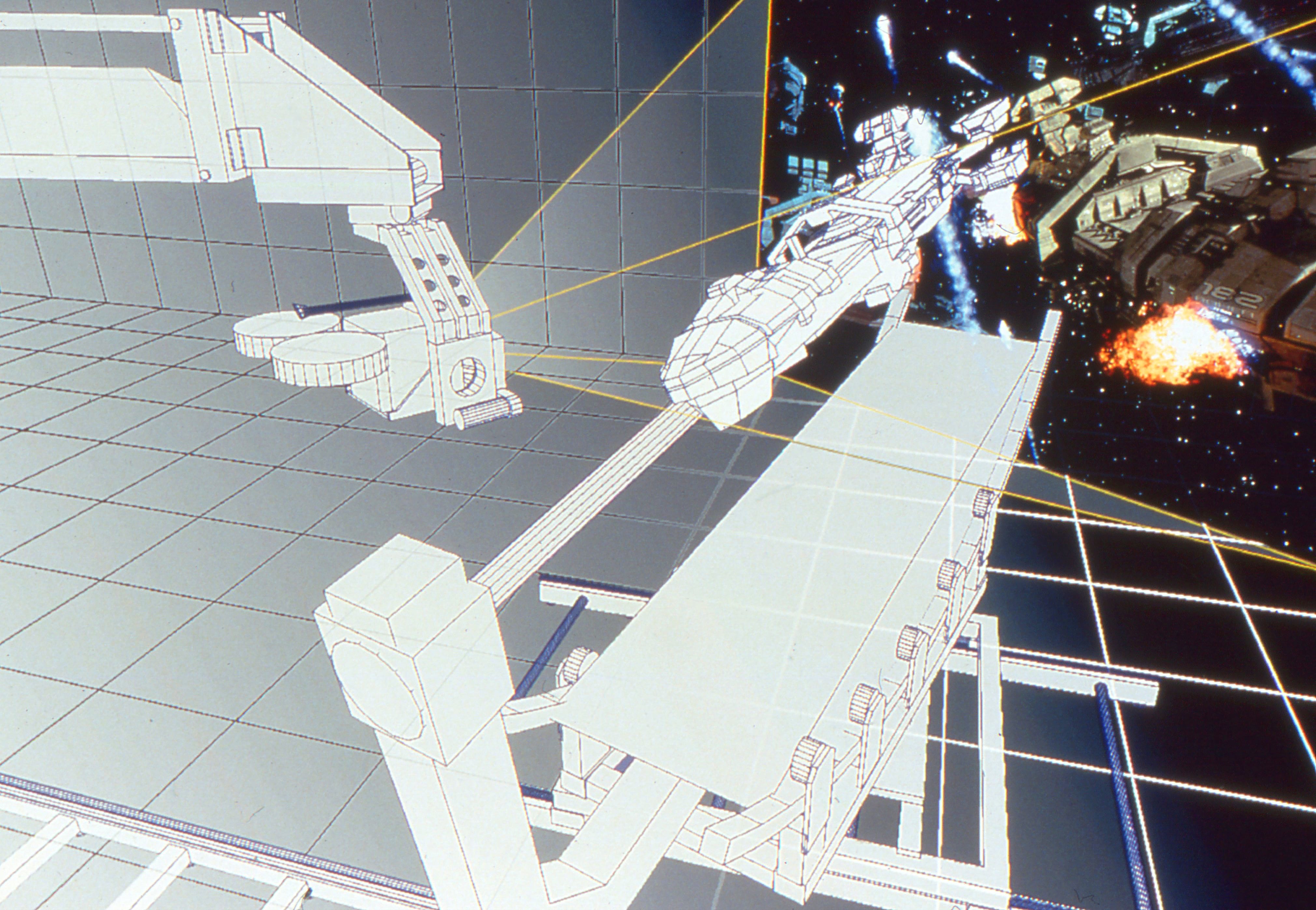

Under Anderson and Radford's supervision, Pixel Liberation Front, which has offices in New York and Venice, California, pre-visualized sections of these battle sequences as digital animatics, using a hybrid system of Silicon Graphics and Windows NT workstations running Softimage 3-D software. According to PLF supervisor Colin Green, "Pre-vis made it easier to choreograph and track the elements. There were so many layers and so much movement that without pre-vis, it would have been much more difficult to shoot every piece correctly."

