Pest Control on Starship Troopers

Tippett Studio adds a sense of performance to the film’s swarms of killer insects.

This article was originally published in AC November 1997. Some images are additional or alternate.

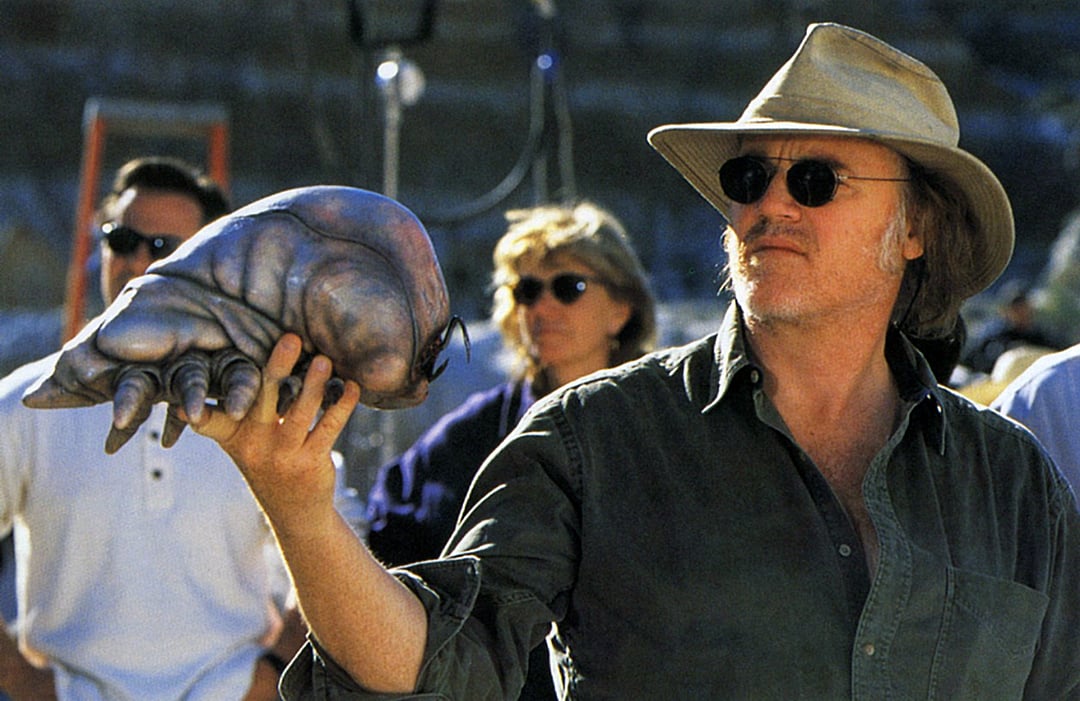

After ace stop-motion animator Phil Tippett netted an Ocscar for his landmark digital effects on Jurassic Park, he feared that his days of conceiving fantastic creatures might be numbered. But Tippett Studio, owned and operated by Tippett; his wife; visual effects producer Jules Roman; and designer Craig Hayes, is still holding fort against the industry's digital tsunami. Having recently completed effects for the family film Three Wishes, the studio used its deft sleight-of-hand to supply armies of marauding insects for Paul Verhoeven's Starship Troopers.

While Tippett designed aliens for the Star Wars trilogy and dragons for Dragonslayer, Willow and Dragonheart, he has rarely been asked to give birth to bugs. Until now, his most notable feats in this realm were the giant scorpion in Honey, I Shrunk the Kids and the quasi-insectlike monster from the much-maligned Howard the Duck. But the effects veteran has never before animated creatures on the vast scale that Troopers required. “There are seven different kinds of bugs, and you basically meet a new bug or two in each of the four key battle sequences," Tippett reveals. "Craig Hayes, who co-supervised the bug visual effects with me, also designed all of the bugs. He's a brilliant graphic designer. We put a great deal of effort into making palpably real fighting bug armies that appeared to have some kind of offensive strategy."