PLF's pre-vis work involved the creation of a virtual set representing the placement and action of the motion-control rigs, cameras, lighting and other equipment. The animatics also consisted of preliminary blocking for CGI elements, including the bug plasma and many spacecraft.

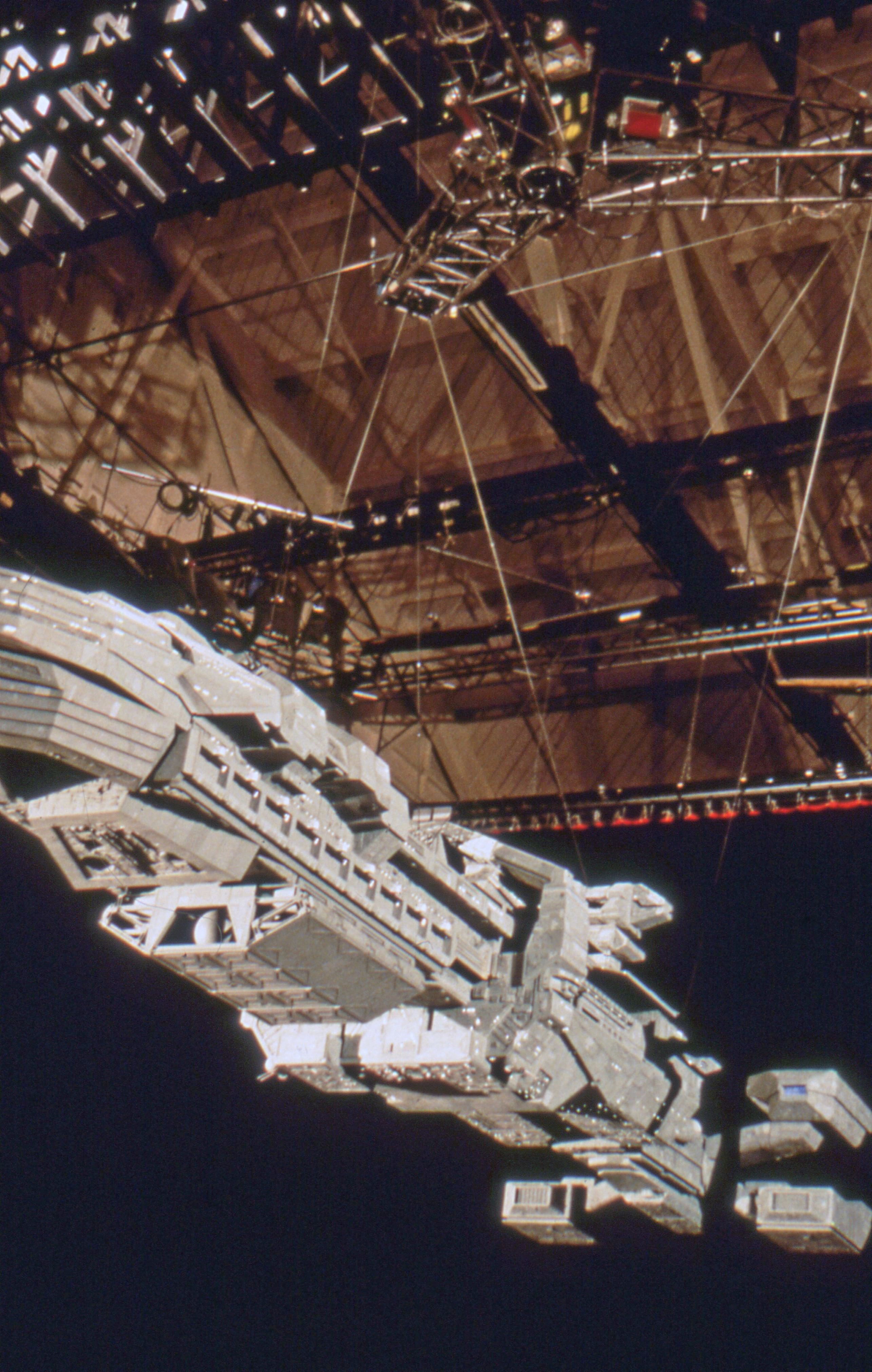

Imageworks' model division, Thunderstone, had their hands full constructing Earth's starfleet, including drop ships, reconnaissance craft and attack fighters. "We built all of the primary models of all the different classes of ships, and some maquettes," Anderson recalls. "In the fleet shots, we've littered space with drop ships — the smaller carrier ships — as well as cargo ships shuttling between the major ships, and what we call 'Tenders.' We also have a few little tugboat-type ships designed for the spacedock portion of the film. We built a large-scale Attack Fighter — the equivalent of a fighter jet — for close-up shots of the assault on Tango Urilla, and we also built pyro versions of the fighters to blow up."

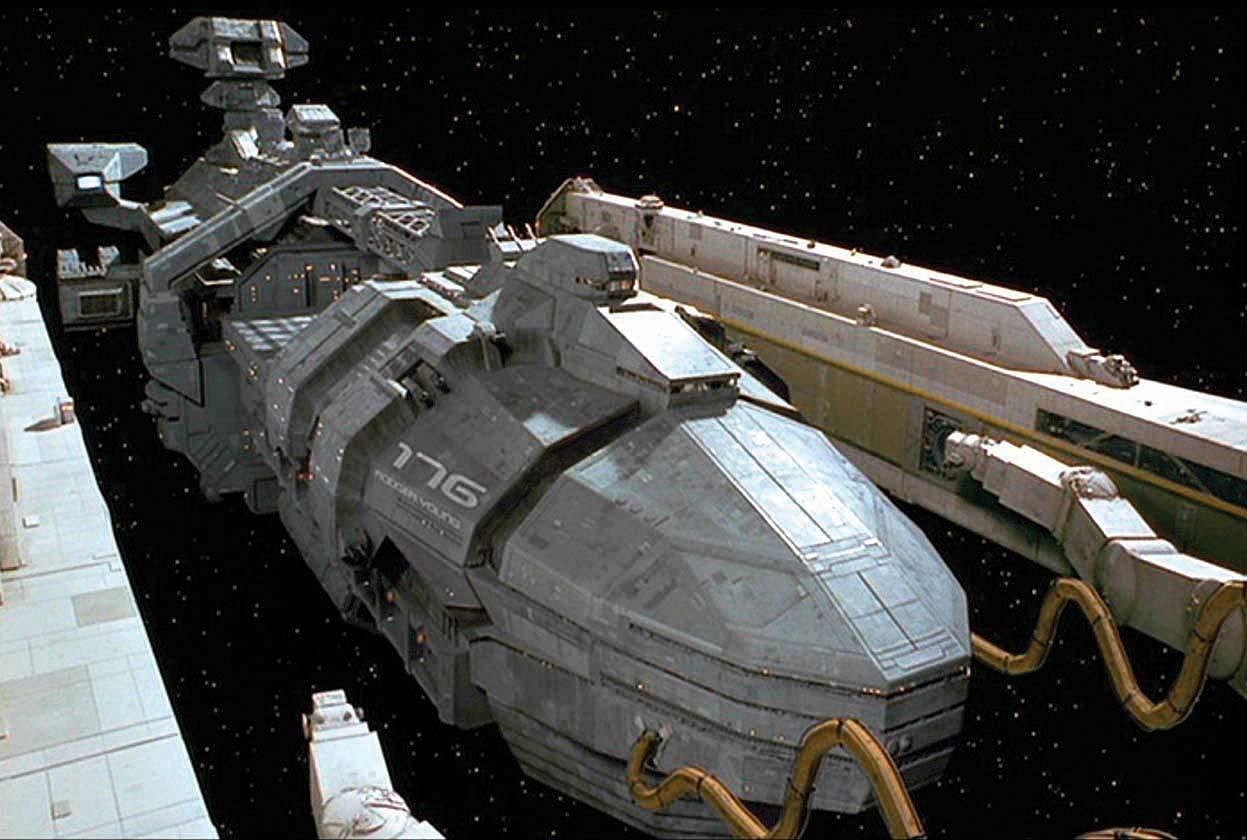

The fleet is comprised mostly of humongous carriers like the Rodger Young, so Imageworks dubbed the massive troop carriers the "Rodger Young class." Says Anderson with a smile, "It's like riding with Car 54: we're always with them, through thick and thin." Thunderstone built several versions of the Rodger Young-class ships, differentiating each with various military-inspired paint jobs: gray-green for the Army, blue-gray for the Navy and tan for the remaining ground troops. The fleet's flagship was coated in Army green. "We built five 9’ Rodger Young-class ships for various functions, and numerous pyro and collision models," Anderson states. "We also had eight small 22" ships to fill out the majority of the fleet, which is hard to do with 9' ships. We only had one 18' Rodger Young, so when Boss Film needed a largerscale ship for a shot involving a bug meteor, we shared some parts with them; ILM built their own 9' Rodger Young and some tiny 3' versions for the Klendathu sequence."

But the colossal scale of Troopers made it virtually impossible for Imageworks to create the epic sweep sought by Verhoeven solely through the use of miniatures. "Each time you see a fleet, it has in the neighborhood of 50 Rodger Young-class ships," Anderson explains. "In the big sweeping shots, all of the background action and all of the detail work was done with intermixed digital and miniature ships. We'll have 15 model ships and then another 100 digital ships in a shot. The larger-scale versions of all of the models were done traditionally, except for the Tenders and the tugs.

"We used a combination of Alias software to model the ships and Wavefront's TAV choreography to animate them. We also used Renderman for rendering, along with Birps, our in-house conversion and lighting tool. We did almost everything on Silicon Graphics workstations. Compositing was primarily done using Wavefront's Composer, but we also composited shots on the Cineon and the Inferno — intercutting all of those shots. There were different trade-offs and options with each package, so we targeted shots to each platform depending on their respective strengths."