Since Verhoeven stressed that Troopers was first and foremost a war film, Hayes' designs transformed the insects and their armaments into the equivalent of the faceless World War II Axis troops and exaggerated weaponry seen in old Hollywood propaganda films. "The Warriors are the ground-based troops, the Plasma bugs are the heavy artillery, the Hoppers are the air force, and the Tankers are like flame-throwing tanks," Tippett explains. "Craig tried to create some logical consistency within the bug community. For example, the Hoppers are genetically mutated Warrior bugs: they just have legs in different places and differently elongated limbs. In the same way, the Plasma bugs are genetically altered Tankers — they're a lot bigger and look significantly different, but there are a lot of similar design attributes. We wanted to achieve a balance with these alien adversaries. We didn't want you to take it all in or understand what they were the first time you saw them. Instead, we wanted their appearance to manifest itself over the course of 50 shots."

“It’s interesting how the world is divided between people who are either terrified by insects or terrified by reptiles. I never was subject to the fear of reptiles, but insects always gave me the creeps. Making this film was no catharsis.”

Hayes, whose first assignment for Tippett Studio was designing the petulant ED-209 police robot for Verhoeven's RoboCop, found it relatively easy to design killer bugs that met with the Dutch director's approval. "Because of our established relationship with Paul, we worked out some of the overall issues in the first round," Hayes recalls. "We started by breaking the insects down into a bug hierarchy, then into individual groups. We did different drawings of bugs with weird stuff here and there, then fleshed out designs for each particular style. But there was a concerted effort to make them pretty familiar. Troopers is not about this fantastic lifeform: the bugs had to be real and grounded so you wouldn't have any trouble telling the good guys from the bad guys."

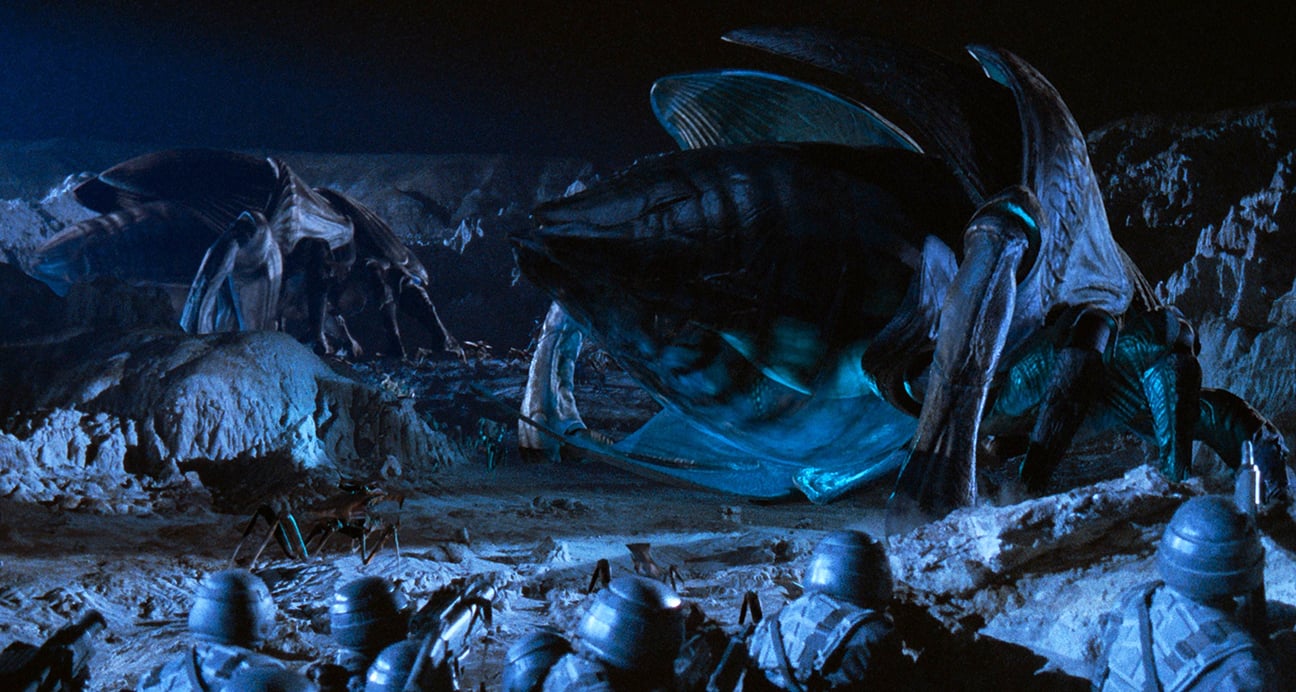

Hayes envisioned that the Plasma bugs would produce explosive goo through an internal catalytic reaction that would then blast tracer-like fire from their backsides. "The Plasma bugs are bulbous and greenish-blue colored with yellow stripes on their thoraxes" Hayes says. "They're 85' tall and based on a cross between stinkbugs and fireflies. Since their butts are transparent, you can see some kind of reaction happening inside. There are only three shots of the Plasma bugs, which are