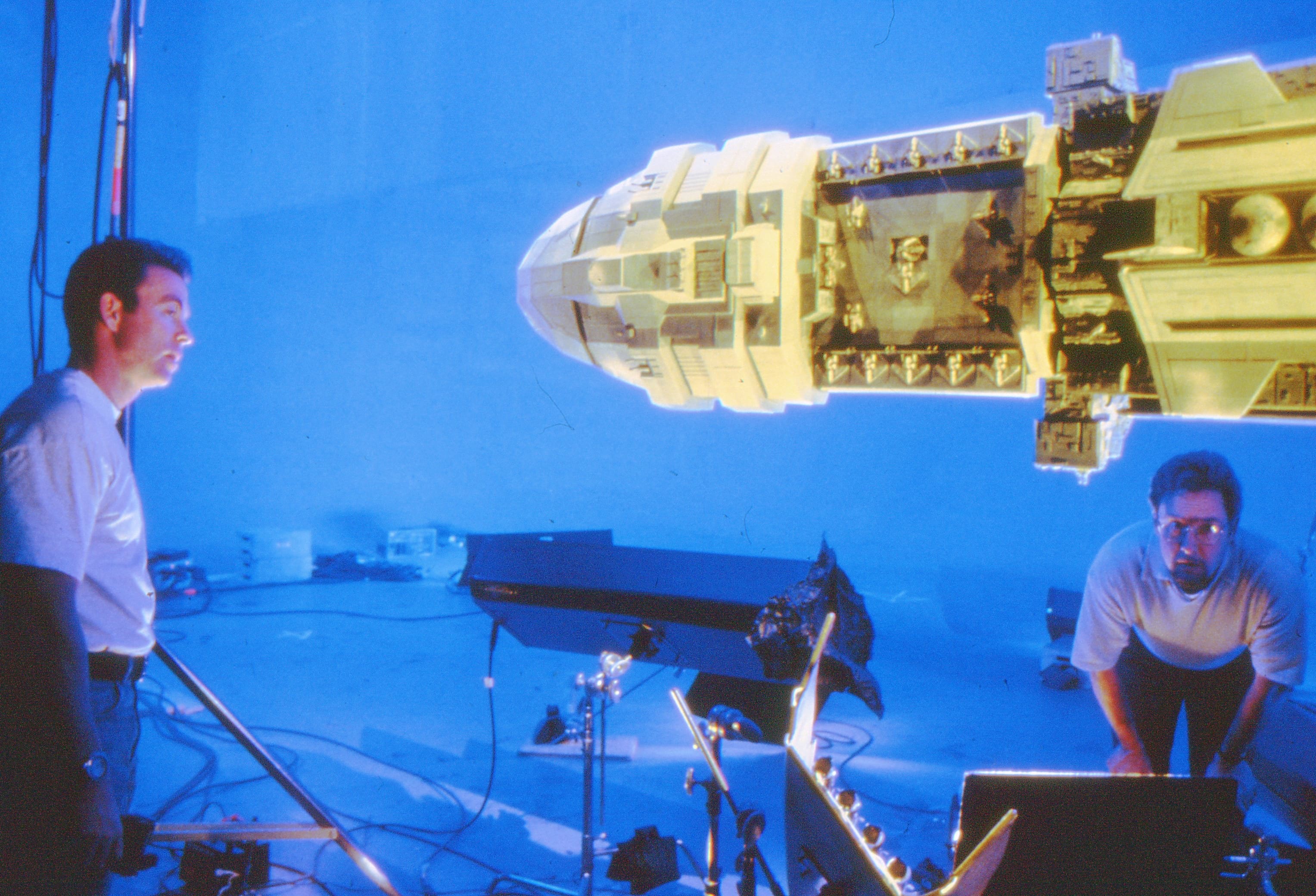

In the Marshall-Yamamoto collision and other sequences, Anderson opted to shoot multiple spaceships simultaneously in the same scene via motion control, rather than taking the traditional tactic of shooting the ships one at a time. "We did multiple ships for the background, some multiples for the mid-ground, and then almost entirely singles for hero shots and hero ships," Anderson explains. "It was a matter of practicality. We had to find ways to make our work more efficient to finish a movie of this scope. Even shooting multiple ships together, we still wound up with approximately 2,000 selected model elements. That number would have been multiplied almost five or six times if we had done individual ships, due to the multiple beauty, lighting and matte passes needed for each ship. We also tried to minimize the number of passes wherever possible. We found some nice light, bright fiber-optic sources for the models, which enabled us to combine fiber-optic passes with beauty passes — for nice savings. While custom lights like the engine sources would require separate passes because they burned so hot, we tried to do as much practically as possible. Our stage crew worked out nice ways of getting scale lights on the models, allowing us to shoot some spill areas in combination with other lighting passes."

Overseeing much of the motion-control work was lead effects cinematographer Pete Kozachik, whom Anderson had worked with on James and the Giant Peach (AC, May 1996). For nine intense months, three Troopers motion-control units, headed by Verhoeven veteran Alex Funke (Total Recall) shot on separate stages at SIR Studios with cinematographers Scott Campbell and Josh Kirshner. "We shot almost everything on Kodak 5248," Anderson says. "We used a real combination of techniques, including UV green, red and blue as hider and helper passes, but our predominant screen methodology was Erland's digital blue. That was partly due to the scanning technology and software we use, but I've always had great luck with blue. While green-screen is usually easier to light, I like the quality of the mattes I get out of a blue-screen."