seen in the Klendathu battle sequence: they move into position, take aim like pieces of artillery, and then fire."

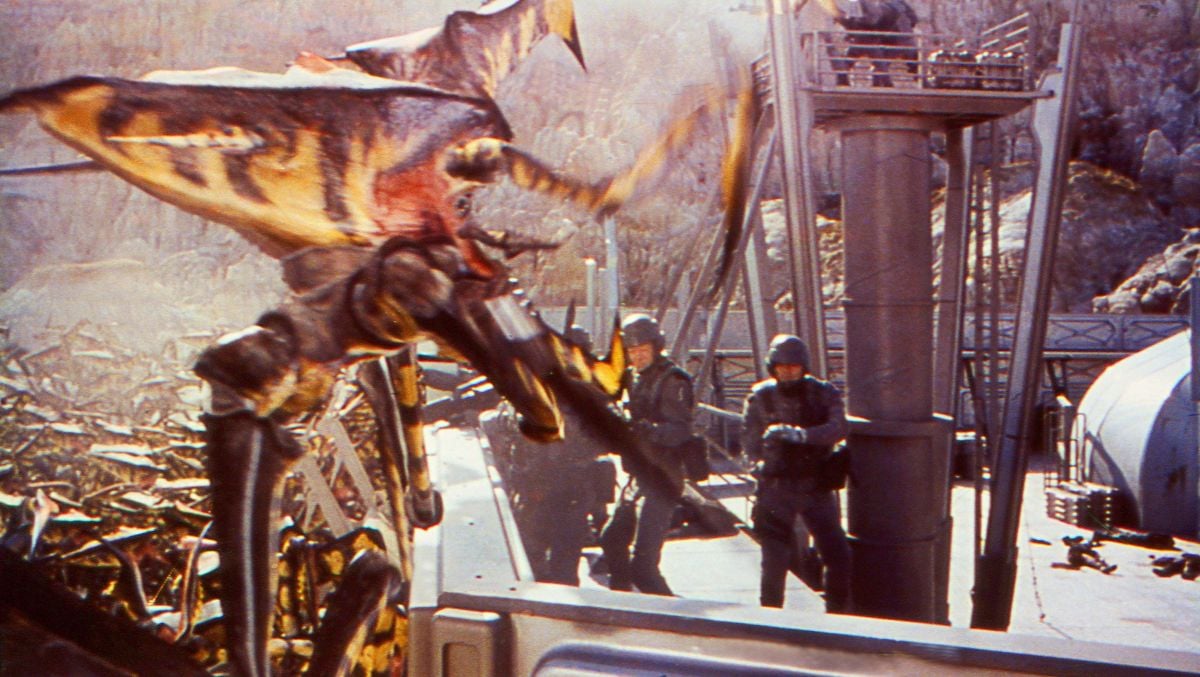

The Tanker bugs, however, are a great deal more mobile. "They're more like half-track tanks," Hayes explains. "They have multiple legs — a big set up front, and then a row of six small ones. They're mobile plasma sprayers, like flame-throwers, who shoot plasma like napalm from a nozzle between their eyes; the plasma is ignited by little spark generators dangling in front."

Hayes designed the flying Hopper bugs to appear aerodynamic: "The Hoppers have translucent wings that fold up and fit inside their carapace. They're greenish-blue, with a metallic reflective surface that gives them a futuristic, aerospace feel."

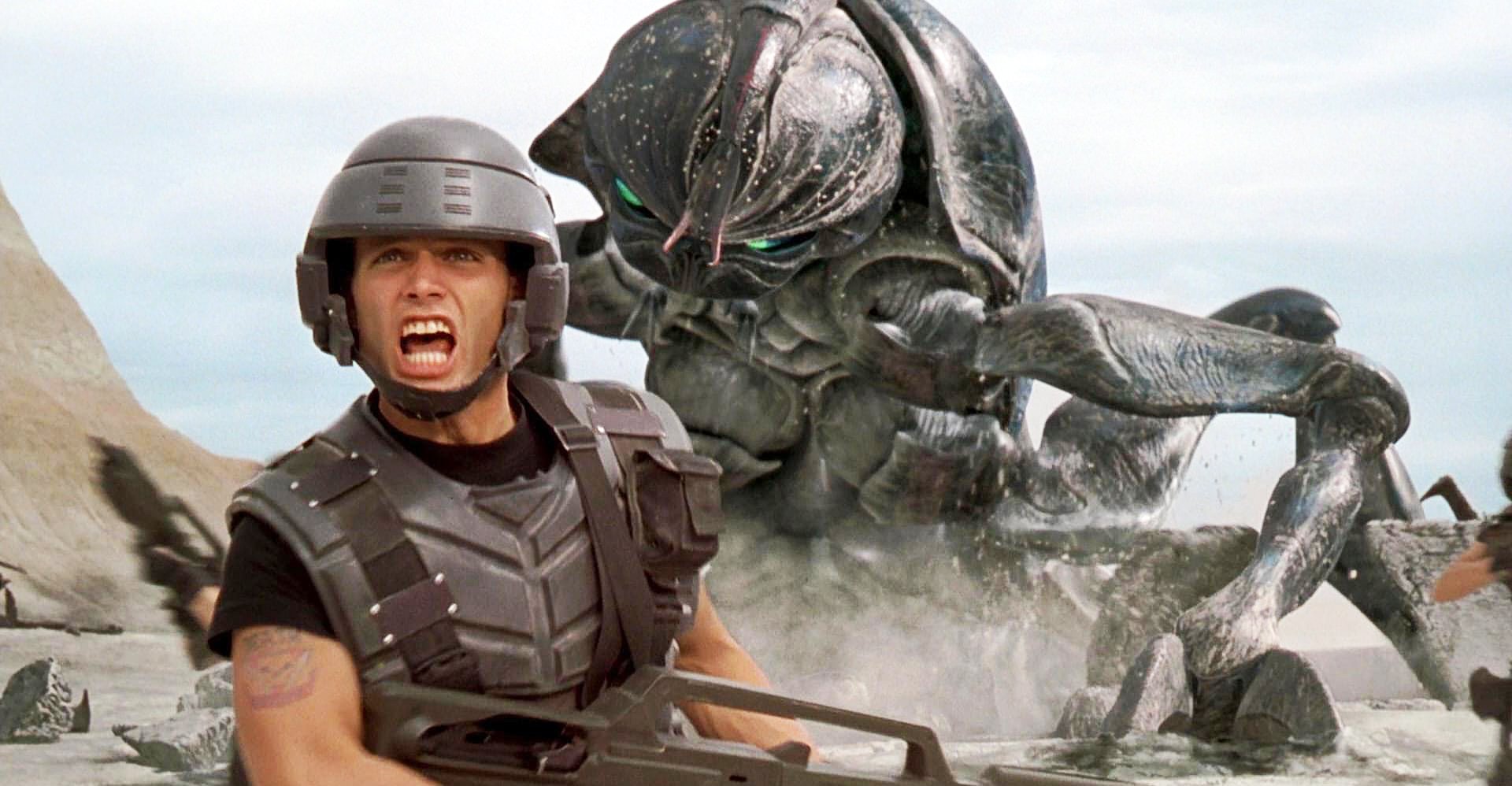

The most ubiquitous of the deadly insects are the preying mantis-like Warrior bugs, which swarm in thousand-unit hordes, gleefully munching on troopers with their massive jaws. "The Warriors were modeled on those big rhinoceros or elephant beetles, which have huge chopping jaws," Hayes explains. "We gave them two attack claws up front to help them draw people into their jaws. To make them look really mean, we gave them graphic splash patterns reminiscent of other predatory animals or insects. The Warriors have yellow-orange stripes like wasps and tigers, and a red strip on top of their heads and jaws so you'll hopefully understand which end's up. We also avoided big round soft shapes; everything is pointed. If one stepped on your toe by accident, it would hurt."

"Their feet even terminate in little ice picks!" Tippett adds. "Ironically, the Warriors were also called the Arachnids, but they bear little resemblance to anything that looks like an arachnid, which by definition has eight legs. Craig made sure they only had four, because we had so many Warriors to deal with; keeping the number of their legs down would give us a bit of an advantage. Making them walk was the hard part. [For the battle sequences on the planet's surface], we were dealing with a heavily textured landscape, so the footfall patterns, the shifting of weight and all of the physical attributes had to constantly be worked on and adjusted. With every step, they had to either go up, around or over a rock."

Nevertheless, the Warriors are impressively fast-moving critters who manage to convey a genuine sense of mass. "There's a balance one is compelled to find," Tippett states. "We wanted a quick, lethal quality, while at the same time making it feel as if each Warrior bug weighed between 1,500 to 1,800 pounds."

Once Hayes designed the alien bugs on paper, Tippett Studio's modelers built scale maquettes of each beast, which were then digitized using a homegrown 3-D scanner. After the bugs' coordinates were input into Silicon Graphics computers, the models were refined in Softimage and then set up with kinematic chains for the animators. They also created high-res models to be used in the final rendering of the images in Renderman. While most of the animation and rendering was done on SGI platforms, much of the painting and compositing was executed on Macintosh machines.