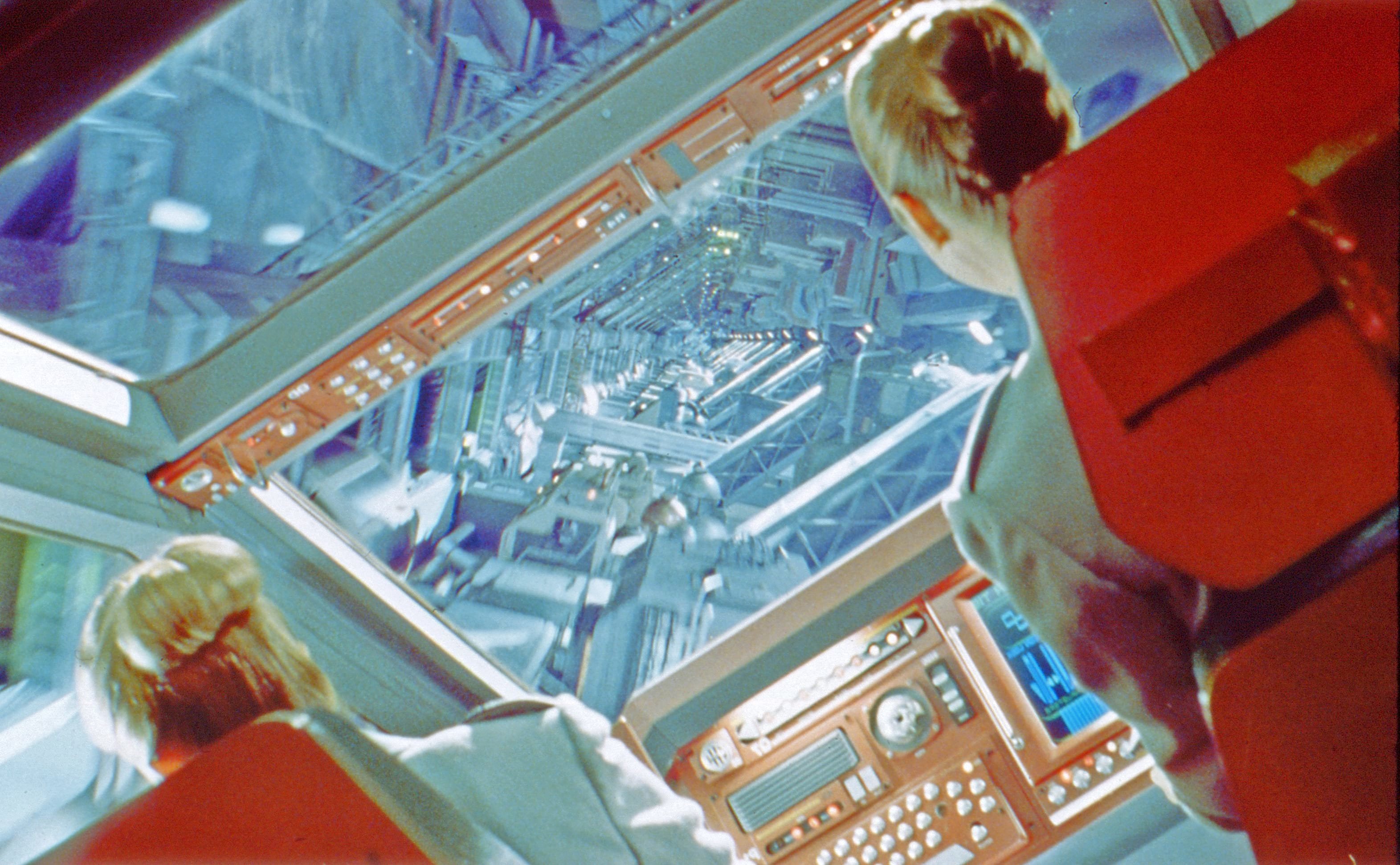

Greenscreen was used for live-action shots of the carrier interiors, replicating the point of view from the bridge peering out at the reaches of space. "Before shooting began, we choreographed each [sequence using digital] pre-visualization," Anderson states. "After Paul and cinematographer Jost Vacano shot the live-action plates, we went through and started engineering the whole sequence of events around what the live foreground action dictated. The POV was constantly changing, like in a car chase, where you go from behind the wheel to over the bumper to the front of the car as it comes at you. For example, we'd have an interior shot of our heroes on the bridge, and their ship diving toward another starship. Then we'd cut to an exterior and watch the ship you were just on coming toward camera and flying past."