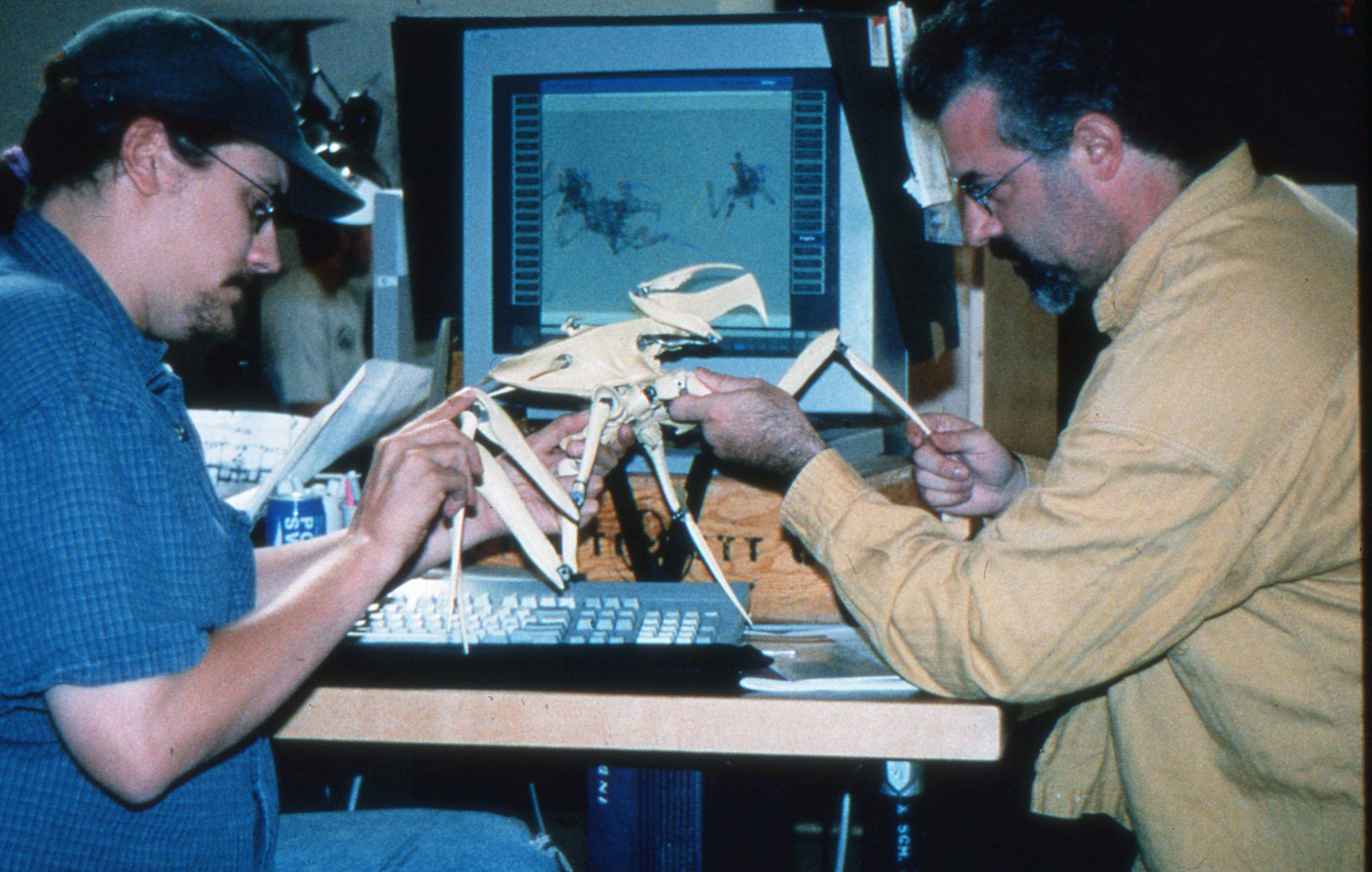

While most of the space insects, including the Tanker, Plasma and Hopper bugs, were computer-animated using keyboards and mouse-clicks, about 30 percent of the Warriors were animated using the Direct Input Device (DID) that Craig Hayes originally developed for Jurassic Park (AC Dec. 1993). The DID enabled Tippett's stop-motion animators to translate their artistry into the computer realm by moving a conventional ball-and-socket animation armature, essentially a machined metal dinosaur skeleton, a frame at a time. But instead of photographing the puppet (as in the conventional stop-motion animation of say, King Kong) sensors on the armature's joints fed information directly into a computer, where the movements of a wireframe dinosaur on a monitor exactly duplicated those of the real-world DID armature. Earlier this year, Hayes received a technical Academy Award for the creation of the DID.

For Troopers, Hayes modified and refined the DID system to make it more user-friendly, and created new armatures to represent the four-legged Warriors. "We mostly made mechanical improvements," Hayes says. "We did everything we didn't have time to do on Jurassic Park. We built extra armatures, so if anybody's puppet broke, we could swap in a new one and repair the old one. We changed the positions of the encoding devices and sensors, and we streamlined the system and improved the speed of its response quite a bit; everything's much faster. There's only a quarter-second delay from the time the animator moves the DID armature to the point when you can see the result on a monitor. There were three animators using the DID, and they could do pretty tight performances. We put a lot of effort into getting most of the bug parts on the DID armature, though some secondary animation had to be done to add the various smaller attack claws. It usually took a couple of days to animate a shot."

To create the Warriors, the DID animators used the system primarily to animate the bugs' keyframe positions. For example, an animator would pose each leg in its beginning, middle and end position, and the computer would fill the gaps in between. Hayes also devised a variation of the system for real-time puppeteering. This technique, more closely related to motion capture than puppet animation, enabled Tippett Studio to quickly generate shots of the bugs leaping or snapping their jaws — recalling the digital rod-puppet method Boss Film used to create its CG alien creature in Species. "The animators manipulated the DID puppet in real time," Tippett says. "Depending on the complexity of the shot, sometimes two or three people would puppeteer them."

Since their work was instantly reviewable and each performance could be saved, the DID animation could be continuously refined as long as time and money permitted. Tippett's animators could critique quick-shaded versions of their shots, then go back and redo parts of the performance.

In shots with multiple creatures, the animators still used a single DID armature to build up layers of animation. "We'd do one performance and use that as reference," Hayes states. "Then our DID software allowed us to play back the pre-recorded performance while the animator animated the new one."

For the larger "crowd scenes," which featured no less than 30 and upwards of 1,200 Warriors, Tippett's crew used procedural animation to generate the swarming hordes. "We created bug walk cycles which we could run over the terrain and rocks," Tippett explains. "We graphically tried to make them appear to be doing the different kinds of things that warrior ants do, so we offset the cycles and determined interesting flows and paths so they almost look like a river of living stuff."

Foremost among Troopers' most ambitious and difficult images is a shot that begins inside the doomed Fourth Brigade Compound on Planet P, where the troopers' rescue effort ends in despair when they find their comrades massacred. Suddenly, a sergeant screams "Bugs!" and the camera travels with the troopers as they race to take their battle stations along the compound walls. The camera then booms up and over the wall and peers down to reveal over 1,000 bugs attacking. "That was the very first shot we did, and the most horrific," Tippett sighs. "The wind was blowing hard on location, and the boom arm was really long, so when it reached the end of its move, it was bouncing. We have a very good match-move department, but that procedure alone took weeks. Then we had to generate close to 1,000 bugs, mostly Warriors and some Tankers. A normal action shot would last maybe five seconds, but this shot needed to run a bit longer so you could figure out what the hell you were looking at. It probably ran 10 seconds because of the level of abstraction, and it took months to put together."

Forget the angst of animating that many bugs, even using procedural techniques: once the animation was finished, this highly detailed shot then had to be rendered. "I think we had some really bad days where it took something like 60 hours to render a frame," Tippett admits. That means that this 10-second shot — which, at 24fps, ran 240 frames — took several months to render. "Once we started getting into it, the management of our resources became extremely critical. We had to put a great deal of effort into finding time-, labor- and render-efficient ways of generating the bugs that ultimately got those horrible 60-hour-per-frame renders down to reasonable 25-to 30-hour renders."

To worsen matters, the Planet P compound sequence occurs in broad daylight, which caused further complications in making the bugs look totally photorealistic. "It's a difficult trick to get the lighting to look right," Tippett agrees. "That's where most computer graphics stuff falls apart. Julie Newdoll, our technical director, was in charge of all the computer graphics lighting. Computer graphics creatures often get overlit in daylight situations, which makes them look a bit flat. There was a great deal of controversy as to how we should go about lighting these things in an efficient manner, and it took a while to get the hang of it. I've really got to hand it to Craig and his art department. They built these things and maintained the integrity of form and surface and color. They were very careful to give the surface qualities of the bugs lots of texture, highlight and sheen. They also made them bright enough to have nice shadows but good detail, which allowed them to feel believable in daylight. They certainly went through a design metamorphosis, but by the time we started putting out finals, I was quite shocked; I couldn't have been more pleased."

Tippett credits Amalgamated Dynamics, Inc. (ADI) for fashioning the full-scale mechanical bugs that thrashed the troopers in close-ups, as well as the dozens of dead bugs that peppered the alien landscapes. Additionally, his animators received tremendous support from editor Mark Goldblatt and his team. "It's difficult for an editor to put effects sequences together, because there's nothing in hem!" Tippett explains. "There are close to 200 shots in which there was literally nothing going on before we got to them. It's an organizational nightmare fitting all of this together and trying to imagine how long each shot should last."