Verhoeven had mandated that the outer-space action should seem like "a car chase with supertankers," so according to Anderson, "our shots were designed to be very close to the action with this epic backdrop around us. It's like a car chase on the freeway — cars may blow up and tumble in your path, and the heroes have to avoid those dangerous situations."

An example of this metal-churning mayhem occurs during the culmination of the Marshall Yamamoto collision. The troopers have received mistaken reconnaissance information, and the fleet subsequently falls under heavy attack from the bugs as the Rodger Young, the Marshall and the Yamamoto close in on Klendathu. "As the Rodger Young flies down through this bug plasma field, flanked by the Marshall and Yamamoto, the Marshall has one pair of its engines blown off and tumbles out of control, crashing into the Yamamoto," Anderson reports. "The whole sequence essentially sets up this moment, and you see the concern of the Rodger Young's crew grow as they watch the Marshall and Yamamoto collide right before their eyes. We worked for a very visceral, very physical collision. You're going to actually see crunching and bending metal and fire leaking through the severed and torn pieces of the ship. We shot the ships with motion control, but the actual physical collision was done digitally, so we built digital replacement sections for the ships. We combined various passes on the physical models — clean passes, damage passes, pyro passes, interactive lighting passes — then replicated all of that lighting digitally and did the physical crunch in the computer."

Unlike movie stunt cars, which tend to careen and collapse before exploding, cinematic spaceships often erupt into fireballs immediately on impact. "We're trying to avoid the 'magic doughnut of fire' that spaceships usually punch into when they collide," Anderson insists. "The Marshall-Yamamoto collision happens over a couple of shots, so you actually get to see it. Although this sequence of shots is fairly high contrast and there are some dark areas on the camera side of the ship, we're actually using the pyro to illuminate the action by giving us flashes of detail. There's essentially rim-light from all of the detailed explosions."

As the collision ensues, the Rodger Young ducks under her exploding sister ships and executes its getaway. But during the engagement over Planet P, the Rodger Young finally meets its Waterloo. "As the fleet comes under attack, the Rodger Young banks out of the way of this other starship that's just been hit, and begins to break for clear ground," Anderson relates. "As the bugs start firing, various ships are in all sorts of danger, and the Rodger Young navigates through what looks like a major car crash on [L.A.'s] 405 Freeway. Just as they're about to get clear of this destruction, they get hit by bug plasma [created with a combination of Dynamation, the Wavefront particle system program, and Birps.] It's a classic naval disaster — the Rodger Young is partially ripped apart in the middle, and begins to crack and separate; it has a slow, painful death, fighting bit by bit for survival as the crew tries to escape."

Much of the ship's climactic crack-up was actually photographed in-camera via a unique form of stop-motion animation in which the motion-control camera traveled over the miniature, shooting multiple passes one frame at a time. "It was like Go-Motion, where the details are done on a frame-by-frame basis but the overall big moves are done in a motion control system," Anderson says. "We used our 18' model for the separation pass, and actually built detailed sections of the interior decks of the ship. Then Pete Clynel and Paul Jessel stop-motion-animated the decks collapsing, which were timed to the lights Pete Kozachik set up and designed on stage. We'd have a light go off as Pete shot the explosion pass. The ship doesn't just sit there burning gently; the decks actually pop, move and blow out. As the ship separates and continues to be eaten away by the residue of the bug plasma that nailed it, we dressed all sorts of live-action, large-scale pyro elements — from 4" to 100' tall — into various sections of that model, as well as our 9' version. In the end, the Rodger Young actually breaks apart and begins burning in space. For the final explosion, we blew up three sets of pyro models."

Using stop-motion animation during the course of a motion control shot involving spaceship miniatures was a painstaking technique, but the method lent the operatic grandeur which Verhoeven and Anderson desired for the Rodger Young's demise. "It was a crazy idea that lived on to the very end," Anderson admits. "We're hoping it adds a new level of depth to our hero ship's untimely death."

Lead effects cinematographer Pete Kozachik was later invited to join the ASC.

You'll find a complete story on the film’s creature effects here and the film’s cinematography here.