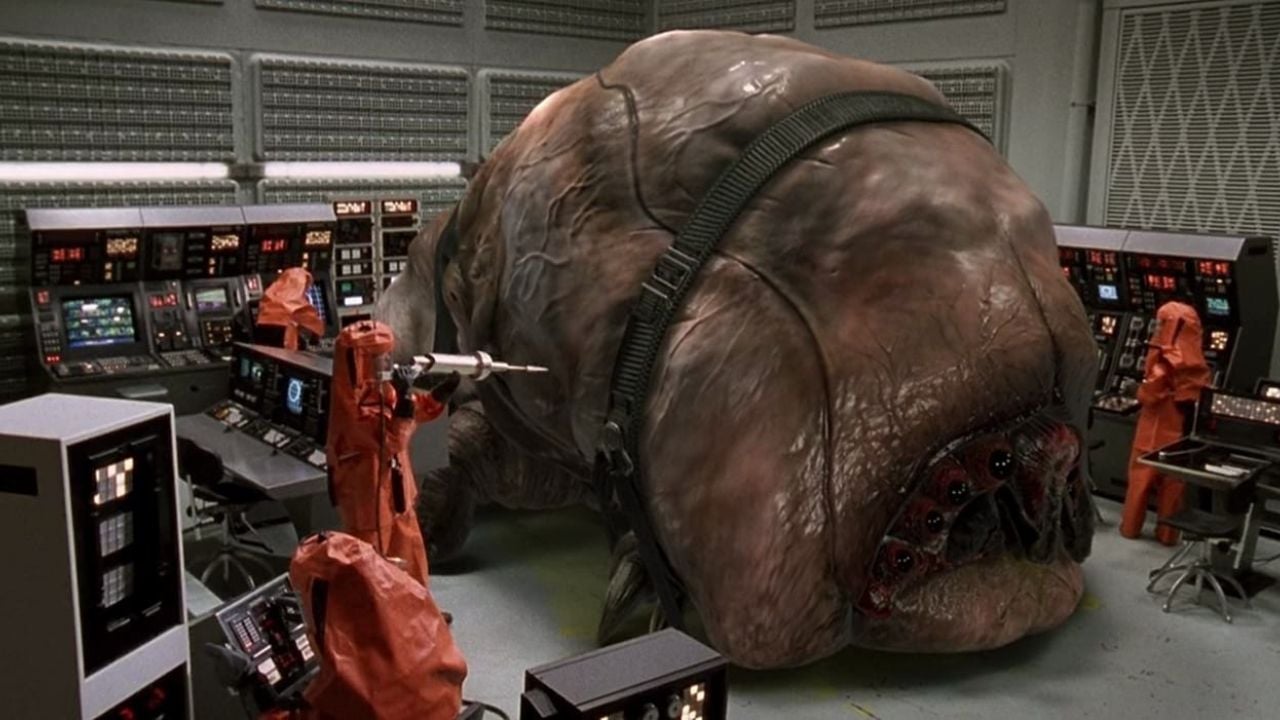

While the battle sequences were roughly accurate to the director's original storyboards, events conspired to prevent the Troopers crew from moving from various locations to the set. Thus, the final sequence, in which our heroes confront the dreaded Brain Bug, required a great deal of improvisation. "The Brain Bug is a pulpy, horrible creature that Paul always thought of as a Godking, Cthulhu-type thing," Tippett laughs, referring to H.P. Lovecraft's demon god. "He does the nasty job of sucking people's brains out, so there are some human sacrifices happening."

"Paul wanted it to look like a queen termite," adds designer Hayes. "He's into biology, so the Brain Bug looks a bit like a pus sack with flesh-colored, undulating sides that resemble a big intestine. Then there are the Chariot Bugs, the Brain Bug's entourage, which are 4-foot-long, cockroach-like things that band together to form a moving carpet which supports him. They're like comic relief."

There was nothing amusing about animating the nasty bug leader, however. "He's a very complicated character," Tippett states. "While all of the other bugs had conventional exoskeletons, the pulpy nature of the Brain Bug necessitated a very complicated flow of shapes. We had some pretty close shots, which took a great deal of time." Despite co-helming nearly 250 shots for Troopers over the past three years, Tippett has yet to conquer his fear of insects: "It's interesting how the world is divided between people who are either terrified by insects or terrified by reptiles. I never was subject to the fear of reptiles, but insects always gave me the creeps. Making this film was no catharsis."

You'll find a complete story on Jost Vacano, ASC, BVK’s cinematography here and the film’s starship effects here.